Strategy-Structure Alignment in the World Coffee Industry: The Case of Cooxupé

Abstract

This case discusses the evolution and challenges of Cooxupé—a coffee marketing cooperative in Brazil. Founded in 1954 by twenty-four producers, Cooxupé experienced significant growth since 1990 as a result of direct export efforts implemented by Joaquim, the Export Director. Yet Cooxupé leaders face increasing challenges ahead. The world coffee industry has evolved in such a way that growth is deemed essential for survival. The growth imperative poses additional challenges to Cooxupé. First, it becomes more difficult to originate coffees with the quality consistency expected by clients. Second, the increased size and heterogeneity of the membership may have negative impacts on cohesion. Third, financial constraints create the need to evaluate and possibly change the cooperative ownership structure.

It was dusk of a cool winter day in 2006 when Joaquim Libânio Ferreira Leite—the Export Director of Cooxupé—was driving along the rolling hills of southeastern Minas Gerais, Brazil. Joaquim had just arrived from another business trip to visit coffee buyers in Europe and the long journey home allowed him to take stock of the cooperative's evolution and challenges. Founded in 1954 by twenty-four coffee producers, Cooxupé was the largest coffee marketing farmer-owned cooperative in the world. In 2005, it had more than 10,000 producer-members and generated sales of R$1.2 billion. Recent growth was largely based on direct green coffee export sales to more than 150 buyers in thirty countries.

A great deal of change was going on in the world coffee market. World prices were at historic lows because of considerable supply growth, especially in Brazil and Vietnam. Additionally, the Brazilian currency, the real, had strengthened significantly since 2003. A strong balance sheet and internal cash flow were necessary to ensure against volatility in world coffee markets. Earnings from the cooperative were retained to provide new equity for growth as cooperatives are not allowed to issue financial securities in Brazil. Low coffee prices were approaching production costs in 2006, suggesting a margin squeeze and pressure on earnings.

As he was about to reach his home, Joaquim pondered about Cooxupé's main challenges for the future. Given the competitive forces in the world coffee industry, it was imperative that Cooxupé continued to grow to remain a viable player. But what growth strategies should the cooperative pursue? In addition, these growth strategies should be able to enhance members' income as Cooxupé is a member-owned and -controlled organization. Another daunting challenge was to identify mechanisms to strengthen the relationship with a growing and increasingly diverse membership. And, finally, Cooxupé's leaders would need to find new ways to acquire risk capital to finance growth.

The World Coffee Industry

Coffee is one of the world's most valuable “soft” commodities and among the largest food import in many developed countries. There are two different species of coffee. Arabica coffee beans are used for higher-grade coffee and account for 60% of total world production. Robusta is a lower-grade coffee with a neutral flavor and stronger caffeine content. Robusta coffee beans are grown at lower altitudes and are more resilient to disease and weather, while Arabica coffee beans are usually grown at higher elevations and mature more slowly. Arabica coffee bean production is concentrated in South and Central America and East Africa, while Robusta coffee bean production is concentrated in Asia and South America. Brazil is the only major exporting country to produce both Arabica and Robusta coffee beans.

Even though Robusta and Arabica coffees have different characteristics, their markets are highly interdependent because processors (or roasters) use both types of coffees in their blends. Robusta is normally used as “filler” in coffee blends—as it has a neutral flavor—with Arabica beans originated from different regions giving the coffee blend its distinctive attributes in terms of aroma, body, and flavor. Another distinguishing characteristic between Arabica and Robusta is that “defects” due to improper harvesting and handling of coffee beans (see details below) in Robusta may be corrected by means of new processing technologies such as “steaming.” In other words, whenever a Robusta bean is not properly harvested or handled, which creates a harsher or sour flavor, steaming is used to wash out undesired tastes. For Arabica beans, postharvest handling operations at the farm and quality segregation and grading by the marketer (cooperative or trader) are substantially more important to preserve the desired coffee bean attributes valued by roasters.

