Implementation of a pharmacist-led transitional pharmaceutical care programme: Process evaluation of Medication Actions to Reduce hospital admissions through a collaboration between Community and Hospital pharmacists (MARCH)

Funding information

This work was supported by the The Royal Dutch Pharmacists Association (Koninklijke Nederlandse Maatschappij ter bevordering der Pharmacie, KNMP)

Abstract

What is known and objective

The recently conducted Medication Actions to Reduce hospital admissions through a collaboration between Community and Hospital pharmacists (MARCH) transitional care programme, which aimed to test the effectiveness of a transitional care programme on the occurrence of ADEs post-discharge, did not show a significant effect. To clarify whether this non-significant effect was due to poor implementation or due to ineffectiveness of the intervention as such, a process evaluation was conducted. The aim of the study was to gain more insight into the implementation fidelity of MARCH.

Methods

A mixed methods design and the modified Conceptual Framework for Implementation Fidelity was used. For evaluation, the implementation fidelity and moderating factors of four key MARCH intervention components (teach-back, the pharmaceutical discharge letter, the post-discharge home-visit and the transitional medication review) were assessed. Quantitative data were collected during and after the intervention. Qualitative data were collected using semi-structured interviews with MARCH healthcare professionals (community pharmacists, clinical pharmacists, pharmacy assistants and pharmaceutical consultants) and analysed using thematic analysis.

Results and Discussion

Not all key intervention components were implemented as intended. Teach-back was not always performed. Moreover, 63% of the pharmaceutical discharge letters, 35% of the post-discharge home-visits and 44% of the transitional medication reviews were not conducted within their planned time frames. Training sessions, structured manuals and protocols with detailed descriptions facilitated implementation. Intervention complexity, time constraints and the multidisciplinary coordination were identified as barriers for the implementation.

What is new and Conclusion

Overall, the implementation fidelity was considered to be moderate. Not all key intervention components were carried out as planned. Therefore, the non-significant results of the MARCH programme on ADEs may at least partly be explained by poor implementation of the programme. To successfully implement transitional care programmes, healthcare professionals require full integration of these programmes in the standard work-flow including IT improvements as well as compensation for the time investment.

1 WHAT IS KNOWN AND OBJECTIVE

Approximately 21% of hospital readmissions are due to Adverse Drug Events (ADEs) and a median of 69% of these ADEs are potentially preventable.1 These ADEs are often the result of changes in medication regimens during hospitalization. Patients transitioning from one healthcare setting to another are susceptible to ADEs due to either provision of unclear patient information regarding medication changes,2, 3 fragmented communication between different healthcare professionals (HCPs)4 or shorter hospital stays, resulting in an increased risk of post-discharge ADEs.5-7

To improve transitional care, several preventive measures consisting of medication reconciliation and clinical medication reviews (CMRs) have been implemented.8 However, these interventions failed to reduce the number of potentially preventable medication-related (re-)admissions, possibly because they were applied in a single setting, rather than in both the hospital and the primary care setting.8-12

Several studies have shown that interventions initiated in the hospital and continued following discharge appeared to have better outcomes in improving continuity of care and reducing the number of preventable ADEs.13-16 However, other studies showed limited effect on ADEs,17, 18 including the recently conducted Medication Actions to Reduce hospital admissions through a collaboration between Community and Hospital pharmacists (MARCH) study.19 This study was carried out in both the hospital and the primary care setting and aimed to investigate the effects of a transitional care programme on the occurrence of ADEs post-discharge (Box 1).

BOX 1. Methodology of the Medication Actions to Reduce hospital admissions through a collaboration of Community and Hospital pharmacists (MARCH) study

The MARCH study was designed as a prospective, before-after study in two hospitals in the Netherlands: a general teaching hospital (OLVG) and a university hospital (Amsterdam UMC, location VUmc). The before measurement of the study was conducted from August 2018 to May 2019, and the after measurement from May 2019 to December 2019. The results have been published elsewhere.19 In short, 369 patients aged 18 years and older using five or more chronic medications, having at least one adjustment in their chronic medication at their discharge from the cardiology, surgery or internal medicine departments and were living in the service area of the participating 49 community pharmacies, were included. The MARCH Programme consisted of four main elements on top of usual care: (1) teach-back at discharge to check patient understanding of medication changes, (2) a pharmaceutical discharge letter23 to inform the community pharmacist among others on medication changes, (3) a home-visit to the patient to discuss medication use and experience, concerns and beliefs regarding medication, and (4) a transitional clinical medication review (tCMR) to discuss Medication-Related Problems (MRPs, i.e. events or circumstances involving medication treatment that actually or potentially interfere with the patient experiencing an optimum outcome of medical care24) identified during the home-visit. Recommendations to solve MRPs were made and implemented in collaboration with the ward physician or the general practitioner. Patients in the control setting received usual care. The primary outcome was the proportion of patients who reported at least one Adverse Drug Event (ADE, i.e. injury resulting from medication use, including physical harm, mental harm or loss of function24) 4 weeks post-discharge.

To interpret the non-significant effect, it is important to understand how MARCH was implemented and performed, and which factors may have affected the study outcomes. Therefore, a process evaluation is necessary to assess whether the MARCH programme itself was ineffective or whether a low quality of the implementation affected the study outcomes.20, 21 One way to do this, is through the assessment of implementation fidelity by using the modified version of the Conceptual Framework of Implementation Fidelity (CFIF).22 Implementation fidelity refers to “the degree to which interventions are implemented as intended by the developers.”21 Framework elements include adherence (content, frequency, duration and coverage of the MARCH programme) and potential moderators (intervention complexity, facilitation strategies, quality of delivery, participant responsiveness, and context).22 Implementation fidelity is considered to be high, when the intervention is consistently delivered according to protocol and a high level of implementation fidelity is achieved for all adherence components. This study aimed to gain insight into the implementation fidelity of the MARCH programme using the CFIF.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design

A mixed methods study was used to guide data collection and analysis. The modified version of the CFIF22 was used to evaluate the implementation fidelity of the MARCH programme.

2.1.1 Conceptual framework for implementation fidelity

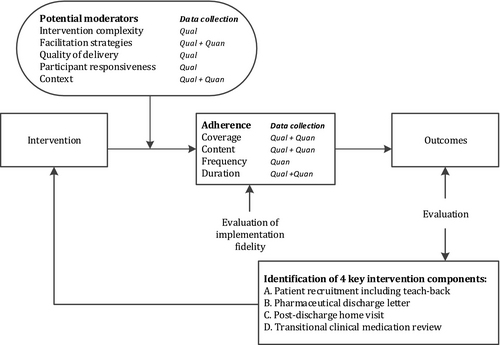

Figure 1 shows the interrelatedness between adherence to the MARCH intervention and moderating factors that may have influenced or affected adherence to the MARCH programme. Adherence to the intervention is the main element of the CFIF and includes the following components: coverage (the degree to which patients that should have received the intervention actually did so), content (the degree to which all essential components of the intervention are implemented), frequency (the degree to which elements of the intervention are delivered) and duration (the degree to how often the intervention elements are delivered). Potential moderating factors include intervention complexity (to which degree the complexity of the intervention is a substantial barrier to its adoption), facilitation strategies (the degree to which strategies, such as training, manuals and guidelines, are delivered), quality of delivery (the manner in which the intervention was delivered in a way appropriate to achieving what was intended), participant responsiveness (to what extent participants receiving (i.e. patients) and participants delivering (i.e. pharmacists and hospital pharmacy personnel) the intervention were committed to the intervention)21 and context (the extent to which factors at political, economic, organizational, and work group levels affected the implementation).22

2.2 Participants

To determine the implementation fidelity, quantitative data of all patients that received the MARCH programme were included. Patients who had not received the full MARCH programme were excluded from the assessment of MRPs (Appendices 3 and 4). Within 3 months after the follow-up of the MARCH programme was finished, all participating MARCH patients were asked to complete a patient survey. Semi-structured interviews with HCPs that had carried out a key element of the MARCH programme were conducted from April 2020 to July 2020.

