Domestic and Family Violence Screening and Response: A Prospective, Cross-Sectional, Mixed Methods Survey in Private Mental Health Clients

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Most domestic and family violence (DFV) research has focused on establishing prevalence and screening rates in public health and community samples. This study sought to address a gap in the literature by evaluating DFV screening and response practices in a private mental healthcare inpatient service and determining if clients of the service had unmet DFV needs. A prospective, convenience sample, mixed methods, cross-sectional survey of adult inpatient mental health consumers was employed. Sixty-two participants completed the Royal Melbourne Hospital Patient Family Violence Survey. Quantitative Likert-type and categorical responses were collated and analysed descriptively (count and percentage). Free-text responses were analysed using qualitative description within a content analysis framework. Sixty-five percent of participants had been screened for at least one DFV issue, on at least one occasion, with 35% not being screened, to their recall. Twenty-three percent reported disclosing DFV concerns, 82% felt very supported by the clinician's response to their disclosure, and 86% were provided with information they found helpful. Unmet needs were identified in 13% of participants, who had wanted to disclose DFV concerns but not feel comfortable to do so. No unscreened respondents disclosed DFV concerns, highlighting the need to uphold best practice guidelines for direct enquiry. Most disclosing clients were positive about the support they received. Indicated areas for improvement were screening rates, active follow-up, increasing psychology support levels and safety planning.

1 Introduction

Similar to many countries, rates of domestic and family violence (DFV) are high in the Australian population. Studies have been conducted evaluating screening and disclosure experiences in clients of public medical and mental healthcare services. However, little is known about DFV screening and response practices in private mental healthcare services. This study sought to address this gap in the literature through a client survey.

Domestic and family violence is behaviour directed at a person within a family or kinship structure that causes the recipient of the behaviour to feel fear (Parliament of Victoria 2008). It includes intimate partner violence, domestic violence, child abuse, coercive control, emotional and psychological abuse, physical violence and threats of physical violence, financial abuse and control, witnessing or being exposed to violence and neglect (New South Wales Department of Health 2006; Parliament of Victoria 2008; Hegarty et al. 2013; Stark and Hester 2019; World Vision 2022). DFV is predominantly perpetrated by men against women and children (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2019). However, it can be experienced by people of all ages, gender identities and backgrounds. In Australian society, people more likely to be targeted by those using DFV are women between the ages of 18 and 34 years; children; older and elderly people; people with a disability; people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds; first nations people; those who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer and asexual (LGBTIQA+) and those in remote, rural or socioeconomically disadvantaged areas (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2019).

2 Background

2.1 Impacts of Domestic and Family Violence

Domestic and family violence has significant psychological, mental health and physical consequences. In victim-survivors, it is associated with increased rates of mental health conditions (Australia's National Research Organisation for Women's Safety 2020). This includes depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, alcohol dependence, other drug use, anxiety and insomnia (Campbell 2002; Iverson et al. 2015). In men who use DFV, increased rates of post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social phobia and alcohol and drug disorders have been found (Shorey et al. 2012). Further, there is a nexus between DFV and brain injury (Pritchard, Tsindos, and Ayton 2019). Many victim-survivors sustain brain injuries as a result of DFV (Brain Injury Australia Consortium 2018). Having a pre-existing brain injury also increases the likelihood that someone will become either a victim, or user, of DFV (Brain Injury Australia Consortium 2018).

These psychological and brain impairment impacts convey a high toll. DFV increases suicide risk in victim-survivors and confers the highest overall health risk (death, disability and illness) in women aged 18–45 years, above all other factors (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2018; Kavak et al. 2018). Women who are killed by their intimate partner are significantly more likely to have used physical or mental healthcare in the 12 months prior to their death, than to have accessed support from a specific DFV agency (Sharps et al. 2001).

2.2 The Role of Healthcare in Responding to Domestic and Family Violence

Mental and physical healthcare services play an important gateway role. This includes identifying signs that clients may be experiencing DFV, screening through sensitive enquiry and providing a supportive informed response with active on-referrals to specialist services that can provide assistance (Queensland Special Taskforce 2015; State of Victoria 2016; Fisher, Jones, et al. 2022; Fisher, Rushan, et al. 2022, 2023; Fisher, Troy, et al. 2023). What remains less clear is the extent to which mental and physical healthcare services are providing this gateway function, and how clients feel about the DFV screening and support they receive. A number of recent studies have indicated that across mental and physical healthcare settings, many Australian clinicians feel underprepared and under-skilled to assist clients with DFV issues (Soh et al. 2018; Fisher, Galbraith, et al. 2020; Fisher, Rudkin, et al. 2020; Withiel et al. 2020, 2022; Cleak et al. 2021; Fisher, Rudkin, and Withiel 2021; Rudd et al. 2021; Withiel, Gill, and Fisher 2021; Fisher, Rushan, et al. 2023). However, positively, through broad-based transformation change projects that include a high level of training and appropriate resourcing, services coming from a low baseline can enact significant improvements in clinician knowledge, confidence and DFV specific clinical skills (Fisher, Rushan, et al. 2023; Fisher, Troy, et al. 2023).

