Nurses’ level of sleepiness during night shift

Abstract

Aims

This study aimed to determine the peak hours of sleepiness and the factors affecting the sleepiness levels of nurses.

Background

Sleepiness is commonly seen in individuals working night shifts. However, in case of nurses, this sleepiness can be a major threat to patient and staff safety.

Method

This was a prospective cross-sectional study. Data were collected between July and September 2023, and a stratified sampling method was used according to the departments in which the nurses worked. Data were collected using the Personal Information Form and Visual Analog Scale. Nurses reported their sleepiness levels at the beginning of each hour between midnight and 8:00 am.

EQUATOR checklist

The study adhered to the STROBE checklist for reporting.

Results

The mean sleepiness levels of emergency department nurses, intensive care nurses, internal or surgical clinic nurses, and all nurses were 59.75 ± 15.50, 43.53 ± 20.49, 44.67 ± 18.88, and 49.15 ± 19.67, respectively. The highest sleepiness level of the nurses was at 05:00 am. A significant correlation was found between the variables of age, gender, marital status, sleep quality, number of patients cared, working style and satisfaction with working in the department, and sleepiness level (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

Nurses working night shifts experience sleepiness (highest at 5:00 am). In addition, the sleepiness levels of nurses are affected by some personal and clinical factors.

Implications for nursing and nursing policy

Based on the results, there is a need for necessary policies regarding nurses' working hours and working conditions. To protect patient and employee safety, necessary strategies should be devised regarding the hours when nurses experience the highest sleepiness and the factors affecting sleepiness levels.

INTRODUCTION

Sleep is one of the basic and indispensable daily life activities of individuals and is a concept with physiological, psychological, and social dimensions (Gatchel et al., 2021). Sleep, which has a multidimensional structure and cycles with wakefulness, is referred to as the circadian rhythm. This rhythm is considered a biological clock, and it may be disrupted for various reasons and lead to sleep difficulties. Circadian rhythm sleep disorders are frequently experienced in occupational groups working in shifts (Di Muzio et al., 2019; Dubessy & Arnulf, 2023). Nursing, which plays an important role in health services, provides services every hour of every day of the week and is organized in shift work. In Turkey, nurses work 8-hour day shifts, 16-hour night shifts, and full day shifts of 24 hours. For these reasons, circadian rhythm sleep disorders are common in the nursing profession (Sadat et al., 2016a).

BACKGROUND

According to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, “sleepiness” has been reported to be an important factor in many sleep disorders (Sateia, 2014). Sleepiness can cause family and social problems, accidents, and problems at work (Selvi et al., 2016). From the point of view of healthcare personnel, this situation leads to many problems, especially for employees and patient safety (Härmä et al., 2019). Studies have emphasized the negative effects of sleepiness on patient safety in nurses working in shifts (Di Muzio et al., 2019; Gander et al., 2019). In addition, studies on healthcare workers have found that sleepiness during shift work has a negative impact on the health and well-being of staff (Kecklund & Axelsson, 2016). In this context, sleepiness can be recognized as an important health and workplace issue.

The effects of night-shift sleepiness should not be confused with the effects of daytime sleepiness. Daytime sleepiness is counterbalanced by increased waking pressure later in the day, whereas sleepiness at night is intensified later in the night as the pressure on wakefulness decreases (Dubessy & Arnulf, 2023). For this reason, it appears that sleep disorders are common in individuals working night shifts and that this situation is associated with various negative effects, such as fatigue and workplace errors (Härmä et al., 2019; James et al., 2017). Researchers have tried to find the most effective methods of altering circadian rhythms and encouraging compliance with night shifts to mitigate some of these effects (Lowden et al., 2019; Sakai et al., 2023). In this context, discerning the hours with the highest level of sleepiness during the night shift will contribute to these methods; however, no study has so far focused on determining the most intense sleepiness hours experienced by nurses during the night shift. Considering this gap, this study aimed to determine the hours when the level of of nurses are the most intense, as well as the factors affecting sleepiness levels. From this perspective, this study makes an important contribution to the literature.

Research questions

- What are the nighttime hourly sleepiness levels of emergency department, intensive care, and internal or surgical clinic nurses?

- What is the average sleepiness level of nurses?

- How do the sleepiness levels of nurses differ according to their demographic and occupational characteristics?

