Hospital admissions and place of death of residents of care homes receiving specialist healthcare services: A systematic review without meta-analysis

Deborah Buck and Sue Tucker are joint first authors.

Funding information

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Social Care Research (SSCR) (Funding reference number C088/CM/UMDC-P113: Effective Healthcare Support to Care Homes). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR SSCR or the Department of Health and Social Care, NIHR or NHS.

Abstract

Aim

To synthesize evidence on the ability of specialist care home support services to prevent hospital admission of older care home residents, including at end of life.

Design

Systematic review, without meta-analysis, with vote counting based on direction of effect.

Data sources

Fourteen electronic databases were searched from January 2010 to January 2019. Reference lists of identified reviews, study protocols and included documents were scrutinized for further studies.

Review methods

Papers on the provision of specialist care home support that addressed older, long-term care home residents’ physical health needs and provided comparative data on hospital admissions were included. Two reviewers undertook study selection and quality appraisal independently. Vote counting by direction of effect and binomial tests determined service effectiveness.

Results

Electronic searches identified 79 relevant references. Combined with 19 citations from an earlier review, this gave 98 individual references relating to 92 studies. Most were from the UK (22), USA (22) and Australia (19). Twenty studies were randomized controlled trials and six clinical controlled trials. The review suggested interventions addressing residents’ general health needs (p < .001), assessment and management services (p < .0001) and non-training initiatives involving medical staff (p < .0001) can reduce hospital admissions, while there was also promising evidence for services targeting residents at imminent risk of hospital entry or post-hospital discharge and training-only initiatives. End-of-life care services may enable residents to remain in the home at end of life (p < .001), but the high number of weak-rated studies undermined confidence in this result.

Conclusion

This review suggests specialist care home support services can reduce hospital admissions. More robust studies of services for residents at end of life are urgently needed.

Impact

The review addressed the policy imperative to reduce the avoidable hospital admission of older care home residents and provides important evidence to inform service design. The findings are of relevance to commissioners, providers and residents.

1 INTRODUCTION

The number of care homes in the UK (variously known as nursing homes or long-term care/residential/aged care/assisted living facilities in different countries) has declined in recent years. Nevertheless, over 400,000 older adults live in such facilities and despite the ongoing imperative to provide care at home, population ageing is likely to increase demand for care home beds in coming decades, a situation seen internationally (Deloitte Access Economics, 2020; Harris-Kojetin et al., 2019; Nuffield Trust, 2020).

Care home residents are typically frail with multiple physical and mental co-morbidities and subject to polypharmacy (BGS, 2016; Gordon et al., 2014; Russell, 2017). However, care homes often find it difficult to access timely and appropriate healthcare support for residents, resulting in the under-detection of potentially treatable conditions, increased hospital admissions and lack of resident choice about place of death (Iliffe et al., 2016; NSW Aged Care Roundtable, 2019; NHS England, 2015). Although hospital admission of older adults is sometimes appropriate, it is often associated with adverse effects including infection, delirium, confusion and falls (Agotnes et al., 2016; Arendts et al., 2017; McAndrew et al., 2016). It is thus concerning that up to two-fifths of emergency admissions of older care home residents could be managed in the care home or prevented with better care or vigilance (NHS, 2019; Wolters et al., 2019). Furthermore, although most care home residents would prefer to remain in the care home at end of life (Ennis et al., 2015; Finucane et al., 2013; Wiggins et al., 2019), around 30% die in hospital (Public Health England, 2017).

There is increasing policy attention given to this issue. The NHS Long-Term Plan acknowledged the need to improve care home support (NHS, 2019), while the ‘Framework for Enhanced Health in Care Homes’ highlighted the need for equivalent services to people at home. One service specification for primary care networks (groups of local general practices) relates to enhanced care for care homes and others are relevant, including structured medication reviews and anticipatory care (NHS England, 2020).

1.1 Background

Historically, a patchwork of specialist healthcare support services for care homes has emerged. For the purpose of this review, these are defined as services whereby healthcare professionals, with time dedicated to this role, provide specialist clinical support to identify and address residents’ healthcare needs (Tucker et al., 2019). Some enhance standard primary care, allocating named practitioners to specific care homes or supplementing medical care with specialist nurse input; others involve partnerships between primary and secondary care and some are led by pharmacists. Core activities include comprehensive assessment of new residents; regular, structured multidimensional reviews; falls prevention; medication reviews; advance care planning and end-of-life care.

Evidence of a relationship between the provision of specialist healthcare support services and reduced avoidable hospital admissions would provide a strong argument for their expansion. However, the extent to which current models achieve this is unclear. A previous review (Clarkson et al., 2018) explored the organization, activities and responsibilities of specialist healthcare support services, but did not systematically explore outcomes. Other reviews have explored the extent to which specific activities including optimizing prescribing (Alldred et al., 2016; Forsetlund et al., 2011; Thiruchelvam et al., 2017; Wallerstedt et al., 2014), antibiotic stewardship programmes (Feldstein et al., 2018) and palliative care initiatives (Hall et al., 2011) can reduce admissions. However, the quality of evidence in these and a review of interventions to reduce acute admissions of nursing home residents (Graverholt et al., 2014) were generally poor, while the heterogeneity of interventions, methods and outcomes in reviews of the effectiveness of input from staff with geriatric expertise, integrated and partnership working (Davies et al., 2011; Goldman, 2013; Santosaputri et al., 2018) precluded robust conclusions. As such, an overall picture of the evidence to inform service development is lacking.

In addressing this gap, this review employed two taxonomies (Table 1) developed from a UK survey of specialist healthcare support services (Hargreaves et al., 2019). The first has five categories, using constructs of specialist support identified in the care home literature (Clarkson et al., 2018). The second allocated services with similar characteristics into three subgroups using latent class analysis (Hargreaves et al., 2019).

| Taxonomy 1 (Clarkson et al., 2018) | Taxonomy 2 (Hargreaves et al., 2019) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Brief description | Category | Brief description |

| Assessment, no medical practitioner involvement | Provide assessment only. Advice and/or direct training may be given to care home staff and/or recommendations made to residents’ primary care physicians. No on-going management or support of individual care home residents or additional input from physicians (over usual care). | Predominantly direct care | High probability of scheduled input and support for all residents. Moderate probability of medication management. Low probability of staff training. |

| Assessment, (additional) medical practitioner involvement | Assessment only as above, but additional input from physicians (over usual care). | Predominantly indirect care | Low probability of scheduled input and support for all residents and medication management. High probability of staff training. |

| Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | Provides assessment and on-going management of the health/care of residents (potentially including prescribing). No additional input from physicians (over usual care). Advice and/or direct training may be given to care home staff. | Direct and indirect care | Moderate-to-high probability of scheduled input, support for all residents, medication management and staff training. |

| Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Assessment and management as above, including additional input from physicians (over usual care). | ||

| Training and support | Support provided to the home, not individual residents. This may include training for care home staff and/or assistance with quality improvement initiatives. However, the team do not assess or see individual residents. | ||

2 THE REVIEW

2.1 Aims

The primary aim was to identify, appraise and synthesize the evidence on the ability of specialist healthcare support services to: (1) reduce hospital admissions of older care home residents and (2) enable them to remain in the care home at end of life. Secondary aims were to: (3) determine whether particular service subgroups produced different outcomes; (4) explore how usual/standard care was defined and (5) identify service costs.

2.2 Design

A systematic review, without meta-analysis, with vote counting based on direction of effect updated and extended the review by Clarkson et al. (2018) in seeking studies published post 2010 and appraising outcomes. The review followed established guidance (CRD, 2009; Rutter et al., 2010) and the protocol was registered (PROSPERO) and published (Tucker et al., 2019). Reporting used the SWiM reporting guideline (Campbell et al., 2020) in conjunction with the 2020 PRISMA checklist (Page et al., 2021) to promote transparency.

