Re-Examining the Predictive Validity and Establishing Risk Levels for the Dynamic Appraisal of Situational Aggression: Youth Version

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

The Dynamic Appraisal of Situational Aggression: Youth Version (DASA:YV) is a brief instrument, most often used by nurses and was specifically designed to assess risk of imminent violence in youth settings. To date, it has been recommended that DASA:YV scores are interpreted in a linear manner, with high scores indicating a greater level of risk and therefore need more assertive and immediate intervention. This study re-analyses an existing data set using contemporary robust data analytic procedures to examine the predictive validity of the DASA:YV, and to determine appropriate risk bands. Mixed effect logistic regression models were used to determine whether the DASA:YV predicted aggression when the observations are correlated. Two approaches were employed to identify and test novel DASA:YV risk bands, where (1) three risk bands as previously generated for the adult DASA were used as a starting point to consider recategorising the DASA:YV into three risk bands, and (2) using a decision tree analysis method known as Chi-square automated interaction detection to produce risk bands. There was no statistically significant difference between a four and three category of risk band. AUC values were 0.85 for the four- and three-category options. A three-category approach is recommended for the DASA:YV. The new risk bands may assist nursing staff by providing more accurate categorisation of risk state. Identification of escalation in risk state may prompt early intervention, which may also prevent reliance on the use of restrictive practices when young people are at risk of acting aggressively.

1 Introduction

Violent behaviour by young people in mental health inpatient settings is common, threatening the physical and psychological well-being of staff and other young people in care (Dean et al. 2010; Tremmery et al. 2012). Violence adversely impacts unit atmosphere, creates fear and undermines routines; as such, it lessens a unit's potential to assist recovery and rehabilitation. Violence also contributes to financial costs through property damage and staff absences (Daffern et al. 2015; Edward et al. 2016). Staff experiences of victimisation may compromise care; staff, particularly nursing staff, who are often tasked with preventing and managing aggression must de-escalate, contain and settle aggressive young people in the least restrictive manner, which may be difficult when they are fearful or distressed by recent exposure to violence. Care and safety of the unit can be difficult to balance in practice (McKenna and Sweetman 2021).

1.1 Background

Restrictive practices that are used to prevent a young person from acting violently or to contain a young person whilst they are harming others can be detrimental, and there is worldwide recognition of the need to reduce, and where possible, eliminate these practices (Department of Health 2013; McKenna 2016). There are; however, inherent challenges to reducing the use of these strategies, and nurses have expressed fear and concern about their elimination, highlighting the need for guidance on alternatives to ensure the safety of staff, people in care and visitors (Lantta et al. 2016; Muir-Cochrane, O'Kane, and Oster 2018).

Violence risk assessment is a critical precondition to violence prevention. Risk assessment is designed to identify patients at elevated risk, prompting staff to implement early and less restrictive methods to prevent violence (Griffith et al. 2021; Maguire et al. 2019). Multiple personal, environmental and interactional (person by environment) factors contribute to violence within mental health settings. Identifying and considering the multitude of factors in the risk assessment and determining their relative weight is complicated and time-consuming. This is a particular challenge in mental health units because the environment is dynamic and violence risk fluctuates. These fluctuations necessitate repeated reappraisals. Monitoring risk state and identifying those people whose risk is escalating encourages early intervention, potentially lessening the use of restrictive practices to prevent violence. Careful monitoring of risk state should also result in a corresponding relaxation of unnecessary restrictions when the level of risk is tolerable (Carroll and McSherry 2018).

If repeated assessment is required to capture fluctuations in risk state, then it is important that methods used to appraise risk are reliable, brief and easy to use. Whilst some research provides support for the use of unstructured clinical assessments in the appraisal of violence in inpatient settings for both adults (McNiel and Binder 1994; Nijman et al. 2002) and youth (Phillips, Stargatt, and Brown 2012), the broader literature is unequivocal that structured instruments have superior predictive accuracy. The Dynamic Appraisal of Situational Aggression: Youth Version (DASA:YV; Daffern et al. 2008) and the Brief Rating of Aggression by Children and Adolescents (BRACHA; Barzman et al. 2011) are the only brief instruments specifically designed to assess risk for imminent violence in youth settings. The Brief Rating of Aggression by Children and Adolescents (BRACHA) was not designed for use once a young person is admitted to a mental health unit, nor has it been validated to repeatedly assess risk state.

