Clinical guidelines for male lower urinary tract symptoms and benign prostatic hyperplasia

Abstract

The present article is the abbreviated English translation of the Japanese guidelines for male lower urinary tract symptoms and benign prostatic hyperplasia updated as of the end of 2016. The target patients are men aged >50 years complaining of lower urinary tract symptoms, with or without benign prostatic hyperplasia, and the target readers are non-urological general physicians and urologists. Mandatory assessment for general physicians is medical history, physical examination, urinalysis and measurement of serum prostate-specific antigen. Additional mandatory assessment for urologists is symptoms and quality of life assessment by questionnaires, uroflowmetry, residual urine measurement, and prostate ultrasonography. Nocturia requires special attention, as it can result from nocturnal polyuria and/or sleep disturbance rather than lower urinary tract disorders. Functional lower urinary tract disorders with or without benign prostatic hyperplasia are primarily managed by conservative therapy and medications, such as α1-blockers and phosphodiesterase-type 5 inhibitors. Use of other medications or combination pharmacotherapy is to be reserved for urologists. 5α-Reductase inhibitors and anticholinergics or β3 agonists are indicated for men with enlarged prostates and overactive bladder symptoms, respectively. Surgical intervention for bladder outlet obstruction is considered for persistent symptoms or benign prostatic hyperplasia-related comorbidities. Surgical modalities should be optimized by the patient's characteristics, performance of equipment and the surgeon's experience.

Abbreviations & Acronyms

-

- BOO

-

- bladder outlet obstruction

-

- BPH

-

- benign prostatic hyperplasia

-

- ICS

-

- International Continence Society

-

- IPSS

-

- International Prostate Symptom Score

-

- JUA

-

- Japanese Urological Association

-

- LUTS

-

- lower urinary tract symptoms

-

- OAB

-

- overactive bladder

-

- PDE5i

-

- phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor

-

- PSA

-

- prostate-specific antigen

-

- PVR

-

- post-void residual

-

- Q max

-

- maximum urinary flow rate

-

- QOL

-

- quality of life

-

- RCT

-

- randomized controlled trial

-

- TURP

-

- transurethral resection of the prostate

1 Introduction

Japanese clinical guidelines for male LUTS1 and those for BPH2 were published in 2009 and 2011, respectively. These guidelines have been combined and updated based on the evidence available as of the end of year 2016. The target subjects are men aged >50 years complaining of LUTS, with or without BPH, and the target readers are urologists and non-urologist general physicians. This article is the abbreviated English translation of the most updated Japanese guidelines for male LUTS and BPH.

2 Method

The Guidelines were developed by committee members recommended by the JUA and the Japanese Society of Internal Medicine. The members reviewed relevant references retrieved from the PubMed and Japana Centra Revuo Medicina databases released between 2010 and 2016. Other information sources included previous guidelines,1, 2 the BPH guidelines published by the American Urological Association3 and the European Association of Urology.4 A draft was peer-reviewed by JUA executive members and was open to public opinion before finalizing. Funding was provided by the JUA. Conflict of interest is regulated according to JUA bylaws.

3 Clinical algorithm

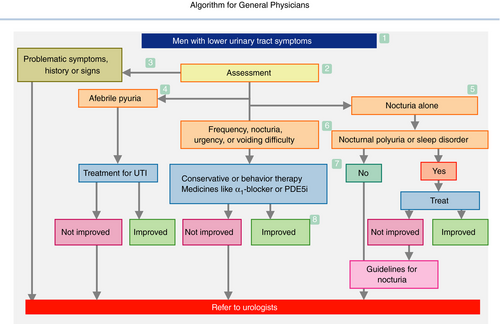

3.1 Algorithm for general physicians (Fig. 1)

- The algorithm is applicable to men aged ≥50 years with male LUTS. The possible disorders include BPH, prostatitis, prostatic cancer, OAB, underactive bladder, bacterial cystitis, interstitial cystitis, bladder cancer, bladder stones, urethritis, urethral stricture, neuropathic diseases, polyuria and nocturnal polyuria.

- The basic assessment comprises of present history, past history, physical examination, urinalysis and determination of serum PSA level. Optional assessments, selected on an individual basis, include symptom and QOL questionnaires, bladder diary, PVR measurement, urine culture, urine cytology, serum creatinine levels and prostate ultrasonography.

- Referral to urologists is advised, when the assessments show “problematic” abnormalities, such as severe symptoms, and bladder or urethral pain; history of urinary retention, recurrent urinary tract infection, gross hematuria, pelvic surgery or radiotherapy and neurological disorders; bladder distention, a highly enlarged or painful prostate and prostate nodule; hematuria, febrile pyuria, elevated PSA, positive urinary cytology, PVR ≥100 mL, bladder stones, abnormality on imaging tests and renal insufficiency.

