U.S. Foreign Direct Investment in Food Processing Industries of Latin American Countries: A Dynamic Approach†

This paper was prepared for presentation at the Principal Paper session, “Outsourcing and Foreign Direct Investment: Boon or Bane?” Allied Social Sciences Association annual meeting, Philadelphia, January 7–9, 2005.

The articles in these sessions are not subject to the journal's standard refereeing process.

The purpose of this paper is to examine the determinants of U.S. foreign direct investment (FDI) in the food processing industries of Latin American countries using a dynamic investment model. While past literature has addressed U.S. FDI in food processing to a great extent, most of the studies focused on U.S. food processing investment in developed countries (e.g., Gopinath, Pick, and Vasavada; Marchant, Cornell, and Koo); mainly because they were destinations for the majority of U.S. investment capital.

Studying U.S. investment in Latin America's food processing industries is important in light of the Free Trade Area of Americas (FTAA) under negotiation. It is expected that the FTAA will significantly reduce trade and investment barriers between the Western hemisphere countries and likely affect their economic conditions (e.g., wages, FDI receptiveness, taxes, exchange rates, etc.). Changes in the economic conditions could influence foreign investment decisions by U.S. multinationals.

Studies that address FDI in food processing have used a static framework to model the investment process. However, the assumption that capital investment is independent across time may not accurately represent reality. Approaching investment modeling from a dynamic perspective is more realistic. In addition, it is important to calculate short- and long-run effects of changes in selected exogenous variables on the U.S. FDI position in food processing industries in Latin America.

Dynamic models have been widely used to study investments and the capital adjustment process (Chirinko; Pindyck and Rotemberg; Shapiro; Morrison). These studies found that the adjustment costs of investment mandate the use of dynamics in modeling firms' decision processes. Firms tend to spread their investment activities over time because it may become costly to achieve an investment position target within a relatively short period of time. Thus, adjustment costs are important in foreign investment decisions because the larger the amount of investment, the more costly it becomes to adopt investment capital, and a certain portion of those costs may grow at an increasing rate.

Model

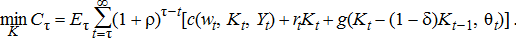

(1)

(1)The first two terms (c(·) and rtKt) represent a standard, one-period cost function. The first term, c(·), depends on the real price of foreign labor (wt), foreign direct investment stock (Kt), and final output (Yt). The last term, g(·), is an adjustment cost function that represents costs of adjusting foreign capital stock through investment. θt stands for various country-specific factors that may influence the cost of adjustment. ρ is a discount factor, δ is a depreciation rate, and rt is the real price of capital. Eτ is an expectation operator.

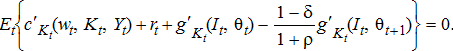

(2)

(2)The Euler equation (equation (2)) represents a rule of optimal allocation of foreign investment capital over time, stating that the marginal cost of investing an additional unit of capital at time t must equal the discounted marginal adjustment cost at time t + 1.

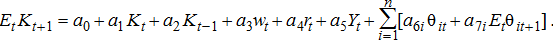

(3)

(3) (4)

(4)In equation (4), λ1 and λ2 represent roots of the Euler equation. For a converging solution, one of them needs to be between zero and unity and another one must be greater than unity. The magnitude of the root is an indicator of the speed of foreign investment adjustment. The closer it is to one, the slower the adjustment process.

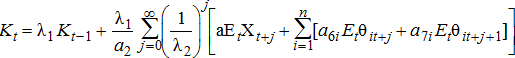

(5)

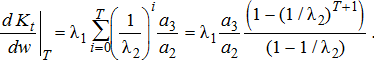

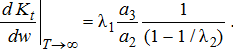

(5) (6)

(6)Derivation of the effects of shock in interest rates and sales are analogous to those in real wages.

