Summarising Quantitative Outcomes in Parental Mental Illness Research

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

A quarter of all children grow up in a family where a parent experiences a mental illness (FaPMI). Research activity in this area is growing rapidly and it is now critical to better understand the extant knowledge in the field. This scoping review of quantitative FaPMI literature parallels a qualitative literature review and a series of Delphi studies with key stakeholders (e.g. lived experience and clinicians), that is part of a larger program of research to achieve consensus regarding the direction of FaPMI research; including making recommendations about outcomes and measures. The programme of research aims to promote and facilitate greater comparison and learning across studies and settings. Initially this scoping review summarises the quality and focus (e.g. country and sampling) of 50 quantitative studies from 2000 to 2023 and then classifies studies according to outcomes for parents, children and families. Six to eleven years were the most common child sample group and girls were slightly underrepresented (49/51) and parents were 88% mothers. Analogous parent and child outcomes were; mental illness/psychopathology, wellbeing, mental health literacy, trauma and stressful experiences, coping, help seeking/service need, within family relationships and supports, outside family relationships and supports. Additional outcomes for parents were; parenting skills, parent competence and parenting stress and for children in relation to their; cognitive functioning and caregiving. The family related outcomes were the within and outside family relationships and supports. Since 2000 there have been 136 different survey instruments employed with approximately 80% used in only one study. This suggests that the broader goals of the program of research are warranted as there is a need for less heterogeneity in measures used. Suggested areas for future research include a sampling focus on fathers, economic evaluations of programs, parent mental health literacy, trauma, genetics and integrating well-being concepts into research designs. Child research should focus on mental health literacy, the level and impact of caring responsibilities, assessing past trauma and the roles of close family and external supports.

1 Introduction

This century has seen a rapid increase in research regarding families where a parent has a mental health illness (FaPMI). Google Scholar searches using the term ‘Parental Mental Illness’ returned 150 results on the topic in 2000, 234 in 2005, 392 in 2010, 591 in 2015, and 800 in 2020. The research is important as it is estimated that 23% of children in the community have at least one parent who has experienced a mental health problem (Maybery, Reupert, Patrick, et al. 2009) and 36% of young people attending child and adolescent mental health services have a parent with a mental illness (Campbell et al. 2020). Equally, a similar number of people attending adult mental health services are parents (Ruud et al. 2019) and a recent study highlighted that 34% of such children were experiencing mental health symptoms in high-risk range (Nordh et al. 2022). It has also been shown that children of parents being treated by specialised psychiatric services are 2–13 times more likely to develop their own mental health problems (Gregersen et al. 2022; Lawrence, Murayama, and Creswell 2019), to be less school ready (Bell et al. 2019), to present with higher rates of physical injury, be more likely to be taken into care, and to develop health conditions such as asthma (Reupert et al. 2015). As recently highlighted by the Prato Research Collaborative for change in parent and child mental health (Reupert et al. 2021) FaPMI research has great potential to break the cycle of mental illness in families.

Given the gravity of the topic and rapid growth in research interest, it is important to understand the progression of FaPMI research with a view to providing future direction including making recommendations about outcome measurement. Thanhäuser et al. (2017), have highlighted the need for future research to include high quality research methods and designs and Elson et al. (2023) irreverently highlight that psychological measures are not toothbrushes—they can be used by more than one person, ‘Most psychological measures are used only once or twice. This proliferation and variability threaten the credibility of research’ (1). Dilemmas and debates around the identification and use of appropriate outcome measures span the mental health field for both clinicians and researchers. There is significant heterogeneity in terms of what is measured, the instruments used, and the purpose and goals of measurement—all of which can challenge the interpretation of research results and the effectiveness of clinical interventions (Chevance et al. 2020). Measures may focus on symptomology, quality of life, individual stress or coping, or broader elements of subjective well-being. They may be based on clinician, patient or child-reported outcomes or on patient-reported experiences. Measurements may be used to make diagnostic decisions, identify appropriate care pathways, gauge the effectiveness or acceptability of treatment, or to track changes in illness severity (e.g. Marriot, Sleed, and Dalzell 2019; Collins 2019; Khan and Tracy 2021). Critical reflection on the construction, scope and purpose of the measurement instruments used in the field is an important undertaking, without which there is the risk of undermining the validity of the conclusions drawn from their use (Flake and Fried 2020).

The complexity of conceptualising priorities and measuring outcomes is exacerbated by tensions experienced by some clinicians and service users between the goals of measuring rigorously-defined, medically significant outcomes, and the goals and desires of service users themselves for their own outcomes and recovery (Khan and Tracy 2021). Service users may be actively suspicious of, and opposed to, the perceived goals of outcome measurements that focus on ‘narrow clinical aspects of mental illness’ (Collins 2019, 4) rather than accounting for their own goals for recovery, empowerment and wellbeing. Over the past decade, mental health policies and practice environments have increasingly adopted a holistic perspective of recovery, complementing the biomedical model focused on reducing symptoms. The place of the family in the individual's recovery is increasingly recognised. Some authors underline the importance of relational recovery, which is described as a process that contributes to and is influenced by family life, family experiences and the well-being and functioning of other family members (e.g. Price-Robertson, Obradovic, and Morgan 2017). Thus, indicators of well-being and relational recovery should be examined in the future.

Identifying a set of core outcomes to be used consistently in research with FaPMI, and potentially in routine service delivery, enables direct comparison of outcomes across time, services and countries, and so increases opportunities to better understand an individual's experiences and the effectiveness of services. There are a number of international exemplars of approaches to implementing agreed outcome measures. An early example of a country-wide approach is Australia where the need for the routine assessment of outcomes in mental health services was identified in the National Mental Health Strategy in 1992. In 2003, the Australian Mental Health Outcomes and Classification Network (AMHOCN) was established to lead the implementation of the agreed outcome measures in routine practice (see https://www.amhocn.org/ accessed 18 October 23). They include mental health, social functioning and experience of services measures. Another example is the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) which was founded in 2012 and its aim is to define sets of patient-centred outcome measures to be used internationally. ICHOM's approach is to do this by health condition and so, within their work on mental health, there are already a number of recommended outcome sets, including for depression and anxiety; depression and anxiety for young people with eating disorders; and neurodevelopmental disorders (Obbarius et al. 2017; International Consortium on Health Outcome Measurement 2022).

There are challenges in identifying a core set of outcome measures in the FaPMI area. The first relates to the process of agreeing what outcomes are important. Opinions may vary within and between key stakeholders, including people using services, their families, service providers, researchers and policy makers (Collins 2019). The second is about how to organise the scope of an agreed set as it can be done in a variety of ways, for example, by a broad area such as AMHOCN at the mental health services level as in Australia, or by condition as with ICHOM. Even when it is possible to identify and agree on an outcome set, another issue may involve how reliably the measures are used. A further concern could be that having an agreed set, which is used across research studies and services, may narrow the focus of intervention and inhibit the development of hypotheses, service developments, research designs and even new outcome measures.

2 Aims

In response to the issues noted above, our research team undertook a scoping review of outcome measures in the FaPMI field. Scoping reviews have been noted as best serving research topics in which there is considerable complexity and heterogeneity in a field and the relevant literature has not previously, been comprehensively reviewed (Peters et al. 2020). This scoping review seeks to illustrate the quantitative outcomes used in FaPMI research. It is one component of a broader, international program of research seeking to determine and achieve a consensus on the most important research aims, outcomes and instruments to measure outcomes for families where a parent has a mental illness. A parallel review of the qualitative literature and a series of International Delphi studies with key stakeholders (e.g. lived experience young people, parents and mental health clinicians in the field) are also being undertaken to determine through consensus the direction for future research in this field. The findings from the quantitative and qualitative reviews will be combined with the first round of Delphi results and then presented back to key stakeholders to obtain recommendations regarding an outcome set.

- What is the focus and quality of quantitative FaPMI research?

- What outcomes have been measured in quantitative FaPMI research?

- What instruments have been used to measure outcomes?

- How can outcomes be categorised?

Together, the multi-study components will inform the aims of future research including making recommendations about the methods and instruments (e.g. questionnaires) to be used to measure outcomes.

3 Methods

3.1 Design of the Review

‘Scoping reviews are a method of knowledge synthesis that identify trends and gaps within an existent knowledge base, or scope of knowledge, for the purpose of informing research, policy, and practice’ (Westphaln et al. 2021, 2). The review was guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Reviewer's Manual on scoping reviews (Peters et al. 2020) was harmonised with the seminal work of Arksey and O'Malley (2005) first five scoping review stages; defining the research question/s, identify studies, selecting studies for inclusion including exclusion/inclusion criteria, sorting and categorising the data and summarising the results. The approach was also cognisant of modifications suggested to Arksey and O'Malley's approach by Daudt, van Mossel, and Scott (2013) and Westphaln et al. (2021). Arksey and O'Malley's sixth stage (consultation with stakeholders) will combine the current results with those from the Delphi study and qualitative scoping review findings.

