ESG did not immunize stocks during the COVID-19 crisis, but investments in intangible assets did

Abstract

Environmental, social and governance (“ESG”) scores have been widely touted as indicators of share price resilience during the COVID-19 crisis. Contrary to this conventional wisdom, we present robust evidence that once industry affiliation, market-based measures of risk and accounting-based measures of performance, financial position and intangibles investments have been controlled for, ESG offers no such positive explanatory power for returns during the COVID crisis. Specifically, ESG is insignificant in fully specified returns regressions for each of the Q1 2020 COVID market crisis period and for the full COVID year of 2020. By contrast, a measure of the firm's stock of investments in internally generated intangible assets is an economically and statistically significant positive determinant of returns during each of the Q1 market implosion and full 2020 COVID year periods. Our results are robust to alternative measures of returns, as well as for using Refinitiv, Refinitiv II and MSCI data to capture ESG performance. We conclude that ESG did not immunize stocks during the COVID-19 crisis, but those investments in intangible assets did.

1 INTRODUCTION

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic led to a steep and rapid decline in global capital markets during the first quarter of 2020.1 From its peak on February 19, 2020, the S&P 500 index had lost 34% by March 23, before recovering slightly by the end of the first quarter. In the wake of this pandemic-induced carnage, there were widespread claims that firms’ environmental, social and governance (“ESG”) performance served as a shield in sparing socially responsible firms the more devastating value destruction experienced by their lesser ESG-performing peers.2 “Responsible investment” fund managers and ESG data purveyors alike have been perpetuating the reputation of ESG as a resilience factor, with Morningstar even referring to ESG as an “equity vaccine” against the pandemic-induced market selloff (Willis, 2020).3 Similar claims have been made for the COVID year 2020 as a whole (e.g., Hale, 2021b). Following this early pandemic hyping of ESG as downside risk protection, there was no surprise in CNBC's report that the first quarter of 2020 saw record inflows into sustainable funds (Stevens, 2020), nor that this demand continued to intensify as the year evolved (Hale, 2021a).4 Despite this high level of enthusiasm for ESG-tilted investments, however, by the middle of 2020 skepticism had emerged about whether ESG really was an effective returns shield during the crisis.5 By early 2021, critics were claiming that ESG scores are an outdated concept, and that the time for relying on such “blunt aggregation” had passed (Steffen, 2021).

Our study sheds light on the debate over whether ESG performance is a share price resilience factor during the COVID-19 pandemic. For a sample of US firms, we present robust evidence that ESG is not an “equity vaccine” against declining share prices in times of crisis, whether the period being examined is the market's implosion during the onset of the pandemic in the first quarter of 2020, or the full year ending in December of 2020. Rather, accounting-based measures of the firm's liquidity and leverage, financial performance, supply chain management and internally developed intangible assets, combined with the firm's industry affiliation and traditional market-based measures of equity risk, together explain well COVID period stock returns. Whereas ESG is incrementally insignificant in fully specified regressions, both for the first quarter of 2020 market implosion and for 2020 as a whole, a measure of the firm's stock of internally developed intangible assets is a statistically significant and economically important variable in explaining returns during both of these periods of the pandemic. Importantly, given the growing concerns over inconsistencies across commercial ESG databases (Berg et al., 2020, 2021), our results are robust to using the Refinitiv and MSCI data that would have been available to market participants at the onset of the COVID crisis in early 2020, as well as to the restated Refinitiv data (“Refinitiv II”) that became available in April of 2020.

The notion that ESG activities will contribute to stock price resilience during periods of crisis is premised upon the belief that corporate social responsibility activities help to build social capital and trust in the corporation, and that these bonds, in turn, will motivate the company's stakeholders (employees, customers, suppliers, financiers, government, society, etc.) to remain loyal, helping the company to rise above the challenges imposed by a crisis.6 Several studies of the 2008–2009 global financial crisis (“GFC”) period and two early studies related to the COVID pandemic suggest that ESG performance may indeed offer such downside risk protection in times of crisis (Albuquerque et al., 2020; Bouslah et al., 2018; Cornett et al., 2016; Ding et al., 2020; Lins et al., 2017).7 However, Berkman et al. (2020) present evidence from the GFC period to suggest that the Lins et al. (2017) results may not be robust to using alternative returns measures nor to examining non-US firms. Our findings robustly refute the importance of ESG in explaining stock returns for US equity securities during the recent pandemic, suggesting that earlier GFC period findings of ESG as a resilience factor are also not consistent across crises, and thus call into question the robustness of the “risk management” perspective of ESG as a protection against downside risk.

An agency theory perspective of corporate ESG investments suggests the opposite, which is that ESG-related activities may destroy value. This point of view holds that executives may choose to improve their company's ESG scores at the expense of shareholders in order to build their own personal reputations. From this perspective, ESG investments are at best wasteful and potentially harmful to shareholders (e.g., increasing the propensity for management entrenchment and the ensuing value destruction). This suggests that ESG scores will not be positively associated with share prices, but to the extent that such investments reflect poor management and/or agency problems, such indicators of corporate social responsibility could be a hindrance to a firm's resilience during challenging times, and would thus be negatively associated with crisis period returns.

A third possibility is that ESG scores will not be associated with stock returns during this period of crisis (i.e., neither the positive “risk management” nor negative “agency theory” predictions hold). This would arise if either ESG scores fail to reliably measure the alleged social capital that environmentally and societally friendly firms have accrued through their CSR initiatives, or if the well-measured social capital derived from such initiatives just does not lead to increased share price resilience. In either such case, this would manifest in ESG scores that are insignificant in crisis period regressions while more traditional indicators such as profitability, liquidity and/or low debt levels will be the key determinants of a firm's resilience during severe economic downturns, as has been established in the prior literature in other contexts (e.g., Bernanke & Gertler, 1989; Bhattacharya et al., 2010). In the context of recent global crises, a number of studies have documented that firms with weaker balance sheets at the start of the GFC were affected more by that crisis (e.g., Kahle & Stulz, 2013), while contemporaneous studies present evidence to suggest that cash and debt levels were important to stock price resilience during the market decline induced by the COVID pandemic (Albuquerque et al., 2020; Ramelli & Wagner, 2020). Ultimately, whether ESG will be positively, negatively or insignificantly associated with returns during the COVID crisis remains an empirical question that we thoroughly address in this study.

We undertake a series of analyses to investigate whether ESG is an important determinant of COVID period returns either instead of, or incrementally to, more traditional accounting- and market-based measures of risk. We first perform a multiple regression analysis of stock returns from the first quarter of 2020, a period during which market returns were significantly negative and that we refer to as the “crisis” period. Specifically, we regress buy-and-hold abnormal returns on the firm's ESG scores, after controlling for other factors such as accounting-based measures of financial performance, liquidity, leverage, supply chain management, intangible asset investments, variables capturing institutional investor interest and shareholder orientation, firm age and market share, the firm's industry affiliation, as well as a full array of market-based risk factors that are known determinants of returns. As expected, our results show that COVID Q1 crisis returns are associated with the firm's leverage and cash positions, a measure of its supply chain management, its reporting timeliness, as well as with industry sector indicators and numerous market-based measures of risk. Contrary to the findings of contemporaneous studies that do not include a full set of controls (Albuquerque et al., 2020; Ding et al., 2020), as well as to the widespread claims by fund managers, ESG data purveyors and other pundits, our results provide robust evidence that ESG scores are not significantly associated with stock market performance during the first quarter of 2020 once the full array of other expected determinants of returns have been controlled for. By contrast, COVID crisis returns are positively associated with a measure of the firm's stock of internally developed intangible assets, even after industry controls have been included, and this association is both statistically and economically significant. Together these findings suggest that investments in innovation-related intangible assets, rather than measures of the firms’ social capital investments, offer greater immunity to sudden, unanticipated market declines.

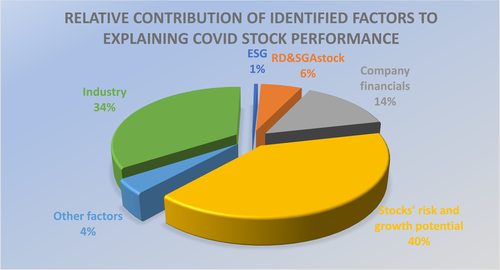

To further substantiate the irrelevance of ESG scores in determining crisis period stock price resilience, we undertake an Owen–Shapley decomposition (Huettner & Sunder, 2012) of the explained variation in returns (i.e., the returns regression model's R2). As shown in Figure 1, the results of these analyses indicate that three groups of explanatory variables offer almost all of the model's explanatory power for returns: market-based risk variables, industry fixed effects and accounting-based measures capturing the firm's performance, liquidity, leverage and its stock of internally generated intangible assets. Other variables contribute very little to the model's explanatory power, and ESG is responsible for a meagre 1% of the total explained variation.

