IMAGING FEATURES OF ORBITAL MYXOSARCOMA IN DOGS

This paper was presented at the International Veterinary Radiology Association Meeting 2006, Vancouver.

Abstract

Myxomas and myxosarcomas are infiltrative connective tissue tumors of fibroblastic origin that can be distinguished by the presence of abundant mucinous stroma. This paper describes the clinical and imaging features of orbital myxosarcoma in five dogs and suggests a predilection for the orbit. The main clinical signs were slowly progressive exophthalmos with soft swelling of the pterygopalatine fossa, and in two dogs, of the periorbital area. No pain was associated with the eye or orbit but one dog had pain on opening the mouth. The dogs were imaged using combinations of ultrasonography, radiography, and magnetic resonance imaging. In four dogs, extensive fluid-filled cavities in the orbit and fascial planes were seen and in the fifth dog, the tumor appeared more solid with small, peripheral cystic areas. In all dogs, the lesion extended along fascial planes to involve the temporomandibular joint, with osteolysis demonstrable in two dogs. Fluid aspirated from the cystic areas was viscous and sticky, mimicking that from a salivary mucocoele. Myxomas and myxosarcomas are known to be infiltrative and not readily amenable to surgical removal but their clinical course seems to be slow, with a reasonable survival time with palliative treatment. In humans, a juxta-articular form is recognized in which a prominent feature is the presence of dilated, cyst-like spaces filled with mucinous material. It is postulated that orbital myxosarcoma in dogs may be similar to the juxta-articular form in man, and may arise from the temporomandibular joint.

Introduction

Myxosarcomas and their benign counterpart myxomas are tumors of primitive fibroblastic origin that are characterized by an abundant, intercellular, mucinous ground substance. Grossly, they appear as soft, pale, poorly defined masses which exude a clear, tenacious fluid.1–4 They are rare in dogs, but have been reported to arise from a wide range of connective tissue sites in the body.1–4

In five dogs examined at the Animal Health Trust between 1993 and 2005 for investigation of exophthalmos, the final diagnosis was myxosarcoma involving the orbit. Radiography of the skull was performed in three dogs, ultrasonography of the orbit in four dogs and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the head in four dogs. Patient information, imaging findings, and outcome are described.

Patient Information

The patients comprised two Labrador Retrievers, one Golden Retriever, and two crossbreds weighing 19 and 30 kg. They were aged between 8 and 14 years; three were female (two neutered) and two were male (both neutered). In all dogs, third eyelid protrusion had progressed to exophthalmos over a period of time varying from 4 weeks to 1 year. The left eye was affected in four dogs and the right eye in the remaining dog. In one dog, the initial presenting sign had been development of painless, fluctuant soft tissue swellings ventral to the eye and in another dog, pain on opening the mouth had been noted several days before referral. In two dogs, the referring veterinarians had lanced and flushed an oral swelling ventral to the orbit, obtaining clear, viscous material in both dogs. Fluid analysis in one of these dogs was consistent with salivary mucocoele, but excisional biopsy of the surrounding tissue had been unremarkable.

All five dogs showed third eyelid protrusion and marked exophthalmos. In two dogs, the eye was also deviated dorsally or laterally. Retropulsion of the eye was relatively easy and painless in all dogs, although the clinical records did not record comparison of ease of retropulsion with the normal eye. The affected eye was visual in four dogs and blind in the fifth dog. Fluctuant soft tissue swelling was present in the periocular area in two dogs and ventral to the tongue in a third. In all dogs, swelling of the pterygopalatine fossa was evident on oral examination, varying from mild to marked. One dog had pain when the mouth was opened. The dogs were admitted for further investigations.

