Hepatozoon americanum: an emerging disease in the south-central/southeastern United States

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abstract

Objective – To review the clinical epidemiologic and pathophysiologic aspects of Hepatozoon americanum infection in dogs.

Data Sources – Data from veterinary literature were reviewed through Medline and CAB as well as manual search of references listed in articles pertaining to American canine hepatozoonosis.

Veterinary Data Synthesis – H. americanum is an emerging disease in endemic areas of the United States. It is vital that practitioners in these areas become familiar with the clinical syndrome of hepatozoonosis and the diagnostic modalities that can be utilized to document the presence of infection. Additionally, veterinarians must understand the epidemiology of the disease in order to better prevent infections in their veterinary patients. Recent data have been published that shed new light on transmission of H. americanum to dogs; however, much remains unknown regarding patterns of infection and the natural vertebrate host source.

Conclusions – While the prognosis for untreated H. americanum remains poor, for patients in which the disease is recognized and properly treated the outcome is favorable. Understanding the complex life cycle, numerous clinical symptoms, and treatment protocol will assist veterinarians who are treating patients with hepatozoonosis.

Introduction

In endemic areas, tick-borne diseases can be a common cause of acute illness in dogs presenting to emergency/critical care facilities. Although doxycycline is an effective treatment for many tick-borne diseases, it is ineffective in treating protozoal diseases such as hepatozoonosis. Hepatozoon americanum is an emerging disease in the south-central and southeastern United States that can cause high fever, leukocytosis, hypoglycemia, musculoskeletal pain, and gait abnormalities. Veterinarians unfamiliar with H. americanum have performed extensive diagnostic testing searching for a septic focus (as an explanation for the presenting signs) including blood cultures, abdominal radiography, abdominal ultrasonography, thoracic radiography, and even exploratory laparotomy. Emergency and critical care veterinarians should be familiar with the geographic location, presenting history and clinical signs, life cycle, radiographic findings, expected clinicopathologic abnormalities, and available diagnostic testing in order to properly identify and effectively treat cases of H. americanum.

Hepatozoonosis is an arthropod-borne infection that affects numerous species including amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals.1 Numerous species of Hepatozoon have been reported to encompass a broad range of clinical disease in both wild and domestic animals. The clinical syndrome of the different species of hepatozoonosis varies, however, all share a common life cycle. This includes sexual development and sporogony within a hematophagous arthropod vector, followed by transmission to a vertebrate host and asexual development with merogony and gamontogony.1 The first Hepatozoon species in domestic dogs, initially described in 1905 in India, was reported to cause mild disease characterized by anemia and lethargy. The organism was first named Leukocytozoon canis2 and was later renamed Hepatozoon canis.3,4 Current research has characterized 2 distinct species of Hepatozoon transmitted by tick-borne vectors that utilize domestic dogs as an intermediate host, and can result in clinical disease. H. canis has been reported in dogs worldwide, including Japan,5 Africa,6 the Middle East,7 Spain,8 France,9 Italy,10 Greece,11 Brazil,12 Thailand,13 and the Phillippines.14H. canis typically results in mild clinical disease, however, infections can range in severity from asymptomatic to severe life-threatening illness depending on the parasite burden.15 While all canine infections were initially attributed to H. canis, in 1997 a novel species was identified in dogs in the United States. H. americanum was detected and characterized in dogs in the southern United States and determined to be unique based on the tissue stages, host tick vector, clinical syndrome, and genetic and antigenic characteristics.16,17 Contrary to H. canis infection, H. americanum typically results in a severe debilitating course of illness which, in the absence of treatment, is usually fatal.18

Pathogen Characteristics

Hepatozoonosis is a protozoal infection and is classified among the apicomplexan phylum, a group of protozoal parasites that encompasses a number of clinically significant parasitic pathogens, including Eimeria, Isospora, Toxoplasma, Babesia, Plasmodium, and Cryptosporidium among others. Hepatozoonosis is further characterized to the family Hepatozoidae, suborder Adeleorina.19 While >300 species of Hepatozoon have been identified, many of these are known to infect lower vertebrates and invertebrates.1 Approximately 50 Hepatozoon species have been described in mammals, and among these are 2 that are known to infect domestic dogs, H. canis, and H. americanum. Both the clinical syndromes and the tissue target of individual Hepatozoon species varies. While the Hepatozoon spp. affecting nonmammalian animals such as reptiles, birds, and amphibians commonly produce gametocytes in erythrocyte cell lines, in mammalians, the cell line most often affected is the leukocyte.15

