Being a nurse during an earthquake that affected ten provinces: A qualitative study on experiences and expectations

Abstract

Aim

This study was conducted to determine the professional experiences and future expectations of nurses working in the most damaged areas during the first two weeks of the 2023 Turkey earthquake.

Background

The increase in the frequency and severity of disasters in recent years has strongly shown that nurses must be prepared to respond to all disasters. To prepare for disasters that require a multifaceted approach, the experiences of nurses serving in disasters should not be ignored.

Methods

A hermeneutic phenomenological approach was used in this research. The study included 18 nurses who worked in the first two weeks of the disaster. Data were collected through semistructured in-depth interviews between April and May 2023.

Results

Four themes were identified from the analysis of the data: (1) personal challenges, (2) organizational challenges, (3) nursing during the disaster, and (4) expectations.

Conclusions

The results showed that nurses needed psychosocial support intervention skills in disasters and that their psychological preparation and knowledge levels for disasters were insufficient. In addition, the study revealed that organizational preparation was inadequate and that all these factors affected nursing care.

Implications for nursing and health policy

The knowledge and skills that nurses need for professional disaster management can be provided by updating undergraduate education, in-service training procedures, and related policies. Considering that ideal disaster management is possible with a multidisciplinary team, it is recommended that national disaster policies be reviewed.

INTRODUCTION

Disasters are generally sudden events that exceed local response capacity, require national or international intervention, and cause great damage and loss of life (Guha-Sapir et al., 2017). They have always threatened human beings and are globally increasing in number and severity (Shen et al., 2018; Tin et al., 2024). Two consecutive earthquakes with magnitudes of 7.7 and 7.6 hit 10 provinces in Turkey on February 6, 2023.

Nurses make up one of the most important human resources for society to cope with disasters (Aykan et al., 2022). They are involved in important aspects on disaster management including making health assessments at all stages of disaster management, determining priorities, achieving cooperation, managing care, and preparing for extraordinary conditions (Kalanlar & Gülümser, 2015). Nurses’ competency in disaster response is very important in reducing the negative consequences on the health of people affected by disasters (Brewer et al., 2020). They must be prepared for disasters, perform their responsibilities competently during a disaster, and respond quickly (Koçak & Serin, 2023; Songwathana & Timalsina, 2021). Nurses' competency in disaster management creates a strong sense of readiness to help disaster victims (Emaliyawati et al., 2021; Songwathana & Timalsina, 2021) and reduces their anxiety and hesitations (Setyawati et al., 2020). Competent nurses can provide quality care and psychological support to the population affected, increase the trust of the community in healthcare providers, and reduce mortality and complications following disasters (Chegini et al., 2022). In addition, they can understand disaster plans, achieve communication at the disaster site, ensure decontamination and safety, solve ethical problems, and manage cases competently (Al Thobaity et al., 2017).

As the frequency and severity of disasters have increased in recent years, it has become even more important for nurses to be ready to deal with these occurrences (Chegini et al., 2022). Nurses, especially in developing countries, are not sufficiently prepared to deal with disasters and do not trust themselves in disaster management (Labrague et al., 2018; Songwathana & Timalsina, 2021). The reasons for these adversities are related to education, training, and institutional and organizational factors (Songwathana & Timalsina, 2021). Another factor that increases disaster response preparedness is experience. Having disaster-related experience has many benefits (Becker et al., 2017). Therefore, the experiences of nurses who have worked in disasters are a unique source of information in guiding preparedness initiatives. Although there are studies on the examination of the difficulties experienced by nurses and their experiences during earthquakes (Dehkordi et al., 2021; Moradi et al., 2020; Rezaei et al., 2020), literature on the subject is still limited (Erdem et al., 2023). Existing studies indicate that nurses have varying characteristics and situations, such as their “disaster preparedness level,” “disaster-related training status,” “institution where they work,” “disaster experiences,” “service in disasters,” “experience as an earthquake victim,” “loss of life and property in earthquakes,” “the days on which the disaster occurred,” and “the country where the disaster occurred and its capabilities.” These differences may affect the nursing services provided in disaster areas and the experiences gained. For these reasons, more evidence on the subject is needed. Specifically, the evidence from this study, which includes earthquake-affected nurses and covers the most chaotic days of the earthquake, will support the development of advanced nursing practices targeted in the ICN (2019) report. This study was conducted to determine the professional experiences and future expectations of nurses working in the most severely damaged areas during the first two weeks of the 2023 Turkey earthquake.

