Measurement of Psychological Resilience to Support Therapy Interventions for Clients in the Clinical Mental Healthcare Setting: A Scoping Review

Funding: This study was funded by the Australian Government's contribution to the recipient of an RTP Scholarship and supported by the University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia.

ABSTRACT

Waves of psychological research over 50 years have resulted in the development of scales to measure psychological resilience. Multiple psychological resilience definitions and factors have emerged during this time, making its measurement complex. The overall aim of the review was to identify and describe developments in the measurement of psychological resilience in the clinical mental healthcare setting. Specific objectives included (1) consideration of the validity and reliability of psychological resilience scales, (2) the effectiveness of the scales in clinical mental healthcare settings and (3) to identify the scope that resilience factors are addressed in the included scales. It provides a timely update regarding psychological resilience measurement tools and considers further developments that may be required. Between 2011 and 2024, databases were searched, and English-language, peer-reviewed papers with full text were extracted. Eligible studies were those reporting validated existing resilience measures or the outcomes of new measures for use in clinical mental healthcare settings. Seventeen studies met the inclusion criteria. The review demonstrated that psychological resilience measures require further development, particularly focusing on the utility of measurement tools in clinical mental healthcare settings. In this review, we highlight an existing gap in resilience measurement and underscore the need for a new measure of psychological resilience that can effectively assess individuals' subjective experience of their psychological resilience in clinical mental healthcare settings. The currently available psychological resilience measures included in this review do not directly reflect all the factors that might impact a client's depression or anxiety and warrant further research.

1 Introduction

Over more than five decades, extensive research investigating psychological resilience has evolved through many waves or shifts in psychological resilience research (Ungar and Liebenberg 2011; Terrana and Al-Delaimy 2023; Fletcher and Sarkar 2013; Masten and Narayan 2012). In conjunction with these waves, multiple definitions of resilience emerged and were accompanied by psychometric (measurement) scales designed to find psychological resilience factors (Windle, Bennett, and Noyes 2011). As a result, a comprehensive understanding of psychological resilience has progressively emerged, with recent studies emphasising the impact of depression and anxiety on psychological resilience (To et al. 2022).

In this scoping review, the term psychological resilience will refer to personal or individual resilience. The review also refers to clinical mental healthcare settings, which describe all health or mental healthcare settings where therapy for mental illness is provided. Many of the psychological resilience measures in this review are described differently as scales, measures and instruments. However, they are measures of psychological resilience completed by clients and may be described as patient-reported outcome measures (PROM). Clients is the term used to define individuals who receive mental health services.

The first concepts of psychological resilience emphasised risk and protective factors as explanations to describe how individuals bounce back from adversity (Masten and Narayan 2012). The second shift in psychological resilience understanding replaced this outdated explanation of psychological resilience. The second shift identified psychological resilience as a dynamic and multifaceted process (Terrana and Al-Delaimy 2023). The third shift focused on promotive and protective factors and processes, and the fourth and current shift considered the importance of the person's context. These waves overlap and add to a deeper understanding of the complexity of psychological resilience. As the waves in psychological resilience changed, they influenced the way measures of psychological resilience were designed. Nevertheless, over time, these psychological resilience measures have not been without criticism.

Windle, Bennett, and Noyes (2011) reported a review of psychological resilience measures. They determined that measuring psychological resilience in therapy settings posed difficulties due to the absence of a reliable measure specifically designed for that setting. Windle, Bennett, and Noyes (2011) reported that a few measures were subjected to a rigorous quality assessment. The psychological resilience measures were based on population studies and used classical test theory (CTT). The PROMs they included in their methodological review were in the early stages of development and lacked repeated validation studies, limiting their applicability in therapy.

Ungar and Liebenberg (2011) approached the issues in psychological resilience measurement differently, arguing that mixed methods led to a better understanding of the unique experience of psychological resilience following adversity. Terrana and Al-Delaimy (2023) continued highlighting the need for mixed-method studies. Many scales developed to measure psychological resilience have not considered cross-cultural and contextual sensitivities that influence unique expressions of psychological resilience.

To fully understand psychological resilience, a middle ground between group measurement that standardises scales using CTT and self-report measures that accommodate the individual's context needs to be developed (Terrana and Al-Delaimy 2023). New assessment scales need to be self-report measures, and qualitative data must be used more effectively when attempting to understand the individual. Mixed method approaches to accommodate the influence that the context makes on psychological resilience have been suggested as a way forward (Terrana and Al-Delaimy 2023).

When considering the specific context of individuals, recent research recognised the relationship between anxiety, depression and psychological resilience (Barzilay et al. 2020; Leys et al. 2020). The recognition of a relationship between depression and anxiety and resilience is not new. However, these studies examined the individual's context and psychological resilience using separate standardised measures. Measures included standardised resilience measures and standardised depression and anxiety measures (Barzilay et al. 2020). Correlations between these measures underpinned the significant relationship between depression, anxiety and psychological resilience.

The impact of adversity on psychological resilience and the development of depression and anxiety was identified during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 (To et al. 2022). According to the World Health Organization (World Health Organization 2022; GA Collaborators 2023), >5% of the worldwide population experiences depression and anxiety. The impact of COVID-19 led to a 25% increase in the prevalence of reduced psychological resilience, resulting in a mental health crisis due to overwhelmed healthcare services. In the aftermath of adversity, individuals commonly exhibit a decline in mental well-being, experiencing symptoms of depression and anxiety and potentially losing their sense of psychological resilience (Fossion et al. 2013; Leys et al. 2020).

Standardised psychological resilience measurement scales have continued to be used in population studies with groups of individuals to ascertain common factors contributing to psychological resilience. These studies suggest that a standard set of factors contribute to psychological resilience. However, when the identified factors found in quantitative measures of psychological resilience were added to factors of psychological resilience found in qualitative studies, the list of factors was numerous (Ungar, Ghazinour, and Richter 2013). Terrana and Al-Delaimy (2023) agreed with Ungar and Theron (2020), suggesting that qualitative findings regarding psychological resilience need to be used to change direction and provide respect for a person's subjective experience.

