A Q-methodology study among caregivers of people with moderate intellectual disabilities on their clients’ health care: An example in oral health

Abstract

Background

People with intellectual disabilities have less favourable outcomes in—among others—oral health variables, compared to their peers without intellectual disabilities. Before being able to develop target interventions for caregivers, all their prevailing viewpoints regarding oral hygiene need to be identified.

Methods

This Q-methodology study—conducted among 40 caregivers of care-dependent Institutionalized living persons with moderate intellectual disability—used by-person factor analysis to reveal clusters of caregivers based on the way their statements were sorted.

Results

A 4-factor solution was chosen based on both the Q-sorting and the interviews. The four factors identified were responsible and perseverant, motivated but aware of obstacles, social minded and knowledgeable and concerned and insecure.

Conclusion

Q-methodology can be used to determine the different attitudes that caregivers have regarding oral health care. Developing a tool to determine into which factor caregivers should be categorized may be the next step in tailoring oral health instruction.

1 BACKGROUND

People with intellectual disabilities (ID) tend to have less favourable outcomes with different kinds of health-related issues compared to their peers without intellectual disabilities (Allerton, Welch, & Emerson, 2011; van Timmeren et al., 2017; Trollor et al., 2016). Reasons for these differences include their dependence on caregivers and the problems these caregivers encounter while providing adequate care. In addition, concerning oral health, worse health outcomes and lower levels of oral hygiene have been reported in institutionalized people with intellectual disabilities (Glassman & Miller, 2003). A systematic review including 27 studies concluded that people with intellectual disabilities have both a greater severity of periodontal disease, as well as a higher prevalence of the disease, and poorer levels of oral hygiene than individuals in the general population. Furthermore, it was reported that although the total level of dental caries (tooth decay) in people with intellectual disabilities was comparable to individuals in the general population, the proportion of treated/untreated caries lesions was lower in people with intellectual disabilities, indicating a higher number of untreated cavities in this group. (Anders & Davis, 2010).

Dental disease can be considered a disease that can largely be prevented by applying an adequate level of oral hygiene and following a strict but simple dietary regimen of eating/drinking products with fermentable carbohydrates not more than 8 times per day. Therefore, dental health professionals usually try to improve oral health through dietary counselling and by trying to improve the level of oral hygiene. Whether these interventions should be targeted to the clients or their caregivers depends on the clients’ levels of motor skills and intellectual abilities.

Institutionalized living persons with intellectual disabilities largely depend on others, usually their caregivers, for daily toothbrushing. As in other fields of health care where behaviour plays an important role, the caregiver's attitudes towards oral health are of vital importance for the level of the delivered preventive oral care (Jerkovic et al., 2009; Kaye, Fiske, Bower, Newton, & Fenlon, 2005; Riley, Gilbert, & Heft, 2006; Stenberg, Håkansson, & Akerman, 2000). A study by Riley et al. (2006) also found that people with favourable attitudes about dentists and dental care reported a higher number of preventive and restorative dental visits and a lower prevalence of toothache, tooth sensitivity and gingivitis than people with negative attitudes. Therefore, changing people's attitudes may provide ways to improve the quality of delivered oral health care and oral hygiene. From the perspective of Institutionalized living persons with intellectual disabilities, their caregiver's position towards toothbrushing may therefore have a large impact on their oral health. Knowing what attitudes a caregiver has towards oral health and oral health-related behaviour may provide useful information concerning possible ways to target preventive interventions. By knowing their viewpoints, dental care professionals may increase the involvement of caregivers in a more effective way. Publications concerning attitudes of caregivers for people with intellectual disabilities towards oral health in their clients are scarce. It has been reported that caregivers find the provision of oral care difficult to execute (Dougall & Fiske, 2008). Problems they may encounter include having doubts about their role in the oral care of their clients, undermining the autonomy of clients, difficulty fitting the task into their daily schedules and their lack of practical skills. Additionally, another study reported that caregivers also encounter several difficulties in providing adequate oral health care from the clients themselves: residents biting the toothbrush, not opening their mouths for toothbrushing or otherwise refusing oral health care (Thole, Chalmers, Ettinger, & Warren, 2010).

