Canada's Agricultural Trade in North America: Do National Borders Matter?

Abstract

Canada and the United States are each other's largest trading partner. Trade in agricultural goods has grown continuously since the signing of the Canada—United States Trade Agreement in 1989. The trade agreement removed most tariffs on traded agricultural goods. However, many nontariff barriers remain. We estimate the border effects for a select group of agricultural commodities and find that the quantity traded is less than would be predicted under free trade.

The Canada—United States Trade Agreement (1989) or CUSTA, and the Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture or URAA (1995) are the two major trade agreements affecting the level of agricultural trade between Canada and the United States.1 The CUSTA removed most of the tariff and nontariff barriers on agricultural trade between the two countries. Some of the more contentious trade issues, such as the operation of the supply-managed system and the Canadian Wheat Board, were left to the URAA negotiations. Barichello et al. reviewed the effect of CUSTA on agricultural trade between the United States and Canada and concluded that trade was far from frictionless, even though many tariffs were lowered and some quantitative restrictions removed.

The CUSTA went into effect on January 1, 1989, and was aimed at increasing trade between Canada and the United States by removing tariff and nontariff barriers. CUSTA did not result in a set of harmonized external tariffs for Canada and the United States and thus created a Free Trade Area (FTA) rather than a Customs Union or a Common Market. Those sectors deemed able to compete in the FTA had their tariff protection removed immediately while others had it eliminated over a five- or ten-year period. Trade restrictions were left on some products such as sugar, dairy, and poultry. The CUSTA allowed for a snapback provision on fruits and vegetables in the form of a price-based tariff for a period of twenty years. The reduction in tariff and nontariff barriers was to lead to greater integration and reduced home consumption bias in the two economies. CUSTA's provisions were fully implemented as of January 1, 1998.

The North American Free Trade Agreement (1994) or NAFTA replaced the CUSTA to include Canada, Mexico, and the United States. The NAFTA will eliminate most tariff barriers and many nontariff barriers affecting U.S.—Mexico and Mexico—Canada trade over fourteen years, ending on January 1, 2008. The NAFTA did not make additional tariff reductions to U.S.—Canada agricultural and food trade (Appleton).

The URAA (1995) is the second trade agreement affecting the flow of agricultural goods and services between the United States and Canada. The URAA (1995) is a derivative of the General Agreement of Tariffs and Trade or GATT (1994). The multilateral GATT (1994) covers a wide range of goods and services but excludes most trade in agriculture products. With the URAA (1995), agriculture was partially brought under the discipline of the GATT (1994). The World Trade Organization (WTO) was created on January 1, 1995, by the member nations of the GATT. The function of the WTO is to deal with the rules of trade between nations. The debate over a further multilateral reduction in agricultural trade barriers will occur within the WTO.

The URAA (1995) reduced tariffs on agricultural products and the level of trade-distorting subsidies, particularly those deemed to be export subsidies. It also removed the quantitative restrictions on agricultural trade allowed under Article 11(2)c of the GATT (1948). This Article protected the Canadian supply-managed system from imports. Article 11(2)c was replaced with a system of tariff—rate quotas (Skully). Josling, Tangermann, and Warley found that the URAA (1995) only partially liberalized agricultural trade because it left some restrictive border measures in place, such as tariffs on dairy products.

Notwithstanding the trade agreements between Canada, Mexico, and the United States, a home consumption bias in Canada remains. McCallum found substantial bias in Canada when examining the level of aggregate merchandise trade between the United States and Canada for 1988. Using the 1993 U.S. Commodity Flow Survey (CFS), Hillberry tested the robustness of McCallum's finding. Hillberry states “…the CFS estimates of the “border effect” are almost exactly equivalent to those estimated by McCallum” (p. 1). In 1998, Helliwell (1998) reported that the home consumption bias in Canada had declined since the CUSTA, but it remains larger than what trade theory would predict. Anderson and van Wincoop suggest that substantial gains in trade and welfare are attainable from a further reduction in North American tariff and nontariff barriers. While they did not explicitly model trade in agricultural commodities, they report that large trade restrictions still exist at the Canada—U.S. border.