2.3 Search methods

Searches were conducted in 14 electronic databases: AgeInfo, CINAHL Plus, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews and Effectiveness, EMBASE (incorporating Medline), the Health Technology Assessment Database, Health Management Information Consortium, the Joanna Briggs Foundation, the National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database, PsycINFO, PubMed, PROSPERO, Social Care Online and Web of Science. Initial searches were undertaken in November 2017 and auto-alerts monitored until January 2019. Reference lists of identified reviews, included documents and study protocols, were scrutinized for further studies.

Four search blocks (endorsed by a research librarian) were combined in EMBASE and adjusted for other databases. These pertained to: (1) care homes; (2) healthcare; (3) older people and (4) hospital admission and place of death. An example search strategy for EMBASE is given in Supplementary Appendix S1. No geographical limitations were imposed, but non-English language publications were excluded.

2.4 Study selection and quality appraisal

Two reviewers (DB and ST) independently screened the results against the study inclusion/exclusion criteria (Box 1) and quality appraised inclusions using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool (Armijo-Olivo et al., 2012; Thomas et al., 2004). This is suitable for quantitative studies and covers six domains (selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection and withdrawals/dropouts), each of which is rated strong, moderate or weak. A global rating is allocated depending on the number of weak ratings – strong (none), moderate (one) or weak (two plus) (Armijo-Olivo et al., 2012; Jackson & Waters, 2005; Thomas et al., 2004). Given the largely objective nature of the primary outcomes (raising fewer problems with reliability/validity than, say, clinical assessments), sections concerning the blinding of outcome assessors and data collection were adapted. (The modified tool is available from the authors.)

BOX 1. Review Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies

Included: Empirical research studies and service descriptions published in peer-reviewed journals, in English language, that provided comparative quantitative data on the primary outcomes.

Excluded: Commentaries, opinion pieces and descriptive articles lacking empirical data; and studies not published in English language.

Settings

Included: Care homes for older people with or without nursing, including facilities for older people with dementia.

Excluded: Studies concerned solely with the delivery of care in hospital, individuals’ own homes or other community settings.

Participants

Included: Older people, with or without dementia, permanently resident in care homes. Specifically, people aged 60 or over, samples with a mean/median age of 69 plus where age is reported, and samples described as samples of older people where age is not reported.

Excluded: Studies concerned only with the provision of support for younger or short-stay residents.

Interventions

Included: Studies of specialist services specifically designed to address the physical healthcare needs of older long-stay care home residents, including organizational or multi-faceted interventions with this goal.

Excluded: Services/interventions designed to address care home residents’ mental health or social care needs, including those focused on the provision of person-centred care.

Outcomes

Included: Studies that reported information on ED transfers, hospital admissions (all admissions, emergency admissions, planned admissions and/or readmissions) and/or place of resident death.

Excluded: Studies that lacked relevant outcome data or which retrospectively explored associations in large administrative datasets (rather than evaluating particular services/interventions).

2.5 Data extraction

One reviewer extracted data on study ID, aims, design, methods, participants, interventions/services, comparison interventions/services, outcomes and costs using a specially designed Excel form. A second reviewer checked all extracted data for accuracy, consistency and agreement. Disagreements or uncertainties were resolved through discussion with the wider research group. The form was tested and refined by the same two reviewers and agreed by the review team before full data extraction. Where multiple reports were identified from the same study, information was extracted from each publication separately but combined into one study record for the purpose of synthesis.

2.6 Data synthesis

The key characteristics and results of each study were charted, described and synthesized according to the primary outcomes. No studies were discarded because of their quality rating, but weak-rated studies are highlighted in the text with the superscript*. Only studies that explicitly aimed to reduce hospitalization were included in effectiveness analyses.

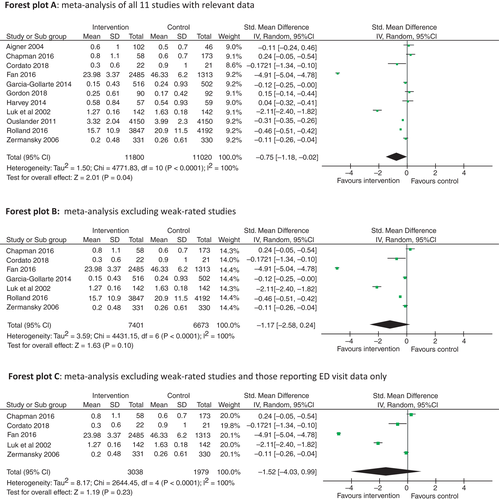

A random-effects model meta-analysis (Borenstein et al., 2010) was attempted to estimate the effect size of specialist healthcare support interventions on hospitalizations. The analysis was conducted in Review Manager 5.4 (2020) and included 11 studies that reported the intervention and control group sample sizes and mean and standard deviation of hospital admissions/ED transfers post-intervention. Forest plots were presented to visualize the results. Sensitivity analyses explored the effects of study quality (excluding weak-rated studies) and outcome domains (excluding data on ED transfers).

Given the diversity of interventions, variation in effect measures and high level of missing/incomplete outcome estimates, vote counting based on direction of effect (regardless of statistical significance or testing) was used to detect evidence of an effect for study subgroups according to the foci of intervention and two taxonomies (McKenzie & Brennan, 2019). All studies reporting a positive effect on the number and/or rate of hospital admissions/ED transfers were considered beneficial regardless of any co-existing negative effects so as not to penalize studies reporting multiple outcomes. Studies reporting no change were classed as ‘no positive outcome/not beneficial’; studies reporting practitioners’ perceptions of avoided admissions or only hospital bed days were excluded. Binomial tests assessed statistical significance of the vote counting findings (McKenzie & Brennan, 2019) and sensitivity analysis explored the effect of treating studies with mixed findings as negative (reversing their handling in the main analysis). Correction for multiple testing was undertaken using the conservative Bonferroni method of multiplying the p-values by the number of comparisons (Jafari & Ansari-Pour, 2019) in cases where there appeared to be a significant outcome. This was applied to each subset of analyses, that is, considering foci of intervention as one set (six comparisons), and the models of specialist support, namely Taxonomy 1 and Taxonomy 2, as two further sets (five and three comparisons respectively).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Search outcomes

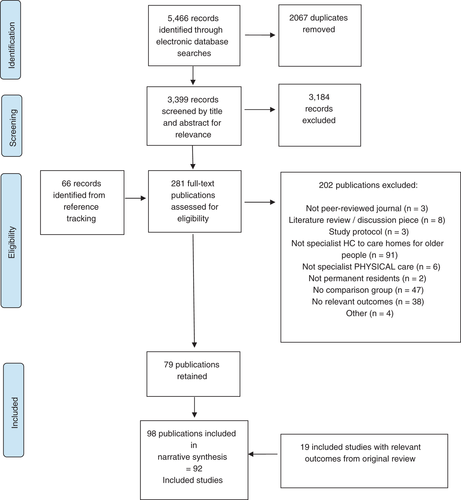

Electronic database searches identified 5466 references (Figure 1). After duplicates were removed, 3399 records were screened by title and abstract for relevance and the full texts of the 215 remaining documents, plus 66 citations identified by reference tracking, were independently assessed against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. This resulted in 92 included studies (98 references): 79 from the searches plus 19 from the review by Clarkson et al. (2018).