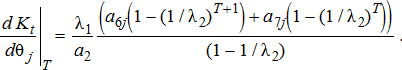

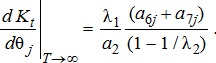

(7)

(7) (8)

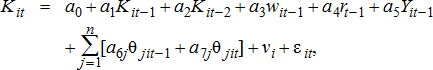

(8)Econometric Specification and Estimation Procedure

(9)

(9)Potential econometric problems in estimating equation (9) exist mainly because the data set is a panel and the Euler equation contains lagged dependent variables. Because of the nature of the panel data, the error term may contain a random effect (vi). In addition, the presence of lagged dependent variables as independent variables in equation (9) may cause a simultaneity problem. We used the Arellano-Bond GMM procedure designed to estimate linear models with lagged dependent variables using panel data (Arellano and Bond; Stata).

Data

The panel data range from 1983 to 2000. The countries included are Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Panama, Peru, and Venezuela. FDI position, wages, and sales of foreign affiliates were obtained from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Nominal exchange rates were taken from the Web site of the Economic Research Service, USDA, and Latin American consumer price indices were from the World Development Indicators published by the World Bank.

The cost of foreign investment capital was measured by U.S. real interest rates since U.S. multinationals finance the FDI. U.S. real interest rates were obtained from the World Development Indicators database. Country-specific factors that may influence adjustment of foreign capital stock, including market size, measured by real GDP; taxes on income, profits, and capital gains as a percentage of current revenue; nominal exchange rates; and the level of FDI in a country as a percentage of GDP were taken from the World Development Indicators database.

The data set used in estimations contains missed observations. Some data were missing because the data did not exist, or because they were not disclosed. This did not create a problem for our estimations since the Arellano-Bond General Method of Moments (GMM) procedure (Hansen) for dynamic panel data in STATA 8.0 is able to conduct estimations despite missing data in the middle of the panel.

Estimations and Results

Estimation of the Euler Equation

Table 1 presents the estimation results of equation (9). The estimated coefficients constitute the base for calculating the effects of changes in the expected values of the variables (wages, interest rates, and macro variables influencing adjustment of capital) on the FDI position in the food processing industry.

| Dependent variable - FDP, t | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Coefficients | Standard Errors |

| FDP, t−1 | 1.214 | 0.121*** |

| FDP, t−2 | −0.156 | 0.113 |

| Exchange rate, t | 0.864 | 2.701 |

| Exchange rate, t−1 | −1.556 | 2.969 |

| Tax, t | −0.135 | 0.066** |

| Tax, t−1 | 0.022 | 0.067 |

| GDP, t | 0.210 | 0.334 |

| GDP, t−1 | −0.124 | 0.385 |

| FDI openness, t | −0.049 | 0.152 |

| FDI openness, t−1 | −0.336 | 0.163** |

| Wage, t−1 | 2.272 | 0.596*** |

| Interest rate, t−1 | 0.392 | 0.295 |

| Sales, t−1 | −2.577 | 0.583*** |

| Constant | 0.563 | 0.289* |

- * Significant at 10%.

- ** Significant at 5%.

- *** Significant at 1%.

The estimated coefficient representing FDI positions lagged one year is statistically significant at 1%. This supports the hypothesis that capital investment decisions are likely to be interrelated across time, and modeling FDI in a food processing industry in a dynamic setting is appropriate.

Macro variables yield mixed results in the regression. Current nominal exchange rate and lagged exchange rate are not statistically significant. The variable measuring the level of taxes paid in Latin American countries in the current period is statistically significant at 5%. However, lagged tax level is not statistically significant. Real GDP, measuring the size of the market for U.S. food processing firms, is not statistically significant at current or lagged levels. The one-year lag for the general openness of Latin American countries to FDI (measured as a percentage of gross FDI in countries' GDP) is statistically significant at the 5% level. The real interest rate, representing the costs of FDI, is not statistically significant at conventional levels. Real wages and processed food sales are statistically significant at 1%.

The U.S. food processing multinationals do not seem to consider the host country's market size. Instead, the multinationals appear to target only specific groups of customers and their demand. U.S. multinationals also take advantage of producing foods in developing countries, using inexpensive labor. Lower labor costs, as compared to those in developed countries, are an important factor in investment decisions.