1.2 The Dynamic Appraisal of Situational Aggression: Youth Version (DASA:YV)

DASA:YV is a brief actuarial scale derived from the adult version, the Dynamic Appraisal of Situational Aggression (DASA; Ogloff and Daffern 2006). It includes 11 items: negative attitudes, impulsivity; irritability, verbal threats, sensitivity to perceived provocation, easily angered when requests are denied, unwillingness to follow directions, anxious or fearful, low empathy/remorse, significant peer rejection and outside stressors (Daffern et al. 2008). The last four items are youth-specific and were derived, with permission from the Structured Assessment of Violence Risk in Youth (SAVRY; Borum, Bartel, and Forth 2003). DASA:YV items seek to capture risk state; they do not provide comprehensive information about other personal, environmental and interactional variables that might provide a foundation for a formulation of the young person, which may be necessary for treatment planning and long-term risk management. Rather, the DASA:YV was designed to assist nurses to identify a violence risk state associated with an increased risk for imminent (within the next 24 h) violence and who may therefore benefit from support and intervention, addressing the factors that are contributing to their risk. There is evidence that supports the DASA:YV having a moderate ability to predict violence within that 24 h period (Koh et al. 2020). Time of completion of the DASA and DASA:YV is generally determined by the unit and local practice needs, for example in the service where the DASA was developed the DASA is completed at midday, so the DASA rating can be handed over to the next shift along with plans for intervention.

Three studies examining the predictive validity of the DASA:YV exist, with the ages of young people in the samples ranging from 6 to 21 years (Chu et al. 2012; Dutch and Patil 2019; Kasinathan et al. 2015). The predictive validity of DASA:YV has been found to vary between studies (AUC = 0.59–0.90) (Chu et al. 2012; Dutch and Patil 2019; Kasinathan et al. 2015), and between male and female youth (Chu et al. 2012). Chu et al. (2012) investigated the DASA:YV with 49 young people (29 males, 20 females) aged 12–18 years old who were detained in two high-security youth correctional institutions in Singapore. Results showed the DASA:YV total score significantly predicted any aggressive episode, including interpersonal violence, within the subsequent 24 and 48 h. The AUC values for ‘any aggression’ over the subsequent 24 h (AUC = 0.59) and 48 h (AUC = 0.57) were poor to moderate. Examination of male and female subsamples showed the DASA:YV total scores were predictive of aggression for males but not for females.

Kasinathan et al. (2015) examined the validity of the DASA:YV with a sample of 35 young people (34 male, 1 female) hospitalised in an adolescent forensic mental health unit. The young people in this sample ranged in age from 14 to 21 years, with 43% identifying as First Nations people. The results demonstrated statistically significant AUC values ranging from 0.72 (physical aggression towards others) to 0.75 (any type of aggression). The authors concluded that the DASA:YV was reliable in the assessment of imminent aggression and that the DASA:YV performed marginally better than the adult version of the DASA.

Dutch and Patil (2019) examined the predictive validity of the DASA:YV with a sample (n = 103) of male and female youth aged 6–18 years residing in an Australian locked acute care inpatient mental health unit. Results showed good interrater reliability (overall κ-value of 0.79) (Landis and Koch 1977) and statistically significant predictive validity with AUC values ranging from 0.84 (physical aggression against other people) to 0.92 (verbal aggression against other people), with an AUC value of 0.90 for any aggression in the subsequent 24 h. Dutch and Patil (2019) concluded the DASA:YV to be a valid and reliable instrument in the assessment of imminent aggression with a youth population.

Despite these positive findings, there has been criticism expressed about the statistical techniques that have been used to analyse the type of longitudinal data that are typically acquired in violence risk assessment studies, including those involving short-term risk assessment instruments (see e.g. Coid et al. 2015). Recent studies with the adult DASA have used data analytic procedures that can account for the clustering that occurs in repeated measurement data (Griffith et al. 2021; Maguire et al. 2017), but this has not yet been done with DASA:YV. Another critical need is to establishing risk bands (i.e. scores that equate with a low, moderate and high risk of imminent violence) for DASA:YV. Thus far, it has been recommended that DASA:YV scores are interpreted in a linear manner, with high scores indicating a greater level of risk and therefore need more assertive and immediate intervention. The adult DASA has risk bands (low, moderate and high), and recent studies using the adult DASA with risk bands linked to violence prevention strategies indicated by an Aggression Prevention Protocol (Maguire et al. 2018) have shown how risk bands and associated recommendations can produce reductions in aggression and a lessening of restrictive interventions by structuring nursing intervention. This study seeks to re-analyse an existing data set (Kasinathan et al. 2015) using contemporary robust data analytic procedures to examine the predictive validity of the DASA:YV, and to determine risk bands.