METHODS

Study design

A prospective cross-sectional study design was used in the study. A framework was created by considering “sleepiness and working conditions.” This framework addresses the personal and professional factors that may affect the sleepiness levels of nurses during night shifts, assisting in their evaluation and understanding in a more comprehensive way.

Participants

This study was conducted in a university hospital (tertiary care) located in a province in Turkey. Registered Nurses working in the hospital where the study was conducted, who were 18 years of age or older, who had at least six months of working experience, who had not used sleeping pills in the last month, and who volunteered to participate, were included in the study.

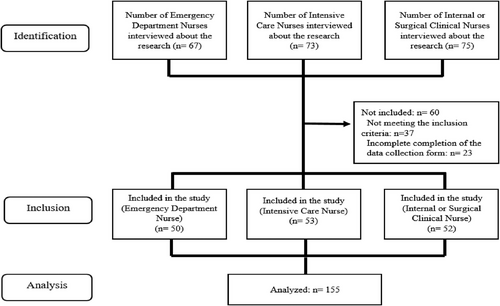

In the study, a stratified sampling method was used according to the departments in which the nurses worked. We planned to recruit equal numbers of nurses from emergency departments, intensive care units, and internal or surgical clinics. A total of 69 nurses worked in emergency departments, 217 nurses worked in intensive care units, and 694 nurses worked in internal or surgical clinics of the hospital where the data were collected, thus the population of the study consisted of 980 nurses working in these departments. For the sample of the study,data were collected from 53 nurses from intensive care, 52 nurses from the internal or surgical clinic, and 50 nurses from the emergency department; thus, a total of 155 nurses constituted the sample of the study; the flow diagram is provided in Figure 1.

A post-hoc power analysis was performed using the G*Power program, using the average Visual Analog Scale score at 05:00 am, when insomnia peaks. As a result of the analysis, the effect size was determined as 0.92, and accordingly, when effect size: 0.92, n = 155, and alpha: 0.05 were calculated, the study power was determined as 99%. Since the sample size of the study became sufficient, the data collection process was terminated.

Data collection tools

Data were collected using personal information form and visual analog scale to determine the level of sleepiness.

Personal information form

The personal information form was prepared by the researchers and included socio-demographic characteristics of the nurses (age, gender, education level, marital status, etc.), as well as some professional characteristics (total working time in the profession, average weekly working time, working type, etc.).

Visual analog scale

The visual analog scale (VAS) is one of the pain rating scales first used by Hayes and Patterson in 1921 (Delgado et al., 2018). The scale is frequently used in clinical research to measure the intensity or frequency of various symptoms, including pain (Johnson, 2001; Klimek et al., 2017). In the study, the VAS was selected to measure the severity of sleepiness and to quantify the level of sleepiness that could not be measured numerically. On the two ends of a 100-mm line, two extreme definitions of the sleep parameter were written, and the nurses were asked to indicate where their own situation corresponded on this line by drawing a line, placing a dot or pointing. “0 mm” indicated not sleepy at all and “100 mm” indicated very sleepy. The nurses denoted the severity of sleepiness they felt on this ruler at the beginning of each hour between midnight and 8 am. Sleepiness severity score measurements were evaluated in milliliters.

Data collection

Data were collected between July and September 2023 at a university hospital (tertiary care) in one of the largest cities in the Central Anatolia region. In this institution, where permission was obtained for the study, nurses work in the night shift between 04:00 pm and 08:00 am. There are two types of shifts in a 24-hour work schedule: day shift (08:00 am and 04:00 pm) and night shift (04:00 pm and 08:00 am). The work schedule is organized on a weekly basis, and nurses work alternately between day and night shifts. A nurse who finishes a night shift is required to have at least 24 hours of rest and according to legal regulations, nurses work a minimum of 40 hours and a maximum of 56 hours per week. The number of nurses on night duty varies depending on the department and the number of patients during the shift. In the emergency department, there are between six and eight nurses on duty, while in the intensive care units, there are between two and four nurses, whereas in the internal or surgical clinic, there are also between two and four nurses on duty. There is no designated time for rest or breaks during the duty period; however, nurses may rest in the nurses’ rooms when there is no work.