2.3 Data collection

For the evaluation of the implementation fidelity of the MARCH programme, four key intervention components were identified by the researchers: A. Patient recruitment including teach-back B. Pharmaceutical discharge letter, C. Post-discharge home-visit and D. Transitional clinical medication review. Table 1 presents an overview of specific research questions per key intervention component (A–D) that were assessed for each of the adherence and moderating measures, using the following quantitative and qualitative data sources (indicated by numerals I–VII).

| Key intervention elements | Description of the intervention and by whom carried out | Data sources for the evaluation of adherence components and moderating factors. | Specific research questions of adherence components (Appendix 1) | Specific research questions of moderating factors (Appendix 2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Patient recruitment including teach-back |

|

Quantitative sources:

Qualitative sources:

|

Coverage

Content

Frequency

Duration

|

Intervention complexity

Facilitation strategies

Participant responsiveness

Context

|

|

By whom: hospital pharmacy personnel, that is pharmacy technician in the university hospital or pharmaceutical consultant in the general teaching hospital*. *Pharmaceutical consultants are pharmacy technicians with an additional 3-year bachelor degree, who are specifically trained in pharmacotherapy and communication with patients. |

||||

| B. Pharmaceutical discharge letter |

|

Quantitative sources:

Qualitative sources:

|

Content

Frequency

Duration

|

Intervention complexity

Facilitation strategies

Quality of delivery

Participant responsiveness

Context

|

| By whom: clinical pharmacist composed the pharmaceutical discharge letter and sent it to the community pharmacist. | ||||

| C. Post-discharge home-visit |

|

Quantitative sources:

Qualitative sources:

|

Content

Frequency

Duration

|

Intervention complexity

Facilitation strategies

Quality of delivery

Participant responsiveness

Context

|

| By whom: patient's own community pharmacist or the hospital's outpatient pharmacist in case the community pharmacist was unavailable | ||||

| D. Transitional clinical medication review |

|

Quantitative sources:

Qualitative sources:

|

Content:

Frequency

Duration

|

Intervention complexity

Facilitation strategies

Quality of delivery

Participant responsiveness

Context

|

| By whom: community pharmacists and clinical pharmacist |

2.3.1 Quantitative data sources

- Data on selection, inclusion, drop-out, the logistics, process of the implementation, the flow of patients and data on identified MRPs and recommendations documented by the researcher during the tCMR.

- Gathered during the MARCH programme.

- Data on when the letter was sent out, data on identified or possible MRPs.

- Gathered during the MARCH programme.

- Data on time investment in minutes per home-visit, data on identified MRPs and recommendations.

- Gathered during the MARCH programme.

- Data on reason for participation, and experiences and satisfaction with the different components of the intervention.

- The survey contained a few open-ended questions and several closed-ended questions rated on a 6-point Likert scale (“fully agree,” “agree,” “neutral,” “disagree,” “fully disagree,” “I do not know”). For some statements, the option of “does not apply” was also given.

- Gathered after the follow-up period of the MARCH programme.

2.3.2 Qualitative data sources

- Experiences, implementation and feasibility of the following topics were explored as follows: the eligibility of included patients, the pharmaceutical discharge letter, the home-visit, tCMR, intervention materials, the overall intervention in daily practice, and advantages and disadvantages of the intervention.

- Interviews were conducted until no new themes emerged from three consecutive interviews.

For each of the adherence measures, specific research questions per key intervention component (A–D) were subjectively rated to assess the implementation fidelity. Two researchers independently (SE, EU) assessed this in a qualitative manner by rating the extent to which the different aspects of the intervention were carried out as planned (low, moderate and high). “Low” was defined as almost none of the intervention elements were performed as planned or in case of quantitative data a percentage lower than 50% was found, “moderate” was defined if some elements were carried out as planned or in case of quantitative data a percentage between 50% and 75% was found, and “high” was defined as almost all elements were carried out as planned or in case of quantitative data a percentage higher than 75% was found. The ratings were discussed until consensus was reached. A third researcher (JH) was involved if consensus was not reached.

2.4 Data analysis

Quantitative data were analysed using SPSS statistics for windows version 26.0.0.1 (IBM Corporation). Categorical variables were reported as percentages. Continuous variables were reported as mean with standard deviation (SD) and median with interquartile range (IQR). Qualitative data were analysed using Atlas.ti software for windows version 8 (Scientific Software Development GMBH). Semi-structured interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were analysed using the thematic theory analysis according to Braun & Clark.25 Two independent researchers (SE and AA) coded the transcripts based on the interview topic list. Subsequently, the coded transcripts were arranged to broader themes. Differences were discussed until consensus was reached. A third researcher (JH) was involved if consensus was not reached.

2.5 Ethics approval

The study is conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (version 64, October 2013). The study was approved by the accredited Medical Ethics Committee (METC) of AmsterdamUMC, location VUmc.

3 RESULTS

An overview of the evaluation of adherence and identified moderating factors are described below. More detailed research questions, data sources, outcomes and rating of the researchers are presented in Appendices 1 and 2.

3.1 Adherence to the four intervention components

3.1.1 Coverage

Due to time and financial restraints and the complexity of implementing the MARCH programme in the university hospital, the pre-calculated sample size of 195 patients was not reached. Of the 389 patients that were eligible to participate, 174 patients participated. Two hundred and fifteen patients did not participate due to logistic reasons (n = 89, e.g. patient had already left the hospital or forgotten to ask the patient for participation) or declined participation (n = 126).

3.1.2 Content

The content of three of the four key intervention components were found to be implemented with moderate level of fidelity. Patient recruitment including teach-back was rated as “moderate” due to deviation from the study protocol in the university hospital, where sometimes medication reconciliation was conducted after discharge and where patient recruitment was not carried out by hospital pharmacy personnel. Instead, the pharmacist–researchers carried out the selection and recruitment. The home-visits were not always performed at the patient's home or by the patient's own community pharmacist. Several pharmacists also indicated not to fill out the home-visit protocol during the home-visit, but afterwards. Also, not all received protocols were filled out completely: 37% were partly filled out and 4.7% were not filled out at all. The tCMR often took place in one-on-one meetings between the clinical and community pharmacist instead of in a panel of community pharmacists. Therefore, the desired interaction between several pharmacists who would complement and learn from each other was sometimes missing. The identification of MRP in patients by means of the MARCH programme was delivered as planned (Appendices 3 and 4). On average, 3.9 MRPs (SD 2.02) were identified per patient. For four of the 120 intervention patients that received the full programme, no MRP was identified. Recommendations were made by the pharmacists and were subsequently discussed with the physicians. However, for some recommendations, no follow-up information on the actual implementation of the recommendation was available, due to non-response from either pharmacist or physician. Although most included patients seemed eligible, clinical and community pharmacists indicated that some patients seemed less eligible for the intervention, because of the lack of MRPs.

