IMAGING DIAGNOSIS: CT FINDINGS IN A DOG WITH INTRACRANIAL HEMORRHAGE SECONDARY TO ANGIOSTRONGYLOSIS

Abstract

A seven-month-old Cocker Spaniel had a cough, acute lethargy, decreased responsiveness, and episodes of hyperexcitability. There were bilateral generalized increased lung sounds, bilateral episcleral hemorrhage, and systemic hypertension. Prolonged buccal mucosal bleeding time and elevated D-dimer concentrations were detected. Radiographically, there was a generalized moderate unstructured interstitial pattern. In thoracic CT images, there was a diffuse moderate hyperattenuating appearance of the bronchial walls and interstitium and diffuse areas of moderate bronchiectasis. The brain CT images were characterized by marked hyperattenuating well-defined masses. In addition, there were smaller hyperattenuating and hypoattenuating masses scattered throughout the cerebral and cerebellar parenchyma. A zinc sulphate flotation test confirmed large numbers of Angiostrongylus vasorum L1 larvae. Despite therapy the dog continued to deteriorate and underwent euthanasia. Postmortem examination confirmed the presence of multiple intracranial and extracranial hemorrhages. Angiostrongylosis should be considered as one of the differential diagnoses in dogs presenting with neurologic signs consistent with acute intracranial haemorrhage.

Signalment, History, and Clinical Findings

A seven-month-old Cocker Spaniel had a cough of 2-week's duration and acute lethargy. There were bradycardia (64 bpm), bilateral generalized increased lung sounds, bilateral episcleral hemorrhage, and systemic hypertension (180–200 mmHg). The concurrent bradycardia and systemic hypertension was suggestive of elevated intracranial pressure (Cushing response). Prolonged buccal mucosal bleeding time (>5 min), with elevated D-dimer concentrations (1.29 mg/l [<0.075]) were detected. Other tests of primary (platelet number, von Willebrand factor antigen assay) and secondary (prothrombin time [PT] and activated partial thromboplastin time [aPTT]) coagulation were within reference limits. Due to the concurrent respiratory and hemorrhagic signs, a fecal sample was submitted for the investigation of angiostrongylosis that is endemic in Ireland.1

Diagnostic Imaging

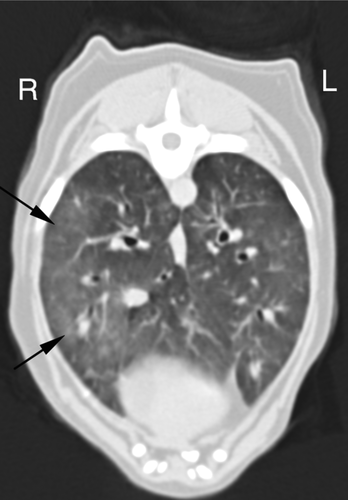

Thoracic radiographs were characterized by a moderate unstructured interstitial pattern. CT images of the thorax were acquired in a conscious state. There was a diffuse moderate hyperattenuating appearance to the airways and interstitium, and diffuse areas of moderate bronchiectasis. Large areas of the lung had a mild, diffuse, increased hyperattenuation, Hounsfield unit (HU) between −350 and −470 (Fig. 1). These changes were consistent with parasitic pneumonia and acute pulmonary hemorrhage.

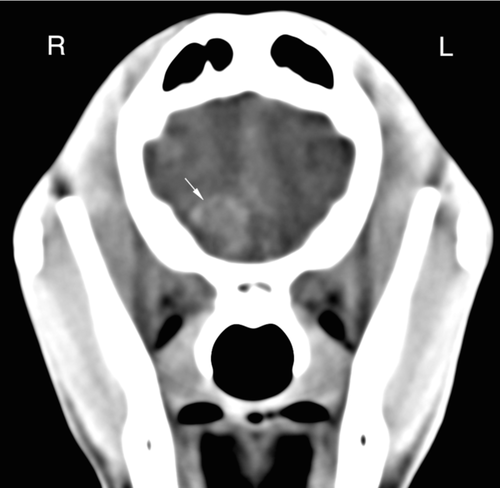

Pre- and postcontrast CT images of the brain were acquired. Precontrast images of the brain were characterized by a hyperattenuating mass (38 HU) in the rostral portion of the forebrain at the level of right olfactory bulb (Fig. 2). Another well-defined hyperattenuating (39 HU) mass was present in the left caudal portion of the forebrain (Fig. 3). A hypoattenuating rim encircled both masses; this was interpreted as perilesional edema. In addition, there were smaller hyperattenuating and hypoattenuating nodules scattered throughout the cerebral and cerebellar parenchyma. There was no contrast enhancement of the hypoattenuating nodules or the hyperattenuating mass in the brain. These changes were consistent with widespread chronic and acute parenchymal hemorrhage, respectively.

The radiographic and CT thoracic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of chronic lung infection of Angiostrongylus vasorum. The CT brain findings were consistent with acute intracranial hemorrhages.