- Afebrile pyuria should be treated by antibiotics, and referred to urologists when it persists or recurs.

- Monosymptomatic nocturia can be caused by nocturnal polyuria and/or sleep disturbance. Overhydration, cardiac or renal insufficiency, hypertension, diabetes and sleep apnea syndrome are possible disorders. Voiding diary recording is recommended to diagnose them.

- The most probable conditions here are BPH and/or bladder dysfunction. Confirm the patient's desire or medical need for treatment. On starting treatment, PVR measurement is recommended.

- Conservative or behavior therapy and/or medical therapy using medicines, such as α1-blocker or PDE5i, should be indicated. Remaining OAB symptoms might be improved by anticholinergics or β3 agonists; however, referral to urologists is recommended.

- Monitor symptoms periodically, and consider cessation or reduction of medicines.

3.2 Algorithm for urologists (Fig. 2)

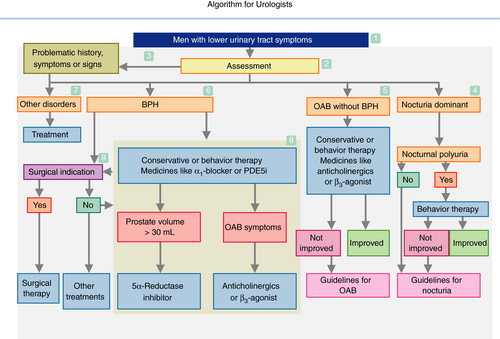

- The algorithm is applicable to men aged ≥50 years with LUTS. The readers should consult Figure 1 first.

- The basic assessment comprises of present history, past history, symptom and QOL questionnaires, physical examination, urinalysis, serum PSA level, uroflowmetry, PVR measurement, and prostate ultrasonography. Optional assessments include bladder diary, urine culture, urine cytology, advanced urodynamic studies, endoscopy, radiological examinations, serum creatinine levels and imaging tests for the upper urinary tract.

- Consider other disorders, when the assessments reveal “problematic” abnormalities, such as severe symptoms, and bladder or urethral pain; history of urinary retention, recurrent urinary tract infection, gross hematuria, pelvic surgery or radiotherapy and neurological disorders; bladder distention, a highly enlarged or painful prostate and prostate nodule; hematuria, febrile pyuria, elevated PSA, positive urinary cytology, PVR ≥100 mL, bladder stones, abnormality on imaging tests and renal insufficiency.

- When nocturia is the dominant symptom, voiding diary recording is recommended. Nocturnal polyuria, if present, should be managed by behavior therapy. Refer to clinical guidelines for persistent nocturia or nocturia without nocturnal polyuria.

- Confirm the patient's desire or medical need for treatment of OAB symptoms without BPH. The symptoms are to be managed by conservative or behavior therapy and/or medical therapy with anticholinergic or β3 agonist. On starting treatment, PVR measurement is recommended. Refer to clinical guidelines for persistent OAB symptoms.

- Confirm the patient's desire or medical need for treatment of BPH. BPH should be treated with conservative therapy or behavior therapy and/or medical therapy with α1-blocker or PDE5i. Surgical indication might be considered.

- Consider detrusor underactivity as one of the other disorders.

- When the prostate is enlarged (≥30 mL), (co-)administration of 5α-reductase inhibitors is indicated. Anticholinergics and β3 agonists are indicated for persisting OAB symptoms.

- Surgery is indicated for uncontrollable symptoms as a result of BOO and/or BPH-related complications. Pre-surgical tests should include a pressure-flow study or its substitutes including intravesical prostatic protrusion.

4 Clinical questions

CQ 1: What medications or lifestyles worsen male LUTS?

A number of medicines, especially those with anticholinergic property, are known to aggravate LUTS (level 4).1 Obesity, hypertension, hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia are associated with LUTS.5, 6

CQ 2: What considerations should be made when assessing serum PSA values?

Serum PSA value is a tumor marker of prostate cancer, but increased in men with enlarged adenoma, urinary retention and prostatitis. It is reduced to approximately 50% by long-term use of anti-androgens or 5α-reductase inhibitors.1, 2

CQ 3: When is bladder diary recording recommended for assessment of male LUTS?

A bladder diary provides useful information for the etiology of urinary frequency. It is recommended for men with LUTS, especially with overactive bladder symptoms and nocturia in particular (grade B).1, 2, 4

CQ 4: What managements are recommended for urinary retention?

At first indwelling catheter or intermittent catheterization is indicated, followed by assessment of the upper urinary tract and reasons for retention (level 5; grade A).7, 8 Catheter removal is anticipated by administration of α1-blockers and/or 5α-reductase inhibitors for BPH (level 1; grade B).9 Surgical intervention is likely to be required for large prostates.10

CQ 5: What managements are initially recommended for nocturia?

