Assessing the Effect of Bilateral Collaborations on Learning Outcomes

Abstract

Despite recent interest in the effects of student-driven collaborations on learning outcomes, little or no empirical investigations examine the potential benefits from collaboration between instructors of separate, but related, courses. This study proposes a learning intervention that explicitly accounts for interdependencies across courses and extends the traditional definition of collaborative learning to include the synthesis of teaching and learning in four courses through bilateral, group activities between instructors and among students. A student-performance measure assesses the intervention. Statistical results suggest that the collaborative learning intervention improved student-writing performance.

Although the traditional lecture format remains the primary mode of instruction in most economics courses, interest in alternative instructional methods is increasing. Pedagogical literature and experts tout the benefits of active and collaborative learning, yet only a few studies assess the quantitative impact of these techniques on student learning. Active and collaborative learning has been shown to enhance learning by stimulating stronger interest in the subject matter and promoting critical thinking skills (Totten et al.; Siegfried et al.; Wilson). Active learning usually emphasizes student participation through activities that involve collaborations among students in discussions and problem solving. Students at various performance levels collaborate to achieve a common learning objective by working on exercises or conceptual experiments in small groups within and outside the classroom setting. The small group interactions are usually problem-based and are intended to encourage critical thinking. The collaborative learning activities may culminate in written reports and oral presentations and are believed to increase the quality of these learning outputs. Several authors have identified a significant link between clear writing and critical thinking (Bean; Hansen; McCloskey).

Several studies have investigated the effectiveness of alternative instructional methods. For example, Jensen and Owen investigated the contribution of various teaching techniques to student learning and performance and concluded that it is more effective to devote more class time to active learning involving discussions and interactions among students. In a recent analysis of the impact of collaborative problem solving in economics, Johnston et al. found limited empirical support for the positive effects of collaborative problem solving on exam grades. In another study, Wilson examined the impact of team-based decision making relative to individual decision making on learning outcomes in a fourth-year and graduate-level managerial finance course over 1985–2002, finding that the team-based approach to problem solving has a significantly positive effect on learning outcomes. Stephenson et al. (2005) and Batte, Forster, and Larson assessed student performance in distance courses. Stephenson et al. (2001) found a modest impact on student performance from a web-based instructional tool.

In contrast to recent interest in the effects of student-driven collaborations on learning outcomes, to our knowledge no previous empirical investigations have examined the potential benefits from collaboration between instructors of separate but related courses. Most academic departments offer a variety of courses that form an integrated whole in the course offerings available to students in various academic fields and majors. For example, students with majors in fields such as international trade or natural resource policy are required to take many of the same courses. Interestingly, several of the courses required for the majors usually have overlapping content and topical coverage. It is often assumed that the students will discover the linkages across these courses on their own. We argue in this study that learning interventions that explicitly account for interdependencies across classes via collaborations between instructors and among students have the potential for enhancing student learning outcomes and helping to achieve important learning objectives such as the development of skills that engenders critical thinking, clear economical writing, clear argumentation, and competency in oral presentations.

Our paper fills an emerging niche in educational policy by focusing on several current challenges, including: the quantitative measurement of qualitative products, improving written communication, and improving learning outcomes. As shown in recent research, higher education is increasingly interested in documenting and improving learning outcomes—the “assessment process” (Becker and Watts; Devadoss and Foltz; Becker; McDaniel and Colarulli; Simkins; Yamarik). The quality of student writing, however, is difficult to quantify and therefore it is challenging to document improvements. This study offers a strategy to evaluate student writing quantitatively, and it offers strong evidence that the intervention described here substantively improves student-learning outcomes. These improvements are available without changing the preparation of the students or their abilities, i.e., changing the student body.