2.3 Healthcare Screening Practices for Domestic and Family Violence

In healthcare services in Victoria, Australia, patient experiences of DFV screening vary across settings (Fisher, Galbraith, et al. 2020; Withiel et al. 2020). In a public mental health service, 47% of clients indicated that they had been screened for DFV, with 35% of clients reporting having family violence experiences (Fisher, Hebel, et al. 2023). Unmet needs were identified in 9% of clients, who had wanted to disclose family violence concerns, but not feel comfortable to do so. Qualitative data indicated that clients believe DFV should be talked about more often. Other research has also indicated that the nature of the relationship with the healthcare professional is a factor influencing whether disclosures are made, and that clients desire more empathy and time from clinicians who assist them with these issues (Fisher, Galbraith, et al. 2020).

Current best practice guidelines for noticing the signs that DFV may be occurring in healthcare clients include a wide range of mental health symptoms (The Royal Women's Hospital 2018; Safe and Equal 2023). As such, screening for DFV is indicated in the majority of mental health clients. To our knowledge, little research has looked at DVF screening rates and practice in private mental healthcare settings, particularly in Australia. This study sought to address this gap in the literature.

2.4 Study Objectives

- Domestic and family violence screening and the clinical response received to disclosures, from a client perspective, at a private mental health service.

- The rate of screening, the nature of screening and response procedures.

- The level of unmet client DFV need(s) (if any), in this cohort.

The study was conducted prior to the roll-out of a transformational change project introducing DFV response guidelines and training at the service.

3 Methods

3.1 Setting and Research Design

The local environment was a large 204-bed private inpatient mental health hospital in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. The Melbourne Clinic treats clients with a wide range of mental health conditions and has an outpatient day program and community mobile outreach-services. Inpatient therapy programs include treatment for eating disorders, addictive behaviours, obsessive-compulsive disorder, emotional management, trauma processing and older person's mental health. At the time, the data were collected the service did not have a DFV response policy, or guideline, and service specific training had not been provided to clinical staff. Nurses are the largest clinical professional employed at the service, followed by psychologists (clinical psychologists, neuropsychologists and general psychologists) and social workers. A recent staff survey at the hospital indicated that most clinicians reported working with patients who had disclosed experiencing DFV, but that the majority of clinicians (63%) had received no training in the area, with nurses (the bulk of the clinical workforce) reporting the lowest training levels (Fisher, Jones, et al. 2022). Definitive knowledge of clinical skills, including knowledge of key DFV indicators, asking about DFV, and responding to disclosures were reported by <20% of the clinician respondents. However, despite a lack of training, qualitative responses indicated that many clinicians would provide responses that encompassed best-practice recommendations, if they received DFV disclosures from clients.

- The Melbourne Clinic inpatient.

- Aged 18 years and over.

- Able to understand spoken and written English.

- Scheduled discharge date/time within 48 h of survey completion, identified using the electronic records system.

Within the parameters of the inclusion criteria, there were no additional exclusion criteria. The final 48 h of the admission was chosen, to maximise the likelihood that any DFV screening and response interventions would have already been undertaken. Clients who meet the eligibility criteria, and could be located on their units, were approached, outside of therapy or intervention times (e.g., groups, 1:1 assessment/therapy, protected meal times on the Eating Disorders Unit), when they were alone and invited to participate in the study.

