Researching belonging in the context of research with people with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review of inclusive approaches

Abstract

Background

In disability studies belonging is emerging as a promising area of study. Inclusive research, based as it is on lived experience perspectives, is likely to provide salient insights into belonging in the lives of people with intellectual disabilities.

Method

A systematic review utilising four databases and five leading journals in the field of intellectual disabilities was used. Content analysis and a deductive synthesis of the extracted data was undertaken.

Results

A high level of confluence was found between the findings of the included studies and key themes of belonging identified in the wider literature. Beyond this, studies utilising inclusive research approaches have contributed novel findings about belonging in the lives of people with intellectual disabilities.

Conclusions

Inclusive research approaches to belonging may provide innovative and responsive frameworks to support people to develop a sense of being connected and “at home” in themselves and in their communities.

1 INTRODUCTION

Social inclusion remains a key policy objective in relation to the lives of people with intellectual disabilities. Despite overarching policy ambitions, social inclusion is generally narrowly defined in relation to community access and workforce participation (Simplican et al., 2015). However, it has been suggested that social inclusion discourses underrepresent the lived experience perspectives of people with intellectual disabilities themselves (Overmars-Marx et al., 2014). This is despite the preamble to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) (2006) articulating the right to both social inclusion and a sense of belonging for people with disabilities. As the concept of social inclusion has become increasingly contested and politicised, there has been a corresponding research focus on the meaning and implications of belonging in the lives of people with intellectual disabilities (Nind & Strnadová, 2020). In disability studies, belonging is an emerging concept which extends understandings of social inclusion, to a focus on understanding the subjective experience of social inclusion from the perspective of people with intellectual disabilities themselves (Renwick et al., 2019; Robinson et al., 2020).

Concurrently, inclusive research approaches have emerged and developed, particularly in the intellectual disabilities field (Jones et al., 2020). The term “inclusive research” was coined by Walmsley (2001) to describe a unique collaborative approach to research between academic researchers and co-researchers with intellectual disabilities. Inclusive research generally incorporates a range of methods which may also be labelled as participatory, action or emancipatory research (for a full discussion, see Bigby et al., 2014; Nind & Vinha, 2012; Nind, 2014; Walmsley & Johnson, 2003; Walmsley et al., 2018). These approaches are united in their respective attempts to democratise some or all phases of the research process through increasing collaboration with researchers with intellectual disabilities (Nind, 2014).

Belonging has been acknowledged as a central concern in inclusive research, both in that research about belonging is best served by inclusive approaches and that belonging is itself key to the process of undertaking inclusive research. Walmsley et al. (2018) propose that inclusive research is “research that aims to contribute to social change, that helps to create a society in which excluded groups belong [emphasis added], and which aims to improve the quality of their lives” (p. 758). It has been argued that a focus on the experience of people on the margins challenges the normative construction and majority control of belonging (Mee & Wright, 2009). Inclusive research studies of belonging can make a valuable contribution to challenging normativity and majority control and enable novel and progressive perspectives on the social inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities. In addition, inclusive research approaches to belonging are important because they value and provide access to underrepresented insights and perspectives of people with intellectual disabilities and contribute to the expansion of a bottom-up, lived-experience informed understanding of social inclusion.

Inclusive research approaches in intellectual disabilities have advanced methodological theory and practice in the field (Jones et al., 2020). A systematic review of studies of belonging and reciprocity for people with intellectual disabilities identified the promise of inclusive data collection methods to the study of belonging (Fulton et al., 2021), arguing that they were useful for garnering an in-depth understanding of participants' subjective experiences of belonging which may not have been possible using semi-structured interviews alone.

The systematic review presented in this manuscript sought to investigate this promise further and consider the contribution of inclusive research approaches to understanding the enablers of belonging. The focus of this review allowed for the capture of a range of inclusive data collection methods used in research on belonging and in particular, for mapping collaboration with researchers with intellectual disabilities at different phases of the research. It is the first review to systematically assess inclusive empirical studies of belonging. The review fills a research gap by connecting belonging as an explanatory concept with the study of belonging as an inclusive research topic. We contend that understanding the enablers of a sense of belonging in the lives of people with intellectual disabilities via inclusive research approaches can enhance knowledge and enrich social inclusion discourses.

The following sections explore the value of belonging to understanding the social inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities, describes the challenge of operationalising inclusive research approaches and outline the strategy used in this review to map collaboration across the included studies.

1.1 The importance of belonging to social inclusion

The authors acknowledge the broad interdisciplinary scholarship on belonging that has informed its development and use in disability studies. Of particular significance are the works of Yuval-Davis (2006; 2011) and Antonsich (2010), which suggest that any conceptual framework of belonging needs to differentiate between two different modes of belonging; a subjective sense or experience of belonging and a politics of belonging. Disability scholars have argued that the concept of a sense of belonging might facilitate a qualitatively different mode of engagement with people with intellectual disabilities in relation to social inclusion (Strnadová et al., 2018). It has been argued that definitions of social inclusion can overlook what is important to living a good life and experiencing a sense of belonging (Cummins & Lau, 2003; Johnson & Walmsley, 2010; Simplican et al., 2015). Therefore, some scholars have argued for a focus on subjective measures of social inclusion, related to the degree that a sense of belonging is felt by people with disability themselves (Cobigo et al., 2012).

Some commonality in concepts has been identified across the belonging literature, including that belonging is a deeply felt human need, is multidimensional and highly subjective in nature, and that belonging has been under-utilised and under-researched (Strnadová et al., 2018). Strnadová et al. (2018) developed five key interconnected themes from the research literature on belonging which are less abstract than those previously suggested in the literature (see Mahar et al., 2013), and therefore more readily operationalised. The themes identified were: (i) positioned belonging, which relates to the cultural context into which we are born, (ii) belonging as identity, which relates to the formation of individual identities through the interaction of memory, place, history and the extent to which people feel at home in themselves, (iii) belonging as relational, which they argue is generally agreed to be a central characteristic of belonging, (iv) belonging in relation to place, which refers to the importance of relationship to place as an indicator of the degree of belonging people feel, at local, regional and national levels, and (v) belonging as a contributor to society, which relates to the extent to which people with intellectual disabilities have opportunities to make a contribution, including beyond participation in the labour market. These five themes are used in the study presented in this paper to map the findings of the studies included in its systematic review.