3.2 Literature Search

Based upon the research questions and with the support of a specialist subject librarian, the search strategy used the following terms: ‘children of parents with a mental illness’ or ‘families where a parent has a mental illness’ or ‘parental mental illness’. The approach and syntax were adapted as necessary for each database. The databases that were searched were selected as the most relevant to this area of research: PsycInfo; Medline; and the International Bibliography of Social Sciences (IBSS). The searches were for title, abstracts and keywords. They were also limited to articles in English, as translation was not available to the team, and to articles from the year 2000, as research in this area has developed over that period. The initial searches were completed in July 2021 and then updated in May 2023 to identify any further relevant research in that period.

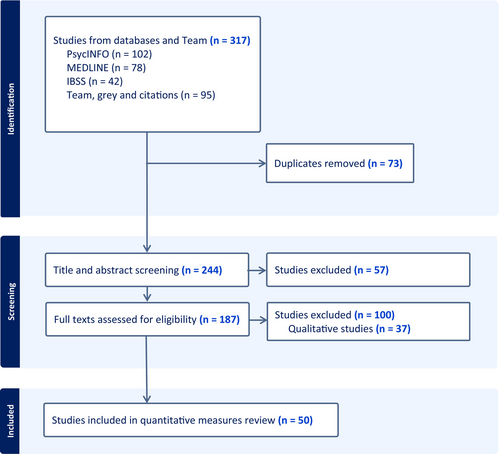

The initial search identified 175 results (PsycInfo 94, Medline 50 and IBSS 31) and the 2023 update identified a further 47 (PsycInfo 8, Medline 28 and IBSS 11). An additional 95 potentially relevant articles were identified by the research team so there was a total of 317 results. Duplicates (n = 73) were removed and 244 studies were then title-abstract screened.

Papers were included if they: (1) addressed outcomes of parent mental health for children and families, (2) studies were written in English in peer-reviewed journals and (3) studies were published in or after 2000. These results included quantitative, qualitative, review and data linkage papers—only the quantitative studies were included in this scoping review. Papers were excluded if: (1) they were qualitative, (2) literature reviews, (3) they addressed perinatal parent mental illness (as they involve different approaches to measurement such as observation of parent–child interactions), (4) they investigated parent–child prevalence estimates in mental health institutions (outside our focus; and there are already reviews on this literature), (5) were data linkage studies (e.g. outcome variables not established by the study authors) and (6) were editorial texts, commentaries or opinion papers.

A two-step screening process was used: (1) screening of titles and abstracts and (2) screening of full-text articles. Covidence, a web-based application for systematic reviews (Kellermeyer, Harnke, and Knight 2018), was used by two of the researchers to independently screen each abstract. A third reviewer was consulted to settle any disagreement regarding inclusion or exclusion of a document. Next, full-text screening of the identified records (n = 244) was undertaken independently by two researchers, with disagreements settled by a third researcher.

The PRISMA flowchart in Figure 1 shows that there were 244 papers in total after removing duplicates, 57 were excluded through the title and abstract screening, and a further 100 at the full-text stage. Of the remainder, 37 were qualitative and 50 quantitative, the latter were included for review in this paper.

3.3 Study Quality

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed by the second and third authors using the JBI critical appraisal checklist for quantitative research for each of the designs reviewed. The JBI is a widely used quality assessment tool for assessing quantitative papers (Porritt, Gomersall, and Lockwood 2014). The JBI checklist items were attributed binary outcomes, (Yes = 1, all other options = 0), resulting in a maximum total score of 13 for a Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) design, 11 for cohort, 9 for quasi experimental (QE) and 8 for cross sectional (CS). The total JBI score for all papers within a particular design was used to categorise the methodological quality as either ‘high’ (RCT = >10–13, Cohort = >8–11, quasi experimental >7–9, cross sectional >6–8), ‘moderate’ (RCT = 4–9, Cohort = 5–7, quasi experimental 4–6, cross sectional = 3–5) or ‘low’ (RCT = <4, Cohort = <4, quasi experimental <3, cross sectional = <2).

Thirty papers were deemed to be of high quality and 20 moderate. Detailed quality appraisal ratings are shown in Table 1. The 17 RCT studies generally reported rigorous analysis and presented in-depth descriptions of the methodological processes. Eight were high and nine were moderate quality. A significant limitation in many of the RCTs was that allocation to treatment groups was not concealed or was unclear and/or that participants were not blind to treatment assignment, nor were those delivering the treatment or assessing outcomes. Within the nine cohort studies, four were high and five of moderate quality. Significant limitations in several of the cohort studies were either that participants were not free of the outcome at the start of the study, or that there was insufficient information on follow-up (i.e. attrition, reasons to loss to follow-up). Within the 14 quasi-experimental studies, 10 were of high quality and four of moderate quality. The most significant limitation was the absence of a control group. In addition, it was unclear in seven studies whether participants in different groups were receiving similar treatment other than the intervention of interest. However, most of the quasi-experimental studies reported rigorous analysis and presented in-depth descriptions of the methodological processes. Within the 10 cross-sectional studies, eight were of high quality and two of moderate quality. None discussed strategies to deal with confounding factors.

| Study no. | Author/year | Country | Study design | Sample N and gender | Quality rating | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent N, % mothers | Child N, age mean (SD), % female | |||||

| 1 | Aylward and Sved Williams (2023) | Australia | QE | N = 493, 100% | N = 520, 9.1 (7.1), 47% | High |

| 2 | Beardslee et al. (2003) | U.S.A. | RCT | N = 190, 77% | N = 138, 11.6 (1.9), 42% | Moderate |

| 3 | Beardslee et al. (2007) | U.S.A. | RCT | N = 190, 77% | N = 138, 11.6 (1.9), 42% | Moderate |

| 4 | Bosch, van de Ven, and van Doesum (2020) | Netherlands | CS | N = 60, 81% | N = 79, 16.5 (2.9), 54% | High |

| 5 | Brandt et al. (2022) | Denmark | Cohort | N = 512, 7.8 (0.2), No gender | Moderate | |

| 6 | Chen et al. (2023) | China | CS |

Paternal parent N = 76, 24.3 (3.3), 47% Maternal parent N = 104, 24.3 (3.5), 58% |

High | |

| 7 | Cicchetti, Rogosch, and Toth (2000) | U.S.A. | RCT | N = 97, 100% | N = 158, 20.5 months (2.5), 49% | High |

| 8 | Clarke et al. (2001) | U.S.A. | RCT | N = 47, 78% | N = 47, 14.7 (1.5), 65% | High |

| 9 | Compas et al. (2010) | U.S.A. | RCT | N = 111, 86% | N = 155, 11.3 (2.1), 42% | High |

| 10 | Compas et al. (2009) | U.S.A. | RCT | N = 111, 86% | N = 155, 11.3 (2.1), 42% | High |

| 11 | Davies et al. (2022) | Australia | QE | N = 237, 11.1 (2.4), 51% | High | |

| 12 | Forman et al. (2007) | U.S.A. | RCT | N = 120, 100% | Moderate | |

| 13 | Foster et al. (2016) | Australia | QE | N = 64, 11.7 (2.5), 55% | Moderate | |

| 14 | Fraser and Pakenham (2008) | Australia | QE | N = 27, 13.4 (0.7), 59% | High | |

| 15 | Garber et al. (2009) | U.S.A. | RCT | N = 316, 14.8 (1.4), 58% | High | |

| 16 | Garosi et al. (2023) | France | Cohort | N = 724, 31.6 (9.4), 29% | Moderate | |

| 17 | Goodyear, Maybery, and Reupert (2005) | Australia | QE |

School holiday N = 31, 9.0 (nil), 77% After school N = 38, 9.4 (nil), 66% |

Moderate | |

| 18 | Havinga et al. (2018) | Netherlands | Cohort | N = 215, 18.9 (3.4), 72% | High | |

| 19 | Horowitz et al. (2001) | U.S.A. | RCT | N = 122, 100% | High | |

| 20 | Kallander et al. (2021) | Norway | CS | N = 238, 72.7% | N = 246, 12.4 (2.6), 57% | High |

| 21 | Liu et al. (2023) | Taiwan | CS | N = 33, 67% | High | |

| 22 | Lochner et al. (2021) | Germany | RCT | N = 100, 61.4% | N = 100, 11.89 (2.83), 53.5% | Moderate |

| 23 | Marston, Maybery, and Reupert (2014) | Australia | QE | N = 31, 87% | Moderate | |

| 24 | Mathai et al. (2008) | Australia | CS | N = 36, 7.9 (3.1), 57% | Moderate | |

| 25 | Maybery et al. (2022) | Australia | RCT | N = 41, 21.8 (2.2), 92.7% | Moderate | |

| 26 | Maybery, Reupert, Goodyear, et al. (2009) | Australia | CS |

Community N = 101, 9.7 (1.3), 52.5% Intervention N = 134, 9.0 (1.9), 44% |

Moderate | |

| 27 | Mechling (2015) | U.S.A. | CS | N = 120, 20.4 (nil), 81.7% | High | |

| 28 | Naughton et al. (2019) | Australia | Cohort | N = 134, 13.0 (3.5), 39.5% | Moderate | |

| 29 | Nicholson et al. (2009) | U.S.A. | QE | N = 22, 100% | High | |

| 30 | Nicholson et al. (2016) | U.S.A. | QE | N = 22, 100% | High | |

| 31 | Nordh et al. (2022) | Sweden | CS | N = 87, 11.9 (2.8), 41% | High | |

| 32 | Punamäki et al. (2013) | Finland | RCT | N = 119, 60% | Moderate | |

| 33 | Radicke et al. (2021) | Germany | QE | N = 134, 76% | N = 198, 12.2 (3.09), 56% | High |

| 34 | Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, van der Zanden, et al. (2022) | Netherlands | QE | N = 55, 14.1 (2.5), 38% | High | |

| 35 | Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, Weeland, et al. (2022) | Netherlands | QE |