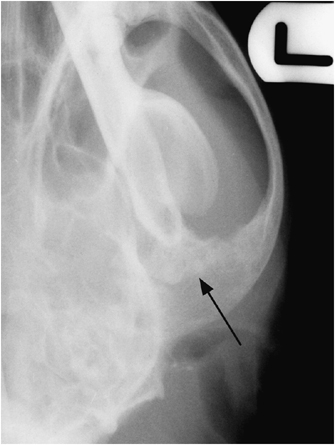

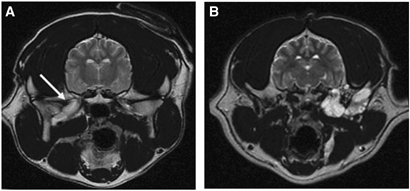

Ultrasonography

Four dogs underwent ocular ultrasonography and in each one, pockets of anechoic retrobulbar fluid were found (Fig. 1A and B). These varied in size from approximately 1–2.5 cm diameter and in two dogs were multiple. A hyperechoic margin to the fluid accumulation was reported in two dogs and in a third dog, the fluid appeared to surround an irregular, echogenic mass (Fig. 1C). The relatively anechoic appearance of the fluid suggested that these were not abscesses.

(A) Oblique dorsal plane ultrasonogram of the eye and orbit of a 12-year-old female entire crossbred dog. There is a discrete, anechoic structure in the orbit (white *) which was part of an extensive, multilocular/tubular cystic mass. (B) Oblique dorsal plane ultrasonogram of the eye and orbit of a 14-year-old male neutered crossbred dog. Note the cystic lesion abutting the back of the globe (white *). (C) Oblique dorsal plane ultrasonogram of the eye and orbit of an 11-year-old female neutered Labrador Retriever. Note the well-defined area of fluid accumulation (white *) surrounding an irregular, echogenic mass (black *).

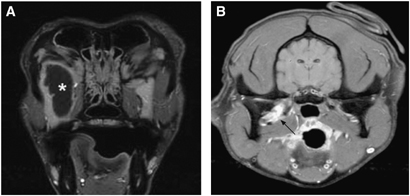

Radiography

Skull radiographs were obtained in three dogs. In the dog with pain on opening the mouth, permeative osteolysis of both the mandibular fossa of the temporal bone and the mandibular condyloid process was evident (Fig. 2). This was the dog in which fluid had appeared to surround an echogenic mass on orbital ultrasonography. A zygomatic sialogram was performed and was unremarkable except for compression of the caudal aspect of the salivary gland. Skull radiographs of a second dog had been made by the referring veterinarian and were said to be normal but were not submitted at the time of referral. However, upon retrospective examination of these radiographs, there was osteolysis of the mandible and temporomandibular joint. Thoracic radiography was performed in all five dogs and pulmonary metastasis was not detected.

Dorsoventral skull radiograph of an 11-year-old female neutered Labrador Retriever. There is irregular osteolysis of both the mandibular fossa and the mandibular condyloid process of the temporomandibular joint; same dog as in Fig. 1C.