METHODS

Design

This study was conducted as qualitative research based on Heidegger's phenomenological hermeneutic scientific approach to reveal the experiences of nurses who provided care to earthquake victims in the three provinces (Adıyaman, Hatay, and Kahramanmaraş) where most loss of life and property occurred in the earthquake that affected 10 provinces of Turkey on February 6, 2023, and the meanings hidden in their experiences. The phenomenological method provides an in-depth perspective on participants’ experiences (Giorgi, 1997).

Sample and setting

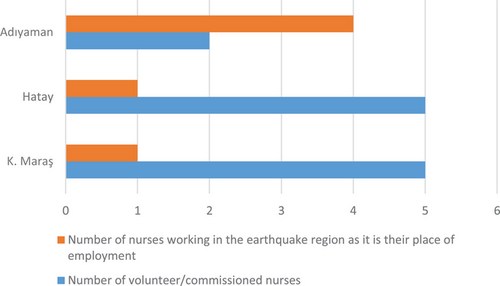

The participants included 18 nurses who worked or volunteerd in the earthquake zone in Turkey. Participants were selected using the snowball sampling method, one of the purposive sampling methods. Snowball sampling enables obtaining new information-laden situations by asking who else can be interviewed (Patton, 2014). The first participant was a nurse who worked in the province where the study was conducted, was known to the researchers, and worked in Kahramanmaraş, which was the epicenter of the earthquake. At the end of each interview, each nurse was asked, “Who would you recommend to be interviewed?” so that other participants could be reached. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Working in the provinces where AFAD reported the highest loss of life and property in the earthquake (Kahramanmaraş, Hatay, and Adıyaman); (2) Working in the field within the first two weeks after the earthquake (Figure 1).

Data collection tools

Study data were collected between April and May 2023 by using a descriptive information form and a semistructured interview guide developed by the researchers after a literature review (Table 1) (Akpinar & Ceran, 2020; Şimşek & Gündüz, 2021). The researchers contacted potential participants by phone to inform them about the study. The nurses were interviewed over the telephone by the primary researcher (EGE) at a mutually agreed time. At the end of each interview, the researcher asked them to confirm the accuracy of the interview recordings. The interviews were 20–45 minutes long and were audio recorded. The researcher took notes during the interviews. The participants experienced intense emotions, and the interviews were sometimes interrupted for short periods. In these cases, the researcher continued the interview by noting the last spoken points to continue the interview from where it stopped and to facilitate the flow of the interview. In qualitative studies, the sample size is not predetermined, and interviews continue until no new information or opinions emerge, or until data saturation is reached. Therefore, the determination of the sample size was based on observing data saturation, which occurs when the responses from participants begin to repeat a similar pattern (Fusch & Ness, 2015). At this point, data collection was stopped.

| Questions |

|---|

| 1. What are the difficulties you experienced as a nurse working in the disaster area? What did you do/what methods did you follow to cope with these difficulties? |

| 2. How did you feel while caring for an earthquake victim in the disaster area? What did you do/what methods did you follow to cope with the emotions you experienced? |

| 3. What knowledge and skills did you realize you needed while working in the disaster area? What did you do/what methods did you follow to cope with these difficulties? |

| 4. What did nursing during the disaster teach you? |

| 5. What did the concept of “nursing care” mean to you when you were caring for earthquake victims? Can you share your feelings and thoughts? |

| 6. As a nurse who worked in the disaster area, what are your expectations regarding disasters? |