Experimental N = 31, 13.9 (2.1), 39% Waitlist N = 24, 14.4 (2.9), 37% |

High | |

| 36 | Sanford et al. (2003) | U.S.A. | RCT | N = 44, 90% | Moderate | |

| 37 | Spang, Hagstrøm, et al. (2022) | Denmark | Cohort |

Parent Sch, N = 179, 7.8 (0.2), 45% Parent BP, N = 103, 7.9 (0.2), 43% Other illness, N = 183, 7.8 (0.2), 47% |

High | |

| 38 | Spang, Thorup, et al. (2022) | Denmark | Cohort | As above | Moderate | |

| 39 | Suess et al. (2022) | Germany | CS | N = 196, 75% | N = 290, 10.0 (SD = 4.0), 52% | High |

| 40 | Thorup et al. (2022) | Denmark | Cohort | N = 471, 7.0 (nil), 47% | High | |

| 41 | Valdez et al. (2011) | U.S.A. | QE | N = 17, 100% | N = 16 (9–16 years, no mean/gender) | Moderate |

| 42 | van der Zanden et al. (2010) | Netherlands | QE | N = 48, 85% | High | |

| 43 | van Loon et al. (2014) | Netherlands | CS | N = 124, 73% | N = 124, 13.4 (1.4), 51% | High |

| 44 | van Santvoort et al. (2014) | Netherlands | RCT |

Experimental N = 180, 10.4 (1.4), 64% Control N = 74, 10.0 (1.3), 59% |

High | |

| 45 | Veddum et al. (2023) | Denmark | Cohort |

Sch N = 113, 76% BP N = 80, 56% |

Parent Sch N = 147, 11.9 (0.3), 46% Parent BP N = 89, 11.9 (0.2), 46% |

Moderate |

| 46 | Verduyn et al. (2003) | United Kingdom | RCT |

CBT N = 47, 100% Group N = 44, 100% |

CBT N = 47, 38.1 (6.4) months, No gender Group N = 44, 36.4 (4.7) months, No gender |

High |

| 47 | Wansink et al. (2015) | Netherlands | RCT | N = 99, 96% | N = 99, 6.1 (2.0), 44% | Moderate |

| 48 | Wansink et al. (2016) | Netherlands | RCT | N = 99, 96% | N = 99, 6.1 (2.0), 44% | Moderate |

| 49 | Wirehag Nordh et al. (2023) | Sweden | QE | N = 86, 11.8 (2.8), 43% | High | |

| 50 | Zwicker et al. (2023) | Canada, United States, Netherlands, Australia | Cohort | N = 1884, 8 cohorts, ages 6–36 years, 48%–59% | High | |

3.4 Charting the Data

Table 1 also provides an initial summary of the authorship, countries and parent and child sampling of the 50 studies. We then undertook a process of synthesising and interpreting the outcomes employed in the studies according to the review research questions (Arksey and O'Malley 2005). Accordingly, we recorded and tabulated information from each paper regarding the outcome measure(s) used, how outcomes were defined and the purpose for which they were used. As each publication was tabulated, it became clear that studies could initially be grouped according to whether the measure focused on outcomes for the focal (a) parent, (b) children and young people or (c) families. This is reflected in the presentation of the data in Tables 2–4 corresponding to parent, young person and family outcomes. The initial data charting then extracted and presented from each study's methods section information regarding the outcome measure used (column 2), the purpose of the measurement and how it was defined (column 3) and any items or subscales employed (column 4).1 In addition, we extracted google scholar citations (GS cites – column 6) to outline the extent of use of each measure.

| Outcome concept | Instrument/informant | Purpose/definition | Items/subscales | Used by | GS cites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health/psycho-pathology | Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis and Melisaratos 1983) | ‘…self-report symptom inventory designed to assess the psychological symptom status of psychiatric and medical patients, as well as individuals who are not patients…brief form of the SCL-90-R.’ (Derogatis and Melisaratos 1983, 596) | 53 items reflect 9 primary psychological symptom dimensions and three global subscales of distress (General Severity Index, Positive Symptom Distress Index and the Positive Symptom Total. The 5-point scale of distress (0–4) from ‘not-at-all’ to ‘extremely’ (Derogatis and Melisaratos 1983) | 29, 30, 33, 34, 39 41, 44 | 49 800 |

| Beck Depression Inventory and Beck Depression Inventory-II (Beck et al. 1996) | ‘…to measure the severity of self-reported depression in adolescents and adults according to the DSM-IV….’ (Beck et al. 1996, 589) | Modifications from the original version – both include 21 items that participants respond to on 4-point scale from 0 to 3 (Beck et al. 1996) | 7, 9, 10, 19, 22, 46 | 394 000 | |

| Short-Form 36 and/or Health Survey SF-8 (Ware et al. 2001) | The 36 measures limitations due to mental or physical health problems (Valdez et al. 2011) | The SF36 measure limited physical, social, usual role, bodily pain, general mental health, emotional problems and vitality and the SF-8 is a short version of SF-36 and that includes four-item physical and four-item mental health component scales ‘…scored for the previous week on a five- or six-point scale.’ (Kallander et al. 2021, 408) | 4, 20, 29, 30 | 699 000 | |

| Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Hamilton 1960) | The HDRS is a ‘…widely used clinician-administered depression assessment scale.’ (https://dcf.psychiatry.ufl.edu/files/2011/05/HAMILTON-DEPRESSION.pdf accessed 22/06/23) | Multiple versions of the original 17 item scale (see website for details) (HDRS17) ‘…designed for completion after an unstructured clinical interview, there are now semi-structured interview guides available’ and scoring varies according to the version being used (https://dcf.psychiatry.ufl.edu/files/2011/05/HAMILTON-DEPRESSION.pdf accessed 22/06/23) | 12, 21 | 57 500 | |

| Streamlined Longitudinal Interval Longitudinal Follow-up Evaluation (Keller et al. 1987 as cited by Beardslee et al. 2007) | Longitudinal course of psychiatric disorders (Beardslee et al. 2007) | Measures the number of psychiatric episodes during the course of a research study (Beardslee et al. 2007) | 2, 3 | 373 | |

| Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (Cox, Holden and Sagovsky l987 as cited in Horowitz et al. 2001) | ‘The EPDS was designed to identify symptoms of postpartum depression….’ (Horowitz et al. 2001, 325) | ‘The 10-item version consists of statements describing depressive symptoms with four possible responses, each graded according to severity or duration.’ (Horowitz et al. 2001, 325) | 19 | 31 500 | |

| Global Assessment Scale (GAS; Endicottet al. 1976) | ‘…a rating scale for evaluating the overall functioning of a subject during a specified time period on a continuum from psychological or psychiatric sickness to health.’ (Endicott et al. 1976, 766) | Assesses on a scale of 0 to 100 to rate the degree to which the parents symptoms impact upon their daily life (Endicott et al. 1976) | 2, 3 | 22 700 | |

| The Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation – Outcomes Measure (Evans et al. 2002 as cited in Nordh et al. 2022) | Measure of distress in parents (Nordh et al. 2022, 1116) | 34 items with four subscales of ‘Wellbeing, Symptoms (anxiety, depression, or physical), Functioning (close relations, general, or social), and Risk to Self and/or Others…on a five-point scale’ (Nordh et al. 2022, 1116) | 31, 49 | 1700 | |

| The Patient Health Questionnaire (Kroenke et al. 2001 as cited in Aylward and Sved Williams 2023) | ‘…taken from the larger Patient Health Questionnaire…provides a criteria-based indication of depressive disorders and measure of depression severity.’ (Aylward and Sved Williams 2023, 6) | ‘…self-administered…on the 9 diagnostic criteria for DSM-IV depressive disorders, scoring each as “0” (not at all) to “3” (nearly every day).’ (Aylward and Sved Williams 2023, 6) | 1 | 70 600 | |