Owen–Shapley R2 decomposition analysis COVID Q1 2020 crisis period

Notes: The pie chart in this figure represents the contribution of ESG, RD&SGAstock, company financials, stocks’ risk and growth potential, industry, and other factors to our COVID Q1 2020 Crisis period model R2 (Table 4). Company financials consists of: Cash, LTDebt, STDebt, ROA, Loss, InvTurn, AcqIntang, DivPayout, ICWeakness, MeanAnnSpeed, Size, and RD&SGAstock, although we break out the latter variable separately. Stocks’ risk and growth potential consists of: BTM, BTMNeg, Momentum, IdioRisk, MKTRF, HML, SMB, and MOM. Other factors consist of: Analyst, Mktshare, Age, InvestorOrient, InstOwners, and lnCEOtenure. All percentages are rounded to the nearest integer [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Notwithstanding ESG's failure to perform in its acclaimed role as a resilience factor during the initial pandemic-driven market meltdown in Q1 of 2020, we offer corporate social responsibility an opportunity to emerge as a positive returns factor over a longer period of the pandemic. Specifically, we examine the relation between ESG scores and, alternatively, abnormal returns for the entire year of 2020 and returns from February 24, 2020 (i.e., the date on which global markets began to significantly impound the implications of the virus (Ramelli & Wagner, 2020), through to the end of 2020. The results from the full COVID year 2020 period are consistent with those from the first quarter; ESG is insignificant as an explanatory variable for returns when a full set of accounting and market-based controls are included in the regressions, whereas the firm's stock of investments in internally generated intangibles is a positive and economically and statistically significant explanatory variable for returns. The findings of ESG insignificance for the full year of 2020 are surprising for a number of reasons.

First, they contradict recent claims that high ESG stock portfolios outperformed peer firms for the full year of 2020 (Hale, 2021b). Second, they call into question the external validity of prior GFC period findings that ESG is a resilience factor during difficult times as the result does not hold in the immediately subsequent global crisis. Finally, ESG is not positively associated with returns even during this period that saw record amounts of inflows into sustainable investments, a large portion of which occurred in the latter part of the year (Hale, 2021a). Thus, despite the likely price pressures manifesting from these dramatic recent shifts in investor preferences for higher ESG performing firms (Cornell, 2021), ESG was not a positive driver of COVID period returns.

Our results are robust to a battery of specification checks, including: using raw returns or the natural log of buy-and-hold abnormal returns as the dependent variable; adopting alternative regression specifications; using Refinitiv, Refinitiv II, or MSCI data to capture the firm's ESG performance; considering only ES as the relevant measure of the firm's CSR performance; and defining high ESG performers to be only those in the highest decile or quintile under the assumption that the continuous measures are noisy and vulnerable to “greenwashing”, whereas those in the highest percentiles of the ESG distribution are likely to be “truly” socially and environmentally high performing. The robustness of our findings to numerous alternative measures of ESG suggests that the observed lack of association between ESG and returns during the COVID-19 crisis is more likely to be due to a lack of underlying economic relation rather than to noisy data, but we cannot definitively rule out the possibility that all three datasets and the numerous permutations of ES and ESG performance derived there from capture poorly the nebulous underlying construct of interest.

Taken together, our analyses provide robust evidence that, contrary to the role of ESG as a resilience factor during the GFC and to widespread claims that it was also a share price vaccine during the 2020 COVID crisis, ESG was not significantly associated with returns during the 2020 global pandemic. Rather, industry affiliation, common market-based risk proxies and traditional accounting-based measures are all significant in explaining COVID period returns.

Perhaps most surprisingly, a measure of the firm's stock of investments in internally generated intangible assets is positively associated with share price performance, and this association is significant both statistically and economically for returns measured over each of the Q1 2020 market crisis period, as well as for the longer period of the pandemic through to the end of 2020. We conclude that, although ESG did not immunize share prices during the COVID-19 crisis, investments in intangible assets did.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a background discussion related to ESG and firm performance, both generally and in times of crisis. Section 3 describes our sample and data. In Section 4 we present our empirical methodologies and results, while Section 5 concludes this paper.

2 BACKGROUND

The notion that investments in the realm of ESG will enhance shareholder value—that is, “doing good is good for business”—in normal times, and even more so in times of crisis, remains a topic of considerable debate, both in academia and in the practical world of investments.

Proponents of ESG claim that such investments help to build social capital for, and trust in, the corporation. They argue that socially and environmentally responsible corporate behavior leads to the creation of important bonds between the firm and its stakeholders (i.e., employees, customers, providers of finance, the communities in which the company serves or operates, suppliers, governmental units, etc.), and that such goodwill will particularly pay off in periods of crisis. This “risk management” view of corporate social responsibility postulates that ESG investments serve as a form of insurance-like protection against downside risk (Godfrey et al., 2009).

Several academic studies focusing on the 2008 to 2009 global financial crisis (“GFC”) period find evidence to support the case for ESG as a mitigator of downside risk. Cornett et al. (2016) find that banks appear to be rewarded for being socially responsible, as evidenced by ROE being positively and significantly related to CSR scores. These authors further suggest that post-GFC amplified participation in CSR activities is therefore likely to lead to a lower probability of future crashes. For a sample of US non-financial firms, Bouslah et al. (2018) find that CSR reduces volatility during the financial crisis, and furthermore that this risk reduction is mainly due to the strengths rather than the concerns component of social performance.

Consistent with the bonding and risk mitigation perspective, these authors conclude that CSR strengths act as a risk reduction tool during an adverse economic environment. Lins et al. (2017) present evidence to suggest that US non-financial firms that had higher social capital (i.e., measured using CSR scores) enjoyed stock returns during the GFC period that were 4% to 7% higher than those with lower social capital, and that high CSR firms also experienced higher profitability, growth and sales per employee, and that they raised more debt. These authors conclude that the trust between a firm and its stakeholders and shareholders, built through investments in CSR, pays off when the overall level of trust in companies and markets suffers a negative shock.8 Recently, however, Berkman et al. (2020) have questioned the robustness of the Lins et al. (2017) finding to alternative measures of returns, as well as its generalizability to the context of non-US firms.9

An alternative view on corporate ESG investments derives from agency theory. This more skeptical perspective suggests that executives may choose to improve their company's ESG scores at the expense of shareholders in order to build their own personal reputations.10 Because this reputational enhancement leads to a reduced likelihood of turnover, the executive's social capital investments on behalf of the firm form part of the executive's entrenchment strategy (Surroca & Tribó, 2008). To the extent that such ESG-related investments lead to managerial entrenchment and/or are wasteful managerial self-serving expenditures funded from corporate coffers, they could be shareholder value-destroying. Consistent with this, Lys et al. (2015) show that ESG expenditures generate insufficient returns and hence reduce shareholder value. These authors conclude instead that ESG investments appear to be a channel through which a company communicates its financial prospects (i.e., the undertaking of CSR initiatives is a signal that the firm's management is anticipating stronger future performance), but that they do not create value for the typical business. In the context of an exogenous and extreme negative shock, the expected informativeness of this signal for the firm's future prospects would surely be revised, and a firm's expenditures on ESG may even be seen as wasteful extravagances that will not help the firm to withstand the challenges of the crisis. From this perspective, higher investments in ESG may result in socially responsible firms becoming more vulnerable in times of crisis.

Several contemporaneous studies have investigated the relation between ESG scores and firms’ stock price resilience during the current COVID crisis. Using a global sample of over 6,000 companies from 56 economies, Ding et al. (2020) find that firms’ pandemic-induced share price reductions were decreasing in their 2018 ESG scores. This study's analyses do not seem to control either for traditional market-based measures of risk, nor for numerous other variables that our data show are highly correlated with returns and firms’ ESG scores (i.e., their regressions are likely to suffer from a correlated omitted variable bias). In addition, their results are for a global sample consisting of mostly non-US firms, while ESG is known to have a more positive impact on returns in non-US jurisdictions where corporate social and environmental performance is much more salient, such as in Europe (Amel-Zadeh & Serafeim, 2018). Accordingly, their results are not directly generalizable to the US-only setting that we study.

The primary US-based study that we are aware of that is most closely related to ours is by Albuquerque et al. (2020). These authors implicitly assume that only the environmental and social (“ES”) pillars of the traditional ESG combined score will be relevant for COVID crisis period resilience, but otherwise use the same Refinitiv EIKON data that we primarily rely on to test their claim. They find that ES is statistically and economically significant in regressions that contain a small set of accounting-based control variables, together with industry fixed effects.