3.2 Materials

The study utilised the Royal Melbourne Hospital Patient Survey FV screening and response tool (Fisher, Galbraith et al. 2020). A copy of the Survey Tool is provided in Data S1. This survey was developed specifically for Victorian healthcare settings, with content mirroring the Victorian Family Violence Protection Act (Parliament of Victoria 2008). The survey responses were anonymous and not re-identifiable, consistent with previous research utilising this measure. This survey has been utilised in three previous studies across general medical, child and family and public mental health services (Fisher, Galbraith et al. 2020; Withiel et al. 2020; Fisher, Hebel et al. 2023). The survey included a definition of DFV on the cover page (covering: physical violence; sexual abuse or violence; emotional or psychological abuse; behaviour that is threatening, or intimidating, or in any way controls, or dominates a person or causes them to feel fear; financial or economic abuse; neglect of a vulnerable person, e.g., children, disabled, unwell or elderly and witnessing or being exposed to DFV). The survey contains categorical and Likert-type survey questions as well as a number of free-text boxes for clients to provide further qualitative information, if they choose. The survey asks questions about whether respondents received screening for DFV issues at the health service, whether they had disclosed DFV issues, and the quality of the response they received to disclosures. Clients were also asked if they had wanted to disclose DFV issues but had not felt comfortable to do so.

3.3 Procedure

Clients were fully informed of the nature of the survey before participating, including that participation was completely voluntary and that declining would not affect their treatment at the service, in any way. Consent was implied on the client's agreement to participate, as per ethics approval, and all collected data were de-identified and not re-identifiable. The survey was provided in pencil and paper format, which clients completed alone in their rooms. Clients were provided the option of having the researcher assist to complete the survey with them, if they had visual, reading or writing difficulties. This option was chosen by one client (a 90-year-old consumer). At the completion of the survey, all clients were asked if the survey had raised any concerns for them, or if there were any issues they wished to discuss further, with a clinician. A clinical response pathway was developed, so that an evidence-based best-practice response was provided, in these circumstances. This included one-on-one support provided in a private setting using the LIVES guidelines (Listen, Inquire, Validate, Enhance Safety and Support) (World Health Organization 2014). In situations of current risk, a safety plan was developed with clients, and on-referral to community DFV support organisations was provided. In cases of current risk, information was documented and the clients treating Consultant Psychiatrist was informed.

3.4 Data Analysis

Likert and categorical responses were collated and analysed descriptively. For all quantitative data, the number count and percentage of responses were provided and tabulated. Free-text responses were analysed using qualitative description within a content analysis framework, and all free-text responses were provided in tables, to allow viewing by the reader at a manifest level, in the clients' own words (Graneheim and Lundman 2004; Sandelowski 2010). The initial, qualitative analysis was undertaken by the first author. A secondary analysis was undertaken by the final author, with additions made and discrepancies rectified by mutual agreement of the two authors. Both authors are doctoral-level clinical neuropsychologists with experience in qualitative research methods and training in DFV clinical response. The STROBE and COREQ guidelines were both consulted, reflecting the observational quantitative and qualitative nature of the data collected (see Data S2 and S3).

4 Results

A total of 75 clients were approached to participate in the study, with 62 agreeing to participate (82% response rate). Of the clients who declined to participate, six were of female gender identity, five were male and two were non-binary. Declining participants spanned the 18–19 to 70–79 year age brackets. The demographic information of the clients who did participate are included in Table 1.

| Question | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Have you previously filled in this survey? | Response—No | 62 | 100 |

| What is your gender identity? | Female: Male:Non-binary | 44:17:1 | 71:27:2 |

| Age range in years | 18–20 | 4 | 6.45 |

| 20–29 | 13 | 20.97 | |

| 30–39 | 12 | 19.35 | |

| 40–49 | 11 | 17.74 | |

| 50–59 | 14 | 22.58 | |

| 60–69 | 6 | 9.68 | |

| 70–79 | 1 | 1.61 | |

| 80+ | 1 | 1.61 | |

| Primary mental health conditiona | Depression/Anxiety | 47 | 75 |

| Trauma/PTSD | 18 | 29.03 | |

| Substance use/Addiction | 13 | 20.97 | |

| Bipolar affective disorder | 11 | 17.74 | |

| Personality disorder | 7 | 11.29 | |

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder | 5 | 8.06 | |

| Eating disorder | 4 | 6.45 | |

| Other | 4 | 6.45 |

- a Some respondents ticked more than one condition.

Seventy-one percent of the respondents identified as female, 27% as male and one as having non-binary gender identity. No respondents specified previously participating in the survey, indicating no duplication of results. There was a spread of responses across age ranges. Although, only two participants were aged over 70 years, which reflects a mild underrepresentation of older participants, relative to the overall demographics of the client cohort admitted to the hospital. The majority of clients specified a primary mental health condition of Depression/Anxiety. Substance Use/Addiction and Bipolar Affective Disorder were the second and third most commonly endorsed conditions.