A stratified sampling method was used, and data were collected from emergency departments, intensive care units, and internal or surgical clinics. Data were collected by all researchers and shared among departments. One of the researchers who worked in the emergency department was responsible for the emergency department nurses. The other two researchers were granted responsibility for intensive care nurses and for internal or surgical clinic nurses. As the number of emergency departments and intensive care units and the number of nurses working in these areas were accessible, all units in these areas were reached. As the number of internal or surgical clinics and working nurses was high, a random data collection method was used to collect data in these areas. All internal or surgical clinics in the hospital were listed and randomization was conducted using computer software. Data collection commenced from the clinic listed first, proceeding in the order of the list until sufficient sample size was achieved. The internal or surgical clinics from which data were collected are as follows, according to the randomization list: general surgery clinic, cardiology clinic, gastroenterology clinic, gynecology and obstetrics clinic, chest diseases clinic, orthopedics and traumatology clinic, urology clinic, infectious diseases and clinical microbiology clinic, skin and venereal diseases clinic, neurology clinic and endocrinology and metabolism clinic.

The researchers visited the departments they were responsible for between 04:00 pm and 06:00 pm and interviewed the nurses. The participants were informed about the study and those who agreed to participate in the study were asked to sign a written informed consent form. The Personal Information Form and the Visual Analog Scale were used to determine the level of sleepiness. The data collection form was explained to the volunteer nurses. VAS used to determine the level of sleepiness was filled in at the beginning of each hour, between midnight and 08:00 in the morning. There was no harm in filling in the data between ± 5 minutes at the beginning of the hour. However, if the data could not be filled in for any reason (forgetting, intervening in a patient in need of emergency care, etc.) outside of these flexible periods at the beginning of the hour, nurses were asked to leave the study. Nurses who agreed to participate in the study were sent a reminder via WhatsApp, at 02:00 and 05:00 at night. At 08:00 am, the shift handover time, the researchers went to the departments and retrieved the data collection forms from the nurses in a sealed envelope.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA). Descriptive data were assigned as number, percentage, mean, and standard deviation. The normal distribution of the data of numerical variables was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk normality test and Q-Q graphs. As all the data were normally distributed, an independent sample t test was used for two group comparisons, and one-way analysis of variance was used for comparisons of three or more independent groups. The post-hoc test was applied to the significant data as a multiple comparison test. The Pearson correlation analysis was performed to determine the relationship between numerical data, the direction, and the severity of this relationship. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

Before starting data collection, approval was obtained from the local ethics committee (May 5, 2023, number 57068). In addition, the Academic Board Decision and written institutional permission were obtained from the institution where the study was conducted. The purpose of the study was explained to all participating nurses before data collection, and they were informed that the data obtained from the study would be kept confidential and used exclusively for scientific purposes. Written informed consent was obtained from all nurses who agreed to participate in the study and care was taken to comply with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki at every stage of the study.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the distribution of demographic and occupational characteristics of the nurses. As stratified sampling was performed according to the departments where the nurses worked, the distribution of the nurses between the groups was similar. Among the nurses included in the study, 52.9% were between the ages of 25 and 34, 54.8% were of normal weight, 70.3% were female, 52.9% were married, 57.4% had children, and 63.2% had income equivalent to expenses. Of the nurses, 85.8% lived with their families, 17.4% had chronic diseases, 56.8% had moderate sleep quality, 88.4% worked in shifts, and 70.3% were satisfied with working in their department. 52.9% of the nurses worked for 5 years or less, 51.6% worked an average of 48 hours per week, and the mean number of patients cared for at the time of data collection was 12.58 ± 8.00. The mean tea consumption of the nurses was 3.49 ± 3.24 before the shift and 3.58 ± 3.68 during the shift. The mean coffee consumption of nurses was 1.19 ± 1.26 before the shift and 1.53 ± 1.60 during the shift. The mean cigarette consumption of the nurses was 2.90 ± 5.61 before the shift and 3.74 ± 6.54 during the shift. In addition, when the measures taken by the nurses to prevent sleepiness during the night shift were ranked, the top three were drinking tea or coffee (37.3%), stepping away from the environment that may cause sleepiness (15.9%), and browsing social media (13.7%).

