Social support for young people with eating disorders—An integrative review

Abstract

Eating disorder treatment should be underpinned by a recovery-oriented approach, be therapeutic, personalised and trauma informed. Within such models of care, social support is an important factor to explore in terms of its influence in supporting hope for recovery, reducing stigma, and mitigating life stressors. Limited research has been conducted to understand the types of social support that are available to young people formally diagnosed with an eating disorder, their feasibility and acceptability and the positive outcomes. This integrative review sought to explore the positive outcomes of social support or social support programs for young people with eating disorders. An integrative review was conducted based on a search of five electronic databases from inception to 31 March 2023. Methodological quality was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools and findings have been narratively synthesised and presented in accordance with the review's aims and questions. Seven studies (total 429 individuals, range 3–160) published between 2001 and 2023 were included in the final synthesis. Overall social support interventions showed promising preliminary evidence as a feasible and acceptable adjunct to treatment for young people with an eating disorder motivated to change, with some clinical improvements in psychopathology. Social support augmented existing relationships, providing a human element of open dialogue, friendship and a sense of hope for recovery. Despite the small number and heterogeneity of the studies, this review has highlighted some promising preliminary benefits. Future treatment for eating disorders should embrace adjunct modalities that enhance psychosocial recovery for young people with eating disorders.

INTRODUCTION

Global incidence rates for eating disorders are on the rise despite best efforts in treatment (Miskovic-Wheatley et al., 2023). A recent review determined the weighted means for lifetime prevalence of eating disorders for women were 8.4% (3.3%–18.6%) and 2.2% (0.8%–6.5%) for men (Galmiche et al., 2019). Initial onset generally occurs before the ages of 14 (15.8%), 18 (48.1%), 25 (82.4%) with a peak age of around 15.5 years (Solmi et al., 2022). Mortality rates are one of the highest with young people between the ages of 15 and 24 with anorexia nervosa having a 10-fold mortality risk compared to their same-aged peers (Fichter & Quadflieg, 2016; Smink et al., 2012). Treatments, such as family-based treatment, are well-established treatments for children and adolescents (Couturier et al., 2020; Crone et al., 2023; Hilbert et al., 2017; National Guideline Alliance (UK), 2017; Resmark et al., 2019), however, delays or difficulty accessing services often prolong and exacerbate the illness severity, morbidity, financial and emotional burden for individuals and their families (Hay et al., 2023).

While health services have a duty to address the needs of those in crisis, evidence shows that there is a strong case for early intervention for those of a younger age (Ackard et al., 2014; Franko et al., 2018) as a shorter duration of illness (Austin et al., 2021; Glasofer et al., 2020; Radunz et al., 2020) is crucial to more positive outcomes and better quality of life. Without early intervention, eating disorders can become more entrenched (Hamilton et al., 2022) and treatment focused solely on weight and behaviours to the detriment of psychosocial recovery is untenable (Rankin et al., 2023).

Emerging evidence suggests that treatment for eating disorders should re-focus on therapeutic alliances (Graves et al., 2017; Werz et al., 2022), person-centred and trauma-informed care (Parry et al., 2022) within a recovery-oriented approach (Hay et al., 2023). Within such models, social support is an important factor to explore in terms of its influence in supporting hope for recovery, reducing stigma, and mitigating life stressors (Leonidas & Dos Santos, 2014; Linville et al., 2012). For younger people, particularly those transitioning through adolescence, social support can be pivotal to the development of healthy relationships, improved mental health and a sense of identity (Leonidas & Dos Santos, 2014; Zhou & Cheng, 2022). The concept of social support is defined broadly as “the network of social resources that an individual perceives. This social network is rooted in the concepts of mutual assistance, guidance, and validation about life experiences and decisions. The social system plays a role in providing a number of forms of support, including informational, instrumental, and emotional support” (Zhou, 2014, p. 6161).

Social support in eating disorders can be complex and is often dependent on the type of support being offered and/or the provider's skills (Leonidas & Dos Santos, 2014). For instance, studies have shown that peer mentorship in eating disorders can provide hope for recovery (Beveridge et al., 2019; Fogarty et al., 2016; Hanly et al., 2020; Ramjan et al., 2017, 2018). Someone who understands, to talk and share with, can validate experiences and increase a sense of belonging (Fogarty et al., 2016; Ramjan et al., 2017). In contrast, other studies have identified that while social support is highly sought after, a lack of understanding from peers and parents can negatively influence eating disorder symptoms and maintenance of the illness, furthering isolation, and loneliness (Linville et al., 2012; Ma et al., 2021). Depending on healthcare providers' therapeutic skills and communication the support being provided could similarly be both helpful or hurtful (Linville et al., 2012; Ramjan & Gill, 2012).

Limited research has been conducted to understand the types of social support that are available to young people formally diagnosed with an eating disorder, their feasibility and acceptability and the positive outcomes. Given that 95% of people living with an eating disorder are under 25 years of age (McCarthy, 2022), it is important to understand social support for this age group– a high-risk group. The purpose of this integrative review was to synthesise the evidence from published research to explore the types of social support or social support programs for young people (under 25 years) with an eating disorder and the positive outcomes reported. Through a better understanding of the positive outcomes of social support/social support programs for young people with eating disorders, findings may facilitate the development of early intervention programs that include social support as an adjunct to treatment.

METHODS

- What are the characteristics (format and delivery mode) and the types of social support available to young people with eating disorders?

- What is the feasibility and acceptability of implementing social supports for young people with eating disorders?

- Do social supports promote positive outcomes for young people with eating disorders, and if so, what features are measured/reported?

Search strategy

Extensive and systematic searches were conducted across five databases—CINAHL, MEDLINE (Ovid), ProQuest Central, APA PsycINFO and Scopus—on 31 March 2023. Prior to this, key search terms were identified in consultation with a specialist University librarian. Based on the consultation process, a concept map was created that categorised terms under three main concepts: Social support program; Young person (<25 years) and Eating Disorder. The final combination of key search terms and medical subject headings (MeSH) used depending on the database being searched. An example of the final search terms for CINAHL were as follows:

(MH “Support, Social+”) OR social support OR psychosocial support OR social behaviour OR prosocial behaviour OR peer support OR peer counsel* OR mentor* OR support group OR support program OR support network OR support meeting OR support intervention AND (MH “Child+”) OR (MH “Adolescence+”) OR (MH “Young Adult”) OR child* OR teen* OR adolescen* OR young* person* OR young* people OR young* adult* OR emerging adult* AND (MH “Eating Disorders+”) OR eating disorder* OR disordered eating OR feeding disorder* OR anorexi* OR bulimi* OR orthorexi* OR bing* OR purg* OR avoidant restrictive food intake OR ARFID OR pica. The full search strategy for each database is provided in Table 1. In addition, handsearching and forward/backward screening of the reference list within all retrieved full-texts studies was undertaken.