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (Radloff 1977 as cited in Sanford et al. 2003) | ‘…measures depressive symptoms.’ (Sanford et al. 2003, 81) | Caregivers rate 20 ‘…symptoms associated with depression, such as restless sleep, poor appetite, and feeling lonely’ with response options 0–3 ranging from rarely or none of the time to most or almost all the time (from https://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/practice-settings/assessment/tools/depression-scale accessed 21/06/23) | 36 | 73 100 | |

| Hopkins Symptom Check List 10 (Sanford et al. 2003 as cited in Kallander et al. 2021) | Measure of mental health symptoms (Kallander et al. 2021) | 10 item scale includes four anxiety and six depression items scored over the last week on a four-point scale (from 1 = ‘Not at all’ to 4 = ‘Extremely’; Kallander et al. 2021) | 20 | 2500 | |

| Hypomanic/Manic Symptoms (Chinese version; Bauer et al. 2000 as cited in Liu et al. 2023) | Assesses patients for manic/hypomanic symptoms (Liu et al. 2023) | A 15-item, self-reporting questionnaire using the visual analogue…scale format from 0 to 100 to assess status over the last 24 h (Liu et al. 2023) | 21 | 465 | |

| The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Zigmond and Snaith 1983 as cited in Nordh et al. 2022) | Measures symptoms of depression and anxiety in medical patients (Nordh et al. 2022) | The 14 item HADS scale has two subscales of depression and anxiety that are responded to on a four-point scale (Nordh et al. 2022) | 31 | 149 000 | |

| The McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (Zanarini et al. 2003 as cited in Aylward and Sved Williams 2023) | ‘…a 10 item self report measure addressing BPD based on DSM-IV BPD criteria.’ (Aylward and Sved Williams 2023, 6) | ‘Each endorsed item scores 1 point with a score of 7 or more indicating likely BPD.’ (Aylward and Sved Williams 2023, 6) | 1 | 847 | |

| Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition (Constantino and Gruber 2012 as cited in Veddum et al. 2023) | The scale is ‘…designed to identify the presence and severity of social impairments associated with autism spectrum disorders…’ (Veddum et al. 2023, 115141) | Adult and child versions (teacher completed in this study) of the 65-item rated on a 0–3 scale with social communication and interaction and restricted interests and repetitive behaviour subscales (Veddum et al. 2023) | 45 | 13 000 | |

| Parental Illness Characteristics and Severity (Self constructed by Kallander et al. 2021) | Parent perception of the duration and predictability of their illness (Kallander et al. 2021) | Two items ‘(1) “For how long have you been ill or having substance abuse problems?” This item is scored numerically by months and years. (2) “Is it difficult to know how the illness will progress in the future?” This item is scored dichotomously (“Yes” = 1, “No” = 0)’ (Kallander et al. 2021, 408) | 20 | 2 | |

| Wellbeing | EQ-5D (Sonntag et al. as cited in Radicke et al. 2021) | Self-report of health-related quality of life (Radicke et al. 2021) | Five items health-related quality of life measuring ‘…mobility, self-care, usual activity, discomfort, anxiety, and depression…’ on a three-point scale (Radicke et al. 2021, 7) | 33 | 125 000 |

| Mental health literacy | Depression Facts Quiz (Brent et al. 1993 as cited by Sanford et al. 2003) | Assesses parent knowledge ‘…about depression in parents of adolescents with depression….’ (Sanford et al. 2003, 82) (27) | Not available | 36 | 2 |

| ‘Parenting and Mental Illness’ questionnaire (self-constructed by Marston et al. 2014) | Parent perspectives on parenting with a mental illness | Self-constructed 21 items completed on a 1 (‘strongly disagree’) to 5 (‘strongly agree’) point scale regarding the parent's perspectives regarding parenting and mental illness (e.g. benefits of talking to children about parent's mental illness; Marston et al. 2014) | 23 | 175 | |

| Parent skill and/or behaviour | Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ; Shelton, Frick, and Wooton 1996 as cited in Liu et al. 2023) | Assesses the effectiveness of parenting practices and functions of parents with school age children (Liu et al. 2023) | The measure is scored on a 5-point scale from never to always and the 42-item version has five subscales of parental involvement, nurturance, poor monitoring, inconsistent discipline and application of rules (Liu et al. 2023) while the 13-item version includes the involvement and monitoring subscales (Valdez et al. 2011) | 21, 41 | 3450 |

| Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment Inventory (Caldwell and Bradley 2003; as cited in Wansink et al. 2015) | ‘…quality and quantity of stimulation and the support available to a child in the home environment through objects, events, and interactions with its parents.’ (Wansink et al. 2015, 4) | Employed the Dutch version scored yes/no questions on ‘…four dimensions of responsiveness, learning materials, stimulation and harsh parenting in semi structured observation/interviews by trained interviewers.’ (Wansink et al. 2015, 4) |

47, 48 |

878 | |

| Parenting Practices Scale (used in Canadian National Longitudinal Study of Children and Youth as cited by Sanford et al. 2003) | ‘…scale measures parenting behaviours…’ (Sanford et al. 2003, 81) | 18 items measure three subscales of positive practices, hostile-ineffective practices, and consistency factors (Sanford et al. 2003, 81) | 36 | 547 | |

| Child Report of Parenting Behavior Inventory (Schaefer 1965) | ‘…scales designed to collect children's reports of parental behavior….’ (Schaefer 1965, 413) | ‘…acceptance, rejection, and consistent discipline subscales of the revised Child Report of Parenting Behavior Inventory…’ were responded to on dimensions of ‘“like, somewhat like, or unlike” the mother.’ (Valdez et al. 2011, 6) | 41 | 149 | |

| Parent Disagreement Scale (Davis-Kean et al. 1998 as cited by Sanford et al. 2003) | Measures the ‘…parents with respect to their performance on frequent parenting practices.’ (Sanford et al. 2003, 82) | ‘This 9item scale measures agreement between parents with respect to their performance on frequent parenting practices.’ (Sanford et al. 2003, 82) | 36 | 4 | |

| Laxness and Overreactivity Subscales of the Dutch Version of the Parenting Scale (Prinzie 2004 as cited by van der Zanden et al. 2010) | Parenting styles and practices (van der Zanden et al. 2010) | ‘…12 questions from the Laxness and Overreactivity subscales of the Dutch version of the Parenting Scale…’ that respectively measure permissive and authoritarian parenting styles on a response choice of 0, ‘never or rarely’ to 7, ‘most of the time’ (van der Zanden et al. 2010, 5) | 42 | 9010 | |

| Parenting Skills Subscale of the Family Functioning Questionnaire (Ten Brink et al. 2000 as cited in Wansink et al. 2015) | Parenting Skills covering the positive aspects of parental behavior including how the parent engages children with appropriate activities and tasks (Wansink et al. 2015) | The 14 items parenting skills subscale of the Family Functioning Questionnaire covers ‘…positive aspects of parental behavior such as encouragement, attention, structuring, and authoritative control…’ that is scored on a 1 (does not apply to this family) to 5 (strongly applies to this family) scale (Wansink et al. 2015, 4) | 47 | 598 | |

| Parental Monitoring (Kerr and Stattin 2000) | Measures…‘parental monitoring…as tracking and surveillance…parental knowledge…linked to better adolescent adjustment.’ (Kerr and Stattin 2000, 366) | Parent completed nine parental monitoring items ‘…on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1) “never” to (5) “often” assessing what parents know about their adolescent's whereabouts, activities, and associations.’ (van Loon et al. 2014, 1206) | 43 | 65 300 | |

| Parenting Scale (Arnold et al. 1993) | ‘…scale to measure dysfunctional discipline practices in parents of young children.’ (Arnold et al. 1993, 137) | Parent complete 21 items on a seven-point scale that measures laxness and over-reactivity subscales (Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, van der Zanden, et al. 2022; Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, Weeland, et al. 2022) | 34 | 9010 | |

| The Parenting Style Inventory (Krohne and Pulsack 1991 as cited in Lochner et al. 2021) | ‘…covering positive (support, praise) and negative (criticism, restraint, inconsistency) parenting styles….’ (Lochner et al. 2021, 7) | ‘… 65-item child-report questionnaire…on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = “never or rarely happens” to 4 = “always happens”).’ (Lochner et al. 2021, 7) | 22 | 358 | |

| Parenting Capacity (self constructed by Kallander et al. 2021) | Measures the impact on parenting capacity during illnesses including substance abuse, mental illness and/or severe physical illness (Kallander et al. 2021) | Eight items that measure the degree the parents' illness impacts negatively on such things as ‘emotionally supporting the child’ and ‘maintaining structure in everyday life’ and scored on a four-point scale from 0 to 3 with higher scores indicating lower parenting capacity (Kallander et al. 2021) | 20 | 2 | |

| Middle Childhood HOME Inventory (Bradley et al. 1988 as cited in Thorup et al. 2022) | ‘…designed to identify potentially inadequate home environments that could pose a risk to a child's development.’ (Thorup et al. 2022, 3) | ‘…eight subscales…that measure different aspects of stimulation and support available in the home environment…Duration is approximately 45–60 min. No specifc cut-of scores are defined of a risk environment….’ (Thorup et al. 2022, 3) | 40 | 43 | |

| Parental Involvement with their Child's Treatment (self constructed by Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, van der Zanden, et al. 2022; Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, Weeland, et al. 2022) | Parental involvement in child's treatment (Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, van der Zanden, et al. 2022; Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, Weeland, et al. 2022) | Scale of 0 to 10 the parent's involvement with their child's treatment (Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, van der Zanden, et al. 2022; Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, Weeland, et al. 2022) | 35 | 273 | |

| Parenting competence | Parenting Competence and Incompetence Scale (combination measure self constructed by Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, van der Zanden, et al. 2022; Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, Weeland, et al. 2022) | ‘Taken from two questionnaires to… assesses the perceived efficiency as a parent…feelings of inadequacy as a parent.’ (Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, van der Zanden, et al. 2022; Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, Weeland, et al. 2022, 10) | ‘Five self-agency items taken from the Parenting Self Agency Measures (Dumka et al. 1996) and six items from the Dutch version of the Parenting Stress Index.’ (Abidin 1983; as cited in Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, van der Zanden, et al. 2022; Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, Weeland, et al. 2022) | 34, 42 | 2 |