| Characteristics | n (%) | Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Department | Working in the department | ||

| Emergency service | 50 (32.3) | Satisfied | 109 (70.3) |

| Internal or surgical clinic | 52 (33.5) | Not satisfied | 46 (29.7) |

| Intensive care | 53 (34.2) | Total working time in the profession | |

| Age | (Years) | ||

| <25 | 40 (25.8) | ≤5 | 82 (52.9) |

| 25–34 | 82 (52.9) | 6–10 | 37 (23.9) |

| ≥35 | 33 (21.3) | ≥11 | 36 (23.2) |

| BMI | Average weekly working time | ||

| Underweight (≤18.9) | 6 (3.9) | 40 hours | 43 (27.7) |

| Normal weight (19–24.9) | 85 (54.8) | 48 hours | 80 (51.6) |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 53 (34.2) | 56 hours | 32 (20.6) |

| Grade I obese (30–34.9) | 11 (7.1) | Number of patients provided care | |

| Gender | (Mean ± SD) | 12.58 ± 8.00 | |

| Female | 109 (70.3) | Tea consumption | |

| Male | 46 (29.7) | Before shift (mean ± SD) | 3.49 ± 3.24 |

| Marital status | On shift (mean ± SD) | 3.58 ± 3.68 | |

| Married | 82 (52.9) | Coffee consumption | |

| Single | 73 (47.1) | Before shift (mean ± SD) | 1.19 ± 1.26 |

| Having a child | On shift (mean ± SD) | 1.53 ± 1.60 | |

| There is | 66 (42.6) | Cigarette consumption | |

| No | 89 (57.4) | Before shift (mean ± SD) | 2.90 ± 5.61 |

| Economic status | On shift (mean ± SD) | 3.74 ± 6.54 | |

| Income less than expenditure | 41 (26.5) | Measures to prevent sleepiness | |

| Income matches expenditure | 98 (63.2) | during the night shift* | |

| Income more than expenditure | 16 (10.3) | Drinking tea or coffee | 82 (37.3) |

| Who lives with | Getting away from the environment | 35 (15.9) | |

| Alone | 22 (14.2) | that can cause sleepiness | |

| Family | 133 (85.8) | Smoking | 12 (5.4) |

| Chronic disease | Navigate social media | 30 (13.7) | |

| There is | 27 (17.4) | Face washing | 20 (9.1) |

| No | 128 (82.6) | Reading a book | 15 (6.8) |

| Sleep quality | Listening to music | 7 (3.2) | |

| Good | 9 (5.8) | Have a snack | 9 (4.1) |

| Middle | 88 (56.8) | Chatting | 10 (4.5) |

| Bad | 58 (37.4) | ||

| How it works | |||

| Perpetual night | 18 (11.6) | ||

| Shift changing | 137 (88.4) |

- * More than one option was selected. BMI: Body mass index.

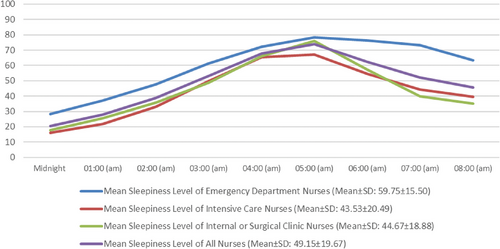

In the study, stratified sampling was performed according to the departments where the nurses worked and the distributions between the groups were similar (Table 1). Graph 1 shows the sleepiness levels of the nurses according to the departments and the average of the three groups. The mean sleepiness levels of emergency department nurses, intensive care nurses, internal or surgical clinic nurses, and all nurses were 59.75 ± 15.50, 43.53 ± 20.49, 44.67 ± 18.88, and 49.15 ± 19.67, respectively. The peak hour of the sleepiness levels of the nurses was 05:00 am. The sleepiness levels of the nurses increased regularly until 05:00 am and then decreased regularly until the handover time.

A comparison of the mean sleepiness levels of nurses with some variables is given in Table 2. When the mean sleepiness levels of the nurses were compared according to the departments in which they worked, the sleepiness levels of the emergency department nurses were statistically significantly higher than the other departments (P < 0.05). In addition, there was a statistically significant relationship between the variables of age, gender, marital status, sleep quality, working style and satisfaction with working in the department, and sleepiness level (P < 0.05).