Production and Processing of Coffee Beans

The global supply chain for coffee involves producers, middlemen, exporters, importers, processors (or roasters), and retailers. The cultivation of coffee beans is a time consuming and labor intensive process. Although production advancements have been made, most of the 25 million coffee farmers work in small family farms (with less than 6 hectares) without access to information on improved cultivation techniques and market conditions. In larger, wealthier coffee-producing countries such as Brazil and Colombia, farmers are organized into cooperatives that provide and share information and resources for improving production and marketing decisions.

Coffee is grown on trees that thrive in tropical and subtropical climates, usually 1,000 miles from the equator or less and at altitudes of up to 7,000 feet above sea level. Coffee trees begin their lives in a nursery and are transplanted to farms about a year later. The coffee tree then matures for another four to five years before it begins its annual cycle of production, starting as small white flowers and developing into small green cherries. The green cherries ripen into a deep red color inside of which are two coffee seeds. These seeds are eventually used to plant more coffee trees or processed into green coffee beans that are later roasted and ground into coffee ready to be brewed.

Once coffee cherries are red and ripe, a series of processing events takes place before the green coffee beans are moved to the next stage of the commodity value chain. The manual labor needed for these processing events is intensive. Coffee beans must first be harvested from the trees. Harvesting is done by hand in an effort that can require up to seven gathering cycles since not all coffee cherries ripen at the same time. In large, commercial farms located in relatively flat land, mechanical harvesters are increasingly used to harvest the crop. Most specialty coffees are picked exclusively by hand and are only taken from the middle part of the crop for the highest quality of bean.

In addition to genetics and cultivation techniques, coffee quality is largely dependent on postharvest handling, which differs significantly across countries. In Brazil, coffee plantations are located in subtropical areas with no marked rainy seasons. As a result, coffee trees usually present several flowerings during spring and thus coffee beans mature at different times in the fall. Since harvesting is carried out once a year to save costs—coffee harvesting is the most expensive item in total production costs—cherry beans are harvested along with unripe (café verde) and dried (café seco) beans. Producer and cooperatives that subsequently segregate beans into more uniform lots tend to capture a quality premium in the marketplace.

Following harvest, the producer needs to perform several coffee-handling operations (known as beneficiamento) before shipping the coffee to a cooperative or warehouse where it will be further prepared and marketed. These coffee-handling operations include separating impurities from the coffee beans, drying, de-pulping, and bagging. Brazilian coffees are first dried under the sun in patios (terreiros) and subsequently in driers before being depulped. This process is known as the “dry method” because coffee beans are not washed and fermented. The Brazilian coffee is thus known as “natural” to distinguish it from the “washed” coffees produced in Colombia and elsewhere. Exporters also perform a series of preparation activities, including finer impurity separation and selection of coffee beans based on color, size, and cup testing.

Supply and Demand Drivers

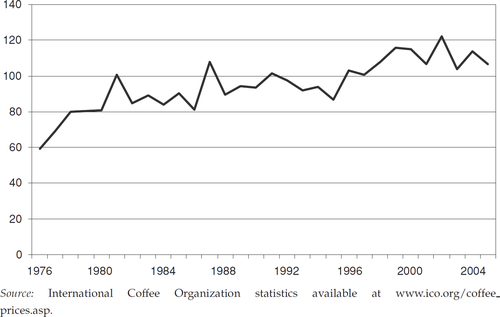

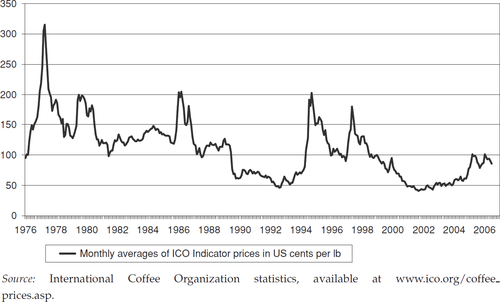

In 1962, sixty-six countries created the International Coffee Agreement (ICA). The agreement set an export quota on each coffee-exporting national to restrict coffee trade. The result was an increase and stabilization of international coffee prices. However, the ICA disintegrated in 1989. With no controls over supply, the coffee industry saw a large production boom. The world's two largest coffee-producing countries, Brazil and Vietnam, drastically increased production in the late 1990s (figure 1), which depressed world prices. Taking inflation into account, the real price of coffee beans has fallen to just 25% of the 1960s level (figure 2).