| Database | Concept: Social Support Program | Concept: Young Person (<25 years) | Concept: Eating Disorder |

|---|---|---|---|

| CINAHL | (MH “Support, Social+”) OR social support OR psychosocial support OR social behaviour OR prosocial behaviour OR peer support OR peer counsel* OR mentor* OR support group OR support program OR support network OR support meeting OR support intervention | (MH “Child+”) OR (MH “Adolescence+”) OR (MH “Young Adult”) OR child* OR teen* OR adolescen* OR young* person* OR young* people OR young* adult* OR emerging adult* | (MH “Eating Disorders+”) OR eating disorder* OR disordered eating OR feeding disorder* OR anorexi* OR bulimi* OR orthorexi* OR bing* OR purg* OR avoidant restrictive food intake OR ARFID OR pica |

| APA PsycINFO | social support OR psychosocial support OR social behaviour OR prosocial behaviour OR peer support OR peer counsel* OR mentor* OR support group* OR support program* OR support network* OR support meeting* OR support intervention* | child* OR teen* OR adolescen* OR young* person* OR young* people OR young* adult* OR emerging adult* | eating disorder* OR disordered eating OR feeding disorder* OR anorexi* OR bulimi* OR orthorexi* OR bing* OR purg* OR avoidant restrictive food intake OR ARFID OR pica |

| ProQuest Central | noft(social support OR psychosocial support OR social behaviour OR prosocial behaviour OR peer support OR peer counsel* OR mentor* OR support group* OR support program* OR support network* OR support meeting* OR support intervention*) | noft(child* OR teen* OR adolescen* OR young* person* OR young* people OR young* adult* OR emerging adult*) | noft(eating disorder* OR disordered eating OR feeding disorder* OR anorexi* OR bulimi* OR orthorexi* OR bing* OR purg* OR avoidant restrictive food intake OR ARFID OR pica) |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY (“social support” OR “psychosocial support” OR “social behaviour” OR “prosocial behaviour” OR “peer support” OR “peer counsellor” OR “peer counselling” OR mentor* OR “support group” OR “support program” OR “support network” OR “support meeting” OR “support intervention”) | TITLE-ABS-KEY (child* OR teen* OR adolescen* OR “young person” OR “younger person” OR “young people” OR “younger people” OR “young adult” OR “younger adult” OR “emerging adult”) | TITLE-ABS-KEY (“eating disorder” OR “disordered eating” OR “feeding disorder” OR anorexi* OR bulimi* OR orthorexi* OR bing* OR purg* OR “avoidant restrictive intake” OR arfid OR pica) |

| MEDLINE (Ovid) | exp Social Support/or (social support or psychosocial support or social behaviour or prosocial behaviour or peer support or peer counsel* or mentor* or support group or support program or support network or support meeting or support intervention).mp. | exp child/or adolescent/or young adult/or (child* or teen* or adolescen* or young* person* or young* people or young* adult* or emerging adult*).mp. | exp “Feeding and Eating Disorders”/or (eating disorder* or disordered eating or feeding disorder* or anorexi* or bulimi* or orthorexi* or bing* or purg* or avoidant restrictive food intake or ARFID or pica).mp. |

Eligibility criteria

Population

Studies had to include individuals aged <25 years or a mean cohort age <25 years and formally diagnosed with an eating disorder as per the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM) (American Psychiatric Association, 2022) or international classification of diseases (ICD) (World Health Organization, 2021) criteria.

Intervention

No limitations were placed on the type of social support intervention or program. Social support in this context has been defined broadly as an inherent occurrence resulting from “the network of social resources that an individual perceives. This social network is rooted in the concepts of mutual assistance, guidance, and validation about life experiences and decisions. The social system plays a role in providing a number of forms of support, including informational, instrumental, and emotional support” (Zhou, 2014, p. 6161). In this review, social support interventions or programs had to be standalone or an adjunct to inpatient, outpatient, partial hospital programs, services, or treatments and could also include organic social support within interpersonal relationships that may have been identified as a theme within studies. While we acknowledge that some highly structured treatment modalities, including Family-Based treatment, integrate social support as a central tenet to facilitating positive outcomes, these were excluded to focus on the impact of social support independent of formal programs.

Outcome

The outcome was to identify and evaluate the acceptability/feasibility of the social support intervention or program and determine the positive outcomes for young people with an eating disorder.

Study design

All peer-reviewed primary research (including theses/dissertations) and all study types were included in this review. No limitations were placed on study quality, location or date of publication, but studies had to be written in the English language.

Study selection

All articles retrieved through database searching were imported into Endnote 20 (referencing software) where duplicates were removed. Title and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers (BS & LR) and the same reviewers screened full-text articles. A third reviewer (SP) was consulted to resolve any disagreements. For any articles, where clarification was required to determine whether papers met the inclusion criteria, both email and social media was used to try and contact one or more author/s. Eight authors were contacted and six replied to our enquires. For the studies where confirmation from authors was not possible, one study was excluded as both age and clinical diagnosis could not be confirmed and one study in an inpatient setting was included as it was assumed a formal clinical diagnosis should have been made. Forward and backward searching of the reference lists was conducted by one reviewer (BS).

Data extraction

Articles included in the review were divided among two study authors (BS & LR) for independent data extraction. The data extraction table included the following: Author/Year/Country; Aim, Study design; Study setting, Sample characteristics, Instruments/measurements; Social support characteristics, Intervention characteristics; Significant outcomes/findings and Conclusions.

Quality assessment

Each article included in the review was appraised for methodological quality using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Tools (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2020). These tools were chosen due to the heterogeneity of study designs within the included studies. The following JBI tools were accessed to assess the risk of bias and quality of each study: Qualitative research, Analytical cross-sectional studies, Quasi-experimental studies, Case reports and Randomised controlled trials. The quality assessment scoring was undertaken by two reviewers (BS & LR) independently and where consensus was not met, a third reviewer (SP) was engaged to make the final determination. The third reviewer was blind to the identity of who conducted the initial assessments. Terms such as ‘yes’, ‘unclear’ and ‘no’ were used to describe how well studies met each criterion and each was rated a score of 1, 0, 0, respectively, with a final percentage calculated. No study was excluded based on this rating.

RESULTS

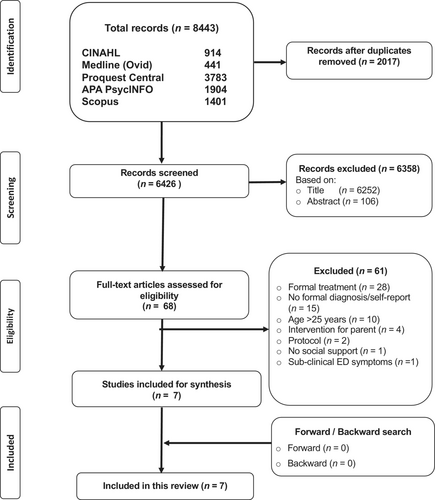

Following a rigorous and systematic search of each of the five electronic databases, all articles retrieved (n = 8443) were exported into Endnote 20, where any duplicates (n = 2017) were removed. Titles, followed by abstracts were then screened against the inclusion criteria. Following this initial screening of title and abstract, a further 6358 articles were excluded. No further articles were found through forward or backward screening. The full text of the remaining 68 articles were then screened and reviewed independently by two reviewers (LR & BS). Of these 68 articles, reasons for exclusion included, a formal treatment modality (n = 28), no formal diagnosis/self-report or retrospective account (n = 15), age > 25 years (n = 10), intervention for parents (n = 4), protocol (n = 2), no social support reported (n = 1), sub-clinical eating disorder symptoms (n = 1). A final 7 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review. See Figure 1 for further detail regarding the search and screening process.

