Dental caries and associated factors in 7-, 12- and 15-year-old schoolchildren in the canton of Basel-Landschaft, Switzerland: Changes in caries experience from 1992 to 2021

Abstract

Background

Epidemiological surveys in schoolchildren are used to assess the current status of oral health.

Aim

To investigate the changes in caries experience among schoolchildren in the canton of Basel-Landschaft, Switzerland, over a period of three decades. Secondary objectives were to evaluate the impact of various personal and demographic factors such as age group, place of residence or dental hygiene awareness on caries prevalence as well as the history of orthodontic treatment in the year 2021.

Design

A random sampling of school classes from first, sixth and ninth grades, that is schoolchildren aged 7, 12 and 15 years, was performed. Children's dmft and DMFT scores were determined according to the WHO methodology while information on oral hygiene habits and dental prophylaxis awareness was collected by means of a questionnaire directed to the legal guardians of the children. Individual logistic regressions were performed to identify possible influencing factors for caries.

Results

A total of 1357 schoolchildren could be included in the study. In the year 2021, the youngest age group had an average of 0.68 primary teeth that needed treatment, whereas the 12- and 15-year-olds each had approximately 0.3 permanent teeth requiring treatment. While these numbers remained constant over the examination period of three decades, most of the other caries indices improved. Younger children (p = .001) and children with a migrant background (p < .001) were found to be risk groups. Orthodontic treatment was more frequent in females, schoolchildren of Swiss nationality and children attending higher secondary schools at ninth grade.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that even in a country with a low prevalence of caries experience, untreated carious lesions remain a problem as their prevalence remained unchanged over the examination period of three decades.

Why this paper is important to paediatric dentists

- This study demonstrated that even in countries such as Switzerland with a low prevalence of caries experience, untreated carious lesions remain a problem as the number remained constant over a period of three decades.

- Schoolchildren with a migrant background, low scores in a self-reported dental hygiene awareness questionnaire and lower educational achievement levels were shown to be at risk for both caries experience and active caries, indicating that these risk groups have not yet been fully addressed by existing prophylaxis measures.

- Differences exist based on sex, nationality and the level of school achievement as to which children receive orthodontic treatment.

1 INTRODUCTION

Despite considerable efforts, caries remains a highly prevalent oral disease in children and adolescents worldwide.1, 2 Caries experience varies considerably among countries, with declining rates reported from countries with a higher economic and social standard, whereas caries prevalence continues to increase in low- and middle-income countries.3, 4 Potential influencing factors discussed for these geographical differences in caries prevalence in children include a migrant background, socio-economic status, lifestyle factors, parental caring behaviours and birth order.5, 6

Epidemiological surveys can help to assess the current status of oral health in a population and show whether changes have occurred, thus orientating the responsible authorities to the need for future action. This is of importance as dental caries can be controlled, when prevented or detected early and treated adequately, resulting in an improved quality of life and lower economic healthcare-related costs.

Switzerland has a long tradition of oral epidemiological surveys of children.7 Studies based on the World Health Organization (WHO) methodology are often conducted on schoolchildren, as most children in Switzerland attend public schools and are therefore easy to recruit.7, 8 In the canton of Basel-Landschaft, a region in the northern-western part of Switzerland, dental health examinations of schoolchildren must be, based on regional law, performed regularly.7, 9 Therefore, representative data on caries experience and prevalence in children aged 7, 12 and 15 years exist since 1992.7 During the first 10 years, a decline in caries prevalence could be observed in all age groups, whereas in 2011, this decline seemed to have levelled off.7

The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of dental caries among schoolchildren in the canton of Basel-Landschaft, Switzerland, in 2021 and to describe possible changes in prevalence over a period of three decades. Secondary objectives were to evaluate the impact of various personal and demographic factors such as age group, place of residence or dental hygiene awareness on caries prevalence as well as the history of orthodontic treatment in the year 2021.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Ethics approval

A study protocol was submitted to the ethical committee Northwest and Central Switzerland (EKNZ 2021-00107). The study was exempt from formal approval as the planned oral health surveys were, based on regional law, considered mandatory and must be carried out regularly.9 The legal guardians of the children were informed that by not filling in the respective questionnaire, the data would not be further used for research purposes.