Industry consultants estimated that the price of coffee in the early 2000s did not cover production costs of growers. Producers, however, have pressure to maintain quality and production despite minimal earnings or losses because the roaster's cost of switching suppliers is low. With billions of coffee drinkers and a handful of companies controlling the international coffee market, producers have little bargaining power.

Growth of world coffee production (in millions of 60 kg bags)

Average nominal prices received by coffee producers (U.S. cents/pound)

In addition to the end of the ICA and subsequent supply growth, many industry analysts argued that coffee industry consolidation has increased price spreads between the retail and farm gate levels of the value chain. According to International Coffee Organization (ICO) data (2006), producer countries earned USD 10 billion from a coffee market valued at about USD 30 billion in 1993. A decade later, they received less than USD 6 billion of export earnings from a market that has more than doubled in size. This resulted in a drop in the producers' share from over 30% of the market to less than 10%.

Four main roasters—Nestlé, Kraft, Sara Lee, and Procter & Gamble—buy about half of total world production and dominate coffee retail markets. For example, the three largest U.S. coffee marketers are Procter & Gamble, Kraft, and Nestlé. These firms accounted for about 33%, 28%, and 8% of the U.S. coffee market in 2003. Their widely recognized brands include Maxwell House, Folgers, and Nescafé, which command significant premiums over the actual cost of the coffee they sell. In addition, the ability to use coffee beans from different sources to adjust their blends gives the roasters even more buying flexibility.

The United States, Germany, Japan, France, and Italy consume more than half of the world total coffee exports. The world market for coffee has increased as more consumers began drinking coffee in other countries. There is a positive relationship between average income and coffee consumption in that consumers in higher-income countries drink more coffee. However, coffee consumption in developed countries has declined. U.S. coffee consumption, for example, is about half of what it was in 1945 on a per capita basis.

The world coffee market is experiencing shifts in demand at opposite ends of the product spectrum. An increase in the demand for low-grade, low-cost Robusta coffee reflects new processing technologies that remove the harsh taste of the typically low-quality beans. Coffee roasters are now able to buy low-quality coffee beans at very low cost and produce their coffee blends with the same level of quality. On the other end, demand for premium, specialty or gourmet coffees is also on the rise. For example, specialty coffee sales more than quadrupled in the United States since 1990. Specialty coffee marketers developed gourmet coffee blends and flavors that appealed to young coffee drinkers. These firms pay close attention to the quality of the coffee bean, in addition to its origin and how it was harvested and processed. These specialty coffee marketers also developed unique roasts and grinds that appealed to a premium coffee market. The growth of the specialty coffee segment suggests emerging opportunities to coffee producers. Specialty coffee is often imported with quality premiums over commodity prices, which vary according to the origin, coffee bean quality attributes, and the production process.

Cooxupé: Roots and Evolution

Cooxupé (Cooperativa Regional de Cafeicultores em Guaxupé Ltda.) was formed in 1957 by 24 coffee producers. According to Isaac Ferreira Leite—one of the founders and first President of Cooxupé—a cooperative is a suitable organizational structure for individuals to solve common problems. In the case of coffee producers in Guaxupé, located 300 km north of São Paulo city, the common problem was dependence on coffee buyers (intermediaries, dealers, and exporters) and lack of fair value for their commodity. The idea to form a cooperative came from Dr. Isaac. His motto was “trust and work.”

Cooxupé was first headquartered in a small country store that sold farm inputs to members. In March 1965, Cooxupé acquired a coffee warehouse with storage capacity for 200,000 bags of coffee. The warehouse built in 1929 was owned by CASEMG (an agency of Minas Gerais state). As the cooperative did not have enough capital to buy the warehouse, Dr. Isaac arranged a financing agreement with the Brazilian Coffee Institute (IBC).1 The warehouse purchase was an important milestone because without it coffee producers had to sell coffee immediately after harvest at very low prices as they did not have enough storage space on farms. With the acquisition of the cooperative warehouse coffee producers could wait for the best market conditions to sell.

