Functional and aesthetic outcomes of abdominal full-thickness skin grafts in paediatric postburn digital and palmar flexion contractures

Abstract

The study aimed to assess the functional and aesthetic outcomes of abdominal full-thickness skin grafts (FTSGs) in paediatric postburn digital and palmar flexion contractures. The digital and palmar functions and aesthetics of 50 children who met the criteria were evaluated at pre-operation, the 3rd- and 12th-month post-operation, respectively. In the evaluation, the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS), total active movement (TAM), and Jebsen–Taylor Hand Function Test (JHFT) were used. The contralateral, unaffected hand served as the criteria for functional recovery. The complications of donor sites were observed, and the take rate of skin grafts was calculated. The VSS scores at the 3rd and 12th months post-operation were lower than those before the operation. The TAM of each finger was improved at the 3rd and 12th months post-operation, compared with that before the operation. There was a significant difference in the time to complete the JHFT between the affected hand and the unaffected at the 3rd month post-operation, but no significant difference between them at the 12th month post-operation. The excellent and good take rate of the skin grafts was 90.00%.No donor site complications were observed. The abdominal FTSGs are effective in repairing paediatric digital and palmar scar contractures, with satisfying functional and aesthetic results, especially in large defects after scar release and resection.

1 INTRODUCTION

Children are prone to hand burns because of their high physical activity levels and poor self-protection awareness. Digital and palmar flexion contractures are common complications of the palmar side of the hand in paediatric burn patients, which affect palmar aesthetics, compromise hand development, and impair hand function. Therefore, it calls for careful attention and meticulous efforts to repair the hand scar for paediatric burn patients.1, 2

Reconstructive surgery is often indicated to improve organ function and life quality. The full-thickness skin grafts (FTSGs) are frequently used to cover the defect surface in the paediatric hand after scar release.3 Chandrasegaram et al.4 showed that, according to their experience in skin grafting for hand burns in children over the past 10 years, the contracture rate of full-thickness skin grafting was lower than that of split-thickness skin grafting. The prospective study has demonstrated the significantly better pliability of FTSGs than split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs).5 The FTSGs retains the full layer of the dermis and maintains a soft texture and good abrasion resistance after transplantation. In the later stages, it is also not easy to contract.

Generally, the donor sites of FTSGs include the abdomen, inguinal region, forearm, posterior ear, and so forth.6-8 In our experience, the most commonly used FTSGs were from the abdomen. The abdomen serves as a good donor site because it has a large area supplying skin grafts with thicker dermis and can be directly sutured after grafting. In addition, the grafted site is often concealed by apparel, and the incidence of complications is often low. In this study, abdominal FTSGs were used to repair paediatric postburn digital and palmar flexion contractures in all operations. We aimed to assess the functional and aesthetic outcomes of abdominal FTSGs in paediatric postburn digital and palmar flexion contractures.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

All paediatric patients with postburn digital and palmar flexion contractures treated with abdominal FTSGs from October 2018 to October 2021 were retrospectively studied. All surgeries were performed by our team, led by Dr. Shen Chuanan. Informed consent was obtained from the patients’ parents. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Review Board of the Department of Burns and Plastic Surgery, Fourth Medical Center of the Chinese PLA General Hospital. Demographic information was collected and analysed, including hand side, age, gender, size of skin graft, aetiology of scar, duration from injury to grafting, length of stay (LOS), surgical technique, the skin graft take rate, complications at the donor site, evaluation results obtained from follow-ups, and so forth.

2.1 Inclusion criteria

- Children aged 1 to 8.

- Unilateral digital and palmar flexion contracture.

- FTSGs used were from the abdomen.

- Follow-up for at least 1 year.