Concerning educational interventions for caregivers, Fickert and Ross (2012) reported that an educational intervention improved caregivers’ attitudes towards performing oral care, which is in line with additional data from an oral health education programme for the nursing staff in special housing facilities for the elderly that indicated that trainees with a low level of healthcare education benefitted the most (Paulsson, Söderfelt, Fridlund, & Nederfors, 2001). A study of nursing home caregivers found that an oral healthcare education programme for nursing home caregivers was well-received and resulted in improved levels of oral healthcare knowledge and attitudes. Moreover, it was found that when knowledge and attitude scores improved, the quality of the delivery of oral health care did as well (Frenkel, Harvey, & Needs, 2002). These findings were confirmed in a cluster-randomized intervention trial that showed a significant improvement in the oral health knowledge among caregivers after oral health education was provided (Khanagar et al., 2014). They concluded that educating caregivers about assisting or enabling residents for maintaining oral hygiene is essential. However, less favourable results were also reported. A recent study by Albrecht, Kupfer, Reissmann, Mühlhauser, and Köpke (2016) did not find evidence of sufficient quality to establish any meaningful effects of educational interventions for caregivers on any measure of resident's oral health.

Before being able to develop target interventions for caregivers, one should know all prevailing attitudes that are present among caregivers of people with intellectual disabilities. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore all prevailing viewpoints that caregivers of institutionalized persons with intellectual disability in the Netherlands have about oral hygiene. For this purpose, a Q-methodology study was performed. This method is a hybrid qualitative and quantitative research method (Cross, 2005) that has been used increasingly in healthcare studies over the past decade (Akhtar-Danesh, Baumann, & Cordingley, 2008; Barbosa, Willoughby, Rosenberg, & Mrtek, 1998; Dziopa & Ahern, 2011; Mason, Baker, & Donaldson, 2011; Tielen, van Exel, van Buren, Maasdam, & Weimar, 2011; Vermaire, Hoogstraten, van Loveren, Poorterman, & van Exel, 2010).

2 METHODS

2.1 Procedure

The study was conducted among caregivers of care-dependent Institutionalized living persons with moderate intellectual disability (IQ 40-55) in the Netherlands.

From May 2014 to January 2015, caregivers of Institutionalized living persons with a moderate intellectual disability were asked to participate in this study. These caregivers were all working at different institutions for people with intellectual disabilities in various parts of the Netherlands (both rural and urban).

They were informed about the project by the institution's dentist during regular check-up appointments of their clients. When they agreed to participate, a telephone conversation with one of the authors (AE/GS) was arranged to give additional information about the project and ask for participation. As both gender and education level influence attitudes about oral health care (Al-Omiri, Barghout, Shaweesh, & Malkawi, 2012; Schulz, Kunst, & Brockmann, 2016), a total of six target groups were composed based on gender (male or female) and education level (low, medium and high).

A total of 40 caregivers were included in this study (Table 1). This sample, in Q-methodology called the P-set, consisted of thirteen men (32.5%) and twenty-seven (67.5%) women. Eighteen (45%) were aged 40 years or younger and twenty-two (55%) were over 40. Five (12.5%) had a low education level, twenty (50%) medium and fifteen (37.5%) a high education level. According to recent numbers (2014) from the Dutch association for the care for people with intellectual disabilities (VGN), 18% of caregivers in the Netherlands are men and 82% are women. Their mean age is 41.8 years. Due to the predicted increasing retirement of caregivers heading towards 2023, the mean age is expected to descend. Concerning education, 22% had a low level, 53% had a medium level, and 25% had a high level.

| P-set % | NL (VGN) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 32.5 | 18% |

| Female | 67.5 | 82% |

| Age | ||

| <40 years | 45 | Mean age 41.8 years |

| ≥40 years | 55 | |

| Education level | ||

| Low | 12.5 | 22% |

| Medium | 50 | 53% |

| High | 37.5 | 25% |

2.2 Development of the statement set

A total of 92 initial statements regarding oral health and oral health behaviour were collected from interviews with an experts panel consisting of two intellectual disability dentists, two intellectual disability physicians, two dental hygienists, two parents, two caregivers and two remedial educationalists. Furthermore, scientific and popular literature and the Internet (websites of various clients’ associations, Internet forums and social media) were searched.

To categorize the collected statements, the health belief model (HBM) was used. The HBM was first described in 1988 (Rosenstock, Strecher, & Becker, 1988) and contains seven dimensions of health behaviour: susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, self-efficacy and perceived threats, to which each statement refers to.