Improvements in psychological resilience and finding a middle ground that includes a person's context and lived experience should not be overlooked. One such context is the clinical mental healthcare setting. The significance of assessing psychological resilience within this setting cannot be underestimated, particularly considering the recent statistics (GA Collaborators 2023).

Masten and Narayan (2012) emphasised that psychological resilience is crucial in attaining self-mastery over adversity, encompassing various factors such as emotions, thoughts, social interactions and self-support. Enhancing individuals' capacity to stay motivated, cultivate self-mastery and navigate challenging circumstances would restore their psychological resilience. Given the well-established connection between depression, anxiety and psychological resilience, it would be practical to assess unique subjective psychological resilience within the therapeutic context to observe and facilitate changes in mental health directly. Ideally, the assessment would employ a dedicated instrument designed to evaluate unique changes in psychological resilience, delve into underlying emotional factors and encompass a comprehensive range of environmental information, including social and cultural impacts.

2 Background

The concept of psychological resilience remains ambiguous (Shean 2015). The American Psychological Association's (APA) Dictionary of Psychology (2022) defines psychological resilience as a process and outcome of successful adaptation to challenging life experiences. This adaptation is achieved through the flexible adjustment of mental, emotional and behavioural responses to internal and external demands. However, a standard view of psychological resilience is the ability to bend or bounce back from adversity (Harpaz-Rotem et al. 2014). This simplistic explanation fails to capture the complexity of psychological resilience or the individual psychological changes that occur following traumatic events. These two explanations of psychological resilience emphasise the significant variations in the definitions of psychological resilience, particularly within the context of personal adversity (Fletcher and Sarkar 2013).

In the clinical mental healthcare setting, an individual's unique experience of changes in psychological resilience is observable (Barzilay et al. 2020). Depression and anxiety may arise in individuals who experience a loss of resilience or struggle to cope with adversity (Robinson, Larson, and Cahill 2014; Waugh and Koster 2015). However, existing measures used to assess depression and anxiety symptoms in clinical mental healthcare settings, such as the depression, anxiety and stress scale (DASS) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), do not directly capture the multiple factors associated with psychological resilience (Beck, Steer, and Garbin 1988; Lovibond and Lovibond 1995). Currently, the association between depression, anxiety and psychological resilience is investigated using population-based studies that correlate psychological resilience measures with measures of depression, anxiety or stress (Ruiz-Parraga and Lopez-Martinez 2014).

The last review of psychological resilience measures was completed by Windle, Bennett, and Noyes (2011). Since that time, measures of psychological resilience highlighted by that review have been used in further validation studies with international populations (Sharif-Nia et al. 2024).The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) is the most widely used measure. However, the Sharif-Nia et al. (2024) systematic review indicated that the CD-RISC fails to account for personal perceptions of psychological resilience or the context of individuals and has errors in measurement.

This scoping review updates the work of Windle, Bennett, and Noyes (2011), but also considers the need for changes in the design and measurement of psychological resilience. This review aims to identify evidence of change in the psychological resilience scale approach and to further validate those scales and their utility in the clinical mental healthcare setting. This review wanted to find if a gap exists between how psychological resilience is currently measured and how it could be measured to account for subjective perceptions of psychological resilience in the mental healthcare context.

- Have changes in measurement techniques of psychological resilience occurred over the last 12 years since the review conducted by Windle, Bennett, and Noyes (2011)?

- How effective are the current and new psychological resilience measures in clinical mental healthcare settings?

- Do the existing psychological resilience factors identified in the current psychological measurement scales reflect the same elements of psychological resilience as posited in theories of resilience?

3 Method

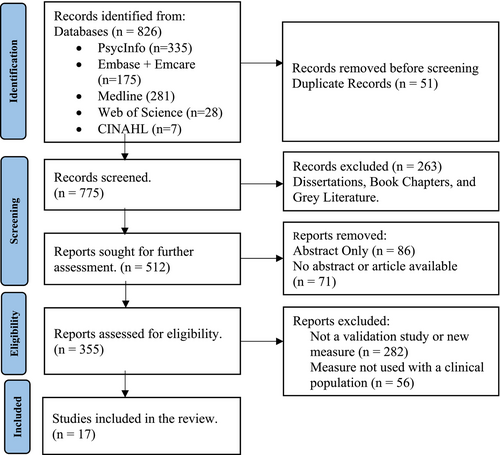

After identifying the research questions, this scoping review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) and the framework for scoping reviews (Sarkis-Onofre et al. 2021; Peters et al. 2020; Levac, Colquhoun, and O'Brien 2010). The population, content and context (PCC) framework (Pollock et al. 2023) guided the search strategy's development and the selection of the included studies. After the relevant studies were selected, data were charted, and the results were reported (Figure 1).

3.1 Search Strategy Identifying Relevant Studies

This review was registered with the Open Science Framework (OSF—https://osf.io/jyvmx). The search strategy located published, peer-reviewed studies using psychological resilience measures in clinical and mental healthcare settings. Multiple databases were searched for relevant studies, including the Ovid database (PsycInfo, AMED, Medline, Embase, Emcare and Joanna Briggs), Web of Science and CINAHL.

The research team discussed and refined the search terms used in the review. The search strategy was conducted on three occasions in September 2015, January 2022 and May 2024 to identify new or recently validated PROMs within published papers. Boolean search terms were used to locate relevant literature: ‘resilience’, ‘resilience’ and ‘psychological’ OR ‘Test’ OR ‘reliability’ OR ‘psychometrics’ OR ‘measurement’ OR ‘factor structure’, OR ‘validity’, OR ‘rating scales’, OR ‘confirmatory factor analysis’, OR ‘test construction’, OR ‘validation’. Also, ‘psychological resilience’ AND ‘Test’ OR ‘reliability’, OR ‘psychometrics’, OR ‘measurement’, OR ‘factor structure’, OR ‘validity’, OR ‘rating scales’, OR ‘confirmatory factor analysis’, OR ‘test construction’, OR ‘validation’.