Data analysis

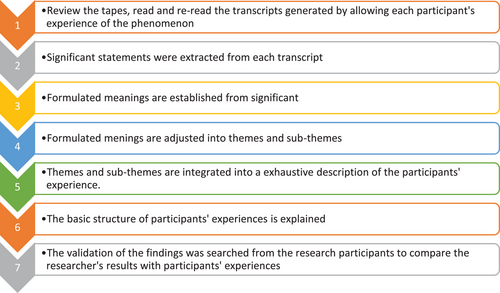

Data were analyzed using Colaizzi's (1978) seven-step analysis (Figure 2). First, the most meaningful sentences describing the main study phenomenon were extracted by both researchers, and the statements were grouped into various codes and categories. Then, subthemes and main themes were created. For each theme, an in-depth explanation was presented and meaning was formulated. The reliability of the themes and their explanations and the accuracy of the analysis process were determined by researchers (EGE and ŞŞK) who had education in qualitative research.

Ethical consideration

Before the study was initiated, approval (decision no: 2023.03.30) of the Ethics Committee of a university was obtained. Nurses were informed that participation in the study was voluntary and that they could quit at any time. Participant approval was obtained before the interviews were audio recorded. To preserve anonymity, hard copies of interview transcripts were assigned serial numbers and kept in secure cabinets accessible only to the researcher. All digital data were kept on a password-protected computer accessible only to EGE. Participants were encouraged to seek professional psychological support as they were affected by the disaster.

Trustworthiness

To increase the precision of the results and the reliability of the research, the study was evaluated for confirmability, reliability, credibility, and transferability criteria (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Reliability was achieved by independently reading and categorizing interview transcripts. To increase the reliability of the data, its originality was maintained. Additionally, after the transcripts were created, the participants were contacted by phone and asked if they wanted to add/remove anything from the interviews. The approval of each participant was obtained when creating themes and subthemes. To ensure reliability, all translated transcripts were examined and the feedback of two experts experienced in qualitative research was received (academics working at different universities, independent of the research). To ensure confirmability, the original interviews were adhered to and the nurses' responses were presented directly. Additionally, the original materials of the study were safely preserved for future verification. The findings of this study can be used and adapted to nurses in different societies with similar characteristics.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

A total of 18 nurses participated in this study. Their mean age was 31.33 ± 6.67 years, 61.1% of them were female, and 77.8% were university graduates. Fifty percent had worked voluntarily in the earthquake-stricken region and 83.3% had provided outpatient diagnosis and treatment services (Table 2). All participants had experienced the second major earthquake in the region, and 88.9% of them had not worked in a disaster area before (Table 3). Four themes were elicited from nurses’ statements: (a) personal difficulties, (b) organizational difficulties, (c) nursing during the disaster process, and (d) expectations (Table 4).

| Descriptive characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age groups | ||

| 18–28 | 8 | 44.4 |

| 29–39 | 9 | 50.0 |

| ≥40 | 1 | 5.6 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 11 | 61.1 |

| Male | 7 | 38.9 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 6 | 33.3 |