3.2 Study characteristics

Of the 92 included studies, 22 were undertaken in the UK, 22 in the USA and 19 in Australia (Tables 2 and 3). The earliest was published in 1991, but most (n = 82) were published between 2010 and 2019. Supplementary Appendix S2 provides more detail.

|

Author, year (Country) |

Study designa | Setting and Participants | Taxonomy 1 | Taxonomy 2 | Disciplinesb | Main results |

EPHPP Quality ratingc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interventions to improve residents’ general physical health | |||||||

|

Ackerman and Kemle (1998) (USA) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 1 nursing home: 92 beds (250 residents, 298 admissions relating to 142 residents) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Gerontologist physician assistant | There was a significant reduction in annual admissions per 1000 patient years: p = .03 | Weak |

|

Aigner et al., (2004) (USA) |

Other (two-group observational cohort) | 8 nursing homes: 203 residents of whom 148 included in admission analysis (IG 102, CG 46) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Nurse practitioners, physicians |

The mean number of admissions per resident per year was higher in the IG than CG but the difference was not significant: p = .99 The % of residents with at least one admission was lower in the IG than CG but the difference was not significant: p = .85 |

Weak |

|

Arendts et al. (2018) (Australia) |

Controlled clinical trial | 6 residential assisted care facilities: 200 residents (IG 101, CG 99) | Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Nurse practitioners | Rates of ED visits and risk of admission were lower in the IG than CG but the differences were not significant: ED visits p = .36, risk of admissions p = .10 | Moderate |

|

Bellantonio et al. (2008) (USA) |

Randomized controlled trial | 2 dementia-specific assisted living facilities: 100 older adults with dementia (IG 48, CG 52) | Assessment, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Geriatrician, advanced practice nurse, physical therapist, dietician, medical social worker | ED visits and admissions decreased but there was no significant difference between the IG and CG: ED visits p = .80, admissions p = .13 | Moderate |

|

Boorsma et al. (2011) (The Netherlands) |

Randomized controlled trial | 10 residential care facilities: 340 residents (IG 201, CG 139) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Multiple disciplines including geriatrician, psychologist | A higher proportion of IG than CG residents were admitted to hospital but the difference was not significant: p = .11 | Moderate |

|

Boyd et al. (2014) (New Zealand) |

Controlled clinical trial | 54 residential assisted care facilities: 2553 residents/beds (IG 1425, CG 1128) | Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly indirect | Specialist gerontology nurse | Admissions increased in both groups, but the increase was significantly less in the IG than the CG: p < .001 | Moderate |

|

Burl and Bonner (1991) (USA) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 3 nursing homes: 118 cases (IG NR, CG NR) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Geriatric nurse practitioner, medical director | There were non-significant reductions in ED visits and overall admissions (p values NR) | Weak |

|

Burl et al. (1998) (USA) |

Other (two-group observational cohort) | 45 long-term care facilities: 1077 residents (IG 414, CG 663) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Geriatric nurses, medical directors | The IG had significantly fewer hospital bed days per 1000 residents than the CG: p = .008 | Weak |

|

Bynum et al. (2011) (USA) |

Other (two-group observational cohort) | 4 continuing care retirement community sites: 2468 residents: (IG 599 residents, 42 NH beds, CG 1909 residents, 186 NH beds) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Nurse practitioners, physicians | The IG had a significantly lower admission rate per 100 person years than the CG: p < .001 | Weak |

|

Codde et al. (2010) (Australia) |

Other (combination of two-group and one group pre +post cohort) | 30 residential assisted care facilities: 2352 ED transfers (IG 661, CG1 801, CG2 456, CG3 434) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | ED-based nurses, general practitioners |

There was a small reduction in admissions but this was not significant: p = .65 There was a significant reduction in ED transfers in the pre +post analysis: p = .01 |

Weak |

| Randomized controlled trial | 36 residential assisted care facilities: 1998 residents (IG 1123, CG 875) | Assessment and management. medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Gerontology nurse specialist, geriatrician, pharmacist |

All admissions and admissions for ambulatory sensitive care conditions were higher in the IG than the CG but the differences were not significant: all admissions p = .84, ASCC admissions p = .16 Significantly less IG residents with five pre-specified diagnoses were admitted to hospital: p = .043 |

Moderate | |

|

Connolly et al. (2018) (New Zealand) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 21 long-term care facilities; 1296 beds (IG 1296, CG 1296) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Gerontology nurse specialist, geriatrician, pharmacist | There was a significant reduction in ED presentations: p < .001 | Strong |

|

El-Masri et al. (2015) (Canada) |

Other (three-group observational cohort) | 4 care homes: 1353 cases, 311 residents (IG 374, CG1 636, CG2 343) | Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Nurse practitioner | The rate of ED transfers by nurse practitioners was slightly higher than that by Medical Directors but the difference was not significant: Odds ratio 1.04, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.99 | Weak |

|

Gordon et al. (2018) (UK) |

Other (three-group observational cohort) | 12 care homes with and without nursing: 239 residents (IG 90, CG1 92, CG2 57) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Disciplines varied between sites but included nurses and/or general practitioners | Mean admissions and ED visits were higher in the IG than CGs but not significantly so: admissions IG vs. CG1 p = .61, IG vs. CG2 p = .22; ED visits IG vs. CG1 p = .61, IG vs. CG2 p = .43 | Weak |

|

Hex et al. (2015) (England) |

Cohort analytic (two-group pre +post) | 48 care homes: 1444 residents (IG 942, CG 502) | Assessment, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Doctors, nurses | ED visits and avoidable hospital admissions fell more in the IG than the CG but there was no statistical testing | Weak |

|

Hui et al. (2001) Hui and Woo (2002) (Hong Kong) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 1 nursing home: 200 beds | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Geriatrician, psycho-geriatrician, nurse specialist, podiatrist physiotherapist, occupational therapist, dermatologist | ED visits and hospital admissions decreased but there was no statistical testing | Weak |

|

Joseph and Boult (1998) (USA) |

Other (one group, descriptive study with comparator being other published data) | 30 nursing homes in IG: 307 residents in IG | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Geriatricians, nurse practitioners | The IG residents had a lower number of hospital days per 1000 residents than reported in other studies but there was no statistical testing | Weak |

| Other (three-group observational cohort) | 88 nursing homes: 4804 residents (average per month IG 1936, CG1 1123, CG2 1745) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Nurse practitioners, primary care physicians | All and preventable admissions decreased significantly: p < .001 | Moderate | |

|

Klaasen et al. (2009) (Canada) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 1 care home: 116 beds (IG 116, CG 116) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Nurse practitioner, medical director | ED transfers decreased but there was no statistical testing | Weak |

|

Lacny et al. (2016) (Canada) |

Cohort analytic (three-group pre +post) | 2 nursing homes: 518 residents of whom 180 were included in the analysis (IG 45, CG1 65, CG2 70) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Multiple disciplines including nurse practitioner, family physicians | IG ED transfer rates increased less than the internal and combined CGs and more than the external CG but none of the differences were significant: IG vs. internal CG p = .97, IG vs. external CG p = .45, IG vs. combined CG p = .70 | Weak |

|

Lisk et al. (2012) (UK) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 6 nursing homes: number of residents NR | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Consultant geriatricians, pharmacists | There was a significant decrease in the average number of admissions: p = .002 | Weak |

|

Luk et al. (2002) (Hong Kong) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 14 private old age homes: 316 residents of whom 142 were included in the analysis (IG 142, CG 142) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Multiple disciplines including geriatric health nurses, geriatricians | There were significant decreases in mean ED attendances and acute admissions per person: p < .05 | Moderate |

|

Pain et al. (2014) (Australia) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 1 residential assisted care facility: number of residents NR | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | General practitioner | The number of ED presentations decreased but there was no statistical testing | Weak |

|

McAiney et al. (2008) (Canada) |

Other (one group, descriptive study with the comparator ‘perceived avoided admissions’) | 22 care homes: 2315 client contacts | Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Nurse practitioners | Nurse practitioners considered admission was prevented in 43% of cases | Weak |

|

Ono et al. (2015) (Japan) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 1 nursing home: 479 hospital admissions (IG 219, CG 260) | Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Nurse practitioner | A significantly lower % of IG than CG residents were transferred to hospital by ambulance and admitted: ambulance transfers: p = .006, admissions p < .001 | Weak |

|

Ouslander et al. (2011) (USA) |

Cohort analytic (two-group pre +post) | 30 nursing homes: number of residents NR (but estimate at least 4150) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Gerontological nurse practitioner |

There were significantly fewer admissions per 1000 residents in the IG than CG1: p = .02 The hospitalization rate per 1000 resident days fell more in the IG than in CG2 but this was not significant: p = .12 |

Weak |

|

Rolland et al. (2016) Cool et al. (2018) (France) |

Controlled clinical trial | Rolland et al., 175 nursing homes: 8039 residents (IG n = 3847, CG 4192); Cool et al., 159 nursing homes included in the analysis: 629 residents (IG 290, CG 339) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Geriatrician |