In acquiring the warehouse Cooxupé entered the coffee marketing business. Cooxupé leaders made a decision to provide members “total flexibility” to market their coffee. First, the cooperative would be a provider of storage and marketing services and would not take title of the delivered coffee. It was the members' decision when to sell the coffee. Differently from competing cooperatives and private traders, the cooperative would provide “full liquidity” to members as it would always purchase coffee upon a member's sell order. In addition, the cooperative would not require member loyalty and members would not have to store all their coffee in the cooperative warehouse and thus could market (all or part of) their coffee with competitors. According to Cooxupé leaders, the full liquidity policy was instrumental in building trust with members especially when prices were low.

At that time, the cooperative created a coffee marketing unit that would sell the coffee to domestic roasters, dealers, and exporters. Cooxupé did not engage in direct export activities during this time. From the start, Cooxupé adopted the cooperative principles of democratic control, service at cost, and limited return to members' capital. In fact, Cooxupé had a policy of reinvesting all net income to build a strong equity capital base. The cooperative's net income would be retained as non-allocated reserves (i.e., retained earnings) to increase the equity capital needed to fund business growth.

Dr. Isaac's vision was that the cooperative would have to balance traditional cooperative principles with an entrepreneurial spirit. He believed that for the cooperative to succeed it would have to be run as efficiently as a for-profit business. Differently from other cooperatives in Brazil, Cooxupé's management would be professional. In other words, members and elected officials would not have executive responsibilities. Members elected nine directors to the cooperative Board—following the democratic principle of one member, one vote. The Board then elected the President and a Vice-President who nominated an Executive Director appointed by the Board of Directors. The main management functions such as administration, warehousing, finance, and marketing were run by hired professionals.

Another important development during Dr. Isaac's tenancy was geographical diversification with mergers and acquisitions and the development of regional warehouses. Between 1977 and 1990, Cooxupé acquired five coffee cooperatives in the states of Minas Gerais and São Paulo. Such acquisitions were very uncommon in Brazil. It also established regional centers—called núcleos—including coffee warehouses and country stores to source coffee from other important coffee-producing regions.

Direct Coffee Exports

Until the late 1980s, when the International Coffee Agreement was discontinued, coffee exports were under control of a quota system. Under this agreement, coffee producers were allocated export quotas based on their historical export volume and coffee inventories. In Brazil, each exporter had its own coffee export quota also based on historical volume that was strictly enforced by the Brazilian Coffee Institute (IBC). At that time, private traders and dealers controlled Brazil's coffee exports. However, the major exporters had little incentives to invest in quality differentiation because they enjoyed stable margins under the protection of the quota system. They focused on originating coffees from different regions at the lowest possible cost and comingled them to export. As a result, Brazil earned a reputation especially in the United States for delivering low-quality and high-variance green coffee.

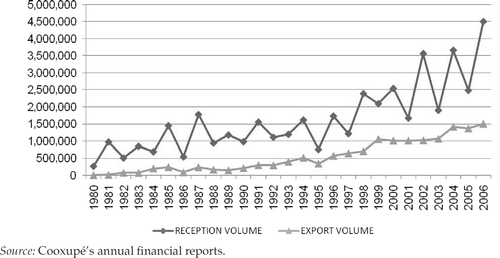

In 1982 coffee cooperatives were granted 8% of the total national export quota as a result of successful lobby efforts by the National Coffee Council.2 This breakthrough created an opportunity for Cooxupé to develop its own direct coffee export strategy. Dr. Isaac believed that to enhance the value of members' coffee, Cooxupé would have to build direct relationships with coffee importers and roasters in major import markets. It would have to learn their specific coffee quality needs and develop a reputation for coffee quality, consistency, and volume. These efforts were the responsibility of Dr. Isaac's son, Joaquim, who became the cooperative Export Director. Since the early 1980s, direct annual exports grew to almost 1.4 million bags of coffee, equivalent to R$460 million or 30% of total revenues. During the same period, the volume of coffee received from members increased from 270,000 bags in 1980 to 2.5 million in 2005 (figure 3).