Bladder diary recording is recommended to differentiate 1-day polyuria, nocturnal polyuria, bladder storage dysfunction and sleep disturbance. Treatment should be individualized according to each etiology (grade B).11-13

CQ 6: What conservative treatments are recommended for male LUTS?

Weight reduction is recommended for severe obesity (level 1; grade A).14, 15 Integrated behavioral therapy is recommended for LUTS, storage symptoms in particular (level 2; grade B).16, 17 Exercise, balanced diet and smoking cessation are also recommended (level 4; grade C1).1 Pelvic floor exercise and bladder training are recommended for OAB symptoms persisting after use of α1-blockers (level 2; grade B).18

CQ 7: Is there a type-dependent difference of α1-blockers in the efficacy and safety for BPH?

Efficacy appears to be equivalent among α1 subtypes (level 2),19, 20 although storage symptoms might be different.21 Adverse events, such as dizziness, hypotension, ejaculation dysfunction and intraoperative floppy iris syndrome, are variable among the types (level 2).22-26

CQ 8: Is there a difference between α1-blockers and PDE5i in the efficacy for BPH?

The efficacy of α1-blockers (as far as tamsulosin is concerned) and PDE5i for BPH is almost equivalent (level 2; grade B).27-29 PDE5i has efficacy for erectile dysfunction (ED); however, it is indicated differently in terms of dose and usage.

CQ 9: Is combined therapy of α1-blockers and PDE5i recommended for BPH?

Combined therapy of α1-blockers and PDE5i improves IPSS and Qmax better than monotherapy (level 2; grade C1). A concern is the increased risk of a cardiovascular event, such as orthostatic hypotension. Hypotension is more likely to occur with non-selective α1-blockers (i.e. doxazocin) than prostate-selective α1-blockers (i.e. tamsulosin and silodosin).28, 30-33

CQ 10: Is alternative medicine (i.e. health food and supplements) recommended for male LUTS?

Evidence supports the efficacy of some alternative medicines; however, it is not recommended because of inconsistency in results of efficacy, uncertainty in optimum dosage and concern about unclarified adverse events (level 1–2; grade C2).34-40

CQ 11: Is combined therapy of α1-blockers and anticholinergics or β3-agonists recommended for BPH-associated OAB symptoms?

Combined therapy of α1-blockers and anticholinergics is recommended for OAB symptoms associated with BPH (level 1; grade A).41-47 Combined therapy of α1-blockers and β3-agonists might be beneficial (level 3; grade C1).48, 49 In any case, anticholinergics or β3-agonists should be started carefully at low doses under monitoring voiding difficulty or urinary retention, especially for men with severe voiding symptoms, an enlarged prostate or advanced age. It is advisable to start α1-blockers first followed by the addition of anticholinergics or β3-agonists for persistent OAB symptoms.

CQ 12: Is combined therapy of α1-blockers and 5α-reductase inhibitors recommended for BPH?

Combined therapy of α1-blockers and 5α-reductase inhibitors is recommended for BPH with prostate volume >30 mL (level 1; grade A).50-53 Superiority of combined therapy to monotherapy of 5α-reductase inhibitors might be uncertain for BPH with prostates >60 mL.54

CQ 13: Is switching to monotherapy recommended after continuous combined therapy of α1-blockers and 5α-reductase inhibitors for BPH?

Most cases can switch to monotherapy of 5α-reductase inhibitors without symptom aggravation after combined therapy of α1-blockers and 5α-reductase inhibitors for 6 months to 1 year (level 2; grade C1).55, 56 Switching to monotherapy of α1-blockers might result in prostate regrowth and/or symptomatic worsening (level 4; grade C1).57 The outcomes of switching to monotherapy after combined therapy for longer than 1 year are unknown.

CQ 14: Is combined therapy of PDE5i and 5α-reductase inhibitors recommended for BPH?

Combined therapy of PDE5i and 5α-reductase inhibitors induces rapid improvement of LUTS with erectile function (level 2).58, 59 Long-term outcomes of combined therapy are uncertain, and the combination of dutasteride and tadalafil (both approved in Japan) has not been examined (reserved).

CQ 15: What treatments are recommended to avoid sexual dysfunction as an adverse event?

PDE5i are recommended to avoid ED. Surgical therapies other than holmium laser enucleation of the prostate and photoselective vaporization of the prostate might result in ED. Surgeries, α1-blockers, 5α-reductase inhibitors and anti-androgens should be avoided to prevent ejaculatory dysfunction. To retain libido, 5α-reductase inhibitors and especially anti-androgens should be avoided (level 1–2; grade A).24, 60-63

CQ 16: What should be attended to when physicians see men with BPH?