| Single | 12 | 66.7 |

| Education | ||

| High school | 1 | 5.6 |

| Undergraduate | 14 | 77.8 |

| Graduate | 3 | 16.7 |

| Total work experience (years) | ||

| 1–3 | 4 | 22.2 |

| 4–6 | 4 | 22.2 |

| ≥7 | 10 | 55.6 |

| Institution | ||

| City/university hospital | 10 | 55.6 |

| State hospital | 6 | 33.3 |

| Family health center | 2 | 11.1 |

| Department | ||

| Inpatient services | 9 | 50.0 |

| Operating room | 2 | 11.1 |

| Intensive care | 3 | 16.7 |

| Emergency department | 1 | 5.6 |

| Other | 3 | 16.7 |

| Reason for providing service in the earthquake area | ||

| Already working in the region | 6 | 33.3 |

| Commissioned due to the disaster | 3 | 16.7 |

| Volunteer | 9 | 50.0 |

| Field of service in earthquake zonea | ||

| Triage | 7 | 38.9 |

| Patient transport | 2 | 11.1 |

| Outpatient diagnosis and treatment | 15 | 83.3 |

| Emergency surgery | 3 | 16.7 |

| Evacuation of patients from the hospital | 2 | 11.1 |

| Primary care services | 6 | 33.3 |

- a More than one option was marked.

| Previous disaster experience | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 13 | 72.2 |

| No | 5 | 27.8 |

| Type of previous disaster experiencea | ||

| Earthquake | 13 | 72.2 |

| Flood | 1 | 5.6 |

| Status of having been influenced by previous disaster (loss of a family member, injury, damage to the house, etc.) | ||

| Yes | 4 | 22.2 |

| No | 14 | 77.8 |

| Status of having received disaster education | ||

| Yes | 3 | 16.7 |

| No | 15 | 83.3 |

| Working in line with the plans after the disaster in the institution of employment | ||

| No | 18 | 100.0 |

| Being aware of the disaster plan of the institution of employment | ||

| Yes | 1 | 5.6 |

| No | 15 | 83.3 |

| Somewhat | 2 | 11.1 |

| Reasons for not knowing the disaster plan of the institution of employmenta | ||

| Having been uninformed | 11 | 64.7 |

| Lack of coordination | 17 | 100.0 |

| Organized as paper work | 14 | 82.4 |

| Knowing the safe areas of the institution of employment during an earthquake | ||

| Yes | 5 | 27.8 |

| No | 12 | 66.7 |

| Somewhat | 1 | 5.6 |

| Previous experience with working in a disaster area | ||

| Yes | 2 | 11.1 |

| No | 16 | 88.9 |

| Experiences with the earthquake that affected 11 provinces on February 6, 2023a | ||

| Experiencing the earthquake firsthand | 6 | 33.3 |

| Injury to self/family members in the disaster | 4 | 22.2 |

| Losing family members/acquaintances in the disaster | 7 | 38.9 |

| Damage/loss of home/workplace in the disaster | 6 | 33.3 |

| Damage to/loss of workplaces of family members/acquaintances during the disaster | 3 | 16.7 |

| Experiencing the second major earthquake | 18 | 100.0 |

- a More than one option was marked.

| Theme 1: Personal challenges |

|---|

|

Psychological well-being “When it gets dark, we get scared. We are cold. We can't sleep…. We are not expecting to sleep. While we are waiting, we fall asleep and then we feel grateful that we wake up.” (P5) “One of the difficulties was to work with that psychology as an earthquake victim… It is difficult to handle it. It requires resilience.” (P1) “When we first saw our colleagues, we felt very upset and wept into tears. Many of our friends passed away. Those who came to the hospital and we were all earthquake victims. Everyone was working desperately.” (P3) “Part of the building where we were working had cracks on the walls, and some of its columns were separated.” (P13) Emotional turmoil “I was not badly affected by this process. But there was a feeling of inadequacy. I wish I could have done more.” (P11) Two fronts and one struggle: family and work “Because my family was also in the earthquake region, I did not hear from them at first. Later, we were able to communicate by phone.” (P1) “I had to take my children out of the province…” (P5) |