For 1984 and 1989, Cyrus reports that tariff and nontariff barriers have large Canada—U.S. border effects for most agricultural commodities. While the CUSTA and the URAA lowered tariff and nontariff barriers, trade friction remains an issue at the Canada—U.S border. The recent action of the Ranchers Cattlemen Action Legal Foundation (RCALF), the U.S.—Canada wheat disputes, and the tomato wars are three examples of the trade friction between the two countries. In 2000, RCALF brought both an antidumping and countervailing suit against Canadian live cattle imports into the U.S. market. While no permanent trade barrier resulted from this case, it demonstrates the pressures that lobby groups place on governments to restrict agricultural trade across the U.S.—Canada border. To date, no one has measured the Canadian home consumption bias in agricultural trade with Mexico.

This article provides an estimate of the border effect for agricultural trade between the United States and Canada, and Mexico and Canada in 1992–98. It is important to know how restricted agricultural trade is between countries and thus the potential welfare gains from further trade liberalization.

Tariff barriers, while the most visible, are not the only source of trade restriction. Nontariff barriers are also important and need to be reduced so that goods and services can move efficiently across national boundaries. We report large border effects for trade in some agricultural goods, such as dairy products, between Canada and the United States. A surprising result is that the Canadian border effects with Mexico are much lower than with the United States.

A second issue examined in this article is the symmetry of the border effect between agricultural imports into Canada and agricultural exports from Canada. This symmetry is examined for both Canadian—American and Canadian—Mexican trade. U.S. producers claim that Canada maintains agricultural marketing boards, which promote exports and restrict imports. Our conclusion is that the Canada—U.S. border effects are more pronounced for imports than exports (i.e., the two border effects are not symmetric in magnitude). Symmetry is more likely in the case of Canadian—Mexican agricultural trade.

We provide a short overview of Canada—U.S. and Canada—Mexico agricultural trade, followed by a brief discussion of the gravity model and the data used to estimate the gravity equation. The econometric results are presented along with a discussion of the estimates. We compare our results with the work by Cyrus, and examine how the border effect has changed for agricultural trade since the introduction of the CUSTA and NAFTA.

Agricultural Trade Patterns

Since 1992, the United States has increased its market share of Canadian agricultural imports and exports (table 1). Grain is the one Canadian agricultural export for which the United States is not the primary market. This is not surprising given that both the United States and Canada are major grain exporters. Canada does import a small amount of grain, mostly corn and rice, and the United States is the principal supplier.

| Exports Going to the US (%) | Imports Originating in the US (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Grain | Meat, Fish, and Dairy | Fruits and Vegetables | Other Agric. | Grain | Meat, Fish, and Dairy | Fruits and Vegetables | Other Agric. |

| 1992 | 12.0 | 55.8 | 63.6 | 46.6 | 86.5 | 38.0 | 53.1 | 68.7 |

| 1993 | 20.3 | 56.1 | 67.0 | 43.7 | 86.6 | 37.5 | 57.1 | 69.1 |

| 1994 | 25.9 | 58.3 | 73.4 | 37.4 | 91.7 | 38.7 | 54.5 | 68.0 |

| 1995 | 18.6 | 53.7 | 67.8 | 39.6 | 92.4 | 41.4 | 58.9 | 66.9 |

| 1996 | 17.0 | 55.2 | 70.5 | 43.1 | 89.7 | 40.7 | 57.8 | 80.5 |

| 1997 | 19.5 | 60.6 | 75.6 | 47.7 | 87.9 | 42.1 | 58.7 | 65.7 |

| 1998 | 17.5 | 66.3 | 83.0 | 49.4 | 82.0 | 42.3 | 61.9 | 62.4 |

- Source: Statistics Canada.

With such crops as citrus and winter vegetables, California and Florida are the largest exporters of agricultural products to Canada. Massachusetts is the destination for the largest share of Canadian agricultural exports. In Canada, Ontario is the largest province in terms of agricultural imports and exports. On a per capita basis, however, the Prairie Provinces are the largest exporters of agricultural commodities.

Inter-provincial agricultural trade over 1992–98, was larger than agricultural trade with the United States, averaging Cdn$17 billion per year versus Cdn$14 to the United States (Statistics Canada). This is surprising given the perceived wisdom that north—south trade is the most important to Canadian farmers and processors. Most of the Canadian provinces produce similar agricultural products for export, such as meat and grains, and import products like citrus, nuts, and winter vegetables.