2.2 Sampling procedure and participants

The sampling procedure and the selection of participants have been described in detail by Grieshaber et al.10 In order to examine comparable age groups and sample sizes as in previous studies conducted in the canton of Basel-Landschaft, that is children aged 7, 12 and 15 years, a random sampling of school classes from first, sixth and ninth grades was performed.7, 10 After 2 years at kindergarten, children in the canton of Basel-Landschaft first spend 6 years at a primary school before switching to a secondary school for the last 3 years. The secondary school has three different sections where children are assigned based on their school performance, that is Section A (general requirements), Section E (extended requirements) and Section P (baccalaureate-level requirements). Accordingly, the study population consisted of first-grade schoolchildren in their first year of primary school, sixth-grade schoolchildren attending the last year of primary school and ninth-grade schoolchildren in their final year of compulsory education (Section A, E or P).

Prior to the dental examination, the legal guardians of the selected schoolchildren received information about the purpose and procedures of the examinations. Additionally, they were asked to fill in a questionnaire to complete the basic demographic data obtained by the Cantonal Statistical Office, Basel-Landschaft, and to collect information on oral hygiene habits and attitudes towards dental prophylaxis.

2.3 Dental examinations

Dental examinations were carried out by three teams, each consisting of an experienced paediatric dentist and a dental assistant. Dental examinations were performed according to the principles recommended by the WHO for clinical oral health surveys.8 In particular, all examinations were conducted in schoolrooms under artificial light (high-performance LED headlamps). The examinations were always announced in advance, so the children could brush their teeth before class. Excess saliva was, if necessary, removed with a cotton swab by the dentist before the dental examination.

To confirm the diagnosis of caries, a sickle probe and a plane mouth mirror were used. Criteria for diagnosing the dentition status and the coding used were according to the guidelines of the WHO.8 Molar incisor hypomineralisation (MIH) was diagnosed as described by Grieshaber et al.10 and is based on the evaluation system described by Steffen et al.11

2.4 Data collection

All clinical data as well as the information from the questionnaire were entered on-site in a Microsoft Access-based data entry program (Microsoft Corporation).

DMFT and dmft values were calculated according to the WHO methodology.8 For sixth and ninth graders, that is 12- and 15-year-old schoolchildren, only the caries experience in the permanent dentition (DMFT) was calculated. For populations with both, individuals with considerably higher DMFT values and caries-free individuals, the Significant Caries Index (SiC; average dmft or DMFT in the upper tertile, respectively) is a suitable indicator as it records the individuals with the highest DMFT values.12 Therefore, the SiC was calculated for all age groups.

MIH values per child were presented as a dichotomous variable, with ‘1’ representing the presence of MIH (yes) and ‘0’ representing the absence of MIH (no).10

Age was calculated as the difference between the date of the dental examination and the date of birth.

The classification of the children's places of residence was based on the regional typology published by the Federal Statistical Office13-15 and corresponds to the procedure described by Grieshaber et al.10 In brief, the algorithm used for the classification into rural, intermediate or urban region includes both morphological and functional criteria such as the permanent residual population or jobs/employed persons in the respective region.

The level of dental hygiene awareness was assessed by combining answers to oral hygiene questions from the questionnaire. For each positive response, a score of 1 was given. Specifically, answers to the following questions were included: date of last dental visit (‘1’, if the date was less than 1 year ago, and ‘0’, if more than 1 year or question was left blank), the use of toothpaste (‘1’, if toothpaste is used, and ‘0’, if not or question was left blank), the use of an additional tooth-cleaning aid such as mouth wash, fluoride gel or dental floss (‘1’, if at least one additional tooth-cleaning aid is used, and ‘0’, if none of these products is used), conclusion of dental insurance (‘1’, if a dental insurance had been taken out, and ‘0’, if not or question was left blank), fluoridation of the child's teeth in the dental practice during a visit (‘1’ if the parents allow the fluoridation, and ‘0’, if not or question was left blank). After adding up the individual scores, the children's dental hygiene awareness level was classified into high (score of 4–5), medium (score of 2–3) and low (score of 0–1).