| Characteristics | Mean sleepiness level | Characteristics | Mean sleepiness level | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Test | Mean ± SD | Test | ||

| Department | Economic status | ||||

| Emergency service | 59.75 ± 15.20a | F:12.335 | Income less than | 46.36 ± 19.44 | |

| Internal or surgical clinic | 44.67 ± 18.88b | P < 0.001 | expenditure | F:1.371 | |

| Intensive care | 43.53 ± 20.49b | Income matches | 51.10 ± 19.40 | p:0.257 | |

| Age | expenditure | ||||

| < 25 | 57.20 ± 18.01a | Income more than | 44.37 ± 21.49 | ||

| 25-34 | 45.55 ± 18.67b | F:4.994 | Expenditure | ||

| ≥35 | 48.35 ± 21.66b | p:0.008 | Sleep quality | ||

| Gender | Good | 36.91 ± 15.78a | F:9.547 | ||

| Female | 45.09 ± 19.42 | t:−4.165 | Middle | 45.05 ± 19.83a | P < 0.001 |

| Male | 58.78 ± 16.86 | P < 0.001 | Bad | 57.27 ± 17.13b | |

| BMI | How it works | ||||

| Underweight (≤18.9) | 57.77 ± 20.41 | Perpetual night | 59.47 ± 15.22 | t:2.403 | |

| Normal weight (19–24.9) | 46.70 ± 17.82 | F:2.457 | Shift changing | 47.80 ± 19.83 | p:0.017 |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 53.76 ± 21.66 | p:0.065 | Working in the | ||

| Grade I obese (30–34.9) | 41.21 ± 19.15 | department | |||

| Marital status | Satisfied | 46.64 ± 19.99 | t:−2.496 | ||

| Married | 44.56 ± 19.61 | t:−3.168 | Not satisfied | 55.10 ± 17.20 | p:0.014 |

| Single | 54.31 ± 18.55 | p:0.002 | Total working time in | ||

| Having a child | the profession (years) | ||||

| There is | 49.60 ± 20.40 | t:0.243 | ≤5 | 49.02 ± 19.70 | F:0.329 |

| No | 48.82 ± 19.22 | p:0.808 | 6-10 | 51.14 ± 19.45 | p:0.720 |

| Chronic disease | ≥11 | 47.40 ± 20.19 | |||

| There is | 47.61 ± 18.26 | t:−0.447 | Average weekly | ||

| No | 49.48 ± 20.01 | p:0.665 | working time | ||

| Who lives with | 40 hours | 42.36 ± 17.89 | F:0.100 | ||

| Alone | 54.79 ± 17.53 | t:1.457 | 48 hours | 49.09 ± 20.00 | p:0.905 |

| Family | 48.22 ± 19.91 | p:0.147 | 56 hours | 58.43 ± 17.79 | |

- BMI: Body Mass Index, F: One-Way ANOVA, t: Independent Sample t Test.

- a, b superscripts indicate the difference within the group and the same letters indicate that there is no difference within the group and different letters indicate that there is a difference within the group.

The correlation analysis between the average sleepiness levels of nurses and some numerical variables is presented in Table 3. As a result of the statistical analysis, it was determined that there was a significant positive correlation between the number of patients cared for and the average sleepiness level.

| Mean sleepiness level | |

|---|---|

| Number of patients provided care | 0.395* |

| Tea consumption (before shift) | −0.068 |

| Tea consumption (on shift) | −0.033 |

| Coffee consumption (before shift) | −0.061 |

| Coffee consumption (on shift) | 0.026 |

| Cigarette consumption (before shift) | −0.006 |

| Cigarette consumption (on shift) | 0.002 |

- r: Pearson correlation analysis; * P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Since the second half of the 20th century, human sleep has become a highly complex, physiological state influenced by many internal and external factors (Sateia, 2014; Troynikov et al., 2018; Worley, 2018). Studies on sleep should be focused especially on occupational groups working on night shifts. The findings of this quantitative study are based on the experiences of a total of 155 nurses working in intensive care units (53), internal or surgical clinics (52), and emergency departments (50), and it reports on the level of sleepiness during the night shift, as well as the contribution factors.

Shift work often causes symptoms of sleepiness, which can lead to a decrease in workplace productivity and performance (Sadat et al., 2016; Sakai et al., 2023). In the study, the sleepiness experienced by the nurses during the night shift was measured every hour and the average sleepiness levels were close to moderate, in the scale scoring. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to comprehensively measure sleepiness in nurses working night shifts on an hourly basis. Previous studies have generally focused on post-shift sleepiness. For example, Vanttola et al. (2020) found that healthcare providers working night shifts experience sleep disturbances, sleepiness, physical and mental fatigue, as well as depression in the general perspective, leading to poor memory and reduced cognitive performance (Vanttola et al., 2020). In another study, it was emphasized that nurses working night shifts experienced pathological sleepiness throughout the shift in general, not on an hourly basis (Surani et al., 2008).