In this paper, we propose a teaching intervention that more explicitly captures the interdependencies of courses across major areas within an academic department. This study extends the traditional definition of collaborative learning to include the synthesis of teaching and learning in two pairs of separate, but related, courses through bilateral, group activities between instructors and among students. Collaborations in teaching by instructors could involve joint planning and designing of curriculum contents with particular emphasis on linkages between both courses. In addition, students could collaborate on a similar topic (e.g., analyzing trade and environmental policy), which motivates critical thinking, enhances group discussions, and serves as a basis for written and oral communication activities. Specifically, students collaborate as members of small groups in discussions and writing exercises that resulted in graded “policy briefs” and oral presentations at a jointly organized bilateral colloquium for both classes.

A regression analysis isolates the benefits of the intervention from other drivers of student performance. The results show that the intervention has a statistically and substantively significant impact on learning outcomes—averaging more than one point of increased performance on a ten-point scale. This benefit measure is the principal result of the paper; however, we acknowledge that there is no companion quantitative measure of costs. It is unknown whether the intervention has net benefits. We have found, however, that costs mainly accrue to faculty and they include a loss of individual faculty autonomy, increased effort, and potential conflicts among faculty (McDaniel and Colarulli). Since benefits mainly accrue to students and costs accrue to faculty, the intervention will likely not constitute a Pareto improvement unless faculty members specifically desire or administrators reward faculty for an improvement in student performance.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. The second section provides a description of the bilateral collaborative learning exercise and the assessment plan. The third section describes the data collected and basic hypotheses. The fourth section presents the results of several empirical models, finding a statistically and substantively significant impact of the learning intervention. The final section concludes by focusing on the impact of the results on pedagogy, learning outcomes assessment, and educational policy.

The Learning Intervention: Bilateral, Collaborative Design

The bilateral collaborative learning exercise has multiple rationale and goals. The collaboration between instructors and among students ought to better highlight the interdependencies in the conceptual issues covered in each of the courses. The instructors for both courses collaborated in the planning and development of specific topical issues driving the learning intervention and the colloquium. In addition, the syllabi for the separate courses were revised and coordinated to reflect and emphasize the collaborative course format. In a more general sense, the bilateral and collaborative learning interventions ought to enhance students' critical thinking abilities as they develop higher competence levels in their writing and oral presentation skills (Hansen; McCloskey). A more specific objective of the intervention (as implemented by the authors) is to bridge the gap between students' knowledge of developed nations' agricultural and trade policies and their economic and environmental impacts in the developing world.

Learning Outcomes Assessment

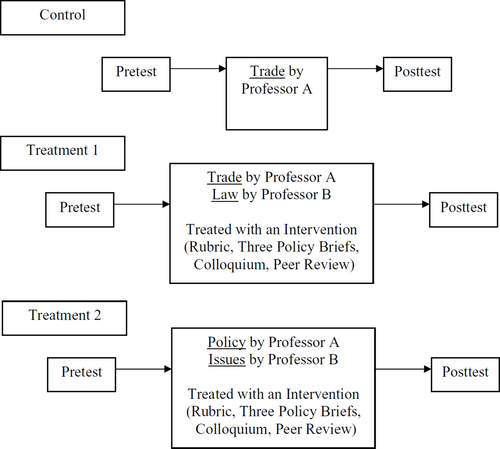

The impact of two sets of pedagogical interventions on student learning is assessed in four separate “treatment” courses and one “control” course taught by the authors (see conceptual model in Figure 1). The change in the quality of student writing between pretests and posttests is analyzed statistically, controlling for the learning-intervention treatment. In the rubric used to guide and evaluate student writing, quality includes both content and style components. However, evaluative criteria focusing on content and argumentation receive much more attention than style.

The writing takes the form of “policy briefs,” which emphasize the development of logical thinking and writing clarity. Both control and treatment groups produce pretest policy briefs, but only the treatment group is exposed to the learning intervention prior to producing the posttest policy brief. The intervention has five parts: (a) a colloquium; (b) three intermediate policy briefs; (c) collaborative activities/exercises; (d) peer review; and (e) application of a writing rubric.

Diagram of intervention and assessment plan

Policy Briefs

Assessment of student learning relies entirely on the pretest and posttest policy brief, and so it is necessary to describe in some detail the structure of this form of written communication. A policy brief is simply a short (one page) writing assignment that begins directly with a thesis on an important economic question and then makes two main points to support that thesis. In a given semester, pretests and posttests in both classes address the same policy brief issue (PBI). Two issues were used in this study.