Diagnosis and Outcome

A zinc sulphate fecal flotation test confirmed large numbers of A. vasorum L1 larvae. Despite therapy the dog continued to deteriorate and underwent euthanasia. Grossly, there was marked bilateral diffuse dark red pulmonary congestion with unclotted blood in the larynx and trachea. Tracheobronchial, mediastinal, and cranial mesenteric lymph nodes were enlarged. Multifocal, randomly distributed petechial hemorrhages were noted on the cerebral surface and a 2 cm × 1 cm hematoma was observed over the right olfactory bulb, extending into the brain parenchyma. A 0.5 cm × 1 cm hematoma was present in the left cerebral cortex. Cerebellar herniation into the foramen magnum was evident with a small amount of hemorrhage on the dorsal cerebellar surface.

Histopathologically, lungs were characterized by multiple granulomatous foci centered on parasite eggs and larvae of A. vasorum. There was widespread severe intraalveolar hemorrhage with associated scattered hemosiderophages. Adult larvae were present in blood vessel lumens. Multifocal randomly distributed hemorrhage was present in the cerebral, midbrain, and brainstem gray and white matter with hemosiderophages noted in these areas. Focally extensive hemorrhage and scatterings of neutrophils and macrophages were present in the overlying meninges. No parasites were evident in sections of brain tissue.

The final diagnosis was granulomatous pneumonia with intralesional angiostrongylus larvae with associated intracranial hemorrhage, diffuse brain swelling, and secondary mild cerebellar herniation.

Discussion

Canine angiostrongylosis is caused by A. vasorum, a metastrongylid nematode affecting domestic dogs and other canidae. This parasite has an indirect lifecycle requiring gastropods (snails or slugs) as an intermediate host.2 The mature helminth parasites are found in the right side of the heart and the pulmonary artery.3

The clinical signs associated with angiostrongylosis occur because of the inflammatory response to eggs and migrating larvae within pulmonary tissue, and hemorrhagic diatheses occurring secondary to chronic disseminated intravascular coagulation.4-7 This results in a broad spectrum of clinical signs including respiratory disease, local or diffuse hemorrhage, collapse, lethargy, exercise intolerance, vomiting, diarrhea, and neurologic signs such as conscious proprioceptive deficits, intention tremor, and blindness.8

Coagulopathies have also been reported widely in association with both naturally occurring and experimental A. vasorum infections.1, 4, 5, 8 The mechanism for this is poorly understood, but it is thought that antigenic factors secreted by the parasites may lead to excessive intravascular coagulation and a consumptive coagulopathy.4-7

Coagulopathies associated with angiostrogylosis have been reported to occur secondary to chronic disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), based on high D-dimer concentration, thrombocytopenia, prolonged clotting time, and decreased fibrinogen levels.6 In the current patient, only D-dimer concentrations were elevated. However, these tests lack sensitivity and it is possible that DIC was present despite the majority of test results being within normal limits. Thrombocytopenia has been reported in association with A. vasorum infection in a number of canine patients.1, 5-8

In 16 dogs with angiostrongylosis, the most frequent radiographic signs were an alveolar infiltrate in 13 (81%) and bronchial thickening in 11 (69%).9 In a radiographic and pathologic study of dogs infected experimentally with A. vasorum, the dogs developed a diffuse bronchial and interstitial pattern with a variable alveolar component affecting mainly the peripheral parts of the lungs.10 The alveolar pattern was most marked by 7–9 weeks after the infection10, 11 then decreased, leaving a bronchial and/or interstitial pattern.10 The changes seen in the thoracic radiographs in this dog are compatible with chronic stage infection.

The predominant pulmonary CT abnormality in dogs with low-grade experimental infection was multicentric ground-glass opacification, nodules of various sizes, and consolidation. Changes in the high-grade infection group were multiple large nodules merging to areas of consolidation and containing air bronchograms. On the CT studies, there was evidence of bronchial thickening and very mild peripheral bronchiectasis. Regional lymph nodes were enlarged.12

Automated volume histogram analysis of pulmonary CT images allowed differentiation of normal from abnormal lung in foxes infected with A. vasorum. This form of analysis is achieved readily and provides quantitative data that can be used to assess disease progression and response to treatment.13

Acute (days 1–3) hemorrhage is characterized in CT images by sharply circumscribed, homogeneous areas of hyperattenuation.14 The CT brain findings of our patient resemble those of acute stage of intracerebral hemorrhage.14

In humans, noncontrast CT of the brain is the standard imaging modality in the initial evaluation of patients with acute stroke symptoms. The primary advantage of CT in the hyperacute phase (0–6 h) is its ability to rule out hemorrhage. While conventional T1 and T2 weighted MRI pulse sequences are sensitive for the detection of subacute and chronic hemorrhage, they are less sensitive to parenchymal hemorrhage during the initial 6 h. Hyperacute parenchymal blood can be detected accurately using gradient echo pulse sequences that are sensitive to static magnetic field inhomogeneity.15.

The central nervous system signs in this dog were secondary to hemorrhagic diathesis induced by angiostrongylosis. The exact cause of this coagulopathy is poorly characterized, but can occur despite normal reference interval PT, APTT, and platelet counts.

At postmortem examination, cerebellar herniation was observed that was not discernable in the 3D CT reconstructions. This may have been due to the relatively large (3 mm) CT slice thickness, inadequate contrast resolution, or the fact that the postmortem examination was carried out 24 h after the CT scan.