1.2 Operationalising inclusive research approaches to belonging

Belonging is a topic of interest to inclusive researchers to explore and understand the embodied and subjective experience of a sense of belonging for and from the perspective of people with intellectual disabilities themselves. Inclusive research approaches present an opportunity to magnify the voices of researchers and participants with intellectual disabilities and to potentially provide novel insights into the manifestation of well-intentioned social inclusion policy being experienced as social exclusion (Power, 2013). What is experienced as social inclusion by one person with intellectual disabilities may not be similarly experienced by a different person with intellectual disabilities (Power & Bartlett, 2018), and inclusive research approaches offer an opportunity to unpack these experiences from a lived experience or insider perspective that would not otherwise be accessible to academic researchers.

Early formative work by Walmsley and Johnson (2003) suggests that the operational potential of inclusive research is that people with intellectual disabilities might be “initiators, doers, writers and disseminators of research” (p. 9). More recently the contribution of researchers with intellectual disabilities in inclusive research, the social change imperative of such research and the centrality of collaboration has been emphasised (Walmsley et al., 2018). Inclusive research approaches are united axiologically, in that they are driven by values and ethics. Put simply, it is now widely agreed that it is necessary to include people with intellectual disabilities in research about them and that epistemologically, collaboration with researchers with the lived experience of being a person with an intellectual disabilities label is the preferred paradigm (Nind, 2014).

The principles and purposes of inclusive research have been well defined; however, the parameters of its operationalisation are less clear. There is a noted tension and lack of clarity in inclusive research approaches between intention and operationalisation or its stated and enacted dimensions (Jones et al., 2020). Inclusive research approaches have been described as encapsulating a continuum of involvement (Bigby et al., 2014). One way of operationalising inclusive research can be identified through methods associated with co-production. Co-production is founded in collective decision making and aims to democratise traditional research relations between users and producers (Strnadová et al., 2022). It refers to the collaborative process of academic researchers and people with disability undertaking research together. Axiologically, co-production is consistent with the broad umbrella of inclusive research approaches concerned with democratising the research process (Nind, 2014). In co-production, people with intellectual disabilities are involved as part of the research team as advisors or as co-researchers (Strnadová et al., 2022).

Drawing on current literature and practice approaches, Strnadová et al. (2022), have usefully mapped co-production to the typical phases of research in order to provide guidance to academic and community researchers interested to operationalise their inclusive practice in disability research. This co-production model allows for a more accurate mapping of collaboration across the research process and includes six phases, (i) initiating, (ii) planning, (iii) doing, (iv) sense making, (v) sharing, and (vi) reflecting (Strnadová et al., 2022). The study presented in this paper utilises the phases of co-production model (Strnadová et al., 2022) to map self-reported collaboration across the phases of studies included in its systematic review. The characteristics of each phase can be seen in Table 1.

| Phases | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| 1. Initiating | This phase relates to how the research focus of the project is generated |

| 2. Planning | This phase is focused on the design of the project and how co-production will occur |

| 3. Doing | In this phase activities related to ethics, recruitment and data collection are undertaken |

| 4. Sense making | The focus of this phase is on collaborative data analysis |

| 5. Sharing | This phase is about the collaborative means of disseminating research findings |

| 6. Reflecting | In this phase the research team collaboratively considers the research process undertaken and the implications for future projects |

While this approach may not resolve the tension between intention and enactment, it provides for visibility and transparency of collaboration across the life of research projects. The use of the co-production model in this paper aims to achieve a more confident assessment of claims about inclusivity in research projects rather than to assess the level or quality of that involvement.

1.3 Aims and research questions

The aim of this review is to better understand the contribution of inclusive research approaches to the study of belonging. There are two research questions guiding this review: (1) What are the characteristics of inclusive research approaches to belonging and how are they operationalised? (2) What does inclusively produced research tell us about belonging in the lives of people with intellectual disabilities?

2 METHOD

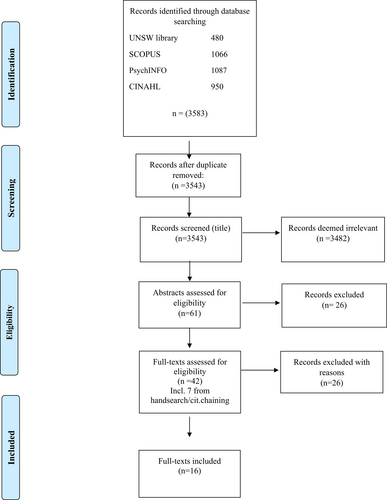

In order to comprehensively assess current knowledge about inclusive research approaches to belonging, systematic review was identified as the appropriate review method. For the purposes of this research a systematic review methodology has the advantages of: (1) clearly formulated research questions; (2) systematic, transparent and replicable methods to identify the data set (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [Moher et al., 2009]); and (3) a validated instrument to critically assess the quality of the included articles (Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields [Kmet et al., 2004]). Further, researcher triangulation involving at least two of the authors analysing and interpreting the data, was used at each phase of the systematic review process (Campbell et al., 2020).

The review was conducted in line with the recommendations for systematic reviews outlined in the PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., 2009) as detailed in Figure 1. The QualSys tool (Kmet et al., 2004) was used to assess the quality of the included articles. The tool assesses quality across all stages of the reported study, functions with qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies and importantly, given the focus of the current review, assesses researcher reflexivity. Given the inherently relational and collaborative nature of inclusive research approaches, these criteria are critical to assessing the quality of the included articles.