To achieve a workable set, the Q-sample or Q-set, the total amount of statements was reduced by eliminating redundant statements as well as negatively contradicting statements. In addition, statements that eventually were considered not relevant by the earlier described expert panel were discarded. The relevance of all statements was determined by how often the specific statement was mentioned during the collection of the statements. Dental care professionals and caregivers of people with intellectual disabilities were asked to assign the most relevant and irrelevant statements. The final sample consisted of 35 statements, which were numbered randomly and were printed on separate cards.

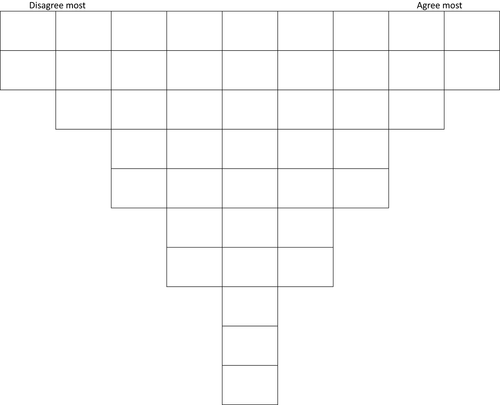

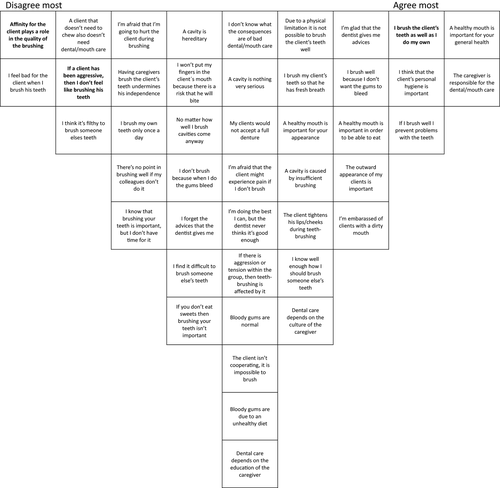

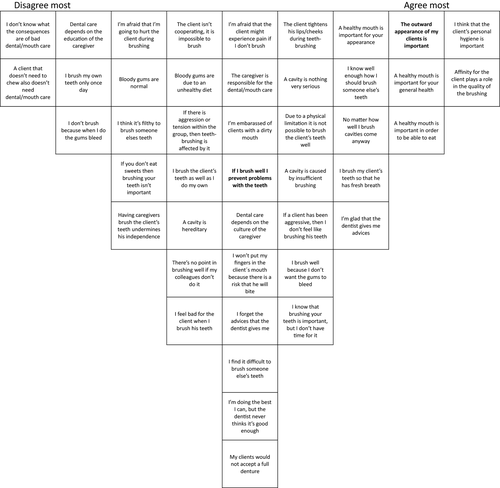

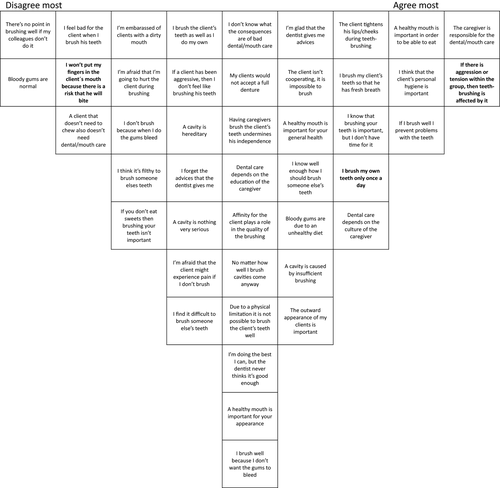

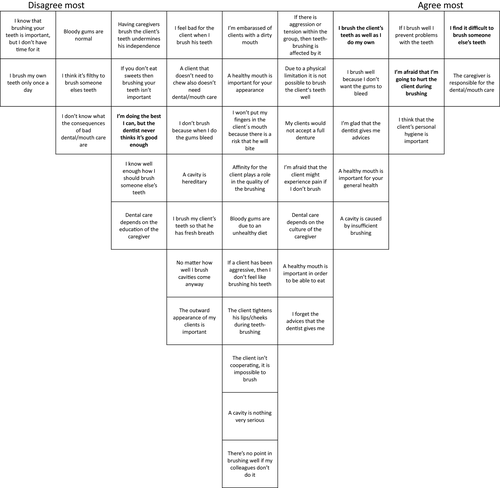

All participants were visited at the institution they worked at by one of the researchers (AE or GS). They were instructed to first make three piles of cards: one with statements they agreed with, one they disagreed with and one they felt neutral about. After that, they were asked to select the cards with statements they most strongly disagreed with and list them on a response sheet (Figure 1) in the left columns (-4, -3, etc.) and to fill the columns until all the cards from the “disagree pile” were used. This procedure was repeated with the “agree pile” and finally the “neutral pile.” This rank-order process resulted in individual Q-sort tables or Q-sorts (Figures 2, 3, 4 & 5; Table 2).

| Statements | Factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1) Perceived susceptibility | |||||

| 1. Bloody gums are due to an unhealthy diet | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2. A cavity is caused by insufficient brushing | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3. A cavity is hereditary | 0 | −1 | 0 | −1 | |

| 4. Bloody gums are normal | 0 | −1 | −2 | −2 | |

| 5. A client that doesn't need to chew also doesn't need dental/mouth care | −1 | −2 | −2 | −1 | |

| 6. If you don't eat sweets then brushing your teeth isn't important | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | |

| 2) Perceived severity | |||||

| 7. A cavity is not very serious | 0 | 1 | −1 | 0 | |

| 8. I don't know what the consequences of bad dental/mouth care are | 0 | −2 | 0 | −1 | |

| 9. My clients would not accept a full denture | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 10. I brush well because I don't want the gums to bleed | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 11. I don't brush because when I do the gums bleed | −1 | −2 | −1 | −1 | |

| 3) Health motivation | |||||

| 12. I'm embarrassed of clients with a dirty mouth | 1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | |

| 13. There's no point in brushing well if my colleagues don't do it | −1 | −1 | −2 | 0 | |

| 14. I brush my own teeth only once a day | −1 | −2 | **1 | −2 | |

| 15. The outward appearance of my clients is important | 1 | *2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 16. I think it's filthy to brush someone else's teeth | −2 | −1 | −1 | −1 | |

| 17. The caregiver is responsible for the dental/mouth care | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| 18. I think that the client's personal hygiene is important | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| 19. I brush the client's teeth as well as I do my own | *2 | 0 | 0 | *1 | |