2 Methods

Results for this study have been reported using the Risk Assessment Guidelines for the Evaluation of Efficacy (RAGEE) (Singh, Yang, and Mulvey 2015).

2.1 Setting and Participants

This study used data established and described by Kasinathan et al. (2015). The study setting was a six-bed adolescent forensic mental health unit providing acute care and rehabilitation to adolescents within the Forensic Hospital (a 135-bed high-security mental health hospital) in Sydney, Australia. Participants included 35 patients (n = 34 male and n = 1 female patient) from 14 to 21 years of age. Approximately half were First Nation Australian peoples (n = 15; 43%). Data were collected between March 2011 and November 2013. During this period, there was a total of 35 adolescents admitted to the hospital, and only one female, hence the reason for only one female in the sample. Diagnoses were determined using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association 2000). Most (n = 33; 94%) were diagnosed with a mental illness, whilst two (6%) had conduct disorder only: schizophrenia spectrum disorder (n = 29; 83%) was the most common diagnosis, n = 4 (11%) young people were diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and n = 31 (89%) were diagnosed with conduct disorder. During the study, two of the young people (6%) were transferred to rehabilitation units within the Forensic Hospital, and n = 27 (77%) were discharged to the community or youth custody.

2.2 Procedure

Trained nurses used DASA:YV to rate each young person daily. Additionally, nurses rated their final judgement of imminent aggression (final risk rating) as low, medium, or high following their completion of DASA based on their overall clinical judgement. Nursing staff were not instructed to intervene in any extraordinary way following DASA:YV assessment, other than adhering to practice as usual. At the time of the DASA:YV assessment, nurses also recorded whether the young person had acted aggressively during the preceding 24 h, using the following categories: any aggression, physical aggression towards others, verbal aggression and physical aggression towards objects. Each day's DASA:YV and final risk rating were then matched with the subsequent day's recording of aggression to examine predictive validity.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

2.3.1 Outcome Variable—Aggressive Behaviour

The main outcome of whether or not each young person engaged in any aggressive behaviour in the 24 h after each DASA:YV assessment was treated as a binary variable (any = 1, no = 0). Due to the nature of the data collected (repeated measurements of the DASA:YV for 35 patients for 90 consecutive days), mixed effect logistic regression models were considered appropriate to determine whether the DASA:YV predicted aggression when the observations are correlated. A mixed effect logistic regression is a statistical technique that can take in to account the dependency of the observations (Fitzmaurice, Laird, and Ware 2011; Twisk 2013), which in this present study are the repeated DASA:YV assessments of the young people included in the study. Odds ratios (OR) were used to determine the likelihood that patients would be aggressive depending on DASA:YV scores. This analysis was conducted using the DASA score of 0 as the reference group (Maguire et al. 2017); therefore, the odds of being aggressive in each of the DASA bands are compared with the odds of those who scored a DASA of 0. For example, the odds of someone in the moderate DASA band is compared with the odds of those in the DASA low band being aggressive.

2.3.2 Predictor Variables DASA-YV Risk Bands

The predictors examined in this study consisted of the total scores of the DASA:YV, a range of novel DASA:YV risk bands and aggression. Two approaches were employed to identify and test novel DASA:YV risk bands.

2.3.2.1 Approach 1—Low, Medium, and High-risk Bands

The first approach was based on work by Maguire et al. (2017) where three risk bands were generated for the adult DASA: 0—low risk, 1–3—moderate risk and 4–7—high risk. The justification for testing these risk bands was that previous research has validated these bands and seven of the 11 items in the DASA and included in the DASA:YV. Hence, there was reason to expect the same risk bands would predict aggression in the youth version. Using this as a starting point, we considered recategorising the DASA:YV (Scale 0–11) into three risk bands as: (low—0) (medium—1–3) (high—4–11).