The most common tissue target for development of H. americanum in domestic dogs is striated muscle, including both skeletal and cardiac muscle.17,20–22 The pathologic changes observed include cysts, meronts, and pyogranulomatous inflammation in skeletal and cardiac muscle. In addition, most dogs with active disease will have evidence of periosteal proliferation thought to be secondary to inflammation within the local skeletal muscle attachments.23 Vascular changes may be seen as well, including fibrinoid degeneration of vessel walls, and mineralization, intimal proliferation, and pyogranulomatous vasculitis. Tissue injury may also occur during the development of antibodies and immune complex deposition.24

Geographic Distribution and Transmission

H. americanum has a narrow invertebrate host range and appears to be limited to Amblyomma maculatum, the Gulf Coast tick.25,26 Experimental attempts to transmit H. americanum using other tick species, including Dermacentor variabilis, and Amblyomma americanum have been unsuccessful.26 Experimental transmission of H. americanum via the brown dog tick has had limited success with 1 report of successful infection of Rhipicephalis sanguineus.27 As a result, the geographic range of hepatozoonosis has been limited to areas where A. maculatum is present. Initially this range was limited to the southern United States; however, recent evidence supports the possibility that the range of A. maculatum is expanding as far north as Kansas, and Kentucky.24,28,29 The primary vertebrate host of H. americanum is unknown, however, it is unlikely that domestic dogs are the primary host. Although 40% of coyotes tested in 1 endemic area were positive for H. americanum30 field surveys evaluating vertebrate hosts of Gulf Coast ticks indicate neither domestic nor wild dogs are the preferred host for any of the feeding stages of these ticks.31 The primary mode of transmission of H. americanum to dogs is through ingestion of the infected tick. Experimentally infected larval ticks will carry the infection into the nymph stage, and adult stage ticks that have acquired the infection at the nymph stage are also infectious to dogs.25 This transstadial transmission allows for a wider range of potential vertebrate hosts. Larval and nymphal ticks preferentially feed on small mammals such as rodents, and also on ground-dwelling birds. Domestic dogs could acquire the infection both through ingestion of adult ticks during self-grooming or by predation of rodents or birds harboring the larval or nymphal ticks. This expanded host population may be a contributing factor in the maintenance of endemic populations of reservoir vertebrate hosts allowing for continued transmission to domestic dogs. In utero transmission from dam to puppies has not been documented with H. americanum, although this mode of transmission is likely to occur as it has been reported in H. canis infection.24 Predation of animals harboring the tissue stages of the organism has been documented to result in infection in other Hepatozoon species but until recently this mode of transmission had not been documented with H. americanum. Johnson et al32 documented the existence of cystozoite stages of H. americanum. This work led to documentation of experimental infection in previously H. americanum-free dogs fed H. americanum cystozoites from experimentally infected rodents. Recent work has also confirmed H. americanum infection in dogs fed prey harboring infected A. maculatum or containing cystozoites of H. americanum in their tissues indicating these modes of transmission of H. americanum further verifying that predation is important in transmission of H. americanum in dogs.33

Life Cycle

The typical life cycle of H. americanum in dogs begins with the ingestion of mature H. americanum polysporocystic oocysts contained within the hemocele of an infected host tick.4 Once ingested, sporozoites are rapidly freed from the sporocyst within the small intestine of the dog. These sporozoites are thought to be taken up by host macrophages and migrate hematogenously or via lymphatics to skeletal or cardiac muscle target tissues and are lodged between muscle fibers. The affected host cell, identified as a macrophage,34 will then produce concentric layers of a mucopolysaccharide material that is deposited around the cyst,4,24 forming the classic onion skin lesion.22,35 The encysted organism then undergoes asexual reproduction though merogony in which the organism increases in size and the nucleus and other organelles divide repeatedly. The result is the development of multiple merozoites that are contained within the meront.24,36 Mature merozoites are freed when the cyst is ruptured, resulting in a severe local inflammatory response that initially consists of predominantly neutrophils, followed rapidly by macrophages and pyogranulomatous inflammation. These merozoites can be taken up by macrophages and enter the local vasculature to develop into gamonts in circulating monocytes, or can be recycled and undergo repeated merogonic cycles in the tissue.4,24,36 The gamonts circulating within leukocytes can then be taken up by ticks feeding on the parasitized vertebrate. The gamonts are released from the leukocytes within the gut of the tick and will undergo sexual reproduction, or gametogenesis. Fertilization then occurs followed by division of the zygote and the formation of oocysts that are released into the tick hemocele. The oocysts encapsulate hundreds of sporocysts that contain the infective sporozoites. The sporozoites are retained within the tick's hemocele and must be ingested in order to infect the vertebrate host.24 One infected tick can contain thousands of infective sporozoites. Each one can eventually produce a tremendous number of merozoites safely hidden in a cystic structure until they are released causing recurrent fever, muscle pain, and chronic muscle wasting.