We replicate the findings that they report in their Table 2 and confirm that ES and ESG are each significant in separate specifications that include the same limited set of controls considered by Albuquerque et al. (2020). By comparison, however, our reported returns regressions include several additional market-based, accounting-based, and other control variables that we find to be significantly correlated with ESG in a very similar sample and dataset to that used by those authors.11 With the inclusion of these additional controls, some of which our forthcoming regressions reveal to be highly significant determinants of returns, the significance of either ES or ESG as a determinant of COVID-19 crisis period returns definitively vanishes in both Q1 and full year 2020 returns regressions. In other words, by avoiding a correlated omitted variables bias, we arrive at opposite conclusions regarding the role of ESG (or ES) as a share price resilience factor during the COVID crisis.12

3 DATA, SAMPLE, VARIABLE MEASUREMENT AND DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS

3.1 Data and sample

We obtain accounting information from the Compustat quarterly and annual databases, and stock market returns data from CRSP. Internal control weaknesses are taken from the Audit Analytics dataset, while institutional ownership data is derived from the Thomson Reuters 13f database. I/B/E/S data is the source of our analyst following measure, and the CEO tenure variable comes from the BoardEx database. Fama–French factors are obtained from Kenneth French's website.13 Measures of investor orientation are calculated using data from the Thomson Reuters 13f database merged with investor classification data obtained from Brian Bushee's website.14 In addition, we manually collected some executive start dates that were identified as missing in order to maximize the available sample.

Refinitiv's pre-April 2020 EIKON database is the primary source of our environmental, social and governance (ESG) scores for the COVID-19 analyses, reflecting the data that would have been available to the market at the onset of the pandemic. In light of current controversies regarding inconsistent rankings across commercial ESG data providers (Berg et al., 2020), we also replicate our findings using MSCI data for 2018 (i.e., the most recent data that would have been available in early 2020 at the onset of the pandemic). Finally, in light of the revelation that Refinitiv restated its data in April 2020 in a manner that made it historically more highly correlated with returns (Berg et al., 2021), we also verify that our key results hold using this revised data, which we refer to as “Refinitiv II.”15

In order to construct our primary dataset, we begin with all firm-year observations for which a Refinitiv ESG score is available for fiscal 2018, the last annual reporting period included in the database for most firms prior to the onset of the COVID crisis. We restrict our sample to US companies, and we drop all financial and real estate firms from our tests. We also drop all observations that have an undue influence on the determination of the coefficients in the fully specified returns regression (i.e., Model 1 introduced below).16 This results in a sample of 1652 firms for which all requisite data is available for our tests of the Q1 2020 COVID crisis period. Due to the removal of additional influential observations, the sample declines to 1642 firms for the full year returns analyses. Further details on the sample determination process are provided in Table 1.

| Refinitiv EIKON ESG data | |

|---|---|

| Number of observations for FY 2018 | 2312 |

| Dropping: | |

| Non-US firms | −42 |

| Duplicates | −1 |

| Merging stage | −27 |

| SIC code 6000 - 6999 | −568 |

| Missing data | −13 |

| Influential observations Cook's distance > 0.01 | −9 |

| Number of sample firms for Q1 | 1652 |

| Additional observations Cook's distance > 0.01 full year | −10 |

| Number of sample firms full year 2020 | 1642 |

3.2 Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics for our sample firms are provided in Table 2A for Q1 and Table 2B for the full year sample. In light of the highly overlapping nature of the samples, only the returns variables differ materially across the two panels. Given the relatively large firm bias of some of the databases being used for our analyses, sample firms tend to be somewhat larger, on average, than the CRSP-Compustat universe. The average (median) firm has been established for 28 (24) years and has nearly 10 (8) analysts providing earnings estimates for it. Twenty-one percent of sample firms reported negative earnings for fiscal 2019, while the average (median) firm's adjusted ROA for that year was approximately 3.3% (4.4%). The average abnormal buy-and-hold (raw) returns during the Q1 crisis period were −5.6% (−31.4%), which improved to −4.6% (20.6%) for the full year of 2020. The mean (median) overall Refinitiv ESG summary score for sample firms is approximately 47 (43) out of a theoretical maximum of 100, the interquartile range is about 25, and the full range of this variable for our sample firms is 7 to 95 (untabulated), all suggesting that there is a good deal of cross-sectional variation in the test variable of interest.

| Panel A: Summary statistics COVID Q1 2020 crisis period | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | N | Mean | Std. dev. | p25 | Median | p75 |

| BHAR | 1652 | −0.056 | 0.232 | −0.205 | −0.055 | 0.070 |

| RawReturn | 1652 | −0.314 | 0.235 | −0.472 | −0.312 | −0.157 |

| ESG | 1652 | 46.655 | 17.320 | 33.543 | 43.372 | 58.158 |

| ESG_MSCI | 1606 | 0.480 | 0.543 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.683 |

| ESG_ReftvII | 1694 | 37.420 | 18.878 | 22.684 | 33.163 | 48.775 |

| Cash | 1652 | 0.134 | 0.144 | 0.028 | 0.079 | 0.184 |

| LTDebt | 1652 | 0.240 | 0.181 | 0.090 | 0.225 | 0.349 |

| STDebt | 1652 | 0.024 | 0.037 | 0.004 | 0.010 | 0.030 |

| ROA | 1652 | 0.032 | 0.087 | 0.011 | 0.044 | 0.077 |

| Loss | 1652 | 0.209 | 0.407 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| InvTurn | 1652 | 0.643 | 1.029 | 0 | 0.396 | 0.782 |

| RD&SGAstock | 1652 | 0.214 | 0.162 | 0.082 | 0.185 | 0.312 |

| AcqIntang | 1652 | 0.194 | 0.193 | 0.020 | 0.137 | 0.331 |

| DivPayout | 1652 | 0.156 | 0.608 | 0 | 0 | 0.308 |

| ICweakness | 1652 | 0.124 | 0.515 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MeanAnnSpeed | 1652 | −0.099 | 0.020 | −0.114 | −0.101 | −0.086 |

| Size | 1652 | 7.89 | 1.647 | 6.712 | 7.767 | 8.920 |

| BTM | 1652 | 0.412 | 0.476 | 0.147 | 0.306 | 0.541 |

| BTMneg | 1652 | 0.057 | 0.232 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Momentum | 1652 | 0.259 | 0.472 | −0.017 | 0.227 | 0.473 |

| IdioRisk | 1652 | 0.109 | 0.060 | 0.064 | 0.093 | 0.136 |

| SMB | 1652 | 0.786 | 1.007 | 0.162 | 0.647 | 1.266 |

| HML | 1652 | −0.011 | 1.014 | −0.453 | 0.062 | 0.543 |

| MOM | 1652 | −0.065 | 0.693 | −0.383 | −0.042 | 0.297 |

| MKTRF | 1652 | 1.060 | 0.619 | 0.667 | 1.042 | 1.394 |

| Analyst | 1652 | 9.714 | 7.418 | 4 | 8 | 14 |

| MktShare | 1652 | 0.026 | 0.062 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.018 |

| Age | 1652 | 27.933 | 19.918 | 10 | 24 | 38 |

| Age2 | 1652 | 1176.779 | 1475.457 | 100 | 576 | 1444 |

| InvestorOrient | 1652 | −1.667 | 8.066 | −5.653 | −0.650 | 2.930 |

| InstOwners | 1652 | 67.643 | 21.566 | 59.282 | 72.374 | 81.477 |

| lnCEOtenure | 1652 | 6.689 | 1.680 | 6.184 | 7.027 | 7.679 |

| Panel B: Summary statistics full year 2020 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | N | Mean | Std. dev. | p25 | Median | p75 |

| BHAR | 1642 | −0.046 | 0.605 | −0.365 | −0.132 | 0.112 |

| RawReturn | 1642 | 0.206 | 0.609 | −0.126 | 0.095 | 0.397 |

| ESG | 1642 | 46.650 | 17.338 | 33.542 | 43.348 | 58.253 |

| ESG_MSCI | 1596 | 0.485 | 0.542 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.706 |

| ESG_ReftvII | 1686 | 37.387 | 18.895 | 22.523 | 33.133 | 48.775 |

| Cash | 1642 | 0.134 | 0.144 | 0.028 | 0.079 | 0.183 |

| LTDebt | 1642 | 0.240 | 0.180 | 0.091 | 0.225 | 0.349 |

| STDebt | 1642 | 0.024 | 0.037 | 0.004 | 0.010 | 0.030 |

| ROA | 1642 | 0.033 | 0.087 | 0.012 | 0.044 | 0.077 |

| Loss | 1642 | 0.206 | 0.405 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| InvTurn | 1642 | 0.640 | 1.020 | 0 | 0.395 | 0.782 |

| RD&SGAstock | 1642 | 0.213 | 0.161 | 0.082 | 0.185 | 0.311 |

| AcqIntang | 1642 | 0.195 | 0.193 | 0.021 | 0.138 | 0.332 |

| DivPayout | 1642 | 0.154 | 0.602 | 0 | 0 | 0.310 |

| ICweakness | 1642 | 0.125 | 0.518 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MeanAnnSpeed | 1642 | −0.099 | 0.020 | −0.114 | −0.101 | −0.086 |

