Clinical outcomes in hypertensive patients treated with a single-pill fixed-dose combination of renin-angiotensin system inhibitor and thiazide diuretic

Funding information

This study is supported by grant from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (grant No. CORPG3F0571, CORPG3G0751, and CMRPG3E1051).

Abstract

Two or more antihypertensive agents are required to achieve blood pressure control for the most hypertensive patients. However, comparison of clinical outcomes between fixed-dose combinations (FDC) and free-equivalent combinations of renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitor and thiazide diuretic is lacking nowadays. Patients who were newly diagnosed with hypertension between July 1st, 2008 and December 31st, 2011 and prescribed with FDC (n = 13 176) or free combinations of RAS inhibitors and thiazide diuretic (n = 4392) were identified from the National Health Insurance Research Database of Taiwan and matched in 3:1 ratio using the propensity score method. The primary end point was major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). The secondary end points were hospitalization of heart failure, new diagnosis of chronic kidney disease, and the initiation of dialysis. Compared with he FDC group was associated with better medication adherence compared with the free combination group. FDC of RAS inhibitor and thiazide diuretic reduced MACE (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.85; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.74-0.97; P = 0.017), hospitalization for heart failure and initiation of dialysis compared with the free combination regimens. The outcome benefits of FDC was mainly driven by reduced cardiovascular and renal events in the patients with proportion of days covered <80%. In this retrospective claims database analysis, compared with the free combination regimens, the use of FDC of RAS inhibitor and thiazide diuretic was associated with improved medication compliance and clinical outcomes in the management of hypertension, particularly in the patients with poor medication adherence.

1 INTRODUCTION

Hypertension has long been recognized as a global public health challenge and the leading preventable risk factor for cardiovascular diseases (CVD).1-3 Clinical studies had demonstrated that adequate blood pressure control substantially reduces end organ damage and improves cardiovascular outcomes.4, 5 Despite enormous advances in medical therapy, the control rates of hypertension worldwide seem to remain low,6 specifically 47% in the United States,7 34% in England, 66% in Canada,8 and 25% in Taiwan.9 This leads to the incentive to explore more effective antihypertensive regimens.

Two or more antihypertensive agents are usually required to achieve desirable blood pressure control for the majority of hypertensive patients.10-12 However, medication nonadherence and lack of persistence have been recognized as critical factors of inadequate blood pressure control.13, 14 Previous study have demonstrated that single-pill fixed-dose combinations (FDC), compared with free-equivalent combinations,15 are more effective in improving medication compliance and therefore may possibly result in the reduction of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and healthcare expenditure.16 Despite the numerous combinations of angihypertensive agents, the outcome data of FDC regimens in hypertenstion treatment is still lacking. The combination of renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitor and thiazide diuretic is a well accepted and increasingly prescribed regimen in Taiwan, particularly in drug-naïve hypertensive patients.17 Given the lack of large-scale randomized controlled trials, we aimed to perform a retrospective claims database analysis to compare the clinical outcomes of FDC vs free combinations of RAS inhibitor and thiazide diuretic in real-world hypertension management.

2 METHODS

2.1 Data source

We used the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) of Taiwan to conduct this retrospective cohort analysis. The National Health Insurance (NHI) program, a state operated, universal health insurance program implemented since 1995, covers 99% of the entire Taiwanese population.18-21 The NHIRD of Taiwan contains inpatient and outpatient registries from all medical facilities contracted with the National Health Insurance Administration and provides patient information on gender, birthday, diagnosis, prescribed medications, and invasive procedures. These data could be identified using the diagnosis and procedure codes of the International Clinical Diseases, the Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). The Bureau of NHI encrypted all personal identifiers before information was released to researchers. Confidentiality was addressed by following the data processing regulations set by the Bureau of NHI. The Institutional Review Board approval was waived.