This systematic literature review covers the period January 2000 to March 2022. Initial searches suggested that relevant studies were concentrated in this period where there has been an increased focus on belonging as a research topic in disability studies and a concurrent intensification of conceptual debates about the definition/s of inclusive research (Bigby et al., 2014; Nind, 2014; Walmsley et al., 2018; Walmsley & Johnson, 2003). The period has also seen growing research interest in the stages/phases of inclusive research approaches (Chapman & McNulty, 2004; Dias et al., 2012), the role of co-researchers with intellectual disabilities (Frankena et al., 2015; Frankena et al., 2018) and the position and value of inclusive approaches in broader academic research (Walmsley et al., 2018).

2.1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included, articles needed to meet all of the following criteria: (a) be written in English and published in a peer-reviewed journal; (b) be published between 2000 and 2022; (c) include social inclusion and/or belonging in either aim, research questions or findings; (d) have people with intellectual disabilities as part of the research team; and (e) draw on empirical data including the perspectives of people with intellectual disabilities. Articles were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (a) focused on disabilities other than intellectual disabilities; (b) focused on the perspective of stakeholders other than people with intellectual disabilities (for example, family members and service providers); (c) were not directly reporting on original empirical research; (d) were solely methodological and/or theoretical. After initially being included, articles that provided secondary analysis of inclusive studies but were not themselves conducted inclusively were excluded at the full-text cull phase.

2.2 Search strategy

The databases searched included PsychINFO, CINAHL, Scopus, and a university library. Hand searches in five leading journals were also conducted (Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disability, Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, Disability and Society, and British Journal of Learning Disability). Searches were conducted between September 2020 and March 2022.

Title, keyword, and abstracts were the search categories used. Complete and truncated versions of the following search terms were used: belonging, social inclusion, acceptance, participation, social exclusion, integration, citizenship, community participation, connection, relationships, quality of life, intellectual disabilities, learning disabilities, learning difficulties, developmental disabilities, cognitive disabilities, cognitive impairment, mental retardation, mental handicap, developmental delay, inclusive research, inclusive design, inclusive approaches, participatory, co-researchers, collaborative, emancipatory, transformative, co-design, co-production.

2.3 Search results

Electronic database searches yielded a total of 3583 articles, including 40 duplicates. Of these, 3482 articles did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining 61 abstracts were screened independently by the first and second author and a further 26 were excluded. Cohen's kappa assessment of inter-rater reliability demonstrated a high-level score for this phase (89%) (Cohen, 1960; McHugh, 2012). The first and second authors independently completed a full-text assessment of the remaining 42 articles and again achieved a high level of inter-rater reliability (95%). Disagreements were discussed and resolved by all authors. A final set of 17 articles met the inclusion criteria at this stage.

2.4 Data extraction and quality assessment

Purpose designed pro-forma analytic sheets were developed by the first and second author. The analytic sheets were completed as a means of compiling a detailed summary of each of the included articles. They included the research questions, details about the inclusive approach described and an overview of the findings specifically related to belonging. Data extraction was completed by the first author and verified by the second author. Summary information on the included articles is contained in Table 2.

| Authors (year), country | Participants (sample size) | Objective | Methods | Key findings related to social inclusion and/or belonging | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milner and Kelly (2009), New Zealand | 28 vocational disability service users with a range of sensory, intellectual, and physical disabilities; aged 25–56; 17 men and 11 women | To develop shared understandings of community participation in the lives of vocational service users | Interviews, focus groups and self-authored life story; thematic analysis | Five key antecedents to a sense of community belonging were identified: self-determination, social identity, reciprocity and valued contribution, participatory expectations, and psychological safety. | Moderate: 70% |

| Dias et al. (2012), United Kingdom | 8 older people with intellectual disabilities; age and gender not provided | To record the memories of the Second World War and examine the emancipatory research process used | Oral history interviews, observation, and photography; thematic analysis | Desire to be part of the wider society. However, experiences of inclusion and experiencing a sense of belonging are generally in segregated groups. | Strong: 80% |

| Koenig (2012), Austria | 40 people with intellectual disabilities; aged 25–45; 20 men and 20 women | To examine experiences of participation | Mixed method: interviews, survey; grounded theory | The challenge of knowing which “camp” they belong to was identified. In response to these challenges some participants, faced with their own intellectual disabilities' identity, distanced themselves from other people with intellectual disabilities. | Strong: 90% |

| Haigh et al. (2013), United Kingdom | 20 people with intellectual disabilities; aged 23–67; 52% were men and 48% women | To find out what makes people happy with their lives | Mixed methods: interviews, questionnaire; thematic analysis of interviews | Key components reported as contributing to feeling happy and satisfied with life included relationships, choice and independence, activities, and valuable social roles. | Strong: 100% |

| García Iriarte et al. (2014), Ireland | 168 adults with intellectual disabilities; aged 18-over 50; 83 men and 82 women | To define key concerns about participation in society | Focus groups; grounded theory strategy and thematic content analysis | Taking part in activities in the local community was reported as creating a sense of belonging. Antecedents to belonging and not belonging included, choice and control, and was impacted by feeling included or excluded from society. | Strong: 80% |

| Frawley and Bigby (2015), Australia | 12 self-advocates; all but 1 aged over 55; gender not provided | To identify what membership of a self-advocacy group means and how it affects social inclusion | Group interviews; general inductive approach | Membership of self-advocacy group was linked to a sense of belonging, social connections, and doing things that matter. Membership of self-advocacy groups was found to be a mechanism for social inclusion. | Strong: 90% |

| Heffron et al. (2018), United States | 146 adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities; aged 30 or older; 84 men and 61 women | To evaluate Photovoice as a participatory method, to examine barriers to community participation, and suggest strategies to improve self-determination and community participation | Photovoice; thematic analysis | Supports and barriers to community participation include physical, social, and economic environments and community participation. | Strong: 85% |

| Wilton et al. (2018), Canada | 12 adults with intellectual disabilities; aged from early 20's to late 50's; 8 men and 4 women | To understand how public spaces like shopping centres are use and given meaning. | Interviews and participant led go-along interviews; thematic analysis | The significance of place to social inclusion and a sense of belonging for people with intellectual disabilities was identified. Shopping and consumption in particular places were related to experiencing a sense of belonging but could be negatively affected by the reactions of others sharing those spaces. | Strong: 90% |