MR Imaging

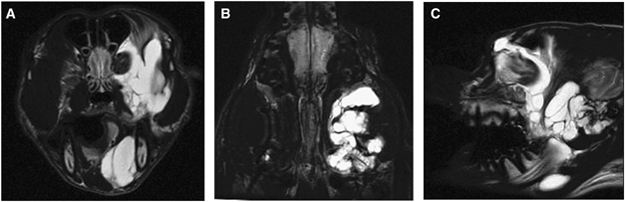

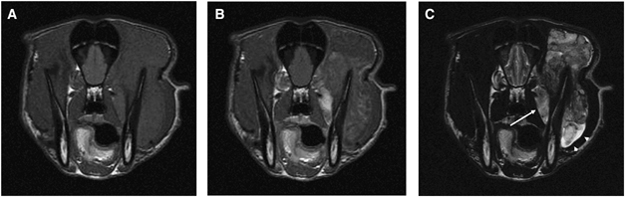

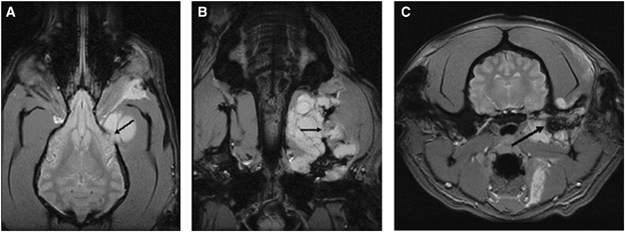

MR imaging was performed in four dogs. In all dogs, extensive disease was present within and beyond the confines of the orbit, the largest lesion measuring approximately 4 cm transversely, 13 cm dorsoventrally, and 12 cm rostrocaudally. This resulted in varying degrees of exophthalmos and pterygopalatine fossa swelling. In three dogs, the lesion consisted almost entirely of communicating, fluid-filled cavities with small areas of solid tissue caudally (Fig. 3A and B). In one dog, these cystic areas were highly complex giving a multiloculated appearance (Fig. 4A–C). In the fourth dog, the mass was predominantly solid and lobulated although small fluid pockets were identified caudoventrally, near the temporomandibular joint (Fig. 5A–C). This dog had undergone MR imaging elsewhere 10 months previously and there was remarkably little change, other than mild increase in size. All lesions were well defined and appeared to lie mainly within fascial planes rather than invading soft tissues, extending caudally between the zygomatic salivary gland and pterygoid muscles medially, and the mandibular coronoid process and temporal muscle laterally. All had intimate contact with the temporomandibular joint, either contacting it medially (two dogs) or encircling it (two dogs) (Fig. 6A and B). In one dog, the cystic orbital mass also extended rostrally in the intermandibular space (Fig. 4A).

Transverse, postcontrast, fat-suppressed, fast spin echo T1W (TR=550 ms and TE=15 ms) MR images at the level of the mid orbit (A) and the temporomandibular joint (B) in a 12-year-old female entire crossbred dog; same dog as in Fig. 1A. There is a large orbital lesion which is mainly cystic (white *) but which is surrounded by a rim of enhancing soft tissue. The lesion becomes more solid as it extends caudally towards the TMJ (arrow). Fluid within the lesion was slightly hyperintense to CSF.

Transverse (A), dorsal (B), and sagittal (C) fast spin echo T2W (TR=6000 ms and TE=84 ms) MR images of a 9-year-old female neutered Labrador Retriever. Note the extensive, multiloculated fluid accumulation in the orbit, extending rostrally in the intermandibular space and caudally to the temporomandibular joint.

Transverse fast spin echo precontrast T1W (TR=600 ms and TE=12 ms) (A), postcontrast T1W (B) and T2W (TR=4000 ms and TE=88 ms) (C) MR images of an 8-year-old male neutered Golden Retriever at the level of the caudal orbit. A large, heterogeneous mass is seen medial, dorsal and lateral to the coronoid process of the mandible and within a fascial plane near the orbital apex (arrow). The mass is subtly hyperintense to muscle on precontrast T1W, and has slight, uneven contrast enhancement indicating that it is poorly vascularized. On the T2W image, it is of mixed signal intensity and although mainly appearing solid, small fluid pockets are present caudoventrally (arrowheads).

(A) Transverse fast spin echo T2W (TR=4320 ms and TE=83 ms) MR image of a 12-year-old female entire crossbred dog at the level of the temporomandibular joint; same dog as in 1, 3. A hyperintense soft tissue mass lies medial to the temporomandibular joint (arrow) but there is no obvious osteolysis. (B) Transverse fast spin echo T2W (TR=6000 ms and TE=84 ms) MR image of a 9-year-old female neutered Labrador Retriever. There is an irregular, hyperintense mass encircling the temporomandibular joint; same dog as in Fig. 4A–C.

