FEASIBILITY OF COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY IN AWAKE DOGS WITH TRAUMATIC PELVIC FRACTURE

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (KRF-2010-013-E00029).

Abstract

In veterinary medicine, general anesthesia or sedation is generally required to immobilize patients during computed tomography (CT) scanning. This may not be suitable in all patients because of risks of anesthesia. We evaluated the feasibility of pelvic CT examination in 14 awake animals with pelvic trauma. Physical restraint was applied by wrapping the patient in a towel and then taping to the CT table or by directly taping the patient to the CT table. The effect of patient positioning, cooperation on the CT table, preparation time for scanning, scanning time, frequency of repeat scans, image quality, and complications related to physical restraint were evaluated. Fractures were recorded and compared between radiography and CT. Ten of 14 dogs were scanned in lateral recumbency and four in sternal recumbency. All patients were cooperative with the exception of one that moved slightly during the scan. Both physical restraint methods were adequate for CT scanning. Patient preparation took less than 5 min while the scan time was typically less than 1 min. No repeat scans were required in any patient. The transverse CT image quality was good (10/14) or fair (4/14) for interpretation. When comparing the CT images to radiographs, more pelvic fractures were identified with CT than with radiography and a few patients were overdiagnosed based on radiographs. No complications or additional injuries associated with physical restraint were noticed.

Introduction

Computed tomography (CT) is useful for evaluation of complicated fractures since cross-sectional and reformatted three-dimensional (3D) images can provide detailed anatomic information and aid in formulating treatment plans.1-3 For example, CT is more sensitive than radiography in dogs to detect complex fractures of the acetabulum and sacrum.3 Thus, CT is recommended when there are ambiguous radiographic findings regarding a pelvic facture.3

In general, sedation or anesthesia is recommended in animals undergoing CT to reduce motion artifact.4 However, this may not be possible in traumatized animals with other medical abnormalities. Therefore, we sought to assess the feasibility of performing CT studies in dogs with pelvic fracture using only physical restraint. The hypothesis was that CT of awake patients with pelvic trauma can be performed easily and that image quality would be acceptable.

Materials and Methods

This was a prospective study performed from September 2010 to July 2011. Dogs were included if: (a) they had a radiographically confirmed pelvic fracture, (b) there was concern for sedation or anesthesia due to coexisting thoracic trauma or cost, (c) they were scanned by CT without anesthesia or deep sedation, and (d) there was consent from the clinician and owner. Fourteen patients with a pelvic fracture were identified. Eight were small (Shit Tzu, Spitz, Miniature Poodle, Maltese, Mix and Pug), five were medium size (Cocker Spaniel, Beagle, Jindo, and Pungsan) and one was large (Golden Retriever). The average age and body weight were 2.8 years (range 5 months to 9 years) and 7 kg (range 1.6–17 kg), respectively. All patients had pelvic pain but were generally stable and comfortable enough for CT imaging. Four of 14 patients had mild respiratory distress due to coexisting injuries such as presumptive pulmonary contusion in three cases, and a diaphragmatic hernia in one, but they were stable otherwise. There was moderate azotemia in four dogs. For pain management, tramadol or butorphanol was administered before CT imaging.

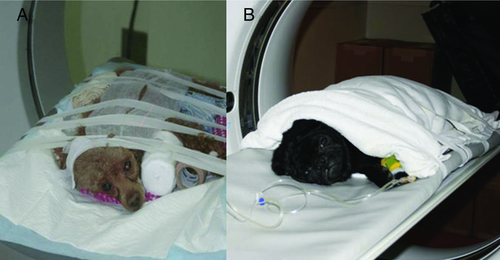

The restraint methods in this study were a combination of towel wrapping and taping, and taping alone. The towel wrapping method was modified from a method for rabbit restraing.5 The torso and limbs were wrapped leaving only a portion of the head exposed. The wrapped patient was fastened to the CT table using tape for safety and security. In cooperative patients, it was not necessary to secure the forelimbs. The patient was positioned feet first in either lateral or dorsal recumbency, whichever was most comfortable for the patient. Once the animal was secured on the CT table, they were monitored for airway patency and breathing pattern.