| Mooney et al. (2019) United Kingdom | 8 people with intellectual disabilities who are members of an inclusive research group; age and gender not provided | To identify barriers to increased involvement at community venues, in community activities and in friendships | Discussion groups; thematic analysis | Practical barriers were more common than unwelcoming communities in relation to community involvement. | Moderate: 75% |

| Renwick et al. (2019), Canada | 24 Young people with intellectual and developmental disabilities; aged 13–24; 9 female and 15 male | To learn about young people's experiences of friendship, community participation, and quality of life in the transition to adulthood | Video-recorded interviews; Constructivist grounded theory | Belonging and not belonging are important in the transition to adulthood. A belonging framework with four dimensions was developed: interacting with similar people, negotiating meaningful roles in the community, engaging in social relationships and, finding a good fit. | Strong: 90% |

| Robinson et al. (2020), Australia | 30 young people with intellectual disabilities; aged 12–25; gender not provided | To explore belonging and exclusion from the perspective of young people with intellectual disabilities | Pictorial mapping and Photovoice; thematic analysis | Sense of belonging for participants was positively impacted by being valued and recognised, feeling comfort and safety in relation to people and places, relationships and positive connections with family, friends, and support workers. Not belonging was related to negative perceptions related to participants' intellectual disabilities | Strong: 80% |

| Rojas-Pernia et al. (2020), Spain | 23 young people with and without intellectual disabilities; age and gender not provided | To investigate the importance of social relationships and loneliness | Interviews and body mapping; thematic analysis | For young people with and without intellectual disabilities relationships are important to reduce loneliness, and mobile phones increase social isolation and loneliness rather than enhance it. People with intellectual disabilities want to feel part of something and social change is needed to achieve inclusion. | Moderate: 70% |

| Witsø & Hauger, 2020, Norway | 9 adults with intellectual disabilities; aged 22–58; 3 men and 6 women | To explore the experience of everyday life and its challenges | Workshops, inductive thematic analysis | Belonging to a family, friendship, and leisure activities was found to be important in people's lives. However, they desired more social and community participation and more respect from staff. | Moderate: 75% |

| Martin et al. (2021), Australia | 114 adults with intellectual disabilities; mean age was 41.88; 46% were women and 54% male | To investigate how the use of mobile technology can enhance social inclusion | Survey, multivariate path analysis | Use of mobile technology was positively associated with social inclusion in relation to family, friends work and volunteering. | Strong: 95% |

| Kaley et al. (2021), United Kingdom | 43 adults with intellectual disabilities; aged 18–70; 24 men and 19 women | To examine how people with a sense of belonging is created through co-constructing local networks of support | Interviews, focus groups, observation and activities, photo voice; participatory thematic analysis | Self-advocacy groups and local friendship groups offered an important source of belonging. Spending time with family, friends and being an active member of the community also facilitated a sense of belonging. | Strong: 95% |

| Power and Bartlett (2018), United Kingdom | 4 adults with intellectual disabilities; aged 40–55; 3 men and 1 woman | To explore what it means to live in a ‘welcoming community’ in a context of personalisation | Group interviews, photo diaries, photo-elicitation; thematic analysis | Six types of ‘safe havens’ were identified which fostered inclusion and belonging and included places which are: relational, for rest, of memory, democratic, of insider status and, spaces of incognito. Four examples of ‘self-building practices’ were used to describe how participants found and negotiated safe havens: dog walking, making home meaningful, friendship groups and gardening. | Moderate: 65% |

Articles were rated using the QualSYS tool (Kmet et al., 2004) and the percentage bracketing used by Eddens et al. (2018), with scores rated <55% as weak, 55%–75% as moderate and >75% as strong. Scoring was completed independently by the first two authors. Inter-rater reliability (Cohen, 1960; McHugh, 2012), was high (90%) and discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached. Overall, the quality of the articles was high, with 11 articles scored as strong, five as moderate and one as weak. Subsequently, the one article with the weak score was excluded as its score (25%) was deemed to be of insufficient quality to be included. The remaining 16 articles made up the final set for review.

2.5 Study characteristics

The majority of the included articles (13) reported on qualitative studies, two reported on mixed-method studies (Haigh et al., 2013; Koenig, 2012) and the remaining article (Martin et al., 2021) reported on the quantitative part of a mixed-method study. A total of 689 participants with intellectual and developmental disabilities were included across the studies. Studies were concentrated in English-speaking countries, United Kingdom (Dias et al., 2012; Haigh et al., 2013; Kaley et al., 2021; Mooney et al., 2019; Power & Bartlett, 2018), Ireland (García Iriarte et al., 2014), Canada (Renwick et al., 2019; Wilton et al., 2018), United States (Heffron et al., 2018), Australia (Frawley & Bigby, 2015; Martin et al., 2021; Robinson et al., 2020), New Zealand (Milner & Kelly, 2009). Only three studies were conducted in non-anglophone countries, Austria (Koenig, 2012), Norway (Witsø & Hauger, 2020), and Spain (Rojas-Pernia et al., 2020). This may reflect the searches being restricted to English language publications but arguably also reflects the origins and interest in inclusive research approaches in English speaking countries (particularly the United Kingdom) over the last two decades.

Some studies offered a choice of data collection instruments (Milner & Kelly, 2009), and seven used a range of qualitative data collection instruments to maximise the potential for participants to engage in meaningful ways, for example oral history interviews and photography (Dias et al., 2012) and pictorial mapping and photovoice (Robinson et al., 2020). None of the studies used only semi-structured interviews.

Thematic analysis was used in 12 of 16 studies. Constructivist grounded theory was used in two studies (Koenig, 2012; Renwick et al., 2019). One study utilised a mixed grounded theory strategy and thematic content analysis (García Iriarte et al., 2014), and a general inductive approach was used in one study (Frawley & Bigby, 2015). The one quantitative study in the sample used multivariate path analysis (Martin et al., 2021).