2.2 Study cohort and design

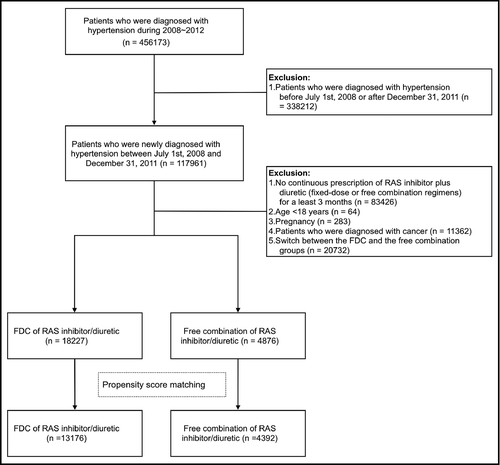

Figure 1 illustrates the flow chart of patient enrollment. Patients with the diagnosis of hypertension (ICD-9-CM: 401.x) between January 2008 and December 2012 were identified from the NHIRD of Taiwan. To ensure all the patients enrolled in this study were newly diagnosed with hypertension, we excluded the patients who were diagnosed with hypertension or prescribed with any antihypertensive drug before July 1st, 2008. We also excluded those who were diagnosed after December 31st, 2011 to ensure that all the patients had a least 1 year of follow-up in the present study. This study aimed to compare the clinical outcomes of FDC vs free combination of RAS inhibitor and thiazide diuretic. The index date was defined as the date of the first prescription of single-pill fixed-dose combination of RAS inhibitor and thiazide diuretic in the FDC group and the concomitant prescription of free components of RAS inhibitor and thiazide diuretic in the free combination group. Considering there were occasional users of the study drugs, we excluded the patients who were not prescribed with the study drugs uninterruptedly for at least 3 months. This 3-month period was chosen because the NHI reimbursement policy of Taiwan allows a maximum length of 3 months for medication refills for chronic illnesses. We also excluded the patients who were aged <18 years, who were diagnosed with pregnancy or cancer, and those with concurrent prescription of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor and angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) or switch between these two classes of drugs during the study period.

Propensity score matching was performed to eliminate the differences in the baseline characteristics of the two study groups. The variables used in the matching process included age, gender, coronary artery disease (including a history of myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG), peripheral artery disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, chronic kidney disease (CKD), Carlson score, and baseline medications (antiplatelet agent, calcium channel blocker [CCB], beta-blocker, other classes of antihypertensive drugs, statins, and oral antidiabetic agents). The FDC group was matched in 3:1 ratio to the free combination group.

2.3 Study end points and follow-up

The primary end point was MACE, including all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction (410-410.9), stroke (430-437), and coronary revascularization (PCI: 36.0-36.03 and 36.05-36.09; CABG: 36.1-36.99 and V45.81). Mortality was identified using death certificate data files of the NHIRD of Taiwan. The secondary end points included hospitalization for heart failure (428.0-428.10), new diagnosis of CKD (585), and the initiation of dialysis. All patients were followed up for at least 1 year or till the occurrence of clinical end points, whichever came first. Medication adherence was assessed using proportion of days covered (PDC), which is defined as the total number of days covered by the study drugs divided by the total number of days of the study period.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were compared using Student's t test, and categorical variables were analyzed by the Chi-square test. Data are presented as means, standard deviations, or percentages. Cox proportional hazard model was used for time to event analysis. Analysis of clinical outcomes was further stratified by medication adherence (PDC ≥80% and PDC <80%). All analyses were conducted using SAS Statistical Software, Version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and R Statistical Software, Version 3.0.1 (the R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A P value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3 RESULTS

Table 1 demonstrates the demographic and baseline characteristics of the two study groups. From July 1st, 2008 to December 31st, 2011, a total of 13 176 hypertensive patients who received FDC and 4392 patients who received free combinations of RAS inhibitors and thiazide diuretics were identified from the NHIRD of Taiwan and matched in 3:1 ratio using the propensity score method. The mean age of the study patients was 58, with 53% of them with male. Approximately 23% of the study patients had diabetes mellitus, 19% had dyslipidemia, 4.4% had CKD, and 10% had previous documented CVD, including coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, and heart failure. The mean Carlson score was 1.5 for both the two groups. No significant difference was observed between the two groups in terms of demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and baseline medications after propensity score matching.