Some medicines, especially those with anticholinergic property, can exaggerate LUTS. Urethral catheter should be cautiously placed in men who experienced prostatic surgery to avoid urethral injury. Urinary retention after catheter removal should be managed by α1-blockers or intermittent catheterization (see CQ 4). Patients should be asked if they are taking α1-blockers and PDE5i, as α1-blockers can cause hypotension or intraoperative floppy iris syndrome, and combined use of PDE5i with nitrate or nitric oxide donors is contraindicated.64-66

CQ 17: When should urological consultation be considered for men with LUTS?

Consultation should be considered when: (i) history, symptoms or signs designated as “problematic” in the algorithm for general physicians are found; (ii) urinary tract infection recurs or persists despite appropriate medical therapy; and (iii) LUTS including nocturia are not successfully improved by behavioral therapy and/or medical therapy including α1-blockers and PDE5i (grade B).

CQ 18: When should the referral from urologists to general physicians be considered for men with LUTS?

The referral should be considered when appropriate management is undertaken for symptoms, history and signs that are potentially problematic to general physicians, and when stable management is anticipated by treatments or surveillance recommended for general physicians. Specific warning regarding the medicine or conditions for the patient should be attached.

5 Definition of male LUTS and BPH

5.1 Definition of LUTS

Classification and description of LUTS should be based on the ICS terminology standardization report.67 LUTS is divided into storage symptoms (i.e. frequency, urgency, incontinence), voiding symptoms (i.e. voiding difficulty, hesitancy), post-micturition symptoms (i.e. feeling of incomplete emptying) and others (i.e. bladder pain, syndromes). Common symptoms in men are nocturia, daytime frequency, voiding difficulty, feeling of incomplete emptying and urgency. Nocturia is the LUTS that most often impairs QOL. Assessment of LUTS is critical for diagnosis and outcome assessment, although LUTS is unreliable for predicting organ dysfunctions. Nocturia is unique; it is most common, often associated with non-urological conditions, such as nocturnal polyuria and sleep disturbance, and less related to other LUTS.1

Important terminology not defined in the ICS report includes underactive bladder, urinary retention, overflow incontinence and hypersensitive bladder. Underactive bladder is proposed as a symptom complex suggestive of detrusor underactivity, and is usually characterized by prolonged urination time with or without a sensation of incomplete bladder emptying, usually with hesitancy, reduced sensation on filling and a slow stream.68 Urinary retention signifies a condition in which the patient is unable to pass urine despite a large amount of urine accumulated in the bladder. Such patients might be incontinent, as intravesical pressure exceeds the urethral closure pressure, leading to urinary leakage (overflow incontinence). These terms are not recommended by the ICS report; however, urinary incontinence associated with chronic urinary retention must not be overlooked. Hypersensitive bladder is listed as a cause of bladder pain by the recent ICS terminology report.69 It refers to a bladder condition suggestive of sensory hyperactivity presenting with hypersensitive bladder symptoms (discomfort, pressure or pain in the bladder usually associated with urinary frequency and nocturia), but no proven bladder pathology or other explainable diseases.70

5.2 Definition of BPH

There is no uniform definition for BPH. The ICS report proposed the use of “BPH” exclusively as a histopathological term to refer to non-malignant hyperplasia of prostatic tissue, and coined a term “benign prostatic enlargement” (BPE) for an enlarged prostate and “benign prostatic obstruction” (BPO) for BOO. From a clinical and practical point of view, the current Guidelines keep BPH as a disease name, and have defined BPH as a disease with lower urinary tract dysfunction due to benign hyperplasia of the prostate, which is usually associated with enlargement of the prostate and lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of bladder outlet obstruction.2

6 Epidemiology and natural history of LUTS and BPH

LUTS associated with or without BPH is common in men. It can wax and wane, but generally progresses with aging.71 A nationwide survey involving 4480 Japanese men and women aged ≥40 years was reported in 2003.72 The frequency of all LUTS increased with age. The most common symptoms in men and women are nocturia and daytime frequency. In men, they were followed by weak urinary stream, feeling of incomplete emptying, urinary urgency and urgency incontinence. The most bothersome symptom in men was nocturia. A large-scale study, which recruited 19 165 Western individuals aged ≥18 years, found that 62.5% of men and 66.6% of women were symptomatic, respectively. The most common symptom was nocturia in both men and women.73 The risk factors of LUTS include aging, lifestyles, ED and chronic lifestyle diseases.74-76

The prevalence of BPH depends on its definition, varying from 6% to 12% in Japanese men aged in their 60s and 70s. The risk factors of developing BPH are aging, normally functioning testicles and genetic trait.2 BPH is a progressive disease regardless of race/ethnicity or region.77 Risk factors for BPH progression are aging, lifestyles, prostate volume, elevated PSA, LUTS, impaired QOL and decreased urinary flow rate.78, 79 Lethal comorbidities related to BPH are rare.