2.6 Data analysis

Inclusive research characteristics of the included articles were identified by three measures: (1) labels used to identify researchers with intellectual disabilities; (2) team composition; and (3) authorship (as detailed in Table 3). The inclusive characteristics of each study, as operationalised by co-production activities/phases were drawn from the Summary of included articles (Table 2) and the proforma data analysis sheets. Self-reported instances of co-production were compiled in table form using the six phases of co-production in inclusive research developed by Strnadová et al. (2022). A deductive synthesis of the extracted data (Tilley et al., 2020) was then undertaken using the five interconnected themes identified in the belonging literature (Strnadová et al., 2018). There were two phases to the deductive synthesis undertaken: (1) The summary of thematic findings information in Table 2 was mapped to the five themes identified by Strnadová et al. (2018) in the belonging literature, (2) The alignment of the findings to the themes was then checked against the analytic sheets as they contained a more detailed overview of each included study. Phases were undertaken sequentially, initially by the first author, then discussed and refined with the second author until agreement was reached.

| Study | Co-researcher label | Team compositiona | Authorship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Milner and Kelly (2009) | Research team | 6 researchers with disability and 2 academic researchers | Academics |

| Dias et al. (2012) | Researchers and Steering group | 1 co-researcher with intellectual disabilities (steering group numbers unspecified) and 1 academic | Co-authored (lead) |

| Koenig (2012) | Reference group | 12 people with intellectual disability and 1 academic | Academic |

| Haigh et al. (2013) | Researchers | 2 researchers with intellectual disabilities and 3 academic researchers | Co-authored |

| García Iriarte et al. (2014) | Co-researchers | 25 co-researchers and 4 academic researchers | Co-authored |

| Frawley and Bigby (2015) | Self-advocates/ group members | 12 self-advocates and 2 academics | Academics |

| Heffron et al. (2018) | Participants | 146 participants and 4 academics | Academics |

| Wilton et al. (2018) | Participants | 12 participants and 3 academics | Academics |

| Mooney et al. (2019) | Research group | 8 research group members and 1 academic | Co-authored (lead) |

| Renwick et al. (2019) | Project consultants | 3 project consultants and 6 academics | Academics |

| Robinson et al. (2020) | Consultants | Unspecified number of consultants and 4 academics | Academics |

| Rojas-Pernia et al. (2020) | Co-researchers | 8 co-researchers with intellectual disabilities and 2 academics | Co-authored (2 + 2) |

| Witsø and Hauger (2020) | Participants | 9 people with intellectual disabilities and 2 academics | Academics |

| Martin et al. (2021) | Chief Investigator and advisory group | 1 CI and 4 advisors with intellectual disabilities and 4 academics | Co-authored |

| Kaley et al. (2021) | Advisory group | Unspecified number of members in advisory group and | Co-authored |

| Power and Bartlett (2018) | Participants | 4 participants and 2 academics | Academics |

- a We have only included co-researchers and academics for the purposes of this review and no other stakeholders (for instance Witsø & Hauger, 2020 also involved two intellectual disability nurses).

3 FINDINGS

The following section reports on the findings from analysis conducted in the systematic review of selected studies. First, findings related to the characteristics and operationalisation of inclusive research approaches to belonging are detailed. Then, findings related to thematic insights into belonging emerging from the studies are presented, organised according to the five interconnected themes identified in the wider belonging literature.

3.1 Inclusive characteristics of included articles

A range of labels are used to designate the role of the researcher with intellectual disabilities across the 16 studies. Two of the articles reflected the collaborative dimension of co-production by not distinguishing between members of the research team with and without intellectual disabilities, using labels such as research team (Milner & Kelly, 2009) and research group (Mooney et al., 2019). All the other articles used labels which distinguished group members with and without intellectual disabilities (see Table 3). Three studies referred to researchers with intellectual disabilities as a group, reference group (Koenig, 2012), and advisory group (Kaley et al., 2021; Martin et al., 2021). The remainder of the articles used individual role designations for team members with intellectual disabilities; co-researchers (García Iriarte et al., 2014; Rojas-Pernia et al., 2020), consultants (Renwick et al., 2019; Robinson et al., 2020), self-advocates (Frawley & Bigby, 2015), and participants (Heffron et al., 2018; Power & Bartlett, 2018; Wilton et al., 2018; Witsø & Hauger, 2020). Despite their involvement being more than simply as respondents in the research, members of the research team with intellectual disabilities were referred to as participants in a quarter of the articles (four). Table 3 shows the labelling choices made in the articles.

A higher ratio of people with intellectual disabilities to academics is observed in studies using the term participants. However, this is not necessarily indicative of the level of co-production in the research but is rather more likely to reflect the type of inclusive approach adopted. For instance, Participatory Action Research (PAR) projects generally count all participants as ‘researchers.’ The notable exception is García Iriarte et al. (2014), who had 25 co-researchers involved in their study, five as part of the core research team and another 20 who conducted focus groups. Seven of the articles were co-authored by academic researchers and researchers with intellectual disabilities and two articles led by researchers with intellectual disabilities. Over half the articles (9) were authored by academics alone.

3.2 Operationalising inclusive research approaches to belonging

It has been highlighted that the values-based origins of inclusive research are generally taken as sufficient justification for using inclusive research approaches (Nind, 2014; Walmsley et al., 2018). To provide greater clarity about how this values-base is operationalised it is also necessary to interrogate the methods used and the ways their accessibility and flexibility is ensured. This greater transparency will also aid in developing mechanisms to assess how collaboration is enacted. Table 4 maps each of the 16 included studies to show which phases of each study were self-reported to have been conducted collaboratively.