General overview

Of the seven studies included in this review, two originated from Spain (Lázaro et al., 2011; Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009), two from the United Kingdom (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Tierney, 2008), one from Ireland (Monaghan & Doyle, 2023) and two from the United States of America (Scott Richards et al., 2006; Yager, 2001). Two of the studies used a cross-sectional survey design (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009), two employed qualitative research (Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Tierney, 2008), and one study each used a quasi-experimental (Lázaro et al., 2011), randomised controlled trial [RCT] (Scott Richards et al., 2006) and case report (Yager, 2001) design. Participants were from a range of study settings, including day hospital treatment (Lázaro et al., 2011), inpatient treatment (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Scott Richards et al., 2006; Tierney, 2008), outpatient treatment (Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009; Yager, 2001) or self-help group (Tierney, 2008). The youngest participant was 11 years of age (Tierney, 2008). Ages ranged from 13 to 18 years (Lázaro et al., 2011; Monaghan & Doyle, 2023), 12 to 20 years (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016), 12 to 34 years (Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009), 13 to 52 years (Scott Richards et al., 2006), 11 to 18 years (Tierney, 2008) and 17 to 22 years (Yager, 2001) with all mean cohort age under 25 years. Sample sizes across the seven studies ranged from 160 participants (Lázaro et al., 2011) in the quasi-experimental study to 4 participants (Yager, 2001) in the case reports, although only 3 of the 4 case reports that met our age criteria have been included in this review. Most studies included females only (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009; Scott Richards et al., 2006; Yager, 2001) except for two, with one including nine (Lázaro et al., 2011) and the other one male (Tierney, 2008). Five studies had formally diagnosed participants using DSM criteria (Lázaro et al., 2011; Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009; Scott Richards et al., 2006; Yager, 2001), one used the ICD criteria (Monaghan & Doyle, 2023) and one did not mention the criteria used although the diagnosis would presumably have been made using one of the diagnostic criteria as participants had been in inpatient treatment (Tierney, 2008). Four studies reported specific social support interventions within a group setting (Lázaro et al., 2011; Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Scott Richards et al., 2006) or individual asynchronous communication by email (Yager, 2001), the rest reported social support within existing relationships (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009; Tierney, 2008). Studies were published between 2001 (Yager, 2001) and 2023 (Monaghan & Doyle, 2023). See Table 2 for summary of included studies.

| Author, year, country | Aim, Study design | Study setting, Sample characteristics, Instruments/Measurements | Social support characteristics, Intervention characteristics | Significant outcomes/findings | Conclusions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Lázaro et al. (2011) Spain |

Aim: To evaluate changes in self-esteem and social skills in adolescent patients with eating disorders following group therapy. Study design: Quantitative (Quasi-experimental). |

Study setting: Day hospital treatment program. Sample characteristics: N = 160 young people aged 13 to 18 years (M = 15.5, SD = 1.2) with a DSM-IV diagnosis of an eating disorder. In total, there were n = 151 female and n = 9 male participants divided into two subgroups:

Instruments/Measurements:

|

Social support characteristics: N/A. Intervention characteristics: Two concurrent group therapy sessions: one program related to self-esteem and one program related to social skills. Each program comprised eight sessions which were conducted weekly and lasted 90 min per session. Led by clinical psychologists. |

AN-rd demonstrated higher global self-esteem than BN-rd as measured by the PHC-SCS (effect size = 0.083) and the SEED (effect size = 0.038) but no differences in social skills were identified using the Socialisation Battery (effect size = 0.054). Positive changes in social skills were observed in BN-rd in comparison with AN-rd (effect size = 0.074). For self-esteem, both groups showed significant improvements in perception of physical appearance, self-concept related to weight and shape, self-concept related to others, and happiness and satisfaction post-intervention, and the BN-rd group also showed significant improvements in perception of intellectual and school status, freedom from anxiety and popularity. For social skills, both groups showed significant improvements in social withdrawal and leadership post-intervention, and the BN-rd group also showed significant improvement in social anxiety/shyness. Clinical improvement in self-esteem was positively correlated with age in AN-rd. |

A group therapy programme is an effective way to increase self-esteem and social skills in adolescents with eating disorders. Greater social competence could promote the formation of positive peer relationships during a critical period of social–emotional development and help reduce chronicity and risk of relapse. |

| 2 |

Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al. (2016) United Kingdom |

Aim: To investigate the relationship between motivation to change and the quality of friendships between young people with AN. Study design: Quantitative (Cross-sectional). |

Study setting: Three specialist inpatient units. Sample characteristics: N = 30 young people aged 12 to 20 years (M = 15.07, SD = 1.68). All participants were female with a DSM-IV diagnosis of AN. Instruments/Measurements:

|

Social support characteristics: Friendships between young people on the ward (questionnaires completed based on best female friend on the ward). Intervention characteristics: N/A. |

When controlling for age motivational stage of change was positively correlated with Self-Validation, Intimacy and Help. No association was observed between BMI centile and any of the friendship quality and satisfaction subscales (for all correlations, rs N −0.20 and b 0.11, p N 0.291). Positively significant association was reported between age with MFQ-RA (rs = 0.44, p = 0.015) and MFQ-FF Self-Validation (rs = 0.37, p = 0.048) with trends for MFQ-FF Companionship (rs = 0.33, p = 0.080) and Reliability subscales (rs = 0.34, p = 0.065). Sharing was an important treatment support (“I share my anorexic ideas and feelings about eating with my friends”). Young people rated friends on the ward and family as the most helpful in following their treatment plan. Having friends who would help when it became hard to follow a treatment programme and avoid “giv[ing] in” to anorexia was significantly positively associated with MFQ-RA Positive Feelings/Satisfaction (rs = 0.43, p = 0.021 and rs = 0.58, p = 0.003, respectively) and all subscales of the MFQ-FF (for both items across all subscales, rs N 0.37, p < 0.046). |

Higher motivational stage of change was reflected in higher quality of friendships/support. Intimacy and self-validation (listening, agreeing, encouraging and helping to achieve goals) correlated with greater motivation. Therefore, friendships and the social support they provide could increase motivation and improve psychosocial outcomes. |

| 3 |

Monaghan and Doyle (2023) Ireland |

Aim: To explore the experiences of young people with AN during mealtimes and a post-meal support group. Study design: Qualitative (Descriptive). |

