Coping strategies in health care providers as second victims: A systematic review

Abstract

Aim

To analyze personal and organizational strategies described in the literature for dealing with the second victim phenomenon among healthcare providers.

Background

The second victim phenomenon involves many associated signs and symptoms, which can be physical, psychological, emotional, or behavioral. Personal and organizational strategies have been developed to deal with this phenomenon.

Materials and methods

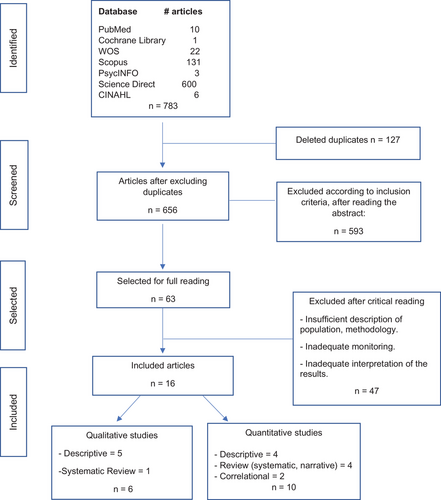

A systematic review was carried out in PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Scopus, PsycINFO, Science Direct, and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature databases, searching for evidence published between 2010 and 2019 in Spanish, English, German, and Portuguese.

Results

Seven hundred and eighty-three articles were identified. After eliminating duplicates, applying inclusion and exclusion criteria and critical analysis tools of the Joanna Briggs Institute, 16 research articles were included: 10 quantitative studies (design: descriptive, correlational, systematic, or integrative review) and six qualitative studies (descriptive, systematic review). There are several different personal and organizational strategies for dealing with the second victim phenomenon. Among these, peer support and learning from adverse events are highly valued. In personal strategies stands out the internal analysis of the adverse event that the professional performs to deal with the generated negative feelings. In organizational strategies, the most valued are second victim support programs with rapid response teams and made up of peers.

Conclusions

The main organizational coping strategies for tackling this phenomenon are online programs in countries such as the United States, Spain, and other European countries. Formal evaluation of these programs and research is required in Latin America.

Implications for nursing and health policies

Adequately coping with the second victim phenomenon allows health professionals and organizations to learn from adverse events. Furthermore, by supporting health professionals who suffer from the second victim phenomenon, the organization takes care of its most valuable resource, its human capital. This contributes toward building a culture of healthcare quality in organizations, which will reduce adverse events in the future.

INTRODUCTION

“Free from Harm” is a 2015 publication that highlights strategies for the patient's safety during healthcare (Boston, MA: National Patient Safety Foundation, 2015). Although we would like that the patient care would be risk-free, it is not, since the patient might be a victim of unexpected adverse events.

In terms of the context of the damage, adverse events may have more than one victim, which is why victims have been categorized into three groups: first victims, the patient and their family; second victims (SVs), the health professionals involved; and third victims, the organization (Seys et al., 2012).

Coined by Wu (2000) over 20 years ago, the term SV refers to health professionals who, after an adverse event, display various physical, psychological and/or behavioral responses that may even trigger suicide (Blacklock, 2012; Pratt et al., 2012).

In response to the harm that occurred to patients during care, the strategy of patient safety culture emerged. A patient safety culture can be defined as a group of initiatives that can be viewed as cogs in an overall system to enable safer care for patients (Wagner et al., 2019); and this culture has been a global concern for several decades. The publication of the report “To Err is Human” in 2000 gave figures of more than 80 000 deaths per year in the United States from adverse health events (Institute of Medicine, 2000). Twenty years later, the World Health Organization (WHO) revealed that, in high-income countries, one in 10 patients suffers an injury while receiving healthcare, and the reality is even more acute in low-income countries, where 2.6 million deaths occur per year, attributed to adverse events (World Health Organization, 2020). One publication that tracks this situation has analyzed studies carried out in 137 countries, in which 5 million people have died from deficient health services, compared to just 3.6 million deaths due to lack of access to health services (Kruk et al., 2018).