Canadian—Mexican agricultural trade was much smaller than Canadian—American agricultural trade (table 2). Canada exports a small quantity of grain and oilseeds to Mexico and imports agricultural products such as winter vegetables from Mexico. Since the NAFTA, Canadian imports of fruits and vegetables from Mexico have doubled in percentage terms,2 highlighting the importance of examining the agriculture trade flows between Canada and Mexico.

| Exports Going to Mexico (%) | Imports Originating in Mexico (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Grain | Meat, Fish, and Dairy | Fruits and Vegetables | Other Agric. | Grain | Meat, Fish, and Dairy | Fruits and Vegetables | Other Agric. |

| 1992 | 3.6 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 2.8 |

| 1993 | 4.1 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 3.4 |

| 1994 | 4.4 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 3.7 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 3.5 |

| 1995 | 2.9 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 4.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 4.5 |

| 1996 | 3.2 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 4.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 4.9 |

| 1997 | 3.5 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 4.6 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 4.6 |

| 1998 | 4.6 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 5.4 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 4.9 |

- Source: Statistics Canada.

Gravity Trade Model

Tinbergen was the first to use the gravity model to explain international trade flows. However, it was Anderson that developed a solid theoretical foundation for the gravity model. Feenstra, Markusen, and Rose provide an excellent review of the theoretical foundations of the gravity model. The gravity model has been used to measure the impact of policy changes on trade flows including regional trade agreements (Bayoumi and Eichengreen), the economic effects of open versus closed trade blocs (Wei and Frankel), the relationship between increased trade and economic growth (Frankel and Romer), and the impact of uncertainty on trade and home bias (Anderson and Marcouiller). The gravity model has also been used to estimate the home bias in the European Union countries (Nitsch) as well as between Canada and the United States (McCallum; Helliwell (1998); Stein and Weinhold). However, there remains a concern with how well the gravity model explains trade flows when monopolistic competition exists (Hummels and Levinsohn); we do not investigate this topic.

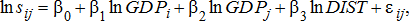

(1)

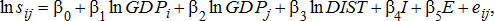

(1) (2)

(2)The border variable takes on a value of 0 when trade occurs within the home country and 1 otherwise. If the border has no effect on trade flows, β4 will not be significantly different from 0. The anti-log of β4 is an estimate of the border effect.

(3)

(3)Data

The majority of the data (all data observations are annual) for this study were obtained from different sources within Statistics Canada. The first major data set, inter-provincial trade flows, was obtained from the Input-Output Division of Statistics Canada. This is a unique data set because no other country keeps track of trade among its own regions. The data consist of input—output matrices of trade flows among the provinces and the rest of the world for a wide range of product groups, including agriculture.

Statistics Canada removed all transshipments within Canada from the input—output tables, i.e., wheat destined for Japan (through the Port of Vancouver) from Manitoba does not show up as wheat exported from Manitoba to British Columbia. Four categories of agricultural trade were available from the inter-provincial data set for 1992–98 and were used in this study. They are: (a) grains; (b) meat, fish, and dairy; (c) fruits, vegetables, and other food; and (e) other agriculture (see table 1 footnote for an explanation of the categories).

Only annual input—output data are available so we cannot break out seasonal trade effects for such commodities as fresh vegetables and fruit. This level of aggregation does not allow a completely clean measure of the border effect for some products. For example, processed meat and dairy trade data are aggregated by Statistics Canada, which makes an accurate measure of the border effects for these commodities nearly impossible. On occasion, Statistics Canada omitted entries within a particular matrix because there were too few observations (confidentiality) or the trade flows were near zero. In order to maintain as large a data set as possible, on the advice of Statistics Canada, the RAS method3 (Stone) was used to fill in these values.

The second major data set consisted of the value of trade among each of the Canadian provinces and each of the 30 selected American states, and Mexico.4 These data were obtained using software from Statistics Canada.