The rate of ED transfers decreased significantly in the IG and increased significantly in the CG. Within-group change: IG p = .004, CG p = .02 A significantly smaller proportion of IG than CG residents were admitted to hospital: p = .02 |

Moderate |

|

Salles et al. (2017) (France) |

Other (one group retrospective descriptive study with the comparator what general practitioners would have done without the service) | 39 nursing homes: 304 residents, 500 telemedicine acts | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Geriatrician, psychiatrist, rehabilitation physician, specialist nurses | GPs judged that without the telemedicine service, they would have arranged admission in 61/500 instances and ED transfer in 4 more | Weak |

|

Sankaran et al. (2010) (New Zealand) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 1 aged-related residential care facility: 96 beds (IG 64 with medication reviews, CG all residents from 96 beds) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Geriatrician, clinical nurse specialists, social worker | All admissions decreased but the change was not significant (p value NR) | Weak |

|

Street et al. (2015) (Australia) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | Number of residential assisted care facilities NR: 4329 ED presentations (IG 2051, CG 2278) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Specialist practice nurses, geriatrician | ED presentations and hospital admissions decreased significantly: p < .001 | Moderate |

|

Wade et al. (2015) (Australia) |

Other (one group, descriptive study with the comparator ‘perceived avoided admissions’) | 3 residential assisted care facilities: 40 video consultations | Assessment, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | General practitioners | General practitioners considered 3/40 video consultations prevented hospital attendance | Weak |

|

Winstanley and Brennan (2007) (England) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 4 care homes (residential and nursing): 142 residents (IG 142, CG 142) | Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Nurse clinician, pharmacist | Emergency admissions and mean admissions per month were lower in the IG than the CG but there was no statistical testing | Moderate |

| Interventions for acutely unwell residents | |||||||

|

Bandurchin et al. (2011) (Canada) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 7 care homes: number of residents NR | Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Nurse | Ambulance transfers to EDs decreased but there was no statistical testing | Weak |

|

Chan et al. (2018) (Australia) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 12 nursing homes: 4963 ED transfer episodes (IG 2348, CG 2615) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Geriatricians, nurse | There was a significant reduction in ED presentations by ambulance: p = .001 | Strong |

|

Crilly et al. (2010) (Australia) |

Other (two-group observational cohort) | Number of assisted care facilities NR: 177 residents (IG 62, CG 115) | Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Nurses | The rate of hospital readmission was exactly the same in the IG and CG: p = .99 | Moderate |

|

Fan et al. (2016) (Australia) |

Cohort analytic (two-group pre +post) | Number of residential assisted care facilities NR: 3048 beds pre-intervention (CG1 2127, CG2 921); 3798 beds post-intervention (IG1 2485, CG3 1313) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Unclear but included an ED nurse and medical staff | The IG had a significantly lower rate of ED presentations and admissions via ED per 1000 beds at 3 and 12 months: p < .0001 | Strong |

|

Grabowski and O'Malley (2014) (USA) |

Cohort analytic (two-group pre +post) | 11 nursing homes: 1767 beds (IG 1067, CG 700) | Assessment, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Registered nurse, nurse practitioner, physician | The hospital admission rate fell more in the IG than the CG but the difference was not significant (p value NR) | Weak |

|

Hofmeyer et al. (2016) (USA) |

Other (one group, descriptive study with the comparator ‘perceived avoided admissions’) | 20 long-term care facilities: 736 two-way video transfer consultations and 863 other telephonic encounters | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Multiple disciplines including advanced practice providers, registered nurses, physicians, pharmacists | Skilled providers considered 511 potential hospital transfers were avoided | Weak |

|

Hullick et al. (2016) (Australia) |

Cohort analytic (two-group pre +post) | 12 residential assisted care facilities: 775 annual individual patients pre-intervention, 418 post (IG 360 pre, 172 post, CG 415 pre, 246 post) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Nurses including an ED advanced practice nurse |

The odds of hospital admission increased in both groups, but significantly less in the IG, p = .0012 The odds of re-admission decreased more in the CG than the IG, but the difference was not significant, p = .49 |

Strong |

|

Hutchinson et al. (2015) (Australia) |

Interrupted time series |

73 residential care facilities: 1327 residents (IG 1327; CG NR) |

Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Aged care nurse specialists, geriatricians | There was a significant decrease in mean inpatient admissions per patient: p = .046 | Strong |

|

Ingber et al. (2017) Rantz, Popejoy, et al. (2017)); Rantz, Birtley, et al. (2017)) (USA, 7 linked initiatives) |

Other (two-group observational cohort) | 405 nursing facilities: 61,636 residents (IG 22,442, CG 39,194) | 4 × Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement; 1 × Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement; 2 × training and support | 5 × Direct and indirect; 2 × predominantly indirect | Advanced practice nurses at all sites, consultants at some sites, pharmacists at some sites | There were significant reductions in all-cause and potentially avoidable hospitalizations in five states, all-cause hospitalizations in another and no significant change in the seventh (p values NR) | Moderate |

|

Jensen et al. (2016) (Canada) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 10 long-term care facilities: 911 calls for 360 cases (IG 224, CG 136) | Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Extended care paramedics |

The % of residents admitted to hospital as an emergency was lower in the IG than the CG but not significantly so (p value NR) The % of IG residents transported to the ED was significantly lower than the CG: p < .001 |

Weak |

|

Mason et al. (2012) (UK) |

Other (two-group observational cohort) | Number of care homes NR: 456 residents (IG 259, CG 197) | Assessment, no medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Emergency care practitioners | Significantly fewer IG than CG residents were referred to hospital: difference −64.9%, 95% CI −71.8% to −58.0% | Weak |

|

Montalto (2001) (Australia) |

Other (one group, descriptive study with comparator ‘implied avoided admissions’ due to ‘hospital in the home unit’) | Number of supported residential facilities (mostly nursing homes for people with dementia) NR: number of residents NR | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Medical and nursing staff | There were 28 admissions to the HHU, implying 28 avoided hospital admissions | Weak |

|

Shah et al. (2015) (USA) |

Cohort analytic (two-group pre +post) | 21 senior living communities: 1537 residents (IG 479, CG 1058) | Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Telemedicine assistant |

ED transfers for ambulatory sensitive care conditions fell significantly in the post- vs. pre-IG: Rate ratio 0.661, 95% CI 0.444 to 0.982 ED use for ambulatory sensitive care conditions decreased in the IG and was stable in the CG but the difference was not significant: p = 0622 |

Moderate |

|

Tena-Nelson et al. (2012) (USA) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 30 nursing homes of which 18 included in the admissions analysis: number of residents NR but estimate 6750+) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Unclear | Hospital admissions reduced, but not significantly so: p = .332 | Weak |

|

Unroe et al. (2018) (USA) |

Other (two-group observational cohort) | 44 nursing facilities: 1286 billed episodes (IG 630, CG 656) | Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Nurse practitioner | The percentage of residents transferred to hospital was the same in both groups and there was no statistical testing | Weak |

| Interventions for residents at the end of life | |||||||

|

Agar et al. (2017) (Australia) |

Randomized controlled trial | 20 nursing homes: 131 resident deaths (IG 67, CG 64) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Nurse trained as palliative care coordinator | A slightly higher percentage of IG than CG residents were admitted to hospital in the last month of life but the difference was not significant (p value NR) | Moderate |

|

Chapman et al. (2018) (Australia) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 4 residential care facilities: 277 residents (IG 104, CG 173) | Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Palliative care nurse practitioner | There was a non-significant increase in the mean number of admissions prior to end of life: p = .71, decedents only | Moderate |

|

Garden et al. (2016) (England) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 7 care homes: 107 residents with dementia (IG 107, CG 107) | Assessment, medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Nurses, consultant psychiatrist | Admissions decreased post-intervention but there was no statistical testing | Weak |