| 4) Perceived benefits | |||||

| 20. I brush my client's teeth so that he has fresh breath | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | |

| 21. If I brush well I prevent problems with the teeth | 1 | **0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 22. I'm afraid that the client might experience pain if I don't brush | 0 | 0 | −1 | 1 | |

| 23. A healthy mouth is important in order to be able to eat | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 24. A healthy mouth is important for your general health | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| 25. A healthy mouth is important for your appearance | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 5) Perceived barriers | |||||

| 26. The client isn't cooperating; it is impossible to brush | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 27. I know that brushing your teeth is important, but I don't have time for it | −1 | 0 | 1 | −2 | |

| 28. I feel bad for the client when I brush his teeth | −2 | −1 | −1 | −1 | |

| 29. I'm afraid that I'm going to hurt the client during brushing | −1 | −1 | −1 | **1 | |

| 30. I won't put my fingers in the client′s mouth because there is a risk that he will bite | −1 | 0 | *−2 | 0 | |

| 31. Having caregivers brush the client's teeth undermines his independence | −1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | |

| 32. The client tightens his lips/cheeks during teeth-brushing | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| 33. If there is aggression/tension within the group, then teeth-brushing is affected by it | 0 | 0 | **2 | 0 | |

| 34. Due to a physical limitation it is not possible to brush the client's teeth well | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6) Self-efficacy | |||||

| 35. I find it difficult to brush someone else's teeth | −1 | 0 | −1 | **2 | |

| 36. I know well enough how I should brush someone else's teeth | 0 | 1 | 1 | −1 | |

| 37. If a client has been aggressive, then I don't feel like brushing his teeth | *−1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 38. No matter how well I brush, cavities come anyway | −1 | 1 | 0 | −1 | |

| 7) Cues to action | |||||

| 39. I forget the advice that the dentist gives me | −1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 40. I'm doing the best I can, but the dentist never thinks it's good enough | 0 | 0 | 0 | *−1 | |

| 41. I'm glad that the dentist gives me advice | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 42. Dental care depends on the culture of the caregiver | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 43. Dental care depends on the education of the caregiver | 0 | −1 | 0 | −1 | |

| 44. Affinity for the client plays a role in the quality of the brushing | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

- * significant at p < 0.05; ** significant at p < 0.01

Directly after the completion of the Q-sort, the respondents explained in a short interview the two statements they most agreed with and they most disagreed with to help with interpreting the results after analysis. This interview also included some questions about the respondents’ background to fit them into the correct target group.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using PQ method 2.11 (Schmolck, 2002).