| Article | Design description | Phase 1 initiating | Phase 2 planning | Phase 3 doing | Phase 4 sense making | Phase 5 sharing | Phase 6 reflecting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milner and Kelly (2009) | Participatory Action research | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Dias et al. (2012) | Emancipatory research | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Koenig (2012) | Inclusive research | ✓ | |||||

| Haigh et al. (2013) | Inclusive co-production | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| García Iriarte et al. (2014) | Participatory framework | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Frawley and Bigby (2015) | Collaborative group method | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Heffron et al. (2018) | Participatory Action Research | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Wilton et al. (2018) | Participatory research project | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Mooney et al. (2019) | Inclusive research design | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Renwick et al. (2019) | Inclusive research project | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Robinson et al. (2020) | Participatory research | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Rojas-Pernia et al. (2020) | Inclusive research | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Witsø and Hauger (2020) | Participatory action research design and collaborative group approach | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Martin et al. (2021) | Inclusive research design and participatory and advisory approach | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Kaley et al. (2021) | Inclusive research | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Power and Bartlett (2018) | Participatory design | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Researchers with intellectual disabilities were involved in the initiating phase in half of the articles (8), including activities like talking to people with intellectual disabilities about what matters to them and identifying the research problem. In 11 of the articles, involvement in the planning phase was discussed, including activities such as suggesting topics and discussing the relevance of the area of study to the lives of people with intellectual disabilities. All but one article (Koenig, 2012) included researchers with intellectual disabilities in the doing phase, encompassing core activities like recruitment and data collection. Collaboration in at least some elements of sense making, including the core activity of data analysis were reported in all articles. In 14 articles, collaboration was described in the sharing phase, which involves activities of research dissemination. Only four of the 16 articles referenced collaborative reflecting. Mapping the included studies in this way provides an additional layer of scrutiny to the authors claims of having inclusively conducted their studies. The high level of reported involvement of researchers across phases also suggests that the sample does demonstrate the perspective of people with intellectual disabilities about a sense of belonging in their lives.

3.3 Key themes of belonging

Analysis of the thematic content across the 16 articles generated a clear picture of the enablers to a sense of belonging for people with intellectual disabilities. Table 5 shows the key findings of the included articles matched to the themes from the literature.

| Study | Positioned belonging | Belonging as identity | Belonging as relational | Belonging in relation to place | Belonging as a contributor to society |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milner and Kelly (2009) | Psychological safety | Social identity; self-determination | Mutuality and reciprocity | Participatory expectations | Valued contribution |

| Dias et al. (2012) | Segregated groups | Desire to be part of wider society | |||

| Koenig (2012) | Intellectual disability's identity; separating from other people with intellectual disabilities | ||||

| Haigh et al. (2013) | Choice and independence | Relationships | Activities | Valuable social roles | |

| García Iriarte et al. (2014) | Choice and control | Feeling included in society | Activities in the local community | ||

| Frawley and Bigby (2015) | Self-advocacy | Social connections | Self-advocacy group membership | Doing things that matter | |

| Heffron et al. (2018) | Economic environments | Social environments | Physical environments | Community participation | |

| Wilton et al. (2018) | Significance of place (shopping and consumption) | ||||

| Mooney et al. (2019) | Practical barriers to community involvement | ||||

| Renwick et al. (2019) | Interacting with similar people | Engaging in social relationships | Finding a good fit | Meaningful roles in the community | |

| Robinson et al. (2020) | Relationships and positive connections; comfort and safety in relation to people | Comfort and safety in place | Being valued and recognised | ||

| Rojas-Pernia et al. (2020) | Social change is needed for inclusion | Relationships are important | Desire to feel part of something | ||

| Witsø and Hauger (2020) | Family and friendships are important | Leisure activities | |||

| Martin et al. (2021) | Mobile technology increases social inclusion with family and friends | Mobile technology increases social inclusion at work and volunteering | |||

| Kaley et al. (2021) | Local friendship groups; time with family and friends | Self-advocacy group membership | Being an active member of the community | ||

| Power and Bartlett (2018) | Democratic spaces | Insider status spaces | Relational spaces; friendship groups | Spaces of incognito; spaces of rest and memory; making home meaningful; gardening; dog walking |

All included studies had findings which aligned with at least one theme from the literature, and findings from 10 of the 16 aligned with at least three themes from the literature. Findings are discussed in relation to each of the five themes identified.

3.3.1 Positioned belonging

Positioned belonging relates to the cultural context into which we are born and was discussed in relation to contextualising the experiences of belonging and not belonging of people with intellectual disabilities in neo-liberal societies (Renwick et al., 2019). Five of the articles had findings which aligned with this theme. All studies were conducted in neo-liberal societies, and the practical barriers to community involvement this entailed for financially vulnerable people with intellectual disabilities was highlighted in one study (Mooney et al., 2019). Heffron et al. (2018) also discussed the impact of economic environments on feeling a sense of belonging. The isolation and separation from community that can occur in the shift towards the personalisation of supports in a neo-liberal context was also highlighted (Power & Bartlett, 2018). These authors identified the importance of involvement in democratic spaces like community gardens where contact with a range of different people occurs, to increase the social inclusion and sense of belonging experienced by people with intellectual disabilities. Psychological safety was identified as key to creating the context for social inclusion and a felt sense of belonging. The need for significant social, cultural and political change to occur if greater social inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities is to be achieved was also identified (Rojas-Pernia et al., 2020).

3.3.2 Belonging as identity

The formation of individual identities for people with intellectual disabilities was discussed in seven of the articles. Two aspects of identity appeared to sit in tension in the articles that identified the centrality of identity to belonging. On one hand the importance of being part of a peer group with shared experience of disability was seen as important (Frawley & Bigby, 2015) while on the other, some sought to distance themselves from the intellectual disabilities label (Koenig, 2012). In the framework of belonging developed by Renwick et al. (2019), interacting with similar people was central to a sense of belonging. Having experiences of being an “insider” were considered important (Power & Bartlett, 2018). Frawley and Bigby (2015) found that membership in a self-advocacy group was central to developing a sense of belonging for group members with intellectual disabilities. On the other hand, Koenig (2012) found that people with intellectual disabilities had challenges determining which “camp” (p. 220) they belonged to and would sometimes seek to separate themselves from other people with disabilities, which impacted on their capacity to experience a sense of belonging. Independence and control were found to be important to belonging in three of the articles and was expressed as a need for self-determination (Milner & Kelly, 2009), choice and independence (Haigh et al., 2013) and choice and control (García Iriarte et al., 2014). Therefore, both agency and interdependence were important to belonging in the context of identity formation.