In the three dogs with predominantly cystic lesions, the fluid was isointense to CSF on T2W images and slightly hyperintense to CSF on T1W images (Fig. 3A). Administration of intravenous contrast medium (gadobenate dimeglumine* at 1 ml/10 kg) resulted in marked peripheral enhancement of the fluid-filled areas and also of the small areas of more solid tissue abutting the temporomandibular joints (Fig. 3A and B). The mainly solid soft tissue mass in the fourth dog was of heterogeneous, moderately hyperintense signal intensity on T2W images, was mildly hyperintense to muscle on T1W images and had only slight, patchy contrast enhancement with a wispy appearance suggesting poor vascularization (Fig. 5A–C).

In the dog with the large, complex, cystic lesion, marked osteolysis of the lateral aspect of the cranium, the coronoid process of the mandible and the temporomandibular joint was evident (Fig. 7A–C). In another dog, MR imaging allowed identification of subtle signal changes of the mandibular condyloid process in the temporomandibular joint, which were suggestive of minor osteolysis.

Dorsal (A and B) and transverse (C) T2* gradient echo (TR=600 ms, TE=15 ms and flip angle=20°) MR images of a 9-year-old female neutered Labrador Retriever. Note the osteolysis of the cranium (A—arrow), mandibular coronoid process (B—arrow) and temporomandibular joint (C—arrow) by an extensive soft tissue mass; same dog as in 4, 6.

Further Tests and Outcome

In the dog with marked temporomandibular joint osteolysis on radiographs (1, 2) excision arthroplasty of the temporomandibular joint was performed for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. MR imaging had not been performed on this dog. Following decalcification of the bone, a diagnosis of widely infiltrative myxosarcoma was made. The owners were informed that local tumor recurrence was likely and the dog was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Surgical biopsy was undertaken of the dog with the predominantly solid orbital mass (Fig. 5A–C) and the histologic diagnosis was myxosarcoma. Based on the size of the mass, neither surgery nor radiotherapy was considered viable options and it was recommended that the dog be treated with analgesic medications.

The remaining three dogs had lesions with a significant cystic component on MR images. Aspiration of the tumor via the pterygopalatine fossa yielded tenacious, clear to pink-tinged fluid in all dogs. The fluid was mucinous, proteinaceous and of low cellularity with scattered, well-differentiated epithelial cells. Biopsies were performed in two dogs and they contained small amounts of salivary tissue. The tentative histopathologic diagnosis was sialocoele in two dogs and mucus-producing salivary adenoma in the third although the presence of osteolysis on MR imaging in one of these dogs suggested a more aggressive process. All of these three dogs underwent subsequent palliative surgery. Marsupialization of the intermandibular portion of the lesion was performed in one dog (4, 6, 7) and a large volume of thick, mucinous fluid was released. Within a few days, the exophthalmos resolved and vision returned to the previously blind eye. Six months later, the dog had recurrent severe, recurrent exophthalmos. Repeat MR images were basically unchanged. An excisional biopsy obtained post-mortem confirmed a myxosarcoma.

Surgical biopsy and lesion drainage was also performed on another dog (1, 3, 6) and myxosarcoma was diagnosed histopathologically. The exophthalmos was slightly reduced by the surgery but subsequently recurred. The dog was managed for a further 10 months with symptomatic therapy and repeated fluid drainage via the pterygopalatine fossa.

A similar procedure was carried out on another dog (Fig. 1B) and myxosarcoma was confirmed from a biopsy. The procedure resulted in reduction of the exophthalmos but it did not completely resolve. In an MR imaging study repeated 5 months later, the lesion was essentially unchanged. The dog was still alive and clinically unchanged 9 months after the original investigation.