3.1.3 Frequency and duration

None of the key intervention components were fully implemented with a high level of fidelity (Table 2). In total, 127 patients (73.0%) received the full transitional pharmaceutical care programme. However, during the semi-structured interviews with the hospital pharmacy personnel, it appeared that only three of six (50%) implemented teach-back as intended. Also, 32 of the 56 patients (57%) that filled out the patient survey reported that they were asked to restate the most important adjustments in their medication regimen, indicating that not all patients had received teach-back. Therefore, teach-back implementation was rated as “low.” Both the home-visit and the tCMR often took place after the set time frame. During the home-visit, 96 patients (55.2%) were visited by their own pharmacist and 31 patients (17.8%) by the hospital's outpatient pharmacist. In total, 81 tCMR meetings were conducted.

| Components |

Patients N=174 |

Working days after discharge | Performed within set time framea | Average duration | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(%) | rating | median (IQR) | rating | N(%) | rating | minutes (range) | |

| Teach-back | N/Ab | Low | N/Ab | N/Ab | N/Ab | N/Ab | 7.5 (0–10)c |

| Pharmaceutical discharge letter | 173 (99.4) | High | 1 (0–2) | High | 109 (63.0) | Moderate | 30 (20–120)c |

| Home-visit | 127 (73.0) | Moderate | 6 (4–11) | Moderate | 45 (35.4) | Low | 47 (15–105) |

| tCMR | 134 (77.0) | High | 11 (8–17) | Moderate | 59 (44.0) | Low | 19 (7.5 – 45)d |

| Full transitional care programme | 127 (73.0) | Moderate | – | – | – | – | – |

- a The pharmaceutical discharge letter, home-visit and tCMR ought to be performed within 1, 5 and 10 working days after discharge, respectively.

- b Could not be assessed; quantified data on these matters was unreliable.

- c Estimated duration, derived from qualitative data (interviews).

- d Time per discussed patient.

- e Ratings on the amount of patients in which the component was performed, working days within it was performed and if it was performed within the set time frame, respectively.

3.2 Moderating factors

3.2.1 Complexity

During the interviews with the hospital pharmacy personnel, forgetting, uncooperative or impatient patients, lack of experience, not knowing how to conduct teach-back and lack of time, were mentioned as reasons for not implementing teach-back as intended. Lack of time was reported most often as medication reconciliation itself could take up to 20 min. Clinical pharmacists mentioned that composing the pharmaceutical discharge letter using solely the electronic patient record (EPR) was quite complex, as not all information was always available. Community pharmacists reported that conduction of the home-visit, filling out the home-visit protocol and performing the tCMR was very time-consuming. Both clinical and community pharmacists indicated that it was difficult to properly conduct the intervention in daily practice within the set timeframes. Additionally, organizational barriers were identified by clinical pharmacists, namely arranging the tCMR at a time when everyone was available.

3.2.2 Facilitation strategies

Patient recruitment including teach-back were facilitated by training sessions by the researchers, a study manual and incentives, such as festive celebrations when a milestone was reached.

To facilitate the home-visit and tCMR, all community and clinical pharmacists were invited prior to the study for a two-hour training session, which consisted of ten medication-related readmission cases, study information and instructions how to properly and consistently carry out the MARCH programme. The pharmacists received a detailed manual with information on study procedures and intervention materials. Those who had not attended the training also received a URL to a recorded training session. The training was accredited for pharmacists and they also received financial compensation for every CMR. Patients did not receive financial compensation, nor did clinical pharmacists.

During the interviews, most pharmacists rated the training session as a useful preparation. However, some also indicated that non-innovative as they already had a lot of experience with tCMRs. Three interviewed pharmacists indicated that they had not attended the training and used the structured manual as preparation instead. They considered this was clear and sufficient to enable proper participation in the study.

3.2.3 Quality of delivery and participant responsiveness

All community and clinical pharmacists were positive towards the pharmaceutical discharge letter, home-visit and tCMR, and these were considered to be very valuable to identify MRPs. Community pharmacists indicated that the discharge letter saved them much time to prepare the home-visit. Furthermore, community pharmacists indicated that the home-visit was more valuable than a telephone call, as they experienced that it gave them more information on a patient. Cooperation during the tCMR was considered to be good and complementary knowledge was helpful. However, for the tCMR, most community and clinical pharmacists indicated that one-on-one phone calls would be more efficient. Hospital pharmacy personnel indicated that they saw the MARCH programme as added value for patients when it comes to improving adherence. However, not all hospital pharmacy personnel knew what the transitional care programme exactly comprised or why certain wards were chosen to include patients. Additionally, some thought that teach-back was irrelevant, as they already asked patients if they had understood the medication information provided and if they had any further questions. Thirty-one patients (55.4%) that filled out the patient survey reported that they found it useful to participate, and 47 (83.9%) were satisfied with the received care during the intervention (score of 70 or higher out of 100).

3.2.4 Context

Several differences between the general teaching hospital and university hospital were observed. The hospitals differed in usual pharmaceutical care, which was more extensive in the general teaching hospital. In the teaching hospital, teach-back had already been implemented, and participating pharmacists in its urban area were more familiar with home-visits due to previous studies. Moreover, the population of patients seemed to differ in the university hospital as younger and higher educated patients using less medication were admitted.

Both community and clinical pharmacists indicated that they had many other work priorities during the transitional care programme. They stated that to conduct the transitional care programme properly, more employees should be deployed and therefore appropriate financial reimbursement should become available to successfully implement the MARCH programme in daily practice.

4 DISCUSSION

This study examined the implementation fidelity of the MARCH study; a pharmacist-led transitional care intervention programme to enhance medication safety after hospital discharge. Understanding how the MARCH programme was delivered and determining critical moderating factors clarifies whether the non-significant effect of the programme was due to poor implementation or due to ineffectiveness of the programme as such and is necessary to implement and improve transitional care programmes. Several complex pharmacy-led transitional care studies have been conducted.13-16, 26-31 However, only a few have evaluated its implementation fidelity.30, 31 Overall, findings of this study revealed four moderating factors including (1) complexity, (2) contextual factors, (3) facilitators and (4) quality of delivery and participant responsiveness, which might have influenced implementation fidelity of the programme components.

The transitional care programme was considered complex because of its multiple extensive and time-sensitive intervention components. Inability to incorporate all intervention components into existing practices, especially without additional financial compensation, was considered to be the most important contextual factor. These factors contributed to the low level of fidelity for the proportion of patients that received the home-visit and were discussed during the tCMR within the established time frame (frequency). Providing financial incentives may enhance pharmacists to align their priorities with organizational support, such as more personnel,30, 32, 33 which would enable them to incorporate transitional care programmes in their existing working routines.30, 31 Similar studies on transitional care programmes reported implementation difficulties as the result of inabilities to standardize transitional care programmes due to heterogeneity of patients32 and the need to tailor the programme to the patient's needs,31, 32 which may have contributed to intensive time-investments. Difficulties in recruitment of patients resulted in a low implementation fidelity for the included eligible patients (coverage). More than half of the patients were excluded due to logistical reasons (e.g. patient was already discharged, forgotten to ask, patient was unavailable) leading to lower inclusion rates. Inclusion of patients who may not need or want the intervention, or were not feasible for the intervention may also have led to a low programme effect.34 Improvements in the EPR may help with the identification of patients at high risk of problems after discharge. Facilitators, such as the training sessions, structured manual with detailed intervention description and the home-visit protocol, made the implementation more uniform and therefore positively influenced the delivery of the intervention.31, 32 These factors resulted in a high implementation fidelity for the pharmaceutical discharge letter (content and frequency) and the tCMRs (frequency). The pharmaceutical discharge letter was sent within a median of one day for 99% of the patients and 77% of the patients were discussed during the tCMR. The quality of delivery and participant responsiveness was generally good. Most pharmacists considered the pharmaceutical discharge letter, home-visit and tCMR to be valuable for identification of MRPs shortly after hospital discharge. However, not all pharmacy technicians and pharmaceutical consultants knew what the transitional care programme exactly comprised nor did they see the relevance of performing teach-back. This resulted in a low level of fidelity for the degree to which recruitment including teach-back was performed (content and frequency). Apparently, pharmacy technicians and consultants should be trained in a more intensive way. Moreover, although many patients who filled out the patient survey were also positive on the extra services from the pharmacists, not all found it useful to participate in the study. This may have consequently influenced participant responsiveness negatively, thereby promoting non-adherence to the programme.