|

Hockley et al. (2010) (Scotland) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 7 nursing homes: 248 residents who died (IG 133, CG 95) | Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Palliative care nurse | Slightly more IG than CG residents were admitted in the last 8 weeks of life but there was no statistical testing | Moderate |

|

Kinley et al. (2018) (UK) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 1 nursing home: 14 residents: (IG 14, CG 14) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Unclear | The number of admissions decreased but there was no statistical testing | Weak |

|

Kuhn and Forrest (2012) (USA) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 2 nursing homes: 31 residents with dementia (IG 31, CG 31) | Assessment, medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Hospice physicians, project nurse | The overall % of residents admitted to hospital increased but there was no statistical testing | Weak |

|

Kunte et al. (2017) (USA) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 2 long-term care facilities: 139 residents (IG 139, CG 139) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Unclear (end-of-life nursing education consortium) | The number of transfers to hospital / the ED decreased but there was no statistical testing | Weak |

|

Luk and Chan (2017) (Hong Kong) |

Other (two-group observational cohort) | 2 care and attention homes: number of residents NR | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Community geriatric assessment team, including physicians and nurses | The IG had a lower number of ED attendances and admissions than the CG in the 180 days before death but there was no statistical testing | Weak |

|

Moore et al. (2017) (England) |

Unclear | Number of nursing homes NR (2 in IG): 61 residents with advanced dementia (IG 9, CG 52) | Assessment, no medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | NR but multiple health disciplines led by an interdisciplinary care leader | The median number of hospital admissions in the previous month was lower in the IG than the CG but there was no statistical testing | Weak |

|

O'Sullivan et al. (2016) (Southern Ireland) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 3 nursing homes: 301 beds (IG 301, CG 287) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Unclear | There was a significant decrease in the admission rate: p < .001 | Weak |

|

Teo et al. (2014) (Singapore) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 7 voluntary welfare nursing homes: 293 residents (IG 96, of whom 48 decedents included in main analysis, CG 197) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Hospital nurses, physicians | The mean number of hospitalization episodes in the last 3 months of life was lower in the IG than the CG but there was no statistical testing | Weak |

| Interventions to improve prescribing | |||||||

|

Furniss et al. (2000) (England) |

Randomized controlled trial | 14 nursing homes: 330 residents (IG 158, CG 172) | Assessment, no medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Pharmacist | Inpatient days per resident decreased more in the IG than the CG but there was no statistical testing | Moderate |

|

Garcia-Gollarte et al. (2014) (Spain) |

Randomized controlled trial | 37 nursing homes: 1018 residents (IG 516, CG 502) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Expert nursing home physician | There was a non-significant increase in mean ED visits in the IG and a significant increase in the CG: IG p = .179, CG p = .022 | Moderate |

|

Lapane, Hughes, Christian, et al. (2011) (USA) |

Cohort analytic (two-group pre +post) | 26 nursing homes: 3462 residents (estimate IG 1824, CG 1638) | Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Pharmacist |

Mean hospitalizations increased less in the IG than the CG but there was no statistical testing Mean potential adverse drug event-related admissions fell in the IG and increased in the CG but the difference was not significant: adjusted hazard ratio 1.01; 95% CI 0.84 to 1.21 |

Strong |

|

Lapane, Hughes, Daiello, et al. (2011) (USA) |

Controlled clinical trial | 25 nursing homes: 3202 residents in 2003, 3321 in 2004 (IG 1711 and 1769, CG 1491 and 1552) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Pharmacists |

The mean level of hospitalizations of the target residents in both groups increased, but less so in the CG. There was no statistical testing The incidence rate per 1000 resident-months was higher in the IG than the CG but this was not significant (adjusted hazard ratio 1.11 [95% CI 0.94–1.31]) |

Strong |

|

McKee et al. (2016) (Northern Ireland) |

Other (rolling pre +post) | 16 nursing homes: number of residents NR | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Pharmacist, geriatrician | The average number of admissions from participating homes decreased, but there was no statistical testing | Weak |

|

Olsson et al. (2010) (Sweden) |

Cohort analytic (two-group pre +post) | 8 nursing homes: 302 residents (IG 135, CG 167) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Physicians | The percentage of residents admitted and number of admissions per resident were lower in the IG than in the CG, but there was no statistical testing | Moderate |

|

Pitkälä et al. (2014) (Finland) |

Randomized controlled trial | 20 wards in assisted living facilities: 227 residents (IG 118, CG 109) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Unclear (training provided by study authors) | The IG had significantly fewer days in hospital per year than the CG: p < .001 | Strong |

|

Potter et al. (2016) (Australia) |

Randomized controlled trial | 4 residential assisted care facilities: 95 residents (IG 47, CG 48) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Study general practitioner, study geriatrician/clinical pharmacologist | There were slightly fewer unplanned hospital admissions in the IG than the CG but the difference was not significant: p = .99 | Weak |

|

Roberts et al. (2001) (Australia) |

Randomized controlled trial | 52 nursing homes: 3230 residents (IG 905, CG 2325) | Assessment, medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Pharmacist, geriatrician, research nurse | The % change ([post-intervention minus baseline]/baseline) increased slightly in the IG, and decreased in the CG, but the changes were not significant | Moderate |

|

Zermansky et al. (2006) (England) |

Randomized controlled trial | 65 nursing and care homes: 661 residents (IG 331, CG 330) | Assessment, no medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Pharmacist |

The hospitalization rate decreased in the IG and increased in the CG but the difference was not significant: p = .11 The percentage of residents admitted fell more in the IG than CG but the difference was not significant: p = .62 |

Moderate |

| Post-hospital discharge interventions | |||||||

|

Cordato et al. (2018) (Australia) |

Randomized controlled trial | 21 nursing homes: 43 residents (IG 22, CG 21) | Assessment, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Geriatrician, nurse practitioner | The mean hospital re-admission rate was significantly lower in the IG than the CG: p = .03 | Moderate |

|

Gregersen et al. (2011) (Denmark) |

Other (combination of one group pre +post cohort and two-group observational cohort) | Number of nursing homes NR: 238 residents: (IG 153, CG 85) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Physician, physiotherapist, nurse | The IG had a significantly lower rate of non-elective re-admissions than the CG in the two-group analysis: adjusted estimate odds ratio 0.47, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.94 | Moderate |

|

Harvey et al. (2014) (Australia) |

Randomized controlled trial | 45 residential care facilities: 116 residents (IG 57, CG 59) | Assessment and management medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Geriatrician, aged care nurse consultant |

Overall and acute mean readmissions were higher in the IG than the CG but not significantly so: p = .80 and p = .60; Sub-acute mean readmissions were lower in the IG than the CG but not significantly so: p = .60 |

Weak |

|

Pedersen et al. (2016) (Denmark) |

Randomized controlled trial | 357 of 1330 patients were nursing home residents (IG 175/693; CG 182/637) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Nurses and doctors from geriatric team | The IG had a significantly lower rate of hospital readmissions than the CG: p < 0.001 | Moderate |

|

Pedersen et al. (2018) (Denmark) |

Randomized controlled trial | 52 nursing homes: 648 residents with one of nine specified medical diagnoses (IG 330, CG 318) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Nurses and doctors from geriatric team | The IG had significantly fewer readmissions to hospital or the hospital at home service than the CG: adjusted hazard ratio 0.63, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.95 | Strong |

|

Schubert et al. (2016) (USA) |

Cohort analytic (two-group pre +post) | 256 veterans but number in assisted living facilities NR (IG 179, CG 77) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Nurse practitioner, social worker, mental health liaison, geriatrician, pharmacist, psychologist | ED attendances and readmissions fell more in the IG than the CG but not significantly so: ED visits p = .59, readmissions p = .19 | Weak |

| Other specialist initiatives (specific focus noted after country) | |||||||

|

Beck et al. (2016) (Denmark) Nutrition |

Controlled clinical trial | 2 nursing homes: 31 residents (IG 9, CG 22) | Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Multiple disciplines including nutrition coordinator, dietician, physiotherapist, occupational therapist | A higher % of IG than CG residents were admitted but the difference was not significant: p = .498 | Moderate |

|

Brownhill (2013) (England) Falls prevention, pressure ulcer care, continence |

One group cohort (pre +post) | Number of nursing homes NR (estimate 24): Number of residents NR | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Unclear (but including nurses) | The number of residents admitted decreased but there was no statistical testing | Moderate |

|

Hutt et al. (2011) (USA) Care of residents with pneumonia |

Cohort analytic (two-group pre +post) | 16 nursing homes: 1123 residents (IG 549, CG 574) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Pharmacists, geriatrician, study liaison nurses |

