Editorial Comment from Dr Catena, Dr Colussi and Dr Sechi to Preoperative masked renal damage in Japanese patients with primary aldosteronism: Identification of predictors for chronic kidney disease manifested after adrenalectomy

Mounting evidence indicates that primary aldosteronism, one of the commonest forms of curable hypertension, is associated with a variety of organ complications that are beyond what could be merely expected from elevated blood pressure levels.1 Appropriate management of this endocrine condition results in effective prevention of cardiovascular and renal damage,2 with evidence that applies to both surgical and medical treatment.3, 4 It is known that only approximately one-third of patients with primary aldosteronism can withdraw antihypertensive agents after treatment and, in this context, the kidney seems to play a crucial role inasmuch as renal function becomes one of the main determinants of the blood pressure response.5 Current evidence shows that the renal disease of primary aldosteronism could be seen as a two-stage process that recognizes distinct pathophysiological mechanisms.6 In the early stage, intrarenal hemodynamic adaptation to increased extracellular volume7 leads to glomerular hyperfiltration that compensates for the tubular effect of aldosterone and restores sodium balance. As previously shown, this stage is largely and rapidly reversible with both surgical and medical treatment.8, 9 In the advanced stage, intrarenal vascular damage ensues and progressive renal impairment might occur as a result of glomerular ischemia.

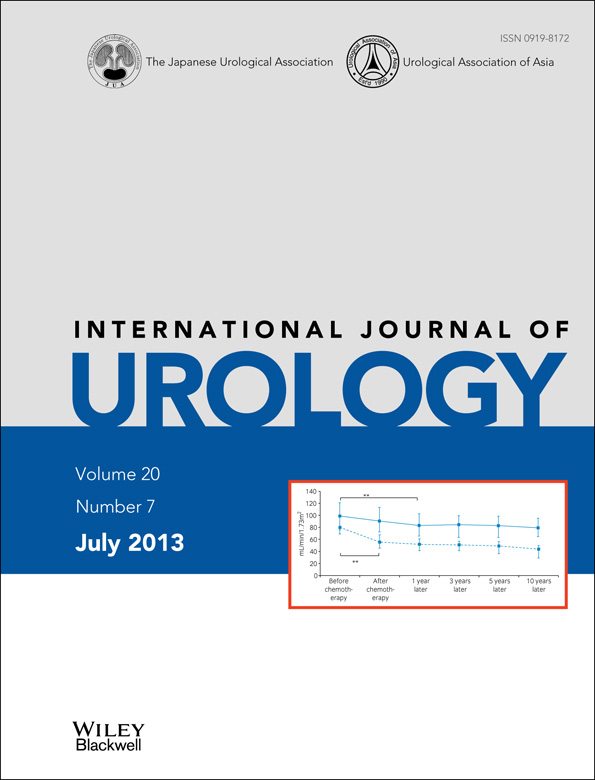

In this issue of the Journal, Utsumi et al.10 report the results of a retrospective analysis of patients with primary aldosteronism in whom the outcome of glomerular filtration (GFR) was investigated after adrenalectomy. Although important markers of renal damage, such as albuminuria, were not measured by the authors, and the follow up of 2 years was too short to permit an assessment of outcome in the longer term, the findings of the study do support some important points. First, pretreatment levels of renin were significantly higher in primary aldosteronism patients with lower GFR. This is in agreement with previous studies that have shown the lack of complete renin suppression as the hallmark of an advanced stage of renal disease in primary aldosteronism11 that is associated with a lesser probability of cure. Second, treatment of primary aldosteronism was followed by a decrease in GFR that occurred in the first 6 months and was significantly greater in patients with higher GFR at baseline, reflecting correction of the intrarenal hemodynamic adaptation present in the earlier stages of disease. Third, the probability of reaching GFR levels below 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (stage 3 of chronic kidney disease) was greater in patients with lower baseline GFR levels. In fact, more than half of the patients with baseline GFR between 60 and 89 mL/min/1.73 m2 reached stage 3, whereas none of the patients with baseline GFR of 90 mL/min/1.73 m2 or more did. Fourth, in those patients who developed stage 3 renal disease, Utsumi et al. identified dyslipidemia as an independent predictor of renal function worsening.

Today, we are aware that the involvement of the kidney in primary aldosteronism is extremely important, because structural kidney damage is associated with worse outcome, both in terms of blood pressure response to treatment and the probability of developing progressive renal failure. It is good to know, however, that this type of structural damage takes a rather long time to occur as early functional changes are largely reversible with treatment. The findings of the study by Utsumi et al. reinforce this evidence and once again underline the importance of an appropriate timing in the identification of these patients in order to prevent renal deterioration and optimize the clinical benefits of treatment.

Conflict of interest

None declared.