- PBI-1: Make an argument about how increasing free trade affects environmental policy and practices in the developed world and the poor in developing countries.

- PBI-2: Make an argument about how agricultural policy in the developed world affects the poor in developing countries.

The treatment group also produced three graded policy briefs on related questions during the course of the semester (see below for details). In addition to developing the policy brief questions, the instructors also developed an evaluation rubric for guidance to students in their written work and oral presentations. This rubric defined quality in terms of policy persuasion, academic excellence, correct application of course concepts, and clarity of written communication. These forms of writing helped students build and refine their analytical argument through peer review, and had a goal of breaking the overall problem into less intimidating steps. In addition, students in small groups of four or five members present their fifth policy brief at the colloquium.

The Colloquium

From the students' perspectives, the defining characteristic of the intervention is the joint seminar/colloquium. In the colloquium, two treated courses come together for three hours near the end of a semester to make oral presentations on and discuss the same PBI. The colloquium itself emphasizes the development of oral argumentation and presentation skills; it also creates an incentive to produce quality work using a peer evaluation, which all participants complete. The colloquium also provides opportunities to evaluate oral communication styles and to compare analytical results in one class to those in another (i.e., exploring different approaches to knowledge in subfields of economics, policy, and law).

Presentations are made in small groups, but each member is required to participate. After each presentation, the students in the audience and other participants are allowed to ask probing questions, make evaluative statements, or identify logically inconsistent claims in the presented arguments. The instructors serve as moderators for the colloquium.

The Courses

The teaching interventions were applied in two phases over two consecutive semesters to two sets of courses. All four courses were primarily developed for student majors (from natural resources management, resource economics, and food and agribusiness management), but all serve many other nonmajors.1Table 1 contains a summary description of the four courses and nature of the teaching interventions. In the first phase of the project, the teaching interventions were applied to the following set of courses: Issues in Natural Resources and the Environment (“Issues”) and Agricultural and Natural Resource Policy (“Policy”). Both of these courses were offered in the spring 2005 semester. Although the “Issues” course is a nontechnical treatment of issues in natural resource and the environment, the course content has some overlap with “Policy,” which emphasizes the application of various analytical tools in its treatment of agricultural and natural resource policies. The “Policy” course assumed prior exposure to graphical analysis of economic concepts while the “Issues” course did not. Thus, the bilateral collaborations among instructors and students across these two courses allow for the comparison of both conceptual and technical analysis of agricultural and natural resource/environmental economic issues.

| Course #1: Environ. Issues | Course #2: Ag. Policy | Course #3: Ag. Trade | Course #4: Environ. Law | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semester | Spring 2005 | Spring 2005 | Fall 2005 | Fall 2005 |

| Description | Nontechnical introduction to various issues in natural resource and environmental policy. Assumes no prior exposure to economic concepts | Emphasizes the application of various analytical tools in its treatment of ag. and natural resource policies. Assumes prior exposure to graphical analysis of economic concepts | Focus on linkages in the global economy and emphasizes the implications of the U.S. government policies for ag. trade relations with other countries | Emphasizes the U.S. domestic environmental laws and policies |

| Credit-Hours | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Required/Elective | Elective | Group requirement/Elective | Group requirement/Elective | Group requirement/Elective |

| Classification | All years | 3rd/4th | 3rd/4th | 3rd/4th |

| Focus of Collaborative Intervention | Impact of developed nation ag. policy in developing nations | Impact of govt. policies in the U.S. and other developed nations | Impact of environmental policies on global trade volume | Impact of trade policies on the environment |

The second phase of the exercise was implemented during the fall 2005 semester and it involved this set of courses: International Agricultural Trade and Marketing (“Trade”) and Topics in Environmental Law (“Law”). While the “Law” course emphasizes domestic environmental laws and policies, the “Trade” course introduces students to the global economy and emphasizes the significance and implications of the U.S. government policies for agricultural trade relations with other countries. Although both courses seem very different, they address a surprising number of common issues. Nevertheless, the linkages between these two courses may not be as obvious, especially to students. In an increasingly global economy, it is critical that students learn to identify the interconnections and linkages between the U.S. environmental laws, global environmental outcomes, and the implications for international trade.