We observed that the sleepiness levels of the nurses reached the highest level at 05:00 am and then decreased steadily, until the end of the shift. In the literature, it has been reported that nurses working night shifts generally experience high levels of sleep problems, at the point when their circadian rhythms are low (02.00–06.00 am) (Geiger-Brown et al., 2016). This can be explained by the fact that the need for sleep increases, as indicated in the biological cycle of the circadian rhythm, and the peak hours of sleepiness are 02.00–06.00 am (Troynikov et al., 2018). In the department-specific analysis, it was observed that nurses working in the emergency department had higher levels of sleepiness, than nurses working in intensive care and internal or surgical clinics. As emergency nurses provide health care to patients who are often unstable, they not only need to make accurate clinical assessments but also need to be highly alert and respond quickly to subtle changes in the patient's condition. This constant state of alertness is thought to predispose emergency nurses to experience higher levels of sleepiness. Emergency departments are also characterized by high patient circulation and therefore a high number of patients under care (Li et al., 2022). When examining the distribution of the number of patients cared for in the emergency department between 04:00 pm and 08:00 am, it is observed that there is an excessive workload between 04:00 pm and at midnight, which decreases somewhat between midnight and 04:00 am; the number of patients also decreases significantly between 04:00 am and 08:00 am. For this reason, it was thought that the sleepiness of the emergency service nurses who came out of an intense tempo would increase after 04:00 am.

In this study, it was observed that nurses who were dissatisfied with working in their department and thought that their sleep quality was poor had higher levels of sleepiness. Employee motivation has an important role in determining the level of productivity and work-related performance (Sharma et al., 2016); however, this situation may also be explained physiologically. It is thought that serotonin and dopamine, which are released when the individual feels good, may have a positive effect on sleep problems (Monti, 2011). From this finding, it can be concluded that the sleepiness levels of nurses can be reduced, and indirectly, employee and patient safety can be increased, by improving the working environment and practices aimed at increasing the satisfaction rate of nurses. In addition, in a study similar to our findings, it was reported that sleepiness levels were also high in people with poor sleep quality (Zare et al., 2016). Poor sleep quality can occur as a result of sleep disturbance by external or internal factors (Sadat et al., 2016; Zare et al., 2016). Therefore, working in night shifts may have negatively affected the sleep quality of nurses. It is thought that nurses with poor sleep quality have higher sleep requirements and higher sleepiness levels during the night shift, resulting from incomplete sleep periods.

It is reported that the effects of decreasing sleep status on performance are less pronounced with increasing age (Bliese et al., 2006). In our study, it was found that nurses under the age of 25 had higher levels of sleepiness. In a study on the relationship between age and sleep, it was argued that older participants exhibited more improved and stable performance over time, compared to younger participants, which was due to more effective defense against the effects of repeated circadian synchronization (Silva et al., 2010). In contrast to our findings, in another study, it was found that decreased functionality and increased sleepiness were higher in older nurses (Zion & Shochat, 2018). Some studies report that there is no relationship between age and sleep (Akbari & Hajian, 2015; Lecca et al., 2023). In this context, it is suggested that the relationship between age and sleep and sleepiness varies and should be evaluated together with other accompanying variables.

One of our study findings was that male nurses had higher sleepiness levels than female nurses. No study on this subject has been found on nurses; however, Luca et al. (2015) looked at the relationship between sleep, age, and gender and found that older participants, especially women, complained less about sleepiness and pathological sleepiness was significantly lower than younger participants (Luca et al., 2015). In contrast, health studies on shift workers report that women are more likely than men to experience sleep disturbances and difficulty falling asleep (Fatima et al., 2016; Lecca et al., 2023). The small number of male nurses in the general nurse population limits the generalizability of the data to men. The higher sleepiness levels of single nurses may be because the lifestyles of unmarried people are often irregular. The sleep problems experienced (e.g., insomnia, short sleep duration, low sleep quality, etc.) can be explained by being active 24 hours a day, as a result of the modern social structure (Matsumoto et al., 2022).