Following the search, data management was supported using Endnote Version 21.3 (The Endnote Team 2024). All identified citations were collated and uploaded into Endnote. Abstracts were assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the PCC of interest. Potentially relevant full-text studies were retained.

3.2 Inclusion Criteria

The sourced articles were written in English and peer-reviewed, with full text available from 2011 to May 2024. This period was selected because Windle, Bennett, and Noyes (2011) published a comprehensive methodological review that focused on all psychological resilience measures developed before 2011.

3.3 Exclusion Criteria

Articles published before 2011 and/or in a language other than English and articles published after 2011 that did not validate or develop a psychological resilience scale were also excluded, as were studies that had not used or validated a psychological resilience scale in a clinically derived population. Research studies using psychological resilience scales in business, sports or school settings were also excluded.

3.4 Population

Studies of interest included people of any age with chronic health and/or mental health conditions who might be clients in a clinical healthcare or mental healthcare setting. These groups encompass participants ranging in age from children, adolescents through to older adults and clients with various health or mental health conditions. The included studies were required to assess the participants using a psychological resilience measure in these settings (see Table 1).

| Author, year and title | Purpose | Target populations | Measurement scale, completion mode and format | Results | Recommendation | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development of a multi-dimensional measure of resilience in adolescents: the Adolescent Resilience Questionnaire (Gartland et al. 2011) | To develop a resilience measure for Adolescents |

Secondary school adolescents without illness. Adolescents with chronic illness Study One n = 330 Study Two n = 451 |

Adolescent Resilience Questionnaire | This measure could differentiate between populations of adolescents with personal characteristics showing positive engagement. Some scales are not supported by statistical analysis | Further psychometric testing is required | Construct validity needs further consideration. Test–retest, criterion validity and sensitivity need to be investigated further |

| Validation of the Suicide Resilience Inventory-25 (SRI-25) in adolescent psychiatric inpatient sample (Gutierrez et al. 2012) | Confirmatory Factor Analysis of original scale SRI Scale (Osman et al. 2004) |

Psychiatric Inpatient Adolescents n = 204 |

Suicide Resiliency Inventory (SRI-25) Self-Report 25 Items Likert Scale |

This measure could differentiate between youth with suicide ideation and those without suicide ideation Underscores the importance of addressing individual unique factors, described as internal well-being |

Additional research is needed |

Pain influencers were not considered Not generalisable Self-report instrument |

| Resilience in family caregivers of persons with acquired brain injury (Las Hayas, Lopez de Arroyabe, and Calvete 2015) | Examination of primary caregivers in Spain who care for a person with an Acquired Brain Injury | Resilience questionnaire for use with Caregivers of Acquired Brain Injury (QRC-ABI) n = 237 |

Self-Report 17 Items. 5-point Likert Scale |

Achieved construct validity | Explore with other caregivers for other populations |

No comparison with well-established measures of resilience. The absence of similar studies limits the contrasting results Small sample size No causal relationship can be made |

| Measuring resilience after spinal cord injury: Development, validation and psychometric characteristics of the and short form (Victorson et al. 2015) |

Develop a resilience item bank and assessment tool. SCI-QOL Resilience Item Bank Developing a PROM |

Spinal Cord injury patients n = 717 |

SCI-QOL Resilience item bank and Short Form Self-report 21 Items |

Claims to be a valid instrument for use in the clinical/clinical healthcare settings/therapy setting | Future use to evaluate outcomes and impact on resilience in anxiety and depression | No mention of limitations |

| Development of the Multiple Sclerosis Resiliency Scale (Gromisch et al. 2018) | To develop the Multiple Sclerosis Resiliency Scale |

Participants with a confirmed diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis n = 932 |

Multiple Sclerosis Resiliency Scale Self-report 25 Items |

Found five factors and an inverse relationship between the scale and depression and anxiety | Follow-up studies are needed to confirm factor structure and reliability | External validity was compared with the Chinese Version of the Resilience Scale. Participants needed to use computers. Diagnoses were self-reported with no prior confirmation of diagnosis |

| The Dyadic Communicative Resilience Scale (DCRS): Scale development, reliability and validity (Chernichky-Karcher, Venetis, and Lillie 2019) | To develop, test and validate a new resilience measure related to communication styles between cancer patients and their partners |

Cancer Patients n = 584 |

Dyadic Communicative Scale (DCRS) | The instrument found a two-factor structure, but the scale items did not capture the nuanced function of tension in couples | Future research could capture how participant characteristics contribute to resilience | Partners did not complete surveys. High correlations between subscales could be measuring the same constructs |

| Reliability and validity of the Multiple Sclerosis Resiliency Scale (MSRS) (Hughes et al. 2020) | To develop a Resilience Scale for patients with Multiple Sclerosis |

Patients with Multiple Sclerosis n = 216 |

Multiple Sclerosis Resiliency Scale (MSRS) |

Emotional and cognitive factors appear to contribute to resilience | Longitudinal in future research but clinical/clinical healthcare settings need patients to be considered | It is not an optimal tool for assessing high and low general resilience. Participants are primarily female and have low disability impacts |

| Factor Structure and Psychometric Properties of the Resilience Scale (RS) in a Spanish Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain Sample (Ruiz-Parraga, Lopez-Martinez, and Gomez-Perez 2012) | To provide data on the factor structure, reliability and validity of the Resilience Scale in a sample of Spanish chronic musculoskeletal pain clients |

Spanish Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain Patients n = 70 |

The Resilience Scale (RS) (Spanish Version). Self-Report 18 Items Likert Scale |

Valid Instrument. Is unidimensional in structure | Additional research needed |

Researchers noted that the measure was not generalisable; it was self-scored. They considered it should have been clinician-reported Pain intervention influencers are not considered |

| Resilience Scale-25 Spanish version: Validation and assessment in eating disorders (Las Hayas et al. 2014) | To validate and translate the Wagnall Young Resilience Scale—25 (RS-25) into Spanish |