2.2 Surgical technique

The child was given general anaesthesia. After the tourniquet was fixed on the upper arm of the affected limb of the child, the scar of the palm and finger was released and resected while maintaining the integrity of the tendon and aponeurosis. The affected joint is repositioned so that the finger is straightened and fixed in the extended position with a Kirschner wire. The size of the skin defect was measured, and adequate FTSGs were taken from the abdomen. The margins of the cut in the supply area were directly pulled together and sutured. The trimmed FTSGs were transplanted on the hand and sutured with 5 to 0 nylon thread. Pressure dressing was performed to wrap the grafted area with uniform and tight pressure. After the operation, the affected hand was raised and immobilised to promote venous return and prevent graft dislodgement and necrosis. If the grafts were not easily fixed, local tie-over dressing should be applied and removed 10 to 12 days later post-operation. If no unfavourable conditions occurred, the stitches should be removed 14 days post-operation.

After the stitches were removed, a rehabilitation specialist would perform treatment twice a day on the patients' hands to restore their function and guide the families on how to do hand rehabilitation exercises with their children. Upon the healing of the incision, splints were applied on the hands and prophylactic treatment against the scar which would last for 1 year began.

2.3 Outcome measurement

The outcomes were measured in three dimensions: the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS), total active movement (TAM), and Jebsen–Taylor Hand Function Test (JHFT). The time of evaluation for VSS and TAM was pre-operation, the 3rd month and the 12th month post-operation, respectively. The JHFT of the children was examined at the 3rd month and 12th month post-operation. The contralateral, unaffected hand served as the criteria for functional recovery. The patients were evaluated by three doctors independently, the results were recorded, and the mean value was calculated. Besides, the take rate of the skin grafts was also assessed.

2.3.1 VSS

The VSS is a widely used tool for evaluating scar properties. It evaluates scars from four aspects, that is, pigmentation, vascularity, pliability, and height of the scar. The four aspects are scored (on a 0–15 scale), and the total score is calculated. The score is positively correlated with the scar severity.9, 10

2.3.2 TAM

The TAM is used to evaluate how much movement exists at the hand joint and is calculated by subtracting the total extension deficit from the total active flexion of the metacarpophalangeal joint, proximal interphalangeal joint, and distal interphalangeal joint. Each digit was measured as a unit. The calculation of the affected hand is compared with the norm of 260°. The results are classified as: >260°, Normal; 220-259°, Excellent; 180 to 219°, Good; and <180°, Poor.11

2.3.3 JHFT

The JHFT was adopted to evaluate the ability of the hand to perform activities of daily living. It is a standardised test that comprises seven independent subtests evaluating the hand's performance on writing, turning over cards, picking up small objects and placing them in a container, simulated feeding, stacking draughts, picking up large lightweight objects, and picking up large heavy objects.12 Considering some children of younger age were not eligible for the first subtest, only six subtests were conducted. Each task was performed twice, and the average score was taken. In each subtest, a faster time to complete the task means better performance.

2.3.4 Skin grafts take rate

The take rate of the skin grafts was evaluated at the first dressing change and was graded in the following four categories. Excellent: All skin grafts survived. The grafts presented a similar colour to the unaffected skin, had good elasticity, or had some scattered brown spots or light red spots; Good: All skin grafts survived. The colour was light pink, or there were small patchy blood blisters or dark red epidermis were loose. Fair: Almost all the skin grafts survived. Partial necrosis of the epidermis or small pieces of dermis were observed, but regrafting was not necessary. Poor: More than 5% of the grafts were necrotic, which necessitated regrafting and longer dressing changes. The take rate of the skin grafts in the excellent and good groups = (excellent cases + good cases)/total cases × 100%.

2.4 Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed by using the SPSS 25.0 software (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Two-sided P values <.05 were considered statistically significant. Normal distribution and homogeneity of variance of the data were assessed. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or median (range) according to normal distribution and compared by using analysis of independent t-test or Mann–Whitney U tests. Comparisons of categorical variables were conducted using the chi-square test, which was presented as frequencies and percentages.