| Theme 2: Organizational challenges |

|

Personnel management problem in the disaster area “We suffered a lack of fast and effective coordination. We set off from Ankara as a group of healthcare workers from five provinces, but they did not know we were coming. We arrived at the airport at 3 am and waited until 8 am.” (P13) “I have been working for one year in the neurosurgery department. I have never seen a child patient before. I worked in a pediatric ward but I didn't even dare to open an intravenous line. That's why I stayed in the background.” (P16) “There was literally a coordination problem. At first, they didn't even know we had arrived. There was no place to stay and no planning. At first, we went to an area where there was no need.” (P7) “During the first two days when we arrived, they didn't even know about our arrival. When we arrived there, we stayed at the airport from six in the evening until two in the morning. Nobody contacted us. Later, we were told that a coordination chief physician had been appointed, and then we were sent to regions where we were needed.” (P8) Crisis management problem in the disaster area “Since it was an earthquake zone, it was incredibly difficult to access medical material and consumables. We had a hard time in this regard.” (P8) Basic needs problem “We couldn't find a piece of bread and any water on the first day…” (P4) “After we left the buildings, it rained and snowed for a week. It was freezing. We had to wait outside in the cold. We slept in a car for the first week. There was a shortage of places to stay. We experienced shortcomings in terms of shelter, nutrition, and hygiene. Electricity went out and there was no running water. The aid did not arrive for almost a week.” (P18) |

| Theme 3: Nursing during the disaster |

|

Professional emotional turmoil “I chose this profession unintentionally. Helping someone makes you feel relieved. I would like to work more if possible. This is how we get distracted. We are so worthless; we have understood it.” (P12) “We have understood once again how valuable our profession is. We both provided physical care there and had a considerable impact on people spiritually. We provided complete care physically, socially, and psychologically.” (P7) Changing nursing care concept “It has changed… apart from inpatient treatment institutions… We tried to provide not only holistic or physical care but also supportive care for patients by addressing the issue of how we should approach better than what we are already doing.” (P11) “I have realized once again that eye contact and communication are very important. Maybe I don't know the other person's language, but I have understood the importance of supporting him/her by touching and understanding his/her gestures and facial expressions. To me, nursing care was not about administering that medicine or doing the dressing.” (P9) “Since many of them did not have their families with them, it was necessary to follow their treatment and make them feel that we were with them psychologically, just like their children and their fathers.” (P14) “We came to make them feel they were not alone, apart from providing nursing care services. They assigned this task to us, and we continued it.” (P8) “I couldn't approach people as a nurse. Rather, I approached them as if they were my parents. Many of my friends passed away, and I always approached the people there as if they were my deceased friends… I tried to talk to them to say that we were with them.” (P6) |

| Theme 4: Expectations |

|

Preparedness “I think all hospitals should be tested for earthquake resistance and sustainability and all hospitals should be inspected. Gathering areas should be determined. The staff must be seriously trained. Exercises must be carried out seriously and quickly. We should be prepared for possible earthquakes in this way.” (P10) Being us “As an earthquake victim, both working and living in that region is definitely a negative situation. Due to the magnitude of the earthquake, there was a lot of death and destruction. I think it would be more appropriate for people to start working for at least 5–6 months later after their shelter and psychological needs have been met. We experienced the earthquake on February 6, and two weeks later the governorship sent a letter saying legal action would be taken against those who did not come to work.” (P5) |

Qualitative data

The study identified several key themes that capture the multifaceted experiences of healthcare professionals, particularly nurses, during disaster situations. These themes provide insight into both personal and organisational challenges faced in such high-pressure environments. Through an in-depth analysis, four primary themes emerged: personal challenges, organisational challenges, nursing during disaster, and expectations. Each theme is further divided into sub-themes, shedding light on the psychological, emotional, and professional dimensions of disaster response from the nursing perspective.