The percentage of 12- and 15-year-old children who have undergone or are currently undergoing orthodontic treatment was calculated by analysing the responses to the corresponding question in the questionnaire.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: complete basic demographic data as obtained from the Cantonal Statistical Office, Basel-Landschaft, questionnaire and the results from the clinical examination were present. Children with incomplete data, either from the clinical examination and/or basic demographic data and/or questionnaire, were excluded from the study. Prior to the statistical analysis, all data were anonymised.

2.5 Inter-rater reliability

Prior to the start of the study, the reliability of the clinical examinations between pairs of examiners was assessed by comparing their dmft and DMFT findings in schoolchildren from two school classes (first and sixth grades, respectively). Cohen's kappa values for the three examiners’ caries detection inter-rater reliability ratings ranged from 0.67 to 0.72. The corresponding values for MIH ranged from 0.72 to 0.89 and have been reported earlier.10

2.6 Statistical analysis

To identify possible influencing factors for caries experience/active caries such as age, sex, nationality, place of residence, MIH, dental hygiene awareness and the school level at ninth grade, individual logistic regressions were performed. Likewise, to identify possible associated factors for prevalence of orthodontic treatment such as age, sex, nationality, place of residence, caries experience and the school level at ninth grade, individual logistic regressions were performed. For significant categorical variables, post hoc pairwise comparisons were also performed with the Bonferroni adjustment. All of the tests performed were two-tailed tests with a .05 significance level.

The analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 28 (IBM Corp.).

3 RESULTS

In total, 1822 schoolchildren were selected to participate in this study. Four hundred and sixty-five children (25.5%), however, were either absent from class on the day of the dental examination or did not hand in the questionnaire. The rest (1357; 74.5%) were included in this study. Approximately three-quarters of the children examined were Swiss, and nearly equal numbers of male and female children were observed in the study population which were similar for all age categories. The detailed characteristics of the study population analysed in 2021 are shown in Table 1.

| N | Age (years) (min–max) | Sex | Nationality | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Swiss | Foreign | |||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| All children | 1357 | 11.5 (6.1–17.9) | 702 | 51.7 | 655 | 48.3 | 1012 | 74.6 | 345 | 25.4 |

| 7-year-olds (First grade) | 510 | 7.4 (6.1–8.6) | 253 | 49.6 | 257 | 50.4 | 392 | 76.9 | 118 | 23.1 |

| 12-year-olds (Sixth grade) | 472 | 12.6 (11.6–14.0) | 269 | 57.0 | 203 | 43.0 | 357 | 75.6 | 115 | 24.4 |

| 15-year-olds (Ninth grade) | 375 | 15.7 (14.4–17.9) | 180 | 48.0 | 195 | 52.0 | 263 | 70.1 | 112 | 29.9 |

- Note: Shown are sample size, age, sex, and nationality for all participants and the three age categories.

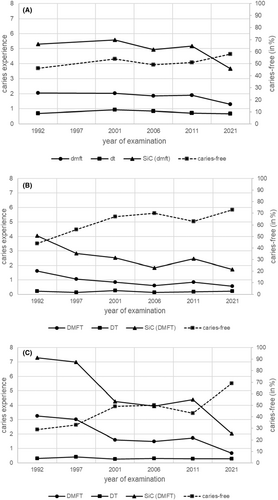

Table 2 shows the caries experience among the schoolchildren. In the year 2021, the youngest age group, that is the 7-year-olds, had an average of 0.68 primary teeth that needed treatment, whereas the two older study groups each had approximately 0.3 permanent teeth requiring treatment. About 60% of the children had a caries-free primary dentition, and about 70% had a caries-free permanent dentition. During a period of three decades, these caries indices either remained constant or even improved (Figure 1). In particular, the number of schoolchildren with a caries-free permanent dentition increased from 44% in the year 1992 to 73% in the year 2021 for 12-year-olds and from 29% in the year 1992 to 69% in the year 2021 for 15-year-olds.