For each of the two phases, the students engaged in bilateral, group-based investigations of a common topic, centering on PBI. For PBI-1, students in the “Issues” course focused on measuring the impact of the U.S. agricultural policies on the developing world and students in the “Policy” course focused on understanding the various government policies in the developed countries and their economic implications for domestic agricultural markets. Intermediate policy briefs provided opportunities to refine arguments prior to the colloquium and the posttest, but also are a bit more course-specific as they emphasize the unique areas of emphasis that distinguishes the two courses. Several of these policy briefs required original social science research using secondary data sources. The intermediate policy briefs used in the first phase are as follows.

Issues

- Identify and evaluate measures of development (for the developing world) that are impacted by policy in the developing world. What outstanding issues of fact prevent development of superior measures? What outstanding issues of value exist and describe the substantive importance of these issues?

- Identify and develop an in-depth evaluation of the fairness of the global impact of one agricultural or natural resource policy in the developed world (i.e., what do winners win and losers lose)?

- Develop an in-depth policy assessment of how the policy identified in policy brief #2 could be changed to offer greater benefits to the poor in the developing world.

Policy

- Identify analytical tools for analyzing and measuring the economic impacts of alternative policy measures. Identify and evaluate key issues in developed country policy that affect developing countries. Distinguish between normative and positive economic issues.

- Identify specific U.S. agricultural and natural resource policies and evaluate how they affect domestic stakeholders and the poor in the developing world.

- Develop an in-depth policy assessment of how the policy identified in policy brief #2 could be changed to offer greater benefits to domestic stakeholders.

Similar to the first phase described above, the second phase courses had a common topic (PBI-2) in the area of free trade and the environment. The main tasks for students in the “Trade” course involved the understanding of how international trade policy can affect the environment in the developed and developing countries. In contrast, students in the “Law” course focused on identifying and analyzing specific U.S. environmental policies that has measurable impact on the volume of global trade in agricultural products. Students in the “Law” course did not complete intermediate policy briefs because the course had an additional requirement to complete a term paper on legal institutions affecting the environment. Nevertheless, this term paper involved group work and peer review. The intermediate policy brief questions for the “Trade” course are provided here.

Trade

- Identify a specific U.S. agricultural trade policy and evaluate how it affects an aspect of environmental quality, policy, and practices in the United States and in a developing country.

- Make specific arguments for how the policies in the United States identified above could be changed to offer greater benefits to domestic stakeholders.

- Identify analytical tools for analyzing and measuring the economic impacts of alternative free trade policy measures.

The control class was taught in the fall semester of 2004 with the same “Trade” class, which was later part of the treatment. Students in this class did not complete projects associated with the intervention, such as intermediate policy briefs, colloquium, or extensive peer review activities on PBI-2. However, these students did complete a pretest and posttest on the issue, PBI-2. Therefore, data from this class controls for the normal improvements in learning that occur over the course of a semester and manifest as a posttest that differs in quality from a pretest.

Overall, these learning interventions should help the students to understand how conceptual perspectives and points of view affect the ways one answers policy questions. Furthermore, it is expected that, in addition to the oral presentations at the colloquium, the opportunities for students to work in groups to discuss course content issues and solve problems would result in the development of effective skills in oral and written communication, quantitative reasoning, and the use of information technology.

