2025 Guidelines for direct oral anticoagulants: a practical guidance on the prescription, laboratory testing, peri-operative and bleeding management

Funding: None.

Conflict of interest: None.

Abstract

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are widely prescribed to prevent and treat venous and arterial thromboembolism, supported by published evidence, and are preferred over warfarin in many guidelines. Although the risk of major bleeding, in particular intracranial haemorrhage (ICH), is decreased with DOACs, gastrointestinal bleeding is increased with some DOACs, and the case fatality rate of bleeding remains high. Therefore, it is important to (i) prescribe DOACs appropriately, (ii) have strategies to manage major bleeding including the use of specific reversal agents and (iii) interrupt and resume DOACs for procedures. The main recommendations are as follows: (i) Select the appropriate dose of DOAC according to indications and consider patient factors to minimise bleeding risks; (ii) DOACs do not require routine laboratory testing; (iii) for life-threatening uncontrollable bleeding, specific agents can be used to reverse the anticoagulant effects of DOACs; and (iv) DOACs can be interrupted for planned procedures without the need for ‘bridging’ with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH). The anticoagulant effects of DOACs can be reversed with specific agents, such as andexanet for apixaban and rivaroxaban and idarucizumab for dabigatran. If not available, pro-haemostatic agents such as prothrombin complex concentrates or activated prothrombin complex concentrates can be considered. DOACs can be interrupted and resumed for procedures without the need for ‘bridging’ with LMWH.

Background

Oral factor Xa inhibitors (FXaI, apixaban and rivaroxaban) and oral thrombin inhibitors (dabigatran) target specific activated coagulation factors and are referred to as direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs).1 With a fixed dosing regimen, less drug and food interactions, and no need for routine laboratory monitoring when compared to warfarin, their use has become widespread. The current indications for the DOACs are for the primary and secondary prevention of venous and arterial thromboembolism (Table 1), but there are specific circumstances when they should be avoided (Box 1). Overall, their introduction has impacted positively on the quality of life of patients needing anticoagulants.2

| VTE prevention | VTE treatment‡ | Atrial fibrillation (AF) | Stable atherosclerotic vascular disease | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initiation | Maintenance | ||||

| Apixaban‡,§,¶ | 2.5 mg twice daily post hip and knee replacements | 10 mg twice daily for 7 days | 5 mg twice daily; consider 2.5 mg twice daily beyond 6 months | 5 mg twice daily/or 2.5 mg twice daily†† | |

| Rivaroxaban‡‡ | 10 mg daily post hip and knee replacements | 15 mg twice daily for 21 days | 20 mg daily; consider 10 mg daily beyond 6 months | 20 mg daily / 15 mg daily§§ | 2.5 mg twice daily (combined with aspirin)¶¶,a |

| Dabigatranbc | 110 mg 1–4 h post-surgery, then 220 mg once daily post hip and knee replacementsd | 150 mg twice daily or 110 mg twice dailye |

150 mg oral twice daily or 110 mg oral twice dailyf |

||

- † Approved indications: Therapeutics Goods Association of Australia (TGA) and/or Medsafe, New Zealand (NZ).

- ‡ Dabigatran is not reimbursed for VTE treatment by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, Australia; apixaban is not reimbursed by Pharmac, New Zealand.

- § Not funded for this indication in New Zealand.

- ¶ Use not recommended with CrCl < 25 mL/min.

- †† Apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily, two out of three (serum creatinine ≥ 133 mmol/L, age ≥ 80 years and weight ≤ 60 kg).

- ‡‡ Use not recommended with CrCl <15 mL/min.

- §§ Rivaroxaban 15 mg once daily in patients with moderate renal impairment (creatinine clearance 15–49 mL/min).

- ¶¶ Coronary artery disease with one additional risk factor; peripheral arterial disease with one additional risk factor.

- a Peripheral arterial disease after acute revascularisation (not PBS funded but efficacy and safety established in large phase RCT).

- b Not funded for VTE prevention or VTE treatment in Australia.

- c Use not recommended with CrCl < 30 mL/min.

- d Consider reducing the dose to 150 mg once daily for those with CrCl 30–50 mL/min or in those with increased risk of bleeding.

- e Dabigatran 110 mg twice daily for patients ≥80 years or with increased risk of major bleeding.

- f Dabigatran 110 mg twice daily, CrCl, 30–50 mL/min.

- VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Box 1. Scenarios where use of direct oral anticoagulants is not advised.

|

|

|

|

|

†Apixaban, dabigatran and rivaroxaban are not recommended with CrCl <25 mL/min, <30 mL/min and <15 mL/min respectively.

‡Apixaban is contraindicated in Child-Pugh C; rivaroxaban in Child-Pugh B and C; dabigatran with liver enzymes ×2 upper limit of normal.

§Lupus anticoagulant (non-specific inhibitor), anticardiolipin antibodies and anti-B2 glycoprotein antibodies.

The efficacy of DOACs has been established in multiple large, multicentre randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), chronic stable atherosclerotic disease and venous thromboembolism (VTE; including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE)) (GRADE 1A).3-5 Compared with warfarin, all DOACs achieved non-inferiority with regard to prevention of stroke, systemic embolism and recurrent VTE events. Dabigatran at a dose of 150 mg twice daily also demonstrated superiority over warfarin in stroke prevention in patients with AF.6 Preventive doses of apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily and rivaroxaban 10 mg once daily maintained efficacy in preventing recurrent VTE beyond 6 months, without a significant increase in bleeding compared to aspirin or placebo.7, 8

The clearance of DOACs relies primarily on renal function, though the extent varies between the different DOACs. A careful assessment of risk–benefit should be undertaken for use of DOACs in patients with CrCl <30 mL/min. In Australia and New Zealand, dose adjustment of dabigatran is recommended with CrCl ≤50 mL/min, with contraindication of use if CrCl ≤30 mL/min. Apixaban and rivaroxaban use is not recommended for CrCl <25 mL/min and CrCl <15 mL/min respectively. DOACs should also be used cautiously in patients with liver dysfunction (Box 1). DOACs are contraindicated in Childs-Pugh class C cirrhosis (apixaban but not rivaroxaban may be used in class B). There is a paucity of data regarding the use of DOACs at the extremes of body weight (body mass index > 40 kg/m2). Hence, the use of DOACs remains challenging in patients with significant renal or liver impairment, in low-body-weight and morbidly obese patients.

DOACs have less drug–drug interactions, but significant interactions can occur with medications which interact with P-glycoprotein and/or CYP3A4. Combining antiplatelet drugs and certain other medicines with DOACs increases the risk of bleeding. Utilising online specific drug interaction checkers is highly recommended (https://amhonline.amh.net.au/).9

An important safety advantage reflected in all of the RCTs involving DOACs, and confirmed by meta-analyses, is the significant reduction in intracranial haemorrhage (ICH) compared to warfarin.3, 5, 10 DOACs have also been associated with less major bleeding, less clinically relevant non-major bleeding (CRNMB) and less fatal bleeding in patients with VTE.5 In the VTE population, the rates of major bleeding and CRNMB per year with DOACs have been 1.1% and 6.3% respectively, compared to 1.8% and 8.0% with warfarin.

Compared to warfarin, the estimates of major bleeding are lower with DOACs overall (1%–4% per year).3, 5 However, when major bleeding occurs, there is an associated case fatality rate of 6%–8%, and even higher with ICH (up to 48%).10, 11 Consequently, there remains a significant need for safe and effective management of major bleeding episodes when they occur.

Finally, up to 10% of patients receiving long-term anticoagulants require urgent or time-critical procedures each year.12 Some can be managed by withholding anticoagulation for a finite period, but in an emergency, an effective reversal strategy to avoid or minimise bleeding is needed.

- DOAC prescription

- Laboratory measurements of DOACs in appropriate scenarios

- Strategies to manage bleeding including the use of reversal agents and interruption of DOACs during perioperative periods.

Methods

Eight experts in thromboembolic diseases of the THANZ conducted three virtual and one face-to-face meeting (2 and 30 September 2022; 3 November 2023; and 17 July 2024) together with recurring emails, during which specific questions and drafts and revisions of the guidelines were discussed (refer to Appendix S1 for description of development process). The guidelines followed methods outlined by the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II instrument.13 Recommendations have been graded as strong or weak, rated according to quality of the levels of available evidence (GRADE) (Table 2).14 The views of DOAC users were not sought.