Study setting: Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service inpatient unit. Sample characteristics: N = 6 young people aged 13 to 18 years. All participants were female with an ICD diagnosis of AN. Instruments/Measurements: Semi-structured telephone interviews of young people with AN who had attended at least one post-meal support group. |

Social support characteristics: N/A. Intervention characteristics: Post-meal support group facilitated by mental health nurses. Each session lasted 30 min and comprised a recovery-focused discussion (share thoughts and provide peer support) followed by distraction activities. The session starts with taking an item from a soothe box (i.e., stress ball, fidget toy)—to self-soothe. |

Mealtimes and post-mealtimes were emotional and distressing times for young people, involving negative ED cognitions that resulted in comparisons with others, adopting new disordered eating behaviours, and engaging in body checking and compensatory behaviours. Being with nursing staff was reassuring and “general chats” were an effective distraction technique that helped normalise their experience. All participants felt that the post-meal support group had a positive impact on their recovery (structure and routine). When a rapport was established with nursing staff, they could confide in them. Hearing from other young people at different stages in their recovery was motivational, and it normalised and validated individual's experiences. Using items from a soothe box—such as fidget toys—while participating in distraction activities alleviated ED cognitions and prevented engagement in compensatory behaviours like exercising and purging. Participants felt there was inconsistency in the delivery of post-meal support groups across different staff members which provoked feelings of uncertainty and anxiety. Participants also feared that they would trigger others and/or be triggered by others when voicing negative thoughts, feelings, and emotions. |

A post-meal support group offers a secure, structured, and consistent environment at a time of great distress for young people with eating disorders, although to ensure effectiveness, clinicians delivering the intervention require adequate training and support. |

| 4 |

Quiles Marcos and Terol Cantero (2009) Spain |

Aim: To assess social support elements (providers, satisfaction and support actions) in patients with an ED in relation to diagnosis, sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and self-concept. Study design: Quantitative (Cross-sectional). |

Study setting: Outpatient treatment from an eating disorder unit. Sample characteristics: N = 98 young people aged 12 to 34 (M = 20.8, SD = 5.61). All participants were female with a DSM-IV-R diagnosis of an eating disorder. AN (n = 60); BN (n = 27); UFED (n = 11). Duration of ED: 1 month-20 years (M = 45.58 months, SD = 45.52). Duration of treatment: 1 month-5 years (M = 16.86 months, SD = 17.69). Comorbidities: Affective disorder (14.3%); anxiety (14.3%); substance abuse (6.1%). Instruments/Measurements:

|

Social support characteristics: Providers of support: Partner, mother, father, children, siblings, work colleagues or classmates, neighbours, friends, doctors and nurses. Types of support: Emotional (e.g., visiting, accompanying, entertaining), informational (e.g., advising, listening, guiding) and practical (e.g., actions/services/doing tasks). Support actions: Listening, encouraging, entertaining, advising, visiting, doing jobs, financial assistance, accompanying, other ways. Intervention characteristics: N/A. |

Main providers Family network: Mothers (87.6%) followed by partners (73.1%) main providers of social support. Professional network: Doctors (80.6%) and nurses (66.1%). Social network: Friends (70.4%). Range of providers: 1–10 (M = 5.2, SD = 2). AN more providers than BN. Satisfaction with support: High (M = 3.99, SD = 0.78), particularly from mothers (family network) and partners (nuclear network). No differences between AN and BN on satisfaction. Types of support: Greater informational support (listening, encouraging and advising) than emotional and practical support. Frequency: informational support followed by emotional = most frequent support. Mother provides most actions (M = 7.2, SD = 4.09) followed by father (M = 4.11, SD = 4.21). AN received more support actions than BN (t = 2.86, p < 0.01, d = 0.60), and accompanying (t = 2.18, p < 0.05, d = 0.45) than bulimics. Younger patients 16–23 years received more support actions from mothers. Self-concept: Greater family self-concept = greater number of support providers (t = −2.33, p < 0.05) and more informational support (t = −3.25, p < 0.05). Comorbidity: patients with anxiety crisis received less support actions from their parents (t = 1.98, p < 0.05; d = 0.56), and more from the nursing staff (t = 2.62, p < 0.01; d = 0.74). Substance abuse disorder patients received more informative and practical support (t = 3.12, p < 0.01; d = 1.27; t = 2.49, p < 0.05; d = 1.02), more support actions from their partners (t = 2.59, p < 0.05; d = 1.06), from the doctor (t = 2.74, p < 0.05; d = 1.12), and from the nursing staff (t = 3.55, p < 0.001; d = 1.45). |

Family networks (particularly mothers) important in ED social support. Satisfaction with support and informational support were high—being listened to, encouraged, informed and advised was received most frequently. Greater family self-concept = greater number of support providers and more support received. Training to improve social skills and communication may broaden individuals' social networks beyond the family. |

| 5 |

Scott Richards et al. (2006) United States of America |

Aim: To evaluate the effectiveness of a spiritual support group compared to a cognitive and emotional support group for eating disorders. Study design: Quantitative (Randomised controlled). |

Study setting: Private inpatient unit for eating disorders. Sample characteristics: N = 122 people aged 13–52 years (M = 21.2, SD = 6.6). All participants were female with a DSM-IV diagnosis of an eating disorder. AN (n = 42); BN (n = 47); EDNOS (n = 33) Religion: Latter Day Saints (n = 84); Protestant (n = 8); Catholic (n = 7); Jewish (n = 2); Other (n = 9); no religion (n = 9). Average length of stay ED treatment program: 68 days. Instruments/Measurements:

|

Social support characteristics: N/A. Intervention characteristics: Spirituality Group: read ‘Spiritual renewal: A journey of faith and healing’ (self-help book); attended a weekly 1-h group session with a group leader and others to share learnings. Cognitive Group: read ‘Mind over mood: Change how you feel by changing the way you think’ (self-help book); attended a weekly 1-h group session with a group leader and others to share learnings. Emotional Group: attended a weekly 1 h “open topic” discussion, with a group leader and others, to discuss elements within the program (self-esteem, nutrition). |

Reported very large effect size on all outcome measures as listed below:

|

While the spiritually oriented intervention enhanced treatment outcomes (reduction in depression and anxiety, relationship distress, social role conflict and ED symptoms) it must be noted that there were only small to moderate effect size differences between treatment groups. The sample size was small, treatment fidelity issues with a high proportion of Latter-Day Saints. |

| 6 |

Tierney (2008) United Kingdom |

Aim: To explore treatment experiences in anorexia nervosa from the perspective of young people. Study design: Qualitative. |

Study setting: Inpatient adolescent psychiatric unit (n = 6) and external self-help group (n = 4). Sample characteristics: N = 10 young people aged 11–18 years (M = 17, SD = 1.8). Nine participants were female and 1 male with restrictive (50%) and bulimic (50%) sub-type AN. Median length of time since ED diagnosis: 24 months (range 6 to 60 months). Treatment stage at interview: 4 inpatients, 3 outpatients, 3 no longer in treatment. Instruments/Measurements: Semi-structured interviews lasting between 40 min to 2 h. |