Adverse events are complex, varied, and multi-causal (Mohamadi et al., 2019). They include events related to care (pressure ulcers, patient falls, among others) related to medication, procedures, diagnosis, or infections associated with healthcare (Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality, 2016). The WHO proposes another international classification: “The Conceptual Framework for the International Classification for Patient Safety.” In this document, the incidents are classified into clinical administration, clinical process/procedure, documentation, healthcare-associated infection, medication/intravascular fluids, blood/blood products, nutrition, oxygen/gas/vapor, medical device/equipment, behavior, patient accidents, infrastructure/building/ fixtures, and resources/organizational management (World Health Organization, 2009). Another important point is that adverse events generate great expense for public health systems as they increase the costs of hospital stays per day, procedures, and medication, among other factors (Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality, 2016). It is estimated that 43 million adverse events occur every year, which equates to over $132 million in medical expenses (Hannawa et al., 2016). For example, a study carried out in Chile shows that the cost of each patient who has a permanent urinary catheter fitted and develops a urinary tract infection is equivalent to the cost of four patients with the same catheter who do not develop an infection (Kappes Ramirez, 2018).

So intense can SV's phenomena be that the signs and symptoms they develop have been standardized according to post-traumatic stress victims (Grissinger, 2014). The prevalence of the SV phenomenon has been documented in various ways. Some studies report that it occurs in approximately half of health professionals who have to deal with an adverse event in their professional life (Bleazard, 2019). A systematic review found that the prevalence of the SV phenomenon varies from 10.4% to 43.3% and that women are more afraid of losing their professional confidence or reputation than men (Seys et al., 2013).

The SV phenomenon involves many associated signs and symptoms, which may be physical, psychological, emotional, or behavioral in nature. They may be limited to the workplace, affect the individual in their daily life, or lead them to leave the profession (Scott et al., 2009). Of the professionals who overcome a serious adverse event, 15% seriously consider quitting their job (Pratt et al., 2012). Even links with burnout and suicidal thinking have been reported, with a higher prevalence among doctors who make mistakes than among the general population (Lane et al., 2018; Schanafelt, 2011).

Physical signs and symptoms of the SV phenomenon include extreme fatigue, tachypnoea, tachycardia, muscle tension, sleep disturbance, and headache. The signs associated with the psychological aspect also vary, including flashbacks or repeated memories of the event, grief, frustration, difficulty concentrating, fear, or remorse, with doubt about professional capacity being the most prevalent sign (Rinaldi et al., 2016). Other symptoms described include feelings of guilt and anxiety (Mira et al., 2015).

In a sample of 4369 nurses and doctors, the most common symptom experienced by SVs was found to be hypervigilance (53%), followed by doubts about knowledge and skills (27%). Furthermore, the intensity and duration of the reported signs and symptoms were greater when the adverse event caused patient death (Rinaldi et al., 2016; Vanhaecht et al., 2019), and these symptoms were more prevalent, lasting, negative, and stronger among nurses than doctors (Harrison et al., 2015; Vanhaecht et al., 2019).

As far as we know, the SV phenomenon can last for years, and non-resolution can lead the health professional to make mistakes that cause new adverse events, producing a spiral that is perpetuated in health centers (Pratt & Jachna, 2015).

In the end, to take care of the SV, we have to manage adverse events effectively. While the ethical imperative to “do no harm” is a fundamental principle, it is taken very literally. This is unrealistic when viewed from the perspective of the adverse event, causing the professional involved to experience guilt, anger, or shame, among other responses (Paparella, 2011; Steven et al., 2014). In reality, adverse events not only occur due to the complexity of medical and nursing actions but also due to the limitations of human actions (Hall & Scott, 2012; Paparella 2013).

For all these reasons, both personal and organizational strategies have been developed to deal with the SV phenomenon (Reis et al., 2018) that not only contribute toward the professionals' own well-being but also influence the well-being of the people they serve (Quillivan et al., 2016).

Thus, the patient safety culture, adverse events, and particularly the phenomenon of SV have been studied more in recent years.

Aim

The aim of this systematic review was to analyze personal and organizational strategies described in the literature for dealing with the SV phenomenon among healthcare providers. The following question was posed in a PICO (Population, Intervention. Comparison. Outcome) format: What strategies have been described for dealing with the physical and emotional symptoms of the SV phenomenon in health professionals who have encountered adverse events?

Ethical considerations

In this systematic review, the international research standards contained in the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinski (2008) have been followed. As a systematic review without the participation of human beings, it is exempt from approval by an ethics committee.