Discussion

Myxosarcomas are malignant tumors of primitive pleomorphic mesenchymal cells in which altered fibroblasts produce excessive mucin. They consist of loosely arranged stellate or spindle-shaped cells separated by an abundant mucinous matrix rich in mucopolysaccharides, which stain characteristically with Alcian blue.1–4 The term myxoid or myxomatous indicates a loose mesenchymal arrangement with a stroma containing mucinous material, and the presence of this stroma is the chief feature that distinguishes myxosarcoma and its benign counterpart myxoma from fibrosarcomas and fibromas, although the distinction may not always be clear.3,5 Histologic diagnosis is also difficult due to the paucity of cells that may be present in a sample and the fact that significant myxomatous change may also be seen in a number of other tumor types, including chondrosarcoma, liposarcoma, hemangiopericytoma, schwannoma, synovial sarcoma, smooth muscle tumors, embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, neurofibroma, and mucinous adenocarcinoma. Myxoid changes may also be seen in benign conditions of the skin and subcutis such as localized myxoedema or mucous cysts.1,2,5

The gross appearance of a myxosarcoma or myxoma is of a soft, pale, poorly defined mass which exudes a clear, viscid, honey-like fluid from its cut surfaces.2,3,6 Cytologic smears are often difficult to prepare because of the slimy consistency of the specimen and the relative lack of cells adhering to the slide. Histopathologic differentiation between myxosarcoma and myxoma may be difficult since differences between the two may be subtle.1–3,7 The malignant form tends to be more cellular, better vascularized and has nuclear pleomorphism and mitotic figures. Distinction between the benign and malignant form of the disease may be somewhat academic, since both myxoma and myxosarcoma are ill-defined, infiltrative growths in which recurrence after removal is highly possible.1,2,4,8 However, growth may be slow in some patients as borne out by several of the dogs in this report.9 Metastasis may occur with myxosarcoma but is rare,1,2,4 and was not detected in any of these five dogs.

Myxosarcomas in humans are rare, and arise primarily in the heart.10,11 Only three orbital myxosarcomas are reported.12–14 Benign myxomas are also uncommon and most often arise in the heart and in skeletal muscle. They may also occur in other soft tissues and in bone15 but only 11 myxomas involving the orbit in humans are recorded.8,16–20 Two types of myxoma are recognized: intramuscular (usually in the thigh) and, less commonly, juxta-articular (usually around the knee). In the intramuscular form, little or no cystic change is present whereas a characteristic feature of the juxta-articular form is the presence of dilated, cyst-like spaces filled with mucinous ground substance.21,22 In 65 humans with juxta-articular myxoma, 57 (88%) occurred around the knee, with a duration of symptoms ranging from 1 week to 18 years.23 Five tumors were incidental findings during hip or knee replacement surgery. In 29 patients, who were followed up after surgery, the lesion recurred at least once in 10 (34%). Although some of these lesions were found to abut synovial tissue and other periarticular soft tissues or to invade the joint itself, bone involvement was not described in any patient. These authors considered juxta-articular myxoma to be unquestionably benign and speculated that it might be a reactive process secondary to constant joint motion, rather than being neoplastic. A juxta-articular form of myxosarcoma has not been described in humans.

None of the human orbital myxosarcoma patients had cross-sectional imaging as they all predate the use of computed tomography (CT) and MR imaging, but one of the myxomas had cystic areas on ultrasonography.16 Also, the clinical description of a myxosarcoma of the orbit in a 6-year-old boy as a tense abscess suggested the presence of fluid pockets.14 The other tumors appear to have been solid, although most were described as being slippery, sticky, soft or friable. None of the human patients had any suggestion of involvement of the temporomandibular joint based either on clinical signs or imaging findings. Causes of orbital lesions with cystic components in man include dermoid cyst and other congenital anomalies which may present later in life: parasitic cyst, chronic hematic cysts (cholesterol granulomas), lymphangioma, lacrimal duct cyst, and mucocoele.24