Eating Disorder Cohort n = 46 |

Resilience Scale (RS-25) Spanish Version. Self-Report 25 Items |

Two-factor structure | Teach patients positive skills for intervention and management | Researchers considered the cross-sectional design and small participant numbers to have limited results. They were unable to assess whether tested qualities were present before the eating disorder developed |

| Validity and reliability of the Spanish version of the 10-item CD-RISC in patients with fibromyalgia (Notario-Pacheco et al. 2014) | To examine the validity of CD-RISC 10 in a Spanish population |

Spanish Fibromyalgia. Clients (Chronic Pain) n = 208 |

CD-RISC 10 (Spanish Version) Self-Report 10 Items Likert Scale |

Reported Scale as Reliable and Valid | Develop treatments to provide resilience | Influence of social desirability. Limited to the Fibromyalgia population |

| Resilience in organ transplantation: An application of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) with liver transplant candidates (Fernandez et al. 2015) | To find and assess the validity of the CD-RISC in liver transplant candidates |

Patients experiencing severe liver disease n = 120 |

CD-RISC Self-report 25 items Likert Scale |

Sample is too small for CFA or EFA | Longitudinal studies are required to find predictive validity. Might be useful in the clinical/clinical healthcare settings |

Sample from only one site Impact of possible social desirability |

| Measurement properties of the brief resilient coping scale in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus using Rasch analysis (López-Pina et al. 2016) | To test the reliability and validity of the BRCS |

Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus n = 232 |

Brief Resilient Coping Scale | Reliable and Valid using Rasch Analysis | Needs to be applied to other clinical/clinical healthcare settings samples | The length of scale is possibly too short. Requires clinicians to identify the degree of resilience |

| Reliability and Validity of the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) Spanish Version (Rodríguez-Rey, Alonso-Tapia, and Hernansaiz-Garrido 2016) | To explore the reliability and validity of the Brief Resilience Scale in the Spanish population |

Mixed multiple populations n = 620 |

Brief Resilience Scale 6 items Self-report Likert Scale |

Reliable and valid. Relationships between stress and resilience are complex. Treat results regarding age and gender with caution | Could be suitable in clinical/clinical healthcare settings and is the only suitable measure for Spanish populations | The sample may have been biased by the most motivated, who showed the most resilience. Bigger samples are required to test instruments. Researchers considered problems that existed with the population due to motivation determining resilience. Small sample size |

| Assessing health-related resiliency in HIV+ Latin women: Preliminary psychometric findings (Jimenez-Torres et al. 2017) | To validate the Spanish version of the Brief Resilience Scale |

Women with a diagnosis of HIV n = 45 |

Brief Resilience Scale Self-report 30 items |

Internal consistency and validity. Highlights the inverse relationship between psychological resilience and depression | Larger sample sizes and future studies are to be longitudinal | Small sample size and no temporal stability of measure |

| Measurement properties of the Nepali version of the Connor Davidson resilience scales in individuals with chronic pain (Sharma et al. 2018) | To develop and examine the CD-RISC-10 for use in Nepal |

Nepalese individuals with chronic pain n = 265 |

CD-RISC 10 10 items Self-Report Likert Scale and CD-RISC 2 2 items Self-report Likert Scale |

After translation results were consistent with one factor for CD-RISC 10. Reported similar findings to prior studies translating the CD-RISC10 | Future research needs to find a causal link between psychological functioning and resilience and identify minimal important change (MIC) statistics | Back translation is limited to one translator. Did not ask participants to rate changes in resilience. Limited time is allowed for time between the test and retest. Discreet test sample and did not assess MIC |

| Psychometric Assessment of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale for People with Lower Limb Amputation (LLA) (Miller et al. 2021) | To examine the CD-RISC 25 and CD-RISC10 |

Participants with LLA n = 122 |

CD-RISC 25 CD-RISC10 |

Floor and ceiling effects are considered acceptable Internally consistent and correlated to other disability measures |

Future research is needed to determine the significance of resilience in clinical/clinical healthcare settings and to inform interventions specifically targeting resilience characteristics |

Secondary analysis of previously collected data led to the exclusion of some variables Compromised sample |

| Psychometric Properties of the Persian version of the abridged Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale 10 (CD-RISC-10) among older adults (Rezaeipandari et al. 2022) | To prepare an abridged version of CD RISC 10 that is suitable for Persian populations |

Participants were Muslim and Zoroastrian, older adults with one to three simultaneous chronic diseases n = 400 |

Abridged CDRISC-10 | Good internal consistency test and retest reliability and a unidimensional scale | No criterion measure was used, which casts doubt on the results. There is limited generalisability due to different socioeconomic backgrounds, political disturbances and ethnicities | Further scrutiny and comparison with different Persian versions |

3.5 Concept

This review was interested in the number and type of factors that contribute to psychological resilience and how psychological resilience scales measure a clinical health or mental health population. The reliability and validity of psychological scales within clinical health or mental healthcare settings are considered essential to mental health outcomes (Windle 2015). The results, limitations and recommendations arising from the reviewed studies were considered regarding the usefulness of the current psychological resilience measures in the clinical setting.

3.6 Context

The intent of this review was to examine the utility and measurement of psychological resilience in clinical health or mental healthcare settings, so the selection of measurement studies was limited to these settings. Although the same scales are used in business, sports and school settings, these contexts are different from health and mental healthcare settings. These other settings would not offer any information regarding the use of psychological resilience in the context of health or mental health care.

3.7 Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

Patient Reported Outcome Measures are measurement scales increasingly used to assess individual outcomes in healthcare settings (Mokkink et al. 2010; Christensen et al. 2021). The COnsensus-based Standards for the Selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) analysis system was developed in an international Delphi study to evaluate the methodological quality of studies that measure the properties of a PROM (Prinsen et al. 2018). COSMIN analysis is a validated comprehensive strategy for assessing bias and the quality of psychometric measures used in healthcare settings (Mokkink et al. 2010).