Using a by-person factor analysis (principal components with varimax rotation), clusters of participants were identified based on the way their statements were sorted, the so-called factors or frames (Dziopa & Ahern, 2011; van Exel & Graaf, 2005; Jedeloo & van Staa, 2009). Each factor was interpreted and described based on the statements that statistically and significantly distinguished the factor from the others and from the comments made by the respondents during the interview. During the interviews, one person appeared to have great difficulty reading, and the results of that Q-sort were not in concordance with the interview that was held afterwards; this Q-sort was excluded from further analysis.

3 RESULTS

A 4-factor solution demonstrated the most informative interpretation of the results of the Q-sorts and the interviews. All found factors are described below by reporting the identifying and distinguishing statements and are illustrated by caregivers’ quotes as derived from the interviews.

3.1 Factor 1: Responsible and perseverant

Caregivers in factor 1 have a very strong sense of responsibility. They completely agree with statement 17: “The caregiver is responsible for the dental/mouth care,” because they realize that most clients are not able to maintain their personal hygiene sufficiently by themselves: “Our clients won't take any initiative to brush their teeth themselves. In fact, the average client couldn't care less about taking a shower, using deodorant or the way they are dressed.”

Besides the dependency, caregivers feel responsible for the client's general health (statement 24: “A healthy mouth is important for your general health.”) “I know that bad oral health can cause other illnesses, like cardiovascular diseases and diabetes.”

Additionally, these caregivers feel that every client needs toothbrushing, regardless of their diet (statement 5: “A client that doesn't need to chew also doesn't need dental/mouth care.”). “The mouth just needs to be clean. Also, gastric juice can cause problems with your teeth. And even if you don't have teeth, you could get lesions or inflammation. Or very bad breath, of course.”

They are confident that they can reduce oral problems through proper oral hygiene (statement 21: “If I brush well, I prevent problems with the teeth”): “If you just brush the teeth in the morning and the evening, like you do with your own teeth, clients are likely to have fewer cavities or gum diseases. If you wouldn't brush at all, you would get problems unquestionably.”

Unlike caregivers in factors 2 and 3, they agree with statement 19: “I brush the client's teeth as well as I do my own.” People in factor 4 also slightly agree. Factor 1 is somewhat more distinct: “I don't want to get any cavities and I don't like my gums being inflamed, so I don't want that for my clients either. I'm doing the very best I can.”

Furthermore, they will not accept any excuses to skip toothbrushing. They will not agree with statements 28: “I feel bad for the client when I brush his teeth”: “You have a lot more reason to feel sorry for your clients if you don't brush,” and 37: “If a client has been aggressive, then I don't feel like brushing his teeth”: “It is possible to brush anytime. Even if the client clenches his teeth together, there is always a way to have it done.” Personal preferences are not accepted in this factor (statement 44: “Affinity for the client plays a role in the quality of the brushing”): “I think it is bad attendance if you are guided by affinity. It is not supposed to have any influence.” “I brush anyone just as good and just as frequently. I don't care if it is a man or a woman or someone with filthy teeth.

This factor was called responsible and perseverant.

3.2 Factor 2: Social minded and knowledgeable

The caregivers within this factor consider personal hygiene as a top priority, because they feel accountable for how their clients are approached by outsiders. Consequently, they are very concerned about their clients’ appearance (statements 15: “The outward appearance of my clients is important” and 25: “A healthy mouth is important for your appearance”): “They already have a disadvantage causing people to treat them differently. If they look dirty in addition, they will be even more excluded from society.” “The way clients are approached by the outside world is linked to their appearance and smell, or people may avoid them.” “The least we can do is to make sure their teeth are brushed. Personally, I would rather talk to someone who has clean teeth as well.”