7 Pathophysiology

The causes of LUTS in men aged ≥50 years are diverse, including disorders of the prostate and lower urinary tract, pathology of the nervous system, and miscellaneous (Table 1). The most common pathophysiology would be BPH, OAB, underactive bladder, cerebrovascular disorder, polyuria and their combination.1

| 1. Prostate and lower urinary tract |

| Prostate: benign prostatic hyperplasia, prostatitis, prostate cancer |

| Bladder: overactive bladder, underactive bladder, hypersensitive bladder, sensory underactivity, bladder cancer, bladder stones, bladder diverticulum, bacterial cystitis, interstitial cystitis |

| Urethra: urethritis, urethral stricture |

| 2. Nervous system |

| Cerebral: cerebrovascular disorder, dementia, Parkinson's disease, multiple system atrophy, brain tumor, normal pressure hydrocephalus |

| Spinal cord: spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord tumor, spinal infarction, spinal degenerative disease, spina bifida |

| Peripheral nerves: diabetic neuropathy, post-pelvic surgery |

| Other: autonomic hyperactivity |

| 3. Miscellaneous |

| Drug-related, polyuria, sleep disorder, psychogenic, aging |

BPH is highly prevalent in aged men, and associated is with various combinations of voiding and storage symptoms. It arises in the periurethral region of the prostrate, and is histologically comprised of stromal elements of smooth muscle and connective tissue, as well as glandular and luminal epithelial cells. Proliferative factors including sex hormones, inflammation and adrenergic nerve hyperactivity are all causative of prostate enlargement.80 The pathophysiology of BPH-related LUTS would be multifactorial. BOO by the enlarged prostate increases resistance to urinary flow, resulting in voiding symptoms. BOO also induces overdistension, ischemia, inflammation and oxidative stress of the bladder, which subsequently cause denervation hypersensitivity, modulation of detrusor properties and release of urothelial neurotransmitters (e.g. adenosine triphosphate, nitric oxide, prostaglandin and acetylcholine).2 These modulations of urothelium, nerves and detrusor combined with BOO account for a complex of storage or voiding symptoms of BPH. BPH can lead to clinically important complications, such as hematuria, bladder calculi, recurrent urinary tract infections, urinary retention and renal failure.

Independently of the prostate pathology, functional disorders of the bladder, such as OAB, underactive bladder, hypersensitive bladder or sensory underactivity, might result from ischemia, inflammation and oxidative stress of the bladder.81-86 Infection of the bladder or prostate, commonly associated with frequency, urgency and pain, can coexist with bladder stones or BPH. Frequency, urgency and pain might persist, despite antimicrobial medicine in interstitial cystitis, bladder cancer and bladder stones.

Many disorders of the central and peripheral nervous systems, and autonomic nervous system can cause LUTS.87, 88 Other important reasons for LUTS are drug-related adverse events, inappropriate lifestyle (such as overhydration), sleep disturbance and psychogenic disorders.89, 90

8 Diagnosis

Diagnosis of male LUTS is based on clinical history, symptoms and QOL assessment by questionnaires,91, 92 physical examination, urinalysis, serum PSA determination, bladder diary, uroflowmetry, PVR measurement, serum creatinine measurement, and ultrasonography of the prostate or upper urinary tract. Men with “problematic” abnormality should consult urologists. See the Algorithm section for details.

9 Treatment

Treatment for male LUTS and BPH consists of watchful waiting (no therapy), conservative therapy, pharmacotherapy, surgical therapy and others. Conservative therapy is applicable to most cases. Pharmacotherapy is usually indicated for BPH and/or OAB. Combined pharmacotherapy should be reserved for urologists. Surgical therapy is usually directed to men resistant to pharmacotherapy.

The grades of recommendation for treatments (Table 2) were determined through committee discussion and consensus, based on the level of evidence (Table 3), as well as variability of study results, magnitude of effect, clinical applicability, adverse events and cost. Treatment recommendations are summarized in Table 4.

| Grade | Nature of recommendation |

|---|---|

| A | Highly recommended |

| B | Recommended |

| C | No clear recommendation possible |

| C1 | Can be considered |

| C2 | Not recommended |

| D | Recommended not to do |

| Reserved | No recommendation made |

| Level of evidence | Type of evidence |

|---|---|

| 1 | Evidence obtained from multiple RCTs |

| 2 | Evidence obtained from a single RCT or low quality RCTs |

| 3 | Evidence obtained from non-randomized controlled studies |

| 4 | Evidence obtained from observational studies or case series |

| 5 | Evidence obtained from case studies or expert opinions |

| Treatment | Grade |

|---|---|

| Watchful waiting and conservative therapy | |

| Watchful waiting | B |

| Behavior modification | A, B and C1 |

| Pelvic floor exercise, bladder training | A and B |

| Magnetic or electric stimulation | Reserved |

| Pharmacotherapy | |

| BPH | |

| α1-Blockers (α1-adrenoceptor antagonists) | |

| Tamsulosin, naftopidil, silodosin, terazosin, urapidil | A |

| Prazosin | C1 |

| PDE5i | |

| Tadalafil | A |

| Sildenafil, vardenafil | Reserved |

| 5α-Reductase inhibitors | |

| Dutasteride | A |

| Finasteride | Reserved |

| Anti-androgens (chlormadinone, allylestrenol) | C1 |

| Others | |

| Eviprostat®, Cernilton®, Paraprost®, Chinese herbal medicines (Hachimi-jio-gan®, Gosha-jinki-gan®) | C1 |

| OAB and other conditions | |

| Anticholinergics (oxybutynin, propiverine, tolterodine, solifenacin, imidafenacin, fesoterodine) |