Theme 1: Personal challenges

Psychological well-being

I witnessed the deaths of my relatives, cousins, and friends. There were babies with unrecognizable faces. I was highly impacted by this situation because I am sensitive toward babies. I saw dead bodies everywhere. I couldn't go home… I witnessed the whole scene; you cannot help but be affected. (P2)

Emotional burden

I was suffering less because I was in a somewhat better position compared to them, I had the opportunity to work, and I had lost fewer relatives. This situation, this feeling I felt, made me feel ashamed and pushed me to help them more. (P5)

Two fronts and one struggle: family and work

We were commuting between home and the hospital. People who had close relatives out of the earthquake region sent their children as there was no place to stay. I sent my daughter to Mersin to my friend. I enrolled her in a school there so that her mood would improve. (P12)

Theme 2: Organizational challenges/lack of coordination

Personnel management problem

The lack of aid and coordination on the first two days exhausted us. There were teams coming to help, but they did not know what was where. (P4)

Crisis management problem

We tried to make up for the loss of personnel. We had to constantly evacuate patients due to the aftershocks. There were many patients and a shortage of materials. There was limited space to work. There was constant uncertainty. There was a constant flow of patients to the hospital rescued from the rubble. They had no one in company; neither relatives nor family members. Sometimes, we could not find a doctor when the patient intensity increased. The systems were not working properly. Then, dead bodies were coming. The names and ID numbers of many of them were not known. Therefore, patient records could not be kept…. (P18)

Basic needs problem

'On the first day, there was no water or food. Most shops were closed and those that were available were looted. No help arrived, either…. It started to arrive after the 3rd day. There was also a shortage of toilets. There was no water, no electricity; literally nothing. Our biggest challenge was accommodation. I had just been given a container house; I had a lot of friends who had not been given a container. We had been working for three months, but we had no place to stay. (P3)

Theme 3: Nursing during the disaster

Professional Emotional turmoil

'Working as a nurse, especially during the earthquake, made me even more alienated from nursing. I don't think this profession can be maintained. It has no value, both because of the people and the management… I think we are both the most oppressed and the least valued group in the healthcare system. (P5)

Changing nursing care concept

You cannot think that you are nurses there. The only thing you can focus on is saving lives. As you may have seen in the media, our emergency room and corridors were full of corpses. I was just trying to save lives…. I didn't think about anything else. (P4)

Theme 4. Expectations

Preparedness

I think the most important thing to do is to educate everyone, to minimize coordination problems, and to be prepared. As we live in an earthquake zone, it is very important to raise public awareness. (P8)

Being us

Some of the nurses emphasized on obtaining feedback from staff in the disaster area and using effective communication channels. To better manage the disaster process, staff working in the earthquake region, who were earthquake victims themselves, should not be victimized further.

“The people coming there need to know that they are there to help victims”. They need to put their interests and ambitions aside because their approach should be “we did it,” not “I did it.” Even greeting and welcoming the teams arriving there and using warm language change many people's perspectives. We were shaken seriously in the 6.4-magnitude earthquake; we were trapped inside the building. When we left the building the next day, there were authorities passing by us, some of whom left without saying, “An earthquake occurred yesterday and you were inside. We hope you're alright.” We also saw administrators who said, “Why did you come here; why are you here?” (P8)

DISCUSSION

In this study, the experiences of nurses who worked/volunteered in the three provinces that were severely hit by the earthquake during the first two weeks following the disaster were examined. Almost all of the nurses had no professional disaster preparedness training. The data obtained from this study revealed four different themes: (1) personal challenges, (2) organizational challenges, (3) nursing during the disaster, and (4) expectations.

During the disaster, many factors, such as “emotional turmoil due to the mourning of the dead and the joy of the survivors,” “security problems,” and “family and work dilemma” significantly, strained nurses’ psychology. Nurses need knowledge and skills on psycho-emotional stress management in disasters (Akbari et al., 2018), providing psychological support to survivors (Li et al., 2017), and coping with stress due to witnessing the death of a large number of people (Adelman & Legg, 2009). However, some studies have shown that they are not prepared for disaster psychology (Said & Chiang, 2020; Dehkordi et al., 2021; Uran and Yildirim, 2023). Nurses’ exposure to traumatic events without preparation may hinder provision of effective care and cause negative psychological consequences in the short and long term (Kaplan & Keser, 2021). Psychological preparedness helps nurses cope with difficulties, reduce burnout, empathize with traumatized individuals, recognize sources of motivation, and use disaster experiences as a source of strength. It also encourages acceptance and taking responsibility (Akbari et al., 2018; Said & Chiang, 2020; Santinha et al., 2022). For this reason, resilience training should be included in disaster-related training.