There were 46 points of missing data (survey nonresponse) across the participant responses (n = 6) on the key non-demographic, quantitative questions of interest (Questions 3–8), which all constituted item-level non-response (Newman 2009). This represented 3.37% of the 1364 expected data points in the data set. Meanitem imputation was used to manage the missing data, where descriptive statistics and percentages were calculated based on all available data (Newman 2009). The data set was also cleaned, such that responses that were provided but not required were removed (i.e., when participants did not apply the skip logic directed in the survey as instructed, responding to questions that were not relevant to them, based on previous response).

Participant responses to questions about being screened for DFV are shown in Table 2 (Survey Question 3). For all specified types of DFV included, the majority of participants (50%+) indicated that they had not been screened for these issues, by a clinician at the health service. Feeling unsafe at home was the most common enquiry participants reported being screened for, on at least one occasion (42%), followed by emotional or psychological abuse (40%) and threatening, controlling or intimidating behaviour (32%). In contrast, neglect, financial or economic abuse, and witnessing or being exposed to DFV were the least common issues participants reported being screened for. In total, 65% of respondents reported being screened for at least one family violence type, on at least one occasion.

| Have you ever been asked if you are experiencing the following family violence issues by a clinician at the Health Service? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, more than once (%) | Yes, once (%) | No (%) | Unsure (%) | |

| Family violence | 8.47 | 20.34 | 66.10 | 5.08 |

| Feeling unsafe at home | 16.95 | 25.42 | 52.54 | 5.08 |

| Physical violence/Abuse | 6.9 | 20.69 | 72.41 | 0.00 |

| Sexual violence/Abuse | 8.47 | 20.34 | 71.19 | 0.00 |

| Emotional or psychological abuse | 13.33 | 26.67 | 56.67 | 3.33 |

| Threatening, controlling or intimidating behaviour | 15.00 | 16.67 | 66.67 | 1.67 |

| Financial or economic abuse | 5.26 | 14.04 | 77.19 | 03.51 |

| Neglect | 5.17 | 13.79 | 79.31 | 1.72 |

| Witnessing or being exposed to family violence | 10.17 | 11.86 | 76.72 | 1.69 |

- Note: Where missing data occurred, percentages were derived, based on the total responses provided.

In response to survey question 4, respondents indicated that DFV screening had most commonly occurred during their first session, or admission, at the service. The next most common time for enquiry was during telephone consultation at intake. The timing of screening, by DFV issue screened for, is shown in Table 3.

| On which visit to the Health Service you were asked? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phone consultation/Intake (%) | First session/Admission (%) | Second to fifth session/Admission (%) | After fifth session/Admission (%) | I cannot recall (%) | |

| Family violence | 31.25 | 37.50 | 6.25 | 12.50 | 12.50 |

| Feeling unsafe at home | 26.09 | 34.78 | 13.04 | 8.70 | 17.39 |

| Physical violence/Abuse | 25.00 | 43.75 | 0.00 | 12.50 | 18.75 |

| Sexual violence/Abuse | 29.41 | 35.29 | 11.76 | 11.76 | 11.76 |

| Emotional or psychological abuse | 13.04 | 43.48 | 8.70 | 17.39 | 17.39 |

| Threatening, controlling or intimidating behaviour | 15.00 | 30.00 | 20.00 | 15.00 | 20.00 |

| Financial or economic abuse | 0.00 | 33.33 | 16.67 | 16.67 | 33.33 |

| Neglect | 0.00 | 36.36 | 9.09 | 27.27 | 27.27 |

| Witnessing or being exposed to family violence | 15.38 | 38.46 | 7.69 | 23.08 | 15.38 |

- Note: Where missing data occurred, percentages were derived, based on total responses provided.

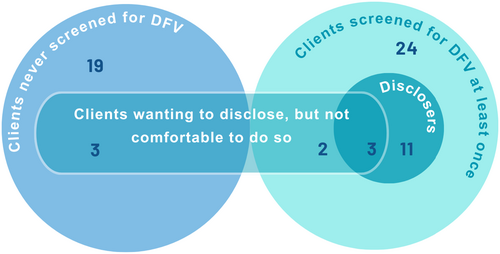

Overall, 23.33% of participants (n = 14) reported that they had disclosed DFV concerns to a staff member at the health service, 68.33% indicated they had not, and 8.33% were unsure (Survey Question 5). Spontaneous disclosure of DFV concerns did not occur in the absence of screening. All disclosing clients indicated that they had been screened for at least one type of DFV concern, on at least one occasion. Three participants indicated that they had disclosed on some occasion(s), but had not felt comfortable to do so on others. Two participants wanted to disclose DFV concerns, and had been screened on at least one occasion, but had still not felt comfortable to make a disclosure (see Figure 1).