The overall hospitalization rate fell in the IG and rose in the CG but neither change was significant: IG p = .55, CG p = 1.00 Inappropriate admissions rose in the IG and fell in the CG but neither change was significant: IG p NR, CG p = .67 |

Strong |

|

Mulrow et al. (1994) (USA) Physical therapy |

Randomized controlled trial | 9 nursing homes: 194 residents: (IG 97, CG 97) | Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Physical therapists | Hospitalization numbers were the same in the IG and CG; no statistical testing | Strong |

|

Romøren et al. (2017) (Norway) Intravenous fluids/antibiotics |

Controlled clinical trial | 30 nursing homes: 330 cases (IG 228, CG 102) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Nurses | There were significantly fewer potentially avoidable admissions in the IG than the CG: p < .01 | Moderate |

|

Sackley et al. (2016) (England and Wales) Occupational therapy |

Randomized controlled trial | 228 nursing and residential homes: 1042 residents who had a stroke or TIA (IG 568, CG 474) | Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Occupational therapists/assistants | The mean number of ED presentations per resident and % of residents admitted were the same in the IG and CG: ED presentations mean difference 0, 95% CI −0.07 to 0.06, admissions no statistical testing | Moderate |

|

Stern et al. (2014) (Canada) Wound care |

Randomized controlled trial | 12 long-term care facilities: 137 residents (IG 101 including 44 carried over from CG; CG 80) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Advanced practice nurses, chiropodist, occupational therapist, plastic surgeon | Estimated mean ED attendance and hospitalization rates were higher in the intervention than the control period but the differences were not significant: ED visits p = .52, hospitalizations p = .59 | Moderate |

|

Walker et al. (2016) (England) Falls prevention |

Randomized controlled trial | 6 residential and nursing homes for older people and people with learning disabilities: 52 residents (IG 25, CG 27) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Unclear but falls clinical specialists | There was no difference between the median number of admissions in the IG and CG: difference 0.0, 95% CI −0.8 to 0.8 | Weak |

|

Ward et al. (2010) (Australia) Falls prevention |

Randomized controlled trial | 88 residential assisted care facilities: 5391 residents (IG 2802, CG 2589) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Project nurse | The mean number of admissions per month following hip fracture/fall rose in the IG and fell in the CG but there was no statistical testing | Strong |

- Grey shading indicates those studies for which reducing hospital admissions was not a specific aim.

- NR, Not reported; IG, intervention group; CG, control group.

- a From the EPHPP.

- b Additional staff input over and above the comparator.

- c The blinding and data collection sections of the quality appraisal tool were adapted to reflect the fact that while hospitalization is a tangible event, there were sometimes uncertainties about the robustness of the data collection methods. However, this may have resulted in some studies being given a lower global rating than would otherwise have been the case.

|

Author and year (Country) |

Study designa | Setting and Participants | Taxonomy 1 | Taxonomy 2 | Disciplinesb | Main results |

EPHPP Quality ratingc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Agar et al. (2017) (Australia) |

Randomized controlled trial | 20 nursing homes: 131 resident deaths (IG 67, CG 64) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Nurse trained as palliative care coordinator | There was no significant difference in the % of residents who died in hospital (p value NR) | Moderate |

|

Baron et al. (2015) (England) |

Cohort analytic (two-group pre +post) | 16 nursing homes of which 12 provided comparative outcome data: 991 beds (IG 773, CG 218) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Unclear (Advanced care planning practitioner) | There was a decrease in the % of hospital deaths in the majority of IG homes and an increase in the CG but there was no statistical testing | Weak |

|

Brannstrom et al. (2016) (Sweden) |

Cohort analytic (two-group pre +post) | 19 care homes: 837 resident deaths (IG 457, CG 380) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Unclear: (nurses and Liverpool Care Pathway train the trainer course staff) | The % of people dying outside the care home fell more in the IG than the CG but there was no statistical testing | Moderate |

|

Bynum et al. (2011) (USA) |

Other (two-group observational cohort) | 4 continuing care retirement community sites: 2468 residents: (IG 599 residents, 42 NH beds, CG 1909 residents, 186 NH beds) | Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly direct | Multiple disciplines: nurse practitioners, physicians | The IG had a significantly lower proportion of deaths in hospital: p = .004 | Weak |

|

Chapman et al. (2018) (Australia) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 4 residential care facilities: 277 residents (IG 104, CG 173) | Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Palliative care nurse practitioner | There was a significant decrease in hospital deaths in those decedents who received the full intervention: p = .04 | Moderate |

|

Covington (2013) (England) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 1 nursing homes: 119 resident deaths (IG max 119; CG max 27) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Unclear (Care home staff attended Gold Standards Framework workshops) | The % of residents who died outside the CH decreased but there was no statistical testing | Weak |

|

Cox et al. (2017) England |

Cohort analytic (two-group pre +post) | 12 nursing and non-nursing care homes: 654 beds (IG 351, CG 303) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Clinical nurse specialist, lecturer, researcher | The number of residents who died in hospital decreased more in the IG than the CG but there was no statistical testing | Weak |

|

Finucane et al. (2013) (Scotland) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 7 nursing homes: 265 residents who died: (IG 132, CG 133) | Assessment, no medical practitioner involvement | Predominantly indirect | Palliative care nurse specialists | The % of deaths in hospital was higher in the sustainability than the full intervention stage but there was no statistical testing | Moderate |

|

Hockley et al. (2010) (Scotland) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 7 nursing homes: 248 residents who died (IG 133, CG 95) | Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Palliative care nurse | A smaller % of IG than CG deaths occurred in hospital but there was no statistical testing | Moderate |

|

Hockley and Kinley (2016) (UK) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | The number of nursing homes ranged from 19 in 2007/8 to 76 in 2014/15: 12,345 cases (deaths) (IG 11,777, CG 568) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Unclear (Specialist nurses and End-of-life care facilitators) | The % of residents who died in the NH increased but there was no statistical testing | Weak |

|

Kinley et al. (2014) (England) |

Other (combination of randomized controlled trial and three-group pre +post study) | 38 nursing homes: 2444 resident deaths (IG1 703, CG1 805, CG2 936) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Unclear (nurses plus Gold Standards Framework for care homes facilitators) | The % of residents who died in the care home increased more in the IG and CG1 compared with CG2 but the difference was not significant: p = .092 | Moderate |

|

Kinley et al. (2018) (UK) |

Two-group observational cohort | 1 nursing home: 14 residents: (IG 8, CG 6) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Unclear | A higher proportion of IG than CG residents died in their preferred place but there was no statistical testing | Weak |

|

O'Sullivan et al. (2016) (Southern Ireland) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 3 nursing homes: 301 beds (IG 301, CG 287) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Unclear | There was a significant decrease in the average % of deaths in hospital: p = .001 | Weak |

|

Reymond et al. (2011) (Australia) |

Other (combination of two-group and one group pre +post cohort) | 7 residential assisted care facilities: 299 cases (deaths) (IG1 253 post-intervention, CG1 46 pre intervention, IG2 118 on care pathway, CG2 135 not on care pathway) | Training and support | Predominantly indirect | Palliative care nurse practitioner, palliative care medical officer |

The overall % of dying residents transferred to hospital decreased but there was no statistical testing. The % of dying IG residents on the end-of-life pathway transferred to hospital was significantly smaller than the % of those not on the care pathway: p < .001 |

Weak |

|

Smith and Brown (2017 (UK) |

One group cohort (pre +post) | 3 nursing homes: number of residents NR | Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | Direct and indirect | Unclear (nursing home facilitator) | The number of deaths in hospital was lower in the IG than the CG but there was no statistical testing | Weak |

- Grey shading indicates those studies for which reducing hospital admissions was not a specific aim.