METHODOLOGY

A systematic review was performed, following the recommendations set out in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins et al., 2019) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist (Liberati et al., 2009).

Search strategy

To develop an approach to the subject, we began a manual search of the journals Revista de Calidad Asistencial and the Journal of Patient Safety. Experts on the subject were consulted by email, who suggested two electronic resources (Second and third victims, 2018; ihi.org).

A search was then performed from November to December 2019 using the following terms from the MeSH thesaurus: medical error [OR] adverse event [OR] SV. Then, the terms nurse [OR] nurses [OR] healthcare professionals [AND] interventions [OR] support [AND] best practices were added. The PubMed, Cochrane Library, WOS, Scopus, PsycINFO, Science Direct, and CINAHL databases were reviewed with a search of evidence published between 2010 and 2019. Documents in Spanish, English, Portuguese and German were accepted.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

- –Articles on adverse events and SVs.

- –Articles that report educational, administrative, psychological, individual, group, or organizational strategies for dealing with the SV phenomenon.

- –Articles outlining strategies focused on nurses, doctors, or other health professionals, in primary care centers or hospitals.

Editorials and duplicate articles were excluded from this review.

Methodological quality assessment

To determine which critical analysis tools to use, we consulted “Critical Appraisal Tools and Reporting Guidelines for Evidence-Based Practice” (Buccheri & Sharifi, 2017) and A Step-by-Step Guide to Conducting an Integrative Review (Remington, 2020). Our decision was to use the critical analysis tools of the Joanna Briggs Institute since this tool is specially formulated for analyzing healthcare and nursing research (Hopia & Heikkilä, 2019). This appraisal tool is designed to evaluate the methodological quality of a study and identify any possibility of bias in its design. It consists of several items that can be assessed as “yes,” “no,” or “unclear.”

The instruments used for validation were analytical cross-sectional studies, qualitative research, and systematic reviews (Lockwood et al., 2017). Only studies that met at least 60% of the criteria were included. This standard was set based on the systematic review from Chan et al., 2016. The critical evaluation was performed by two independent reviewers. For each guideline, the items answered with “yes” are considered fulfilled and those answered with “no” or “unclear” are considered unfulfilled. The result was expressed as a percentage of compliance with the guideline.

Search results

A total of 783 articles were identified through the initial database search. The PRISMA flowchart for this search is shown in Figure 1.

Analysis of the results

The articles selected for this review were ordered in a table detailing the lead author, country in which the research was conducted, year of publication, type of study, participants, quality assessment (measured as the percentage of compliance with the Joanna Briggs Institute's criteria), and main results (Table 1).

| Author | Country | Year of publication | Type of study | Participants/sample | Quality evaluation | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative studies | ||||||

| Mokhtari, Z. et al. | Iran | 2018 |

Descriptive, qualitative |

18 nurses | 80/100% | –Barriers to tackling the second victim (SV) phenomenon are bad administration, cultural and legal barriers, and inadequate information |

| Rinaldi, C. et al. | Italy | 2016 |

Descriptive, qualitative |

30 doctors, nurses and other health professionals | 80/100% |

–80% of SVs feel that they were not listened to; –82% feel that there is no support for SVs; –76% of professionals agree with the idea of a psychological support system for SVs |

| Cabilan, C.J. et al. | Australia | 2017 | Qualitative systematic review | Nine qualitative studies carried out on nurses | 100/00% |

–SV nurses choose to speak to colleagues with similar experiences; –strategies should focus on overcoming the negative emotions that are generated |

| Chan, S.T. et al. | Singapore | 2017 |

Descriptive, qualitative |

Eight nurses |

80/100% |

–Participants use their own resources to deal with the emotions of the SV phenomenon; –there is a rejection of institutional support when it is provided by strangers; –religion is used as support to relieve symptoms in SVs |

| Ferrús, L. et al. | Spain | 2016 |

Descriptive qualitative |

27 doctors and nurses | 70/100% |

–Organizations must have a formal means of reporting adverse events; –SVs need support |

|

Carrillo, I. et al. |

Spain | 2016 | Descriptive, qualitative | Hospital and primary care centre managers and 1087 health professionals | 62.5/100% |