The COSMIN Checklist sets out the criteria using a template of 10 boxes to assess the risks of bias and quality in measures. The first two boxes assess content validity and how well each item fits the population and the examined construct. Boxes three, four and five examine the structural validity, internal consistency and measurement variance. The final boxes, 6 through 10, are concerned with assessing responsiveness, reliability, measurement error and criterion validity. The COSMIN Risk of Bias Checklist also provides a scoring pattern that categorises the aspects of the study as very good (+), adequate (±), doubtful (−), inadequate (?) or not assessed (NA), which further describes the study. If a measurement scale was not specifically designed as a PROM, the COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist also provides a means of assessing the quality of other types of measurement studies (Mokkink, personal communication, April 2022). Each of the 17 studies in this review was examined using the COSMIN Checklist.

4 Results

The search strategy resulted in the identification of 826 records which were uploaded to Endnote. Following the removal of 51 duplicates, 775 records were screened. Of these 263 dissertations, book chapters and grey literature records were removed, leaving 512 records for further assessment. Eighty-six (86) abstracts and 71 reports for which no abstract or article could be located were also removed. A further 282 reports that did not include validation studies of psychological resilience measures or report the development of a new measure were also removed, as were 56 reports which did not involve the use of clinical populations. Seventeen remaining articles meeting inclusion criteria were included in the review and presented in the PRISMA flow chart (Sarkis-Onofre et al. 2021; Figure 1).

4.1 Characteristics of Included Studies

Have changes in measurement techniques of psychological resilience occurred over the last 12 years since the review conducted by Windle, Bennett, and Noyes (2011), and how effective are the current and new psychological resilience measures in clinical mental healthcare settings?

Among the 17 studies in this review, many authors made inferences about the utility of using their instrument in a clinical mental healthcare setting. The initial analysis of the included 17 articles revealed that current and new psychological resilience measures had various and significant limitations as reported by the authors. These limitations encompassed factors like small sample sizes or biased samples (Rodríguez-Rey, Alonso-Tapia, and Hernansaiz-Garrido 2016; Las Hayas et al. 2014; Las Hayas, Lopez de Arroyabe, and Calvete 2015), the omission of clinicians' reports (Ruiz-Parraga, Lopez-Martinez, and Gomez-Perez 2012) and issues related to construct validity (Gartland et al. 2011). The generalisability of the findings was also problematic (Gutierrez et al. 2012; Rezaeipandari et al. 2022). Victorson et al. (2015) emphasised the importance of consulting patients due to the identified relationship between depression and anxiety. Overall, participant characteristics, patient concerns and the importance of the clinical healthcare settings were underscored but not changed (Table 1).

4.2 Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

The first stage of assessment used the COSMIN Risk of Bias Assessment Tool (Mokkink et al. 2020). This assessment was discussed with the research team and completed by JM. In the second stage, the quality assessment of each scale using the COSMIN Checklist (Gagnier et al. 2021) was completed by JM and MH. The final stage involved all team members reaching a consensus (Table 2).

| Author, year and title | Scale name | Quality grade | Content validity | Structural validity | Internal consistency | Cross cultural validity | Reliability (test–retest) | Measurement error | Criterion validity | Hypothesis testing | Responsiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gartland et al. (2011).b Development of a multi-dimensional measure of resilience in adolescents: the Adolescent Resilience Questionnaire | Adolescent Resilience Questionnaire | Moderate | ? | ? | + | − | ± | ± | ? | + | ± |

| Gutierrez et al. (2012).b Validation of the Suicide Resilience Inventory-25 (SRI-25) in adolescent psychiatric inpatient samples | Suicide Resilience Scale | Moderate | ? | + | ? | − | ± | ± | ? | + | ± |

| Las Hayas, Lopez de Arroyabe, and Calvete (2015).b Resilience in family caregivers of persons with acquired brain injury | Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale | Moderate | ? | + | ? | − | ± | ± | ? | + | ± |

| Victorson et al. (2015).b Measuring resilience after spinal cord injury: Development, validation and psychometric characteristics of the SCI-QOL Resilience item bank and short form | Spinal Cord Injury-quality of Life (SCI-QOL) Resilience item bank. Short Form (IRT Study) | Moderate | + | + | ? | − | ± | ± | ? | + | ± |

| Jimenez-Torres et al. (2017).b Assessing health-related resiliency in HIV+ Latin women: Preliminary psychometric findings | Health Related Resilience | Low | ± | ? | − | − | ± | ± | ? | + | ± |

| Gromisch et al. (2018).b Development of the Multiple Sclerosis Resilience Scale | Multiple Sclerosis (MS) Resiliency Scale | Moderate | ± | ? | + | − | ± | ± | ? | + | ± |

| Chernichky-Karcher, Venetis, and Lillie (2019).b The Dyadic Communicative Resilience Scale (DCRS): scale development, reliability and validity | Development of the Dyadic Communicative Resilience Scale DCRS | Moderate | ± | + | ? | − | ± | ± | ? | + | ± |

| Hughes et al. (2020).b Reliability and validity of the Multiple Sclerosis Resiliency Scale (MSRS) | Multiple Sclerosis Resiliency Scale (MSRS) | Moderate | ? | ? | + | − | ± | ± | ? | + | ± |

| Ruiz-Parraga, Lopez-Martinez, and Gomez-Perez (2012).a Factor Structure and Psychometric Properties of the of the Resilience Scale in a Spanish Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain Sample | Resilience Scale | Moderate | ? | ? | + | − | ± | ± | ? | + | ± |

|

Notario-Pacheco et al. (2014).a Validity and reliability of the Spanish version of the 10-item CD-RISC in patients with fibromyalgia |