Table 2 shows the calculated values of roots. The smaller root calculated for the estimated Euler equation lies in the required range between zero and one (0.146) and the larger root is greater than unity (1.068); they therefore comply with convergence requirements. The value of the smaller root, being close to zero, suggests very fast adjustment of investment in the food processing industries in Latin American countries. It is likely that U.S. multinationals simply buy already existing production facilities in foreign countries. In this case, the foreign investment consists of a simple transfer of funds and does not result in building new production facilities in most cases. Thus, the adjustment costs did not seem to slow the investment process significantly.

| Exchange Rate | Tax | GDP | FDT Openness | Wage | Interest Rate | Sales | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T = 10 | 0.34 | 0.46 | 0.09 | 0.40 | −1.21 | −0.87 | 1.73 |

| T = 10 | 0.95 | 4.21 | −1.81 | 1.79 | −5.05 | −3.63 | 7.25 |

| T = ∞ | 1.71 | 8.89 | −4.18 | 3.52 | −9.84 | −7.09 | 14.13 |

| Roots of the Euler Equation | λ1 = 0.146 | λ2 = 1.068 | |||||

Effects of the Shocks on Investment Decisions

The estimated coefficients do not directly show the effects of changes in exogenous variables on the FDI position of U.S. multinational firms because of the dynamic nature of the estimated model. Equations (5)–(8) represent the effects of shocks on FDI position. We multiplied these equations by the ratios of data means from each country's panel to show the effects of changes in exogenous variables (wages, interest rates, sales, and macro variables) on the FDI position in the form of elasticities. Since the model is dynamic, we calculated both temporary and permanent effects of shocks. Elasticities with respect to traditional variables that determine production costs (wages, interest rates, and sales) have expected signs (table 2). According to the estimations, an increase in real wages and real interest rates results in the reduction of direct investment capacity in a host country. This result is intuitive and consistent with the cost-minimizing behavior of the multinationals. However, the effects of a shock to interest rates, which represent the direct costs of capital, are not as prominent as the effects of the shock to real wage.

Demand factors, represented by real sales in a host country, are important in determining the FDI position of U.S. multinationals. An increase in demand requires more production capacity, and therefore more FDI.

The overall level of FDI as a share of GDP in a host country (FDI openness) has a positive effect on food processing investment levels, although the elasticities are not as high as those for most other variables. FDI openness indicates the general receptiveness of the host country to foreign capital.

Market size, proxied by real GDP, is positively related to food processing FDI in the short run but is negatively related to FDI in the medium and long run. The positive relationship is intuitive because U.S. multinationals initially prefer to invest in large rather than small markets. The negative relationships are possible because as the size of market increases in the medium and long run, there will be more competition and increases in wages and interest rates, implying that U.S. multinationals may be discouraged from increasing their FDI.

The tax levels in a host country are positively related to food processing FDI. Intuitively, high taxes should discourage foreign investment because of cost considerations. However, it may be the case that an economy-wide indicator of tax level does not properly represent tax policies that host countries' governments implement with respect to foreign investment. High taxes may signify governments' involvement in providing economic stability and creating a good investment environment. Finally, exchange rates have a positive effect on the FDI position.

Conclusions

A dynamic cost minimization model was developed to analyze U.S. foreign direct investment (FDI) in the food processing industries of nine Latin American countries. This study shows that the dynamic structure explains the investment process in food processing industries well. Estimation results reveal a relatively high speed of adjustment of FDI, indicating that U.S. food processing multinationals are quite flexible in terms of adjusting their production capacities. This can happen because multinationals buy existing production facilities instead of setting up their own, which can take more time and be more expensive.

Higher wages and interest rates have a negative effect on the FDI position of U.S. multinationals, while an increase in demand for output has a positive effect. FDI openness and the exchange rate were found to have a positive effect on U.S. FDI in food processing industries. U.S. multinationals are encouraged to invest in growing markets in the short run, but discouraged in the long and medium run, mainly because of increased competition and higher input costs with larger-sized markets in the medium and long run. Overall tax levels have a positive effect on the FDI position, possibly because high taxes may signify governments' involvement in providing economic stability and creating a good investment environment.