2.3.2.2 Approach 2—Decision Tree Analysis

We also considered whether other possible risk bands might be appropriate for organising total scores on the DASA-YV into risk bands. In this second approach, we used a decision tree analysis method known as Chi-square automated interaction detection (CHAID) to produce risk bands.

‘CHAID is a recursive partitioning algorithm that searches for an optimal decision tree structure based on the correspondence between the dependent/response variable and a set of independent/splitting variables. It is part prediction, part clustering estimation command that seeks to reduce uncertainty about the values of independent/predict a response variable but simultaneously partitions the dataset into clusters of observations based on the set of splitting variables’ (Luchman 2013).

Decision tree analysis suggested four risk categories, 0—low, 1–3—medium, and 4–8—high risk, and 9–11—very high risk.

2.4 ROC Analysis

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to determine which approach was a better fitting model. To compare the difference between the areas under the two independent curves, we performed a comparison test, which can test equality of ROC areas. We also compared the curves visually by overlaying the ROC graphs.

2.5 Sensitivity Analysis

Like the approach adopted by Maguire et al. (2017), the focus of the predictive modelling was data for 90 consecutive days of the DASA:YV. To determine the possible impacts on the predictive modelling by restricting the data set to 90 consecutive days, we conducted a sensitivity analysis. We included data from patients who had more than 90 days of DASA records and outcome measures. See the Data S2 for results of this sensitivity analysis.

2.6 Power and Sample Size Calculation and Statistical Analyses

Since this was a secondary data analysis, we first conducted a post hoc power and sample size calculation to determine whether our sample would have enough predictive power and validity for our modelling. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata MP version 18 (Stata USA), where a 5% level of significance and 95% confidence interval (CI) were employed for all the analyses.

2.7 Ethics Considerations

This study was approved by the Justice Health and Forensic Mental Health (the Network) Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC). Project number: HREC: G655/22.

3 Results

3.1 DASA:YV Ratings

A total of 2037 DASA:YV ratings were completed. Total scores ranged from 0 to 11, the mean rating was 0.65 (SD, 1.6), and the median was 0. Ratings were skewed (3.04). In total, 78% of DASA: YV ratings were scored as 0; 7.2% were scored as 1; 4.0% were scored as 2; 3.1% were scored as 3; 2.5% were scored as 4; 1.5% were scored as 5; 1.2% were scored as 6; 0.8% were scored as 7; and 1.0% were scored as 8 or higher.

3.2 Aggressive Behaviour

There were 195 incidents of aggression in the study period: 49 episodes of physical aggression to others, 153 episodes of verbal aggression and 113 episodes of aggression towards objects.

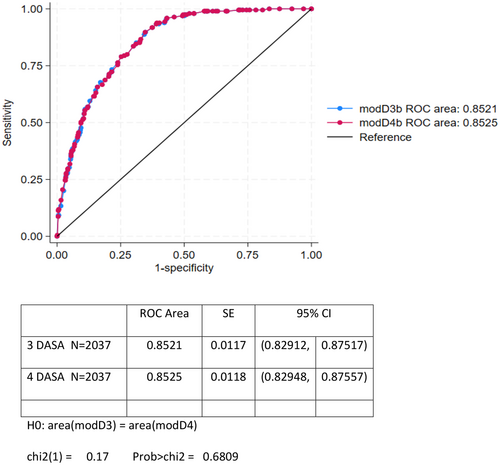

3.3 Roc Curve Analysis—Comparison of 3 Risk Bands vs 4 Risk Bands

Figure 1 shows a comparison of the two ROC curves for the DASA three (AUC = 0.8521) and DASA four (AUC = 0.8525) risk band categories; note that the three-category band was 0—low, 1–3—moderate and 4–11—high risk bands; the 4 band category was 0—low, 1–3—moderate and 4–8—high risk, and 9–11—very high risk. There was no statistically significant difference (nor visual differences) between the two categories of risk bands (X2 = 0.17, 1df p = 0.6809).