4.1 Key implications and recommendations

The MARCH programme identified a large number of MRPs (n = 468). Many (n = 342, 73.1%) were solved by acceptance of the recommendations from the pharmacists during one of the intervention elements and multiple pharmacists reported to have identified MRPs that prevented possible calamities from occurring, suggesting that the transitional care programme may prevent hospital re-admissions. However, no significant effect on ADEs was observed. This could be explained by the study's moderate and low implementation fidelity of the components of the MARCH programme. Opportunities for future research include enhancing the transitional care programme and determining what patients would benefit the most from the programme. Particular refinements would include exploring how to best incorporate transitional care programmes into daily practice to improve the efficiency and feasibility of the programme. Additionally, increasing information technology in the EPR, such as creating a template for the pharmaceutical discharge letter and improving secure electronic messaging systems between hospitals and primary care, may enhance selection of patients at risk and improve communication between clinical pharmacists and community pharmacists. Finally, to focus pharmacists’ priorities on transitional care (i.e. the performance of time-consuming home-visits and tCMRs), adequate financial compensation can be used to increase programme fidelity.

4.2 Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the implementation fidelity of a transitional care programme in the Netherlands. The qualitative methods used in this study provided more detailed information on the transitional care intervention fidelity. Limitations may have influenced the evaluation. First, the researchers who carried out the intervention were also involved in the process evaluation, and a subjective rating was used to measure implementation fidelity. However, this was carried out independently by two researchers, and differences were discussed with the research team. Second, the interviews and the patient survey were conducted after the trial. Therefore, participants may have experienced recall bias when reflecting on the trial. Third, recordings of teach-back, the home-visit and tCMRs might have provided more insight into the way these elements were performed and how patients perceived the intervention. Finally, the intervention was executed in a large setting. Pharmacies throughout the entire Amsterdam area participated in the study. Therefore, many different HCPs were included in the study, who were all inexperienced at performing the complete programme and who often conducted the programme in only a few of their patients. Performing the programme within a smaller setting, with fewer HCPs who would more often conduct and therefore learn from the programme, could possibly lead to a higher implementation fidelity. No clinical redesign assessment35 was performed before the start of the MARCH study, which is needed to assess the existing systems of the hospitals and to identify likely barriers and possible solutions in advance. However, a similar transitional care programme, performed previously in two Dutch hospitals by the research team showed promising effects on ADEs and was a complex intervention as well.16, 36 Barriers and facilitators were assessed for transitional care from both the patient perspective and the HCP perspective.37, 38 Therefore, for the general teaching hospital, the existing system and barriers could be assessed in advance throughout the aforementioned study. Although a similar intervention was successfully applied in another study, it might have been better to carefully assess the specific barriers and facilitators of both participating institutions and consider a clinical redesign of our study. Moreover, since roughly one-third of eligible patients declined to participate selection bias cannot be ruled out. Nonetheless, the current research design provides insight into the implementation fidelity and its possible effect on the MARCH study's effect outcomes.

5 WHAT IS NEW AND CONCLUSION

Overall, the implementation fidelity was moderate for most key intervention components of the transitional care intervention. This means that these components were not fully carried out as planned. The lack of effect on ADEs in the intervention group might be partially due to poor implementation as opposed to ineffectiveness of the intervention itself. Moderators, such as intervention complexity, lack of time and organizational difficulties, might also have negatively influenced the implementation fidelity. Successfully implementing a transitional care intervention programme in daily practice for the involved HCPs requires full integration in the standard work-flow including IT improvements as well as financial compensation for the time investment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to all the participating patients. We would also like to thank the clinical pharmacists and hospital pharmacy personnel from the two participating hospitals, and all the community pharmacists who participated in this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

ETHICAL APPROVAL STATEMENT

The study is conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (version 64, October 2013). The study was approved by the accredited Medical Ethics Committee (METC) of AmsterdamUMC, location VUmc.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

Informed consent was obtained from all the participating patients. Patients participating in the MARCH program were only included if they had provided written informed consent. All participating MARCH patients were subsequently invited to fill out the patient survey after the follow-up of the MARCH program was finished.

PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE MATERIAL FROM OTHER SOURCES

No material from other sources was used in this manuscript.

APPENDIX 1: Research questions, data sources and outcomes per key intervention component for the evaluation of adherence

| Key intervention components | Research questions | Data sourcea | Outcomes | Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coverage – the extent of which the intended proportion the target group participated in the intervention | ||||

| In general | What proportion of selected patients were invited to participate? | I | In total 174 patients (89.2%) were included. This was not enough to reach the pre-calculated sample size of 195 patients. The intended number of at least 95 patients per hospital was achieved in the general teaching hospital (n = 106). In the university hospital only 68 patients were included | Low |

| What proportion of patients were not eligible and why? | I | In total, 1400 patients from two hospitals were screened for participation in the intervention arm. Of these patients 1011 patients (72.8%) were not eligible: 644 patients (46%) did not meet the inclusion criteria; <5 chronic medications at discharge (n = 407) and no change in medication regimen (n = 237). And 367 patients (26.2%) were excluded due to transfer to another institution (n = 240), length of hospital stay <24 h (n = 4), mental constraints (n = 31), language barrier (n = 51), life expectancy <6 months (n = 25) or other reasons such as patient was too sick to participate (n = 16) | N/A | |

| What proportion of patients declined and why? What proportion of eligible patients participated? How was drop-out? And why? | I | Of the 389 patients (27.8%) that were eligible, 215 (55.3%) were excluded; 89 (22.9%) due to logistical reasons (e.g. patient was already discharged, forgotten to ask, patient was unavailable) and 126 (32.4%) declined to participate. Reasons to decline participation were no interest, too ill, or study was not considered useful. The remaining 174 patients were willing to participate. During follow-up 17 patients (9.8%) discontinued participation and 29 patients (16.7%) were lost to follow-up due to unavailability of the patient (n = 20), health issues (n = 2), readmission (n = 5) and death (n = 2) | N/A | |