The data set for predicting the border effect between the United States and Canada for each of the four category groups contained 9 (trade flows) × 10 (provinces) = 90 observations provincially,5 plus 10 (provinces) × 30 (U.S. states) × 2 (trade flows) = 6006 observations for U.S. state data. The data set used for predicting the border effect between Mexico and Canada contained 9 (trade flows) × 10 (provinces) = 90 observations provincially, plus 1 (country) × 10 (provinces) × 2 (trade flows) = 20 observations for Mexico. This was not always the case though, as will be shown in the estimated regressions because cases of zero trade with both the United States and Mexico were omitted.7

Distance data for inter-provincial trade and province—state trade were calculated using the great circle method, which is the weighted average of the latitudes and longitudes of the three most populous cities (Cyrus). This was done to create an economic center for each of the regions.8

The final data set, gross domestic product (GDP), was obtained from Statistics Canada's publication (Provincial Economic Accounts 1998 Annual Estimates) for the Canadian provinces. The data for the individual states of the United States were obtained from the United States Department of Commerce's (Bureau of Economic Analysis) online publication. Mexican GDP data were obtained from the International Monetary Fund's CD-ROM, (International Financial Statistics 1999). All the data collected in value terms were converted to Canadian dollars using official exchange rates and deflated to 1992 values.

Econometric Results

The United States—Canada Border

Table 3 gives the estimated gravity equation for total agricultural trade for years 1992—98 between Canada and the United States (i.e., all four trade categories combined). The estimated border effect for the year 1992 is 113.14. That is to say, after accounting for the difference in the size of the market, and given that British Columbia is equidistant from Ontario and Michigan, British Columbia is 113.14 times more likely to trade agricultural goods with Ontario than with Michigan.

| Observations | 651 | 647 | 639 | 628 | 625 | 639 | 643 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimation Method | OLS | OLS | OLS | OLS | OLS | OLS | OLS |

| Dependent | Trade | Trade | Trade | Trade | Trade | Trade | Trade |

| Variables | Flow | Flow | Flow | Flow | Flow | Flow | Flow |

| ln(TF × m) | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 |

| Constant | 8.98 | 9.14 | 9.58 | 10.55 | 10.56 | 8.87 | 8.98 |

| (7.91) | (7.95) | (8.50) | (8.85) | (9.50) | (7.33) | (7.62) | |

| ln(GDPm) | 1.22 | 1.22 | 1.18 | 1.11 | 1.17 | 1.27 | 1.30 |

| (22.85) | (22.32) | (22.39) | (19.58) | (21.91) | (22.71) | (24.21) | |

| ln(GDP×) | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.69 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.65 |

| (14.82) | (14.58) | (14.18) | (14.36) | (13.99) | (12.88) | (13.11) | |

| ln(DIST + m) | −1.58 | −1.58 | −1.54 | −1.65 | −1.60 | −1.52 | −1.59 |

| (−15.75) | (−15.62) | (−15.60) | (−15.88) | (−16.36) | (−14.08) | (−15.32) | |

| BORDER | −4.73 | −4.72 | −4.57 | −4.47 | −4.43 | −4.52 | −4.52 |

| (−22.05) | (−22.32) | (−22.15) | (−20.46) | (−21.68) | (−20.02) | (−20.61) | |

| R2-adjusted | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.59 | 0.62 |

| SEE | 1.72 | 1.75 | 1.69 | 1.78 | 1.67 | 1.85 | 1.78 |

| Border Effect | 113.1 | 112.5 | 96.8 | 87.4 | 84.3 | 91.6 | 91.4 |

- Source: Authors' estimates.

The aggregate border effect drops from a high of 113.14 in 1992 to 84.3 in 1996 before increasing to 91.4 in 1998. A border effect of 91.4 is large and suggests that agricultural trade between the two countries is more restricted than expected given the trade agreements. Part of the reason for the high border effect may stem from the aggregation of all agricultural trade into one trade flow measure. The agricultural trade policy regime between Canada and the United States is composed of different tariff and nontariff barriers depending upon the commodity (e.g., the tariff on trade in dairy products is very different from the tariff on trade in live cattle).

The estimated coefficients on the GDP variable are elasticity values. The elasticity for the importing region's GDP is greater than the elasticity for the exporting region's GDP (the hypothesis that they are symmetric has a probability of 0.001 using the Wald Test). Thus, demand pull has a greater impact on increasing agricultural trade than supply push.