3.4 Odds Ratios for DASA:YV Risk Bands

Since there was no statistically significant difference between the two models (three and four risk categories) and their ROC curves, the three risk bands: DASA 0—low, DASA 1–3—moderate and DASA 4–11—high was retained as this was the simplest approach and consistent with the risk bands for the adult DASA, thereby reducing confusion. Using a mixed effect logistic regression, the OR for aggression increased corresponding to the increased risk; DASA 1–3, OR = 1.983 (95% CI; 1.112, 3.537), for DASA scores of 4–11, OR 4.543 (95% CI; 2.834, 7.284) (Tables 1 and 2).

| Outcome = Any aggression | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | Estimated proportions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DASA_Cat3:DASA 0 (Ref) | 1.00 | 0.068 | ||

| DASA 1–3 | 1.98 | (1.11, 3.54) | 0.0204 | 0.116 |

| DASA 4–11 | 4.54 | (2.83, 7.28) | <0.0001 | 0.203 |

| Constant | 0.04 | (0.02, 0.07) | <0.0001 | |

| RE Patient variance (_cons) | 1.83 |

| Outcome = Any aggression | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | Estimated proportions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DASA 0 (Ref) | 1.00 | 0.068 | ||

| DASA 1–3 | 2.00 | (1.12, 3.55) | 0.019 | 0.116 |

| DASA 4–8 | 4.29 | (2.55, 7.19) | <0.0001 | 0.196 |

| DASA 9–11 | 9.73 | (2.52, 37.57) | 0.001 | 0.314 |

| Constant | 0.04 | (0.02, 0.07) | <0.0001 | |

| RE patient variance (_cons) | 1.82 |

4 Discussion

Interpretation of DASA:YV scores prior to this study was based on an assumption of linearity between the total score and likelihood of aggression. For unit staff, this meant the higher the score the more assertively and immediately they should intervene. This study sought to establish risk bands that may assist unit staff interpret DASA:YV scores, communicate their risk assessment using widely used nomenclature and encourage appropriate targeted intervention. There was no statistically significant difference between four and three categories of risk band. AUC values were 0.85 for the four- and three-category options. As such, we recommend the three-category approach.

The new DASA:YV risk bands may assist nurses working in youth mental health settings by providing more accurate categorisations of risk state. Identification of escalation in risk state may prompt early intervention, which may prevent reliance on the use of restrictive practices when young people begin acting aggressively. Low DASA risk band ratings should also encourage a lessening of restrictions. Although there is no aggression prevention protocol like the one linked to the adult DASA (Maguire et al. 2019), these interventions may be worth testing to enhance nursing intervention. Two principles underpin Maguire and colleagues' Aggression Prevention Protocol, (1) nursing interventions should be matched to risk level, and (2) nursing interventions for those people at low risk should be the least restrictive, whereas more restrictive interventions (such as close observations, use of extra medication and limit setting) should be reserved for people in a higher risk state (Maguire et al. 2019).

Concerning limitations, this study was based on retrospective data and the unit where the study was conducted was a small specialised forensic adolescent mental health unit, which may impact generalisability. The cohort of patients in this study is predominantly male, so we were unable to explore whether there was a difference in predictive validity between males and females in this study. Another limitation of this study was that the sensitivity (See Data S2) for both models (3 classes and 4 classes) was relatively (to specificity) low. Although there were proportionately more people who were aggressive as the risk band increased (from low to high), there was still a larger number of people who were not aggressive in each risk band. This means that even though an increased DASA: YV score is associated with a greater risk of aggression, many people will not be aggressive even when they are assessed as moderate or high risk.

5 Conclusion

Results suggests strong predictive validity for the DASA:YV. A three-category risk band solution, equivalent to that used for the adult DASA, had almost identical predictive validity to a four-category solution derived from decision tree analysis. These risk bands may be used to more effectively communicate risk level and to create a foundation for development of a structured nursing aggression prevention protocol linked to risk level. This is a focus of our ongoing work.

6 Relevance to Clinical Practice

It is important that young people who are assessed as low risk are not subject to unnecessary restrictions, so as not to cause frustration and infringe upon their autonomy. Where possible, nursing interventions should be collaborative and engage with young person to understand their needs and personal concerns whilst maximising safety for other young people, staff and visitors and preventing the young person from acting aggressively, which may undermine their long-term interests.

Author Contributions

All authors listed meet the authorship criteria according to the latest guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, and all authors are in agreement with the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

Michael Daffern is a co-author of the Dynamic Appraisal of Situational Aggression: Youth Version (DASA:YV). The DASA:YV manuals is sold by the Centre for Forensic Behavioural Science (CFBS). Profit from these sales are held in a CFBS account and used to support DASA research.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.