CT studies were performed with a helical scanner1, 2. The CT scanning parameters such as kVp, mA, pitch, and field of view varied depending on the size of the patient. The CT and radiographic image sets were anonymized and randomized. All imaging studies were assessed using standard medical image viewing software3 except for a few analog radiographs. To better evaluate and characterize fractures, 3D CT images produced by commercial software4 were reviewed. The images were evaluated independently by three board-certified radiologists (HGH, JJR, JFN) for transverse CT image quality using a scoring system (Table 1). The type of fracture, bone or joint involvement on both radiography and CT were evaluated by reviewer consensus.

| Score | Description | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Good | Absent or nearly imperceivable motion artifact, good for interpretation |

| 2 | Fair | Noticeable motion artifact, adequate for interpretation |

| 3 | Nonacceptable | Severe motion artifact, inadequate for interpretation |

Results

Two patients were restrained with taping alone while twelve patients were restrained with the combination of towel wrapping and taping method (Figs. 1 and 2). Both physical restraint methods worked well for immobilization and stabilization. The preparation time was less than 5 min (13/14 were less than 3 min). The average scan time for the pelvic region was approximately 1 min in all patients. The mean time between injury and CT scanning was 19.1 h (range 2–36 h). The time from presentation to CT scanning was less than 60 min except in two dogs, where the time was between 2 and 3 h. No repeat scan was required for any patient. No dog exhibited any visible sign of stress during the CT study. All patients were cooperative and calm except one that struggled to get out of the draped towel before and during CT scanning.

No complications were observed before, during, or after the CT study. No change in vital signs, including body temperature, heart rate, and respiratory rate were found.

CT image quality was good in 10 patients and fair in the remaining 4. Radiographs of two patients were not available for evaluation as they were misplaced by the referring veterinarian.

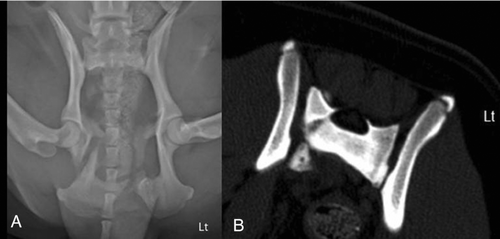

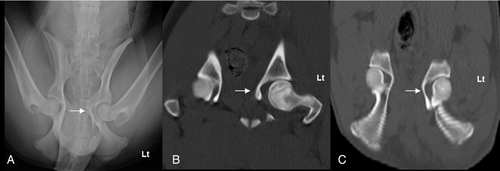

Comparison of CT images with conventional radiographs was performed in 12 of the 14 patients. Sacroiliac joint subluxation which was not identified radiographically was observed on CT images in 3 of 12 patients. Bilateral sacroiliac subluxation that was suspected radiographically was confirmed as a unilateral subluxation on CT images in two patients. Sacral fractures which were not detected radiographically were observed in 5 of the 12 patients and sacral fractures suspected radiographically were ruled out based on CT images in two patients. In three patients, a false positive radiographic diagnosis of an acetabular fracture was ruled out based on CT images (Fig. 3). One patient with a radiographic diagnosis of a unilateral acetabular fracture was confirmed as a bilateral fracture on CT. In two patients, iliac fractures were not seen on radiographs, while a fracture detected on radiographs was confirmed to be normal on the CT study. Pubic fractures were not detected on radiographs but were detected on CT images in two patients. There was one false positive radiographic diagnosis of a pubic fracture. As for ischial fractures, they were not detected on radiographs but were present on CT images in two patients. A false positive radiographic diagnosis of an ischial fracture was seen in one patient.

Discussion

Based on our results, CT without anesthesia or sedation is feasible in dogs with traumatic pelvic fracture and image quality is good. Anesthetized patients must be monitored closely during imaging to avoid complications such as regurgitation or respiratory compromise. Therefore, in human pediatric radiology, sedation during CT is avoided with the aid of analgesics special instrumentation, such as a video viewing system/video goggle, while the patient is in the CT scanner.6

In this study, all initial survey pelvic radiographs were performed without anesthesia or sedation. Repeat pelvic radiography may be performed before surgery with the patient under anesthesia to further characterize the fracture for correct surgical planning. Additional views may be required for better assessment of the lumbosacral spine.7, 8 During pelvic radiography, care should be taken to prevent further damage to important structures, such as the sciatic nerve, by careful patient handling.9 No further radiographs were required in our study because the CT study provided adequate anatomic information for surgical planning. Pelvic radiographs were not evaluated in two dogs in this study because they were misplaced.