Spanish version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) | High | + | + | + | − | ± | ± | ? | + | ± |

| Las Hayas et al. (2014).a Resilience Scale-25 Spanish version: Validation and assessment in eating disorders | Spanish Version Resilience Scale—25 | Moderate | ? | ? | + | − | ± | ± | ? | + | ± |

| Fernandez et al. (2015).a Resilience in organ transplantation: An application of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) with liver transplant candidates | Connor Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) | Low | ? | ? | − | − | ± | ± | ? | + | ± |

| López-Pina et al. (2016).a Measurement properties of the brief resilient coping scale in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus using Rasch analysis | Brief Resilient Coping Scale (BRCS) using Rasch Analysis | High | ± | + | + | − | + | ± | ? | + | ± |

| Rodríguez-Rey, Alonso-Tapia, and Hernansaiz-Garrido (2016).a Reliability and Validity of the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) Spanish Version | Brief Resilient Coping Scale (BRCS) | Low | ? | + | − | − | ± | ± | ? | + | ± |

| Sharma et al. (2018).a Measurement properties of the Nepali version of the Connor Davidson resilience scales in individuals with chronic pain | Nepali Version Connor Davidson Resilience Scale | Low | ± | + | − | − | ± | ± | ? | + | ± |

| Miller et al. (2021).a Psychometric Assessment of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale for People with Lower Limb Amputation (LLA) | Connor Davidson Resilience Scale | Low | ? | ? | − | − | ± | ± | ? | + | ± |

| Rezaeipandari et al. (2022).b Psychometric Properties of the Persian version of abridged Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale 10 (CD-RISC-10) among older adults | Abridged Connor Davidson Resilience Scale | Low | ? | − | + | − | − | − | ? | − | ? |

- Note: Risk of Bias Assessment: (+) = very good, (±) = adequate, (−) = doubtful, (?) = inadequate, or NA = not assessed. Quality grade: high, moderate, low or very low.

- Abbreviations: CTT, psychological resilience scale developed in population study using Classical Test Theory; IRT, psychological resilience scale developed using Item Response Theory; RASCH Analysis, psychological resilience scale developed using Rasch Analysis.

- a Current = psychological resilience scale developed pre-Windle, Bennett, and Noyes (2011).

- b New = psychological resilience scale developed since Windle, Bennett, and Noyes (2011).

It is important to note that this grading is not an evaluation of the study but rather an assessment of its quality (Terwee et al. 2018).

4.3 Additional Assessments

JM conducted a further assessment of the psychological resilience measurement scales. The team then allocated factors in the psychological resilience scales to domains reflecting broad theoretical psychological resilience observations.

Regarding question three—Do the existing psychological resilience factors identified in the current psychological measurement scales reflect the same elements of psychological resilience as posited in theories of resilience? The findings indicated that several psychological resilience factors were identified in each of the 17 reviewed measures (Table 3). How these factors might relate to the elements of resilience is frequently discussed in the broad literature related to the construct of psychological resilience (McEwen 2016). Yet, when the research team examined 17 psychological resilience measures, it was difficult to determine how a clinician might use the factors to understand resilience. Of these 17 measures, 47% were unidimensional or mono-dimensional, meaning that factor analysis was impossible; 44% had achieved measured factors of psychological resilience (ranging from 2 to 7 factors). The remaining 8.5% of studies had either looked at dimensions but not reported factor analysis or had not performed any factor analysis. Possible domains of psychological resilience are drawn from the broad literature related to the construct of psychological resilience and presented below (Table 3).

| Author/s | Measure | Number of factors identified by the study | Allocation to possible domains | Self-care/determination (supportive self-beliefs) | Social support/connection to others | Emotional turmoil/affect/management | Executive functioning including cognitive skills |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gartland et al. (2011) | Development of a multi-dimensional measure of resilience in adolescents: the Adolescent Resilience Questionnaire | 5 | Yes | One factor | Four factors | ||

| Gutierrez et al. (2012) | Validation of the Suicide Resilience Inventory-25 (SRI-25) in adolescent psychiatric inpatient samples | 3 | Yes | One factor | One factor | One factor | |

| Las Hayas, Lopez de Arroyabe, and Calvete (2015) | Resilience in family caregivers of persons with acquired brain injury | 4 | Yes | Three factors | One factor | ||

| Victorson et al. (2015) | Measuring resilience after spinal cord injury: Development, validation and psychometric characteristics of the SCI-QOL Resilience item bank and short form |

5 One factor difficult to define as prior research refers to hardiness as resilience |

Yes | One factor | One factor | Two factors | |

| Jimenez-Torres et al. (2017) | Assessing health-related resiliency in HIV+ Latin women: Preliminary psychometric findings | Looked at dimensions but did not confirm factors | No but domains of social support, emotionality and executive functioning were considered | ||||

| Gromisch et al. (2018) | Development of the Multiple Sclerosis Resilience Scale |

5 One new factor concerning physical exercise and diet |

Yes | Three factors | One shared factor with cognitive functioning | Shared factor | |

| Chernichky-Karcher, Venetis, and Lillie (2019) | The Dyadic Communicative Resilience Scale (DCRS): scale development, reliability and validity | Seven factors | Yes | Five factors | One factor | Two factors | |

| Hughes et al. (2020) | Reliability and validity of the Multiple Sclerosis Resiliency Scale (MSRS) | 5 | Yes | Two factors | One shared factor with cognitive functioning | Shared factor | |

| Ruiz-Parraga, Lopez-Martinez, and Gomez-Perez (2012) | Factor Structure and Psychometric Properties of the Resilience Scale in a Spanish Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain Sample | Unidimensional | No | ||||

| Notario-Pacheco et al. (2014) | Validity and reliability of the Spanish version of the 10-item CD-RISC in patients with fibromyalgia | Unidimensional | No | ||||

| Las Hayas et al. (2014) | Resilience Scale-25 (RS) Spanish version: Validation and assessment in eating disorders | 2 | Yes | One factor | One factor | ||

| Fernandez et al. (2015) | Resilience in organ transplantation: An application of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) with liver transplant candidates | Unidimensional | No | ||||

| López-Pina et al. (2016) | Measurement properties of the brief resilient coping scale in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus using Rasch analysis | Unidimensional | No | ||||

| Rodríguez-Rey, Alonso-Tapia, and Hernansaiz-Garrido (2016) | Reliability and Validity of the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) Spanish Version | Mono-dimensional | No | ||||

| Sharma et al. (2018) | Measurement properties of the Nepali version of the Connor Davidson resilience scales in individuals with chronic pain | Unidimensional | No | ||||

| Miller et al. (2021) | Psychometric Assessment of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale for People with Lower Limb Amputation (LLA) | No CFA performed | No | ||||

| Rezaeipandari et al. (2022) | Psychometric Properties of the Persian version of abridged Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale 10 (CD-RISC-10) among older adults | Unidimensional | No |

- Abbreviations: CFA, confirmatory factor analysis; EFA, exploratory factor analysis; Mono-dimensional, psychological resilience measure does not consist of factors; Unidimensional, psychological resilience measure does not consist of factors.