Data Collection for Learning Assessment and Variables

Data were collected in the form of pretest and posttest policy briefs from 84 students in three semesters. A dichotomous variable, INTERVENTION, is used to indicate the 83% of students in the treatment group. The study uses an objective measure of student performance. An economics professor from a different institution, with experience in these topic areas, provided scores on anonymous versions of 168 pretests and posttests, i.e., two writing samples per student. The rubric guiding the student writing assignments was used to guide this assessment. To reach agreement with the outside professor on what the rubric terminology means, we conducted a “norming” exercise by scoring 10 illustrative policy briefs (which are not in the final sample) and explaining on the rubric why each policy brief was scored as it was. The outside professor assigned scores without knowing that some assignments were pretests and others were posttests or that there were two assignments from each student. Scores (PRESCORE, POSTSCORE) were assigned using an integer scale ranging from –5 to 5 where three qualitative designations enhanced the quantitative score. Positive (negative) scores represented above-average (below-average) performance. A zero score indicated average performance.

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics. Average POSTSCORE exceeded PRESCORE (1.24 versus 0.36), which suggests that participating in the class tended to improve performance regardless of the intervention. The external grader did an excellent job of following the rubric closely. All scores but –5 were assigned, and the mode and median were zero, i.e., an average policy brief. The numerical average grade of 0.80 is close to the rubric's average score of zero.

| Variables | Description | Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| POSTSCORE | Dependent variable: Score issued by external grader on posttest writing assignment (integers–4 to 5) where negative numbers represent below average writing, zero indicates average writing, and positive represents above average writing | 1.24 (2.76) | –4,5 |

| PRESCORE | Score issued by external grader on pretest writing assignment (integers –4 to 5) where negative numbers represent below average writing, zero indicates average writing, and positive represents above average writing | 0.36 (2.54) | –4,5 |

| CHANGE | Dependent variable: POSTSCORE–PRESCORE | 0.87 (2.69) | –6,8 |

| INTERVENTION | Indicator: Policy brief from class treated with the intervention (omitted default is no intervention) | 0.83 (0.37) | 0,1 |

| YEAR3rd | Indicator: Classified by credit hours as a third-year student at beginning of semester (omitted default is first- or second-year student) | 0.26 (0.44) | 0,1 |

| YEAR4th | Indicator: Classified by credit hours as a fourth-year student at beginning of semester (omitted default is first- or second-year student) | 0.63 (0.49) | 0,1 |

| GPA | Student's GPA at beginning of semester | 2.85 (0.62) | 1.20,3.87 |

| MAJOR | Indicator: Student who took more than one of the classes in the study—typically, students in the major for which these classes are required (omitted default are students taking only one class in study) | 0.21 (0.41) | 0,1 |

- Note: N = 84.

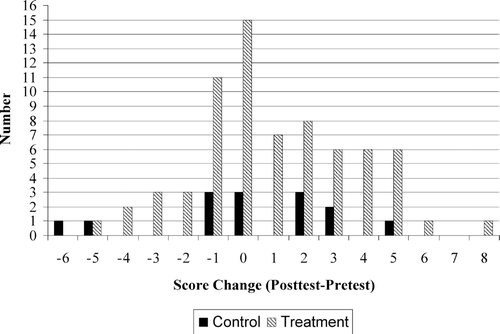

The dependent variable measuring student performance is the change in score between the pretest and posttest: CHANGE = POSTSCORE–PRESCORE. The mean of CHANGE is 0.87 indicating that students tended to improve slightly over the course of the semester, though it should be recognized that this mean value is highly sensitive to large changes by individual students. Figure 2 presents a histogram of all observations of CHANGE, i.e., changing from PRESCORE = –2 to POSTSCORE = 4. The figure shows, somewhat surprisingly, that some student performance declines over the semester, and the low mean value of CHANGE suggests that average student improvement is small. One can hypothesize many reasons for these counter-intuitive results. For instance, students are more eager to please professors, or work harder, at the beginning of the semester. Or, students have greater certainty about course grades at the end of the semester, and some may not put in effort if it is unlikely to change their course grade. Although this study offers several controls to test for drivers of CHANGE, the focus of the analysis is on the impact of the intervention and not on trends in student performance over a semester. The regression approach controls for multiple drivers simultaneously and thus is superior to a simple difference of means test.