According to Joaquim, Cooxupé's coffee export efforts were successful for two reasons. First, Cooxupé had developed standards and a grading system specifically for Southern Minas producers since its foundation. Differently from private exporters originating and comingling coffees from different regions, Cooxupé focused on a classification system that would provide standard quality grades for coffee produced in a specific origin—Southern Minas.3 By the time Cooxupé started to export coffee directly to buyers in Europe in the 1980s, its coffee quality standards were already established as a reference by market participants. Second, consistency and volume were also deemed as necessary conditions for success in export markets. By developing a grading system specific to Southern Minas coffees and working hard to guarantee quality consistency over the years in large enough volumes, coffee buyers, and roasters increasingly used Cooxupé originated coffees in their blends. In other words, with quality standards, consistency, and volume Cooxupé earned trust and respect in export markets as a reliable coffee supplier.

Cooxupé: coffee bags received and direct coffee exports (1980–2006)

Initially, Cooxupé developed an export agreement with a private bank (Comind) that had a coffee trading division and access to buyers in Europe. The agreement allowed Cooxupé to export with its name in the coffee bags thereby building brand awareness among buyers.4 In 1983, Cooxupé hired Saul Eliezer, a coffee quality expert from a large private exporter, who would be in charge of the cooperative export office in Santos, Brazil's largest port. In order to build knowledge and relationships with buyers, Joaquim moved to Hamburg, Germany in 1984. Using the IBC office network in Europe, he was able to contact and develop relationships with major buyers in the continent. In 1985 he returned to Brazil as the Export Director of IBC. In 1987, his office was moved to London and in 1990 he became the Brazilian representative at the International Coffee Organization. During this time, Joaquim visited all coffee producing countries and developed personal relationships with the main coffee roasters and importers. At the end of 1990, he moved back to Brazil and took the Export Director position at Cooxupé. At that time, Cooxupé was exporting an average of 200,000 coffee bags per year.

When Eliezer retired, Joaquim hired Justino Gonzaga from another large private exporter to run the Santos office. While Gonzaga dealt with all the export processes at the port, Joaquim continued to develop relationships with buyers. His export strategy was to always deliver coffees that surpassed the client's expectations and also to follow up with postsales service efforts. He visited his major clients at least once a year. With his personal efforts, backed by the cooperative's operations that delivered consistent quality and volume, Joaquim developed a diversified portfolio of buyers in Europe, the United States, and Japan.

Cooxupé is located in Southern Minas, a region that produces coffee beans with specific quality attributes. With regional growth, Cooxupé started to originate coffee beans from Cerrado Mineiro and Mogiana, with different and complementary coffee attributes. Regional diversification was considered a necessary strategy to sustain the direct export program as importers and roasters like to blend coffees from different regions and quality attributes. The success of Cooxupé's export program is shown in figure 3, which shows significant growth in coffee bags received and direct coffee exports since the early1980s.

Cooxupé in 2006

As a result of export-growth, Cooxupé became the largest coffee marketing and exporting cooperative in the world. In 2005 it generated sales of R$1,191 million, which is about USD 500 million. Its total assets reached R$862 million with net equity of R$190 million (table 1). It received 2.5 million bags of coffee in 2005—equivalent to 11% of total Brazilian production—from 10,616 members in 171 counties located in three main regions (table 2). The largest 20% of members deliver 80% of the coffee marketed by the cooperative.

| 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sales | 466.39 | 530.24 | 635.34 | 934.58 | 1,190.57 |

| Net income | 12.01 | 16.00 | 18.54 | 21.09 | 30.08 |

| Current assets | 279.42 | 405.67 | 436.75 | 578.36 | 710.49 |

| Fixed assets | 36.58 | 39.24 | 44.66 | 89.69 | 93.78 |

| Total assets | 321.43 | 516.29 | 567.41 | 713.94 | 861.86 |

| Current liabilities | 154.01 | 223.80 | 235.74 | 445.18 | 519.13 |

| Long-term liabilities | 77.07 | 188.18 | 214.41 | 98.10 | 153.15 |

| Owners' equity | 90.34 | 104.30 | 117.25 | 170.64 | 189.57 |

| Social capital | 45.90 | 54.77 | 61.84 | 71.97 | 85.20 |

- Source: Cooxupé's annual financial reports.