| Primary dentition | Permanent dentition | Significant Caries Index | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dmft | dt | Caries-free (%) | DMFT | DT | Caries-free (%) | SiC dmft | SiC DMFT | |

| 7-year-olds | 1.31 | 0.68 | 58.4 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 93.3 | 3.67 | — |

| 12-year-olds | — | — | — | 0.57 | 0.29 | 72.7 | — |

1.72 (all) 1.55 (11–13 years old) |

| 15-year-olds | — | — | — | 0.68 | 0.28 | 69.1 | — | 2.04 |

- Note: Shown are the mean dmft/DMFT values, mean dt/DT values, the percentage of caries-free children (dmft = 0, respectively, DMFT = 0) and the Significant Caries Index (SiC) in the primary (mean dmft upper tertile) and permanent dentition (mean DMFT upper tertile) for the three age categories.

Both the presence or absence of caries and of active carious lesions were not statistically significantly different for sex or the place of residence in the year 2021 (Table 3). Statistically significant differences, however, were found for the other socio-economic and confounding factors analysed. Specifically, younger children and children with a migrant background had a higher total caries experience and more active caries. Statistically significant associations were found between caries experience and the presence of MIH or the level of secondary school attended in ninth grade, as well as active carious lesions and self-described dental hygiene awareness (Table 3). Post hoc pairwise comparisons showed that children in the medium dental hygiene awareness group had a significantly higher caries prevalence (41.1%) than those in the high dental hygiene awareness group (34.1%). Similarly, children in the medium dental hygiene awareness group had a significantly higher active caries prevalence (29.0%) than those in the high dental hygiene awareness group (21.1%). When analysing the influence of the level at ninth grade using post hoc testing, children attending level P had a significantly lower caries prevalence (18.8%) than children attending level A (44.0%) and level E (33.8%) group, respectively. Likewise, children attending level P at ninth grade had a significantly lower caries prevalence (8.3%) than those attending level A (21.0%).

| All | Caries experience | p value | Active caries | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (dmft + DMFT = 0) | Yes (dmft + DMFT > 0) | No (dt + DT = 0) | Yes (dt + DT > 0) | ||||

| All | 1357 | 850 (62.2%) | 507 (37.4%) | n.a. | 1022 (75.3%) | 335 (24.7%) | n.a. |

| Age group | |||||||

| 7-year-olds | 510 (37.6%) | 290 (56.9%) | 220 (43.1%) | .001* | 345 (67.6%) | 165 (32.4%) | <.001* |

| 12-year-olds | 472 (34.8%) | 302 (64.0%) | 170 (36.0%) | 360 (76.3%) | 112 (23.7%) | ||

| 15-year-olds | 375 (27.6%) | 258 (68.8%) | 117 (31.2%) | 317 (84.5%) | 58 (15.5%) | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 702 (51.7%) | 429 (61.1%) | 273 (38.9%) | 0229 | 521 (74.2%) | 181 (25.8%) | .332 |

| Female | 655 (48.3%) | 421 (64.3%) | 234 (35.7%) | 501 (76.5%) | 154 (23.5%) | ||

| Nationality | |||||||

| Swiss | 1012 (74.6%) | 688 (68%) | 324 (32%) | <.001* | 805 (79.5%) | 207 (20.5%) | <.001* |