B C1 (with BPH) |

| β3-adrenoceptor agonists (mirabegron) | C1 |

| Others (flavoxate, antidepressants, cholinergics) | C1 |

| Alternative medicine | C2 |

| Combined therapy | |

| α1-Blockers and anticholinergics | A |

| α1-Blockers and β3-adrenoceptor agonists | C1 |

| α1-Blockers and 5α-reductase inhibitors | A |

| PDE5i and 5α-reductase inhibitors | Reserved |

| 5α-Reductase inhibitors and anticholinergics or β3-adrenoceptor agonists | C1 |

| Surgical therapy | |

| Subcapsular enucleation | |

| Open prostatectomy | A |

| Laparoscopic or robot-assisted prostatectomy | Reserved |

| Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) | A |

| Transurethral incision of the prostate (TUIP) | A |

| Transurethral enucleation with bipolar system (TUEB®) | B |

| Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP) | A |

| Photoselective vaporization of the prostate by KTP laser (PVP) | A |

| Holmium laser ablation of the prostate (HoLAP) | B |

| Diode laser vaporization of the prostate | C1 |

| Thulium laser resection of the prostate | B |

| Interstitial laser coagulation of the prostate (ILCP) | C1 |

| High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) | C1 |

| Transurethral needle ablation (TUNA®) | C1 |

| Transurethral microwave thermotherapy (TUMT) | B |

| Urethral stent | C1 |

| Prostatic urethral lift, water vapor, prostatic arterial embolization | Reserved |

| Others | |

| Indwelling catheterization | C1 |

| Intermittent catheterization | B |

9.1 Watchful waiting (grade B)

BPH without bothersome symptoms or complications might require no treatment, as long as appropriate follow up is undertaken (level 4).93

9.2 Conservative therapies

Behavior modification (A, B and C1)

Weight reduction in obese men decreased urinary incontinence (level 1; grade A)14, 15. Integrated behavior therapy consisting of education, avoiding excessive fluid intake, bladder training and other measures significantly improved storage symptoms (level 2; grade B).16, 17 Exercise, dietary modification or smoking cessation can improve LUTS (level 4; grade C1).94 These lifestyle changes are the least invasive and inexpensive.

Pelvic floor exercise, bladder training (A and B)

Pelvic floor exercise and bladder training, especially directed by physiotherapists, improved OAB symptoms in men (level 2; grade B)18, 95 and post-prostatectomy incontinence (level 1; grade A).96

Magnetic or electric stimulation (reserved)

Pelvic floor electrical stimulation has efficacy evidence for post-prostatectomy incontinence (level 2).97 Bladder interferential stimulation alone is approved in Japan.

9.3 Pharmacotherapy for BPH

α1-Blockers (A)

By inhibiting contractions mediated by prostatic α1-adrenoceptors, α1-blockers reduce BOO and bring about prompt symptom improvement; 30–40% (4–6 point) reduction in the average IPSS, and 20–25% (2.0–2.5 mL/s) increase in Qmax (level 1).1, 2 Tamsulosin, naftopidil, silodosin, terazosin, urapidil and prazosin are approved in Japan, and are apparently of comparable efficacy. The former three have shown ample evidence for efficacy.21, 24, 25, 98-103 Postural hypotension and asthenia can occur as rarely as a placebo (4–10%). Significant adverse events include ejaculatory dysfunction and intraoperative floppy iris syndrome.

PDE5i (A)

PDE5i relaxes the smooth muscle of the prostate and urethra by inhibiting degradation of cyclic guanosine monophosphate and increasing nitric oxide concentration, improving LUTS associated with BPH (level 1).104 The average IPSS decreases by 2.35–4.21 points, whereas Qmax shows marginally or no significant increase of 0.01–1.43 mL/s.62, 105-108 Tadalafil alone is approved in Japan.29, 109, 110 Administration to men with high cardiovascular risks or combined use with nitrate is contraindicated.111

5α-Reductase inhibitors (A)

5α-Reductase inhibitors suppress conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, reducing biological activities of the prostate and relieving LUTS associated with BPH.50, 112, 113 A Japanese phase III trial of dutasteride in men with prostatic volume ≥30 mL showed an IPSS reduction by 5.3 points, Qmax increase by 2.2 mL/s and prostatic volume reduction by 22% (level 1).114 Sexual dysfunction can occur as an adverse event, and PSA levels decrease approximately by half. Dutasteride alone is approved in Japan.