| How was the eligibility of participants perceived by pharmacists? | VI, VII | Most community and outpatient pharmacists stated that they considered the minimum of five chronic medication and at least one medication change the most important selection criteria. However, several pharmacists indicated that these criteria should not be limited to just chronic medications and that non-chronic medications, such as opiates, should also be included. Furthermore, despite the exclusion criterion of patients being at a palliative stage, a few pharmacists indicated to have performed a home-visit with a terminally ill patient. This was considered to be inappropriate. Clinical pharmacists indicated that they were unsure if the right study population was used. They also indicated that inclusion should not be limited by medication and that the type and number of medications might be reconsidered. Some opted to screen for certain triggers in the electronic patient record (EPR), such as difficulties mentioned by the doctors or nurses. Ideally nurses and doctors or someone involved in the patient's discharge procedure would be a part of the selection procedure, since they have spoken to the patient during admission and can detect patients that are at risk. Another clinical pharmacist mentioned that the selection criteria were very strict, which was good on the one hand, as there always was something to intervene on. On the other hand it was thought that the intervention would be suitable for other patients as well, which is why was opted for slightly broader criteria, such as risk departments. Two clinical pharmacists also stated that oncology patients should not have been included, since they are already under constant care, monitored closely and visit the hospital frequently, one clinical pharmacist said this was also true for haematology patients. Geriatrics was also mentioned as a department in which patients could be included. Another said that patients might be selected based on their illness or comorbidities. It was also mentioned that patients whose follow-up would take place in another hospital should be excluded, since the clinical pharmacist found it difficult to perform the intervention in those patients | N/A | |

| What proportion of patients filled out the patient survey? | I | Of the 120 patients invited, 56 patients (46.7%) filled out the patient survey. For 64 patients data was lost to follow-up due to non-response (n = 52), study discontinuation (n = 5), health issues (n = 1) or death (n = 6) | N/A | |

| Content - the extent to which each of the intervention components were implemented as planned | ||||

|

A. Patient recruitment including teach-back B. Pharmaceutical discharge letter C. Post-discharge home-visit D. Transitional clinical medication review |

To what extent were the different components of the patient recruitment including teach-back delivered as planned? | I, V | Patient recruitment including teach-back was not fully carried out by hospital pharmacy personnel as was planned by the researchers. In the general teaching hospital the pharmaceutical consultants performed recruitment including teach-back, as was planned. In the university hospital the recruitment was carried out differently, namely by the researchers who were temporarily part of the hospital pharmacy where medication reconciliation including the newly introduced teach-back method was conducted. Medication reconciliation including teach-back generally took place face-to-face at the day of discharge. However, at the university hospital medication reconciliation including teach-back was sometimes conducted after discharge, by means of a telephone call The manner to which teach-back was conducted as planned could not be assessed, since it was not feasible to monitor by the researchers. Three out of six of the interviewed hospital pharmacy personnel stated that they did not conduct teach-back as intended by the researchers | Moderate |

| To what extent were the different components of the pharmaceutical discharge letter delivered as planned? | I, II, VI, VII | The pharmaceutical discharge letter was drafted by pharmacy students or researcher (SE) and subsequently assessed and approved by the clinical pharmacist. This letter was sent to the community pharmacist by the clinical pharmacist in the general teaching hospital and by the researcher (SE) at the university hospital. The letter contained all discharge medication in the general teaching hospital and only changed medication with the full medication list attached in the university hospital. Occasional shortcomings mentioned by a few interviewed community and outpatient pharmacists were that some letters were incomplete (e.g. missing laboratory values) or incorrect (e.g. wrong indication). Some clinical pharmacists indicated that information may have been missed, because there were no healthcare professionals, such as physicians or nurses, involved that had actually spoken to the patient and might have known some difficulties that patients were experiencing | High | |

| To what extent were the different components of the post-discharge home-visit delivered as planned? | I, III, VI | The home-visit was performed by patient's own community pharmacist. If unavailable, the hospital's outpatient pharmacist performed the intervention. All interviewed pharmacists indicated that they used the structured home-visit protocol, which consisted of three parts: assessment of patient's wellbeing and points of attention (1), Medication use (2) and experiences, concerns and beliefs regarding medication (3). However, several pharmacists mentioned they filled out the protocol after the home-visit rather than during and not all protocols were fully filled out. 58.3% (n = 74) were completely filled out and 4.7% (n = 6)were not filled out at all and two protocols (1.4%) were not sent to the researchers. Most protocols were received by the clinical pharmacist in advance of the tCMR. Not all pharmacists conducted the home-visit at the patient's home. Two pharmacists said to have conducted the review at the pharmacy at request of the patient | Moderate | |

| To what extent were the different components of the tCMR delivered as planned? | I, VI, VII | For the tCMR community pharmacists were invited to also evaluate cases of fellow pharmacists. However, several one-on-one meetings were conducted, rather than meetings with multiple pharmacists as it was not feasible. When multiple pharmacists did attend, there was little participation in other community pharmacists’ cases | Moderate | |

| To what extent was the identification of MRPs in patients delivered? | I, II, III | For 116 patients (96.7%) one or more MRPs were identified and recommendations were made to solve the MRPs (n=468, mean 3.9 MRPS per patient; Appendices 3 and 4). For four patients no MRP was identified | N/A | |

| Frequency and duration – the extent to which the intervention components were implemented as often and for as long as planned | ||||

|

In general A. Patient recruitment B. Pharmaceutical discharge letter C. Post-discharge home-visit D. Transitional clinical medication review |

How many transitional pharmaceutical care programmes were fully performed? | I, II | 127 patients (73.0%) received the full transitional pharmaceutical care programme. However, 7 patients received the tCMR after the primary outcome was measured. Reasons for an incomplete transitional pharmaceutical care programme were due to unavailability of the patient (n = 5), study discontinuation (n = 25), readmission (n = 9), death (n = 1) or unavailability of the community pharmacist (e.g. holiday, lack of time, discontinued participation) (n = 7). | Moderate |

| How often did patient fill out the questionnaire on ADEs 4-weeks post-discharge and how many reported at least one ADE? | I, II | During the transitional care programme, 128 patients (73.6%) filled out the questionnaire on ADEs V weeks post-discharge and 78 patients (60.9%) reported at least one ADE. 101 (68.2%) of these patients received the full transitional programme, of which 59 patients (58.4%) reported at least one ADE four weeks post-discharge. | N/A | |

| How many times was medication reconciliation including teach-back performed? | I, V, IV | The degree to which teach-back was conducted could not be properly assessed. During the intervention none of the pharmacy personnel reported that they did not conduct teach-back at discharge. Therefore, it was assumed that 174 patients received medication reconciliation including teach-back. However, during the interviews it became clear that not every one of their team had carried out teach-back as planned by the developers. In addition, 54 of the 56 patients that filled out the evaluation survey stated that they received medication reconciliation and 32 (57%) filled out that they had received teach-back (8 patients were neutral, four did not know and four were missing) | Low | |

| How many pharmaceutical discharge letters were sent? | I, II | For 173 patients (99.4%) the pharmaceutical discharge letters were sent | High | |

| How many working days were there between discharge and the pharmaceutical discharge letter? | I, II | The pharmaceutical discharge letter was sent out within a median of one working day after discharge (IQR of 0–2), where the letter was sent within a median of one working day (IQR 0–2) after discharge in the general teaching hospital and within a median of two working days (IQR 1–2.75) in the university hospital | High | |

| What proportion of discharge letters was sent within one working day? | I, II | For 109 patients (63%) the pharmaceutical discharge letter was sent within one working day after discharge | Moderate | |

| How many post-discharge home-visits were performed? What was their average duration? | I, III, VI | For 127 patients (73.0%) home-visits were conducted, where 96 patients (75.6%) were visited by their own pharmacist and 31 patients (24.4%) by the hospital's outpatient pharmacist. Averagely the home-visit lasted 47 min (range 15 min – 1 h 45 min) | Moderate | |