Social support characteristics: Parents, siblings, others with an eating disorder (non-professional). Nurses, doctors, counsellors, social worker, child and adolescent mental health team (professional). Intervention characteristics: N/A. |

Family first to recognise the need for professional help. General practitioners often failed to diagnose ED and other practitioners focused on food and weight gain. On general wards staff were dismissive and “didn't have time to listen”. Within specialist care felt there was an over-emphasis on weight gain without consideration for psychological support and a high turnover of therapists with nursing staff unable to delve deeper. Qualities in professionals they wanted included knowledge of the condition, a person-centred approach and sensitivity. Support from peers on an ED unit could be positive and negative—a negative competitive element but also motivation to recover; confiding in each other. Parents, mostly mothers, were seen by some as vital support. Others found parents to be untrusting and angry at ED behaviour. Siblings were support and motivation to recover for some but AN could also cause sibling relationships to fracture. Some received social support from others with an ED at self-help groups where they saw different stages of recovery. Recovery—discussed having the right mindset and intrinsic motivating factors to change. Treatment did not support socialisation skills (building self-confidence & self-esteem) to re-engage in social activities and social life. |

Equal attention needs to be paid to restoration of both the physical and the psychosocial–particularly supporting social skill development and peer relationships in the community. Non-professional support was valued as was a connection with someone who listened, had empathy and understood them. |

| 7 |

Yager (2001) United States of America |

Aim: To explore the use of email as an adjunct to treatment for anorexia nervosa. Study design: Case reports. |

Study setting: Outpatient treatment. Sample characteristics: Case 1: 17 year old female; duration AN = 3–4 years; training to be athlete since age 8 years. Almost daily email messages. Few social invitations. Case 2: 18 year old female; to start University; duration of AN = 2 years. Weekly email messages. Case 4: 22 year old female; recovering from severe AN. Frequent email while transitioning to a new psychiatrist. All participants were female with a DSM diagnosis of an eating disorder. Instruments/Measurements:

|

Social support characteristics: N/A. Intervention characteristics: Individual treatment plans accompanied by mandatory email reports of ED behaviours. Office visits ranged from weekly to every few months. Email contact ranged from one to several times a week. Patients had contact with other providers. |

Good clinical improvement. On the whole patients perceived the use of email to be beneficial as motivational support—good acceptability and adherence. Email benefits: asynchronous ‘therapeutic’ contact with a clinician allows trust to grow (person-centred care), ability to “talk” about life on demand (someone ‘real’ listening), pushed to confront their eating behaviours/choices, integrity, and honesty. Limited clinician time needed. Email negatives: extra thing to do (sometimes forget), having to report bad news, a ‘forced’ check-in. | Email allows for the development of trust and therapeutic relationships providing motivational support and counsel. The young person can initiate contact and determines the level of disclosure. Informed consent, confidentiality, professional ‘netiquette’, email response time, and safety to be negotiated within this modality. |

- Abbreviations: AF-5, Autoconcepto Forma 5; AN, Anorexia Nervosa; BAS-3, Socialisation Battery; BN, Bulimia Nervosa; BSQ, Body Shape Questionnaire; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; EASP, The Escala de Apoyo Social Percibido; EAT, Eating Attitudes Test; ED, Eating Disorder; EDNOS, Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified; EDSMS, Eating Disorder Self-Monitoring Scale; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; MFQ-FF, McGill Friendship Questionnaire Friend's Function; MFQ-RA, McGill Friendship Questionnaire Respondent's Affection; MSCARED, Motivational Stages of Change for Adolescents Recovering from an Eating Disorder; MSEI, Multidimensional Self-Esteem Inventory; OQ-45, Outcome Questionnaire; PHC-SCS, Piers-Harris Children's Self Concept Scale; SEED, Self-Esteem in Eating Disorders Questionnaire; SWBS, Spiritual Wellbeing Scale; TSOS, Theistic Spiritual Outcome Survey; UFED, Unspecified Feeding or Eating Disorder.

Quality appraisal

A methodological quality score was calculated as a percentage for each study, with a score greater than 80% rated as high quality, 60%–79% rated as moderate quality and 30%–59% as poor quality (Villarosa et al., 2019). Two of the seven studies were rated as high (Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Yager, 2001) for their design and methodology, four as moderate (Lázaro et al., 2011; Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009; Tierney, 2008) and one as weak (Scott Richards et al., 2006). See Table 3 for quality ratings for all studies.

| Randomised control trial | Scott Richards et al. (2006) | Qualitative | Monaghan and Doyle (2023) | Tierney (2008) | Quasi-experimental | Lázaro et al. (2011) | Cross-sectional studies | Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al. (2016) | Quiles Marcos and Terol Cantero (2009) | Case report | Yager (2001) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Was true randomization used for assignment of participants to treatment groups? | No | 1. Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology? | Yes | No | 1. Is it clear in the study what is the ‘cause’ and what is the ‘effect’ (i.e. there is no confusion about which variable comes first)? | Yes | 1. Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? | Yes | Yes | 1. Were patient's demographic characteristics clearly described? | Yes |

| 2. Was allocation to treatment groups concealed? | No | 2. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives? | Yes | Yes | 2. Were the participants included in any comparisons similar? | No | 2. Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? | Yes | Yes | 2. Was the patient's history clearly described and presented as a timeline? | Yes |

| 3. Were treatment groups similar at the baseline? | Unclear | 3. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data? | Yes | Yes | 3. Were the participants included in any comparisons receiving similar treatment/care other than the exposure or intervention of interest? | No | 3. Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | Yes | 3. Was the current clinical condition of the patient on presentation clearly described? | Yes |

| 4. Were participants blind to treatment assignment? | No | 4. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data? | Yes | Yes | 4. Was there a control group? | No | 4. Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition? | Yes | Yes | 4. Were diagnostic tests or assessment methods and the results clearly described? | Unclear |

| 5. Were those delivering the treatment blind to treatment assignment? | No | 5. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results? | Yes | Yes | 5. Were there multiple measurements of the outcome both pre and post the intervention/exposure? | Yes | 5. Were confounding factors identified? | No | No | 5. Was the intervention(s) or treatment procedure(s) clearly described? | Yes |

| 6. Were treatment groups treated identically other than the intervention of interest? | Yes | 6. Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically? | No | No | 6. Was follow-up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow-up adequately described and analysed? | Yes | 6. Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | No | No | 6. Was the post-intervention clinical condition clearly described? | Yes |

| 7. Were outcome assessors blind to treatment assignment? | Unclear | 7. Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice-versa, addressed? | No | Yes | 7. Were the outcomes of participants included in any comparisons measured in the same way? | Yes | 7. Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | Yes | 7. Were adverse events (harms) or unanticipated events identified and described? | Yes |

| 8. Were outcomes measured in the same way for treatment groups? | Yes | 8. Are participants and their voices adequately represented? | Yes | Yes | 8. Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? | Yes | 8. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Yes | Yes | 8. Does the case report provide takeaway lessons? | Yes |

| 9. Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? | Unclear | 9. Is the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, and is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body? | Yes | Unclear | 9. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Yes | |||||

| 10. Was follow-up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow-up adequately described and analysed? | Yes | 10. Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data? | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| 11. Were participants analysed in the groups to which they were randomised? | Yes | ||||||||||

| 12. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Yes | ||||||||||

| 13. Was the trial design appropriate and any deviations from the standard RCT design (individual randomisation, parallel groups) accounted for in the conduct and analysis of the trial? | No | ||||||||||

| Total (max 13) | 38.5% | Total (max 10) | 80% | 70% | Total (max 9) | 66.7% | Total (max 8) | 75% | 75% | Total (max 8) | 87.5% |