–Proposes design of an online SV intervention program; –design of a patient safety agenda for managers; –design of a web tool for adverse event solutions (BACRA: root-cause analysis); –SV website with 2579 visits in the first year |

| Quantitative studies | ||||||

| Joesten, L. et al. | USA | 2015 | Descriptive, quantitative | 365 doctors, nurses, and other health professionals | 85/100% |

–10% to 30% of professionals say that there are support services, but 30%—60% say that these are not available; –only 37% of professionals believe that they can communicate the error without fear of retaliation |

| Harrison, R. et al. | United Kingdom–USA | 2015 | Descriptive, quantitative | 265 doctors and nurses | 62.5/100% |

–Peer support is helpful; –strategies are perceived as useful when they allow the cause of the error to be solved; –discussion of the adverse event with peers or superiors is valued; –barriers to the use of institutional support: shame and fear due to the confidentiality of the information |

| Van Gerven, E. et al. | Belgium | 2014 | Descriptive, quantitative | 59 hospitals in Belgium | 75/100% |

–Few organizations have an SV support service; –rapid response to SVs from the organization is valued; –when there are no formal SV services, it is because it is not a priority for the organization, the support is informal, or the organization does not know how to implement formal support; –hospitals that have formal support systems recommend: 1. IHI White Paper, 2. the three-tiered model; –when there is a formal SV program, its performance has not been evaluated; –blaming the SV does not contribute to quality culture nor does it ensure that the error is not repeated |

| Quillivan, R. et al. | USA | 2016 | Descriptive, quantitative | 378 nurses at a paediatric hospital | 75/100% |

–Nurses in a punitive environment develop more anguish and anxiety (p < 0.001); –non-punitive culture is associated with reduced SV distress; –support networks for SVs are important, especially peers; |

| Seys, D. et al. | Belgium | 2013 | Literature review | 21 research articles, 10 non-research articles | 70/100% |

–SV support is required: short-, medium- and long-term actions; –professionals who do not know how to access support programs; –the role of peers in SV support is important; |

| Zhang, X. | China | 2019 | Correlational, cross-sectional | 267 nurses | 75/100% |

–Increasing the support of the organization decreases anxiety in SVs, intention of rotation and absenteeism; –improvement in the quality culture of the organization contributes to the relief of SVs |

| Seys, D. et al. | Belgium | 2012 | Systematic review | 32 research articles, nine non-research articles | 80/100% |

–Scott's proposed stages of SV recovery are recognized. –coping strategies: define what happened and learn from the mistake, manage anxiety, guilt, rage, and fatigue, –the most widely used strategy is to seek social support |

| Lewis, E. et al. | USA | 2013 | Integrative review | 21 articles | 83.3/100% |

–The experience of SV nurses is different from that of other professionals; –punitive environment generates less confidence and greater anxiety; –strategies to deal with the phenomenon: communicating the error to the patient and their family (11 studies find it to be an important milestone for SV), support for SV (nurses are more likely to make constructive changes after the adverse event if they have support) |

| Mira, J.J. et al. | Spain | 2015 | Correlational, cross-sectional | 1087 nurses and doctors from eight autonomous communities in Spain | 75/100% |

–Nurses show greater solidarity with SVs in primary care than in hospitals (p = 0.019). –46.5% of professionals declare receiving support from their unit or department. Only 13.4% receive psychological counselling; –90% of professionals state that they require advice to communicate adverse events to the patient and family; –90.1% of hospital professionals require training to face adverse events |

| Chan, S.T. et al. | Singapore | 2016 | Systematic review | 30 quantitative, qualitative and mixed studies | 72.7/100% |

–12.4% of the studies are from the USA. –Three studies show that women and nurses develop more intense and negative feelings in response to the SV phenomenon; –coping strategies found: 1. facing and learning from the error is the basis for coping. It allows the SV to maintain their professional identity and move on; 2. the stages are recognized in line with Scott. For effective coping, it is important to stay away from work after the adverse event |

Due to the selected articles' heterogeneity regarding the type of design, participants, and results, it was not possible to perform a statistical analysis of the dataset. Therefore, a narrative analysis was performed as recommended when a combination of results is not feasible. In this case, results could not be combined in a meta-analysis and are presented in a table for a narrative review to summarize evidence. (Linares- Espinós et al., 2018)