In some studies, a transparent positioning device has been used successfully for restraint during CT imaging.10, 11 In our study, towel wrapping with tape, or taping alone, was adequate. Initially, taping alone was used. Later, towel wrapping combined with taping was used to prevent adhesion of the tape to the hair coat and for better restraint.

The position of the patient varied to aid in patient comfort. Most patients were cooperative with the exception of one that was slightly resistant to restraint. However, the image quality of the CT images of that patient was still acceptable (score 1.7). Even though neither the patient nor the pelvis were symmetric, the assessment of pelvic fractures was still possible by scrolling backward and forward through the imaging series.

Even though patients were not sedated or anesthetized, airway patency and breathing were monitored carefully. No special attention was required for airway patency as all dogs were breathing voluntarily. Restraint methods did not interfere with the airway. Breathing was not compromised regardless of the restraint method. Minor respiratory distress was seen in a patient that was wrapped too tightly, however slight adjustment of the wrap alleviated the distress. Throughout the CT studies, the stress related to physical restraint was well tolerated and negligible.

Patients struggling and falling from the CT table while scanning was of concern but this did not occur. The risk of falling during CT in these patients is low as they are unwilling to move due to pain. However, the patients were always monitored closely throughout the CT study. The temperature, pulse, and respiration were similar between pre and post CT study. No oxygen supplementation was needed.

The time interval between injury and presentation was long, approximately 20 h, mostly due to the referral procedure, indicating that the patients we examined may have been relatively stable after the injury in comparison to more seriously injured patients. Similarly, the short time between presentation and CT imaging was most likely due to the stable condition of the patients; therefore diagnostic decisions were made in shorter time. The gantry speed of the CT machines used in this study was approximately 0.7 second per rotation resulting in 90 axial images with 3mm slice thickness which covers 30 cm in length in 60 s. Faster CT scanners would be more useful for obtaining images within a few breaths. It would not be a problem for a single slice helical CT unit to acquire good quality images of the entire pelvic region in small sized dogs within a few minutes, as in this study. Generally, the preparation time from anesthetizing or sedating a patient to positioning the patient on the CT table is approximately 10 min. Additional monitoring of body temperature and cardiac and respiratory function require more personnel both during and after imaging. In this study, the time from patient immobilization to positioning on the CT table was less than 5 min in all dogs and in 13 of 14 the time was less than 3 min.

The transverse CT image quality was generally good. Ten of 14 had good images with no interference for evaluation of pelvic fracture. Slight motion artifacts related to breathing, and positional asymmetry were unavoidable but they did not affect fracture assessment. In three of 14 dogs, the CT image quality with noticeable motion artifact was fair, but there were no interference with evaluation of the pelvic injury. The lowest quality transverse image resulted in challenges for evaluation of the pelvic trauma. This may have been related to the field of view being too large and/or sudden motion of the couch and noise causing anxiety with perceptible motion artifact. Therefore, rescanning may be needed occasionally but none was performed in this study as image quality was always judged to be acceptable.

When comparing CT images to radiographs, more pelvic fractures were identified with CT than with radiography and a few patients had fractures diagnosed radiographically that were not present. These results are similar to prior work where 57% of sacral fractures were missed based on radiographic assessment.12 Therefore, CT seems to be more accurate than radiography for evaluation of pelvic fractures. Clinically, sacral fractures and sacroiliac luxations are the most frequent injuries related with neurologic deficits in people.13, 14 In dogs, sacral fracture as well as sacroiliac luxations with cranial displacement of the ilium or ilial fractures with craniomedial displacement could be a major cause of neurologic dysfunction.15, 16 Therefore precise characterization of pelvic fractures with CT images combined with neurologic examination will be beneficial for treatment planning.

We did have some difficulty recruiting patients as most clinicians and owners were reluctant to approve CT imaging without anesthesia or sedation. This is most likely due to a traditional mindset but we hope that our results will alter this perception.4 Also, we did not include patients with greater anesthetic risk due to severe thoracic trauma except for one with a diaphragmatic hernia. This may be due to lack of such patients during the study period or they may have been excluded by clinicians deeming them unsuitable for CT scanning without chemical restraint.

In conclusion, physical restraint without sedation or anesthesia was feasible for CT imaging in dogs with traumatic pelvic fractures. The image quality was mainly adequate for interpretation and symmetric positioning was not critical for accurate evaluation of pelvic fractures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (KRF-2010-013-E00029).