3.3.3 Belonging as relational

Recognition of the relationality of belonging was prevalent across the studies, with 12 containing findings related to this theme. Feeling included in the wider society was important to people with intellectual disabilities (García Iriarte et al., 2014) and this sense of inclusion applied in a range of social environments (Heffron et al., 2018). People with intellectual disabilities in the reviewed studies identified relationships as key to belonging (Haigh et al., 2013; Renwick et al., 2019; Robinson et al., 2020; Rojas-Pernia et al., 2020) and particularly relationships with family and friends (Kaley et al., 2021; Witsø & Hauger, 2020), and relationships within self-advocacy groups (Frawley & Bigby, 2015). It was also found that mobile technology increased social inclusion with family and friends (Martin et al., 2021).

Mutuality and reciprocity in social relations was an important enabler to a sense of belonging (Milner & Kelly, 2009). The significance of relational spaces like friendship groups was noted (Kaley et al., 2021; Power & Bartlett, 2018). Renwick et al. (2019) acknowledged the importance of engaging in social relationships, and belonging was found to be enhanced when those connections were positively experienced (Robinson et al., 2020). On the inverse, the relative absence of positive relational experiences and consequent feelings of loneliness had a negative impact on a sense of belonging (Mooney et al., 2019).

3.3.4 Belonging and place

Belonging and place refers to the relationship to place experienced by people with intellectual disabilities and incorporates physical, social, and psychological spaces and activities related to those spaces. Insights into this theme were reported in 12 articles. The participatory expectations of people with intellectual disabilities in places were found to impact on a sense of belonging (Milner & Kelly, 2009), related to the need to feel a sense of comfort and safety in places (Robinson et al., 2020), or “finding a good fit” (Renwick et al., 2019, p. 945). Physical environments were important (Heffron et al., 2018) and several studies identified that activities undertaken in particular locations were central to a sense of belonging (García Iriarte et al., 2014; Haigh et al., 2013; Power & Bartlett, 2018; Wilton et al., 2018; Witsø & Hauger, 2020). Disability-specific spaces were considered important (Dias et al., 2012), including self-advocacy groups (Frawley & Bigby, 2015; Kaley et al., 2021), as were mainstream community spaces like shopping centres (Wilton et al., 2018).

3.3.5 Belonging as contribution

This theme encompasses the opportunities people with intellectual disabilities have to contribute to society and 10 of the 16 articles reported findings related to this theme. Being an active member of the community was considered essential to belonging for people with intellectual disabilities (Kaley et al., 2021), as was doing things that mattered to people with intellectual disabilities themselves and to others (Frawley & Bigby, 2015). For some, this manifested as a desire rather than an experience to be part of the wider society (Dias et al., 2012; Rojas-Pernia et al., 2020). For others, it was about the positive appraisal by others through being valued and recognised (Robinson et al., 2020) and feeling that their contribution was valued by wider society (Milner & Kelly, 2009). A pathway to achieving this was seen to be through people with intellectual disabilities assuming valued social roles (Haigh et al., 2013), and performing meaningful roles in the community (Renwick et al., 2019). The use of mobile technology by people with intellectual disabilities was found to increase their social inclusion in work and volunteering roles (Martin et al., 2021).

4 DISCUSSION

The aim of this review was to better understand the contribution of inclusive research approaches to the study of belonging. Consistent with the findings of Fulton et al. (2021) belonging was rarely the focal concern of the included studies but was rather an emergent finding of broader empirical work on social inclusion with people with intellectual disabilities. Arguably, this suggests the importance and relevance of the concept of belonging to understanding the enablers to the social inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities. The findings of this review suggest that belonging is both a critical pre-cursor and a central component to people with intellectual disabilities experiencing social inclusion. Further, belonging might be understood conceptually and operationally as a contextually based process characterised by reciprocity, shaped by emotional, social, and political power, and affected in the spaces, places, and relationships of daily life.

The first research question concerned the characteristics of the inclusive research approaches used and the nature of collaboration between researchers with and without intellectual disabilities across the phases of the research. The growth of inclusive research during the period covered by this review can be seen to result in the democratisation of some aspects of academic research, including for example the contribution of co-researchers being sometimes acknowledged through authorship in academic publications. It was found that the labels used to designate roles within research teams were not necessarily or reliably indicative of the actual contribution of co-researchers in the research or in academic career-enhancing activities such as publication. Overall, these findings are promising in relation to the goal of inclusive approaches to democratise the research process. However, given that people with intellectual disabilities were co-authors in under half the articles but were involved in data analysis in all the included articles, there is clearly room for further democratisation concerning authorship.

Self-reported levels of co-production across phases of the research were high, particularly at the data collection and data analysis phases. There was low reporting of the use of reflexivity and reflecting in the studies. Overall, low scores were observed concerning the reflexivity measure, item 10 in QualSys quality assessment tool (Kmet et al., 2004). Similarly, a low incidence of the inclusion of a reflecting phase (Strnadová et al., 2022) in the sampled studies was noted. Reflexivity concerns engagement with the positionality of academic researchers within the research process and is a useful proxy measure for the reflecting phase in co-production. Only two articles scored highly in relation to reflexivity (Dias et al., 2012; Haigh et al., 2013), and these two articles also addressed the reflecting phase. Both articles scored strongly overall using the QualSys tool (Kmet et al., 2004). This outcome suggests that research with a high level of co-production can also score highly in relation to overall academic quality. Significantly, both these articles were co-authored by co-researchers with intellectual disabilities, in the case of Dias et al. (2012) as lead author.

Limited discussion of reflexivity and reflection may simply be a strategic decision by authors to address constrained word counts in journal publications. However, the high proportion of articles that did not address them warrants consideration. Reflexivity and reflecting are interrelated concepts, and both are important to addressing and developing core aspects of inclusive research, namely, collaboration, the co-generation of new knowledge, and striving to make accessible and democratise the academic research enterprise. Incorporating researcher reflexivity and a reflecting phase in research projects is important to build on what works and avoid replicating shortcomings in future studies. While the values-based origins of inclusive research have been previously highlighted (Nind, 2014; Walmsley et al., 2018) and an axiological orientation is generally taken as sufficient justification for using inclusive research approaches, the findings from this review suggest the need for more consistent consideration and articulation of reflexivity and reflection as a way to more transparently demonstrate claims to inclusion in research about belonging.