Clinical Findings of Hepatozoon americanum in Dogs

Symptoms

H. americanum infections are often severe, debilitating, and can be fatal. The clinical signs include fever that is unresponsive to antimicrobial therapy, mucopurulent ocular discharge, generalized bone and muscle pain, and lameness. The lameness and gait abnormalities can range from stiffness to total recumbency. Most dogs will continue to eat, however, chronic weight loss and cachexia are often noted due to the presence of increased caloric demands of the inflammatory state, and concurrent muscle atrophy.24 The symptoms of H. americanum infection are the result of the rupture of merozoites encysted within striated muscle and the subsequent intense inflammatory response. This inflammatory response is accompanied by localized angiogenesis and the formation of a vascularized pyogranulomatous lesion.18 The clinical signs are consistent in most affected animals, however, the disease can follow a chronic course and the clinical signs will often wax and wane. Occasionally ocular lesions including papilledema, uveitis, retinal scarring, and hyperpigmentation are noted on ophthalmic exam.37 Mucopurulent ocular discharge is almost always present in affected animals secondary to inflammation of the extraocular muscles and decreased tear production (Figure 1). Chronic infections can result in symptoms of renal disease including polyuria and polydipsia, secondary to renal amyloid deposition, or immunoproliferative glomerulonephritis with protein-losing nephropathy. In the absence of treatment, the disease will continue to progress and will usually lead to death within 12 months.24

Mucopurulent ocular discharge and muscle atrophy in a dog with Hepatozoon americanum infection.

Clinicopathologic findings

One of the most consistent features of H. americanum is a persistent leukocytosis that can range from 20 to 200 × 109/L.24,38 with the majority of the cells being mature neutrophils. In contrast to H. canis infections, H. americanum infections are rarely diagnosed through demonstration of intracellular gamonts on peripheral blood smears due to the low levels of parasitemia; found in <0.1% of circulating leukocytes,17 and poor stain uptake of parasites.39 Other findings on the hemogram include mild normocytic normochromic nonregenerative anemia associated with the presence of chronic disease and chronic inflammation. Platelet counts can be variable, but normal to elevated platelet counts are typically reported. Thrombocytopenia is uncommon and a finding of a low platelet count may indicate the presence of concurrent tick-borne infection such as ehrlichiosis or Rocky Mountain spotted fever.24

A common finding on biochemical analysis includes elevation in serum alkaline phosphatase. This feature is thought to be related to the occurrence of a periosteal reaction secondary to myositis.24,36 Hypoglycemia, when present, can be seen in patients with significant elevation in white blood cell counts. The presence of high numbers of white blood cells will lead to postcollection metabolism of glucose, causing an in vitro rather than in vivo effect. While this effect can exaggerate hypoglycemia, dextrose supplementation is still recommended to treat hypoglycemic animals in the authors' opinion. Postcollection glucose metabolism can be negated through the use of sodium fluoride blood collection tubes, which will prevent the metabolism of glucose by cells.24,40 Decreased serum albumin can be seen as a consequence of chronic inflammation, decreased protein intake, and altered protein metabolism associated with the production of acute phase proteins and macroglobulins. A secondary effect of reduced protein intake and altered protein metabolism is decreased serum urea values which can be seen in those dogs not suffering from renal damage. In spite of the presence of often severe myositis and pyogranulomatous inflammation, creatine kinase activity is usually within the reference interval.

Urinalysis is often normal, although patients with chronic disease and symptoms of protein-losing nephropathy can have decreased concentrating ability resulting in isosthenuria (urine specific gravity 1.008–1.012) and proteinuria with an elevated urine protein-creatinine ratio.24

Imaging features

Periosteal bony proliferation is a frequent finding on radiographs of dogs infected with H. americanum. This finding is thought to be secondary to pyogranulomatous myositis and commonly occurs at the sites of muscle attachment to bone. While not all affected dogs will display these radiographic signs, bony changes have been reported in both long and flat bones.20,24 The osseous changes seen with H. americanum are similar both radiographically and histologically to hypertrophic osteopathy showing periosteal proliferation and an absence of cortical bone destruction41 (Figure 2).