They also feel that affinity with the client influences the oral care (statement 44: “Affinity for the client plays a role in the quality of the brushing”). “You need to have certain affinities to work with people with intellectual disabilities. When you have more affinity, you also put on the diaper better, you have more focus on certain things.”

These caregivers highly disagree with statement 8: “I don't know what the consequences of bad dental/mouth care are” “I think I do know the consequences. That is my motivation to do it the right way,” and statement 5: “A client that doesn't need to chew also doesn't need dental/mouth care.” “If you're talking about pathogens, oral care is one of the most important things. Clients might get aspiration pneumonia, regardless of their need to chew.”

They also disagree with statement 11: “I do not brush because when I do, the gums bleed” “I know it does not hurt and that it is just a sign that there can be an infection. So, of course, caution is needed, but I brush anyway.” “Bleeding gums are no excuse to skip the brushing. You definitely need to brush to eliminate the cause of the bleeding.”

However, while caregivers in factors 1, 3 and 4 agree with statement 21: “If I brush well I prevent problems with the teeth,” people in factor 2 are neutral. This indicates they find other consequences of not brushing more important than the consequences for the teeth themselves.

This factor was called social minded and knowledgeable (Figure 3).

3.3 Factor 3: Motivated but aware of obstacles

These caregivers are highly aware of the obstacles that are encountered when providing oral care to people with intellectual disabilities. They completely agree with statement 33: “If there is aggression/tension within the group, then teeth-brushing is affected by it”: “I might skip the tooth brushing of this particular person to prevent myself from getting hit.” “This happens sometimes; it varies from day to day. An aggression incident also causes a great administrative burden. The high workload influences the tooth brushing.”

The workload also affects the toothbrushing (statement 27: “I know that brushing your teeth is important, but I don't have time for it”): “In particular, in the morning. In the evening, it is workable, but in the morning, the tooth brushing slips very easily. People have to go to day care, and you have six people tumbling out of bed, and you've only got until 9:30 am to get them ready for work.”

However, these caregivers are also conscious of the need for toothbrushing and they feel responsible for it. Like those in factor 1, they totally agree with statement 17: “The caregiver is responsible for the dental/oral care.” “Of course, it is our responsibility. It is very easy: it is your job, that's what you get paid for. The clients won't do it by themselves; they are just not able to.”

They also agree with statement 23: “A healthy mouth is important in order to eat.” “Because if you have pain in your mouth, you cannot eat anymore. And this is where the first digestion starts.”

Nevertheless, factor 3 is the only factor that agrees with statement 14: “I brush my own teeth only once a day.”

The caregivers in this factor will not let the risk of biting stand in their way (statement 30: “I will not go with my fingers into the mouth of the client, because of the risk of biting”). “It does not obstruct the tooth brushing, but I do take caution, because some clients also bite on purpose.” Others dill not see any risk: “I'm not afraid of biting. It never happened to me.”

Indifferent colleagues are not considered a problem either: (statement 13: “It's no use to brush well if my colleagues won't do it”). “If my colleague doesn't perform his responsibility, there is even more reason for me to do the brushing very well.” “First of all, I think that my colleagues should brush just as well. But even if I'm the only one, at least clients will be brushed five times a week.”

This factor was called motivated but aware of obstacles (Figure 4).

3.4 Factor 4: Concerned and insecure

Caregivers in this factor are aware of the consequences of poor oral care.

They disagree with statement 8: “I do not know the consequences of poor oral hygiene.” “I think I know indeed. That's also a motivation to do it right,” and “I think I know what the consequences are: decaying teeth, cavities, infections, smells.”

In addition, they agree with statement 36: “I know well enough how to brush someone's teeth.” “I think so, I may hope. That's what I have learned from the dentist.”

“My parents and my teachers in primary school taught me how to brush my teeth. I have learned brushing my clients’ teeth during my training and in practice.”

However, they are insecure about the way they brush their clients’ teeth.

Unlike in the other factors, this group agrees with statements 35: (“I find it difficult to brush someone else's teeth”) and 29 (“I'm afraid that I'm going to hurt the client during brushing.”). “I find it very difficult to reach everywhere. It's almost impossible to see everything, and even though I put my fingers in the mouth to keep the cheeks aside as well as I can, I still find it quite difficult and I'm not sure if I always brush as well as I would like.” Whereas factors 1, 2 and 3 are neutral, factor 4 disagrees with statement 40: “I'm doing the best I can but the dentist never thinks it's good enough.”