| Recommendation | GRADE† | |

|---|---|---|

| Strength | Quality | |

| DOACs are indicated for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), chronic stable atherosclerotic disease, the treatment of new deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, and secondary prevention of VTE, as well as the prevention of venous thrombosis in hip and knee arthroplasty. | 1 | A |

| DOACs do not routinely require laboratory monitoring. | 1 | A |

| Idarucizumab can be administered to patients with uncontrolled bleeding related to dabigatran or prior to an urgent procedure as it rapidly and safely reverses the anticoagulant effect and achieves adequate haemostasis. | 1 | B |

| Andexanet can be administered to patients with life-threatening and uncontrolled bleeding related to apixaban and rivaroxaban as it effectively reduces the anticoagulant effects and achieves adequate haemostasis | 2 | B |

| Four-factor prothrombin complex concentrates (4F-PCC) and activated prothrombin complex concentrates (FEIBA) can improve haemostasis in patients with life-threatening and uncontrolled bleeding related to apixaban and rivaroxaban. | 2 | C |

| Activated charcoal should be considered in patients with moderate/severe bleeding who present within 2 h of the last dose of DOAC. | 2 | C |

| Tranexamic acid can be prescribed as an adjunct in DOAC-related major bleeds. | 2 | C |

| Anticoagulation can be resumed 1–6 weeks after major bleeding, depending on individual bleeding and thrombosis risk. | 2 | C |

| DOAC-specific reversal agents and haemostatic agents are unlikely to improve outcome in patients taking dabigatran with a drug level of <50 ng/m, or in patients on rivaroxaban or apixaban with drug level <75 ng/mL. | 2 | C |

Apixaban and rivaroxaban can be interrupted 1–2 days before procedures depending on renal function with a low rate of peri-procedure thrombosis and bleeding. |

1 | B |

| Dabigatran can be interrupted 2–4 days before procedures depending on renal function with a low rate of peri-procedure thrombosis and bleeding. | 1 | B |

| Perioperative bridging with heparin is not indicated because of the short half-lives and rapid onset of action of the DOACs. | 1 | B |

| FXa inhibitors can be safely interrupted 72 h prior to neuraxial anaesthesia in patients with adequate renal function. | 1 | B |

| Dabigatran should be interrupted 96 h prior to neuraxial anaesthesia in patients with CrCl 30–50 mL/min. | 1 | B |

| Therapeutic dose anticoagulation with DOACs can be resumed 48--72 h after a procedure (provided there are no ongoing bleeding risks). | 1 | B |

- † Grading system employed to append recommendations13, 15: Strength of recommendation: 1 – Strong; 2 – Weak. Levels of Evidence: A – High-quality systematic reviews or RCTs; B – SR or individual cohort studies; C – Well-designed phase 2 studies or good-quality case series; D – Expert panel consensus. Strength of recommendation and grading of evidence as reviewed by the expert panel. Statements graded 1A are strong consensus recommendations supported by high-quality meta-analyses, while statements graded 2C are weak recommendations supported by phase 2 studies or case series. The strength of recommendation rating reflects the extent to which the panel is confident that the desirable effects (i.e. benefits, such as improved outcome) of a recommendation considerably outweigh the undesirable effects (i.e. harms, such as adverse events) based on the available evidence.

- GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation.

Recommendations

See Table 2.

Prescription of DOACs

In both Australia and New Zealand, apixaban, rivaroxaban and dabigatran are indicated for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with AF, chronic stable atherosclerotic disease, the treatment of new DVT and PE, and secondary prevention of VTE, as well as the prevention of venous thrombosis in hip and knee arthroplasty. Table 1 summarises the dosing and indication for each DOAC.

DOACs and laboratory testing

DOACs do not routinely require laboratory monitoring because of predictable pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics (GRADE 1A). Unlike warfarin, DOACs have peaks and troughs because of a relatively short half-life, producing a peak anticoagulant effect at 2–3 h after intake. Therefore, any DOAC laboratory measurements must be interpreted in the context of the DOAC prescribed, known dosage and time of last administration. Clinical circumstances under which measurement of anticoagulant effect may impact management are in Box 2.16, 17