Anti-androgens (C1)

Chlormadinone and allylestrenol suppress prostate growth by inhibiting pituitary secretion of gonadotropin, and testosterone action in the prostate. The efficacy is not supported by a high level of evidence (level 2).2, 115 Various adverse effects including severe sexual dysfunction can occur.

Others (C1)

Outdated or low-level evidence supports the efficacy for medicines of plant extracts and Chinese herbal medicines (level 2). Adverse reactions are rare and minor.2, 116, 117

9.4 Pharmacotherapy for OAB and other conditions

Anticholinergics (B, C1)

Anticholinergics approved in Japan (oxybutynin, propiverine, tolterodine, solifenacin, imidafenacin and fesoterodine) have a high level of evidence for improving OAB symptoms, although the study cohorts were mostly of women (level 1; grade B).45 For men with BOO, the efficacy is limited (level 1; grade C1), and the safety concern, such as voiding difficulty, is not resolved.118 α1-Blockers should be first administered to OAB with BPH, and anticholinergics are to be combined when α1-blocker monotherapy is insufficient (level 1).41-47

β3-Adrenoceptor agonists (C1)

Mirabegron reduces detrusor tonus by stimulating β3-adrenoceptors. Its efficacy for OAB is shown for women and men,119-124 but limited for men with BPH (level 3).125 Safety concerns remain for voiding difficulty, although dry mouth and constipation, often seen in anticholinergics, are rare.

Flavoxate and antidepressants (C1)

There is some evidence for flavoxate and antidepressants improving LUTS (level 2), although they are not approved for BPH or OAB. Drowsiness is an adverse event of antidepressants.1

Cholinergics (C1 for urologists, C2 for non-urologists)

Cholinergics are approved for voiding difficulty as a result of detrusor underactivity; however, the efficacy is negated (level 1).1 Adverse events, such as diarrhea, angina and especially cholinergic crises, are serious concerns. Cholinergics are contraindicated for BOO. They can be used by urologists with special care.

9.4.1 Alternative medicine (C2)

High-level evidence to support both efficacy and inefficacy is mixed (level 1). Inconsistent efficacy results, uncertain safety and high cost born by patients are concerns (see CQ 10).1

9.5 Combined pharmacotherapy

α1-Blockers and anticholinergics (A)

See CQ 11.

α1-Blockers and β3-adrenoceptor agonists (C1)

See CQ 11.

α1-Blockers and 5α-reductase inhibitors (A)

See CQ 12 and CQ 13.

PDE5i and 5α-reductase inhibitors (reserved)

See CQ 14.

5α-Reductase inhibitors and anticholinergics or β3-adrenoceptor agonists (C1)

The combination is potentially an alternative therapy for OAB associated with BPH, but not supported by sufficient evidence (level 4).126, 127

9.6 Surgical therapy

Surgery is indicated for persistent LUTS despite conservative or medical therapies, or BPH-related comorbidities, such as urinary retention. Less invasive surgery using new energy sources is presently evolving. Resection/vaporization of the enlarged prostate appear to be more effective. Selection of surgical modalities depends on the patient's characteristics, performance of equipment available and the surgeon's experience.

Enucleation

(a) Open surgery (A)

This classic technique is a standard surgery for en bloc enucleation of large prostates.128, 129

(b) Laparoscopic and robot-assisted laparoscopic surgeries (reserved)

These modalities appear to be less invasive than open surgery, although evidence for long-term efficacy and safety is lacking.130-132

TURP: Monopolar or bipolar (A)

TURP is the standard surgical technique usually used for moderate size prostates (30–80 mL). Hemorrhage or hyponatremia by irrigation fluids (TUR syndrome) can occur.133-135 Bipolar TURP is less likely to induce TUR syndrome.136, 137

Transurethral incision of the prostate (A)

This technique has short-term efficacy comparable with TURP, with a lower risk of complications. It is applicable to relatively small size prostates (<30 mL).134, 138, 139

Transurethral enucleation with bipolar system (B)

It is applicable to moderate-to-large size prostates, and is as efficacious as TURP or open enucleation surgery.140-142

Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (A)

Holmium laser has a high absorbance rate by water. Sufficient evidence supports its efficacy comparable with TURP or open surgery.143-145

Photoselective vaporization of the prostate by KTP laser (A)

KTP laser has a high absorbance rate by hemoglobin. There is sufficient evidence for its efficacy comparable with TURP or open surgery. Men taking anti-coagulants can be safely operated.146-148

Diode laser vaporization of the prostate (C1)