Myxosarcomas and myxomas are rare in other animals except for chickens and rabbits in which they have a viral etiology.1,3 They have been reported in the horse, ox, sheep, dog, and cat3 and in several exotic species.25,26 Older animals are affected, with no breed or sex prevalence.3 In this series, the dogs were aged between 8 and 12 years old; two were male and three female. All were medium or large dogs. Myxomas are reported more frequently in dogs and myxosarcomas appear to be rare.27 Both tumors arise in connective tissue, and sites in which both myxomas and myxosarcomas have been seen in the dog include the skin and subcutis, heart, liver, mouth, limbs and spine, and as components of mixed mammary tumors.2–5,27–33 Myxosarcomas have also been reported in the intestine, spleen, mesentery, and urethra in dogs2,6,9,34–38 and two previous dogs with myxosarcoma involving the orbit have been described.39,40 During the time scale over which the five dogs reported here were seen, only one other myxosarcoma was diagnosed in our clinic, being on the paw of an 8-year-old Lakeland Terrier. This suggests that the orbit may be a predilection site for myxosarcoma in the dog.

A morphologically distinct entity of synovial myxoma was considered to be present in three dogs in which synovial tissue was involved in a myxoma.41 Two of these tumors arose at the stifle and one at the articular process joint of C2–3. A synovial myxoma involving the stifle of a dog has been reported32 and a synovial myxosarcoma has also been reported in this location.4 In both of these dogs, there was evidence of bone invasion. In another dog, a myxoma of the carpus was described as being attached to the antebrachiocarpal joint capsule by a stalk and to contain gelatinous, mucoid material on transection, and it is probable that this also represented a synovial variant.42 Possibly such synovial myxomas and myxosarcomas are equivalent to the juxta-articular form described in humans, similarities being their proximity to joints and the abundance of mucinous ground substance present. In the five dogs with orbital myxosarcoma described here, involvement of the temporomandibular joint was present or suspected in all five and pockets of fluid were also present in all five cases, being very extensive in four. These orbital myxosarcomas, therefore, also resemble the human juxta-articular form and may be equivalent to the synovial form described previously in dogs.41 The large size of the tumors in these dogs meant that biopsy was performed away from the temporomandibular joint in four and therefore lack of synovial tissue in the sample is not surprising. However, juxta-articular myxomas in humans are not reported to cause osteolysis whereas this has been seen in both myxomas and myxosarcomas arising near joints in dogs and suggests a more aggressive process. Detection of temporomandibular joint osteolysis may have implications for prognosis, because in this study, the dog with the most marked osteolysis also had severe pain on mouth-opening.

In the five dogs described here, exophthalmos had been present for periods varying between several weeks and 1 year before presentation. Two dogs also had soft, fluctuant swelling around the eye in which one was apparently acute in onset, and all five had varying degrees of swelling of the pterygopalatine fossa ventral to the orbit. Interestingly, although comparison with the opposite eye was not recorded, reduction in retropulsion was not a significant feature in these five dogs, presumably reflecting the fact that these orbital masses are soft and may contain large amounts of fluid. In none of the dogs was pain on retropulsion a feature of the disease, although one dog had marked discomfort on eating. Another dog also had severe bony involvement of the temporomandibular joint, but there were no associated clinical signs. One dog was blind in the affected eye.

Radiographic changes in the orbit suggest a poor prognosis as orbital disease must be extensive for this change to occur. In dogs where the tumor remains confined to the orbit, radiographs will be normal except for soft tissue swelling caused by displacement of the eyeball. However, false-negative radiographic results occur when extension of the tumor is present but is not severe enough to be radiographically evident.43 In this series, two dogs had osteolytic radiographic changes affecting the temporomandibular joint; thus, orbital myxosarcomas may involve this joint.

In this series, anechoic fluid pockets were readily identified in the four dogs that underwent ultrasonography and relative lack of internal echoes together with absence of pain suggested that abscessation was unlikely. In one dog, multiple, large, cystic areas with thick, echogenic borders were seen, and ultrasound guidance was used for aspiration of the contents. Although ultrasonography allowed identification of the cystic orbital lesion, it failed to allow determination of the extent of the mass in all dogs. Ultrasonographic results may, therefore, suggest an orbital myxosarcoma, especially if aspiration of the lesion yields tenacious fluid, but further imaging is required to assess its full extent.