Table 4 presents the different impacts of the Canada-U.S. border on imports and exports (the results of equation (3)). As expected, the sign of the parameter was negative for both the import and export variables. The null hypothesis is that the border effect would be symmetric i.e., coefficients β4=β5. This hypothesis is rejected 90% of the time in all the years but 1992 and 1995. The implication is that imports into Canada from the United States are more restricted at the border than are exports from Canada to the United States. This might come as a surprise to Canadian producers who often claim their agricultural markets are more open than those in the United States. The aggregation of agricultural commodities into one trade measure again may be part of the reason for this result. To test if aggregation is the source of the difference between the import and export effects, we considered a more disaggregate grouping of agricultural trade between the two countries.

| Observations | 651 | 647 | 639 | 628 | 625 | 639 | 643 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimation Method | OLS | OLS | OLS | OLS | OLS | OLS | OLS |

| Dependent | Trade | Trade | Trade | Trade | Trade | Trade | Trade |

| Variables | Flow | Flow | Flow | Flow | Flow | Flow | Flow |

| ln(TF × m) | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 |

| Constant | 8.98 | 9.12 | 9.54 | 10.55 | 10.48 | 8.84 | 8.96 |

| (7.91) | (7.95) | (8.52) | (8.85) | (9.49) | (7.37) | (7.62) | |

| ln(GDPm) | 1.17 | 1.14 | 1.12 | 1.07 | 1.10 | 1.18 | 1.21 |

| (20.44) | (19.73) | (19.59) | (17.40) | (19.40) | (19.53) | (20.68) | |

| ln(GDPx) | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.74 |

| (14.15) | (14.26) | (13.95) | (13.61) | (13.58) | (12.84) | (13.32) | |

| ln(DIST × m) | −1.58 | −1.58 | −1.54 | −1.65 | −1.60 | −1.52 | −1.59 |

| (−15.75) | (−15.62) | (−15.60) | (−15.88) | (−16.36) | (−14.08) | (−15.32) | |

| Import (IM) | −4.85 | −4.95 | −4.80 | −4.60 | −4.70 | −4.88 | −4.86 |

| (−21.56) | (−21.46) | (−21.37) | (−19.30) | (−21.01) | (−19.87) | (−20.31) | |

| Export (EX) | −4.60 | −4.50 | −4.34 | −4.34 | −4.19 | −4.16 | −4.18 |

| (−20.33) | (−19.61) | (19.32) | (−18.15) | (−18.96) | (−17.07) | (−17.55) | |

| p-value | 0.160 | 0.015 | 0.010 | 0.172 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.001 |

| (IM = EX) | |||||||

| R2-adjusted | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.60 | 0.62 |

| SEE | 1.72 | 1.75 | 1.68 | 1.78 | 1.67 | 1.85 | 1.78 |

- Source: Authors' estimates.

To approximate the different border effects among the traded commodity groups, we estimated a gravity equation for each of the four-trade groupings (table 5). The border effect for grains increased after 1996. This is partly due to the voluntary export restriction placed on Canadian wheat exports to the United States in 1995. Due to the poor U.S. wheat crop in 1995, Canadian exports surged. In response to tariff threats from the U.S. government, the Canadian government instructed the Canadian Wheat Board to limit sales to the U.S. market. The Canadian Wheat Board has since increased sales to the U.S. market.

| Grains | Meat, Fish, and Dairy | Fruits and Vegetables | Other Agric. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimation Method | OLS | OLS | OLS | OLS |

| 1992 Border effect | 24.9 | 114.9 | 134.4 | 45.7 |

| p-value (IM = EX) | 0.001 | 0.146 | 0.279 | 0.925 |

| 1993 Border effect | 20.5 | 104.8 | 126.4 | 40.0 |

| p-value (IM = EX) | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.679 | 0.943 |

| 1994 Border effect | 20.2 | 115.1 | 137.3 | 39.6 |

| p-value (IM = EX) | 0.001 | 0.066 | 0.775 | 0.553 |

| 1995 Border effect | 23.2 | 121.9 | 119.3 | 45.5 |

| p-value (IM = EX) | 0.010 | 0.081 | 0.805 | 0.239 |

| 1996 Border effect | 41.7 | 100.1 | 83.5 | 24.7 |

| p-value (IM = EX) | 0.001 | 0.144 | 0.113 | 0.083 |

| 1997 Border effect | 37.9 | 120.7 | 90.5 | 31.6 |

| p-value (IM = EX) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.019 | 0.006 |

| 1998 Border effect | 58.6 | 152.7 | 80.8 | 29.7 |

| p-value (IM = EX) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.006 |

- Source: Authors' estimates.