RESULTS

Of the selected 16 studies, three were carried out in the United States, three in Belgium, three in Spain, and two in Singapore. The rest were conducted in Iran, Italy, the United Kingdom, Australia, and China. Twelve were conducted after 2015. The highest frequency of publications occurred in 2016 (five of the selected studies). With respect to the research approach, 10 were quantitative (design: descriptive, correlational, systematic, or integrative review) and six were qualitative (descriptive, systematic review). Regarding the participants of the studies in qualitative studies, in three of the six studies, only nurses participated; and in the other three, doctors, nurses, and other health professionals. Of the 10 quantitative studies included, in five, only nurses participated, one had a hospital as a partner and four corresponded to reviews.

This review's main findings are detailed about personal and organizational strategies to face SVs' phenomenon and the barriers that SVs encounter to approach this phenomenon.

Personal strategies for coping with the SV phenomenon

In general, several of the personal strategies for coping with the SV phenomenon are related to the stages of recovery described by Scott et al. (2009) in dealing with this.

In order, the first personal coping mechanism relates to the first stage, that is, error identification. This is usually immediate and, right from that moment, the professional may be unable to continue with direct patient care (Bleazard, 2019). Subsequently, in the second stage, professional self-reflection occurs, in which repeatedly reviewing the facts and attempting to understand what happened leads to self-learning. This brings comfort to SVs. In the third stage, despite the SVs’ fears, they seek peer support. They are concerned about their professional reputation. In the fourth stage, SVs become concerned about the work and legal aspects that may affect their profession. They may have doubts about continuing in their job. In the fifth stage, SVs seek emotional support, without being sure how or where to find it. The sixth and final stage is determined by the result of the process: surviving (moving on without forgetting), abandoning (changing jobs or profession), or prospering (growth from the experience that is useful for the professional and others) (Scott et al., 2009, cited by Rinaldi et al., 2016).

Moreover, SVs also focus on the emotions generated by the adverse event that occurred, trying to manage the anguish, guilt, rage, or fatigue. For the initial management of these symptoms, they focus on analyzing the event, trying to objectify what happened, mentally repeating all the acts prior to the event (Seys et al., 2012). It is important to note that the more damage there is to the patient, the more intense the phenomenon (Rinaldi et al., 2016; Smetzer, 2012; Tamburri 2017). This difference is even more significant in women than in men (Van Gerven et al., 2014) with no difference between years of professional practice (Treiber & Jones, 2018).

Last, engaging in spiritual or religious help is also reported as a resource for coping personally. In this respect, prayer is described as a mechanism for alleviating distress and gaining strength (Chan et al., 2017).

Organizational strategies for coping with the SV phenomenon

All organizations should have SV support programs (Tamburri, 2017). Such support programs are valued by health professionals when they are equipped to provide a rapid response (Tamburri, 2017), such as the program documented by the University of Missouri with a team capable of responding 24 h a day and 7 days a week. They also include peer support, which is valued by SVs (Cabilan et al., 2018; Bleazard, 2019; Pratt et al., 2012; Quillivan et al., 2016; Seys et al., 2013) as well as systems for helping professionals to communicate the error to the patient and family, providing support throughout this process (Bleazard 2019; Brandom et al., 2011; Joesten et al., 2015; Lewis et al., 2013; Seys et al., 2013).

It is also interesting to note the importance of the non-punitive communication of adverse events within the healthcare quality culture. Many professionals fear retaliation in the work environment and, for this reason, SV programs must emphasize user confidentiality and promote a non-punitive culture of error-reporting (Harrison et al., 2015; Joesten et al., 2015; Lewis et al., 2013; Van Gerven et al., 2014). It is worth highlighting the conclusion of Ferrús et al. (2021), who points out that establishing formal channels for SV care in organizations reduces rumors and misinformation.

Last, in organizations that have SV support programs, there is a notable emphasis on the development of online support tools. These tools are either resources created to support SVs in the hospital or links to other tools developed by other organizations, such as the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI; Conway et al., 2011), the Spanish SV Association (Segundas y terceras victimas, 2018), or models such as the one proposed by Scott, the three-tiered model (University of Missouri, 2020). The advantage of these strategies is that they are permanently available, although the dissemination of such programs is often insufficient as shown in the case of the Johns Hopkins Hospital's Resilience in Stressful Events (RISE) program (Tamburri, 2017).