Of the participants who had disclosed DFV concerns, 85.71% (n = 12) identified as female gender, and two as male. Thus, 27.27% of females and 11.76% of males in the sample reported DFV concerns. There was a range of age brackets in the cohort of disclosing female participants (20–29 years = 1; 30–39 years = 4; 40–49 years = 1, 50–50 years = 3; 60–69 years = 3). Both of the two disclosing male participants were in the 40–49 year age bracket. The single participant of non-binary gender indicated that they had not disclosed DFV concerns.

Participants were invited to provide further information in relation to the question about disclosure in open text-box format. Fourteen participants chose to provide information in this section, seven of whom indicated earlier that they had disclosed, six who had not, and one who was unsure. The text box responses are provided in Table 4.

| Participants who had disclosed | Response category |

|---|---|

|

Nature and type of violence |

| Barriers to disclosure | |

| Relationship of the person using violence | |

|

Relationship of the person using violence |

|

Relationship of the person using violence |

| Type of response | |

| Profession(s) of clinicians disclosed to | |

|

Nature and type of violence |

| Barriers to disclosure | |

|

Profession(s) of clinicians disclosed to |

|

Nature and type of violence |

| Profession(s) of clinicians disclosed to | |

|

Nature and type of violence |

| Profession(s) of clinicians disclosed to |

| Participants who had not disclosed/were unsure | Response category |

|---|---|

|

Unmet needs |

|

No present needs |

|

Therapeutic interventions |

|

Indirect Inquiry |

| Type of response | |

| Professions of clinician disclosed to | |

|

No present needs |

|

Indirect inquiry |

|

No present needs |

Qualitative descriptive and content analysis of the information provided by participants who had disclosed was characterised into four types. Described by categories, information was provided about the Nature and Type of Violence experienced, including verbal threats, emotional abuse, childhood sexual abuse, financial control and controlling behaviour, and the duration the violence was experienced for. Information was also provided about previous or current Barriers to Disclosure, including a lack of legal and safety protections. Information was provided about the Relationship of the Person using Violence to the victim-survivor and included male intimate partners (husbands) and male children (sons). Participants indicated that there was a range of Profession(s) of Clinicians Disclosed to (nurses, doctors, psychiatrists, social workers and program therapists) and provided information about the Type of Response received by staff to the disclosure(s), including general descriptions of support, thorough handovers and sessions with social workers.

Analysis of the responses provided by participants, who had not disclosed DFV issues (or were unsure if they had), was also undertaken. This revealed further response categories, including Unmet Needs, where participants felt they should have been asked about DFV concerns because they were relevant to them but were not screened by staff for this issue. Also raised was the practice of Indirect Inquiry where questions were received that touched on issues that relate to DFV, such as behaviours and situations, rather than explicitly screening for DFV. Some reported Therapeutic Interventions that assisted with their situations, including social work sessions and specific psychological therapy techniques. Finally, several people provided information indicating they had No Present Needs in the area of DFV support or assistance.

They were very concerned and assisted me with strategies and resources to manage the situation.

I have felt very supported by staff members and been given encouragement to speak my truth.

When asked if the staff member who received the disclosure provided the assistance they found helpful (Survey Question 7), 85.71% responded Yes (n = 12), and 14.29% responded No (n = 2). No participants were Unsure. Five disclosing participants also provided text-box information for this question (Table 5). Qualitative content analysis indicated that disclosing participants had felt Empowered about their situations and encouraged to be assertive about their needs, including pursuing justice. Active Support was also described as assisting with the transition home and ongoing assistance. Therapeutic Interventions were also again described as useful, across a range of interventions, including social work support, family counselling and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS).

| Participant response | Response category |

|---|---|

|

Active support |

|

Therapeutic interventions |

|

Therapeutic interventions |

|

Empowered |

|

Empowered |

The final quantitative survey question asked participants if they had ever wanted to disclose information about experiencing DFV to a staff member at the Health Service but did not feel comfortable to do so (Survey Question 8). A total of eight participants (13.11%) responded Yes to this question, 78.69% responded No (n = 48) and 8.2% were Unsure (n = 5). Six of the participants who answered Yes were of female gender identity and age in the 20–29 years (1), 30–39 years (2), 50–59 years (1) and 60–69 years (2) age brackets. The remaining two participants who responded Yes were male and in the 20–29 years and 40–49 years age brackets. Of the participants who responded Yes to this questions, four had never disclosed DFV to the health service on any occasion (as per their responses to Question 3) and a further one was unsure if they had disclosed (totalling 62.5%). Further analysis indicated that three of the participants who had wanted to disclose information, but did not feel comfortable to do so, had never been screened for any type of DFV concerns on any encounter/occasion at the health service (see Figure 1 for a Venn diagram illustrating group numbers around screening and disclosure).