3 RESULTS

In this 3-year study, 215 children with digital and palmar flexion contractures after burns received surgical treatment in our hospital, 104 of them (48%) received FTSGs, and 50 of the 104 children who received abdominal FTSGs participated in the study. They were 34 boys and 16 girls, with a ratio of 2.1:1. The average age was 34.6 ± 25.0 months (range, 12-96 months). Among the 50 cases, 21 sustained scar contracture deformity in the left hand and 29 in the right hand. The often-involved finger was the middle finger. The average size of the skin graft was (3.4 ± 1.2) × (6.5 ± 2.5)cm2 (ranging from 1 × 2 cm2 to 6.5 × 13 cm2). The causes of the burn injury were flame burn and scald. The median length of time from injury to grafting was 6 months (ranging from 3 to 24 months). The average LOS was 19.4 ± 4.0 days. (Table 1).

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Hand side | |

| Left hand | 21 |

| Right hand | 29 |

| Age, months | 34.6 ± 25.0 |

| Gender, n | |

| Boys | 34 |

| Girls | 16 |

| The average size of skin graft, cm2 | (3.4 ± 1.2) × (6.5 ± 2.5) |

| Aetiology of scar, n | |

| Flame | 9 |

| Scalds | 41 |

| Duration from injury to grafting, months | 6 |

| The average LOS, days | 19.4 ± 4.0 |

3.1 Evaluation results

3.1.1 VSS

The VSS scores of pigmentation, vascularity, pliability and height at the 3rd month post-operation were all improved compared with those before surgery (P values were less than .05) (Table 2). All VSS scores at the 12th month post-operation were significantly different from those before operation (P values were less than .05) (Table 2). In addition, the total VSS scores of patients at the 3rd month and 12th month post-operation were significantly different from those before surgery (P values were all less than .05) (Table 2).

| Pre-operation | The 3rd month post-operation | The 12th month post-operation | P-valuea | P-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pigmentation | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.7 | .000 | .000 |

| Vascularity | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | .000 | .000 |

| Pliability | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | .000 | .000 |

| Height | 2.8 ± 0.9 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | .000 | .000 |

| Total score | 10.3 ± 1.5 | 6.6 ± 1.1 | 3.2 ± 1.1 | .000 | .000 |

- Note: Data expressed as mean ± SD.

- a Pre-operation VS The 3rd month post-operation.

- b Pre-operation versus The 12th month post-operation.

3.1.2 TAM

The difference between preoperative and postoperative TAM of each finger was listed in Table 3. At the 3rd month and 12th month post-operation, the TAM of each finger was significantly different from those before surgery (all P values were less than .05) (Table 3). There existed no significant difference between the TAM of the affected fingers at the 12th month post-operation and the contralateral unaffected fingers (all P values were greater than .05) (Table 3). Among all the patients, two had finger flexion deformity because of scar contracture at the 3rd month post-operation, and the evaluation results of TAM were good. After surgical treatment, the evaluation results of TAM were normal at the 12th month post-operation.

| Ipsilateral | Contralateral | P-valuea | P-valueb | P-valuec | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-operation | the 3rd month post-operation | the 12th month post-operation | |||||

| Thumb | 74 ± 15.9 | 140.5 ± 5.8 | 144 ± 5.0 | 145 ± 5.5 | .000 | .000 | .344 |

| Index finger | 164.7 ± 20.5 | 263.1 ± 31.2 | 273 ± 15.0 | 274 ± 16.1 | .000 | .000 | .749 |

| Middle finger | 159.5 ± 20.4 | 259.7 ± 31.7 | 269.5 ± 16.3 | 272 ± 17.6 | .000 | .000 | .463 |

| Ring finger | 169.3 ± 20.2 | 270.4 ± 28.9 | 279.5 ± 17.2 | 280 ± 16.3 | .000 | .000 | .882 |

| Little finger | 155 ± 24.5 | 258.7 ± 33.6 | 268.9 ± 12.9 | 271 ± 14.6 | .000 | .000 | .448 |

- a Pre-operation VS The 3rd month post-operation.

- b Pre-operation versus The 12th month post-operation.

- c The 12th month post-operation versus Contralateral.