5 Discussion

In 2011, Windle, Bennett and Noyes, conducted a review of psychological resilience measures. They determined that measuring psychological resilience in a therapy setting posed difficulties due to the absence of reliable measures specifically designed for that context. Windle, Bennett, and Noyes (2011) reported that several measures had been developed before 2011, but only a few successfully underwent a rigorous quality assessment process. Windle, Bennett, and Noyes (2011) also noted that many measures included in their review were still in the early stages of development and lacked repeated validation studies, limiting their applicability in a clinical mental healthcare setting.

The primary goal of this review was to address the findings of Windle, Bennett, and Noyes (2011) and determine if an instrument suitable for the clinical mental healthcare setting had been subsequently developed. The research considered any modifications made to psychological resilience measurement scales (used with clinical populations) over the past 12 years, along with the quality and validity of the measures. Our objectives also included identifying if a gap exists between the way factors of psychological resilience are measured in the general population and the way distinct aspects of unique individual and psychological resilience factors are measured in the therapy context.

The review posed three research questions. Have changes in measurement techniques of psychological resilience occurred over the last 12 years since the review conducted by Windle, Bennett, and Noyes (2011)? How effective are the current and new psychological resilience measures in clinical mental healthcare settings? Do the existing psychological resilience factors identified in the current psychological resilience measurement scales reflect the same psychological resilience elements as posited in psychological resilience theories?

The review found 17 psychological resilience measures used in populations with mental health concerns. The most frequently used psychological resilience measure was the CD-RISC, followed by the RS and the BRCS (Sinclair and Wallston 2004; Windle, Bennett, and Noyes 2011). These scales have undergone multiple evaluations in various populations, focusing on aspects including factor structure, validity, reliability, item fit and test–retest reliability (Gonzalez et al. 2015; Boone 2016). In the case of the RS, nine different measures had been modified. Some modifications were made to adapt the scale for use with different populations, such as older adults or adolescents, while others involved altering or reducing the number of items. The CD-RISC was also modified in the reviewed studies, and most recently, this scale was again abridged and modified for a Persian population (Rezaeipandari et al. 2022). Each psychological resilience measurement study provided varying arguments regarding the definitions of psychological resilience and the factors that contribute to psychological resilience.

This review did not find any significant changes in the studies. Test and retest reliability (Rezaeipandari et al. 2022), validity and reliability in several studies (Notario-Pacheco et al. 2014; López-Pina et al. 2016) failed to report minimal clinical important difference (MCID). The failure of the psychological resilience measures to report MCID continues to be concerning. This is important as MCID is considered important when measuring subjective change in therapy (McGlothlin and Lewis 2014). Although several studies claimed possible utility in clinical healthcare settings, consideration of the recommendations and limitations indicated that use of currently available instruments in these settings remains problematic.

These common psychological resilience measures employed CTT, generalising population information and adopting an objective approach to examining psychological resilience. Although these population-based studies have identified various psychological resilience factors, they have not observed individual-level changes in psychological resilience (Victorson et al. 2015). That is, they do not include the unique subjective experience of individuals experiencing mental health issues. Christensen et al. (2021) highlighted that modern test theory (MTT) might produce better outcomes in measuring psychological resilience. This suggests that using item response theory (IRT) or Rasch analysis (a form of IRT) when designing psychological resilience measures would offer more significant insights than CTT.

However, applying Rasch analysis to the most used scales would be problematic, as Resnick and Inguito (2011) pointed out, in examining the CD-RISC using Rasch analysis. Ceiling effects were observed in that study, and the scale required more challenging items to be added. With the BRCS, only four items on the scale limit its usefulness in clinical mental healthcare settings because the items would not sufficiently describe the client's experience (López-Pina et al. 2016).

The COSMIN guidelines showed that the quality of psychological resilience measures varied. Victorson et al. (2015) used IRT to examine participants and items, and López-Pina et al. (2016) used IRT to examine participants and items. López-Pina et al. (2016) used Rasch analysis and achieved a high-quality rating. Although most studies met the criteria outlined in the COSMIN risk of bias and quality assessment, only Notario-Pacheco et al. (2014) and López-Pina et al. (2016) showed high quality.

Previous studies and commonly used psychological resilience measures have faced criticism regarding the structure of factors and the validity of items and were not developed as PROMs for use in the clinical mental healthcare setting (Windle, Bennett, and Noyes 2011; Shean 2015). Terwee et al. (2018) state that a measure should not be classified as a PROM if it has been used in validation studies or randomised controlled trials involving population studies. Yet, the measurement studies reviewed had not specifically identified their study design as a PROM. Consequently, according to Terwee et al. (2018), no psychological resilience measure would qualify as a PROM.

Christensen et al. (2021) suggest that developing a PROM using IRT may be more appropriate when a subjective measure of psychological resilience is required. Christensen et al. (2021) argued that using psychological resilience scales without designing and validating them according to the COSMIN Analysis guidelines for PROMs would be unwise. Finally, the psychological resilience measures identified in this study do not directly assess depression or anxiety, nor do they directly seek self-reports of a person's unique psychological resilience (Christensen et al. 2021).