Barriers for SVs

It is striking that more than 50% of the studies included in this review directly or indirectly refer to the barriers that SVs face in terms of finding help or reporting errors in healthcare.

The most widely reported barriers faced by SVs to get help is the lack of availability of support services (Joesten et al., 2015; Seys et al., 2012), inadequate or insufficient information about support services (Mokhtari et al., 2018), and the lack of an atmosphere of help in the hospital for those who make mistakes (Rinaldi et al., 2016). Another difficulty is the professionals’ fear of reporting errors, mainly due to the confidentiality of the information (Cabilan & Kynoch, 2017; Rinaldi et al., 2016), embarrassment (Cabilan & Kynoch, 2017), or fear of reprisals against them (Joesten et al., 2015). This behavior may be a response to the rejection that many SVs have encountered when reporting errors (Ferrús et al., 2021) or the punitive environment that generates even greater anxiety among professionals (Carrillo et al., 2016; Lewis et al., 2013).

DISCUSSION

This review shows that the more intense the SV phenomenon, the greater the harm to the patient (Rinaldi et al., 2016; Smetzer, 2012; Tamburri, 2017). This is because professionals experience more intense feelings such as shame, anger, and guilt when they perceive the harm done to the patient and family (Seys et al., 2012). No statistically significant differences have been found between the intensity of the symptoms and the experience of the professionals, as studies of medication errors show that the SV phenomenon occurs both in recent graduates and professionals with over 40 years’ experience (Treiber & Jones, 2018).

It is also relevant that the SV phenomenon occurs to a greater extent among women than men (Van Gerven et al., 2014), and more among nurses than doctors (Harrison et al., 2015). This may be due to the fact that most nurses are women. Moreover, female SVs suffer more stress and greater fear of loss of confidence or security (Seys et al., 2012). However, women are more likely to discuss the error and attend training programs related to the issue (Seys et al., 2012).

Another important finding is that learning from errors is essential for SVs to develop effective coping strategies (Jones & Treiber, 2018). The expert consensus made by Pratt et al. (2012) shows that organizational learning is enhanced by serious mistakes. In the study by Harrison et al. (2015), coping is only perceived as useful by the SV if, by studying the error, it is possible to identify its cause and resolve it (e.g., lack of personnel). Another author concluded that learning from errors is necessary for SVs to maintain their professional identity and move forward (Chan et al., 2016). The qualitative study by Chan et al. (2017) found that nurses are helped in the healing process as SVs by sharing experiences that can prevent other errors. Similarly, Seys et al. (2012) concluded that it is essential to review the error and learn from it. In addition, Lewis et al. (2013) reported that nurses are more likely to make constructive changes in their actions after receiving support. For this reason, learning from mistakes contributes not only to the quality culture of the organization but also to the SV's professional growth and healing process. This conclusion is directly related to the results of the SV process in which the learning result would be equivalent to the sixth and final stage of “prospering” described by Scott and cited by Rinaldi et al., 2016.

In response to the research question that started this study, of the various coping strategies, peer support is widely preferred by SVs (Cabilan et al., 2018; Bleazard, 2019; Pratt et al., 2012; Quillivan et al., 2016; Seys et al., 2013). Some studies report that the fact that support is provided by strangers is a barrier to the use of support programs (Chan et al., 2017). This is because there is greater empathy in peer support, as it is understood that peers undergo the same professional experiences and are more accessible. Thus, the implementation of peer “coaches” to support SVs has been well-appreciated. These coaches must be trained and have the ability to anticipate the steps that the organization follows when investigating adverse events, which reduces the SV's anxiety (Bleazard, 2019; Vanyo et al., 2017).

With respect to organizational coping mechanisms, it can be inferred that they are necessary and should include short-, medium- and long-term actions (Seys et al., 2012). One of the main problems is that few institutions have formal SV support programs, and those that do have formal programs do not always have the services available (Harrison et al., 2015; Joesten et al., 2015; Seys et al., 2012; Van Gerven et al., 2014). Other barriers to using organizational coping systems include the mismanagement of resources, cultural and legal barriers (Mokhtari et al., 2018), mistrust in safeguarding user confidentiality (Rinaldi et al., 2016), and poor program dissemination (Tamburri, 2017). However, several studies show that when organizational coping support services are available, professionals are willing to use them (Edrees et al., 2016; Harrison et al., 2015). This fact is important if analyzed from Denham's point of view, in terms of establishing the rights that SVs would have. The process that SVs undergo should give them the opportunity to learn and contribute to learning in relation to quality care (Denham, 2007). Another important aspect is the ethical imperative to support SVs, not only in terms of helping professionals but also promoting consistency between the organizations’ stated values and practice (Monteverde & Schiess, 2017).