3.1.3 JHFT

As shown in Table 4, the time to finish the JHFT with the affected hand was (7.1 ± 0.9) min at the 3rd month post-operation and (6.4 ± 0.6) min at the 12th month post-operation and was (6.3 ± 0.7) min with the contralateral unaffected hand. The time to complete the JHFT with the affected hand at the 3rd month post-operation was longer than that at the 12th month post-operation and also longer than that of the contralateral unaffected hand (both P values < .05) (Table 4). However, there existed no significant difference in the time to complete the JHFT between the affected hand at the 12th month post-operation and the contralateral unaffected hand (P = .445) (Table 4).

| Ipsilateral | Contralateral | P-valuea | P-valueb | P-valuec | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| the 3rd month post-operation | the 12th month post-operation | |||||

| The mean time | 7.1 ± 0.9 | 6.4 ± 0.6 | 6.3 ± 0.7 | .000 | .000 | .445 |

- a The 3rd month post-operation versus The 12th month post-operation.

- b The 3rd month post-operation versus Contralateral.

- c The 12th month post-operation versus Contralateral.

3.2 Grafts take and complications

The excellent and good take rate of the skin grafts was 90.00%. Three children had fair graft take rates but did not require regrafting. The grafted area healed after 2 weeks of dressing changes. Two children had poor graft take rates, with a necrosis rate of 20% and 10%, respectively, and the grafted area healed after a long period of dressing change. In addition, their hands developed digital flexion contractures again, and they came to our hospital for scar resection and skin regrafting. After follow-up at the 12th month, the grafts were similar to the nearby unaffected skin in both appearance and texture, but occasionally pigmentation could be seen.

Four children developed marginal scar hyperplasia along the surgical incision, but the condition improved after CO2 DOT laser therapy for the scar in the early stage. All donor sites healed well, with no complications, such as infection or incision dehiscence.

3.3 Typical cases

3.3.1 Patient 1

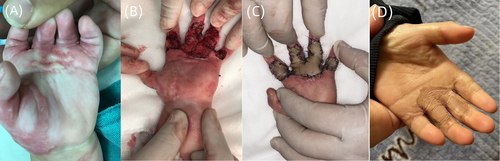

A 1-year-old boy was diagnosed with digital and palmar flexion contractures in the left hand. The cause of the injury was that the left hand was scalded by hot water. During the surgery, we released and resected the scar of the hand and used abdominal FTSGs to cover the defect. The size of the skin graft was about 3 × 4 cm. Hand rehabilitation exercises and prophylactic treatment against scar were performed after the removal of stitches. At present, the function of the left hand was normal, and the appearance was satisfying. (Figure 1).

3.3.2 Patient 2

A 1 year and 6 month-old boy was diagnosed with digital and palmar flexion contractures in the left hand. The cause of the injury was that the left hand was scalded by hot water. During the surgery, we released and resected the scar of the hand and used abdominal FTSGs to cover the defect. The size of the skin graft was about 3 × 5 cm. Hand rehabilitation exercises and prophylactic treatment against scar were performed after the removal of stitches. At present, the function of the left hand was normal, and the appearance was satisfying. (Figure 2).

4 DISCUSSION

Digital and palmar flexion contractures remain a significant problem in children because of scar contractures on the palmar side of the hands after burns.13 Considering the development of hand function in children, FTSGs are the first choice for grafting treatment. The main reason why abdominal FTSGs are preferred is that an intact dermis layer provides maximal elastic properties, which may ensure optimal functional outcome. Compared with STSGs, FTSGs have significantly better pliability and are associated with lower risks of contracture and repeated reconstructive surgeries.14 In addition, they showed a more acceptable skin colour and fewer complications at the donor and recipient sites.7

There is controversy about the optimal graft choice for digital and palmar flexion contractures. Some scholars have demonstrated that FTSGs from routine donor sites, such as the post-auricular, inguinal, and thigh areas are usually associated with poor skin texture, hyperpigmentation, and donor site morbidity.4, 15, 16 The plantar skin could be the preferred choice for repairing skin defects on the volar side of fingers.3 However, we do not share the same opinion. The use of glabrous plantar skin to repair palmar skin defects of the hand and fingers is controversial in many ways.17 The sole of the foot is sensitive, and plantar scars resulting from grafting may cause discomfort for patients. Particularly, it may itch a lot when hypertrophic scars develop. In the treatment of paediatric digital flexion contracture post-burn, the full-thickness plantar skin graft could only be considered in the fingers of children where small defects after excision of scars needed to be coveraged.3 However, when the scars that cause the digital and palmar flexion contractures are resected, the fingers and palms of children will be straightened, resulting in a larger defect that requires more full-thickness skin to achieve coverage, but the amount of full-thickness plantar skin is usually insufficient.