MR imaging was performed in four of the five dogs described here and the extent of the solid and cystic components of the tumors, as well as larger areas of osteolysis, were readily apparent. The most helpful MR sequence was T2W because of the high contrast between fluid and soft tissue, which showed the loculated nature of the tumor. The fluid seen in the cystic areas was slightly hyperintense to CSF on T1W in all dogs, suggesting an increased protein content. In postcontrast T1W images, the extent of the solid component of the tumor could be evaluated, while a STIR sequence was used in the dog with the predominantly solid orbital mass and T2* gradient echo sequences were performed in three dogs to delineate the temporomandibular joint more clearly. Both cortical and medullary bone are hypointense on T2* gradient echo sequences which contrasts well with the hyperintense signal from adjacent soft tissues and permits assessment of osteolysis. All three orthogonal imaging planes were used and this was helpful in understanding the three-dimensional extent of the tumor. Although MR imaging was useful in detecting abnormal tissue adjacent to the temporomandibular joint in two dogs, definite osteolysis was not detected even using multiple imaging planes and sequences, and may have been overlooked.

CT has been used to assess orbital myxosarcoma in dogs,44,45 though contrast resolution of CT is inferior to that of MR imaging and CT is likely not to be as useful for tumor staging. In the five dogs described here, it is assumed that the large, fluid-filled pockets and areas of contrast-enhancing soft tissue would have been visible on CT images, but it is anticipated that the tumor margins would not have been as discernable.

Zygomatic sialocoele is the main differential diagnosis for an anechoic, cystic orbital mass in a dog, and was the initial diagnosis made in one dog based on ultrasonography and radiography alone. Zygomatic sialocoeles are uncommon and are usually the result of trauma.46,47 They give rise to exophthalmos, painless orbital swelling and protrusion of the oral mucosa behind the last molar tooth. Fluid in the sialocoele is usually a tenacious, straw-colored fluid not dissimilar to that found in myxosarcoma. A zygomatic sialogram may help to define the lesion and both CT and MR imaging are useful for discrimination.47 Other fluid-filled orbital masses in the dog include abscesses and hematomata, but it should be possible to differentiate these from sialocoeles and myxosarcomata on the basis of history, clinical signs, combined imaging findings, and fine needle aspiration.

In conclusion, myxosarcoma is a rare tumor in dogs but may have a predilection for the orbit. In view of the presence of fluid-filled pockets, which may be extensive, and the apparent involvement of the temporomandibular joints, the tumors described in this report are similar to the juxta-articular form of myxoma in man, albeit in a malignant form. It is possible that they arose from the temporomandibular joint and extended along fascial planes into the orbit, following a low-resistance pathway. Imaging features in these five dogs were of orbital masses with cystic components which were very extensive in four dogs and which were easily seen on ultrasonography. Temporomandibular joint osteolysis was visible radiographically in two dogs. MR imaging allowed evaluation of the full extent of the lesion and indicated that surgical drainage might be of benefit. Based on these five dogs, the clinical course of the disease may be rather indolent and relatively pain-free unless significant temporomandibular joint osteolysis is present. The main differential diagnosis is zygomatic sialocoele. Histologic diagnosis of myxosarcoma is not straightforward and may require surgical biopsy and special staining techniques. These are to be recommended in patients in which orbital fluid pockets extending to the temporomandibular joint are recognized on diagnostic imaging.

Footnotes

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I wish to acknowledge ophthalmology and pathology colleagues at the Animal Health Trust who were involved with these cases, especially David Donaldson and Claudia Hartley (ophthalmology), and Tony Blunden and Ken Smith (pathology).