Format and delivery of social supports

At the time of receiving treatment for an eating disorder, the young people included in the studies were admitted to an inpatient unit (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Scott Richards et al., 2006; Tierney, 2008), engaging with outpatient services (Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009; Yager, 2001), or attending a day hospitalisation program (Lázaro et al., 2011). Yager (2001) was the only study that did not present a face-to-face intervention, instead using email correspondence as a therapeutic adjunct to routine psychiatric care. Of the six remaining studies, three reported a group-based intervention (Lázaro et al., 2011; Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Scott Richards et al., 2006), although there were no shared features in their design. Lázaro et al. (2011) delivered a structured program comprising 8 weeks of 90-min therapy sessions to improve self-esteem and social skills, while Monaghan and Doyle (2023) delivered a 30-min post-meal support group aimed at minimising distress and disordered cognition/behaviour. The treatment groups reported by Scott Richards et al. (2006) were divided into spiritual-, cognitive-, and emotion-based education with weekly sessions lasting 60 min. All interventions were facilitated by mental health nurses (Monaghan & Doyle, 2023), psychologists (Lázaro et al., 2011; Scott Richards et al., 2006), or a psychiatrist (Yager, 2001). The three studies that did not deliver an intervention explored perceptions of social support within existing relationships and experiences of young people when receiving treatment for an eating disorder (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009; Tierney, 2008).

Acceptability of social support

Young people perceived social support to have a positive impact on their recovery and the effect was attributed to experiences with peers (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Tierney, 2008), family (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009; Tierney, 2008), and healthcare professionals wherein the therapeutic relationship was characterised by open dialogue and increased self-disclosure (Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Yager, 2001). The opportunity to engage with young people at different stages of recovery (Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Tierney, 2008) and motivational stages of change (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016) facilitated positive perceptions of social support as young people were able to provide help and be helped in return, which created a sense of purpose. Regarding family, mothers, siblings and partners were specifically identified as providers of informational, instrumental, and emotional support (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009; Tierney, 2008).

Nonetheless, a consequence of group-based interventions, identified in the qualitative studies, was the potential for young people to engage in harmful behaviours by comparing themselves to their peers (Monaghan & Doyle, 2023), or to trigger and be triggered by others when sharing negative thoughts (Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Tierney, 2008). Another barrier to treatment success was young peoples' dissatisfaction with professionals' and programs' fixation on clinical outcomes—namely, weight gain—instead of meaningful mental health improvement (Tierney, 2008).

Feasibility of social support

Variability in healthcare providers' knowledge, skills and attitudes challenged the effective delivery of social support interventions. Regular meetings were held between the principal investigator and group therapy leaders in Scott Richards et al. (2006) in an attempt to maintain adherence to treatment protocols, however Monaghan and Doyle (2023) and Tierney (2008) identified through patient statements that inconsistency in healthcare professionals' clinical experience and support delivery undermined the therapeutic relationship and negatively impacted recovery progress. Additionally, where social support is being delivered by healthcare professionals, the inherent power imbalance can affect the therapeutic relationship—“when I came to you, you had the upper hand” (Yager, 2001).

Despite the general absence of withdrawn participants and loss to follow-up, Lázaro et al. (2011) was the only study that claimed their large sample size was a strength. Instead, smaller sample sizes were identified as a limitation in several studies (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Scott Richards et al., 2006) and Tierney (2008) further noted the underrepresentation of young men with eating disorders and potential lack of generalisability given both the homogeneity of their sample's sociodemographic characteristics and heterogeneity of eating disorder diagnoses and psychopathology. Quiles Marcos and Terol Cantero (2009) reinforce the latter point emphasising that the findings are relevant to the niche sample of young people with eating disorders being studied. Furthermore, while Scott Richards et al. (2006) and Quiles Marcos and Terol Cantero (2009) reported the incidence and impact of other mental health diagnoses—for example, depression and anxiety—in their patient populations, this was not considered in all studies.

Social support measurements

Outcomes were measured using validated tools in four studies (Lázaro et al., 2011; Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009; Scott Richards et al., 2006) however, each differed. For example, self-esteem was measured using the Self-Esteem in Eating Disorders Questionnaire (SEED) in the study by Lázaro et al. (2011) and Multidimensional Self-Esteem Inventory (MSEI) in the study by Scott Richards et al. (2006). While self-concept was measured with the Piers-Harris Children's Self-Concept Scale (PHC-SCS) in the study by Lázaro et al. (2011) and the Autoconcepto Forma 5 (AF-5) Questionnaire in the study by Quiles Marcos and Terol Cantero (2009). Three of the studies measured social skills and behaviour (BAS-3) (Lázaro et al., 2011), friendship quality and satisfaction with friendships (MFQ) (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016) and more specifically social support (EASP) and satisfaction with support (Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009). Five studies included sociodemographic and clinical data (Lázaro et al., 2011; Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009; Scott Richards et al., 2006; Yager, 2001) with others evaluating or monitoring eating disorder symptoms (Lázaro et al., 2011; Scott Richards et al., 2006), body shape concerns (Scott Richards et al., 2006), distress, interpersonal and social functioning (Scott Richards et al., 2006), spiritual wellbeing (Scott Richards et al., 2006) and motivation to change (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016). Three studies (Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Tierney, 2008; Yager, 2001) provided qualitative comments to illustrate positive outcomes of social support which included increased self-esteem, motivation to change and reduced symptoms.