| Size | 1642 | 7.901 | 1.647 | 6.713 | 7.767 | 8.926 |

| BTM | 1642 | 0.414 | 0.478 | 0.147 | 0.309 | 0.541 |

| BTMneg | 1642 | 0.056 | 0.230 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Momentum | 1642 | 0.260 | 0.468 | −0.014 | 0.227 | 0.472 |

| IdioRisk | 1642 | 0.108 | 0.059 | 0.064 | 0.092 | 0.135 |

| SMB | 1642 | 0.789 | 1.002 | 0.166 | 0.654 | 1.266 |

| HML | 1642 | −0.004 | 1.011 | −0.449 | 0.065 | 0.551 |

| MOM | 1642 | −0.063 | 0.692 | −0.382 | −0.039 | 0.297 |

| MKTRF | 1642 | 1.060 | 0.616 | 0.669 | 1.043 | 1.389 |

| Analyst | 1642 | 9.741 | 7.456 | 4 | 8 | 14 |

| MktShare | 1642 | 0.026 | 0.063 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.018 |

| Age | 1642 | 28.019 | 19.958 | 10 | 24 | 38 |

| Age2 | 1642 | 1183.171 | 1478.681 | 100 | 576 | 1444 |

| InvestorOrient | 1642 | −1.688 | 8.020 | −5.697 | −0.660 | 2.937 |

| InstOwners | 1642 | 67.750 | 21.435 | 59.321 | 72.391 | 81.527 |

| lnCEOtenure | 1642 | 6.697 | 1.679 | 6.190 | 7.052 | 7.684 |

- Note: All variables are defined in detail in the Appendix. Institutional ownership is truncated at 100%, ESG is left unaltered and all other continuous variables are winsorized at the 1% and 99% level.

Panels A and B of Table 3 present the pairwise Pearson correlations between select regression variables for each of Q1 and the full year, respectively. As shown in Panel A, Cash and RD&SGA stock are the two fundamental variables that are most significantly positively correlated with firms’ buy-and-hold abnormal returns (BHAR) for Q1 2020, while short- and long-term debt are those most significantly negatively correlated with Q1 returns. These simple pairwise correlations confirm our expectations that firms with a lot of liquidity and innovation-driven assets are more resilient during the market implosion, whereas those with more significant debt burdens are less so. For the full COVID year, Panel B reveals that RD&SGA stock is again the variable that is most highly correlated with BHAR, while Cash and LTDebt continue to exhibit significant, albeit diminished, positive and negative correlations with BHAR, respectively. ROA and Size are surprisingly significantly negatively correlated with returns for the full year period. In unreported tabulations (for parsimony) we find that traditional market-based measures of risk are also highly significantly associated with abnormal returns.

| Panel A: Pearson correlations COVID Q1 2020 crisis period | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | (16) | (17) |

| (1) BHAR | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| (2) RawReturn | 0.80 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| (0.00) | |||||||||||||||||

| (3) ESG | 0.05 | 0.07 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| (0.04) | (0.00) | ||||||||||||||||

| (4) Cash | 0.27 | 0.26 | −0.19 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |||||||||||||||

| (5) LTDebt | −0.25 | −0.26 | 0.11 | −0.40 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | ||||||||||||||

| (6) STDebt | −0.11 | −0.09 | 0.08 | −0.18 | 0.12 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |||||||||||||

| (7) ROA | −0.03 | 0.16 | 0.18 | −0.22 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| (0.22) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.15) | (0.19) | ||||||||||||

| (8) InvTurn | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.09 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| (0.47) | (0.85) | (0.05) | (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.11) | (0.50) | |||||||||||

| (9) RD&SGAstock | 0.28 | 0.20 | −0.13 | 0.44 | −0.45 | −0.12 | −0.33 | −0.06 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.02) | ||||||||||

| (10) MeanAnnSpeed | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.40 | −0.22 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.39 | 0.03 | −0.15 | 1.00 | |||||||

| (0.23) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.98) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.23) | (0.00) | |||||||||

| (11) Size | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.58 | −0.14 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.47 | 0.01 | −0.25 | 0.54 | 1.00 | ||||||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.69) | (0.00) | (0.00) | ||||||||

| (12) Analyst | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.50 | −0.05 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.23 | 0.00 | −0.06 | 0.42 | 0.73 | 1.00 | |||||

| (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.05) | (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.91) | (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |||||||

| (13) BTM | −0.16 | −0.33 | −0.07 | −0.24 | −0.06 | −0.01 | −0.17 | −0.02 | −0.27 | −0.09 | −0.30 | −0.16 | 1.00 | ||||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.74) | (0.00) | (0.31) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | ||||||

| (14) Momentum | 0.12 | 0.16 | −0.01 | 0.09 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.16 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.30 | 0.08 | −0.34 | 1.00 | |||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.58) | (0.00) | (0.16) | (0.60) | (0.00) | (0.92) | (0.72) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |||||

| (15) IdioRisk | 0.10 | −0.12 | −0.35 | 0.45 | −0.15 | −0.11 | −0.52 | −0.03 | 0.45 | −0.52 | −0.55 | −0.27 | 0.09 | −0.03 | 1.00 | ||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.20) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.16) | ||||

| (16) InstOwners | −0.08 | −0.09 | 0.17 | −0.12 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.01 | −0.12 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.24 | 1.00 | |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.33) | (0.00) | (0.82) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.50) | (0.13) | (0.00) | |||

| (17) InvestorOrient | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.22 | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.07 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.09 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.18 | −0.08 | 1.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.31) | (0.68) | (0.67) | (0.98) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.65) | (0.35) | (0.00) | (0.00) | ||

| Panel B: Pearson correlations full year 2020 | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | (16) | (17) |

| (1) BHAR | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| (2) RawReturn | 0.90 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| (0.00) | |||||||||||||||||

| (3) ESG | −0.05 | −0.08 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| (0.05) | (0.00) | ||||||||||||||||

| (4) Cash | 0.10 | 0.24 | −0.19 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |||||||||||||||

| (5) LTDebt | −0.08 | −0.15 | 0.11 | −0.40 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | ||||||||||||||

| (6) STDebt | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.18 | 0.12 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| (0.96) | (0.23) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |||||||||||||

| (7) ROA | −0.13 | −0.02 | 0.18 | −0.22 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| (0.00) | (0.40) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.15) | (0.20) | ||||||||||||

| (8) InvTurn | −0.03 | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.09 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| (0.19) | (0.08) | (0.05) | (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.09) | (0.70) | |||||||||||

| (9) RD&SGAstock | 0.24 | 0.28 | −0.14 | 0.44 | −0.45 | −0.12 | −0.32 | −0.07 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.01) | ||||||||||

| (10) MeanAnnSpeed | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.40 | −0.22 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.38 | 0.04 | −0.14 | 1.00 | |||||||

| (0.21) | (0.30) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.90) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.15) | (0.00) | |||||||||

| (11) Size | −0.10 | 0.01 | 0.58 | −0.14 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.47 | 0.01 | −0.24 | 0.54 | 1.00 | ||||||

| (0.00) | (0.68) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.56) | (0.00) | (0.00) | ||||||||

| (12) Analyst | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.49 | −0.05 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.23 | 0.00 | −0.06 | 0.42 | 0.73 | 1.00 | |||||

| (0.57) | (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.06) | (0.00) | (0.02) | (0.00) | (0.99) | (0.02) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |||||||

| (13) BTM | 0.01 | −0.16 | −0.06 | −0.24 | −0.05 | 0.00 | −0.17 | −0.02 | −0.28 | −0.09 | −0.30 | −0.16 | 1.00 | ||||

| (0.81) | (0.00) | (0.02) | (0.00) | (0.04) | (0.89) | (0.00) | (0.41) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | ||||||

| (14) Momentum | −0.11 | 0.12 | −0.01 | 0.09 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.08 | −0.35 | 1.00 | |||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.66) | (0.00) | (0.18) | (0.60) | (0.00) | (0.94) | (0.96) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |||||

| (15) IdioRisk | 0.10 | 0.16 | −0.36 | 0.45 | −0.16 | −0.11 | −0.53 | −0.04 | 0.45 | −0.51 | −0.56 | −0.27 | 0.09 | −0.04 | 1.00 | ||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.09) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.13) | ||||

| (16) InstOwners | −0.04 | −0.03 | 0.17 | −0.12 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.01 | −0.11 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.23 | 1.00 | |

| (0.16) | (0.21) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.31) | (0.00) | (0.62) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.36) | (0.17) | (0.00) | |||

| (17) InvestorOrient | −0.03 | −0.06 | 0.22 | −0.07 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.07 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.09 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.19 | −0.08 | 1.00 |

| (0.30) | (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.18) | (0.87) | (0.49) | (0.68) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.50) | (0.41) | (0.00) | (0.00) | ||

Consistent with widespread reports in early 2020 that ESG was a resilience factor during the Q1 market implosion, the correlations reported in Panel A suggest that ESG scores and abnormal returns are positively correlated, albeit not nearly as strongly as the previously mentioned cash, internal investments in intangible assets, and some of the market-related risk factors, nor as statistically significantly as the negative correlations found for the debt variables. Contrary to similar claims of ESG outperformance for the full year of 2020, however, the correlation between ESG and each of BHAR and raw returns is negative over this longer period. In other words, even the pairwise correlations do not support the claims that ESG was a resilience factor for the full COVID year of 2020. It remains to be seen whether the association between ESG and returns will be significant for either period once the competing fundamental accounting and market risk factors are simultaneously incorporated into a multiple regression analysis. We turn to this next.