Coordination is an important factor in disaster preparedness (Songwathana & Timalsina, 2021). In this study, it was determined that the crisis in the disaster area could not be managed due to a lack of coordination. The majority of nurses were assigned duties out of their branches. Similar problems were reported in a study conducted in China (Li et al., 2017). In a study on nurses’ disaster management competencies, Akbari et al. (2018) emphasized the need for “evaluation of necessary human and other resources” and “operational coordination and management of resources” under the theme of “management of human and other resources.” These results show that multidisciplinary preparedness and nurses’ crisis management competencies are needed (ICN, 2009). Establishing crisis management plans in mass casualty events and familiarizing staff with them is an important step toward organizational preparedness. Chaos and crisis management problems can be prevented by preparing for them in advance (Goniewicz & Goniewicz, 2020).

In the study, nurses experienced professional emotional turmoil while struggling with challenging conditions. They were satisfied with their job as they could help people in difficult circumstances, but they felt the profession did not receive the recognition it deserved. In a study of disaster volunteers involving doctors and nurses in Malaysia, Chen et al. (2020) reported that healthcare workers found their work in the earthquake zone satisfactory despite the challenging conditions. This finding in our study may have been because of the inclusion of nurses who were also earthquake victims, were unprepared for the disaster, and had to leave their families behind. Feeling worthless professionally reduces motivation and affects effective caregiving. Therefore, the needs of nurses' families such as security and shelter should be met and a gradual assignment plan should be made.

The competence of nurses in disaster response plays an important role in reducing the negative consequences on the health of people affected by disasters (Soltani Goki et al., 2023). In this study, the majority of nurses worked in outpatient diagnosis and treatment services. Most of them often needed to provide psychologically supportive care, in addition to physical care, to keep individuals alive. In a study on the examination of nurses' ethical care experiences during an earthquake, themes such as moral support, respect for human values, respect for victim dignity, commitment to ethical values, effective communication, and supportive care needs were emphasized within the framework of ethics (Moradi et al., 2020). A systematic review showed that one of the core competency areas required for nurses in disasters was “communication skills” (Al Thobaity et al., 2017; Songwathana & Timalsina, 2021). The knowledge and skills required may vary depending on the area served in the disaster region. But disaster conditions may require working anywhere. For this reason, nurses' psychological care skills and ethical values that prioritize humans should be improved.

In the study, complete preparedness for disasters was nurses’ most basic expectation. Almost all of the nurses stated that they had not received disaster-related training due to a lack of coordination, knowledge, and practical training and that they were not aware of the disaster plan of the institution they worked for. Similarly, İytemür and YEŞİL (2020) revealed that young and new nurses were not aware of hospital disaster and emergency plans. Supporting these results, many studies have shown that nurses are not prepared for disaster response (Labrague et al., 2018; Younos et al., 2021). Factors hindering preparedness are the newness of disaster nursing as a field of expertise, inadequate preparation, poor formal education, lack of research, ethical and legal issues, nurses' roles in disasters, and institutional issues (Al Harthi et al., 2020). There is an internationally growing consensus that nurses must have the basic knowledge and skills to effectively cope with the challenges of disasters (ICN, 2009). To reduce the impact of disasters, nurses need to be prepared for emergency response and crisis management. In particular, training in disaster nursing and real and simulated disaster drills are highly recommended strategies (Aliakbari et al., 2015; Sarik & Cengiz, 2022).