The border effect on “other agriculture” declined sharply since 1992. This result is due to the increased coordination of the two governments on health and inspection regulations, such as preinspection for trade in live animals. However, the border effect for “meat, fish, and dairy” has not declined since 1992, which is the result of the high tariffs for these products in both countries (Canada maintains high tariffs for supply-managed products).9 Canada has a 4–5% minimum access commitment for dairy products. As shown in table 6, the tariff on over-quota imports (i.e., TRQ) of dairy products is in the range of 250%. The United States has a TRQ of 42.5% on dairy products (table 6). Because the tariffs on dairy products were not included in the CUSTA, the tariffs reported here are for both Canada—U.S. trade, as well as for trade with other countries. These high tariff rates are consistent with the larger border effects reported for the category “meat, fish, and dairy.”

| United States | Canada | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector | Nominal Tariff | Effective Rate of Protection | Nominal Tariff | Effective Rate of Protection |

| Unit | % | |||

| Fruits and vegetables | 4.7 | 6.4 | 4 | 7 |

| Live poultry | 0.6 | 1.1 | 202 | 305.2 |

| Dairy products | 42.5 | 158.5 | 252 | 680.1 |

| Sugar products | 53.4 | 442.8 | 4.9 | 5.5 |

- Source: Meilke et al.

- * These products were exempt from the tariff reductions in the CUSTA and left to the URAA. Fruitsand vegetables had tariffs removed but were granted a snapback price-based tariff protection. Thenominal tariff and effective rate of protection were calculated using imports from all countries, notjust the United States or Canada.

Within Canada, inter-provincial trade is especially large for dairy products like cheese. Most of this trade is moving to other provinces from Quebec and Ontario because they have the largest industrial milk quota (over 70% between the two provinces). If the tariff barriers on dairy products were lowered between the United States and Canada, some of this trade would occur between the two countries rather than just within Canada. While the net trade in dairy products may not increase significantly with freer trade, we expect some of the trade flows would change due to lower transportation costs. For example, Manitoba may import cheese from Wisconsin rather than Quebec because Manitoba is closer to Wisconsin. Similarly, New York may import dairy products from Quebec as well as from California.

The border effect for the “fruits and vegetables” category declined after 1994; however, it remains unexpectedly high. The explanation here is difficult because the CUSTA removed tariffs on fruits and vegetables. This suggests the border effects are measuring some nontariff barriers. The first explanation is that the snapback provision restricts companies from aggressively entering markets in the other country for fear of triggering a tariff. Secondly, the seasonal production of fruits and vegetables makes provinces like Ontario and British Columbia competitive with the United States in the summer months. In winter, Canada imports fruits and vegetables from the United States and Mexico. Our annual model is not able to pick up this difference. Another possible explanation is that it is difficult for new firms to enter because the fruit and vegetable sector is highly vertically integrated.

The second result from the gravity equation shown in table 5 is the probability that the estimated parameters on the import and export variable are symmetric. (In all cases, the export parameter was larger; however, this is not shown in table 5.) For grains, the probability of the two parameters being symmetric was rejected 99% of the time. This would appear to imply that it is easier for Canadians to export grains into the U.S. market than vice versa. This is a common complaint made by U.S. grain producers; our results support their view.

The three remaining trade groupings have mixed results on the symmetry of the import/export border effects. “Fruits and vegetables” and “other agriculture” are the two trade groupings where the border effect appears to be symmetric. However, by 1997, the imports of all agricultural products from the United States faced a more restricted border than did exports from Canada into the U.S. market.

There are at least two reasons why imports and exports have different border effects. First, Canada may have border restrictions that reduce the flow of agricultural imports (see table 6). Marketing boards are a prime suspect in this category. The second reason is that Canadians have better networks in the U.S. market than U.S. exporters have in the Canadian market. Helliwell (2001) argues that because the U.S. market is more important to Canada than the Canadian market is to the United States, social networks are stronger from Canada to the United States than vice versa. If it is the case as Helliwell (2001) suggests, imports would be more restricted than exports at the Canada—U.S. border.