Of the coping strategies available to organizations, online systems are preferred, such as the support tools developed by the Spanish SV Research Group (segundasvictimas.es, 2018), the IHI (Conway et al., 2011), and the RISE programs at Johns Hopkins Hospital (Edrees et al., 2016; Tamburri 2017), implemented by the University of Missouri (Tamburri, 2017). These programs have the advantage of being accessible and developing specific emotional support actions for SVs (Pratt et al., 2012). The great challenge is that very few of these programs have been evaluated to verify what is the real contribution to the SV healing process. In this sense, one of the few programs that have been evaluated is the RISE program, which showed a positive evaluation of use and results in 52 months (Tamburri, 2017). The countries that have developed these strategies most are the United States, Spain, and other European countries. There is very little evidence from Latin America, and a study carried out in Brazil identified the knowledge gap regarding SVs in Latin American countries, stating that there are few statistics available and still a strong punitive culture against adverse events (Bohomol, 2019).

One of the essential conclusions to draw from this review is that several authors emphasize that interventions to tackle the phenomenon of SVs must be global (Bleazard, 2019; Seys et al., 2012; Tamburri et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019). This means that efforts should be directed at the first victim (the patient and their family) with clear policies on how to communicate errors with victim support and assistance. They should also be aimed at SVs, with an organized and formal support system that helps them overcome the symptoms caused by the phenomenon and continue their career, having learned from the mistake. The organization must also integrate these experiences into its culture of quality and safety. In this respect, it has been shown that, by finding support, SVs reduce their anguish and, as a result, their tendency to change jobs or take time off work reduces (Zhang et al., 2019). Within this context, it is essential to devise and implement mechanisms that ensure health policies that shift toward systems that generate learning from medical and nursing errors.

The aim of this systematic review was to highlight the personal and organizational coping strategies available to SVs, show the state-of-the-art in different countries, and identify the most highly valued strategies.

The limitations of this review are caused by the heterogeneity of the studies analyzed, in terms of their design, scope, and methodology. Furthermore, these studies differ with respect to the type of adverse events and their severity.

New studies should be conducted, particularly in Latin America, to improve the understanding of the phenomenon and the support given to SVs.

Implications for nursing and health policies

Adverse events occur in every hospital in the world. However, hospitals differ in terms of how they deal with such events, and the most effective response comes from those that promote a culture of quality and safety, learning from mistakes and taking care of their most valuable resource: the professionals. Therefore, adequate knowledge and study of the SV phenomenon, and its coping strategies, will enable this quality culture to be nurtured, and as a result, future adverse events will decrease.

A policy of support for SVs is necessary from the perspective of health institutions, as well as maintaining an open and non-punitive policy for adverse events. To this end, nurses must be involved in quality and clinical safety policies to formulate clear policies for supporting SVs and learning from medical and nursing errors.

International guidelines are needed to facilitate learning from adverse events, specifically to develop online systems, culturally adapted for each country, for supporting SVs. In addition, training should be given to professionals to enable them to provide support to their peers who become SVs.

CONCLUSION

The SV phenomenon is complex. There is consensus that SVs need support and there are alternatives for coping at a personal and organizational level. The support most valued by SVs is peer support while the learning achieved through the support process is fundamental. This learning allows SVs to maintain their professional identity and contribute toward the quality culture of the organization. Formal evaluation of the support programs in use (mostly online) is required, as well as implementing support systems in Latin America.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study design and manuscript writing: Maria Kappes, Marta Romero-García, and Pilar Delgado-Hito. Literature search: Maria Kappes. Article evaluation: Maria Kappes and Pilar Delgado-Hito.Study supervision: Marta Romero-García and Pilar Delgado-Hito. Critical revisions for important intellectual content: Maria Kappes and Marta Romero-García.