The control and treatment distributions of CHANGE can also be compared using descriptive statistics, which inform the impact of the intervention across the entire class rather than simply focus on the mean impact. The assumption of normality cannot be rejected for either distribution. Accordingly, it is appropriate to apply an equality of variances test, following the F-distribution. No evidence is found to suggest unequal variances. Finally, although the skewness measures have slightly different point estimates (−0.61 for the control group and 0.18 for the treatment), the kurtosis measures are similar (2.70 for the control group and 2.71 for the treatment group). Hence, there is no strong statistical evidence that the distributions are different in higher moments, and the ensuing analysis of the mean likely reflects most of the impact of the intervention.

Histogram of score changes by intervention (N = 84)

The variable CHANGE is a measure of performance that differs from many other studies, which focus on a single, final measure of performance, like a test (Stephenson et al. 2005), final grade (Stephenson et al. 2001), or a percentile rank in a course (Batte, Forster, and Larson). Although no perfect measure of performance is available (Stephenson et al. 2005) and it is difficult to attribute all changes in performance to the intervention, we offer an analysis of this measure as one possible measure of the change in performance due to the intervention. A model will be tested that explains this change with student-characteristic data.

Three variables measure student-specific characteristics. GPA measures a student's grade-point average at the beginning of the semester in which the data are collected. Following other studies' results (Stephenson et al. 2001; Stephenson et al. 2005), we hypothesize that students with higher GPA should tend to have higher POSTSCORE. That said, students with high GPAs should also have higher PRESCORE (correlation = 0.49), so it is not obvious that CHANGE should increase with GPA.

Student year offers another possible control variable in explaining change in performance. YEAR3rd and YEAR4th indicate third- and fourth-year students, respectively. Most of the sample includes these advanced students. As with GPA, student experience is expected to affect performance on pretests and posttests, but there are no obvious hypotheses available for how experience will affect the change in performance.

Some students took more than one of the four courses from which data are collected. These students tend to be from majors that specialize in and emphasize the course material in the four different courses in the study, and these students should have higher interest in and experience with the coursework. MAJOR indicates the students who took two or more courses from the four offered in the study. One anticipates that students in the major will perform better (as found in Batte, Forster, and Larson), but it is not clear how this variable affects CHANGE. Of the observations, 21% were produced from students taking two or more courses, and three students in the control group subsequently took a treated course. It should be noted that the use of multiple observations from the same students likely introduces some systematic component to the error term in a regression, and MAJOR is likely inadequate to control for this. Hence, the conclusions will not draw solely on the regression results.

Results

The data suggest that participation in the course is correlated with improved writing quality. The average pretest score was 0.36, while the average posttest score was 1.24 see (Table 2). For the control group, 43% of students improved their writing quality between the pretest and posttest, while 36% declined. In the treatment group, 50% improved and 29% declined.

There is also evidence that suggests the intervention is correlated with improved quality. The correlation of CHANGE and INTERVENTION is 0.11. Note that 21% of students in both groups had no change in writing performance. Consider that the ratio of improvements to declining writing is greater in the treatment group (1.72) than the control group (1.19). Finally, the increases in performance of the treatment group tended to be of a larger magnitude than the control group, while the decreases tended to be of a lower magnitude.

It is difficult to examine the CHANGE variable and make firm conclusions about what drives changes in student performance. There can be many reasons apart from course learning why scores change between pretest and posttests. For instance, some students may be more concerned with excellent performance at the start of a semester, when much of their grades are uncertain, than at the end of semester when final grades are all but determined. Reasons such as this explain why some students' performance may fall between these two writing assignments and yet these reasons are immaterial for the regression results since they affect treatment and control groups similarly.

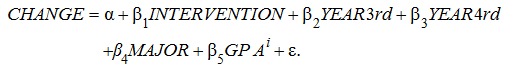

(1)

(1) (2)

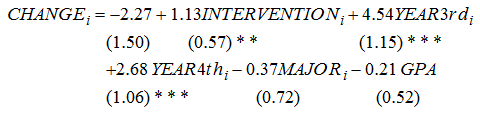

(2)The results suggest that the intervention (INTERVENTION) has a significant and positive effect on performance. This reinforces the principal result of the paper—that the intervention increases performance. The coefficient estimate suggests that, on average, the intervention increases performance by over one point (1.13) on the −5 to 5 scale. This point-estimate improvement exceeds the average improvement associated with the pretest and posttest of 0.87, i.e., the effect of learning in the class.