In our opinion, the abdomen should be the preferred donor site for FTSGs. Especially when the defect of the palm and digits is large, the abdomen is a satisfactory donor site for FTSGs. Compared with other donor sites, the skin from the abdomen is more relaxed and can provide more tissue. In our cases, the largest size of the skin graft was 6.5 × 13 cm2. The donor site can be directly sutured with little impact on the abdomen, and the scar on the abdomen can be hidden under apparel.8 In addition, because the donor area is in the abdomen rather than the sole of the foot, children can resume daily activities with an elastic band wrapping the abdomen soon after the operation.

The most important advantage of the abdominal skin is that its dermis is thick, which can satisfy the functional needs of the hand. The palm is a functional organ that is friction-resistant, and the skin grafts required should have thick dermis. The dermis in the abdomen is thicker than that in the thigh.18 The dermis of the skin is the basis for maintaining the toughness, elasticity, and appearance of normal skin. Especially in the joint area, the ductility and elasticity of the dermis affect the range of motion of the joint. Seidenari et al.19 used 20-MHz ultrasound to evaluate skin thickness at different sites in children and demonstrated that the abdominal skin is the thickest. Lo Presti et al.20 found that the thickness of the abdominal skin was thicker than that of the arm and thigh. In the evaluation outcome of hand function in children, the TAM of each affected finger was improved at the 3rd month and 12th month post-operation compared with that before the operation, and there was no obvious difference in the TAM and the time to complete the JHFT between the affected hand at the 12th month post-operation and the contralateral unaffected hand. Therefore, the abdominal skin is suitable to repair the hand defect in children. Our conclusions are consistent with Morandi et al.,7 who compared the outcomes of applying instep STSGs with FTSGs from the lower abdomen in paediatric burn injuries of the palm and determined that the lower abdomen should be the preferred donor site for FTSGs.

For appearance, the VSS scores were improved at the 3rd month and 12th month post-operation compared with those before the operation. Abdominal FTSGs show acceptable colour matching and high patient and parent satisfaction with donor and recipient sites. The skin of the abdominal donor site is relaxed, the tension is small after suture, the scar is not obvious in the later stage, and the site is hidden. There were no donor site complications in our study.

In our experience, several points in the operation are crucial to a good outcome. In the first place, scar is the main reason for the recurrence of contracture deformity in the development of children's hands, so it is necessary to completely remove the scar during the operation to avoid any residual scar. Meanwhile, excision of unaffected muscle and fat should be avoided, so as to affect the function of the hand. Moreover, the surgical incision should be curved or serrated to avoid a straight cut as far as possible so as to avoid scar contracture. In addition, attention should be paid to haemostasis and aseptic procedures to prevent complications such as bleeding and infections. During abdominal skin removal, the skin size should be slightly larger than the defect to achieve complete coverage of the defect after excision. It's preferred to obtain an entire piece of skin graft and avoid splicing. Finally, every effort should be made to ensure a satisfactory take rate. Scar contracture may recur if necrosis occurs.

5 LIMITATION

The study has a few limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, and the grafts were heterogeneous in sizes and anatomical locations, which prevented a more precise evaluation of graft-related motion limitations. Second, while we recognise sensitivity as an important factor in hand function, the study did not discuss the different degrees of sensitivity. Third, a prospective randomised study design would improve the validity of this retrospective study and should be a future study in this field.

6 CONCLUSION

In repairing digital and palmar scar contractures in children after hand burn, abdominal FTSGs are our first choice for large defects after scar release and resection and show satisfying functional and aesthetic results. The abdomen can provide relaxed skin in ample supply. Donor sites can be hidden and have lower complication rates. No relevant scar hypertrophy was observed in the study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.