The criterion-related validity of conscientiousness in personnel selection: A meta-analytic reality check

Abstract

A key finding in personnel selection is the positive correlation between conscientiousness and job performance. Evidence predominantly stems from concurrent validation studies with incumbent samples but is readily generalized to predictive settings with job applicants. This is problematic because the extent to which faking and changes in personality affect the measurement likely vary across samples and study designs. Therefore, we meta-analytically investigated the relation between conscientiousness and job performance, examining the moderating effects of sample type (incumbent vs. applicant) and validation design (concurrent vs. predictive). The overall correlation of conscientiousness and job performance was in line with previous meta-analyses (). In our analyses, the correlation did not differ across validation designs (concurrent: ; predictive: ), sample types (incumbents: ; applicants: ), or their interaction. Critically, however, our review revealed that only a small minority of studies (~12%) were conducted with real applicants in predictive designs. Thus, barely a fraction of research is conducted under realistic conditions. Therefore, it remains an open question if self-report measures of conscientiousness retain their predictive validity in applied settings that entail faked responses. We conclude with a call for more multivariate research on the validity of selection procedures in predictive settings with actual applicants.

Practitioner points

-

Research on the predictive validity of conscientiousness is almost exclusively conducted with incumbents and criterion data gathered at the same time as test data.

-

Such studies likely underestimate the detrimental effects of faking and personality change across time.

-

Predictive studies with real applicant samples are scarce.

-

Self-report personality measures should be used with caution if faking was expected.

-

In general, a stronger emphasis on incremental validity instead of individual predictors is desirable.

1 INTRODUCTION

The application of personality tests in personnel selection is presumably legitimized by several meta-analyses that consistently report small to moderate associations between self-report measures of personality and measures of job performance (e.g., Barrick et al., 2001; He et al., 2019; Judge et al., 2013; Salgado, 1997; Shaffer & Postlethwaite, 2012). The largest and most generalizable correlations have been reported for the personality trait conscientiousness, with raw correlations around = .15 and disattenuated correlations around ρ = .24 (e.g., He et al., 2019). To provide unbiased and generalizable estimates, however, meta-analyses must ensure that primary studies are representative of the settings towards which generalization is sought (Cooper et al., 2019). Morgeson et al. (2007b, p. 1045) rightly stated that “only studies that use a predictive model with actual job applicants should be used to support the use of personality in personnel selection.” However, reading the pertinent literature and reference sections of published meta-analyses (e.g., Judge et al., 2013; Salgado, 1997; Tett et al., 1991) conveys the impression that research primarily investigates job incumbents (or students) in concurrent designs. We assume this is not because researchers are unaware of the inadequacies of such studies but because predictive studies are often costly, and access to actual applicant samples can be difficult.

Sample and design characteristics have been discussed as important moderators of validity.1 However, the evidence has remained scarce and inconclusive due to an insufficient number of primary studies to analyze (Van Iddekinge & Ployhart, 2008; see also Table 1). In the present study, we revisited this question based on a broader database covering the last 40 years. Thereby, we were less interested in the effects of sample type or study design per se. Instead, we argue that different processes operate in different samples and designs, potentially influencing personality measurement and thus criterion validity. As we will elaborate more comprehensively in the following sections, we argue that both faking (Ziegler et al., 2011) and personality change (Roberts et al., 2006; Wille et al., 2012) are more prevalent in applicant samples with predictive validation designs than in concurrent studies with incumbents.

| Concurrent/predictive | Incumbent/applicant | |

|---|---|---|

| Conscientiousness and overall job performance | ||

| Barrick and Mount (1991) | – | – |

| Barrick et al. (2001)a | – | – |

| Darr (2011) | – | Coded but not reported |

| Dudley et al. (2006) | – | Coded but not reported |

| He et al. (2019)a | – | – |

| Hogan and Holland (2003) | 41/2 | – |

| Hough (1992) | – | – |

| Hurtz and Donovan (2000) | – | – |

| Oh et al. (2011) | 14/2 | 16/0 |

| Judge et al. (2013) | – | – |

| Rojon et al. (2015) | – | – |

| Salgado (1997) | – | – |

| Salgado (2003) | – | – |

| Shaffer and Postlethwaite (2012) | 112/7 | 117/3 |

| Shaffer and Postlethwaite (2013) | – | – |

| van Aarde et al. (2017) | – | – |

| Wilmot and Ones (2019)a | – | – |

| Other/multiple constructs or alternative job-related criteria | ||

| Bartram (2005) | 21/7 | – |

| Berry et al. (2007) | – | – |

| Chiaburu et al. (2011) | – | – |

| Huang et al. (2014) | 64/1 | – |

| Ilies et al. (2009) | – | – |

| Judge et al. (2002) | – | – |

| Lee et al. (2019) | – | – |

| Ones et al. (1993) | 135/79 | 135/43 |

| Pletzer et al. (2019) | – | – |

| Salgado (2002) | – | – |

| Salgado and Táuriz (2014) | – | – |

| Schmitt et al. (1984) | 153/213 | – |

| Tett et al. (1991) | – | 81/12 |

| Van Iddekinge et al. (2012) | 38/32 | 47/24 |

| Woo et al. (2014) | – | – |

- Note: –, design or sample characteristics were not considered.

- a Second-order meta-analysis.

In the present study, we first describe our view of a typical personnel selection process and derive requirements for primary studies. Next, we review the prevalence of sample types and study designs in primary studies on the validity of conscientiousness to predict job performance over the last 40 years. Finally, we meta-analytically investigate the validity of conscientiousness to predict job performance. Thereby, we specifically focus on the moderating effects of sample type, study design, and, most importantly, the interaction of both moderators.