| The Karitane Parenting Confidence Scale (Crncec et al. 2008a, as cited in Aylward and Sved Williams 2023) | ‘…used to assess the unidimensional construct Perceived Parental Self-Efficacy (PPSE) in parents with infants aged 0–12 months.’ (Aylward and Sved Williams 2023, 6) | ‘This 15-item scale…Grounded in Bandura self-efficacy theory…items…‘task specific’ nature…with clinical cut-off scores: ‘severe clinical’ range <31 to ‘…non-clinical’ range ≥40’ (Aylward and Sved Williams 2023, 6) | 1 | 160 | |

| Sense of Parenting Competence Scale (Used in the Canadian National Longitudinal Study of Children and Youth as cited in Sanford et al. 2003) | Sense of Parenting Competence Scale ‘…measures respondents' sense of competence as a parent.’ (Sanford et al. 2003, 82) | The PSOC is a 17 item scale, with two subscales and each item is rated on a six point strongly disagree to strongly agree (accessed from https://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/sps/documents/c-change/parenting-sense-of-competence-scale.pdf 21/06/23) | 36 | 2 | |

| Perceived Parental Control (Campis et al. 1986 as cited in Wirehag Nordh et al. 2023) | Measures the parent's experience of control in rearing situations in relation to the child (Wirehag Nordh et al. 2023) | The 10 items subscale of the parental locus of control scale assesses parenting control on a five point scale with higher scores more control (Wirehag Nordh et al. 2023) | 49 | 2430 | |

| Parenting stress | Parenting Daily Hassles (PDH) (Crnic and Greenberg 1990, as cited in Wansink et al. 2015) | ‘The PDH has 20 typical everyday events concerning parenting tasks and challenging child behavior, for instance “the kids resist or struggle with you over bed time”.’ (Wansink et al. 2015, 4) | The 20 events are scored according to frequency (1 rarely to 5 constantly) and intensity 1 no hassle to 5 big hassle) to create daily hassle subscales of typical everyday events concerning parenting tasks and challenging child behaviours (Wansink et al. 2015) |

47 |

1320 |

| The Parenting Stress Index Short Form (Abidin 1995 as cited in Aylward and Sved Williams 2023) | ‘Total Parenting Stress’ measuring personal factors contributing to parent distress, perception of child not meeting expectations and difficulty managing challenging behaviours (Aylward and Sved Williams 2023, 5) | Three 12 item subscales measuring: ‘Parental Distress…Parent–Child Dysfunctional Interaction…Difficult Child… Scores are interpreted relative to percentiles from a normative sample….’ (Aylward and Sved Williams 2023, 6) | 1 | 12 600 | |

| Dutch Questionnaire on Long-term Difficulties (De Jong et al. 1996 as cited by van Santvoort et al. 2014) | Long term difficulties of parental stress (van Santvoort et al. 2014) | Employed the Dutch validated LLM to assess the degree that parents ‘…experienced stress in 14 different areas such as…’ financial, relationship problems (van Santvoort et al. 2014, 448) | 44 | 2 | |

| Trauma and stressful experiences | Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Scale-Interview Version (Foa et al. 1993 as cited in Nicholson et al. 2009) | ‘Trauma symptom severity…indicating the extent to which the respondent was bothered by each PTSD symptom.’ (Nicholson et al. 2009, 109) | ‘…measured by the total score of the 17item…rated from “1 = not at all” to “4 = almost always”…in the past 30 days.’ (Nicholson et al. 2009, 109) | 29, 30 | 626 |

| Coping | Freiburg Questionnaire of Coping with Illness (Muthny 1989 as cited in Radicke et al. 2021) | Styles of coping with mental illness (Radicke et al. 2021) | The 23 item questionnaire ‘…generates five subscales that represent the respondent's predominant coping….depressed processing style, active problem-oriented coping, distraction and self-growth, religiosity and quest for meaning, trivialization, and wishful thinking…on a four-point response scale….’ (Radicke et al. 2021, 7) | 33 | 184 |

| Help seeking and service need | Parent Service Needs (self constructed by Nicholson et al. 2009) | ‘Services needed but not received during the prior three months…’ (Nicholson et al. 2009, 109) | ‘…endorsed by mothers in six areas including mental health, substance abuse, housing, child care, parenting, and employment. The highest possible score for each family was six….’ (Nicholson et al. 2009, 109) | 29, 30 | 35 |

| Within family relationships and supports | Relationship Support Inventory (Scholte, van Lieshout and van Aken 2001) | ‘Relational support from 4 key providers (father, mother, special sibling, and best friend) on 5 provisions (quality of information, respect for autonomy, emotional support, convergence of goals, and acceptance)’… for adolescents (Scholte et al. 2001, 71) | Parents filled out the 12 items to assess parental support. The scale has response choices (1) ‘absolutely untrue’ to (5) ‘absolutely true’ (e.g. ‘I show my child that I love him/her’; van Loon et al. 2014, 1206) | 43 | 24 |

| Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Sabourin et al. 2005 as cited in Valdez et al. 2011) | Designed to assess the relationship quality of intact (married or cohabiting) couples (Valdez et al. 2011) | The 4-item Dyadic Adjustment Scale is based on the 32 item version (Sabourin et al. 2005) completed using 2, 5, 6 and 7 point response formats (Valdez et al. 2011, 5) | 41 | 20 200 | |

| The Nursing Child Assessment Satellite Training Parent–Child Interaction Teaching Scale (Sumner and Spitz 1994 as cited in Aylward and Sved Williams 2023) |

‘…73 item observational tool used to measure the quality of the parent–child interaction with children up to 36 months…theoretically grounded in the Barnard model’ (Aylward and Sved Williams 2023, 6) |

‘…composite scales of …the overall quality of the interaction…sensitivity to cues…clarity of cues’ (Aylward and Sved Williams 2023, 6) | 1 | 6 | |

| Outside family relationships and supports | Modified Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey (Sherbourne and Stewart 1991 as cited in Nicholson et al. 2009) | ‘Perceived social support in the previous six months…’ (Nicholson et al. 2009, 109) | ‘…items reflecting emotional, social, and tangible supports were rated from “1 = none of the time” to “5 = all of the time”.’ (Nicholson et al. 2009, 109) | 29, 30 | 451 |

| Parental Access to Care and Social Support (self constructed by Kallander et al. 2021) | Aims to measure the parent's level of access to care and social support (Kallander et al. 2021) | The three item scale measures access to homebased services (‘Yes’ = 1, ‘No’ = 0) and two further items scored by number of hours of help/support received (Kallander et al. 2021) | 20 | 2 | |

| Dutch Social Support List-Interactions (Van Eijk et al. 1994 as cited in Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, van der Zanden, et al. 2022; Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, Weeland, et al. 2022) | Measures parents perceived social support (Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, van der Zanden, et al. 2022; Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, Weeland, et al. 2022) | The 12 item scale has subscales ‘…of social support, everyday support, support in problem situations and esteem support, on a four-point Likert scale’ and together they are scored as ‘…the total social support as perceived by parents.’ (Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, van der Zanden, et al. 2022; Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, Weeland, et al. 2022, 10) | 34 | 3 | |

| Interpersonal Support Evaluation List-12 (Cohen and Hoberman 1983 as cited in Kallander et al. 2021) | Measures positive events and interpersonal and social support (Kallander et al. 2021) | The 12-item version is a short form of 40-item version with each item scored on a 0–3 four-point scale (Kallander et al. 2021) | 20 | 535 | |

| Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (Procidano and Heller 1983 as cited in Valdez et al. 2011) | The scale measures perceived support from families, friends and others (Valdez et al. 2011) | The 12-item measure of support from families, friends and and significant others on a 1–7 point scale (Valdez et al. 2011) | 41 | 23 700 | |

| Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire (Broadhead et al. 1988 as cited in Liu et al. 2023) | Assesses the level of perceived social support (Liu et al. 2023) | The 8 item Chinese version assesses two components of affective and confidant support ‘…using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = much less support than I would like; 5 = as much support as I would like).’ (Liu et al. 2023, 4) | 21 | 1800 |

Within each of the parent–young person-family groupings, initial codes were applied by the first author to the measures used in each study to capture the types of outcomes being measured (e.g. specific psychopathology, mental health literacy, quality of life and parenting efficacy). These initial codes were then iteratively reread against the studies in which they were used and across and within each grouping in the three tables. Through this process, the codes were amalgamated into categories to represent the types of outcome measures used in the studies (column 1). Each of the categories was independently examined and validated following discussion by the fifth author and then by the larger team. The final outcome categories, measures, purpose and items/subscales of research undertaken with parents, young people and families are illustrated in the tables below and are combined in a summary Table (5) according to parents, young people and families.

After sorting outcome themes, it became clear that there were a group of diagnostic instruments that we did not consider to be ‘outcomes’ such as the Diagnostic Interview Schedule and Structured Clinical Interview for DSM, among others. They were removed from the table based upon the rationale that diagnostic interviews seek to establish the presence and level of mental illness for the person with the mental health problem—not to measure outcomes themselves.