Box 2. Circumstances where measuring direct oral anticoagulants-specific anticoagulant effect may be warranted

| Major bleeding |

|

|

|

|

|

|

An activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) or prothrombin time (PT) within the normal range does not exclude elevated DOAC levels (up to 100–150 ng/mL) that may contribute to ongoing bleeding or impairment of haemostasis with surgery.18, 19 The sensitivity of each laboratory's aPTT and PT to increasing DOAC concentration is wide-ranging and depends on the instrument and reagent. There is no international DOAC coagulation method to standardise results such as the international normalised ratio (INR) for warfarin. With knowledge of this limitation, some clinicians may still consider reviewing the aPTT for dabigatran and PT for rivaroxaban in emergencies; the PT is generally insensitive to apixaban. Conversely, even small concentrations of dabigatran prolong the thrombin time (TT), such that a normal result excludes the presence of dabigatran but should not be used to estimate dabigatran concentration or for correction before surgery.20, 21

Quantification of plasma DOAC drug levels determined by specific coagulation assays (dilute TT, ecarin clotting time for dabigatran and calibrated anti-FXa chromogenic assays for apixaban and rivaroxaban) are well validated for precision and monitored by external quality assurance programmes.21-23 However, the awareness of clinicians of the need to obtain a rapid DOAC level, as with an INR result for warfarin in an emergency, is lacking. Approximately one in five patients taking DOACs who present with bleeding or require urgent surgery have no detectable DOAC present.18, 19, 24 In contrast, a timely result would significantly impact decisions regarding specific DOAC haemostatic reversal agents or blood products. In this context, it falls to individual organisations to develop workflows which afford a prompt turnaround time of relevant coagulation testing, which would likely improve patient safety, clinical outcomes and cost effectiveness of DOAC reversal.

Reversal agents

Idarucizumab

Idarucizumab, a monoclonal antibody fragment that binds directly to dabigatran, has been shown to reverse rapidly and safely its anticoagulant effect in patients with uncontrolled bleeding or prior to an urgent procedure.25, 26 It can also be considered in other clinical situations, for example, prior to thrombolysis in patients with acute coronary syndrome or ischaemic stroke. In patients with adequate renal function, idarucizumab is unlikely to provide a clinically significant benefit if the last dose of drug was more than 24 h prior. There are no reliable cut-off values to decide whether surgery or invasive procedures can be carried out. Still, it is generally agreed that it is safe to proceed (without using idarucizumab) if the dabigatran level is <50 ng/mL or <30 ng/mL where any excess bleeding is unacceptable, such as neurosurgery.27 In patients with high dabigatran levels, particularly with renal impairment, further doses of idarucizumab may be required to avoid the reappearance of dabigatran in the circulation 12–24 h after the last dose.28

Andexanet-alfa

Andexanet-alfa is a recombinant inactive form of human factor Xa developed for reversal of factor Xa inhibitors, with a cohort study showing that 82% of patients with acute major bleeding had excellent or good haemostatic efficacy and a greater 90% reduction in the anti-FXa level from baseline; patients requiring urgent surgery were not assessed.29 The thrombotic event rate was 10% in this cohort at day 30, but no events occurred after the resumption of anticoagulants among patients who did restart. Andexanet use in FXaI-related acute ICH was associated with an increased rate of ischaemic stroke, but not other thrombotic events compared with standard of care.30 Therefore, the use of andexanet should be carefully considered, weighing up the benefits and risks for adult patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban where reversal is required due to life-threatening or uncontrolled bleeding, and where the last known dose of apixaban or rivaroxaban was <18 h prior. If the timing of the last dose is unknown, an urgent drug-specific anti-FXa level should be obtained and andexanet given if the level is >75 ng/mL.29 The use of andexanet is not indicated in those having planned surgery without current major bleeding, for those expected to receive heparin or other haemostatic agents within 12 h of andexanet treatment, those who have received PCC or rFVIIa products within the last 7 days and those with a recent history of thrombosis (<2 weeks). There is currently no evidence supporting the use of andexanet prior to thrombolysis among patients taking a FXaI who present with an ischaemic stroke or other indications for thrombolysis. As the pharmacodynamic half-life of andexanet is relatively short, approximately 4 h, reappearance of plasma rivaroxaban and apixaban was observed after cessation of the 2-h infusion. Subsequent monitoring of anti-FXa levels may be useful, particularly in those with renal impairment or who are still bleeding; however, anti-FXa measurements after andexanet administration are not accurate due to its interference with currently available assays.28 The andexanet dosing (low vs. high) depends on the XaI, dose and timing of the last dose (Fig. 1), as per the product datasheet.30

Tranexamic acid

Tranexamic acid (TXA) reduces bleeding by reducing clot breakdown (fibrinolysis) and is used in most algorithms for moderate to major bleeding, particularly for bleeding at sites with high fibrinolytic activity such as the GI tract. TXA has been shown to reduce bleeding in the setting of trauma (CRASH trials) and post-partum haemorrhage (WOMAN trial) but did not reduce death from GI bleeding in the HALT-IT trial.31-33 The HALT-IT trial also showed increased rates of VTE events and seizures, and as there are no data to demonstrate improved outcomes or otherwise in DOAC-related bleeding, no firm recommendations can be made.