| Before matching | After matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed-dose combination | Free combination | P-value | Fixed-dose combination | Free combination | P-value | |

| (n = 18 227) | (n = 4876) | (n = 13 176) | (n = 4392) | |||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Male, n (%) | 9785 (53.7) | 2633 (54.0) | 0.707 | 6968 (52.9) | 2352 (53.6) | 0.453 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 58.72 (13.42) | 60.01 (14.20) | <0.001 | 58.79 (13.48) | 58.98 (13.80) | 0.420 |

| Age, n (%) | ||||||

| 18-29 | 179 (1.0) | 47 (1.0) | <0.001 | 124 (0.9) | 46 (1.0) | 0.981 |

| 30-39 | 1057 (5.8) | 269 (5.5) | 741 (5.6) | 251 (5.7) | ||

| 40-49 | 3446 (18.9) | 897 (18.4) | 2621 (19.9) | 859 (19.6) | ||

| 50-59 | 5397 (29.6) | 1287 (26.4) | 3727 (28.3) | 1235 (28.1) | ||

| 60-69 | 3939 (21.6) | 1028 (21.1) | 2798 (21.2) | 935 (21.3) | ||

| >69 | 4209 (23.1) | 1348 (27.6) | 3165 (24.0) | 1066 (24.3) | ||

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 4293 (23.6) | 1166 (23.9) | 0.612 | 3040 (23.1) | 1021 (23.2) | 0.828 |

| Dyslipidemia | 3512 (19.3) | 984 (20.2) | 0.159 | 2534 (19.2) | 876 (19.9) | 0.311 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 919 (5.0) | 319 (6.5) | <0.001 | 585 (4.4) | 213 (4.8) | 0.277 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1599 (8.8) | 533 (10.9) | <0.001 | 1056 (8.0) | 383 (8.7) | 0.148 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 244 (1.3) | 78 (1.6) | 0.189 | 185 (1.4) | 64 (1.5) | 0.854 |

| Congestive heart failure | 570 (3.1) | 299 (6.1) | <0.001 | 73 (0.6) | 32 (0.7) | 0.235 |

| Charlson score, mean (SD) | 1.16 (1.56) | 1.28 (1.62) | <0.001 | 1.10 (1.51) | 1.14 (1.53) | 0.201 |

| Charlson score, n (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 9481 (52.0) | 2354 (48.3) | <0.001 | 7042 (53.4) | 2305 (52.5) | 0.563 |

| 1 | 2508 (13.8) | 710 (14.6) | 1752 (13.3) | 590 (13.4) | ||

| 2 | 3087 (16.9) | 838 (17.2) | 2243 (17.0) | 747 (17.0) | ||

| 3+ | 3151 (17.3) | 974 (20.0) | 2139 (16.2) | 750 (17.1) | ||

| Baseline medications, n (%) | ||||||

| Antiplatelet agents | 5350 (29.4) | 1586 (32.5) | <0.001 | 3754 (28.5) | 1308 (29.8) | 0.106 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 10 728 (58.9) | 3072 (63.0) | <0.001 | 8267 (62.7) | 2758 (62.8) | 0.964 |

| Beta-blocker | 6954 (38.2) | 2065 (42.4) | <0.001 | 5217 (39.6) | 1731 (39.4) | 0.845 |

| Other antihypertensive drugs | 887 (4.9) | 351 (7.2) | <0.001 | 373 (2.8) | 114 (2.6) | 0.442 |

| Statins | 3778 (20.7) | 1057 (21.7) | 0.153 | 2671 (20.3) | 922 (21.0) | 0.315 |

| Oral antidiabetic agents | 4827 (26.5) | 1243 (25.5) | 0.168 | 3439 (26.1) | 1100 (25.0) | 0.173 |