The issue of diagnostic versus screening instruments was further highlighted with some FaPMI literature utilising instruments in multiple capacities. For example, the Beck Depression Inventory has been used as a both a screening/diagnostic instrument and as an outcome measure in different studies. Compas et al. (2009) employed it as a 3-time point outcome measure whereas Cicchetti et al. (2000) used it simply as a baseline screening instrument. Notably both authors utilised other diagnostic measures in their research. The measures that were used clearly for only diagnostic purposes were removed whereas measures used for outcomes (e.g. BDI) remained in the review.

4 Results

The authors, country, study design, sample characteristics and quality rating of the 50 studies are shown in Table 1. The number in the left column is also used in Tables 2–4 to illustrate the authors who used the survey instrument/s in their research.

Country representation ranged from the United States with 14 studies, Australia (10), Netherlands (9), Denmark (5), Germany (3), Sweden (2) and single studies from Canada, China, Finland, France, Norway, Taiwan and the United Kingdom. Across the studies, there were a total of 2571 parents with mental illness in the studies (not including duplicates nor those with no parental illness), of which 2290 (88%) were mothers. There were also 8244 children across the studies and 4051 (49%) were girls. Ages of children ranged from 3-year-old toddlers (Verduyn et al. 2003) to adult children 36 years of age (Zwicker et al. 2023). Two of the studies included children under 5 years of age, 22 from 6 to 11 years, 11 from 12 to 17 years and 6 with adult children (18 years and over).

4.1 Parent Outcome Categories

Table 2 highlights 51 measures grouped according to 11 parent outcome categories. These were the parent's; mental illness/psychopathology (16), wellbeing (1), mental health literacy (2), parenting skills/behaviours (13), parenting competence (4), parenting stress (3), trauma and stressful experiences (1), coping (1), help-seeking/service need (1), within family (3) and outside family relationships and supports (6). The instruments used to quantify the parent's mental illness/psychopathology outcomes were both general and specific. The most regularly used general measure (seven studies) was the Brief Symptom Inventory, measuring multiple symptom dimensions and levels of distress associated with the illness (Derogatis and Melisaratos 1983). The most regularly measured specific condition was depression, where ten studies used five different scales, most commonly, versions of the Beck Depression Inventory (six studies). Other instruments were used to measure specific illness characteristics (e.g. anxiety, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Nordh et al. 2022; autism using the Social Responsiveness Scale, Veddum et al. 2023).

Where 24 different studies measured aspects of mental illness/psychopathology, only one (Radicke et al. 2021) measured the well-being of the parent using the EQ-5D to assess quality of life. In addition, only two groups of authors assessed parental mental health literacy (Sanford et al. 2003; Marston et al. 2014) and one group of authors (two studies; Nicholson et al. 2009, 2016) measured trauma and stressful experiences of parents as a research outcome.

Alternatively, parenting was a common research outcome which is not surprising given the topic area of parental mental illness. Specific parenting behaviours/skills outcomes were most regularly assessed and included types of parenting practices by Sanford et al. (2003) using the Parenting Practices Scale, parental monitoring of children (van Loon et al. 2014) and Kallander et al. (2021) who measured parenting capacity during the mental illness. Concepts of parent agency and parent stress were measured less often, with the former measuring perceptions of competence (Sanford et al. 2003) and latter such things as daily parenting hassles (Wansink et al. 2015, 2016).

Six outcomes were associated with relationships and supports outside of the family while three were linked with relationships and supports within the family for parents. Notably only one of these relationship/support measures was used by more than once, by Nicholson et al. in two papers (2009, 2016).

In total, only 14 of the 52 outcome measures were used by more than one group of researchers, most often (seven) to measure parental mental illness/psychopathology. Only three of those were used on more than two occasions—the Brief Symptom Inventory (seven times), Beck Depression Inventory (six) and the SF36 on four occasions. Of the remaining 11 measures that were used more than once, these were each used on only two occasions and as above were often by the same author groups (e.g. Wansink et al. 2015, 2016; Beardslee et al. 2003, 2007). Across the parenting and relationship categories only 5 of the 26 instruments were used by more than one author group.

4.2 Young People Outcome Categories

Table 3 shows 73 outcomes for young people grouped into 11 categories of: Mental illness/psychopathology (20 times), Well-being (9), Mental health literacy (4), Cognitive functioning (7), Trauma and stressful experiences (4), Caregiving (4), Coping (7), Help Seeking/Service Need (4), Within Family (2) and Outside Family Relationships and Supports (9) and ‘other’ (3). The ‘other’ category included outcomes that could not be grouped elsewhere and included such things as the young person's level of level of guilt/shame (Bosch et al. 2020) and polygenic scores in a gene study by Zwicker et al. (2023).

| Outcome concept | Instrument/informant | Purpose/definition | Items/subscales | Used by | GS cites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health/psychopathology | Child Behavior Checklist (https://aseba.org/aseba-overview/ accessed 4/7/23)a | ‘…used to assess symptoms of anxiety/depression (as a measure of general emotional distress) and total internalizing and externalizing problems in children and adolescents.’ (Compas et al. 2009, 5) | Parent or carergivers rate the 118 items from 0 to 2 on ‘…8 subscales of withdrawn, somatic complaints, anxious/depressed, social problems, thought problems, attention problems, delinquent behavior, aggressive behavior) and a total score.’ (Radicke et al. 2021, 7) | 8, 9, 10, 12, 22, 33, 37, 38, 39, 46 | 138 000 |

| Youth Self-Report, Young Adult Self-Report (see https://aseba.org/aseba-overview/ accessed 270704) | The scales are part of the ASEBA questionnaires (see below) and are used to assess the degree of internalizing and externalising symptoms (Beardslee et al. 2007) | As above and see https://aseba.org/aseba-overview/ accessed 230704 for details | 2, 3, 9, 10, 22, 43 | 36 600 | |

| Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman 1997) | The SDQ measures emotional and behavioural difficulties and behavioural strengths in young people up to 17 years of age ‘…that can be completed by adolescents, parents, workers…’ (https://www.sdqinfo.org/a0.html accessed 230614) | 25 items and 5 subscales (emotional, conduct, hyperactivity/inattention, peer relationship problems and prosocial behaviour in 2–17 year olds scored on 3 point response format (available for download at https://www.sdqinfo.org/a0.html accessed 230614) | 13, 24, 26, 32, 34, 35, 38, 42, 44, 47, 49 | 40 600 | |

| Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia original authors (Endicott and Spitzer 1978; Kiddie-SADS-E-R; Puig-Antich et al. 1980 as cited in Beardslee et al. 2003) | The SADS describes ‘…current episode of illness…severity…progression…and …past psychopathology and functioning…’ (Endicott and Spitzer 1978, 696) | There are multiple versions and developments to the interview schedule. ‘The K-SADS-PL interview was performed firstly with the primary caregiver and then with the child…’ with a focus upon ADHD and such things as conduct disorder along with other elements to supplement the interview (Spang, Hagstrøm, et al. 2022; Spang, Thorup, et al. 2022, 4) | 2, 5, 8, 38 | 49 300 | |

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (Radloff 1977 in Sanford et al. 2003) | See Table 2 for details | See Table 2 for details | 8, 9, 10, 15 | 73 100 | |

| Children's Global Assessment Scale (Shaffer et al. 1983) | The CGAS is standardized measure of young people's functioning and impairment ‘…for a child or adolescent during a specified time period’ (Shaffer et al. 1983, 1228) | Young people 4–16 years of age are assessed through clinician judgment of functioning on a scale from 1 (impaired) to 100 (health functioning) with… ‘Scores above 70 on the CGAS are designated as indicating normal function.’ (Shaffer et al. 1983, 1228) | 28, 37, 38 | 6 090 000 | |

| Children's Depression Inventory (Weissman et al. 1977) | ‘…sensitive tool for detecting depressive symptoms and change in symptoms over time in psychiatric populations…’ (Weissman et al. 1977, 203) | ‘…completed by the patient and oriented around symptoms of depression. It asks for feelings during the week preceding the interview…answers…from 0 to 3….’ (Weissman et al. 1977, 206) | 14,32,36 | 861 000 | |

| Symptoms of depression (child) German version (Stiensmeier-Pelster et al. 2014 as cited in Lochner et al. 2021) | ‘…directly based on the DSM-criteria for depression…’ (Lochner et al. 2021, 7) | ‘…26-items scored on a 3-point Likert scale. …’ (Lochner et al. 2021, 7) | 22 | 81 | |

| Global Assessment of Functioning scale (As cited in https://www.concordia.ca/content/dam/concordia/services/health/docs/forms/global-assessment-of-functioning-scale.pdf accessed 230711) | Assesses ‘…psychological, social, and occupational functioning on a hypothetical continuum of mental health-illness…’; as cited in https://www.concordia.ca/content/dam/concordia/services/health/docs/forms/global-assessment-of-functioning-scale.pdf accessed 230711) | ‘Interviewers rated severity of impairment using the…GAF…’ with scores ranging from 1 (severely impaired) to 100 (extremely high functioning; Clarke et al. 2001, 1129) | 8 | 10 400 | |

| Eyberg Child Behaviour Inventory (Robinson et al. 1980 as cited in Verduyn et al. 2003) | ‘Mother completed…conduct problem behaviours, standardised on children 2–7 years old’ (Verduyn et al. 2003, 343) | ‘…a 36-item inventory of child conduct problem behaviours…children 2–7 years old….’ (Verduyn et al. 2003, 343) | 46 | 869 | |

| Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (Keller et al. 1987 as cited in Garber et al. 2009) | Parent and young people interviewed about recent psychiatric symptoms, functioning and treatment history (Garber et al. 2009) | ‘…interviewed about… symptoms and onset and offset of disorders since the last assessment… score from 1 through 6…for each week of the follow-up period.’ (Garber et al. 2009, 4) | 15 | 2706 | |

| Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HDRS, Hamilton 1960) | See Table 2 for details | See Table 2 for details | 8 | 57 500 | |

| Beck Depression Inventory (see Table 2 for details) | See Table 2 for details | See Table 2 for details | 32 | 394 000 | |

| Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS; Lancon et al. as cited in Garosi et al. 2023) | Clinician assessment to depressive symptomatology in Schizophrenia (https://cumming.ucalgary.ca/research/calgary-depression-scale-schizophrenia/home accessed 230704) | Nine items assess depression symptoms over a 2-week period on a four point scale from absent (0) to severe (3) (https://cumming.ucalgary.ca/research/calgary-depression-scale-schizophrenia/home accessed 230704) | 16 | 3890 | |

| The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (https://www2.psy.unsw.edu.au/dass/over.htm accessed 230705) | ‘…measure the negative emotional states of depression, anxiety and stress…’ (for a detailed description see https://www2.psy.unsw.edu.au/dass/over.htm accessed 230705) | ‘…self-report scales…’ of depression, anxiety and stress ‘…4-point severity/frequency scales to rate the extent to which they have experienced each state over the past week’ (https://www2.psy.unsw.edu.au/dass/over.htm accessed 230705) | 25 | 13 600 | |

| Health of the Nation Outcome Scales for Children and Adolescents (Gowers et al. 1999 as cited in Naughton et al. 2019) | ‘The tool is used to guide day-to-day clinical practice and to measure social and health outcomes’ (Naughton et al. 2019, 1059) | ‘HoNOSCA consists of two sections. Part A has a clinical focus, while Part B explores service recipients' understanding of their problems and knowledge of services.’ (Naughton et al. 2019, 1059) | 28 | 757 | |

| Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (Kay et al. 1987 as cited in Garosi et al. 2023) | Clinician assessment of psychotic symptomatology for schizophrenia (Garosi et al. 2023) | 30-item psychotic symptomatology scale creates positive and negative factors…rated on 7 points from levels of psychopathology absent (1) to extreme (7; Kay et al. 1987) | 16 | 61 700 | |

| The attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder-rating scale (Barkley et al. 1999 as cited in Spang, Hagstrøm, et al. 2022; Spang, Thorup, et al. 2022) | Assesses the level of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Spang, Hagstrøm, et al. 2022; Spang, Thorup, et al. 2022) | Eighteen items in this study were rated independently by ‘Primary caregivers and the child's teacher…’ (Spang, Hagstrøm, et al. 2022; Spang, Thorup, et al. 2022, 1108) | 37 | 521 | |

| Positive and Negative Affect Scale for Children (Laurent et al. 1999 as cited in Foster et al. 2016) | ‘…designed to discriminate between anxiety and depression symptoms in young people’ (Foster et al. 2016, 298) | ‘…can be separated into two subscales: positive… (12 items) and negative affect (15 items)…rated on a five point scale (1 = not much at all to 5 = a lot).’ (Foster et al. 2016, 298) | 13 | 742 | |

| Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition (Constantino and Gruber 2012 as cited in Veddum et al. 2023) | See Table 2 for details | See Table 2 for details | 45 | 13 000 | |

| Wellbeing | KIDSCREEN-27 and KIDSCREEN-10 (The KIDSCREEN Group Europe 2006 as cited in Kallander et al. 2021) | ‘…assess the subjective health and the psychological, mental and social well-being of children and adolescents (HRQoL) between the ages of 8 and 18’ (see https://www.kidscreen.org/english/questionnaires/ accessed 11/07/23) | ‘…measures physical well-being (five items), psychosocial well-being (seven items), peer relations and social support (four items), autonomy and parent relations (seven items) and school environment (four items)…scored on a five-point…‘Not at all’ = 1 to ‘Very much’ = 5’ (note Norwegian version, Kallander et al. 2021, 407) | 20, 33 | 10 700 |

| Satisfaction with Life (Diener et al. 1985 as cited in Fraser and Pakenham 2008) | Assesses the general satisfaction with life (Fraser and Pakenham 2008) | Five items ‘…measure global life satisfaction…rate…on a 7 point scale (1strongly disagree, 7strongly agree)….’ (Fraser and Pakenham 2008, 1043). | 14 | 312 000 | |

| Rosenberg-Simmons Self-esteem scale (Rosenberg 1979 as cited in Goodyear et al. 2009) | ‘…is used as an indicator of global self esteem’ (Goodyear et al. 2009, 300) | ‘…6-item scale…modified from the 10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale for Adolescents…scored on a three point scale (0–2), with higher numbers signifying high self-esteem.’ (Goodyear et al. 2009, 300) | 17 | 33 | |

| The Mental Health Inventory (Veit and Ware 1983, as cited by Mechling 2015) | ‘…assess psychosocial well-being….’ (Mechling 2015, 574) | ‘…a 37-item self-report measure…two global scales (psychological well-being and psychological distress). “…response on a 1–6 scale (1 = always…6 = never)”.’ (Mechling 2015, 574) | 27 | 4780 | |

| The Mental Health Continuum short form (Keyes 2002 as cited in Maybery et al. 2022) | ‘…was used to measure emotional, social and psychological wellbeing’ (Maybery et al. 2022, 1254) | ‘The short form consists of 3 emotional…6 psychological…and 5 social well-being items…6-point Likert scale ranging from 0 “never” to 5 “everyday”’ (accessed from https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/health-happiness/mental-health-continuum-short-form/ on 230929) | 25 | 9420 | |

| The General Self-Efficacy Scale (Schwarzer and Jerusalem 1995 as cited in Maybery et al. 2022) | ‘…was created to assess a general sense of perceived self-efficacy…to predict coping with daily hassles…after experiencing all kinds of stressful life events’ (accessed from https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft00393-000 on 230829) | ‘…10-item version…is designed for the general adult population, including adolescents…items are designed to tap…successful coping and implies an internal-stable attribution of success’ (accessed from https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft00393-000 230829) | 25 | 14 700 | |

| The Perceived Competence Scale for Children (Harter 1988; Treffers et al. 2002 as cited in Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, van der Zanden, et al. 2022; Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, Weeland, et al. 2022) | ‘…used to measure children's perceived competence…’ (Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, van der Zanden, et al. 2022; Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, Weeland, et al. 2022, 78) | ‘Subscales social acceptance and global self-worth…’ each ‘…contain five items measured on four-point Likert scales…has been widely used by researchers in the field of intellectual disabilities’ (Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, van der Zanden, et al. 2022; Riemersma, van Santvoort, van Doesum, Hosman, Janssens, Weeland, et al. 2022, 78) | 35 | 7920 | |

| Children's Hope Scale (Snyder et al. 1997 as cited in Foster et al. 2016) | ‘…assess a child's dispositional hope…agency (ability to initiate and sustain goal directed action), and pathways (ability to find a means to achieve goals)’ (Foster et al. 2016, 298) | ‘…six-item self-report questionnaire…rated on a six-point scale (1 = none of the time to 6 = all of the time).’ (Foster et al. 2016, 298) | 13 | 913 | |

| Herth Hope Scale (Herth 1991 as cited in Mechling 2015) | ‘…evaluate degree of hope…’ experienced by the young person (Mechling 2015, 574) | ‘This is a brief, 12-item self-rated tool that is answered on a 4-point scale (1 = strongly disagree…4 = strongly agree).’ (Mechling 2015, 574) | 27 | 1030 | |

| Mental health literacy | Mental Health Literacy Scale (Khan et al. 2010 as cited in Mechling 2015) | Assesses the young person's awareness and understanding of a parent's depression (Mechling 2015) | ‘Subscales were knowledge of depressive symptoms…awareness of parental depression, perceptions of what can cause depression…and knowledge regarding treatment….’ (Mechling 2015, 573) | 27 | 967 |

| Children's Knowledge of Mental Illness Scale (Goodyear, Maybery and Reupert 2005) | Scale assesses young person's attitude and knowledge about mental illness focusing upon lower scores reflecting misguided beliefs/attitudes and higher scores greater knowledge and accepting attitudes (Davies et al. 2022) | 7 item scale with response true, false or don't know. Higher scores reflect greater knowledge (Davies et al. 2022) | 11 | 1 | |

| Children's knowledge of depression (Allgaier et al. 2011 as cited in Lochner et al. 2021) | ‘…assesses children's knowledge of the symptoms and treatment of depression…’ (Lochner et al. 2021, 7) | ‘…using 50 items (e.g. “suffering from depression means that someone is crazy”…answered in a 4-point Likert scale (0 = “not at all true”, =“completely true”)’ (Lochner et al. 2021, 7) | 22 | 3 939 000 | |