- NR, Not reported; IG, intervention group; CG, control group.

- a From the EPHPP.

- b Additional staff input over and above the comparator.

- c The blinding and data collection sections of the quality appraisal tool were adapted to reflect the fact that while hospitalization is a tangible event, there were sometimes uncertainties about the robustness of the data collection methods. However, this may have resulted in some studies being given a lower global rating than would otherwise have been the case.

Twenty studies were randomized controlled trials, six controlled clinical trials, 16 cohort analytic studies (two- or three-group pre and post) and 30 cohort studies (one group pre and post). Other designs included eleven (two or three groups) observational cohorts and six descriptive studies in which reported outcomes commonly constituted professional judgements of avoided admissions. Participating facilities included nursing homes, residential homes, assisted living facilities and senior living communities (hereafter ‘care homes’). Sample sizes (alternatively reported as numbers of care homes, beds, residents and consultations) varied greatly; the number of care homes ranged from 1 to 405 and the number of residents from 14 to 61,636, although not all studies provided this information. Most included all older residents. However, some focused on particular subgroups, for example, residents with dementia.

3.3 Study quality

A total of 12 studies were rated strong in quality, 32 moderate and 48 weak. Of the latter, half had weak ratings on two EPHPP domains, 13 on three, 7 on four, and 4 on five. Following EPHPP guidance, 18 weak-rated studies had weak study designs. The three most common reasons for weak classifications were as follows: sample/selection bias (38/48, e.g. low probability participants represented the wider population); data collection methods (33/48, e.g. doubts about data reliability) and the potential for (uncontrolled for) confounders (24/48). Supplementary Appendix S3 provides further details.

3.4 Focus of the initiatives

Thirty-two initiatives focused on residents’ general physical health, 15 on acute illness or at risk of hospital admission, 20 end-of-life care and 6 post-hospital discharge. Ten sought to optimize residents’ medication; others focused on specific health concerns including falls and pressure ulcers.

3.5 Characteristics of the initiatives

Not all studies provided detail of participating practitioners. However, at least 46 initiatives were delivered by multidisciplinary teams (MDTs). Nurses (often advanced/specialist practitioners) participated in at least 61 initiatives and physicians at least 49. Other disciplines included pharmacists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, dieticians and emergency care practitioners. Most professional support was provided face to face. However, seven studies evaluated telemedicine services.

Table 4 shows the distribution of the initiatives according to the taxonomies. Employing Taxonomy 1, 55 initiatives provided assessment and management, 13 assessment only and 24 education or training. Using Taxonomy 2, 40 provided predominantly direct care, 26 predominantly indirect care and 26 both.

| Taxonomy 1 | Taxonomy 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Prevalence (n) | Model | Prevalence (n) |

| Assessment, no medical practitioner involvement | 5 | Predominantly direct | 40 |

| Assessment, medical practitioner involvement | 8 | Direct and indirect | 26 |

| Assessment and management, no medical practitioner involvement | 19 | Predominantly indirect | 26 |

| Assessment and management, medical practitioner involvement | 36 | ||

| Training and support | 24 | ||

3.6 Characteristics of comparator services

Outcomes of specialist initiatives were typically compared with ‘standard’ or ‘usual’ care. However, in a minority, the comparator constituted an earlier iteration of the intervention. In most studies ‘usual care’ was simply conceptualized as the absence of the additional support the specialist service provided.

3.7 Service effectiveness

3.7.1 Effect on hospital admissions/emergency department transfers

Seventy-five studies that specifically sought to reduce hospital admissions/ED transfers provided data on hospital resource use, of which 11 were rated strong and 24 moderate in quality (Table 2; Supplementary Appendix S2). Eleven studies were entered into a meta-analysis but given the substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 100%, Figure 2, Forest Plot A), the results were not meaningful. Excluding weak studies and studies only providing ED visit data did not markedly reduce the high level of heterogeneity (Forest Plots B and C).

The following subsections synthesize and describe the findings according to the foci of intervention and model of specialist support using vote counting based on direction of effect. Sensitivity analyses are reported only where they cast doubt on the robustness of the main analysis.

General health

Twenty-seven studies aiming to improve residents’ general health provided data on hospital admissions/ED transfers, of which 24 favoured the intervention: 89%, 95% CI 72% to 96%, p < .0001 (p < .001 corrected for multiple testing), indicating evidence of an effect. One was rated strong in quality, nine moderate and 14 weak. Most provided assessment and management, but two were assessment-only services (Bellantonio et al., 2008; Hex et al., 2015*) and two training and support initiatives (broad quality improvement programmes, Cool et al., 2018; Ouslander et al., 2011; Rolland et al., 2016).

Some of the strongest evidence came from New Zealand, where ED transfers fell 27% on the introduction of a multidisciplinary support service (Connolly et al., 2018). A similar initiative for residents with ‘big five’ diagnoses (cardiac failure, ischaemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke and pneumonia) also reported positive effects (Connolly et al., 2015, 2016), as did a nursing intervention with more emphasis on training (Boyd et al., 2014).

Three other moderately rated studies reporting beneficial outcomes involved both nurses and doctors. In Australia, specialist practice nurses provided assessment, support, education and training with input from a geriatrician (Street et al., 2015); in Hong Kong, community geriatric team nurses assessed all residents, and geriatricians subsequently assessed and reviewed those with complex needs, polypharmacy or frequent readmissions (Luk et al., 2002); in the USA, nurse practitioners and primary care physicians detected problems early and managed them aggressively (Kane et al., 2003, 2004). However, a Dutch initiative by trained nurse assistants with optional geriatrician/psychologist consultation reported increased admissions (Boorsma et al., 2011).

Four weak-rated multidisciplinary assessment and management initiatives involving doctors and nurses reported reduced admissions (Ackermann & Kemle, 1998; Hui & Woo, 2002; Hui et al., 2001; Lisk et al., 2012; Sankaran et al., 2010), as did several other weak-rated enhanced primary care initiatives (Aigner et al., 2004; Burl & Bonner, 1991; Bynum et al., 2011; Codde et al., 2010; Klaasen et al., 2009; Lacny et al., 2016; Pain et al., 2014). A similar UK intervention, however, reported increased admissions (Gordon et al., 2018*).

Two of three other nurse-staffed services (Arendts et al., 2018; El-Masri et al., 2015; Ono et al., 2015*) and a study of a UK nurse/pharmacist collaboration (Winstanley & Brennan, 2007) also reported reduced admissions.

Urgent care

Thirteen initiatives for acutely unwell residents provided data on ED transfers/hospital admissions, of which 11 reported beneficial outcomes, indicating evidence of effectiveness: 85%, 95% CI 58% to 0.96%, p = .01. However, this was no longer statistically significant after correction for multiple testing (p = .06). Four were rated strong in quality, two moderate and five weak. Sensitivity analysis treating studies reporting mixed outcomes as negative rather than positive also changed the results so the null hypothesis (no difference between groups) could not be rejected, with 10/13 initiatives favouring the intervention: 77%, 95% CI 50% to 92%, p = .09.

Two US telemedicine services reported reduced ED transfers/admissions—a nurse–doctor assessment service (Grabowski & O’Malley, 2014*) and a geriatric medicine provider assessment and management initiative (Shah et al., 2015). A UK assessment-based emergency practitioner service (Mason et al., 2012*) and Canadian paramedic assessment and management service (Jensen et al., 2016*) also reported fewer hospital referrals, albeit both were rated weak.