The Mexico—Canada Border

Table 7 shows the estimated model for Mexican—Canadian total agricultural trade (we did not estimate a separate equation for each of the four categories because of the scarcity of trade in some years). The border effect for total agricultural trade between Mexico and Canada fell from 50 in 1992 to 17 in 1998 or by about two-thirds in seven years. Most of the reduction in border effect occurred after 1994, most likely as a result of the NAFTA.

| Observations | 107 | 108 | 108 | 109 | 108 | 109 | 107 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimation Method | OLS | OLS | OLS | OLS | OLS | OLS | OLS |

| Dependent | Trade | Trade | Trade | Trade | Trade | Trade | Trade |

| Variables | Flow | Flow | Flow | Flow | Flow | Flow | Flow |

| ln(TF × m) | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 |

| Constant | 7.76 | 7.74 | 7.47 | 7.44 | 8.47 | 8.12 | 8.50 |

| (5.09) | (4.49) | (4.64) | (4.35) | (6.13) | (5.06) | (5.65) | |

| ln(GDPm) | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| (11.29) | (10.45) | (11.39) | (10.22) | (11.60) | (10.62) | (11.43) | |

| ln(GDP×) | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.82 |

| (11.79) | (9.91) | (10.26) | (10.10) | (11.67) | (10.35) | (9.97) | |

| ln(DIST × m) | −1.29 | −1.26 | −1.20 | −1.23 | −1.19 | −1.24 | −1.22 |

| (−9.36) | (−8.13) | (−8.24) | (−7.99) | (−9.52) | (−8.50) | (−9.01) | |

| BORDER | −3.92 | −4.31 | −4.28 | −3.80 | −2.98 | −3.52 | −2.84 |

| (−10.8) | (−10.79) | (−11.48) | (−10.33) | (−9.93) | (−10.23) | (−8.50) | |

| R2-adjusted | 0.751 | 0.715 | 0.736 | 0.729 | 0.768 | 0.743 | 0.730 |

| SEE | 1.13 | 1.27 | 1.19 | 1.26 | 1.02 | 1.19 | 1.11 |

| Border Effect | 50.4 | 74.4 | 72.2 | 44.7 | 19.7 | 33.8 | 17.1 |

- Source: Authors' estimates.

An explanation for the remaining border effect (i.e., in addition to the remaining tariffs) could be that much of Mexican—Canadian agricultural trade is transshipped through the United States. There may be transaction costs associated with the transshipment of goods that create a “like” border effect, which has nothing to do with the Mexican—Canadian border. Thus, the border effect reported in this article for the Canada—Mexico agricultural trade should represent an upper estimate.

Table 8 reports the border effect for imports into Canada from Mexico and exports from Canada to Mexico. In the case of Mexican—Canadian agriculture trade, the border has a symmetric effect on imports and exports. There are at least two reasons for the symmetry of imports and exports of agricultural trade between the two countries. First, Canada imports winter vegetables and fruits from Mexico and exports grains and meat products. This trade does not lead to rent-seeking activities because there is little competition in the marketplace arising from the trade. Second, the business networks between Mexico and Canada are possibly more balanced than between the United States and Canada because the sizes of the economies are similar.

| Observations | 107 | 108 | 108 | 109 | 108 | 109 | 107 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimation Method | OLS | OLS | OLS | OLS | OLS | OLS | OLS |