| Within how many working days was the home-visit conducted? | I, III | The home-visit took place within a median of six working days after discharge (IQR 4–11). Patients of the general teaching hospital were visited with a median of 6 working days (IQR 4–11) and patients of the university hospital with a median of seven working days (IQR 6–12) | Moderate | |

| What proportion received the home-visit within five working days? | I, III | For 45 patients (35.4%) the home-visit took place within five working days | Low | |

| How many tCMRs were performed? What was their average duration? | I | There were 81 transmural cMR meetings conducted, in which 134 patients (77%) were discussed, with an mean duration of 19 min (range 7.5–45 min) per discussed patient | High | |

| Within how many working days was the tCMR conducted | I | The transmural cMR took place within a median of 11.5 working days (IQR 8–17), with a median of 10 working days (IQR 7–16) in the general teaching hospital and 12 working days (10–18.5) in the university hospital | Moderate | |

| For what proportion was the tCMR performed within ten working days? | I | For 59 patients (44%) the transitional clinical medication review was performed within 10 working days | Low | |

| What was the estimated duration to select and recruit a patient? | V | Pharmacy personnel indicated that the screening of a patient took on average 5 min. Some said the time spent to select a patient was negligible, since they already looked up the same information to prepare themselves for medication reconciliation at discharge. Others reported that it took them averagely 5 more minutes to search for additional inclusion criteria. The recruitment took approximately 10 min on average (min. 5 to max. 15 min) | N/A | |

| What was the estimated duration to perform teach-back? | V | According to pharmacy personnel it averagely took 7,5 (range 0–10) min to perform teach-back | N/A | |

| What was the estimated duration to compose the pharmaceutical discharge letter? | VII | Clinical pharmacists said it took 20–120 min to compose the pharmaceutical discharge letter, depending on the amount of medication and the complexity of the hospitalization | N/A | |

- a I researcher data; II pharmaceutical discharge letter; III home-visit protocol; IV patients survey; V interview pharmacy technicians and pharmaceutical consultants; VI interview community and outpatient pharmacists; VII interview clinical pharmacists.

APPENDIX 2: Research questions, data sources and outcomes per key intervention component for the evaluation of moderating factors

| Key intervention components | Research questions | Data source | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention complexity – the complexity of the intervention | |||

|

A. Patient recruitment B. Pharmaceutical discharge letter C. Post-discharge home-visit D. Transitional clinical medication review |

How complex were the different components of the patients recruitment and teach-back? | V | Hospital pharmacy personnel indicated that due to forgetting, impatient patients, experience and lack of time teach-back was not always implemented as intended. Especially lack of time seemed to be crucial. They often mentioned that medication reconciliation with patients with a lot of medication changes could take up to 20 min. They stated that if those patients would be asked to restate all of the medication changes, then the conversation would last too long. Some, implied that they did not see teach-back to be of added value. A few said they had not heard of teach-back before. Others were under the impression that they were performing teach-back by asking the patient if they understood the medication information or if there were any questions about their medication. They stated that they did not know they had to ask the patient to restate the medication-related information on medication changes |

| How complex were the different components of the pharmaceutical discharge letter? | VII | Clinical pharmacists said that it was difficult to compose the pharmaceutical discharge letter by means of solely the EPR, because they had no contact with the patient. Therefore, they preferred the pharmaceutical letter be drafted in collaboration with or by someone who has contact with the patient, such as a nurse or physician. In addition, they stated composing the letter was a very intensive and time-consuming, especially within a timeframe of one day, and they thought it would be useful if a template was created | |

| How complex were the different components of the post-discharge home-visit? | VI | The majority of community pharmacists evaluated the protocol description as clear and informative. Although, some pharmacists also indicated that the protocol was very extensive and time-consuming to fill out. Other difficulties to fill out the protocol properly were: not enough space to write, hard to find a question during a conversation, difficult to use when patients are using a dispensing system or when caretakers are managing the patient's medication and illogical order of topics. For patients that experienced no clear problems or difficulties, pharmacists indicated that it was difficult to properly use the intervention materials, since for these patients providing information and advice seemed not necessary. Additionally, they experienced time pressure, as the home-visit was expected to be performed within five working days. If they had other priorities in the pharmacy, then this timeframe could not always be met | |

| How complex were the different components of the tCMR? | VI, VII | During the study, both community and clinical pharmacists indicated difficulties mostly due to lack of time combined with the timeframe to conduct the tCMR. Several community pharmacists said it was impossible for them to join other cases during the tCMR and preferred just to discuss the outcomes of their own patient only. Clinical pharmacists experienced organisational difficulties when it came to arranging the tCMR. Gathering community pharmacist for the meetings cost a lot of time, since not everyone was available at the proposed times | |

| Facilitation strategies – strategies to support implementation and how these strategies were perceived by staff involved in the project | |||

|

A. Patient recruitment B. Pharmaceutical discharge letter C. Post-discharge home-visit D. Transitional clinical medication review |

What were strategies to support the implementation of patient recruitment? | I |

Training session: A few weeks in advance of the start of the study participating hospital pharmacy personnel in the hospitals were trained by the pharmacist-researches (SE, EU) to properly conduct the patient selection, teach-back communication and patient recruitment. However, not everyone had attended the training session Study manual: at the start of the study hospital pharmacy personnel received an overview of how to properly select patients and carry out the recruitment including teach-back Intensive monitoring: researchers had extensive contact with the hospital pharmacy personnel and monitored progress Incentives: festive treats were given whenever a certain percentage of patients was included |

| How were these strategies perceived by the pharmacy technicians and consultants? | I, V |

In general, the training was perceived as clear and also portrayed a clear expectation of the additional tasks for the MARCH study. However, it was indicated that more structured information on the predefined patient selection criteria would have been helpful along with a demonstration or practice session Initially the manual was considered to be too ambiguous and the selection criteria were unclear, specifically the ambiguity of which pharmacies were participating and which medications were considered as chronic. Therefore, it was difficult to recruit the right patients in the beginning. However, adjustments to the manual were made and this was considered to be much more conclusive and clear. Extensive support by the researchers was considered to be very helpful. They stated that it was nice that the researcher would take on the tasks, whenever they experienced lack of time |

|

| What were strategies to support the implementation of the pharmaceutical discharge letter? | I | Several elements where implemented into the EPR. To lessen the workload of the clinical pharmacist, the researchers or students drafted a first version of the pharmaceutical letter. Basic information and all medication changes were written up by means of the EPR. Clinical pharmacists checked the information and made adjustments | |

| How were these strategies perceived by the clinical pharmacists? | VII | Extensive support by the researchers regarding the preparation of the pharmaceutical discharge letter was considered to be very helpful, since the clinical pharmacist did not have the time to fill out information that could be easily found in the EPR such as patient characteristics | |

| What were strategies to support the implementation of the post-discharge home-visit and tCMR? | I |