Radiographs will commonly reveal a classic periosteal reaction secondary to local pyogranulomatous inflammation.

Nuclear scintigraphy has been utilized to characterize the onset and location of skeletal lesions in experimentally infected dogs. Changes were detected in 6 affected dogs with an onset of lesions occurring between 35 and 67 days after experimental infection, consisting of diffuse, bilaterally symmetric, homogenous, high intensity radiopharmaceutical uptake.41

Pathologic findings

Many of the gross lesions of hepatozoonosis are consistent with any chronic disease process, including poor body condition, cachexia, and reduced skeletal muscle mass.4,24 Most dogs with active disease will exhibit characteristic periosteal lesions including disseminated and symmetrical periosteal proliferation.4,23,24 The lesions are typically found in the diaphysis of the proximal long bones, however flat and irregular bones can be affected as well.20 Histopathologic lesions are most commonly located within striated muscle (both cardiac and skeletal) as this is the site of merogony.4,23,24 Marked pyogranulomatous myositis can be visualized microscopically and is found in numerous tissue sites including adipose and connective tissue. Lymphatic, splenic, hepatic, pancreatic, and pulmonary tissues are less frequently affected. Additional histopathologic findings may include membranous glomerulopathy, amyloidosis, and lymphoplasmacytyic synovitis.22,42,43

Diagnosis

Identification of intracellular gamonts

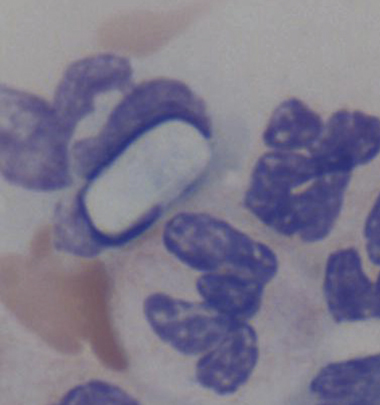

Diagnosis of H. americanum infection by detection of gamont-infected cells in a peripheral blood smear using Romanowski stains is uncommon as mentioned previously due to low levels of parasitemia.17,39 Gamonts will appear as basophilic oval shaped cytoplasmic inclusions and are typically found in less than 0.1% of circulating monocytes or neutrophils (Figure 3). Examination of buffy-coat preparations may increase the likelihood of detecting infected leukocytes.24

Gamonts are rarely noted on blood smear and will appear as oval-shaped cytoplasmic inclusions within neutrophils or monocytes (× 100 magnification Wrights stain).

Muscle biopsy

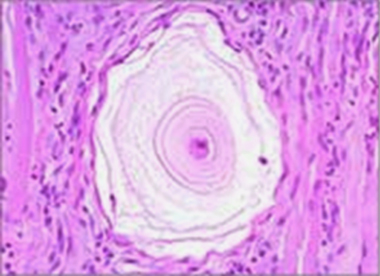

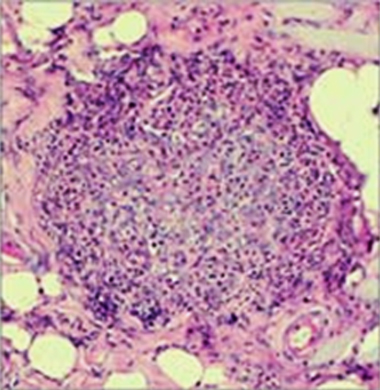

Muscle biopsy has been utilized as a confirmatory test for diagnosis of H. americanum in infected dogs. Conventionally, multiple biopsies are acquired from the biceps femoris or the semitendinosis muscle and preserved in formalin.38 Evaluation of multiple biopsies is recommended, however false negative results from muscle biopsy evaluation are rare owing to high numbers of organisms in the skeletal muscle of infected dogs.24 Classic lesions are described as onion skin cysts (Figure 4), which are concentric layers of a mucopolysaccharide material surrounding a parasitized host cell resulting in the formation of a large cystic structure situated between skeletal muscle fibers. In addition to intact cysts, ruptured cysts with the release of free merozoites will stimulate intense pyogranulomatous inflammation (Figure 5). The resultant granuloma will contain inflammatory cells and many intracellular parasites.21

Onion skin cysts found on histopathologic section of skeletal muscle in a dog with hepatozoonosis (× 40 magnification hematoxylin and eosin stain).

