IMAGING DIAGNOSIS—INTRA-ABDOMINAL NECROTIC LIPOMA

Signalment

Eleven-year-old, spayed female miniature Schnauzer dog.

History and Physical Findings

An 11-year-old spayed female miniature schnauzer had lethargy, inappetance, vomiting, urinary incontinence, and pollakiuria. The dog had a history of hyperadrenocorticism and was treated for diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and hepatitis. The dog was depressed and dehydrated with hepatomegaly and a midabdominal mass. There was hyperglycemia (149 mg/dl [reference range 71–120 mg/dl]), hypercholesterolemia (695 mg/dl [reference 119–341 mg/dl]), and mild to moderate increases in hepatic enzymes. Urinalysis was unremarkable other than the expected glucosuria.

Imaging

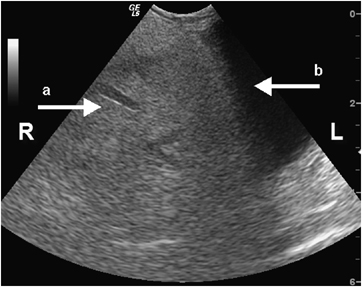

Abdominal sonography was performed* using a 7.5–10 MHz curved array transducer. The liver was homogeneously hyperechoic, consistent with diabetes and hyperadrenocorticism. Both kidneys were diffusely hyperechoic with decreased corticomedullary definition, mild pyelectasia, and focal mineralization. A mass, approximately 5 × 5.6 cm in diameter, was visible in the caudal abdomen. It was hyperechoic to the spleen and renal cortex. Based on Doppler ultrasonography, the mass was poorly vascularized with most of the blood flow at the periphery. The mass was adjacent to the spleen and cranial to the urinary bladder, causing compression of the bladder. Streak-like areas of hypoechoic tissue within the mass gave it a marbled appearance (Fig. 1). The overall echogenicity of the mass was similar to that of omental fat.

Transverse ultrasonographic image of a large hyperechoic mass of adipose tissue within the caudal abdomen compressing the urinary bladder. Note the hypoechoic streaks of necrosis and inflammation within the fatty mass (a) and the bladder mucosa (b).

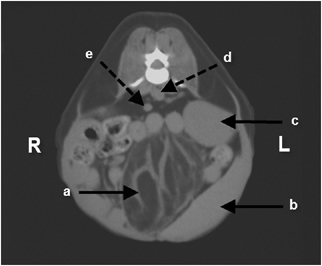

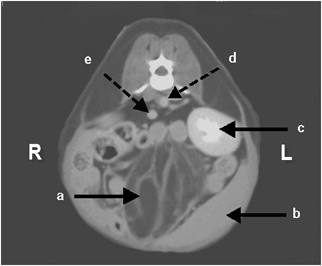

To better characterize the mass for surgical planning, contiguous transverse 5-mm helical computed tomography (CT) images† were obtained through the abdomen. A well-circumscribed, approximately 5 cm × 5.6 cm, mass with attenuation typical of fat was located in the mid to caudal abdomen. The mass did not appear to arise from either spleen or urinary bladder (Fig. 2). Hyperattenuating streaks were also present in the mass. There was no contrast enhancement of the mass after intravenous administration of 15 ml of iohexol‡ (Fig. 3). No other abnormalities were seen. The main considerations were lipoma and liposarcoma.

Transverse computed tomography image of a well-circumscribed mass of adipose tissue adjacent to the spleen and urinary bladder. Note the streaks of necrotic, inflamed fat interposed with the fibrous septae within the mass (a). Also note the close association between the mass and the spleen (b), the left kidney (c), the aorta (d), and the caudal vena cava (e).

Same transverse computed tomography image after intravenous administration of iodinated contrast medium. There was minimal contrast enhancement of the mass. Again, note the streaks of necrotic, inflamed fat interposed with the fibrous septae within the mass (a). Also note the close association between the mass and the spleen (b), the left kidney (c), the aorta (d), and the caudal vena cava (e).