Two hour training session: To prepare participating clinical and community pharmacists for the programme, a training was developed. Pharmacists of 49 community pharmacies and a clinical pharmacist from both hospitals followed the training session prior to the study. This training was conducted by pharmacist-researchers (SE, EU, JH, FK) and consisted of ten medication-related readmission cases, study information and instructions how to carry out the programme. Not all community and clinical pharmacists attended the training session. Those who did not attend received a recorded training session prior to the study Study manual: At the start of the study all pharmacists received a detailed manual with information on study procedures and intervention materials Intensive monitoring: The researcher had extensive contact with pharmacists in order to monitor progress and meeting deadlines and to provide feedback if necessary Incentives: The training was accredited for pharmacists and they also received a financial compensation for every conducted home-visit in accordance with the compensation for medication reviews. Hospital pharmacy personnel received festive treats whenever a certain percentage of patients were included. Patients did not receive incentives |

|

| How were these strategies perceived by the community pharmacists? | VI | In general the training was considered useful. Especially the medication-related cases were considered to be of added value. Some thought it was nice to practice with the study materials of the MARCH study. Others did not think it was necessary. Some pharmacists also indicated that the training was not challenging enough as most pharmacists have a lot of experience with performing CMRs. Despite it not being considered as innovative, it was thought to be needed to get everyone on the same page both in expectation and way of conducting the different intervention elements. The manual was considered to be a clear and sufficient tool to prepare for the MARCH study tasks, especially by those that had not attended the training session. Some used it to refresh their memories, others did not use it all. Altogether, everyone shared the opinion that having the manual was useful for the purpose of having some background information on the study. Contact with the researchers was considered to be good, although some pharmacists said that they rather received a message on their phone or a friendly reminder in their private email as opposed to being reached at work (on their work phone or email). Pharmacists indicated that the financial compensation was not enough as they had to put a lot of time into performing the transitional care. It was considered to be fine in a study setting, but would not be feasible in a usual care setting | |

| Quality of delivery – the quality of delivering the intervention components | |||

|

A. Patient recruitment B. Pharmaceutical discharge letter C. Post-discharge home-visit D. Transitional clinical medication review |

How was the quality of the pharmaceutical discharge letter evaluated by pharmacists? | VI, VII | Most pharmacists considered the pharmaceutical discharge letter to be clear and overall quite complete. Community pharmacists mentioned that it saved them a lot of time as they did not need to make calls in order to receive some of the information noted in the letter. It was also considered to be a good preparation for the home-visit. Clinical pharmacists also saw opportunities to implement the letter in usual care, as some medication-related errors could be found during the composition of the letter. Although, they indicated that other healthcare professionals, such as nurses, physicians or pharmacy technicians, should be involved in drafting the letter. Thereby, they said the letter needed to be properly included into the EPR |

| How was the quality of the home-visit evaluated by pharmacists? | VI | Pharmacists were of the opinion that the home-visit could give them a good idea of the medication use of patients. However, the use of the home-visit protocol during the conversation did not make sense to all the pharmacists, because it felt impersonal. Most found it necessary to have such protocols during CMRs, either for preparation, as a reminder to ask certain questions or to make sure all pharmacists were conducting the interview in a similar way. Most pharmacists indicated that a home-visit was more valuable than a telephone conversation, since they could more easily identify medication-related problems at the patient's home. Additionally, they indicated that it allowed them to develop a better relationship and trust with their patients. In addition, pharmacists were of the opinion that they were the right person to conduct the home-visits. A few mentioned that this may be assigned to pharmacy technicians as well | |

| How was the quality of the tCMR evaluated by pharmacists? | VI, VII | The tCMR was considered to be of use as it allowed both parties to discuss and solve medication uncertainties. Both community and clinical pharmacists indicated that cooperation was considered to be good and complementary knowledge was helpful. Community pharmacist also indicated that the tCMR allowed for more accessible contact with hospital HCPs. Both pharmacists indicated that a PowerPoint presentation and videoconference was not necessary. Especially when it came to information regarding the patient, since both parties had already collected that information themselves. Therefore, they indicated that a tCMR by telephone would suffice. Also, one-on-one meetings were considered to make more sense than the initial plan to conduct the meetings with a panel of community pharmacists | |

| How was the quality of the different components of the transitional care programme evaluated by participants? | IV | In general, 82.1% of the 56 patients that filled out the patient survey indicated they did not ran into any problems or questions regarding their medication when back at home. During the home-visit 73.3% of the patients indicated that all matters important for them with regards to their medications were discussed accordingly. The conversation with the community pharmacist was perceived as useful by 67.9% of the patients. The home-visit by the community pharmacist had met the patient's expectation in 59.0% of the cases, where approximately 20% of the patients answered ‘does not apply’ and 12.5% ‘neutral’, indicating that they had no clear expectation | |

| Participant responsiveness – participant engagement, satisfactions and perception of outcomes and relevance to the intervention | |||

| In general | How engaged and satisfied were pharmacy technicians and consultants with the intervention? | V | Hospital pharmacy personnel indicated that they saw the transitional care programme as added value to patients when it comes to improving adherence. However, not everyone knew what the transitional care programme included or why certain wards were chosen to include patients. They mentioned that the inclusion rates could have been higher if the pulmonology and neurology department had been included and the oncology department was excluded. Finally, not all members thought teach-back was relevant, as they already estimated the extent to which patients understood the medication reconciliation. Altogether, most members stated that they enjoyed participation, although time restraints remained an issue |

| How engaged and satisfied were pharmacists with the intervention? | VI, VII | All interviewed pharmacists considered the pharmaceutical discharge letter and its elements valuable and useful. All interviewed community pharmacists commented they found the discharge letter highly informative and thought it should be implemented in usual care. Pharmacists considered the home-visit to be very useful, since it provided them with background information on the patient's hospital admission and medication use in their daily life. The tCMR was considered to be of use as it allowed both parties to discuss and solve medication uncertainties. Both community and clinical pharmacists stated that cooperation was considered to be good and complementary knowledge was helpful. Community pharmacist also indicated that the tCMR allowed for more accessible contact with hospital HCPs | |

| How engaged and satisfied were patients with the intervention? | IV | Of the 56 patients that filled out the patient survey, 31 (55.4%) found it useful to participate, 17 (30%) felt neutral, 3 (5.4%) did not find it useful (no reasons given), 1 (1.1%) did not recall and four (4.4%) answers were missing. On a scale of 0–100, with 0 being very unsatisfied and 100 being very satisfied with the transitional care programme, 47 (98%) patients reported their satisfactory to be 70 or higher (2 missings). Reasons given for a satisfactory lower than 70 were: programme was deemed unnecessary due to no problems, home-visit should have taken place sooner, not satisfied with medication changes, mainly unsatisfied with the hospitals discharge procedure and therefore also unsatisfied with the intervention, home-visit did not take place or being unsatisfied with communication | |

| Context– the extent to which factors may have affected the implementation | |||

| In general | How did organizational activities affect the implementation? | I | Organizational differences between the general teaching and university hospital were observed. First of all, usual care was more extensive for the general teaching hospital, making it easier to implement the intervention compared to the university hospital. Second, more complex patients from throughout the country were hospitalized at the university hospital, whereas more local patients were admitted to the general teaching hospital. Therefore, many patients could not be included in the university hospital as their community pharmacy was outside the urban region who were not participating in this study. Third, participating community pharmacists in the urban region of the general teaching hospital had more experience in performing home-visits, due to previously conducted studies in the hospital. Finally, in the university hospital the pharmaceutical discharge letter and the tCMR were often performed by two different clinical pharmacists, as opposed to the general hospital, where the clinical pharmacist-researcher performed both components |

| How did economical activities affect the implementation? | VI, VII | All interviewed healthcare professionals stated that performing the transitional care programme is a very time-consuming matter. They stated that they had other work-related priorities, which meant that the transitional care programme had to be done in their spare time. They indicated that to conduct it properly, financial compensation for the performance of time-consuming home-visits and tCMR should be given or more employees should be deployed | |

| How did group activities affect the implementation? | VII | Clinical pharmacists mentioned it was not always easy to set up joined tCMRs since they sometimes did not get a response upon e-mails, experienced no-shows or interference on the line during videoconference | |

- I researcher data; II pharmaceutical discharge letter; III home-visit protocol; IV patients survey; V interview pharmacy technicians and pharmaceutical consultants; VI interview community and outpatient pharmacists; VII interview clinical pharmacists.