| Region | Counties | Members |

|---|---|---|

| Southern Minas | 70 | 7,989 |

| Cerrado Mineiro | 44 | 721 |

| Mogiana | 30 | 573 |

| Other | 27 | 1,333 |

| Total | 171 | 10,616 |

- Source: Cooxupé's annual reports.

Technical Assistance

Cooxupé provides free technical assistance to members. On one hand, this policy might be considered a problem because most members do not value a free service. In addition, it represents an additional cost to the cooperative that competitors (private exporters) do not incur. However, the cooperative has historically provided technical assistance to members. Technical development is considered a “trust business” as the agronomists develop close relationships with members. A valuable communication channel is thus established with the membership. The service is funded from retained surplus in a special equity reserve account known as FATES (Fundo de Assistência Técnica, Educacional e Social).

Cooxupé's technical development team is composed of thirty-two agronomists. Given the relative small size of the technical development team, Cooxupé does not provide personalized technical assistance to members. Most of the technical development efforts are conducted in group meetings and technical demonstrations on experimental fields. Best agronomic practices are shown in several field days during the year. The technical development team also provides internal services and information gathering that are used by other business units, including crop forecasts and technical analysis for credit purposes.

Coffee Grading

Coffee grading is central to Cooxupé's strategy of adding value to members' coffee. Without a coffee grading system developed for Southern Minas coffees, Cooxupé would not have been successful in developing direct supply relationships with coffee buyers in major import markets. Over the years, Cooxupé has developed a complex grading system with sixteen grades based on eight attributes (crop year, visual aspect, humidity, quantity of defects, impurity, flavor/drink, body, and aroma). The sixteen basic grades are broken down into specific quality variations serving two purposes: (1) to determine the price to be paid to the member; and (2) to offer buyers a broad variety of consistent coffee grades every year.

Coffee grading at Cooxupé is conducted by a team of four-quality experts (graders) with the assistance of four trainees. The final grade assigned to a coffee sample by a grader must be approved by two other graders. In other words, at least three of the four graders must agree on the final grade assigned to each sample. These four graders have been working together at Cooxupé for more than twenty years. The grading process is organized in three stages at Cooxupé. The first stage—known as preclassification—occurs when the truck with a load of coffee bags arrives at a Cooxupé warehouse. At this stage, about 30% of all coffee bags are sampled and the grader determines a “pregrade” based on visual inspection and aroma. This “pregrade” will determine the location on the warehouse where the truck is to be unloaded and the coffee bags to be stored in piles.

The second stage is coffee reception. Upon unloading from the truck, each coffee bag is sampled and an identification card is issued with the grower's information, number of bags, and the exact location of the coffee bags in the warehouse. Each sample, along with the identification card, is sent to the grading department where it will be assigned a grade based on the eight attributes mentioned above. The third stage is the final grading of each coffee sample. The team of graders must issue a final grade to each sample within twenty-four hours. After the grading process is finalized, a warehouse receipt is issued to the member with grades for each coffee sample. When the member wants to put a sell order, he/she does so in the marketing department and the coffee price is based on the grade found in the warehouse receipt. All samples are stored in the cooperative until the member puts a sell order.

Coffee Pricing

Coffee is a crop with pronounced price variability. Perhaps not surprisingly, Cooxupé increasingly uses financial derivatives to hedge against price risk. Over the last ten years, the average coffee price received by Cooxupé producers was USD 90 per bag, with the highest average price of USD 181 in 1997 and the lowest of USD 39 in 2002. According to Cooxupé's analysis, coffee production costs in Southern Minas total R$312 per bag for a producer with average productivity (around 20 coffee bags per hectare). Production costs are lower (R$273 per bag) for high-productivity (30 bags/ha) growers and as high as R$575 per bag for low-productivity growers (10 bags/ha). In addition to world coffee prices (quoted in USD), the exchange rate and productivity are the major determinants of a producer's net income.