“When I'm doing the best I can, the dentist says ‘I did a good job. Some people are just difficult to clean, so it's a fact that not everyone's mouth is completely clean. But the moment you get the most out of it, the dentist will notice. And if you make a half-hearted attempt, he will see it too.”

Similar to caregivers in factor 1, people in factor 4 slightly agree with statement 19: “I brush the client's teeth as well as I do my own.” “Yes, I think I do. Why would I do it anything less?”

This attitude was called concerned and insecure (Figure 5).

4 DISCUSSION

This study revealed the prevailing viewpoints of caregivers of Institutionalized living persons with moderate intellectual disabilities in the Netherlands. On the basis of the results of this study, four factors could be identified: (i) responsible and perseverant, (ii) social minded and knowledgeable, (iii) motivated but aware of obstacles and (iv) concerned and insecure. Q-methodology was found to be a useful method for determining the different attitudes caregivers of people with moderate intellectual disabilities have regarding oral health care.

Unlike Dougall and Fiske (2008), we found that caregivers are not doubtful about their role in oral care. It appeared that they also dill not feel that brushing a client's teeth undermines the client's autonomy. A similarity with Dougall's research is that they sometimes find brushing someone else's teeth difficult. Compared to the earlier described results of Thole et al. (2010), the results of this study confirm their findings that the obstacle of clients not opening their mouth truly hampers the execution of daily oral care. However, the studies mentioned above did not use the Q-methodology.

Several studies regarding people with intellectual disabilities using Q-methodology have been conducted. Nevertheless, none of them have focused on dentistry. However, a study by Kreuger et al. (2008) of the needs of persons with severe intellectual disabilities found that physical well-being was most important for all clients. Although no specific statements on oral health care were included in this study, good oral health contributes to physical well-being.

The use of Q-methodology in dentistry is very limited. Witton et al. (2015) wrote an article regarding dentists’ attitudes towards prevention guidance. A study by Trubey et al. (2013) focused on attitudes of Community Dental Service staff towards developing a school-based toothbrushing programme. Davis et al. (2015) and Prabakaran et al. (2012) studied the motivations for orthodontic treatment. No studies on special care dentistry using Q-methodology are published. However, when the results of this study are compared with a comparable study by Vermaire et al. (2010) on parental attitudes towards oral health and the dental care of their children, some overlap can be found: most parents acknowledge their responsibility for their children's’ oral health. They also feel that healthy teeth are important for someone's appearance and thereby for their self-assurance. On the other hand, some are not confident that their effort will have the desired effect, and they note the barriers they encounter.

This study has several limitations that should be addressed when interpreting the results. First, it included opinions of caregivers of institutionalized persons with a moderate intellectual disability only. People with mild or profound intellectual disabilities may possibly present different behaviours towards the delivery of oral health care. This could affect the attitudes of the caregivers accordingly and therefore may hamper generalization to caregivers of other client groups.

Another limitation of this study is that this study included an overrepresentation of male caregivers compared to the total national population of caregivers in the Netherlands. Additionally, more people with a higher educational level participated at the expense of people with a lower education level. This could have influenced the outcomes. Finally, because this study was executed in the Netherlands, the external validity may be limited to countries with similar systems for providing (health) care to people with intellectual disabilities.

The aim of this study was to gain knowledge regarding different types of caregivers to tailor oral healthcare instructions. Knowing the type of caregiver could give oral health professionals better insight into the reasons why given advice is not followed, or can help him/her personalize the instructions. For example, there is no need to motivate caregivers with attitude 2 (motivated but aware of obstacles). More can likely be accomplished when oral care professionals provide them with adapted instructions to limit the obstacles in the caregivers’ experience. Caregivers with attitude 4 (concerned and insecure) will benefit more from a positive approach, such as letting them enrol in refresher courses or (e-learning) training modules rather than from an overabundance of information.

To investigate whether instructions given by dental care professionals indeed will be better apprehended when they are adapted to the caregivers’ specific factors will be a next step for further research. Another next step may be the development of a tool to determine factors or attitudes by which caregivers should be categorized. Asking caregivers about their opinions regarding the distinguishing statements could potentially improve this process.