Data S2 documents the text-box responses provided by participants when asked about wanting to disclose, but not feeling comfortable to do so. Qualitative descriptive and content analysis revealed some new categories, including that respondents were at times Selective in Disclosure showing a preference for certain clinicians in their treating team (including doctors/psychiatrists, registrars and nurses). Support and Comfort were mentioned by a number of participants, both in regard to facilitating disclosures, but also as general appreciation for the clinical care provided. Lack of Follow-up was also described, with one respondent indicating that they had disclosed in a session with two doctors present (psychiatrist and registrar), but that the subject was never raised with them again. Missed Opportunity was also raised, with one client indicating that they would have disclosed, had they been asked. Finally, the Historical nature of many of the DFV episodes (e.g., occurring in childhood or with previous intimate partners) influenced whether participants felt that it was relevant to disclose these experiences or not.

Over a quarter of females (27%) and one in nine males (11%) had disclosed DFV concerns, while a further 9% of women, and 6% of men, had wanted to disclose, but had not felt comfortable to do so. This bought the total proportion of the respondents in the study with DFV concerns to 31% (19/62), including 36% of females and 18% of males, with no concerns raised by the sole non-binary respondent.

Finally, respondents were given the opportunity to provide any further information they chose, about the health service's response in assisting with DFV issues, in open text-box format. These results are provided in Data S3, with 21 responses received. In these responses, a number of issues detailed in earlier text-box responses were also raised here, including Nature and Type of Family Violence, Therapeutic Interventions, No Present Needs, Support and Comfort, Missed Opportunities and the Historical nature of DFV experiences. Qualitative descriptive and content analysis also revealed a number of additional important premises. These included Family Violence as Reason for Admission with one respondent indicating they had been admitted during a crisis, while leaving an abusive situation. This respondent also indicated that they Viewed the Hospital as a Safe Place to come and receive support for their DFV situation. Another stated they perceived that DFV Law Changes impacted positively on the way services responded and gave a voice to women and families experiencing violence. Several indicated that DFV issues should be given a Higher Profile at the service, with another stating it was an important topic. One response appeared to endorse Direct, Clear Enquiry (‘Just ask the question’), while another pointed to Bias with Screening as they felt they had not be asked about DFV, due to their demographic characteristics (middle aged, male). Safety Planning was also raised. Finally, several respondents suggested 1:1 Psychology Support should be more readily available. One respondent wished that they had been referred to a psychologist after their disclosure. Another indicated they felt they could not raise the issue or disclose it in therapy groups, as it would be too triggering for other clients, but that they would have appreciated individual, trauma-focussed psychological therapeutic intervention.

5 Discussion

The current study sought to characterise client perceptions of DFV screening in a private mental health service and explore areas of unmet need. Objective one of this study was met, with the results providing information about DFV screening and the clinical response to disclosures, from a client perspective, at a private, inpatient mental healthcare service. Meeting objective two, the study results indicated one-third of the cohort had not been screened for family violence (to their recall). This occurs despite mental health difficulties being a central indicator that screening should occur in best-practice guidelines (The Royal Women's Hospital 2018; Safe and Equal 2023). As such, the far majority, if not all, clients presenting with mental health difficulties are likely to meet the recommended requirements for screening. Findings are in keeping with previous research which has identified relatively low rates of screening in mental health settings more broadly (Fisher, Hebel, et al. 2023; Gillespie et al. 2023).

The results also indicated that spontaneous disclosure of DFV concerns did not occur in the absence of screening. These results link in with previous research indicating that direct asking about DFV by health professionals is important as is the need to persist in asking over time (Spangaro, Zwi, and Poulos 2011). Qualitative investigations indicate that clients need to feel trust in the service, and the professional making the enquiry, before a disclosure will occur (Spangaro et al. 2011). Numerous factors can act as barriers for mental health service users to disclose. These include a failure of professionals to notice the signs of abuse, fear the disclosure will not be believed, and concern about blaming attitudes (Rose et al. 2011).