It is argued that sleep disturbances during the night shift basically cause three problems. The first is decreased alertness, falling asleep without realizing it, and increased risk of patient care errors (Estryn-Béhar & Van der Heijden, 2012). Second, an increased risk of work-related accidents and injuries, including motor vehicle accidents on the way home from work (Di Muzio et al., 2019; Estryn-Béhar & Van der Heijden, 2012). The third is the increased risk of long-term health deterioration, resulting in missed work and increased healthcare costs (Selvi et al., 2021). Our study findings support the first problem and indicate that the sleepiness levels of nurses working continuous night shifts are high. However, there are also studies in the literature reporting that there is no significant relationship between continuous night shift work and sleepiness (Sadat et al., 2016). It is thought that this difference may be affected by a number of variables, such as the number and characteristics of the population studied, the department worked in, and the number of patients cared for. Finally, it is reported that personnel working night shifts in health services are at high risk in terms of occupational safety, that they provide lower quality care and have lower job satisfaction (Estryn-Béhar & Van der Heijden, 2012). For these reasons, the problem of “sleepiness” during the night shift, especially caused by circadian rhythm disturbance, is one of the important issues that need to be emphasized and solved. In our study, determining the peak hours of circadian rhythm disturbance, which is one of the root causes of sleepiness during the shift, will make an important contribution to the strategies to be implemented.

Limitations

There are several known limitations of this study. It is not possible to generalize the results obtained because the research was conducted in a single center and in a certain period of time: The findings of the study did not measure changes over time. In addition, the number and types of independent variables examined in the study may be limited. Furthermore, the majority of participants have fewer than five years of experience; this may result in the perspectives and experiences of highly experienced nurses not being fully represented. The reason for the low number of male participants in the study is the continued predominance of female prevalence in the nursing profession: This may lead to an incomplete understanding of gender-based differences in male nurses’ night shift sleepiness levels and affect the generalizability of the results. Research should be conducted with larger sample groups, on nurses in different geographical regions and different types of hospitals.

CONCLUSION

Nurses’ sleepiness levels gradually increase every hour after midnight and peak at 05:00 am. After 05:00 am, it decreases steadily until the end of the shift (08:00 am). The sleepiness levels of emergency department nurses are higher than other departments. There is a statistically significant relationship between the variables of age, gender, marital status, sleep quality, working style and satisfaction with working in the department, and sleepiness level of nurses. In addition, there was a significant positive correlation between the number of patients cared for and the average sleepiness level of nurses.

The study provided important information about the sleepiness levels of nurses working in night shifts and the factors affecting them. Sleepiness levels of nurses may be an important parameter for patient safety and employee health. Therefore, healthcare organizations and nurse managers should plan and implement strategies to reduce the sleepiness levels of nurses. According to the data obtained from this study, it is crucial to take measures, in particular for the hours when nurses experience the highest sleepiness levels. In addition, it may be recommended to increase research on the sleepiness levels of nurses and to conduct experimental studies on reducing sleepiness levels.

Implications for nursing and health policy

In this study, it was aimed to determine the peak hours of sleepiness levels of nurses and the factors affecting sleepiness levels. Nurses’ sleepiness levels gradually increase every hour after at midnight and peak at 05:00 am. After 05:00 am, it decreases steadily until the end of the shift (08:00 am). Strategies to increase nurses' alertness can reduce potential errors and risks. This can also reduce the risks associated with legal issues and costs. Necessary measures should be taken especially for the hours when nurses experience the highest sleepiness. Hospitals and healthcare institutions should take into account the peak sleepiness hours, especially around 05:00 am, when planning nursing shifts. During these hours, additional support or rotation of staff may be necessary to ensure alertness. Since sleepiness levels vary across different departments, hospitals should implement stratified staffing plans. Departments with higher average sleepiness levels may require additional measures such as shorter shifts or more frequent breaks.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study conception/design: AK, CO, EB. Data collection/analysis: AK, CO, EB. Drafting of manuscript: AK, CO. Critical revisions for important intellectual content: AK, CO, EB. Supervision: AK. Statistical expertise: AK. Administrative/technical/material support: AK, CO, EB.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all the nurses who participated in this study and the experts who supported the research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ETHICS APPROVAL STATEMENT

The Ethics Committee of Kayseri University (No: 57068, Date: 05.05.2023)