Financial Management

Cooxupé's social equity capital is divided in quotas valued at R$1.00, which are nontransferable and thus nonappreciable. There is no upper limit to the amount of quotas an individual member may hold, but each member must invest in quotas proportionally to farm size. The minimum equity investment is R$550 per member. In addition to this minimum amount, members must invest R$100 per hectare planted with coffee; R$10 per hectare used in crop or animal production; and R$24 per hectare used in other activities. Social capital is redeemable when the member leaves the cooperative. It is the board's decision when and how to retire members' equities, but the cooperative bylaws state that the total equity capital of a retired member must be redeemed in monthly installments not exceeding 36 months.

Cooxupé allocates net savings to the legal reserve fund and FATES accounts as mandated by the national cooperative law. Any net savings above these legal requirements are also retained as cooperative equity capital. Thus, Cooxupé does not pay patronage dividends despite the fact that the bylaws allow for patronage dividends up to 12% of a member's equity investment. In 2005 Cooxupé had R$189 million in total equity capital, equivalent to 22% of total assets. During the previous five years, equity capital more than doubled, up from R$90 million in 2001. Social capital—that is, equity capital in the form of quotas—was valued at R$85 million (or 45% of total equity) in 2005, while the remainder was unallocated capital in various reserve accounts (table 1).

Challenges for the Future

Sipping a freshly brewed cup of coffee, Joaquim felt good to be back at home. He was proud of the fact that over the years Cooxupé was able to build a strong presence in the world coffee industry. Total export volume reached 1.4 million bags in 2005, positioning the cooperative among the top-five coffee exporters in Brazil. Perhaps more importantly, Cooxupé had developed a valuable intangible asset in the market as its brand name was recognized by major buyers as synonymous with quality and consistency. It had reputation and enjoyed “open doors” in international markets.

Yet Joaquim felt that Cooxupé had many challenges to address. The main challenge ahead was to keep growing with consistency. Increasing the volume of coffee sales in both export and domestic markets was essential to operating in a highly volatile, decreasing margin commodity business. In other words, the cooperative needed to grow to remain viable but this growth had to occur without jeopardizing the cooperative's tradition as a high-quality and consistent coffee exporter. Additionally, growth strategies should also contribute to the cooperative goal of increasing members' incomes. He wondered what strategies the cooperative should pursue to provide income growth opportunities to its members and to build on its reputation in the marketplace.

Another challenge was to continue to earn members' trust. Cooxupé's principle of “full liquidity” was very important to members. The cooperative warehouse was the “member's bank” where members deposited their savings. As such, the cooperative had to provide liquidity every day. But this strategy created a heavy burden on the cooperative balance sheet as it required increasing amounts of working capital. To finance its working capital needs, the cooperative had access to low-cost sources of short-term funds, including export credits (known as ACCs) and funds from the national rural credit system. On the other hand, the “full liquidity” strategy, coupled with other efforts (technical assistance, the country store, and short-term credit provision), were instrumental in developing a close relationship with coffee producers. Originating high-quality coffees from different regions with low transaction costs was a core competence and a source of competitive advantage in the marketplace.

Finally, Cooxupé has grown over the years with the same, traditional organizational structure. If the cooperative continues to expand and adopts new strategies to cope with an increasingly complex, unstable and competitive environment, Joaquim wondered whether the traditional cooperative structure should be adapted to these new internal and external contingencies. More specifically, how could the cooperative ownership structure be changed to provide the business with additional sources of risk capital?

Acknowledgments

This teaching case study was developed from primary data collected directly from Cooxupé. It is intended to be used in competitive strategy and agribusiness management courses. A teaching note is available upon request from the authors ([email protected]). The authors would like to thank Cooxupé's leaders, especially Joaquim Libânio Ferreira Leite, for providing the information and support necessary for this case development.