| Birchwood insight scale (Birchwood et al. 1994 as cited in Garosi et al. 2023) | Level of insight that patient has into symptoms (Garosi et al. 2023) | Measures three dimensions of insight ‘…insight into illness, insight into symptoms and awareness of the need for psychotropic treatment’ (Garosi et al. 2023, 3) | 16 | 499 | |

| Cognitive functioning | Cognitions regarding parental mental illness (self constructed by van Santvoort et al. 2014) | Assessed children's cognitions in relation to the parental illness (van Santvoort et al. 2014) | ‘…three…questions about guilt, shame, and loneliness…on a five-point Likert scale (never–always)’. Combined into a single score with ‘…a high score indicating negative cognitions’ (van Santvoort et al. 2014, 6) | 34, 35, 44 | 3 |

| WPPSI-R (Wechsler 1989 as cited in Cicchetti et al. 2000) and WAIS (Stinissen 1970 as cited in Havinga et al. 2018) | ‘…assessing intelligence in children age 3–7’ (Cicchetti et al. 2000, 141) | ‘…individually administered clinical measure …organized into Verbal and Performance…yielding a Verbal IQ, Performance IQ…’ from 4 subtests each (Cicchetti et al. 2000, 141) | 7 | 234 000 | |

| British Ability Scales short form (Elliott 1987 as cited in Verduyn et al. 2003) | ‘…a brief developmental assessment of the…’ child's cognitive ability and overall IQ (Verduyn et al. 2003, 343) | ‘…a brief developmental assessment of…vocabulary, verbal comprehension, digit recall and basic number skills, yielding scores for individual scales as well as overall IQ.’ (Verduyn et al. 2003, 343) | 46 | 4610 | |

| Bayley Scales of Infant Development (Bayley 1969 as cited in Cicchetti et al. 2000) | ‘… assesses developmental level in cognitive and motor areas’ (Cicchetti et al. 2000, 141) | ‘…use with infants and toddlers up to 30 months of age…’ (Cicchetti et al. 2000, 141) | 7 | 30 600 | |

| Children's Attributional Style Questionnaire-Revised (Thompson et al. 1998 as cited in Punamäki et al. 2013) | The questionnaire measures children's causal explanations for positive and negative events (Punamäki et al. 2013) | ‘…includes positive and negative attribution-style scores…of 24 hypothetical events…12 positive…and 12 negative events…scored 0 or 1…’ (Punamäki et al. 2013, 685) | 32 | 79 900 | |

| Child attributional style (Stiensmeier-Pelster et al. 1994 as cited in Lochner et al. 2021) | Assesses how children attribute the cause of events (Lochner et al. 2021) | ‘…consists of eight positive and eight negative situations whose causes are rated on a 4-point scale in three dimensions: external vs. internal…instable vs. stable…specific vs. global…’ (Lochner et al. 2021, 7) | 22 | 146 | |

| Children's Locus of control (Nowicki and Strickland 1973 as cited in Kallander et al. 2021) | Assesses children’ degree and direction of control (Kallander et al. 2021) | ‘…14 items (8 for internal and 6 for external LoC)…scored…”Yes” = 1, “No” = 0…’ (Kallander et al. 2021, 408) | 20 | 1260 | |

| Trauma and stressful experiences | The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (Wright et al. 2001) | ‘The CTQ is a retrospective self-report instrument designed to examine the traumatic childhood experiences of adults and adolescents…’ (Wright et al. 2001, 179) | The 28 trauma items assess ‘…childhood trauma: emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect…’ and are rated on a ‘1 (never) to 5 (very often) scale’ (Wright et al. 2001, 179) | 16 | 14 700 |

| Cumulative Risk Index (Nordh et al. 2022) | Historical factors associated with or contribute adverse child mental health and wellbeing (Nordh et al. 2022) | Six risk factors coded as YES/NO (if absent): ‘…young child age (8–10 years), low social status of parent, single parenthood, parent score above the clinical cut-off on the CORE-OM Symptoms subscale, long contact with specialised psychiatric services…low perceived parental control….’ (Nordh et al. 2022, 1117) | 31 | 1640 | |

| Coddington Life Events Record (Coddington 1972 as cited in Valdez et al. 2011) | ‘Mothers and children…reported stressful life events…’ (Valdez et al. 2011, 6) | ‘LER is significant…for mother–child dyads in which the child was distressed’ (Valdez et al. 2011, 6) | 41 | 87 | |

| Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al. 1983 as cited in Mechling 2015) | ‘…assesses the degree to which situations in an individual's life feel uncontrollable, overloaded, and unpredictable…’ (Mechling 2015, 574) | ‘…a 14-item self-report measure…Stress experienced by participants during the parent's depression…on a 5-point scale…’ (Mechling 2015, 574) | 27 | 71 200 | |

| Caregiving | Multidimensional Assessment of Caring Activities Checklist (Joseph et al. 2009) | ‘…self-report measure…used to provide an index of the total amount of caring activity undertaken by the young person…’ (Joseph et al. 2009, 518) | Scores on the 18 ‘…self-report items…caregiving activities including: domestic tasks, personal care, emotional care, sibling care, household management, and financial/ practical care, with a total possible maximum score of 36’ (Joseph et al. 2009, 518) | 20, 27 | 119 |

| Positive and Negative Outcomes of Caring Questionnaire (Joseph et al. 2009) | ‘…self-report measure that can be used to provide an index of positive and negative outcomes of caring’ (Joseph et al. 2009, 518) | The 20 items are rated on a 0 = never to 3 = a lot of the time that reduce to positive and negative subscale scores (Joseph et al. 2009) | 20, 27 | 118 | |

| Hours spent on caregiving (self constructed by Kallander et al. 2021) | Amount of responsibility taken in caregiving (Kallander et al. 2021) | On a five point scale ‘How many hours do you help out or take responsibility at home during an ordinary week?’ from 1 to 4 through to‘50 h or more (Kallander et al. 2021, 408) | 20 | 223 | |

| The Young Caregiver of Parents Inventory (Pakenham et al. 2006 as cited in Fraser and Pakenham 2008) | ‘…assess participants' caregiving experiences related to caring for their parent with mental illness’ (Fraser and Pakenham 2008, 1044) | The 8 item ‘YCOPI has two parts…respondent's contributions to the family and parental tasks and functions…caregiving to the disabled/ill parent…rated on a 5 point scale of agreement (1strongly disagree, 4strongly agree)’ (Fraser and Pakenham 2008, 1044) | 14 | 20 | |

| Coping | Child Coping Strategies Checklist (Ayers et al. 1991 https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft42024-000 accessed 230712) | ‘…estimate their use of…specific types of coping….’ (Valdez et al. 2011, 6) | ‘…is a 45-item self-report inventory in which children describe their coping…’ according to ‘…11 conceptually distinct categories…’ (see https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft42024-000 accessed 230712) | 41 | 35 |

| Coping Efficacy Scale (Sandler et al. 2000 as cited in Valdez et al. 2011) | ‘…assess satisfaction with how they handled recent problems and anticipated satisfaction when dealing with future problems’ (Valdez et al. 2011, 6) | ‘…the Coping Effi cacy Scale…A two factor model…relates to…children's internalizing problems…the adaptive skills and behavior and emotional problems of the child…’ (Valdez et al. 2011, 6) | 41 | 323 | |

| Kids Coping Scale (Maybery et al. 2009 as cited in Goodyear et al. 2009) | ‘…designed to reflect distinct cognitive and behavioural coping actions….’ (Goodyear et al. 2009, 300) | ‘…three clear factors representing problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping and social support…9-items…’ for late childhood to early adolescence ‘…on a three point Likert scale, from “never” (0) to “a lot” (2).’ (Goodyear et al. 2009, 300) | 17 | 40 | |

| Responses to Stress Questionnaire (Connor-Smith et al. 2000; Jaser et al. 2005, 2008 as cited in Compas et al. 2010) | ‘…to assess how adolescents responded to stressors related to their parents' depression….’ (Compas et al. 2010, 5) | Rated separately by adolescents and their parents ‘…items cover five factors of coping and stress responses: primary control engagement coping, secondary control engagement coping, disengagement coping, involuntary engagement/stress reactivity, and involuntary disengagement’. On a scale of ‘1 = “not at all” to 4 = “a lot”’ (Compas et al. 2010, 5) | 9 | 909 | |

| The Brief Cope Inventory (Carver 1997 as cited in Maybery et al. 2022) | ‘…evaluates an individual's methods of coping when confronted with stress in their lives’ (Maybery et al. 2022, 1254) | 28 item ‘…think about what you usually do when you are under a lot of stress…Each item says something about a particular way of coping’ rated on a 1 (Not at all) to 4 (Doing a lot) scale (Accessed from https://www.naadac.org/assets/2416/susan_shipp_ac17ho.pdf on 230829) | 25 | 1450 | |

| Fragebogen zur Erhebung der Emotionsregulation bei Kindern und Jugendlichen (Grob 2005 as cited Lochner et al. 2021) | ‘…assesses how children cope with the emotions anxiety, sadness and anger’ (Lochner et al. 2021, 7) | ‘The self-report questionnaire… consists of 90 items that assess the use of adaptive…and…maladaptive…ER strategies’ (Lochner et al. 2021, 7) | 22 | 306 | |