The Dayton legacy: baselines, benchmarks, climate, disturbance and proof

In a world full of creative, thoughtful, sincere scientists, there are a rare few who stand out, sometimes for the remarkable leap in understanding that comes from their work, sometimes for their ability to transform the human love of nature into a greater good, and sometimes for their dedication to educating the next generation, be they students, regulators, politicians or the public. Professor Paul K. Dayton belongs to an even more select group, the scientist who combines all of the above and maintains both his humility and humanity. Over more than four decades he has researched, taught, philosophized and assisted others in the endeavor we call marine ecology, and he continues to do so. For most of us working in this field, such efforts might encompass a few ecosystems, taxa, or realms. For Dayton, there are many ecosystems, taxa and spheres of influence. His work has been truly international in terms of the range of habitats studied, collaboration, inspiration and respect. Paul Dayton’s research has taken place in Antarctica, temperate kelp forests, rocky shores, and wetlands, marine protected areas, tropical reefs, the pelagic realm, continental shelves and even the deep sea. His study organisms range from kelps and vascular plants to meiofaunal, macrofaunal and megafaunal invertebrates, to fishes and whales. And his influence resonates from the towers of Academia to non profits, local, state and federal government and international commissions.

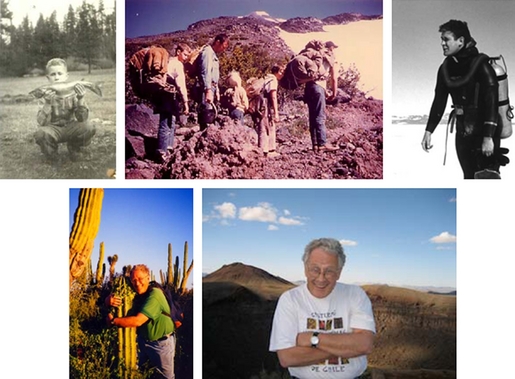

Paul Kuykendall Dayton (PKD) has experienced and loved the natural environment from an early age and throughout his life (Fig. 1). He was educated in Oregon and Arizona and received his PhD in 1970 from the Zoology Department at the University of Washington. He has been a professor at Scripps Institution of Oceanography since 1971. Over the years, Dayton has received numerous accolades, honoring his contributions to the field of marine ecology and marine conservation (Table 1). Underlying these prizes are a series of exceptionally influential publications. The earliest of his papers (Dayton 1971, 1975) derive from field experiments on the rocky shores of Washington; these shifted the world view of marine structuring agents from a competition focus to embrace various forms of disturbance and facilitation. His work is not simply a theoretical construct of how nature should work, but uses observational and manipulative experimental approaches to define the richness of nature.

Dayton’s love of nature, in youth and maturity.

| • Louise Burt Award for excellence in oceanographic writing, Oregon State University, 1971 |

| • George Mercer Award, Ecological Society of America, 1974 |

| • Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1985 |

| • PEW Scholar in Conservation and the Environment, 1995 |

| • Scripps Institute of Oceanography E.W. Scripps Associates Community Outreach Award, 1997 |

| • Sigma Xi Distinguished Lecturer, 1997–1998 |

| • WS Cooper Award, Ecological Society of America, 2000 |

| • Recognition of Merit for accomplishments in Marine Science, Aquarium of the Pacific. 2002 |

| • Scientific Diving Lifetime Achievement award, American Academy of Underwater Science, 2002 |

| • California Legislature Assembly Resolution recognizing contributions to marine conservation, 2003 |

| • Winner, 2003 UCSD Faculty Research Lecturer Award |

| • E. O. Wilson Award Naturalist Award, American Society of Naturalists, 2004 |

| • NOGI Award in Science. The Academy of Underwater Arts and Sciences. 2005 |

| • Ramon Margalef Prize in Ecology and Environmental Science, Barcelona, Spain 2006 |

| • Lifetime Achievement Award, Western Society of Naturalists, 2007 |

| • Scripps Institution of Oceanography Graduate Teaching Award 2007–2008 |

While Paul was not the first to dive under the ice, he was among the first to conduct a concerted research program that saw him and his dive buddies spending many hours diving, measuring, counting, caging and freezing in Antarctica. A series of papers on Antarctic benthos (Dayton et al. 1969, 1974; Oliver & Dayton 1977; Dayton 1989) explore the roles of biological interactions, productivity and climate in structuring communities with a level of insight yet to be repeated. His love of Antarctica continues to this day (Fig. 2). Dayton’s contributions to understanding kelp forest dynamics reflect his penchant for defining and tackling big problems with large datasets collected with extended effort. Dayton et al. (1992, 1999) reflect the necessity of examining large space and time scales to grasp biological, physical and climate interactions in structuring this key coastal ecosystem. It took many years for some who saw these scaling issues as a problem that challenged the significance of their small and elegant experiments to catch up with this broader perspective. As a whole, Dayton’s work sets major global research agendas over a range of systems: in rocky shore ecology (1970s), in Antarctica (1980s), in linking oceanography to benthic ecology (1990s) and in attention to fishing impacts (2000s). Even ecological mechanisms in the deep sea have received major scrutiny by Dayton (Dayton & Hessler 1972; Levin & Dayton 2009). His earliest work is as relevant today as it was when first carried out, and the continued citations bear testimony to this.