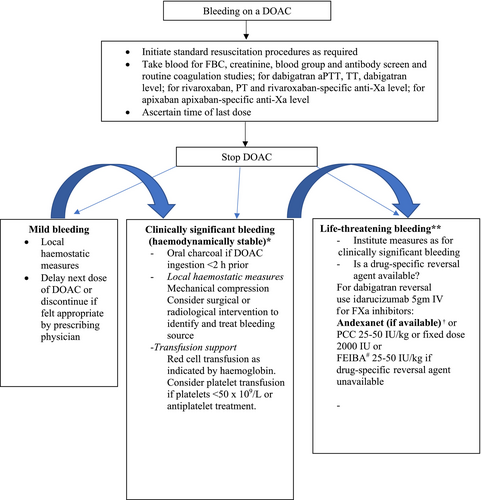

Managing DOAC-related bleeding

General principles in management of patients with bleeding while receiving DOACs

- Drug discontinuation: The anticoagulant should be ceased at least temporarily in all patients presenting with significant bleeding. The timing of recommencement will depend on the severity of bleeding, the presence of ongoing risk factors for bleeding, the risk of thrombosis and the initial indication for anticoagulant therapy.

- Baseline laboratory assessment: The time of the last DOAC ingestion should be established (if known). Baseline assessment of haemoglobin should be performed to assess bleeding severity. Standard coagulation tests (aPTT, TT and PT) and, where available, anticoagulant-specific drug level assessments should be performed to assess the contribution of the drug to the bleeding event and to guide the need for intervention. Creatinine should also be measured to assess renal function and allow prediction of expected rate of anticoagulant drug clearance.

- General supportive care measures: Patients with minor bleeding should be managed with local measures (e.g. mechanical compression). Surgical and radiological procedures to identify the bleeding source and to limit ongoing bleeding should be performed as appropriate, considering the risk of procedure-related bleeding in an anticoagulated patient. Red cell transfusion should be administered as clinically appropriate. Platelet transfusion should be considered in patients on concurrent anti-platelet therapy or with significant thrombocytopenia (platelets <50 × 109/L).

- Activated charcoal: Administration of activated charcoal should be considered in patients with moderate/severe bleeding who present within 2 h of the last dose of DOAC, although there is potential for efficacy up to 8 h after DOAC administration34 (GRADE 2C).

- Administration of haemostatic agents: Where available, a drug-specific reversal agent can be given for major, life-threatening bleeding. In its absence, an alternative haemostatic agent may need to be considered. Four-factor prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs) at a dose of 25–50 U/kg have been shown to be moderately effective in the treatment of patients on factor Xa inhibitors presenting with major bleeding (69.1%) with a low thromboembolic event rate (2.3%)35, 36 (GRADE 2C). Alternatively, a fixed dose of 2000 IU can be used, with a recent meta-analysis of 25 studies showing no difference in the reduction in bleeding, thromboembolic rates or mortality when comparing weight-based with fixed dosing.37 Activated prothrombin complex concentrate (FEIBA) has been shown to be effective at obtaining haemostasis in DOAC-related bleeding events at 25–50 U/kg doses38 (GRADE 2C). Use of rFVIIa is not recommended, based on less consistent data on its ability to reverse anticoagulant effect derived from animal and laboratory models and its association with the risk of thrombosis when used outside patients with haemophilia.39

- Of all the DOACs, only dabigatran is removed by haemodialysis, but it is rarely performed because of the availability of idarucizumab. DOAC-specific reversal agents and haemostatic agents are unlikely to improve outcome in patients taking dabigatran with a drug level of <50 ng/mL or in patients on rivaroxaban or apixaban with drug level <75 ng/mL (GRADE 2C).29 Tranexamic acid should also be considered.

Figure 1 shows the algorithm to manage DOAC-related bleeding.