The second research question was answered by mapping the inclusive research thematic findings about belonging to the five interconnected themes identified in the wider belonging literature by Strnadová et al. (2018). The inclusive research findings included in this review extended and deepened the themes identified in the wider literature by providing more nuanced insights, for example by identifying a demonstrable tension between the desire for belonging and lived experience in the lives of people with intellectual disabilities. This tension was identified in disability and mainstream spaces (Milner & Kelly, 2009; Power & Bartlett, 2018) and in the stated desire for both independence (Haigh et al., 2013) and interdependence (Renwick et al., 2019). The desire for independence does not appear to negate the need for group affiliation and membership with other people with disabilities (Koenig, 2012).

Belonging and social inclusion are not a simple matter of moving people from one kind of space or place to a different kind of space or place. Belonging does not necessarily flow from social inclusion practices which can in effect force people to engage with the community as an arbitrary act of inclusion. Rather belonging is a more nuanced issue of felt identity and having the choice to develop identity in a safe space of like-minded people or people of similar experience. Arguably, enabling this identity development is a foundation for building confidence to develop a sense of belonging in the broader community. The tension between wanting to be with people with shared experience and wanting to be part of the wider community is of interest and has potential policy implications given the inclination towards framing social inclusion as a shift away from disability exclusive spaces and places.

Findings from this review suggests that unravelling the complex interplay between the desire for agency and the need for meaningful relationships is central to understanding belonging in the lives of people with intellectual disabilities. Self-exclusion and self-censorship and a preference for spending time with people with shared experiences of living with disabilities have been reported in the literature (Hall, 2010; Salmon, 2013). Overall, the studies reviewed here identified a tension between the lived experience of daily life for people with intellectual disabilities and the normative and ethical frameworks that shape our societies (Meininger, 2010). This finding suggests that social inclusion as a metric of community presence and employment does not necessarily lead to belonging (Simplican et al., 2015).

Inclusive research studies suggest a sense of safety is central to experiencing a sense of belonging. The tension between the desire to belong and the lived experience of exclusion was consistently acknowledged through the presence or lack of physical, psychological, and epistemological safety. This finding suggests the central value of an insider perspective and that the insights derived from inclusive approaches in the social sciences allows research questions to be answered that it would not otherwise be possible to answer in the same way (Nind & Vinha, 2012).

The included articles also extend understanding of the enablers of belonging in calling into focus the need for broader cultural and systemic change to create the context for people with intellectual disabilities to have opportunities to experience a sense of belonging (Rojas-Pernia et al., 2020). Only then might the lived experience of social inclusion move beyond transitory moments of belonging in a context of social exclusion (Power, 2013) to more enduring forms of belonging in a context of inclusion.

The review found that in a neo-liberal context, social inclusion, as narrowly measured by workforce participation and independence remains unachievable for many people with intellectual disabilities and does not necessarily act to enable a sense of belonging (Renwick et al., 2019). This challenge has been identified as a tension between the desire of people with intellectual disabilities to be more involved and the multiple barriers that limit their involvement (Hall, 2017). The research undertaken in intellectual disabilities studies suggests that belonging, as it is conceived and experienced by people with intellectual disabilities, is more nuanced and diverse than can be accommodated within the narrow parameters of social inclusion (Simplican et al., 2015). Renwick et al. (2019) reported that young people with intellectual disabilities viewed a feeling of belonging to be universally desirable. However, May (2011) posits that belonging or not belonging are not inherently positive or negative but rather they are contextual and relational. In the context of the lives of people with intellectual disabilities this point is particularly salient, as the experience of social exclusion as a result of policies aimed at social inclusion has been reported by people with intellectual disabilities (Hall, 2010; Milner & Kelly, 2009; Strnadová et al., 2018).

4.1 Limitations

People with intellectual disabilities are not a homogenous group and those involved in the included studies are neither homogenous nor representative. As noted elsewhere (Jones et al., 2020; Nind & Strnadová, 2020) the perspective of people with profound intellectual disabilities are under-represented in the research literature, and the inclusive social inclusion and belonging literature is no exception. Attention to including the unique perspectives of this group should be considered in future research.

4.2 Future research

This review focused primarily on enablers to a sense of belonging for people. Future research should consider the main inhibitor to belonging identified by Strnadová et al. (2018), which was stigma, often expressed as prejudice and bullying. It is important to ascertain whether people with intellectual disabilities themselves also perceive this to be the primary inhibitor to a sense of belonging in their lives. Also, while the phases of co-production has utility in mapping reported involvement at different phase of the research, further work, as also identified by Di Lorito et al. (2018), is required to define and measure precisely what involvement in co-production looks like both for researchers with and without intellectual disabilities.

This systematic review about inclusive research undertaken in relation to belonging was not conducted inclusively. It was conducted as part of a doctoral study using an inclusive advisory approach but the project advisors with intellectual disabilities did not participate in the systematic review phase. Primarily this decision was made for two reasons, (1) the aspects of the project that the advisor's felt they wanted and could best contribute to, and (2) the time restraints for this part of the doctoral project. It is acknowledged that this is an important area of inclusive scholarship to be developed and addressed in future studies.

5 CONCLUSION

Belonging has been identified as important to the social inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities (Renwick et al., 2019). Without a subjective sense of belonging at its core, efforts towards social inclusion can be experienced as social exclusion (Hall, 2010; Milner & Kelly, 2009). Inclusive research approaches to belonging may add subjective, relational, and socio-culturally located dimensions to social inclusion discourses (Hall, 2013; May, 2011; Strnadová et al., 2018). Belonging may provide researchers, policy makers and practitioners with novel and responsive frameworks to support people with intellectual disabilities to develop a sense of being connected and “at home” in themselves and their communities and in the research conducted about these.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Open access publishing facilitated by University of New South Wales, as part of the Wiley - University of New South Wales agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.