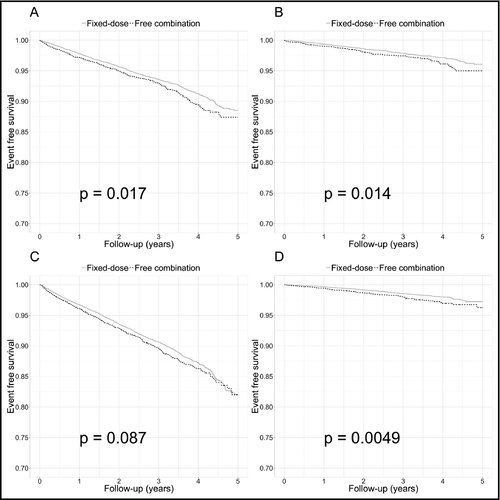

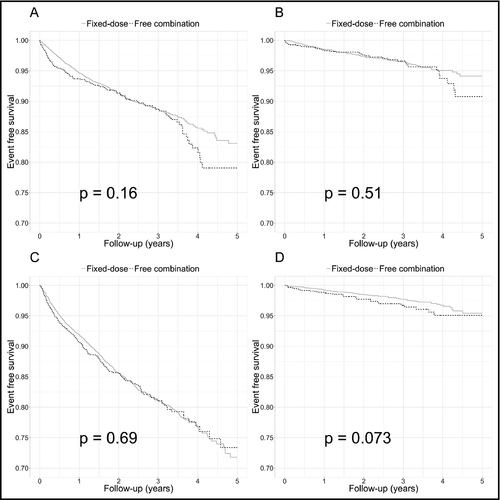

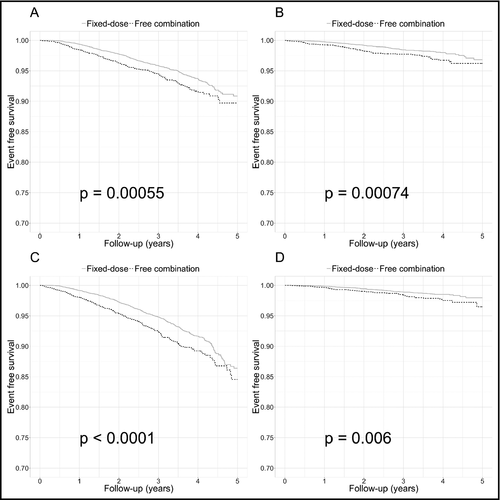

The use of FDC was associated with better medication adherence (PDC 58.01% vs 46.96%; P < 0.001) compared with the free combination group (Table 2). Regarding the clinical outcomes, FDC was associated with a significant reduction in MACE compared with the free combination regimen (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.85; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.74-0.97; P = 0.017; Table 3 and Figure 2). The FDC group also had better outcomes in terms of hospitalization for heart failure (HR 0.76; 95% CI 0.6-0.95; P = 0.015) and initiation of dialysis (HR 0.69, 95% CI 0.53-0.89; P = 0.005). There was no significant difference between the two groups regarding new diagnosis of CKD (HR 0.91; 95% CI 0.81-1.01; P = 0.087). We further stratified the outcome analysis based on PDC (Table S1). In patients with PDC ≥80%, the clinical outcomes did not differ significantly between the two groups (Figure 3). On the other hand, among the patients with PDC <80%, FDC was associated with better survival free from MACE and all the secondary end points (Figure 4).

| Fixed-dose combination | Free combination | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of follow-up (d), mean (SD) | 887.89 (456.09) | 830.22 (462.50) | <0.001 |

| Proportion of days covered (PDC), mean (SD) | 58.01% (33.01%) | 46.96% (36.52%) | <0.001 |

| PDC ≥80%, n (%) | 4670 (35.4) | 1240 (28.2) | <0.001 |

| Outcomes | Group | Event number | Person-year | Incidence rate (per 100 person-year) | Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary end point (MACE) | Free combination | 293 | 10 941.830 | 2.678 | 1 | (Reference) |

| Fixed-dose | 785 | 34 495.321 | 2.276 | 0.85 (0.74-0.97) | 0.017 | |

| Hospitalization for heart failure | Free combination | 108 | 11 258.419 | 0.959 | 1 | (Reference) |

| Fixed-dose | 257 | 35 402.573 | 0.726 | 0.76 (0.6-0.95) | 0.015 | |

| New diagnosis of CKD | Free combination | 407 | 10 751.701 | 3.785 | 1 | (Reference) |

| Fixed-dose | 1164 | 33 971.951 | 3.426 | 0.91 (0.81-1.01) | 0.087 | |

| New initiation of dialysis | Free combination | 80 | 11 343.786 | 0.705 | 1 | (Reference) |

| Fixed-dose | 173 | 35 600.836 | 0.486 | 0.69 (0.53-0.89) | 0.005 |

- CKD, chronic kidney disease; MACE, major adverse cardiac events; RAS, renin-angiotensin system.