5.1 Feasibility of Using These Instruments in Clinical Mental Healthcare Settings

The concept of psychological resilience is multifaceted and lacks a universally agreed-upon definition (Fletcher and Sarkar 2013). Old definitions such as bounce back are likely very unhelpful to individuals receiving therapy for mental illness (Fisher and Jones 2023). Definitions of psychological resilience and issues with psychological resilience measures should not exclude the ongoing role of research in finding a measure of subjective psychological resilience.

Existing measures present limitations for the assessment of unique subjective psychological resilience (Sharif-Nia et al. 2024; Windle, Bennett, and Noyes 2011). In the clinical mental healthcare setting, the BRCS, for instance, consists of items designed for quick and easy use (López-Pina et al. 2016). However, too few items on the BRCS limits the clinician's ability to interpret these questions to target symptoms of mental health (Wagnild and Torma 2013). Resnick and Inguito (2011) conducted Rasch Analysis of the RS with older adults. They pointed out that while the scale may be useful in a clinical mental health care setting with an insufficient number of items and poor item fit the RS cannot differentiate older adults who were more resilient from those who are less resilient.

The association between depression, anxiety and psychological resilience is typically examined using population studies and neglects unique individual-level changes in subjective reports of psychological resilience (Terrana and Al-Delaimy 2023). Problems with psychological resilience measures potentially restrict therapists' ability to confidently assess psychological resilience changes as outcomes of therapy (Windle, Bennett, and Noyes 2011; López-Pina et al. 2016). Victorson et al. (2015) suggested that resilience instruments capable of assessing the relationship between depression, anxiety and resilience in clinical healthcare settings may offer better evaluations of subjective psychological resilience.

Finally, this review demonstrated the presence of a gap in knowledge between psychological resilience as measured by psychological resilience scales and the knowledge needed for clinicians to enable the measurement of psychological resilience for clients in the clinical mental healthcare setting.

Accordingly, we propose the development and implementation of psychological resilience measures that are designed specifically as PROMs. As an outcome of changing measurement from population studies to person-centred analysis, pre- and post-examinations of an individual's unique perception of their psychological resilience is possible.

5.2 Recommendations

- Develop and implement reliable measures of psychological resilience: It is recommended to invest in the development and validation of assessment tools that accurately measure psychological resilience in individuals experiencing the symptoms of depression and anxiety. Developing a PROM for clinical settings will provide a better understanding of the unique perceptions of psychological resilience. The measure should be sensitive enough to track unique perceptions of psychological resilience, detect MCID and changes over time and should be consistently useful in clinical mental healthcare settings.

- Conduct further research: Continued research is needed to better understand the relationship between psychological resilience, symptoms of depression and anxiety and effective treatment interventions. This research should focus on identifying evidence-based practices and interventions that enhance psychological resilience and improve mental health outcomes.

By implementing these recommendations, mental health clinicians can play a vital role in mitigating the impact of the high prevalence of depression and anxiety by promoting better outcomes in psychological resilience by targeting and monitoring effective treatments for individuals in need.

5.3 Limitations

The examination of psychological resilience measures was limited to clinical client populations that may reasonably be expected to be influenced by depression and anxiety. Other populations where depression and anxiety may be prevalent were excluded, as the subjects of these studies were recruited from non-clinical or business settings.

6 Conclusion

Findings of this scoping review indicated that despite numerous studies investigating and measuring psychological resilience, none have demonstrated their usefulness in the therapy setting thus far. Considering both the factors arising from psychological resilience measures and the additional elements of psychological resilience cited in the literature, a PROM for use in the clinical mental healthcare setting needs to be broad. The identification of factors like self-esteem, self-awareness and ability to make decisions, plan and focus on the future would likely offer clinicians more specific targets in therapy. The persistent absence of validated measures of psychological resilience suitable for clinical healthcare settings underscores an existing gap in the field, as originally identified by Windle, Bennett, and Noyes (2011). In addition, the review also identified that a middle ground, as suggested by Terrana and Al-Delaimy (2023), had not been considered. Consequently, there is a compelling argument for developing a novel measure that addresses the gap. Such a measure should not only possess practical value in clinical mental healthcare settings but also have the capability to assess individual differences in the various components that constitute unique perceptions of psychological resilience. Additionally, a novel resilience measure should also consider the symptoms of depression and anxiety, which previous research has suggested are integral to understanding the unique variations in psychological resilience factors.

Further research and development efforts should be directed towards the creation of an innovative measurement tool, such as a PROM that meets these criteria. Such a measure would greatly contribute to enhancing the effectiveness of therapy interventions by enabling the clinician to evaluate subjective psychological resilience factors comprehensively. This would facilitate the use of tailored treatments for individuals grappling with mental health challenges.

7 Relevance to Clinical Practice

In clinical practice, it is crucial for clinicians to accurately measure and understand the internal changes and symptoms experienced by individuals to effectively enhance their self-mastery following exposure to difficult circumstances. This process plays a vital role in refining therapy for individuals with depression and anxiety. However, this review revealed that the measures examined were not employed in clinical healthcare settings to evaluate unique subjective experiences of psychological resilience. Furthermore, the suitability of current and commonly used psychological resilience measures in clinical healthcare settings remains questionable. Given the absence of an appropriate measure for assessing psychological resilience in clinical mental healthcare settings, caution should be exercised when utilising existing and new psychological resilience measures. It is imperative for clinicians to be aware that these measures pertain to general factors of psychological resilience rather than capturing the unique intra-individual changes that influence subjective psychological resilience in specific clients.

Author Contributions

J.L.M., P.S., M.H., J.Y. and R.L.W. made substantial contributions to the concept development, research design, data analysis, writing of the manuscript and supervision of the project. JM wrote the main manuscript text, collected the data and managed the project. All authors have provided final approval of this version to be published.

Acknowledgements

This study forms a component of the requirements for the completion of a Doctor of Philosophy for J.L.M. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Newcastle, as part of the Wiley - The University of Newcastle agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Conflicts of Interest

Prof. Rhonda Wilson is an editorial Board Member of International Journal of Mental Health Nursing.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

We have included all data in our manuscript, so have none further to share.