Another expectation of nurses was that all healthcare professionals would have an awareness of working with the “we” spirit in a crisis environment. This result emphasized the need for organizational culture. Although there is no information about organizational culture in natural disaster–related studies, the need for organizational climate was mentioned in a study on the pandemic (Hong et al., 2022). The characteristics of our study group may have been effective in revealing the need for organizational culture. Especially earthquake-affected nurses reported that they needed unity messages, motivation, and guidance from their superiors. Peng et al. (2022) emphasized the necessity of communication and collaborative practice environments within the healthcare team to reduce burnout in a crisis environment. Blanco-Donoso et al. (2020) stated that the support that could encourage healthcare professionals to fight safely, help them control negative thoughts, and alleviate their psychological burdens and aspirations was very important and that the people who would provide this support were colleagues, managers, and families. Organizational culture needs to be improved to increase the quality of care. To increase the quality of care provided and continue to fulfill duties under high stress, disaster volunteer nurses can share their disaster-related experiences in various educational environments, and thus a protective and supportive working environment can be provided.

Limitations

This study was conducted with a sample of Turkish nurses; therefore, the generalizability of the results is limited. Although the study was conducted in a single country, it is a subject worth researching and there are similar problems and results for many countries in the world. Due to the circumstances, some nurses may have avoided expressing their true feelings or may have exaggerated them. The experiences mentioned in this study belong to a large-scale disaster and reveal the situation in the most critical days of the disaster in terms of human life. This is a strength of the study. Experiences may vary depending on the type, severity, location, and scope of disasters. For this reason, the data obtained in the study focus only on the earthquake disaster. The participants were nurses who worked in the region only in the first two weeks of the earthquake. Thereafter, nurses working in the disaster area may have had different disaster nursing experiences and therefore had additional recommendations.

CONCLUSION

This study, which consisted mostly of nurses who did not have professional disaster preparedness, revealed the difficulties, coping strategies, and expectations for preparedness experienced in the disaster. The difficulties experienced were divided into two groups: personal and organizational. Within the scope of personal difficulties, “not being psychologically prepared” was identified as a factor that made managing the disaster process significantly difficult. This factor also threatened the mental health of nurses in the short and long term. Organizational difficulties, including personnel, materials, basic needs, transportation, and corpses in the disaster area, were barriers to the resolution of the crisis and therefore to the provision of effective care services. Under these conditions, nurses focused only on saving lives and provided supportive care the most. This result points to priority issues in disaster training to be given to nurses. They also expected this profession, which requires working under difficult conditions, to be appreciated more. As a result of this experience, nurses' most basic expectations included giving importance and priority to professional and organizational preparations urgently. In addition, nurses needed high motivation for better disaster management, and there was a need to create preparedness awareness at institutional, administrative, professional, and social levels to achieve this.

Implications for nursing and health policy

Imparting professional knowledge and skills for disaster preparedness to nurses can be achieved by updating the curriculum in undergraduate education, in-service training procedures in the hospital, and policies on the legal side. In case of a disaster, nurses should be encouraged to participate in various search and rescue organizations, in addition to providing health services in their institutions. In addition, a comprehensive legal regulation regarding their duties during a disaster process should be made. Additionally, a standard undergraduate education curriculum on disasters and disaster nursing should be created. After undergraduate education, they should be allowed to improve themselves in nursing services in disasters through training provided by search and rescue organizations or private institutions.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study design: Şenay Şermet Kaya. Data collection: Eylül Gülnur Erdoğan. Data analysis: Şenay Şermet Kaya and Eylül Gülnur Erdoğan. Study supervision: Şenay Şermet Kaya and Eylül Gülnur Erdoğan. Manuscript writing: Şenay Şermet Kaya and Eylül Gülnur Erdoğan. Critical revisions for important intellectual content: Şenay Şermet Kaya and Eylül Gülnur Erdoğan.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the nurses of this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No funding support was received for his study. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.