4 DISCUSSION

In this retrospective cohort analysis, we used the NHIRD of Taiwan to evaluate the clinical outcomes of fixed-dose and free combinations of RAS inhibitor plus thiazide diuretic. We found that compared with the free combination regimen group, the FDC of RAS inhibitor and thiazide diuretic was associated with better medication adherence and persistence and improved clinical outcomes in the treatment of hypertension. Subgroup analysis showed that the FDC and free combination regimens had comparable outcomes in patients with good medication adherence (PDC ≥80%). In patients with PDC <80%, the FDC of RAS inhibitor and thiazide diuretic was associated with better outcomes compared with the free combination regimens.

Several classes of blood pressure lowering drugs, including diuretics, ACE inhibitors, ARB, CCBs, and beta-blockers, had been proven to be effective in reducing blood pressure and preventing morbidity and mortality of uncontrolled hypertension.22-27 Diuretics enhance the antihypertensive efficacy of multidrug regimens and are more affordable than other antihypertensive agents.28 The benefits of diuretic-based therapy in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and stroke have been established in the earliest randomized clinical trials in the 1960s and in the contemporary studies.25, 29 Among the different classes of diuretics, thiazide diuretics have been regarded as the cornerstone of antihypertensive therapy, especially in the elderly (the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program [SHEP] study)30 and the African-Americans (the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack [ALLHAT] study).25 On the other hand, the RAS is a major therapeutic target in hypertension management, especially for patients with high cardiovascular risk, left ventricular dysfunction, and heart failure.31-35 The Avoiding Cardiovascular Events through Combination Therapy in Patients Living with Systolic Hypertension (ACCOMPLISH) study has revealed that benazepril plus amlodipine decreases the rate of cardiovascluar events compared to benazepril plus hydrochlorothiazide.36 Nevertherless, the combiations of RAS inhibitors and thiazide diuretics are still widely prescribed in contemporary hypertension management. In Taiwan, an increasing number of treatment-naïve patients receive FDC of RAS inhibitor and thiazide diuretic as their first drug for hypertension treatment.36

The single-pill combinations of antihypertensive drugs have been shown to improve patient compliance37-41 and have therefore been recommended by current guidelines in hypertension management.42-45 However, no trial has ever been performed to compare the clinical outcomes of the FDC of RAS inhibitor and thiazide diuretic vs the free combinations of separate drugs. In the present study, we found that FDC regimens was associated with improved medication adherence and persistence compared with the free combination regimens, which is in line with results of the previous studies. We hypothesized that through the improvement in medication compliance, FDC may have beneficial impact on cardiovascular and renal outcomes in patients with hypertension. Furthermore, the benefits of FDC seemed to be driven by the improved outcomes in patients with PDC <80%. Therefore, in the management of hypertension, patients with poor adherence should be identified and clinicians may consider FDC as a reasonable alternative in this particular subgroup to improve medication compliance and long-term prognosis.

4.1 Study limitations

There are severel inherent limitations in this retrospective claims database analysis. The NHIRD of Taiwan collected prescription information and therefore does not contain data on laboratory tests or blood pressure recods. The lack of blood pressure records at baseline and follow-up visits precludes the analysis of the control rate of hypertension in our study cohorts. Despite the use of propensity score matching to balance the difference in the prescriptions of statins and hypoglycemic agents, we could not exclude the potential differences in the levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and glycohemoglobin between the two groups, which have been shown to affect the long-term cardiovascular outcomes in hypertensive patients. Similarly, the lack of creatinine data may confound the secondary end points of new CKD and the initiation of dialysis. Furthemore, the reasons behind the prescription of FDC or free combination regimens was not provided by the NHIRD of Taiwan. The preferences of patients or physicians may also lead to selection bias in our study. Finally, the study cohort was limited to the Taiwanese population and therefore the results of the present study may not be generalized to other popluations.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this retrospective claims database analysis, compared with the free combination regimens, the FDC of RAS inhibitor and thiazide diuretic was associated with improved medication compliance and clinical outcomes in the management of hypertension, particularly in the patients with poor medication adherence.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.