4 EMPIRICAL RESULTS

4.1 What explains returns during the COVID-19 Q1 2020 crisis period?

For our primary tests, ESG is measured using Refinitiv's pre-April 2020 overall summary score of ESG performance. Although some prior studies focus only on the ES portion of Refinitiv's ESG score under the assumption that these are the components that best capture the social capital that is purported to lead to resilience, we consider Refinitiv's comprehensive ESG score to be the most appropriate measure for our tests. Our reasoning relies upon a review of the subcomponents included in Refinitiv's “G”, or the governance pillar, of the total ESG score.

These include variables designed to capture board and executive gender and cultural diversity (i.e., arguably as much “S” as “G”), an indicator for whether the firm is reporting under GRI standards and the percentage of the firm's activities covered in its E&S reporting (i.e., impacting both “E” and “S” measurement), as well as numerous other variables that border upon, or are intimately intertwined with, the E and S dimensions of corporate sustainability.18

We control for the firm's liquidity and leverage with Cash, LTDebt and STDebt and for accounting-based performance with ROA and the Loss indicator variable. Given widespread concerns regarding supply chain issues during the early months of the pandemic, we include the industry-adjusted inventory turnover ratio (InvTurn), measured following the approach suggested by Platt and Platt (1991), to capture this dimension of the firm's performance.

We also include variables to capture the firm's past investments in acquired and internally developed intangible assets, AcqIntang and RD&SGAstock, respectively.

RD&SGAstock is a measure designed to capture the notion that, although required to be expensed under US GAAP, firm expenditures on R&D, as well as some portion of expenditures on SG&A, are actually investments in internally developed intangible assets. More specifically, the calculation of RD&SGAstock assumes that all R&D expenses and an assumed rate of ⅓ of SG&A expenses represent investments in intangible assets that will have a five-year life. We use the assumed rate of ⅓ of SG&A as a conservative estimate of the “investment” portion of SG&A expenditures although this rate has been growing over time (Enache & Srivastava, 2018). We notionally capitalize these expenditures and amortize them linearly over a five-year period, which is also a conservative estimate of the duration of these benefits (Lev & Sougiannis, 1996). So, for example, RD&SGAstock for fiscal 2019 = FY2019 (R&D + ⅓SGA)*100% + FY2018 (R&D + ⅓SGA)*80% + FY2017 (R&D + ⅓SGA)*60% + FY2016 (R&D + ⅓SGA)*40% + FY2015 (R&D + ⅓SGA)*20%.

Additional control variables include the firm's dividend payout ratio (DivPayout), Size, market share (MktShare) and the number of years since the firm first appeared in Compustat (Age), allowing the latter to enter non-linearly with the inclusion of Age2. We control for the firm's reporting timeliness and quality by including the average earnings announcement speed over the prior four quarters (MeanAnnSpeed) (Gallemore & Labro, 2015) as well as a count of internal control weaknesses noted in the most recent fiscal year available prior to the crisis (ICweakness). We capture investor horizon (InvestorOrient) using the measure proposed by Serafeim (2015), while InstOwners is the average percentage of institutional investors in the firm's stock, truncated at 100% consistent with Gompers and Metrick (2001). Analyst is the firm's analyst following, a measure designed to capture the firm's information environment, and lnCEOtenure is the natural log of the length of the CEO's tenure with the firm measured in days. Market-based measures of risk and/or growth opportunities include the book-to-market ratio (BTM), an indicator set to one if BTM is negative (BTMneg), prior stock price momentum (Momentum), idiosyncratic risk (IdioRisk), as well as the four Fama–French factor loadings (MKTRF, SMB, HML, MOM). All specifications also include industry fixed effects, where industries are defined using two-digit SIC codes. All variables other than InstOwners and ESG are winsorized at the top and bottom 1%, and each is defined in greater detail in the Appendix.

The results from estimating variants of Model 1 using the abnormal buy-and-hold returns from the first quarter of 2020 as the dependent variable are presented in Table 4. The specification in the first column includes only ESG and the industry indicators, while the regression in the second column also includes market-based measures of risk. Consistent with the early pandemic hype, ESG is significantly positively related to returns in each of these specifications, prior to other controls being included in the regression. As shown in column (3), when Size is added to the regression, this control variable is positive and significant, whereas the coefficient on ESG declines by more than half, and ESG is no longer significant at any conventionally acceptable level.19 These results suggest that the exclusion of a simple control and known determinant of returns (i.e., firm size) leads to incorrect inferences regarding the role of ESG as a determinant of returns.20

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BHAR | BHAR | BHAR | BHAR | BHAR | |

| ESG | 0.001243*** | 0.000824*** | 0.00033 | 0.000381 | 0.000475 |

| (0.000286) | (0.000297) | (0.000352) | (0.000348) | (0.000353) | |

| BTM | −0.036067** | −0.027781* | −0.012591 | −0.009872 | |

| (0.015499) | (0.015795) | (0.016103) | (0.016174) | ||

| BTMneg | −0.038901 | −0.031411 | 0.01987 | 0.018053 | |

| (0.025635) | (0.025605) | (0.02627) | (0.026166) | ||

| Momentum | −0.01331 | −0.021744 | −0.016401 | −0.0172 | |

| (0.014624) | (0.014478) | (0.01447) | (0.014962) | ||

| IdioRisk | −0.444985*** | −0.331325** | −0.515273*** | −0.539835*** | |

| (0.153089) | (0.165095) | (0.181443) | (0.190934) | ||

| SMB | 0.027223*** | 0.029305*** | 0.030888*** | 0.031816*** | |

| (0.007773) | (0.007893) | (0.007823) | (0.007868) | ||

| HML | −0.036339*** | −0.033548*** | −0.02456*** | −0.026621*** | |

| (0.008175) | (0.008419) | (0.008621) | (0.008865) | ||

| MOM | −0.03171*** | −0.034164*** | −0.054882*** | −0.053237*** | |

| (0.010573) | (0.010688) | (0.010896) | (0.010995) | ||

| MKTRF | 0.163351*** | 0.163923*** | 0.171806*** | 0.172514*** | |

| (0.011449) | (0.011376) | (0.011224) | (0.011221) | ||

| Size | 0.01214** | 0.009738* | 0.010961 | ||

| (0.005065) | (0.005475) | (0.007772) | |||

| Cash | 0.162544*** | 0.16806*** | |||

| (0.054666) | (0.054381) | ||||

| LTDebt | −0.189764*** | −0.17594*** | |||

| (0.04007) | (0.040338) | ||||

| STDebt | −0.224896* | −0.221183* | |||

| (0.132692) | (0.131185) | ||||

| ROA | 0.141036 | 0.158667 | |||

| (0.10823) | (0.109815) | ||||

| Loss | 0.00615 | 0.006595 | |||

| (0.021666) | (0.021715) | ||||

| InvTurn | 0.008745* | 0.008664* | |||

| (0.00493) | (0.004884) | ||||

| RD&SGAstock | 0.140916** | 0.140564** | |||

| (0.05808) | (0.05751) | ||||

| AcqIntang | 0.006903 | 0.005611 | |||

| (0.03213) | (0.032312) | ||||

| DivPayout | 0.005575 | 0.001947 | |||

| (0.008618) | (0.008719) | ||||

| ICweakness | 0.011046 | 0.011146 | |||

| (0.010067) | (0.009978) | ||||

| MeanAnnSpeed | 0.644227* | 0.635845* | |||

| (0.332409) | (0.33908) | ||||

| Analyst | −0.000325 | ||||

| (0.001065) | |||||

| MktShare | −0.016236 | ||||

| (0.076744) | |||||

| Age | 0.001076 | ||||

| (0.001051) | |||||

| Age2 | −0.000017 | ||||

| (0.000013) | |||||

| InvestorOrient | 0.001087 | ||||

| (0.000706) | |||||

| InstOwners | −0.000649** | ||||

| (0.000273) | |||||

| lnCEOtenure | −0.001178 | ||||

| (0.002605) | |||||

| _cons | 0.006006 | −0.06439 | −0.142433 | −0.059056 | −0.040581 |

| (0.072932) | (0.08287) | (0.087665) | (0.089415) | (0.102972) | |

| Observations | 1652 | 1652 | 1652 | 1652 | 1652 |

| R-squared | 0.240128 | 0.372372 | 0.374941 | 0.415637 | 0.421184 |

| Industry Dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

- Note: Robust standard errors are in parentheses.