Dayton in Antarctica in austral summer 2010.

Conducting insightful ecological experiments is hard enough but Dayton shows us how respect and fame can be used for good. Dayton tackles the world’s big problems; conservation, fishing impacts, coastal habitat restoration and biodiversity are among these. In the world of conservation and resource management, Dayton et al. (1995), Dayton (1998), Dayton et al. (1998) and Dayton (2003) stand out as landmarks in raising awareness of key issues. Examples include the damaging if unintended ecosystem effects of fishing, the burden of proof needed to balance profit against our natural heritage, the sliding baselines that slur our judgment and value of nature, and the fundamental importance of natural science. His impact on research agendas and policy development has been enhanced through his service with organizations such as the International Council for Exploration of the Sea, the (US) National Academy and National Research Council panels and the Marine Mammal Commission.

Dayton’s approach to teaching is one of lighting the candle of inspiration and self-enquiry. His love of nature and infinite curiosity are manifest in many ways. For many decades he nurtured and guided with tremendous time and energy the UC San Diego Reserve System, protecting, expanding and making accessible to researchers and students a network of priceless protected terrestrial and marine ecosystems. The SIO 275A course ‘Natural History of Coastal Habitats’, which he has taught for over 35 years at Scripps, reflects Paul Dayton’s dedication to transmitting the glory of the natural world to his students. His unbounded knowledge about species preferences, interactions and life histories is conveyed in visits to mudflat, rocky shore, forest, desert, and chaparral settings (Fig. 3). The camaraderie that comes from getting stuck waist deep in mud, drenched in downpours, or sidelined by washed out roads reinforces the respect of students for the power of nature, the importance of humor and the fragility of life. He has touched students at all levels and in all walks of life, imbuing within them the value of natural history, the importance of the historical literature, the fragility of coastal ecosystems and the importance of acting on behalf of nature. He teaches about the philosophical and ethical issues that face scientists and the environmental policy issues that ecologists are increasingly asked to inform upon. His teaching methods include passionate lectures full of imagery, field trips that give students an appreciation for the importance of natural history, and stimulating discussion and debates. His role as teacher and mentor is not restricted to his home university or country, but is truly international. Beyond Academia he has devoted considerable energy to discussing environmental issues and, in particular, fishing impacts at a variety of public meetings. He has made many trips to Alaska and Arizona to talk about marine ecology in high schools and on reservations, and has arranged a cultural exchange between Hopi teenagers from Arizona and native youth from the Pribiloff Islands (Alaska).

Natural history class in action.

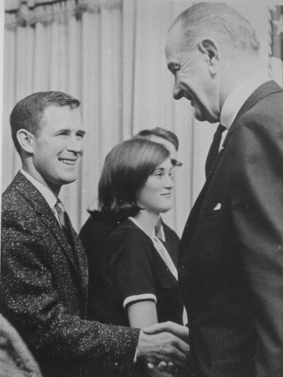

Dayton the man is as interesting as Dayton the legend, or perhaps they are the same. Few scientists have the hubris needed to make their pets coauthors, to put pictures of themselves with the president in their dissertations (to fulfill the University’s thesis page requirements) (Fig. 4), feed their students Tequila stew (Fig. 5) or to show photographs of naked women in their talk on soft bottoms. Even fewer have had their hindside immortalized on T shirts that bring hundreds of dollars at auction. Many have benefited from Paul’s humility, generosity, humor and readiness to see expertise in others.

A page in his dissertation: Dayton meets the President of the United States, Lyndon B. Johnson.

Dayton serving Tequilla Stew.

His regular visits over the course of 30 years to the Bubble in the Pinacates, Mexico (Fig. 6) has generated time series records of cactus growth, packrat middens, rainfall and other environmental variables. The many friends and associates that Dayton has introduced to this magnificent environment all take away a new appreciation for the beauty and fragility of the desert.

Dayton at the Bubble, Pinacates, Mexico.