Intervention outcomes

All seven studies demonstrated some improvements as a result of the intervention or social support in the following areas: self-esteem (Lázaro et al., 2011; Scott Richards et al., 2006; Yager, 2001), social skills (Lázaro et al., 2011), self-concept (Lázaro et al., 2011; Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009), motivation to change (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Tierney, 2008; Yager, 2001), spiritual well-being (Scott Richards et al., 2006) and reduced psychopathology (Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Scott Richards et al., 2006; Yager, 2001). Lázaro et al. (2011), a quasi-experimental (pre-post) study (N = 160), reported significant improvements in self-esteem and social skills for both their groups (AN-related disorders and BN-related disorders). Of note, social behaviours including leadership improved as did social withdrawal and isolation, with participants with bulimia nervosa also demonstrating less anxiety/shyness in social relationships. Similarly Scott Richards et al. (2006), a randomised controlled trial study (N = 122), found that support groups, no matter the type of support being offered, all improved outcome measures in the first 8 weeks. However, it should be noted that self-esteem improvement did not significantly differ across the three treatment conditions (two of which, while group-based, do not appear to have strongly encouraged supportive sharing rather suggest that participants shared what they learned from the assigned readings) (Scott Richards et al., 2006). Notwithstanding the need for motivation to change, the qualitative study (N = 10) by Tierney (2008) illustrated an absence of capacity building for young people during treatment to confidently re-engage in social activities and life in general—“to start doing things that people my age do”.

The quality of friendships and peer support onwards and the ability to share thoughts with friends was an invaluable treatment support that enhanced motivation to change, with the potential to reduce psychopathology and improve psychosocial outcomes (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016). Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al. (2016), a cross-sectional study (N = 30), reported friends (and family) were rated as the most helpful in supporting young people to comply with treatment and “not to give in to my Anorexia” by being present to listen, validate and encourage to meet goals. In addition, Quiles Marcos and Terol Cantero (2009), a cross-sectional study (N = 98), identified family (primarily mothers—87.6%) were the main providers of social support for patients with an eating disorder and more so for the younger patients, with friends still highly ranked (70.4%) and nurses ranked a little lower (66.1%).

Satisfaction with the support received in the study by Quiles Marcos and Terol Cantero (2009) was high, with informational support (i.e., receiving advice/guidance, being encouraged/listened to) received most often and those with greater family self-concept receiving support from more providers (Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009). Tierney (2008) reported family members could be either positive or negative support providers. From a positive perspective, mothers were again described as vital support for some—“I think the main thing has been my mum. If it wasn't for her…she was just there, she was going through it with me…” and “My mum was the only person I could talk to…”. Furthermore, siblings also provided young people with the motivation to recover—“I had a beautiful letter from my sister…she needed me to be there for her…from then on, I started to think… ‘I don't want to live like this’…” (Tierney, 2008).

The qualitative studies provided further support for the positive benefits of individual or group social support. For example, Monaghan and Doyle (2023), a qualitative study (N = 6), highlighted that post-meal support groups were helpful to recovery by providing distraction (through conversation and activities) to alleviate eating disorder cognitions and prevent engagement in compensatory behaviours. Having nursing staff present and a structured routine was comforting and once a relationship was established, it was easier for them to open up about their feelings—“it was ok to say I'm having a bad day, or I'm really fed up or angry” (Monaghan & Doyle, 2023). In contrast, participants in the study by Tierney (2008) reported that staff in general wards were often dismissive, lacked knowledge and “didn't have time to listen” and on specialist wards, there was an over-emphasis on weight without due consideration for psychosocial recovery. Young people expressed a desire for healthcare professionals to be knowledgeable towards their lived experience and take a person-centred approach to care, rather than invalidating their experience—“I was told to eat more”. With the high turnover of therapists, one participant wanted the support from nursing staff to be more than superficial banter—“It was always just ‘and how has your week been?’… I would have liked it go deeper” (Tierney, 2008).

Hearing from peers further in their recovery was motivating and provided a sense of hope (Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Tierney, 2008)—“if they can do it, I can do it” (Monaghan & Doyle, 2023) and being able to express feelings to others who understood was validating and normalised the experience—“knowing you're not alone” (Monaghan & Doyle, 2023) and “only those with anorexia could fully appreciate what they were going through” (Tierney, 2008). In addition, Yager (2001), a series of case reports (N = 3), showed that email communication provided individual, personalised, asynchronous motivational support which increased self-esteem, allowed for trust (e.g., less formality—“Hi Dr. Yager-meister!”, “Hey Dr. Y!”, “Hey, Dr. Dude”) and a therapeutic relationship to develop with overall improved psychopathology. Most young people appreciated the opportunity to express their thoughts and feelings honestly and openly, to “talk” on demand (just-in-time support) and to determine the level of disclosure with someone ‘real’ listening—“Thanx for reading (listening sorta). I'll talk to you more on Thursday. Bye-bye. S” (Yager, 2001). While the email communication may have revolved around eating disorder behaviours, weight and food, these were individual (between psychiatrist and patient) and non-triggering (Yager, 2001), while with peer support these types of conversations were often triggering (Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Tierney, 2008) due to a competitive element or sharing of negative thoughts.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this review was to explore the types of social support available for young people aged under 25 years with a diagnosed eating disorder and the associated positive outcomes. In doing so, this review has highlighted the paucity of studies related to social support for young people with eating disorders. Despite only seven studies being identified, the findings show some promising preliminary evidence for the acceptability and feasibility of social support as an adjunct to formal treatment. Some improvements were reported across several socialisation domains: self-esteem (Lázaro et al., 2011; Scott Richards et al., 2006; Yager, 2001), social skills (Lázaro et al., 2011), self-concept (Lázaro et al., 2011; Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009), motivation to change (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Tierney, 2008; Yager, 2001), spiritual well-being (Scott Richards et al., 2006) and psychopathology (Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Scott Richards et al., 2006; Yager, 2001); however, a note of caution is necessary given the self-reported nature of the assessment tools, the variability in tools measuring similar outcomes, the methodological quality (particularly the low-quality RCT), and small sample sizes. Nonetheless, young people's perception of the positive impact of social support on their recovery journey remains, which echoes the findings of the existing literature related to adults with eating disorders (Leonidas & Dos Santos, 2014; Linville et al., 2012) and further strengthens the argument for integrating social support elements into treatment programs as a means of attaining longer-term positive care outcomes.

Overall, all the studies have shown that social support, whether individual (asynchronous) or group support, provided a humanistic approach where open dialogue was fostered by someone listening with understanding and empathy. Social support espoused validation of the person's identity, connection with others, and hope for recovery and had the potential to increase self-esteem and self-worth. Psychological well-being is a fundamental component of eating disorder recovery and is influenced significantly by positive and supportive interpersonal relationships (de Vos et al., 2017). Strong social support systems are the leading facilitator of treatment uptake by people with eating disorders (Daugelat et al., 2023) and, while family-based therapies remain the gold-standard approach for the younger eating-disordered population (Hay et al., 2014; Rienecke & Le Grange, 2022), the evidence-base on outcomes for multi-family therapy are mixed (Baudinet et al., 2021). Notwithstanding this, a consistent theme for parents and young people is the perception of support when surrounded by like-minded people with shared experiences (Baudinet et al., 2021), which was a sentiment expressed in three of the included studies (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Tierney, 2008).