Variables controlling for student year are also found to be significant. Relative to first- and second-year students, third- and fourth-year students perform better. These effects are large. Although not the focus of the paper, several explanations for these effects are possible. More advanced students may be more focused on grades, more talented at writing, or more experienced with the course content. Reasons that third-year students tend to outperform fourth-year students may involve the focus of third-year students on applying for jobs and graduate school in the near future, while fourth-year students may already have positions lined up following graduation. In one instance of the intervention, the classes were taught in the spring and so the final writing assignment was due very close to graduation and fourth-year students may have been suffering from “senioritis.” Finally, it is possible that there was a cohort effect.

Summary and Concluding Remarks

This paper describes a unique learning intervention, which links separate courses and which seeks to enhance student critical thinking and writing performance. To our knowledge, no previous study has conducted an empirical analysis of the impact of teaching collaborations among faculty members in the economics profession. In this study, we offer the first analysis of the potential gains from such bilateral collaborations among faculty members who teach courses with overlapping or complementary contents. Data were collected to measure quantitatively the change in writing performance associated with the intervention. Descriptive statistics and regression results suggest several conclusions. First, improvements in performance appear correlated with class learning and the intervention. Second, regression results suggest student-learning performance improves because of the intervention. Third, the improvement in student learning outcomes is of substantive significance—over one point on an eleven-point scale—and may be larger than the increase in performance associated with participating in the class itself. The improvement from the intervention is of a magnitude such that it may counteract a lack of preparation by some students. Of course, the intervention need not substitute for preparation and ability and can augment these factors.

Fourth, the results on the relative importance of the intervention are important for educational policy since they offer statistical evidence that suggests how faculty can improve student-learning outcomes. A student's preparation (PRESCORE) and abilities (GPA) are not choice variables, but the learning treatment (INTERVENTION) is. As measuring student learning outcomes and achieving ever-higher learning goals increases in importance, faculty and administrators will be looking for improvement strategies. This intervention improved outcomes slightly, and the instructors perceive the additional costs of the intervention to be relatively small. Other instructors may want to explore this approach and may find different observed benefits and costs.

Fifth, the analysis of the intervention demonstrates that assessing learning outcomes can be quantitatively rigorous even when the product of student learning is writing. Qualitative evaluation of student writing can be expensive and some may charge that the evaluation process is ad hoc or that it cannot be replicated easily. This study bridges the divide between qualitative and quantitative analysis when the quality of writing is evaluated. Further, it suggests a low-cost assessment strategy for other faculty to analyze quantitatively what many consider strictly qualitative outcomes.

Finally, while we have demonstrated bilateral collaborations between instructors could be beneficial to students' learning outcomes, there are also potential costs to faculty members. Some of the costs of faculty collaborations include: (a) the loss of complete individual faculty autonomy over course content and syllabus; (b) extra time required for coordinated preparation and planning for the joint segments of the two courses; and (c) potential for personal conflicts between colleagues (McDaniel and Colarulli). Nevertheless, the costs of collaboration may not be prohibitive if the two courses are truly overlapping and the collaborating colleagues are committed to working together and making a few compromises. Furthermore, if the courses under consideration are offered frequently (e.g., biannually or annually), then the marginal cost of various segments of the collaboration may diminish over time while the long-term benefits may increase with more experience with the format. We encourage further investigations of the impact of this teaching and learning approach by others in the profession.

Acknowledgments

The authors owe debts of gratitude to Steve Bernhardt, Dee Baer, and Dorry Ross, for providing valuable feedback as this learning intervention was designed and implemented and to Scott Steele for his help in evaluation. Gabriele Bauer, Martha Carothers, and Tom Ilvento also provided valuable guidance and arranged support for this project. This project was funded by a grant from the University of Delaware's Center for Teaching Effectiveness, General Education Initiative, and Information Technology.