| Foreign | 345 (25.4%) | 162 (47%) | 183 (53%) | 217 (62.9%) | 128 (37.1%) | ||

| Regional typology | |||||||

| Urban | 890 (65.6%) | 540 (60.7%) | 350 (39.3%) | .130 | 655 (73.6%) | 235 (26.4%) | .110 |

| Intermediate | 281 (20.7%) | 187 (66.5%) | 94 (33.5%) | 224 (79.7%) | 57 (20.3%) | ||

| Rural | 186 (13.7%) | 123 (66.1%) | 63 (33.9%) | 143 (76.9%) | 43 (23.1%) | ||

| MIH | |||||||

| No | 1164 (85.6%) | 747 (64.2%) | 417 (35.8%) | .004* | 888 (76.3%) | 276 (23.7%) | .041* |

| Yes | 193 (14.2%) | 103 (53.4%) | 90 (46.6%) | 134 (69.4%) | 59 (30.6%) | ||

| Dental hygiene awareness | |||||||

| Low (0–1) | 88 (6.5%) | 54 (61.4%) | 34 (38.6%) | .039* | 66 (75.0%) | 22 (25.0%) | .005* |

| Medium (2–3) | 572 (42.1%) | 337 (58.9%) | 235 (41.1%) | 406 (71.0%) | 166 (29.0%) | ||

| High (4–5) | 697 (51.4%) | 459 (65.9%) | 238 (34.1%) | 550 (78.9%) | 147 (21.1%) | ||

| Level at ninth grade | |||||||

| Level A | 100 (26.7%) | 56 (56.0%) | 44 (44.0%) | <.001* | 79 (79.0%) | 21 (21.0%) | .018* |

| Level E | 142 (37.9%) | 94 (66.2%) | 48 (33.8%) | 116 (81.7%) | 26 (18.3%) | ||

| Level P | 133 (35.5%) | 108 (81.2%) | 25 (18.8%) | 122 (91.7%) | 11 (8.3%) | ||

- Note: Shown are total numbers and percentages (in brackets) for schoolchildren without or with caries experience (dmft + DMFT = 0 or dmft + DMFT > 0, respectively) and without or with active carious lesions (dt + DT = 0 or dt + DT > 0, respectively). A—general requirements, E—extended requirements and P—baccalaureate-level requirements at ninth grade for 15-year-old schoolchildren in secondary school.

- *p value is significant at <.05.

- Abbreviation: MIH, molar incisor hypomineralisation.

Furthermore, females, schoolchildren of Swiss nationality and children attending higher secondary schools at ninth grade were significantly more likely to have undergone or to be currently undergoing orthodontic treatment, while no differences were found for age group, place of residence or caries experience (Table 4). It was observed from the post hoc testing that schoolchildren attending level A at ninth grade had a significantly lower proportion of undergoing orthodontic treatment (45.0%) than that (63.2%) of level P group.

| Percentage of children with orthodontic treatment | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| All 12- and 15-year-olds (n = 847) | 53.4 (n = 452) | n.a. |

| Age group | ||

| 12-year-olds (n = 472) | 50.8 (n = 240) | .100 |

| 15-year-olds (n = 375) | 56.5 (n = 56.5) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male (n = 449) | 47.7 (n = 214) | <.001* |

| Female (n = 398) | 59.8 (n = 238) | |

| Nationality | ||

| Swiss (n = 620) | 57.3 (n = 355) | <.001* |

| Foreign (n = 227) | 42.7 (n = 97) | |

| Regional typology | ||

| Urban (n = 522) | 54.2 (n = 283) | .527 |

| Intermediate (n = 209) | 50.2 (n = 105) | |

| Rural (n = 116) | 55.2 (n = 64) | |

| Caries experience | ||

| No (dmft + DMFT = 0) | 55.4 (n = 310) | .105 |

| Yes (dmft + DMFT >0) | 49.5 (n = 142) | |

| Level at ninth grade | ||

| Level A | 45.0 (n = 45) | .019* |

| Level E | 58.5 (n = 83) | |

| Level P | 63.2 (n = 84) | |

- Note: Shown are the percentages and total number (in parentheses) of children currently undergoing or who underwent orthodontic treatment in the past. A = general requirements, E = extended requirements and P = baccalaureate-level requirements at ninth grade for 15-year-old schoolchildren in secondary school.