Diode laser is absorbed by water and hemoglobin. Evidence for long-term efficacy in comparison with TURP or open surgery is not sufficient.149, 150

Thulium laser resection vaporization of the prostate (B)

Evidence supports its long-term efficacy comparable with TURP or open surgery. Men taking anti-coagulants can be safely operated.151-154

Interstitial laser coagulation of the prostate (C1)

The treatment is as effective as TURP for the short-term, although almost half of patients require further treatments in long-term follow up.2

Transrectal high-intensity focused ultrasound (C1)

Reports on efficacy and safety are limited. Re-intervention is required in half of cases.2

Transurethral needle ablation (C1)

Medium-term efficacy is comparable with TURP. Re-treatment or perioperative irritative symptoms are seen in nearly half of cases.2

Transurethral microwave therapy (B)

Medium-term efficacy has been repeatedly shown, even for large prostates. Almost half of cases require further interventions.2

Urethral stent (C1)

It is indicated for high-risk or surgery-contraindicated patients. Complications that require stent removal can occur.155, 156

Prostatic urethral lift (reserved)

Efficacy almost comparable with TURP is shown. Some cases require further interventions.157-159 It is not approved in Japan.

Water vapor (reserved)

There is some evidence to support efficacy, although long-term efficacy is uncertain.160 It is not approved in Japan.

Prostatic arterial embolization (reserved)

Evidence to support efficacy is lacking. It would be an experimental therapy.161

9.7 Other treatments

Indwelling catheterization (C1)

It is indicated if other treatments are impractical. High complication rates and/or QOL impairment are associated.8, 162

Intermittent catheterization (B)

Compared with indwelling catheterization, urinary tract infection is less frequent and early recovery of bladder function is more likely.162

10 BPH treatment and sexual function

Treatments for BPH can impact adversely on sexual function. Surgical interventions often result in ejaculatory dysfunction60, 163; α1-blockers sometimes cause ejaculatory dysfunction24; and 5α-reductase inhibitors and anti-androgens result in multiple sexual dysfunctions, being more severe for the latter.164 See CQ 15.

11 Clinical study

This section makes some recommendations for clinical studies on BPH treatment.2

11.1 Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Men aged ≥50 years, with symptoms suggestive of BPH (i.e. IPSS ≥8) and QOL impairment (i.e. QOL score ≥2), with prostate enlargement (i.e. PV ≥20 mL) and lower urinary flow rate (i.e. Qmax <15 mL/s), would be candidates for the study. Exclusion criteria might include suspicion or presence of diseases other than BPH, persisting effects of precedent treatments or conflicts with the characteristic of the treatment.

11.2 Criteria for severity and therapeutic efficacy

Severity and efficacy can be assessed by the values or the value changes of IPSS, QOL index, scores of other questionnaires (BPH impact index, King's Health Questionnaire and Short Form-36), prostate volume, or flow rate. The cut-offs of these values for severity or efficacy criteria have been suggested.

Conflict of interest

Yukio Homma received research grants from Astellas, Asahikasei, DaiichiSankyo, Ono, Takeda and Nippon Shinyaku, and received lecture fees from Astellas and Integral; Momokazu Gotoh received research grants from Astellas, DaiichiSankyo, Ono and Takeda, and received lecture fees from Astellas, Pfizer, Kissei, Kyorin, Taiho and DaiichiSankyo; Akihiro Kawauchi received research grants from Astellas; Yoshiyuki Kojima received research grants from Takeda and received lecture fees from Astellas; Naoya Masumori received research grants from Astellas and Takeda, and received lecture fees from Astellas, Nippon Shinyaku, Asahikasei, Astra Zeneca and Kissei; Atsushi Nagai received research grants from Nippon Shinyaku, Takeda, Astellas, Ono and Kissei, and received lecture fees from Nippon Shinyaku and Pfizer; Hideki Sakai received research grants from Astellas, Takeda and Pfizer, and received lecture fees from Takeda; Satoru Takahashi received research grants from Astellas, Takeda, Nippon Shinyaku and Yamada-yohozyo, and received lecture fees from Astellas, Pfizer and Nippon Shinyaku; Osamu Ukimura received research grants from Astellas, Takeda, Nippon Shinyaku and Glaxosmithkline; Tomonori Yamanishi received research grants from Astellas; Osamu Yokoyama received research grants from Astellas, Taiho, Kissei, DaiichiSankyo, Ono, Pfizer, Bayer and Nippon Shinyaku, and received lecture fees from Pfizer, Astellas, Hisamitsu, Nippon Shinyaku, Kyorin, Glaxosmithkline, Kissei and Ono; Masaki Yoshida received grant from Astellas, and received lecture fees from Astellas, Kissei, Kyorin, Nippon Shinyaku; Tadanori Saitoh and Kenji Maeda have no conflict of interest. Funding for the committee meetings was provided by JUA.