While it is important for people with an eating disorder to be motivated to change (Fogarty & Ramjan, 2018) or as Dawson et al. (2014) describe to be at the “tipping point of change”, it was interesting that family (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009; Tierney, 2008), friends/peers (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009; Tierney, 2008) and more specifically mothers (Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009; Tierney, 2008), played an important role as providers of social support. Also, health care professionals (Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009; Yager, 2001) were important support providers although there were aspects of health care professionals which were more or less helpful. Considering the role mothers are playing in providing socio-emotional support to their children, greater attention should be invested in capacity building the whole family with the requisite skills in this respect as well as other non-professionals to distribute the load. A concerted effort should also be made in ensuring these individuals are prepared with their own support system if they are to undertake this role. This also accords with a review of social support networks for people with eating disorders (Linville et al., 2012) that emphasised the need to expand beyond family-centred relationships, and some encouraging progress has been made in recent years. For example, several studies have explored peer mentorship as an adjunct to traditional treatment programs and found the pairing of recovered mentors with recovering mentees to be an acceptable, feasible, and effective method for improving eating disorder psychopathology (Beveridge et al., 2019; Hanly et al., 2020; Ramjan et al., 2017, 2018; Ranzenhofer et al., 2020). However, Beveridge et al. (2019) found peer mentors experienced an increase in eating disorder symptomology alongside the improvements in mentees' outcomes and in Ramjan et al. (2017) where mentors had lower confidence levels regarding their ability to handle challenging situations. The duality of the relationship between young people with eating disorders—helping and being helped while also triggering and being triggered—was also reflected in this review (Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Tierney, 2008) and showed the importance of ensuring that interventions are conducted in a controlled and moderated environment which could also be in the form of online or email peer support (Kendal et al., 2017; Peebles et al., 2022).

It is not surprising that friendships and peers were also highly prized in the studies in this review as it is consistent with the literature (Beveridge et al., 2019; Hanly et al., 2020; McNicholas et al., 2018; Ramjan et al., 2017, 2018; Ranzenhofer et al., 2020) which shows an aspiration to engage with others at different stages of recovery while also acknowledging the well-established potential to normalise, validate, and inspire their own journeys (Lewis & Foye, 2022; Linville et al., 2012). It was interesting that young people continue to express the need for greater therapeutic support from nurses and other healthcare professionals (Tierney, 2008). With education and training, nurses and other healthcare professionals could play a more pivotal role in providing psychosocial support during treatment. Investment should ideally start at the undergraduate level with a greater understanding of eating disorders, person-centred care, and therapeutic communication.

Within treatment, the hyper-focus on weight and behaviours to the detriment of psychosocial recovery was evident (Tierney, 2008). Recent work by Zugai et al. (2023) also highlighted that “the conflict between clinicians' biomedical focus [on weight gain] and consumers' broader unmet needs leads to harmful interpersonal dynamics and feelings of invalidation”. Young people described limited interpersonal and life skills training that would potentially reduce social isolation and improve anxieties with re-integration post treatment (Tierney, 2008). This supports the work of Fogarty and Ramjan (2016) where psychosocial recovery was remiss during inpatient care: “when in inpatient treatment the focus was on physical restoration so when I was discharged at the ‘target weight’, I was still the same emotionally as when I was admitted”.

The type of support received across the seven studies (Lázaro et al., 2011; Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009; Scott Richards et al., 2006; Tierney, 2008; Yager, 2001) aligned closely with the model of social support proposed by Berrett and Cox with some overlap between domains and a strong focus on informational support (e.g., advice), feedback (e.g., validation), emotional support (e.g., encouragement, empathy), belonging (e.g., sense of identity), relief (e.g., distraction) and to a lesser extent instrumental support such as assistance (e.g., giving or receiving material goods, financial support) (Berrett, 2009). Perhaps the most clinically relevant findings from this review, although not new, were the importance of open dialogue, someone listening (Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016; Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Quiles Marcos & Terol Cantero, 2009; Tierney, 2008; Yager, 2001) and hearing from those at different stages (Monaghan & Doyle, 2023; Tierney, 2008) as intrinsically motivating factors for hope for recovery.

The presence of confounding factors, including comorbidities and neurodiversity in lived experience (Leppanen et al., 2022), and their potential impact on care outcomes should be considered in future research to better elucidate the efficacy of social supports (Lázaro et al., 2011; Malmendier-Muehlschlegel et al., 2016). Future longitudinal studies are warranted in social support and eating disorders to determine the longer-term treatment outcomes. Further the acceptability and feasibility of sustainable modalities of providing social support in eating disorders should be explored through a range of research methodologies, particularly high-quality RCTs.

Strengths and limitations

We acknowledge the difficulty in drawing conclusions within this integrative review on the benefits of social support and eating disorders because of the following: (1) the methodological quality of several studies, (2) exclusion of non-English language studies, (3) exclusion of grey literature and protocols and (4) exclusion of social supports that are a core component of formal treatment. A strength of the review method is the comprehensive and rigorous search process.

Relevance for clinical practice

Without early intervention, eating disorders can become more entrenched and chronic. Social support can be pivotal to the development of healthy relationships, improved mental health and a sense of identity among young people. Positive findings from this review support further consideration of early intervention programs that include social support as an adjunct to treatment. Further, there is a need to explore ways to enhance existing social support within therapeutic relationships with healthcare professionals, as nurses could play a more pivotal role in providing psychosocial support during treatment.

CONCLUSION

Despite the small number and heterogeneity of the studies, this review has highlighted some promising preliminary evidence for the benefits of social support for young people diagnosed with an eating disorder. Further research is warranted as to how future treatment for eating disorders should incorporate or embed adjunct modalities that capacity build and empower young people and enhance their psychosocial recovery.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Lucie M. Ramjan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original draft, Writing – Review & Editing. Brandon W. Smith: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original draft. Jane Miskovic-Wheatley: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – Review & Editing. Sheeja Perumbil Pathrose: Conceptualization, Validation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Review & Editing. Phillipa J. Hay: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – Review & Editing.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Melissa Burley (Specialist Librarian), School of Nursing and Midwifery, Western Sydney University for her support. Open access publishing facilitated by Western Sydney University, as part of the Wiley - Western Sydney University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Phillipa Hay receives/has received sessional fees and lecture fees from the Australian Medical Council, Therapeutic Guidelines publication and HETI (New South Wales and the former NSW Institute of Psychiatry) and royalties/honoraria from Hogrefe and Huber, McGraw Hill Education, and Blackwell Scientific Publications, Biomed Central and PlosMedicine and she has received research grants from the NHMRC and ARC. She is Chair of the National Eating Disorders Collaboration Steering Committee in Australia (2019) and was a Member of the ICD-11 Working Group for Eating Disorders, and was Chair Clinical Practice Guidelines Project Working Group (Eating Disorders) of RANZCP (2012–2015). She has prepared a report under contract for Takeda (formerly Shire) Pharmaceuticals in regards to Binge Eating Disorder (July 2017) and is a consultant to Takeda Pharmaceuticals. All views in this article are her own.

REGISTRATION

The review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42023422212).

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.