- ***p < .01,

- **p < .05,

- *p < .10.

Column (4) presents the results from a more completely specified regression that includes fundamental accounting-based measures of performance, supply chain management, liquidity, leverage, investments in intangibles and financial reporting quality, while column (5) adds further control variables such as analyst following, firm age, CEO tenure, and share ownership characteristics. As shown, ESG remains insignificant in each of these specifications, whereas the coefficient signs, magnitudes, and significance levels of most of the other control variables remain largely consistent across models.

As shown in column (5), firms with higher levels of institutional ownership performed less well during the market downturn (i.e., InstOwners is negative and significant), a finding that is broadly consistent with the results reported in Glossner, Matos, Ramelli, and Wagner (2020). These authors show that institutional investor ownership falls more in firms with weak financials (i.e., lower cash holdings and higher leverage), which they interpret as institutional investors prioritizing financial strength over ESG performance in the face of the COVID-19 Q1 2020 tail risk event.

Although it is not surprising that idiosyncratic risk and the four Fama–French factors all remain statistically significant in explaining returns in this more fully specified regression, it is nevertheless notable that they do not dominate the more fundamental accounting-based measures of the firm's expected resilience or reporting quality. Specifically, the firm's inventory turnover rate (InvTurn), its level of cash stores (Cash) and its reporting timeliness (MeanAnnSpeed) are positive and significant determinants of returns during the crisis period, while the firm's short- term and long-term debt levels are negatively associated with returns. These results suggest that traditional accounting-based measures of the firm's reporting timeliness, supply chain management, liquidity and leverage are all important indicators of a company's share price resilience during the early days of the unexpected global COVID crisis although ESG is not.

RD&SGAstock, the measure of the firm's stock of innovative assets (i.e., the unamortized portion of the capitalized internally-developed R&D- and SG&A-related intangible assets) is also statistically and economically significant. The results from column (5) suggest that a one standard deviation increase in the stock of internally developed intangible assets is associated with an approximately 1.7% increase in abnormal returns during the Q1 2020 crisis period, or about 7% on an annualized basis.21 Overall, the results from the fully specified regressions in Table 4 clearly indicate that investments in intangible assets led to share price resilience during the Q1 2020 market crisis period of the COVID pandemic, whereas ESG performance did not.22

In untabulated specification checks, we confirm that the insignificance of ESG is not due to the inclusion of RD&SGAstock in the regression nor due to the associated remeasurement of net income and total assets resulting from the notional capitalization of R&D and (a portion of) SG&A expenses. In other words, our results are robust to using unadjusted net income in the calculation of ROA, using unadjusted total assets as the scalar, and to dropping RD&SGAstock from the regression. Thus, our combined findings of significance for RD&SGAstock and insignificance for ESG should not be interpreted as an indication that RD&SGAstock is serving as an alternative proxy for firms’ investments in CSR that somehow manages to dominate the ESG performance measures derived from commercial databases. Indeed, the negative pairwise correlations (of modest magnitudes) between ESG and RD&SGAstock presented in Table 3 further suggest that, statistically speaking, these two variables are not substitute proxies for the same underlying construct. Furthermore, practically speaking, it would be unlikely that RD&SGAstock would dominate ESG in capturing CSR performance given that the ESG scores are actually designed to capture performance (i.e., the outcomes of efforts and expenditures on CSR-related initiatives), whereas the RD&SGAstock measure derives from expenditures (i.e., inputs, only some of which are likely to be related to CSR initiatives, and not all of the latter are likely to have a positive pay off in terms of manifesting in higher CSR performance). In other words, RD&SGAstock does not emerge as the winner of a “horse race” between intangible asset investments and ESG because ESG becomes insignificant even in the absence of RD&SGAstock being in the regression. Instead, these two variables are capturing quite different elements of the firm's activities, of which only the investments in intangibles are a resilience factor during COVID-19.

In order to gain a better understanding of the relative importance of accounting, market, industry membership and other variables in explaining crisis period returns, we undertake an Owen-Shapley decomposition as explained by Huettner and Sunder (2012).23 Using this approach, we are able to estimate the proportion of the explanatory power for returns that each set of variables contributes. Table 4 reports that our most complete regression from column (5) explains approximately 42% of the overall cross-sectional variation in the Q1 COVID crisis period returns for the firms in our sample. Figure 1 presents a pie chart depicting the proportion of this 42% that is explained by each group of variables. As shown, the set of market-based measures contributes the most to the overall R2, with 40% of the explained variation being due to these variables. Industry membership is a relatively close second, accounting for 34% of the explained variation. Measures derived from the firms’ financial statements combined with measures of the firms’ financial reporting quality together account for 20% of the explained variation in stock returns, of which 6% is due to RD&SGAstock, while other variables (e.g., ownership characteristics, market share and firm age) contribute just 4% of the overall explanatory power. Most notable, however, is the finding that the ESG summary score is the least important category, contributing less than 1% of the total 42% explained variation in returns during the first quarter of the COVID crisis.

Taken together, our results from these regression analyses and the Owen-Shapley decomposition suggest that classic market-based determinants of returns, industry fixed effects, as well as financial statement variables that capture the firm's financial and supply chain performance, liquidity, leverage and investments in intangible assets are all important in explaining Q1 COVID crisis period stock returns, whereas ESG is not. We conclude that ESG was not a share price vaccine during the market's implosion in the early months of the global pandemic, but that investments in internally generated intangible assets were positively and economically significantly associated with share price resilience.

4.2 Determinants of returns for the full COVID year of 2020

Table 5 presents the results of the regressions from variants of Model 1 using the abnormal buy-and-hold returns from the full year of 2020 as the dependent variable. The overall explanatory power of the most complete model for this full year period is just 16.5%, which is considerably below the 42% of explained variation previously documented for the Q1 crisis period. In contrast to the findings for Q1, the full year return results presented in column (1) of Table 5 indicates that ESG is a weakly negative and significant determinant of returns in the absence of any additional market risk and accounting-based control variables being included in the regression. Once additional standard controls are added to the regressions in columns (2)–(4), ESG becomes insignificant as an explanatory variable for the full COVID year 2020 returns.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BHAR | BHAR | BHAR | BHAR | |

| ESG | −0.001257* | −0.000196 | −0.000235 | 0.000183 |

| (0.000711) | (0.000798) | (0.001006) | (0.001012) | |

| BTM | 0.096902** | 0.143884*** | 0.134427** | |

| (0.048647) | (0.053781) | (0.053547) | ||

| BTMneg | 0.059191 | −0.010513 | −0.009404 | |

| (0.079434) | (0.084635) | (0.083735) | ||

| Momentum | −0.193241*** | −0.139185*** | −0.114277** | |

| (0.051924) | (0.05094) | (0.051701) | ||

| IdioRisk | 1.32495** | −0.095393 | −0.600836 | |

| (0.536957) | (0.602949) | (0.618854) | ||

| SMB | −0.057086* | −0.06402** | −0.060965** | |

| (0.029348) | (0.029143) | (0.028882) | ||

| HML | −0.05821** | −0.033469 | −0.023308 | |

| (0.027546) | (0.028365) | (0.028334) | ||

| MOM | 0.063067 | 0.049764 | 0.04393 | |

| (0.039497) | (0.041231) | (0.040896) | ||

| MKTRF | −0.011837 | −0.019473 | −0.021195 | |

| (0.037811) | (0.037528) | (0.037246) | ||

| Cash | 0.11715 | 0.025652 | ||

| (0.182886) | (0.185154) | |||

| LTDebt | 0.203882* | 0.153615 | ||

| (0.116455) | (0.119014) | |||

| STDebt | 0.089888 | 0.05584 | ||

| (0.372684) | (0.369595) | |||

| ROA | −0.184574 | −0.070218 | ||

| (0.350769) | (0.355759) | |||

| Loss | 0.137836** | 0.138739** | ||

| (0.066743) | (0.0668) | |||

| InvTurn | −0.009037 | −0.011332 | ||

| (0.014647) | (0.014322) | |||

| RD&SGAstock | 0.835353*** | 0.769731*** | ||

| (0.193368) | (0.196311) | |||

| AcqIntang | −0.095428 | −0.123101 | ||

| (0.091664) | (0.092597) | |||

| DivPayout | −0.034599** | −0.028883* | ||

| (0.014502) | (0.014764) | |||

| ICweakness | 0.037994 | 0.039245 | ||

| (0.033308) | (0.033409) | |||

| MeanAnnSpeed | 0.410725 | 0.842382 | ||

| (0.914052) | (0.928586) | |||

| Size | −0.002498 | −0.037836 | ||

| (0.017385) | (0.027441) | |||

| Analyst | 0.007203** | |||

| (0.00354) | ||||

| MktShare | 0.092442 | |||

| (0.248538) | ||||

| Age | −0.011371*** | |||

| (0.003496) | ||||

| Age2 | 0.000123*** | |||

| (0.000041) | ||||

| InvestorOrient | 0.001387 | |||

| (0.002458) | ||||

| InstOwners | −0.000626 | |||

| (0.000852) | ||||

| lnCEOtenure | −0.004942 | |||

| (0.007496) | ||||

| _cons | −0.130439** | −0.239136*** | −0.222302 | 0.329132 |

| (0.05061) | (0.071826) | (0.223026) | (0.306005) | |

| Observations | 1642 | 1642 | 1642 | 1642 |

| R-squared | 0.071966 | 0.113659 | 0.152913 | 0.164847 |

| Industry Dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES |

- Note: Robust standard errors are in parentheses.