Unmet DFV needs were identified in 13% of the cohort, falling within the 9%–20% range identified in other public adult medical and mental healthcare studies in the state (Fisher, Galbraith, et al. 2020; Fisher, Rudkin, et al. 2020; Fisher, Rushan, et al. 2023; Fisher, Troy, et al. 2023). This finding addresses objective three of the study. This result, in combination with the qualitative findings, indicates that service-wide whole-of-hospital improvements to screening and response practices are needed, to ensure all clients are screened, and so that screening is done in a manner that promotes trust and safety, to increase the comfort of clients to disclose, should they want to.

When considering all participants with family violence concerns (both disclosing and non-disclosing), twice as many female participants had concerns, relative to their male counterparts. This is consistent with Australian population-based trends with females reporting considerably higher rates of DFV experiences, relative to males (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2019). A similar discrepancy has also been found in international studies (Kernsmith 2006; Stewart, MacMillan, and Kimber 2021). Women who experience DFV may have higher levels of post-traumatic stress, depression and anxiety, relative to male victim-survivors, along with a higher likelihood of having sexual abuse, stalking and coercive control perpetrated against them (Caldwell, Swan, and Woodbrown 2012). Women also tend to be more afraid of the person using violence against them (Caldwell et al. 2012), which may result in a chronicity of mental health distress, increasing both the need for, and likelihood of, an admission for mental health treatment. Given these factors, it is not surprising that female victim-survivors seek mental health care at high rates. Sixty percent of Portuguese female victim-survivors reported seeking mental healthcare assistance, with 40% receiving specialist mental health care, most commonly delivered by a psychiatrist (Ugnė Grigaitė et al. 2024).

To our knowledge, this is the only study that has investigated rates of DFV concerns in a cohort made up solely of private inpatient mental healthcare consumers. The findings indicate that people from higher socio-economic brackets (i.e., those who have the means to fund private health insurance) experience DFV at similar rates to those reported by public mental healthcare consumers from the same geographic region (Fisher, Hebel, et al. 2023). This differs to some degree from other research that has compared women using antenatal services as public versus private health patients. A North American study found that 11% of public patients reported experiencing intimate partner abuse during their pregnancy, compared to 2% of patients with private health insurance (Kearney et al. 2003).

While DFV screening rates, as determined by consumer reports, were suboptimal in this study, responses indicated that the majority of people who had disclosed felt supported by the staff member they disclosed to, and that they were provided with the assistance they found helpful. Qualitative responses also indicated that a number of consumers found staff supportive and comforting, and that therapeutic interventions (with a variety described) were helpful. Further, one respondent indicated that they had sought an inpatient admission at the hospital specifically to remove themselves from a DFV situation, and did so because they perceived they would receive good care and assistance with their situation. Both the model of care, and quality of the care, are likely to have contributed to this result. Clients had access to 30 min of one-on-one nursing input, every day-time shift, access, via referral, to a variety of allied health disciplines (including psychology and social work), and most clients were reviewed by their treating psychiatrist at least twice per week. Further, the vast majority of clients admitted to the hospital, have single (non-shared) rooms, throughout their stay, which contributed to feelings of privacy and safety.

The quantitative and qualitative results also indicated a number of areas in which improvements in DFV screening and response are needed. This included screening all clients who attended the service, regardless of age or gender identity. Clinician responses to disclosures could be further improved, through both active follow-up and offering consumers the opportunity to address DFV issues with a clinician in a confidential one-on-one setting, with psychology support, specifically, requested by respondents. Safety planning should also be implemented as part of the disclosure response, in all situations where there is a current risk of harm the DFV situation.

The mixed methods approach to this research represents an important study strength. The quantitative data allowed for the establishment of rates, types and timing of screening as well as rates of disclosure and unmet needs, as reported by client respondents. Qualitative data allowed participants to provide further information, in their own words, and revealed a number of important premises, across questions. These included factors affecting their ability or choice to disclose DFV, including systemic barriers, feeling more comfortable with specific clinicians, whether the abuse was historical in nature, and whether or not clients were actually screened. A number of positive outcomes of disclosure were indicated, including receiving support and comfort from clinicians, being provided with therapeutic interventions they found helpful and feeling empowered in the management of their situation. The text-box responses also further confirmed that missed opportunity, through lack of screening, directly impacts on whether clients disclose, and that some male service users attribute not being screened to their demographic.