APPENDIX 3: Frequencies and percentages of identified MRPs and the corresponding intervention component according to the D.O.C.U.M.E.N.T. classification39 for intervention participants (N = 120)a

| DOCUMENT MRP type |

Discharge letter N (%) |

Home-visit N (%) |

tCMR N (%) |

Total N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug selection | 6 (1.3) | 75 (16.0) | 28 (6.0) | 109 (23.3) |

| D1 – Duplication | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| D2 – Drug interaction | – | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| D3 – Wrong drug | 1 | 4 | 3 | 8 |

| D4 – Incorrect strength | 2 | 5 | 1 | 8 |

| D5 – Inappropriate dosage form | – | 9 | 2 | 11 |

| D6 – Contraindication apparent | – | 3 | – | 3 |

| D7 – No indication apparent | 1 | 48 | 19 | 68 |

| D0 – Other drug selection problem | 1 | 2 | – | 3 |

| Over or underdose | 1 (0.2) | 31 (6.6) | 11 (2.4) | 43 (9.2) |

| O1 – Prescribed dose too high | 1 | 4 | 6 | 11 |

| O2 – Prescribed dose too low | – | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| O3 – Incorrect/unclear dosing instruction | – | 22 | 2 | 24 |

| O0 – Other dose problem | – | 3 | – | 3 |

| Compliance | 4 (0.9) | 103 (22.0) | 4 (0.9) | 111 (23.7) |

| C1 – Taking too little | 1 | 18 | 2 | 21 |

| C2 – Taking too much | – | 9 | – | 9 |

| C3 – Erratic use of medication | – | 9 | 1 | 10 |

| C4 – Intentional drug misuse | – | – | – | – |

| C5 – Difficulty using dosage form | – | 12 | – | 12 |

| C6 – Not taking medication | – | 19 | 1 | 20 |

| C7 – Continue taking discontinued medication | – | 7 | – | 7 |

| C8 – Drug discrepancy | 3 | 11 | – | 14 |

| C0 – Other compliance problem | – | 18 | – | 18 |

| Un(der)treated indications | 0 | 27 (5.8) | 8 (1.7) | 35 (4.5) |

| U1 – Condition undertreated | – | 9 | 2 | 11 |

| U2 – Condition untreated | – | 13 | 5 | 18 |

| U3 – Preventative therapy required | – | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| U0 – Other undertreated problem | – | – | – | – |

| Monitoring | 0 | 13 (2.8) | 10 (2.1) | 23 (4.9) |

| M1 – Laboratory monitoring | – | 11 | 10 | 21 |

| M2 – Non-laboratory monitoring | – | 2 | – | 2 |

| M0 – Other monitoring problem | – | – | – | – |

| Education or information | 1 (0.2) | 78 (16.7) | 0 | 79 (16.9) |

| E1 – Patient requests drug information | – | 12 | – | 12 |

| E2 – Patient requests disease management | – | 2 | – | 2 |

| E3 – Confusion about therapy or condition | 1 | 58 | – | 59 |

| E4 – Demonstration of device | – | 5 | – | 5 |

| E0 – Other education or information problem | – | 1 | – | 1 |

| Not classifiableb | 0 | 42 (9.0) | 0 | 42 (9.0) |

| Toxicity | 0 | 24 (5.13) | 2 (0.4) | 26 (5.6) |

| T1 – Toxicity caused by dose | – | 2 | – | 2 |

| T2 – Toxicity caused by drug interaction | – | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| T3 – Toxicity evident | – | 19 | 1 | 20 |

| T0 – Other toxicity problem | – | 1 | – | 1 |

| Total | 12 | 393 | 63 | 468 |

- Abbreviation: tCMR, transitional clinical medication review.

- a For patients that received the full transitional care programme before the primary outcome was measured.

- b Clinical interventions that does not belong elsewhere, such as the pharmacists discovered expired, unwanted, or unused medicines at the patient's home, pharmacist discovered insufficient medical supplies (i.e. incontinence pads, catheters, dietary foods for malnutrition)or the pharmacists recognized the load of medicines the patient was using and advised a multi-dose drug dispensing system.

APPENDIX 4: Frequencies and percentages of recommendations to solve MRPs for intervention participants (N = 120)a

| Document recommendation type | Accepted in primary care | Not accepted in primary care | Unknown in primary care | Accepted in secondary care (2J) | Not accepted in secondary care | Unknown in secondary care | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacological recommendations, N (%) | 116 (24.8) | 12 (2.6) | 60 (12.8) | 38 (8.1) | 10 (2.1) | 22 (4.7) | 258 (55.1) |

| Recommendations for medication changea | 67 (14.3) | 8 (1.7) | 55 (11.8) | 26 (5.6) | 10 (2.1) | 22 (4.7) | 188 (40.2) |

| Medication initiation | 8 | 3 | 14 | 2 | – | 3 | 30 |

| Medication cessation | 25 | 4 | 22 | 11 | 5 | 6 | 73 |

| Medication switch | 6 | – | 8 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 24 |

| Dosage regimen change (increase/decrease/frequency) | 24 | – | 10 | 11 | 2 | 8 | 55 |

| Medication formulation change | 4 | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | 6 |

| Recommendations for medication discrepanciesb | 49 (10.5) | 4 (0.9) | 5 (1.1) | 12 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 70 (15.0) |

| Medication initiation | 15 | 3 | 4 | 5 | – | – | 27 |

| Medication cessation | 18 | – | – | 3 | – | – | 21 |

| Medication switch | 3 | 1 | – | – | – | – | 4 |

| Dosage regimen change (increase/decrease/frequency) | 13 | 0 | 1 | 4 | – | – | 18 |

| Non-pharmacological recommendations | 182 (38.9) | 1 (0.2) | 12 (2.6) | 7 (1.5) | 2 (0.4) | 6 (1.3) | 210 (44.9) |

| Education and information | 118 (22.4) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (1.5) | 5 (1.1) | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.9) | 134 (28.6) |

| Education on medication indications and workings | 66 | – | 1 | 2 | – | – | 69 |

| Education on medication adherence | 14 | – | 1 | – | – | – | 14 |

| Education on medication regimen | 6 | – | 1 | 1 | – | 1 | 9 |

| Education on side effects and side effect relieve | 6 | – | 2 | 2 | – | 2 | 12 |

| Recommendation multi-dose system | 18 | – | 2 | – | 1 | 1 | 22 |

| Instruction session | 8 | – | – | – | – | – | 8 |

| Practical problems | 6 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.3) |

| Difficulty opening medication | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | 2 |

| Difficulties swallowing medication | 4 | – | – | – | – | – | 4 |

| Monitoring | 18 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.1) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | 28 (6.0) |

| Laboratory test | 14 | – | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 20 |

| Non-laboratory test | 4 | – | 3 | – | 1 | – | 8 |

| Collection of spare medication | 40 (8.5) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 42 (9.0) |

| Total | 285 (60.9) | 26 (5.6) | 72 (15.4) | 45 (9.6) | 12 (2.6) | 28 (6.0) | 468 |

- a Recommended medication changes to optimize the patient's therapy.

- b Recommended medication changes due to discrepancies between the patient's current medication list and the medication used by the patient.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

No additional data are available.