Outcome

Based on a needle aspirate, the mass consisted of many clear nonstaining lipid vacuoles and several noncohesive aggregates of atypical spindle cells with moderate anisocytosis, multiple irregular nucleoli, and rare atypical mitotic figures. There was also evidence of fat necrosis. It was thought that this mass was most likely an intra-abdominal liposarcoma.

At surgery, a large, well-circumscribed mass of adipose tissue was found tightly adhered to the cranial aspect of the urinary bladder. The mass was removed and submitted for histopathologic examination; a small section of bladder had to be resected. Histologically, the mass was characterized as a necrotic lipoma with focal fibrosis. The areas of inflamed, necrotic fat interposed with fibrous septae were likely the source of the streaking seen in the sonographic and CT images. The dog made a complete recovery.

Discussion

Lipomas are benign fatty tumors and are the most common mesenchymal tumors in dogs. Breeds with a predilection for lipomas include Labrador retrievers, Doberman pinschers, and miniature Schnauzers. Most lipomas are subcutaneous, although intrathoracic, intra-abdominal, and intermuscular lipomas occur.1–6 Intra-abdominal lipomas are rare and become large before clinical signs of a space occupying mass or evidence of necrosis is seen. The pollakiuria in this patient was thought to be due to bladder compression with the mass and has not been reported as a primary presenting complaint in a dog with an intra-abdominal lipoma. Often, torsion of the mass on its vascular pedicle accounts for the necrosis, which is what likely happened in this dog. Intestinal strangulation has been caused by intra-abdominal lipomas in a dog.3 Intra-abdominal lipomas of the mesentary and greater omentum occur in human males and females of varying ages.1,7,8 The prognosis with intra-abdominal lipomas is excellent when they are removed in a timely manner.

The two prime considerations in this dog were lipoma and liposarcoma. In contrast to lipomas, liposarcomas are uncommon neoplasms that consist of malignant lipoblasts and mesenchymal tissue.9,10 They are locally invasive, and metastasis to liver, lung, and bone have been reported.11 In dogs, a forelimb liposarcoma occurred after a glass foreign body and another caused extradural spinal cord compression.12,13 Liposarcomas are not thought to arise from malignant transformation of existing lipomas.11

Liposarcomas and lipomas can be difficult to differentiate in animals and humans and histologic assessment is required for definitive diagnosis. This is especially true if there is concurrent inflammation or necrosis, as in this report.1,8,14 Importantly, there are differences in the imaging characteristics of lipomas vs. liposarcomas. Sonographically, lipomas are well-demarcated hypoechoic masses when compared with surrounding mesenteric fat. They are usually relatively avascular and do not invade surrounding structures.1,7 Liposarcomas may have a similar echogenicity but can be more vascular and invade surrounding structures.8 In this dog, abdominal ultrasonography helped characterize the vascularity of the mass, the bladder mucosa, and the demarcation between the hypoechoic areas of necrotic fat and the more hyperechoic fibrous septae. This pattern of echogenic demarcation on ultrasound has been reported in fatty masses with fibrous septae in humans.7 In this dog, the large size of the mass was a clear limitation in gaining information about the origin of the mass using ultrasonography alone. Identification of fat within a lesion is better achieved with CT than ultrasound.14 Identification of fat on CT imaging is based on X-ray attenuation. Fat appears dark, having Hounsfield unit values typically <−20.14 On CT imaging, lipomas have relatively homogenous attenuation typical of fat, whereas liposarcomas are irregular with thickened capsules and heterogeneous regions of attenuation.8,14 Well-differentiated liposarcomas can resemble lipomas with attenuation equal to that of fat. However, with liposarcomas, the fibrous septae are often thicker, more irregular, or more nodular than in lipomas.14

In this patient, the mass appeared fatty in CT images with hyperattenuating fibrous bands. Furthermore, with CT it was obvious that the mass did not arise from the bladder or spleen, although its origin was not definitively identified.