Of two Australian ‘Hospital in the Home’ assessment and management of admission-avoidance services, one nursing service failed to demonstrate a clear effect (Crilly et al., 2010). However, the second (strong-rated) medical and nursing initiative reported lower rates of hospital transfer/admissions (Fan et al., 2016), as did several similar services. These included two further strong-rated Australian geriatric outreach services (Chan et al., 2018; Hutchinson et al., 2015), and six moderate-rated US initiatives whereby embedded nurse practitioners provided direct patient care (Ingber et al., 2017; Rantz et al., 2017; Rantz, Popejoy, et al., 2017). A Canadian study in which registered nurses visited care homes on predefined schedules also reported reduced ED transfers (Bandurchin et al., 2011*), but was deemed weak in quality.

Two customized educational initiatives (Hullick et al., 2016; Tena-Nelson et al., 2012*) reported positive effects.

End-of-life care

Of 11 end-of-life care studies that provided data on hospital transfers/admissions, nine explicitly sought to reduce these (Chapman et al., 2018; Garden et al., 2016; Hockley et al., 2010; Kinley et al., 2018; Kuhn & Forrest, 2012; Kunte et al., 2017; Luk & Chan, 2017; O’Sullivan et al., 2016; Teo et al., 2014). Six studies favoured the intervention (Garden et al., 2016; Kinley et al., 2018; Kunte et al., 2017; Luk & Chan, 2017; O’Sullivan et al., 2016; Teo et al., 2014). However, all were rated weak and the null hypothesis could not be rejected: 66%, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.88, p = .25. Section 3.7.2 provides more information about these services’ effect on place of death.

Medication

Of ten studies aiming to improve prescribing, six sought to reduce hospitalization and provided data on ED transfer/admission numbers (García-Gollarte et al., 2014; Lapane, Hughes, Christian, et al., 2011; Lapane et al., 2011; McKee et al., 2016; Roberts et al., 2001; Zermansky et al., 2006). Of these, four favoured the intervention (one strong, two moderate and one weak). Three involved medication reviews by clinical pharmacists (Lapane, Hughes, Christian, et al., 2011; McKee et al., 2016; Zermansky et al., 2006) and the fourth a 10-hour training programme (García-Gollarte et al., 2014). However, synthesis suggested the null hypothesis could not be rejected: 66%, 95% CI 30% to 90%, p = .34.

Post-hospital discharge

All six studies evaluating post-hospital discharge services reported decreased admissions/re-admissions, suggesting a positive effect: 100%, 95% CI 61% to 100%, p = .015. However, this was no longer statistically significant after correction for multiple testing (p = .09). One was rated strong, three moderate and two weak. When studies reporting mixed findings were classed as negative rather than positive, the null hypothesis could also no longer be rejected, although 5/6 studies favoured the intervention: 83%, 95% CI 44% to 97%, p = .11.

Of three Danish studies, one evaluated a rehabilitation intervention post hip fracture provided by a geriatric orthopaedic team (Gregersen et al., 2011) and two investigated general health support services provided by nurse–physician geriatric teams (Pedersen et al., 2016, 2018). Each assessed care home residents on the first working day post-discharge, while the services available in the general health initiatives variously included telephone advice, blood tests, electrocardiograms, intravenous antibiotics, oxygen, subcutaneous fluids and blood transfusions (Pedersen et al., 2016, 2018). Two further initiatives also provided assessment and management (Harvey et al., 2014; Schubert et al., 2016), while in the sixth, a geriatrician/nurse practitioner assessment service, the initial visit was somewhat later than in the Danish studies, but support continued longer (Cordato et al., 2018).

Other specialist initiatives

Five training initiatives focused on preventing falls/hip fracture (Walker et al., 2016; Ward et al., 2010); falls, pressure ulcers and incontinence (Brownhill, 2013); pneumonia (Hutt et al., 2011) and the provision of intravenous fluids/antibiotics (Romøren et al., 2017) with a view to reducing hospitalization. Three favoured the intervention (Brownhill, 2013; Hutt et al., 2011; Romøren et al., 2017). However, synthesis suggested that the null hypothesis could not be rejected: 60%, 95% CI 23% to 88%, p = .5.

Taxonomies of specialist care home support

Taxonomy 1. Seven of nine assessment-only interventions (with/without medical practitioner involvement) (78%, 95% CI 45% to 94%, p = .09) favoured the intervention. Thus, the null hypotheses could not be rejected. There was, however, evidence that assessment and management interventions (with/without medical practitioner involvement) had an effect, with 36 of 43 studies favouring the intervention: 84%, 95% CI 70% to 92%, p < .00001 (p < .0001 when corrected for multiple testing). Syntheses of all non-training initiatives with medical practitioner involvement also showed evidence of effectiveness, with 32/36 studies favouring the intervention: 89%, 95% CI 75% to 96%, p < .00001 (p < .0001 when corrected for multiple testing). Conversely, synthesis of non-training interventions without medical involvement failed to reject the null hypothesis, 11 of 16 studies favouring the intervention: 69%, 95% CI 44% to 86%, p = .10. Synthesis of training only initiatives (with/without medical practitioner involvement) also showed evidence of effectiveness, with 11 of 14 favouring the intervention: 78%, 95% CI 52% to 92%, p = .029. However, this was no longer statistically significant after correction for multiple testing (p = .15).

Taxonomy 2. Twenty-eight of 30 interventions providing predominantly direct care favoured the intervention, showing evidence of an effect: 93%, 95% CI 79% to 98%, p < .00001 (p = .00003 when corrected for multiple testing). Predominantly indirect care also showed an effect in the main analyses, with 12/15 studies favouring the intervention: 80%, 95% CI 55% to 93%, p = .017 (p = .05 when corrected for multiple testing), but this was not sustained in sensitivity analyses: 67%, 95% CI 42% to 85%, p = .15. Synthesis of interventions providing direct and indirect care failed to reject the null hypothesis, 14 of 21 studies favouring the intervention: 67%, 95% CI 45% to 83%, p = .09.

3.7.2 Effect on place of death

Fifteen studies provided data on residents’ place of death, of which 14 aimed to reduce hospital admissions (Table 3; Supplementary Appendix S3). All evaluated end-of-life care initiatives, with five considered moderate and nine weak in quality. Nine provided training and support in palliative care and/or advance care planning (Baron et al., 2015; Brännström et al., 2016; Covington, 2013; Cox et al., 2017; Hockley & Kinley, 2016; Kinley et al., 2014, 2018; O’Sullivan et al., 2016; Reymond et al., 2011), of which four drew on the Gold Standards Framework quality improvement training programmes (Baron et al., 2015; Covington, 2013; Hockley & Kinley, 2016; Kinley et al., 2014), and others the (subsequently phased out) Liverpool Care Pathway (Brännström et al., 2016; Kinley et al., 2014; Reymond et al., 2011). The remainder involved training and assessment and/or management by external care practitioners (generally nurses) (Bynum et al., 2011; Chapman et al., 2018; Finucane et al., 2013; Hockley et al., 2010; Smith & Brown, 2017). Overall, 13/14 studies favoured the intervention, demonstrating evidence of effectiveness: 93%, 95% CI 68% to 99%, p < .001.

3.8 Healthcare expenditure

Thirty-four studies provided service cost information (Supplementary Appendix S4). However, only two undertook full cost-effectiveness analyses (Lacny et al., 2016; Sackley et al., 2016). Neither had a significant effect on hospital admissions and only one explicitly aimed to reduce admissions (Lacny et al., 2016).

Of 19 moderate-/strong-rated studies with significant effects on transfers/admissions, five provided cost data. Each reported savings (Boyd et al., 2014; Chan et al., 2018; Cordato et al., 2018; Ingber et al., 2017; Kane et al., 2003, 2004), but only three undertook formal cost evaluations. The total costs (inpatient, ED presentations and physician visit costs) of an Australian post-hospital discharge service (Cordato et al., 2018) were $91,854 (mean $4175) compared with $175,517 (mean $8358) for the control group, while an Australian Acute Geriatric Outreach Service reported average savings of $2353 per person from reduced admission and ambulance transfer frequency (Chan et al., 2018). In seven US urgent care initiatives, average per resident Medicare expenditures reduced by $60–$2248 for all-cause hospitalizations and $98–$577 for potentially avoidable hospitalizations (Ingber et al., 2017).

4 DISCUSSION