The papers in this volume are dedicated to Professor Dayton in modest but sincere recognition of his ongoing contributions to field-based investigations and theory in marine ecology, for their significant impacts on policy and society and for his abilities to ignite and impassion students and the general public with the wonders of the natural world and the need to care greatly for them. The volume papers are written by Paul Dayton’s children, former graduate students, post docs and, in a few cases, his friends and fans. They represent the diversity of ideas, themes, approaches and ecosystems Paul has championed over the years.

The volume begins with reflections provided by his offspring on Paul Dayton’s uncanny ability to observe nature and how it has affected their lives (Dayton and Dayton, this volume). This theme is extended by Talley et al. (this volume) who, through documentation of the Ocean Leaders program, demonstrate the value of engaging youth in natural history and marine science. Their results reflect the strength of partnering between science and non-profit organizations, an approach that has benefited from the mentorship and inspiration of Dayton.

The work of Hammerstrom et al. (this volume) addresses a subject near and dear to Dayton’s heart – soft bottom diversity. They consider long-standing paradigms about diversity and the deep sea, and discuss the importance of species density, documenting the highest values for the central CA margin at the shelf-slope break.

Several of the papers address the role of disturbance by humans with manipulative experiments and time series studies. Huff (this volume) examines human trampling impact in rocky shore turf invertebrates, demonstrating major effects as well as resilience. Klinger and Fukuyama (this volume) also examine dynamics and resilience of intertidal communities to disturbance. Their long time series (12 years) and manipulative disturbances document resilience in fucoid populations in the Gulf of Alaska. Invasion provides a different type of disturbance, but one that is equally potent. Lorenti et al. (this volume) explore effects of the alien macroalga Caulerpa racemosa invasion on the soft-bottom macrobenthos in the Gulf of Salerno (Italy), describing patterns before and after algal colonization of the habitat. The role of macrophyte architecture and dynamics in structuring the benthos is one of the many topics addressed by Dayton. Sala and Dayton (this volume) also explore plant–animal interactions, quantifying herbivore-kelp interaction strength in the Point Loma (San Diego) kelp forest. All of these papers highlight the critical role of plant–animal interactions in structuring coastal ecosystems.

Global warming emerges as a theme in several papers. The importance of integrating environment, understanding changing conditions and potential use of environmental proxies (in this case temperature) to understand shifts in ecosystems in Australia (Hobday, this volume) echoes the work on shifting baselines and oceanographic forcing of kelp forests by Dayton (1998). Atmospheric warming will increase the rate of iceberg calving. Thrush and Cummings (this volume) invoke disturbance on a massive scale, with a time series showing iceberg effects on Antarctic benthos in the Ross Sea, where Dayton’s seminal studies were done. They document changes in the regional sea ice regime and oceanographic conditions that affect megafaunal benthic communities. They generate mechanistic understanding important for interpreting future climate change consequences for the Antarctic biota.

Dayton and his students and post docs have worked in wetlands for many decades. In the only wetland paper in the volume, Currin et al. (this volume) use stable isotopes to document the early trophic dynamics of the Stribly marsh (formerly the Crown Point Mitigation Site), a restored salt marsh that Dayton was instrumental in designing and acquiring for the UC Reserve System. The authors document the importance of cyanobacteria in supporting the macrofauna, but also define strong spatial and temporal heterogeneity in the system. Stokes et al. (this volume) also document spatial and temporal patchiness with stable isotopes, but on Conch Reef, a coral ecosystem where hydrography and topography interact to regulate nutrient supply and algal growth.

Forney et al. (this volume) is the only paper in the volume to address fishing impacts directly, a subject of great concern to Paul Dayton. The authors document bycatch of cetaceans in the Hawaii longline fishery and search for regulatory/remediation approaches, reflecting a commitment to translate science into policy inspired by Dayton. Gerrodette (this volume) follows the Dayton lead in challenging paradigms and striving for insight. This paper questions the value of null hypothesis significance testing and demonstrates, with a marine mammal example, how alternative approaches (inference and likelihood methods), that confront the hypothesis with data, can lead to greater insight.

As these papers show, the Dayton legacy is large but the story has no ending; Dayton continues to influence a broad contingent of students, researchers, educators, regulators and legislators. It is a privilege for all of us to know him; we have been inspired in many ways by his unique scientific and human qualities.

There is simply no substitute for actually experiencing Nature: to see, to smell and to listen to the integrated pattern that nature offers an open mind.

Paul K. Dayton, 2010

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Jeff Crooks for the editing of one manuscript in this issue, and Jennifer Gonzalez for editorial assistance. Photographs were contributed by Stacy Kim, Gage Dayton, Linnea Dayton, David Checkley, Simon Thrush, Lisa Levin, Kevin O’Connor, Gordon Robilliard, Robert Paine, Erik Bonsdorf and Julie Barber.