A number of limitations of this study should be noted. Firstly, the pen-and-paper administration method of the survey impacted the quality of the data collected. It resulted in missing data (3% item non-response) with a number of respondents completing the survey, but not providing responses on items, throughout. Had the survey been administered via electronic means (such as via IPad) or via emailed link or QR code, administration software could have prompted respondents to fill in missed items, before allowing them to move on to the next question—reducing rates of accidental non-response. It is also possible that pencil-and-paper administration resulted in a mild suppression of disclosure. Clients may have perceived, in needing to hand the paper survey back to the clinician–researcher (after completing it independently in their hospital room), that their responses would identify them as having DFV issues, despite no direct personal identifiers being collected (name, date of birth, hospital number and address). The disclosure of sensitive behaviours has been found to be higher in electronic surveys compared to paper-based survey administration (Gnambs and Kaspar 2014). It is possible that this effect also extends to the disclosure of sensitive experiences or concerns, such as DFV.

Other potential limitations are the sample size and the sample being taken from a single private mental-health inpatient facility. Further, only one respondent identified as having a non-binary gender identity. No respondents identified as being transgender or chose the Other gender option. Thus, the results cannot be considered representative of people who are transgender, non-binary or gender-diverse.

Finally, the survey tool utilised was tailored towards gaining information about screening and support for victim-survivors of DFV. The context information provided at the start of the survey (see Data S1) anchors respondents to think about their (potential) experiences as a recipient of DFV behaviours, rather than as someone who uses (i.e., perpetrates) these types of behaviour. As such, it possible that survey respondents only considered their DFV concerns from a recipient of violence perspective, rather than as a user of violence. Because of this, the quantitative and qualitative data obtained is not likely to incorporate or reflect concerns or issues of clients of the service who may be using violence against family members. Notably, no respondents provided qualitative information that described concerns about using violence as part of their own behaviour. This supports the likelihood that this was uncaptured, by the data set.

Domestic and family violence conveys a range of significant psychological and mental health consequences. The current research study indicates that DFV experiences and concerns, in Australian inpatient private mental health service users, may be as prevalent as those experienced by public mental health service users. Of importance, screening for DFV concerns appears to have a direct relationship with the likelihood of disclosure, with no unscreened service users reporting making disclosures. For those clients who had disclosed, the utility of a supportive response, and capacity to also access therapeutic mental health interventions, was greatly appreciated. Universal DFV screening, in combination with a supportive and informed response, should be standard practice across all types of mental health services, due to the high prevalence of needs within mental health service users, and the opportunity to provide meaningful assistance.

It is recommended that DFV training for mental health nurses uses both the LIVES framework (World Health Organization 2014), discussed above, and the method of sensitive enquiry (The Royal Women's Hospital 2018; Fisher, Rushan, et al. 2022, 2023; Fisher, Troy, et al. 2023). The latter involves a six-step process. These include (1) Notice the signs—identify when patients may be experiencing family violence using evidence-based risk factors and behavioural and emotional symptoms; (2) Enquire sensitively—screen for family violence experiences in a confidential environment that promotes trust; (3) Respond respectfully—provide a supportive, non-judgemental response, that allows the client to explain their situation, in their own words; (4) Risk identification—utilise existing screening tools appropriate to region/service/area to assist in identifying any high-risk factors in the patients situation; (5) Assistance—offer support options, promote choice, make on-referrals to specialist internal and/or external services, complete safety planning; (6) Documentation—clear and secure method that documents issues discussed, and the risk screening, safety planning and referral to follow-up services. These evidence-based frameworks have been designed to improve identification, appropriate supportive responses, enhance safety and promote patient autonomy and choice.

The current project was conducted as part of the initial stages of a transformational change project in DFV clinical response at the participating mental health hospital site. The next stage of the project has commenced and involves comprehensive training of DFV clinical champions, and then rolling out generalised training to all clinical and support staff, throughout the service. This training is based on LIVES and sensitive enquiry frameworks and incorporates teaching in the states' DFV risk assessment tool (State of Victoria 2021). As part of this initiative improvements in the utilisation of referrals to both the social work and psychology services for clients with DFV needs, as well as housing transition assistance, will be reinforced.

5.1 Relevance for Clinical Practice

Screening for family violence is an important part of clinical practice in mental health care, regardless of the setting in which the service is provided. Clients' value enquiry in this area when a supportive and helpful response is provided to disclosures. This research indicates that a failure to screen clients can result in a missed opportunity to assist with needs in this area, particularly as spontaneous disclosures in the absence of screening are uncommon.

Acknowledgements

The study authors would like to thank the client participants. Open access publishing facilitated by La Trobe University, as part of the Wiley - La Trobe University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Melbourne Clinic Research Ethics Committee (Project Number: 339).

Consent

As per ethics approval consent was implied upon informed agreement to participate.

Conflicts of Interest

The first three authors were salaried employees at the health service at the time of the study. The fourth author was on training placement. There are no other relationships that may pose a conflict of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.