| Dependent | Trade | Trade | Trade | Trade | Trade | Trade | Trade |

| Variables | Flow | Flow | Flow | Flow | Flow | Flow | Flow |

| ln(TF × m) | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 |

| Constant | 7.76 | 7.74 | 7.47 | 7.44 | 8.47 | 8.12 | 8.50 |

| (5.09) | (4.49) | (4.64) | (4.35) | (6.13) | (5.06) | (5.65) | |

| ln(GDPm) | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.89 |

| (11.29) | (9.62) | (10.47) | (10.22) | (11.60) | (10.62) | (10.97) | |

| ln(GDP×) | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.84 |

| (11.79) | (9.74) | (10.26) | (10.10) | (11.67) | (10.35) | (10.29) | |

| ln(DIST × m) | −1.29 | −1.26 | −1.20 | −1.23 | −1.19 | −1.24 | −1.22 |

| (−9.36) | (−8.13) | (−8.24) | (−7.99) | (−9.52) | (−8.48) | (−9.11) | |

| Import (IM) | −4.10 | −4.69 | −4.80 | −3.88 | −3.01 | −3.74 | −3.36 |

| (−8.44) | (−8.97) | (−9.94) | (−7.87) | (−7.27) | (−8.12) | (−7.99) | |

| Export (EX) | −3.76 | −3.92 | −3.74 | −3.73 | −2.96 | −3.32 | −2.84 |

| (−8.05) | (−7.50) | (−7.73) | (−7.83) | (−7.79) | (−7.49) | (−5.15) | |

| p-value (IM = EX) | 0.586 | 0.259 | 0.094 | 0.802 | 0.932 | 0.477 | 0.049 |

| R2-adjusted | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| SEE | 1.13 | 1.27 | 1.19 | 1.26 | 1.02 | 1.19 | 1.09 |

- Source: Authors' estimates.

Comparison with Other Results

Cyrus estimated the border effect of agricultural trade between Canada and the United States for 1984 and 1989. Table 9 shows her results and indicates that in the 1980s, the border effect was larger than estimated in our research. The commodity groupings are different because of the change in the data collection techniques by Statistics Canada, making a clean comparison of the results from the two models difficult.

| Industry | 1984 | 1989 |

|---|---|---|

| Cereal and bakery products | 273.14 | 566.8 |

| Dairy products | 301.87 | 468.72 |

| Sugar products | 550.04 | 376.15 |

| Meat products | 146.94 | 82.27 |

| Fruits and vegetables | 112.17 | 172.43 |

| Fish products | 3.9 | 4.26 |

- Source: Cyrus (2000).

Cereal and bakery products is one of the categories of agricultural trade that has experienced a large reduction in border effects. Our estimates are an order of magnitude lower than those reported by Cyrus. Similarly, comparisons of our estimates with those of Cyrus indicate that fruits and vegetables were more likely to be traded between the United States and Canada in 1998 than in 1989. This suggests a major reduction in the border effect. Because the tariffs remain high on supply-managed products, such as dairy and sugar, the border effect for these commodities is still large. Clearly, the border has become more open and greater access is possible.

The trade impact of the CUSTA is only one explanation of the reduced border effects between the United States and Canada. Increased globalization is an additional cause. One aspect of greater globalization is the increase in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Wei and Frankel make the point that FDI leads to more open markets. Because multinational corporations want to trade among their own plants to achieve economies of scale and scope, they do not want border restrictions that increase the cost of intra-firm trade. For example, the expansion of the meat industry in southern Alberta by U.S.-based multinational corporations (i.e., Cargill) is part of the cause for the lower border effect in the 1990s.

Conclusions

The results of this study show that the border effects for agricultural trade between the United States and Canada and between Mexico and Canada have declined over the period 1992–98. Canadian agricultural trade has a lesser home consumption bias than in 1984, with the highly protected supply-managed sector being the one major exception.

The first surprising result is that the border effect for agricultural trade between Canada and the United States is larger than between Canada and Mexico. More work is needed to explain this difference. As mentioned earlier, one explanation may be the rent-seeking behavior of the lobby groups and the politicians on both sides of the United States—Canadian border.

A second surprising result is that Canadian exports move across the U.S.—Canada border more easily than imports into the Canadian market from the United States. This result suggests that Canada has nontariffs barriers to restrict trade with the United States. The state trading marketing boards are the prime suspects. Both the United States and Canada have effective domestic industry groups that lobby politicians for economic protection. This economic protection often comes in the form of border measures that reduce trade.

The Canadian border is still important. Agricultural trade with the United States and Mexico is by no means free and home consumption bias does exist in Canada. It is not surprising that NAFTA did significantly reduce the border effect for agricultural trade. The critics who claim NAFTA did not increase agricultural trade appear to be wrong. Progress has been made toward freer agricultural trade in North America but there are still miles to go before the market is a seamless trading entity.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the helpful comments of a reviewer and co-editor Susan Offutt. Kathryn Lipton made many useful editorial improvements and we thank her. The usual caveats apply.