- ***p < .01,

- **p < .05,

- *p < .10.

Consistent with the much lower level of overall explanatory power, several variables that were important in explaining Q1 returns are no longer significant when considering returns for the entire year. For example, idiosyncratic risk, three out of the four Fama–French factors and inventory turnover are all insignificant in the full year returns regressions. Offsetting the loss in explanatory power of these variables, dividend payout and firm age both become negatively associated with returns in the full year model, whereas the loss indicator becomes positively significant.

Interestingly, long-term debt is largely insignificant in explaining full year returns (versus negatively significant in Q1), while cash and short-term debt are insignificant (versus positively and negatively significant for Q1, respectively, which was in line with expectations). These full- year results for the liquidity and debt variables, which are both counter-intuitive and inconsistent with the findings in prior GFC period studies and with those reported in the previous section for the Q1 COVID crisis period, may perhaps be explained by government interventions that began in the second quarter of 2020 and that continued in various forms through to the end of the year (i.e., traditional measures of financial structure vulnerability are no longer relevant when the government effectively steps in as a sponsor or guarantor). As leverage and liquidity are primarily control variables in our study, we leave it to future research to explain why their signs and significance differ from expectations over the longer period of the COVID pandemic.

The results in columns (3) and (4) indicate that investments in internally generated intangibles, captured by RD&SGAstock, remain significantly positive determinants of COVID full-year returns. Using the coefficient estimate from column (4), we find that a one-standard deviation increase in RD&SGAstock results in an economically significant 9.3% increase in full year abnormal returns (0.769731 * 0.12033202 ≈ 9.3%, again calculated using the industry- orthogonalized standard deviation of RD&SGAstock for the full year sample) even after controlling for industry fixed effects.

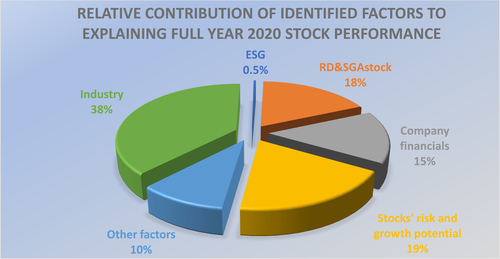

In order to understand the importance of each set of variables in explaining market returns for the full year period, we once again undertake an Owen-Shapley decomposition of the 16.5% explained variation in share price changes. Figure 2 presents the results of this analysis, with the findings indicating that there are some notable changes in the roles of different sets of variables in explaining the Q1 versus full year returns. Specifically, market-based risk proxies capture just 19% of the explained variation in annual returns, versus nearly 40% in Q1. Industry indicators are the most important set of variables in explaining full year returns, capturing 38% of the explained variation (versus an almost equivalent 34% in Q1). The explanatory power of the accounting variables, led by the importance of RD&SGAstock, increases dramatically in the full year returns to capture 33% of the explained variation (versus 20% in Q1). Of this 33%, more than half (i.e., 18%) is due to the internally generated intangible asset variable. The collection of other non-accounting/non-market variables are also more important in explaining annual versus Q1 returns, capturing 10% versus 4% of explained variation in each respective period. Finally, ESG remains a relatively useless variable, capturing less than 0.5% of the explained variation in returns for the full year returns period, similar to its irrelevance in the Q1 returns regressions.

Owen–Shapley R2 decomposition analysis full year 2020.

Notes: The pie chart in this figure represents the contribution of ESG, RD&SGAstock, company financials, stocks’ risk and growth potential, industry, and other factors to our full year 2020 model R2 (Table 5). Company financials consists of: Cash, LTDebt, STDebt, ROA, Loss, InvTurn, AcqIntang, DivPayout, ICWeakness, MeanAnnSpeed, Size, and RD&SGAstock, although we break out the latter variable separately. Stocks’ risk and growth potential consists of: BTM, BTMNeg, Momentum, IdioRisk, MKTRF, HML, SMB, and MOM. Other factors consist of: Analyst, Mktshare, Age, InvestorOrient, InstOwners, and lnCEOtenure. All percentages are rounded to the nearest integer [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Overall, the combined results from our analyses present a clear and consistent picture related to ESG as a potential resilience factor during the global pandemic. Specifically, in contrast to previous studies’ findings of a positive association between CSR and returns during the GFC period, and to the conventional wisdom during the recent crisis, ESG is not significantly associated with returns during the COVID pandemic. This finding is consistent across each of the Q1 market implosion and full COVID year of 2020 periods. By contrast, an accounting-based measure of firms’ investments in internally developed intangible assets is positively associated with returns for both periods, and its association is both statistically and highly economically significant. Our analyses do not address whether ESG is insignificant due to Refinitiv's score being a noisy measure of CSR performance versus whether the insignificance is due to a lack of economic relation between returns and the true underlying construct of interest. The specification checks in the next section explain this issue.

4.3 Specification checks

In this section, we report the results from a series of s29pecification checks using alternative measures for each of the returns dependent variable, as well as our ESG test variable of interest. For each specification check, we use the fully specified regression depicted in Model 1 with all variables included, but for the sake of parsimony we present only the coefficients on the ESG and RD&SGAstock variables of the interest.24

In the first two columns of Table 6, we report the results for each of the fully specified Q1 and full year regressions using raw returns as the dependent variable. In columns (3) and (4), we use the natural log of (1+BHAR) as the dependent variable.25 As shown, across all columns ESG remains insignificant, while RD&SGAstock remains economically and statistically significantly positively associated with returns. The results in Table 6 thus confirm that our key inferences are robust to alternative measures of returns.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RawReturn Q1 | RawReturn 2020 | ln(1+BHAR) Q1 | ln(1+BHAR) 2020 | |

| ESG | 0.000116 | −0.001277 | 0.000493 | 0.000097 |

| (0.000349) | (0.000999) | (0.000393) | (0.001301) | |

| RD&SGAstock | 0.109106* | 0.524703*** | 0.124635** | 0.861061*** |

| (0.057802) | (0.193151) | (0.063397) | (0.262191) | |

| _cons | −0.149981 | −0.108551 | −0.070824 | 0.825895** |

| (0.09729) | (0.27727) | (0.102977) | (0.348651) | |

| Observations | 1652 | 1642 | 1652 | 1642 |

| R-squared | 0.423143 | 0.216345 | 0.440198 | 0.189447 |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry Dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES |

- Note: Robust standard errors are in parentheses.

- ***p < .01,

- **p < .05,

- *p < .10.

In Table 7, we report the results of specification checks that focus more on the ES or corporate social responsibility (CSR), dimensions of ESG, leaving out the “G”, or governance element. In the first two columns, we report the results of fully-specified Q1 and full year BHAR regressions using MSCI data to capture CSR. Specifically, we follow Lins et al. (2017) to construct an ESG_MSCI variable by first dividing the number of strengths (concerns) for each of five categories of performance (community, human rights, diversity, employee relations and environment) by the maximum possible number of strengths (concerns) in that category. We then construct a net ESG measure for each category by subtracting the scaled number of strengths from the scaled number of concerns, and finally we sum the net measures across categories to obtain the ESG_MSCI summary score. As shown in the table, ESG_MSCI is insignificant in explaining COVID Q1 crisis and full year 2020 returns, while RD&SGAstock remains economically and statistically significant.26

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BHAR Q1 | BHAR 2020 | BHAR Q1 | BHAR 2020 | |

| ESG_MSCI | 0.013309 | 0.01077 | ||

| (0.008795) | (0.024215) | |||

| ES | 0.000413 | 0.0006 | ||

| (0.000303) | (0.000939) | |||

| RD&SGAstock | 0.124033** | 0.534962*** | 0.139449** | 0.7644*** |

| (0.059792) | (0.171475) | (0.057545) | (0.196903) | |

| _cons | −0.18614** | 0.289562 | −0.041449 | 0.330554 |

| (0.078425) | (0.235481) | (0.102969) | (0.306927) | |

| Observations | 1606 | 1596 | 1652 | 1642 |

| R-squared | 0.421903 | 0.176742 | 0.421198 | 0.165023 |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry Dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES |

- Note: Robust standard errors are in parentheses.