- * p-Value is significant at <.05.

4 DISCUSSION

This study presents an overview of the caries experience among schoolchildren in the canton of Basel-Landschaft, Switzerland, over three decades. Particularly in the age groups of the 12- and 15-year-old children, most dental caries indices have improved over this time period. Ten years ago, the steady decline in dmft and DMFT appeared to level off7; per current data, however, the rate of caries experience did not increase again in 2021.

Globally, untreated carious lesions are a major health concern, with untreated caries in primary teeth being the most prevalent disease for children aged 0–14 years and untreated caries in permanent teeth being the predominant health condition in the year 2019.16 Its prevalence and incidence remain static. Additionally, caries is not evenly distributed across regions and countries; therefore, simple, cost-effective and sustainable interventions are needed that are adapted to the particular region.2, 4, 17 Switzerland is considered to be a country with a low prevalence of untreated carious lesions.16 Nevertheless, the average number of teeth with untreated carious lesions either in primary or in permanent teeth, that is dt and DT, respectively, did not decrease but remained constant over time for all three age groups examined. This is despite the fact that in the canton of Basel-Landschaft, as in the whole of Switzerland, comprehensive preventive measures such as regular toothbrushing instructions in schools and an annual dental check-up are offered free of charge to all schoolchildren.

In the present study, nationality was shown to be a risk factor as mean dmft/DMFT and dt/DT values were significantly higher in schoolchildren with a migrant background. This association has already been reported in a previous study in Switzerland.7 Socio-economic factors such as education or income are known to play an important role in explaining differences in dental caries.4, 18 These factors have not been analysed in detail in the present study as there are ethical boundaries in Switzerland to access certain socio-economic factors such as employment, education or income in each family.5 Therefore, the influence of education could be analysed only in 15-year-olds as they attend three different sections based on their school performance. Schoolchildren visiting a school with baccalaureate-level requirements had the lowest caries prevalence of all ninth graders, indicating an influence of school achievement on caries.

The correlation between MIH and caries is currently still discussed, as there are studies that show a positive correlation and others that show no significant correlation.19 Also in our study, a positive correlation could be noticed. It has been argued that, especially in severe MIH-associated hypersensitivity, children will maintain insufficient oral care, which may lead to more carious lesions.19 In the present study, the severity of MIH was not analysed. Therefore, more detailed studies are needed to identify possible interactions between these two diseases.

Successful caries prevention requires a multilevel intervention approach that includes both general public oral health measures and individual person-centred dental care. Population-based caries prevention programmes were initiated as early as the 1960s in Switzerland and thus have a long tradition. Accordingly, a decline in dental caries could be observed initially.7 As social, economic and environmental factors, however, also influence the disease, a more personalised approach is required to identify children in need of dental interventions, ideally as early as possible. One of the approaches discussed is that dental services should be more integrated into the overall healthcare system.20, 21 Furthermore, it has been shown that the caries status of the first-born child can be used as a predictor for caries in younger siblings of the same family. This allows families in need of dental treatment to be identified, ensuring that available resources are utilised carefully and in a targeted manner.5

A known risk factor for dental caries is the consumption of sugar. In 2015, the WHO published a guideline with the recommendations to limit the intake of free sugars in adults and children to less than 10% of total energy intake.22 One possibility is the taxing of sugar-sweetened beverages. It has been calculated that such a taxation could reduce the number of caries occurrence in children by 2.7%–2.9% over a 10-year period.23 In Switzerland, only 44% of women and 45% of men had a free sugar intake below the recommended 10% of total energy intake, indicating a low adherence to the recommendations.24 So far, there have been no corresponding data on Swiss children. As the negative health effects of dental caries, however, are cumulative, a reduction in free sugar intake in childhood may be of significance in adulthood.