Pyogranulomatous inflammation found on biopsy of skeletal muscle of a dog infected with Hepatozoon americanum (× 40 magnification hematoxylin and eosin stain).

Serology

An indirect ELISA has been developed for identification of H. americanum in dogs. One limitation of this test has been the inability to fully clear residual tick tissue from the test antigen, resulting in false positives in dogs where exposure to Amblyomma ticks is common.23 Currently, this test is performed at Oklahoma State University; however, it is not available commercially to practitioners.36

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Recently a real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test was developed by researchers at Auburn University. The technique amplifies a fragment of H. americanum 18S rDNA and is able to detect as few as 7 copies of the genome per milliliter of blood. The quantitative PCR is performed on whole blood collected into ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid anticoagulant and is commercially available.34

Treatment of Hepatozoon americanum

Initial stabilization of severely affected animals includes the application of supportive care and should be targeted at correcting life-threatening problems. Affected dogs can be presented with severe cahchexia, dehydration, hypoproteinemia and hypoglycemia. These symptoms can be addressed with the administration of crystalloid and colloid fluid therapy and dextrose supplementation. Nutritional support may be necessary in those animals that are unable or unwilling to eat and can be provided in the form of enteral or parenteral nutrition depending on the specific patient needs.

Currently there are no medications that are effective at completely eliminating the tissue stages of the organism. A protocol for treatment of overt disease has been developed and involves the combination of trimethoprim-sulfadiazine (15 mg/kg, PO, q 12 h), clindamycin (10 mg/kg, PO, q 8 h), and pyrimethamine (0.25 mg/kg, PO, q 24 h) (TCP protocol) for 2 weeks followed by chronic administration of the anticoccidial drug decoquinate.18,23 The administration of the TCP combination is effective in eliminating the merozoite stage, thereby removing the stimulus for pyogranulomatous inflammation. This treatment is followed by a remission phase, the duration of which lasts until enough asexual reproductive cycles are completed to induce an inflammatory response and a return of clinical disease. Depending on the parasite load, relapse usually occurs within 1–6 months.41 Decoquinate, a quinilone anticoccidial agent, is utilized to arrest the development of H. americanum merozoites as they are released from the mature meronts. Previous recommendations included administration of decoquinate at a dose of 15 mg/kg mixed in food twice daily for 2 years18,24,39 although with the availability of PCR testing it is possible that the drug may be discontinued once clinical signs are resolved and a negative PCR result is obtained.36 After 14–21 days on the TCP protocol, decoquinate should be administered daily with PCR testing every 3–6 months until negative status is reached. Decoquinate is very safe for long-term use, and some dogs have been asympotomatic while receiving the drug for over 5 years.18

Relapses are less common when utilizing the previously described TCP protocol, however, they can still occur as none of the aforementioned drugs are effective at eliminating encysted meronts in tissue. When relapses do occur the TCP protocol is repeated followed again by chronic decoquinate therapy. In both acute and chronic infections, palliative therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is recommended to alleviate discomfort.4,24

Prevention

Environmental control of the invertebrate vector, the tick, is important in disease prevention, particularly in endemic areas. Application of acaricides and tick repellants is also effective at preventing the ingestion of the infected tick host and will assist in limiting the spread of disease. Transmission of H. americanum through predation of infected vertebrates has been confirmed experimentally although this mechanism has not been verified in the natural environment. Dogs should not be fed raw meats or consume organs from wildlife to avoid this possible mechanism of transmission.24

Summary

H. americanum is an emerging disease that is becoming more common in endemic areas as the reservoir of ground-dwelling rodents expands and the geographic distribution of the Gulf Coast tick increases. Clinicians must recognize the signs of disease and confirm the diagnosis without delay so that appropriate therapy can be initiated and unnecessary testing is avoided. The prognosis for dogs that receive early diagnosis and treatment is excellent, although long-term administration of decoquinate is needed to prevent reinfection from developing organisms in tissue cysts. If diagnosis and treatment are delayed however, the dog is more likely to develop severe disease, with secondary complications such as severe muscle wasting and protein-losing nephropathy, and the prognosis becomes guarded to poor.