- ***p < .01,

- **p < .05.

In the last two columns of Table 7, we use just the ES component of Refinitiv's ESG as the test variable of interest (ES).27 As shown, ES is insignificant in explaining returns for both periods, while the prior inferences related to RD&SGAstock are unaffected. We conclude from the results in Table 7 that our inferences regarding the insignificance of ESG are robust to measures of just the environmental and social components (ES) of CSR.

In Panel A of Table 8, we report the results of fully-specified Q1 and full year BHAR regressions using what we refer to as the Refinitiv II dataset to capture ESG. In April 2020, Refinitiv restated previously reported ESG measures, and Berg et al. (2021) have noted that these changes are systematic and related to past performance, suggesting that depending upon whether the original Refinitiv versus Refinitiv II rewritten data are used, the observed relation between ESG and returns may be different. As shown in Panel A of Table 8, however, even using the restated Refinitiv II data, ESG_ReftvII is not significantly associated with returns in either Q1 or for the full year of 2020.

| Panel A: Refinitiv II | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| BHAR Q1 | BHAR 2020 | |

| ESG_ReftvII | 0.000308 | 0.001148 |

| (0.000319) | (0.000999) | |

| RD&SGAstock | 0.16146*** | 0.695191*** |

| (0.059332) | (0.194067) | |

| _cons | −0.025576 | 0.547707* |

| (0.095297) | (0.282994) | |

| Observations | 1694 | 1686 |

| R-squared | 0.421148 | 0.18248 |

| Controls | YES | YES |

| Industry Dummies | YES | YES |

| Panel B: ESG Top performers | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| BHAR Q1 | BHAR 2020 | |

| ESG_top | −0.001294 | −0.017714 |

| (0.015517) | (0.034123) | |

| RD&SGAstock | 0.14376** | 0.773575*** |

| (0.057558) | (0.195624) | |

| _cons | −0.043192 | 0.32379 |

| (0.101796) | (0.306011) | |

| Observations | 1652 | 1642 |

| R-squared | 0.420587 | 0.164886 |

| Controls | YES | YES |

| Industry Dummies | YES | YES |

- Note: Robust standard errors are in parentheses.

- ***p < .01,

- **p < .05,

- *p < .10.

In our last specification check, we consider the potential impact that “greenwashing” may have on our reported results. It is conceivable that firms that are greenwashing may benefit from enhanced ESG scores (i.e., that the ratings purveyor does not adequately “see through” this window dressing). In other words, it is plausible that ESG scores are “noisy”, especially through the middle of the distribution, in discriminating between firms with moderately low, moderate, or moderately high actual (i.e., as opposed to measured) environmentally and socially responsible behavior, whereas the theory suggests that it is the actual behavior that should lead to resilience in times of crisis. Under the assumption that firms that are mainly greenwashing would not attain a very top ESG score, we create a relatively greenwashing-free measure of ESG performance by setting an indicator variable, ESG_top, equal to one for firms in the top decile of our sample on the basis of their original Refinitiv ESG scores and setting it to zero otherwise.28 Panel B of Table 8 reports Q1 and full year regressions using this indicator variable to capture ESG performance. As shown, for both periods ESG_top is insignificant, while our inferences related to RD&SGAstock remain unchanged. In other words, these results indicate that the stock returns of even the highest performing ESG firms, which are those that are most likely to be truly performing well on ESG rather than merely gaming the ratings, were not higher during the Q1 2020 market implosion, nor for the full COVID year, after controlling for other standard determinants of returns.

In summary, the specification checks in this section confirm that our results are robust to alternative measures of stock returns and to numerous alternative measures of ES and ESG performance. Specifically, our results consistently indicate that ESG is not a significant explanatory variable for returns for the Q1 crisis period, nor for the returns of the full COVID year of 2020. Furthermore, RD&SGAstock remains a positively and statistically significant variable in explaining returns across all specifications. The combined results strongly support the conclusion that ESG is not a share price vaccine during the COVID pandemic, but that investments in internally generated intangible assets are an economically significant resilience factor during the current global crisis. While we cannot definitively rule out that the numerous ESG measures derived from three different databases all provide such poor proxies for CSR performance that this noisy measurement is causing the insignificance across all specifications, we consider it to be more likely that the global insignificance is due to a lack of robust economic relation between generic, summary level ESG (or ES) performance and stock returns during the COVID crisis.

5 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

Despite the dramatic increase in responsible investing in recent years, and especially during the COVID-19 crisis in 2020, the question as to whether ESG pays off for shareholders (i.e., whether doing good is good for investors – remains the subject of considerable debate (see, e.g., Matos, 2020, versus Whelan et al., 2021). Proponents of corporate social responsibility claim that it is particularly valuable as a risk mitigation strategy, offering the prospect of significant downside protection in the periods of crisis. Consistent with this, ESG-tilted fund managers, ESG data purveyors, as well as financial journalists, have all been trumpeting the value of ESG as a share price “vaccine” during the current COVID pandemic. Contrary to these widespread claims, however, the extensive analyses presented in this study present robust evidence that neither ESG nor ES was a share price resilience factor during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study therefore calls into question the generalizability of GFC period findings that CSR is a resilience factor in times of crisis.

While our results do not explain the longer-term shareholder value creation of responsible corporate citizenship, an approach to doing business that we support and advocate for, they do establish that firms with higher ESG scores did not experience superior returns either during the pandemic-induced selloff in the first quarter of 2020 or for the full COVID 2020 year, once industry affiliation and accounting- and market-based determinants of returns have been properly controlled for. By contrast, the firm's stock of investments in internally-generated intangible assets is highly economically significant in explaining returns during each of the Q1 2020 market crisis and full year 2020 periods, suggesting that the flexibility that derives from a large stock of innovative assets is more important than the firm's social capital to share price resilience during this global pandemic. Overall, we conclude that ESG did not immunize stocks during the COVID-19 crisis, but that investments in intangible assets did.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We appreciate the research assistance of Daniyal Ahmed, as well as comments from Eli Amir, John Hand, Kevin McMeeking, and workshop and conference participants at the Tilburg University, NYU, IESEG, the Sorbonne Alliance, Brunel Business School, Vlerick Business School, Tel Aviv University, the 44th ANPAD Conference in Brazil, the Canadian Sustainable Finance Network and the Egypt Online Seminars in Business, Accounting and Economics. Funding for this work was provided by the University of Waterloo's School of Accounting & Finance Research Grant program (Demers), and a CentER scholarship from Tilburg School of Economics and Management (Hendrikse). These funding sources have had no role in the preparation of this manuscript.

APPENDIX

Variable Definitions

| AcqIntang | Compustat items (GDWL + INTANO)/adjAT. Goodwill and other intangibles set to zero if missing. |

| Age | Years of data available before 2020 in Compustat annual. |

| Analyst | I/B/E/S item NUMEST. Set to zero if missing. |

| BHAR | Abnormal buy-and-hold returns calculated as in accordance with Barber and Lyon (1997). We use the market model, CRSP value-weighted, and a 60-month estimation window to calculate expected returns, requiring at least 12 months of returndata to be available. |

| BTM | Compustat items CEQ / (PRCC_C * CSHO). |

| BTMneg | Indicator set to one if BTM is negative. |

| Cash | Cash and short-term investments scaled by total assets. Compustat items CHE / adjAT. |

| DivPayout | Dividend payout ratio defined as dividends / net income. Compustat items DV/NI. Set to zero if missing. |

| ES | Refinitiv EIKON 0.5*EnvironmentPillarScore + 0.5* Social Pillar Score for FY2018. |

| ESG | Refinitiv EIKON ESG Score for FY2018. |

| ESG_MSCI | Using 2018 MSCI ESG Stats data, we follow Lins et al. (2017) in considering the categories community, human rights, diversity, employee relations and environment. We divide the number of strengths (concerns) for each category by the maximum possible number of strengths (concerns) in that category. We then subtract the scaled number of strengths from the scaled number of concerns and sum the net measures across categories to obtain ESG_MSCI. Missing strengths are set to zero. |

| ESG_ReftvII | Refinitiv EIKON rewritten ESGScore for FY2018. |

| ESG_top | A dummy variable taking the value of 1 if a firm's ESG score is in the top decile of the original Refinitiv ESG Score distribution. |

| HML | Loading on Fama–French's high minus low factor. |