Resumption of AC after major bleeding

Following the cessation of bleeding, treatment of identifiable underlying causes, the need for anticoagulation and its benefit should be reviewed, including the choice and dose of anticoagulant. This needs to be weighed against the risk of recurrent bleeding, and risk factors for bleeding should be addressed and modified if feasible. For most patients, resumption of anticoagulation is favoured unless the recurrent bleeding risk is high and cannot be reduced to an acceptable level with treatments or interventions targeted at addressing the underlying cause of bleeding. The optimal timing for anticoagulant resumption based on current available evidence is between 1 and 6 weeks depending on individual bleeding and thromboembolism risk40 (GRADE 2C).

Perioperative management of patients receiving a DOAC undergoing elective surgery

Optimal management of the interruption of DOAC therapy for procedures remains an area of ongoing research. A meta-analysis of eight studies of perioperative DOAC interruption reported a thromboembolic risk of 0.41% and a major bleeding rate of 1.8%.41

The Perioperative Anticoagulation for Use in Surgery Evaluation (PAUSE) study was a pragmatic multicentre prospective management study of periprocedural management involving 3007 patients with AF taking apixaban, rivaroxaban or dabigatran, where a standard protocol of interruption and resumption was followed depending on the type of procedure (low or high bleeding risk) and renal function, designed to minimise the window with no anticoagulation and simplify protocols for ease of adherence.42 The overall 30-day rate of arterial thromboembolism and major bleeding was 0.16%–0.6% and 0.9%–1.85% for different DOACs respectively.43

Practical summary for perioperative interruption of DOAC42, 44

- Omit for 2 days before and the day of surgery for surgeries with a high risk of bleeding.

- Omit for 1 day before and the day of surgery for surgeries with low to moderate risk of bleeding (GRADE 1B).

- Omit 1 day before and the day of surgery (GRADE 1B).

-

For surgery with high bleeding risk

- Omit for 4 days and the day of surgery if CrCl is <50 mL/min

- Omit for 2 days and the day of surgery if CrCl is ≥50 mL/min (GRADE 1B)

-

For surgery with low to moderate bleeding risk

- Omit for 2 days and the day of surgery if CrCl is <50 mL/min

- Omit for 1 day and the day of surgery if CrCl is ≥50 mL/min (GRADE 1B)

Perioperative bridging with heparin is not indicated because of the short half-lives and rapid onset-offset of action of the DOACs

The measurement of FXaI-specific anti-Xa levels prior to surgery is generally not necessary except in patients with chronic kidney disease (for FXaI, stage 4, CrCl 15–29 mL/min or less; for dabigatran Stage 3a, CrCl ≤45–59 mL/min (GRADE 1B)).

Surgery involving neuraxial anaesthesia in patients receiving DOACs

International guidelines and data from management studies recommend a 72-h interruption of FXaI prior to surgery or until the direct FXa drug level is <30 ng/mL42, 43, 45 (GRADE 1B). For dabigatran, 72 h was recommended in correlation with anticoagulant drug levels with renal impairment by European guidelines.45 However, it is reasonable to follow the PAUSE recommended interval of 96 h for patients taking dabigatran with a CrCl of 30–50 mL/min, but levels should be considered in elderly patients, particularly if renal function is close to 30 mL/min, ensuring a drug level of <30 ng/mL43 (GRADE 1B).

Resumption of DOAC after surgery

- Therapeutic doses of apixaban, rivaroxaban and dabigatran can be resumed 48–72 h after surgery with high bleeding risk (GRADE 1B). For patients at continued high risk for bleeding, a prophylactic dose of anticoagulant (e.g. apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily or rivaroxaban 10 mg daily, orally, or enoxaparin 40 mg subcutaneously daily) can continue until it is safe to resume therapeutic dosing.

- If patients are usually on the prophylactic dose of FXaI (e.g. apixaban 2.5 mg bd or rivaroxaban 10 mg daily), these can be resumed 12–24 h after surgery in the absence of increased bleeding risk.

- LMWH as thromboprophylaxis can be used in patients with unpredictable oral drug absorption.

Conclusion

This is the first evidence-based update on the management of patients receiving DOACs in a decade in Australia and New Zealand. We encourage following the recommendations to standardise practice. More evidence is needed to establish whether andexanet is associated with a net clinical outcome benefit in life-threatening bleeds, given the increased rate of thrombosis associated with its use.

Acknowledgements

The co-authors' contribution to this guideline is unfunded. Open access publishing facilitated by Monash University, as part of the Wiley - Monash University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.