The legal guardians of the schoolchildren were asked to complete a questionnaire that addressed, among other things, various aspects of dental hygiene, resulting in an assessment of dental hygiene awareness. Dental hygiene awareness is another factor that is determined and shaped in children and adolescents mainly by the family environment, where not only family traditions but also socio-economic status and education play an important role. Indeed, respondents with high dental hygiene awareness levels were found to have statistically significantly lower caries experience and fewer active carious lesions.

In this context, it should be noted that questionnaires are prone to subjectivity and therefore present a limitation in this study. Only children with a complete data set, that is with both the clinical examination and a filled-in questionnaire, were included in the study. It was not possible to follow up on the missing schoolchildren due to the COVID-19 pandemic during the dental examination period, which has led to some restrictions in the clinical evaluation process. Moreover, it cannot be excluded that there were also children with increased caries activity among the dropouts and that this specific population group was thus not included in the study. Additionally, the dental examinations were performed as recommended by the WHO for clinical oral health surveys, which do not include bitewings or other X-ray examinations.8 Clinical analysis alone cannot detect approximal caries. Therefore, the actual caries activity might have been underestimated.

Statistically significantly more female than male schoolchildren received orthodontic treatment. Such sex-specific differences have been noted in previous studies.25-27 Differences in attitudes towards orthodontic treatment were also attributed to age, socio-economic status and geographical context.25 While no regional differences were found, statistically significant differences were also observed in the present study for socio-economic parameters such as nationality and the level of school achievement of the respective child.

Orthodontic therapy presents potential risks including periodontal damage, pain, root resorption, tooth devitalisation, temporomandibular disorder, caries, speech problems and enamel damage, with white spot lesions being one of the most common side effects.28 In the present study, no differences were found between children with or without caries experience and orthodontic treatment. On the one hand, this may be due to the fact that only carious lesions at the D3 or D4 level were recorded in this study. Initial lesions, that is D1 and D2 lesions, can be generally managed using preventive measures such as the application of fluorides.8, 28, 29 On the other hand, orthodontic treatment in Switzerland should start only when the patient is caries-free and oral hygiene has reached a good level.30

In conclusion, the caries experience of schoolchildren in the canton of Basel-Landschaft, Switzerland, has not increased since the last survey over a decade ago. However, the average number of teeth with untreated carious lesions either in primary or in permanent teeth, that is dt and DT, respectively, has not improved but remained constant over three decades for all three age groups examined. Risk factors for an increased level of caries activity were found to include migrant status and self-declared dental hygiene awareness.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Andreina Grieshaber, Tuomas Waltimo, Michael Marc Bornstein and Eva Maria Kulik conceived the idea and designed the study; Andreina Grieshaber and Asin Ahmad Haschemi collected the data; Eva Maria Kulik analysed the data; Andreina Grieshaber, Michael Marc Bornstein and Eva Maria Kulik interpreted the data and drafted the initial manuscript. All the authors revised and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Ms. Kar Yan Li, Central Research Laboratory, Faculty of Dentistry, The University of Hong Kong, for her valuable assistance regarding the statistical analysis. The authors would also like to thank Ms. Caroline Baumann, Ms. Judith Erb, Ms. Christl Hösch, Ms. Behare Limani, Ms. Patricia Maass, Dr. Ludmila Strickler, Ms. Daniela Senapo, Dr. Richard Steffen and Mr. Tobias Wiederkehr for their valuable administrative and scientific support. Open access funding provided by Universitat Basel.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The study was financially supported by the canton of Basel-Landschaft, Switzerland. The funders have no influence on the study design, data collection and analysis, and manuscript preparation.

ETHICS STATEMENT

A study protocol was submitted to the Ethical Committee Northwest and Central Switzerland (EKNZ 2021-00107), but the study was exempt from formal approval as the planned oral health check-ups were considered mandatory.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.