1.1 Characteristics of a common personnel selection process

In our view, a typical personnel selection process has several key characteristics. First, there are more applicants than positions to be filled, making a selection based on some attributes of applicants inevitable in the first place. Second, the selection decision depends on the performance of applicants in the selection procedure (e.g., personality test). Consequently, applicants are highly motivated to perform well in the procedure and portray what they think is a favorable picture of themselves to get the job. While there are certainly exceptions to this (e.g., applications enforced by employment agencies threatening to withdraw welfare), we argue that it is prudent to assume that applicants want to receive a job offer in the vast majority of personnel selection procedures. Third, a time lag between the time of the selection process and the collection of criterion data (e.g., supervisory ratings of job performance) is inevitable. Obviously, the newly hired employee (or the old employee in a new position) must have had the opportunity to demonstrate observable behavior (e.g., sell, build, or invent things), which can serve as an indicator of job performance. In sum, then, selection processes inevitably involve real applicants and predictive validation designs. In the following, we review the prevalence of sample types (incumbents vs. applicants) and study designs (concurrent vs. predictive) in previously published meta-analyses.

1.2 Incumbent versus applicant samples

Incumbents and applicants likely differ in key characteristics. Relative to job incumbents, job applicants put more effort and motivation into the tests (Arvey et al., 1990) and distort their responses to portray a favorable image of themselves (Griffith & Converse, 2011). This is conclusive because, for job applicants, the testing process usually constitutes a high-stakes situation with far-reaching consequences for their personal and vocational life. In turn, for job incumbents with secure jobs, the consequences of poor performance are relatively less essential. This intentional distortion to portray a favorable picture of oneself to achieve personal goals has been termed “faking” (Ziegler et al., 2011). According to several studies, around 30%–50% of applicants fake personality tests (e.g., Donovan et al., 2014; Griffith et al., 2007). Therefore, the occurrence of faking must be considered the rule rather than the exception in applicant samples.

On the one hand, some authors argued that faking does not affect the validity of personality measures (e.g., Hough, 1998b; Komar et al., 2008; Tett & Simonet, 2021; Weekley et al., 2004). On the other hand, extensive empirical evidence suggests that faking affects the mean structure, the covariance structure and criterion validity of self-report measures of personality (e.g., Christiansen et al., 2021; Donovan et al., 2014; Geiger et al., 2018; Krammer et al., 2017; MacCann et al., 2017; Pauls & Crost, 2005; Schmit & Ryan, 1993). Mean shifts are commonly observed as a consequence of faking (Birkeland et al., 2006). More importantly, faking will alter the rank order of participants and thus the construct validity of self-reports and also the criterion validity of personnel selection decisions based upon such reports (e.g., Anglim et al., 2018; Donovan et al., 2014; Jeong et al., 2017). Even if faking only alters scores slightly on average, this can substantially affect top-down selection decisions (Donovan et al., 2014; Pavlov et al., 2018); if only three out of 100 applicants fake and thus prevail in the process for three vacancies, the proportion of persons hired based on invalid personality scores is 100%. Changes in rank orders occur because persons fake to a different extent because they differ in the extent to which they are willing and able to fake (Boss et al., 2015; Geiger et al., 2018, 2021; Krammer, 2020; Pavlov et al., 2018). In instructed faking studies, correlations below .50 have been reported between honest and faked personality scores (e.g., Galić & Jerneić, 2013; Ng et al., 2020; Pavlov et al., 2018) and faking seemingly affects the measurement invariance of personality tests (e.g., Krammer et al., 2017). However, changes in rank order seem to be less pronounced in applicant samples than in instructed faking studies (Hu & Connelly, 2021). If within-person correlations are weak, honest and faked personality scores may represent a jingle fallacy (Kelley, 1927), in that they are assigned the same name (e.g., conscientiousness) but what is actually measured is partly or fundamentally different. If personality, as measured in low-stakes settings, differs markedly from personality as measured in high-stakes settings, the question arises as to which kind of construct is measured in primary studies of seminal meta-analyses relating personality scores to job performance.

The type of sample has rarely been investigated or reviewed as a potential moderator of validity. In a meta-analysis, Tett et al. (1991) initially found higher validities for incumbents than for recruits, but this effect was due to a single study with an outsized influence on the effect (the sample had over 4000 military recruits). After the removal of this study, only 11 studies with 814 subjects remained, and the difference between the sample types was found to be nonsignificant. Darr (2011), as well as Shaffer and Postlethwaite (2012), coded sample type but were unable to perform moderator analyses because the number of applicant samples was far too low (e.g., three applicant studies in Shaffer & Postlethwaite, 2012). Van Iddekinge et al. (2012) investigated the validity of self-report measures of integrity. They found descriptively lower validity estimates in applicant (ρ = .15) than in incumbent samples (ρ = .20), but the difference was not significant. As our broader review in Table 1 shows, most published meta-analyses on the criterion-related validity of personality measures do not consider whether the included samples comprise applicants or incumbents.

In sum, the difference in the predictive validity of personality in applicant versus incumbent samples is inconclusive, but points towards slightly lower validity estimates in applicant samples than in incumbent samples. This conclusion supposedly applies to self-report measures of personality more broadly and conscientiousness more specifically. On a side note, the lack of attention to design and sample characteristics is also prevalent in investigations of the validity of cognitive ability (Schmitt & Sinha, 2011). However, faking (good) is less of an issue in tests of maximum performance (but see Steger et al., 2018 for evidence concerning problems with unproctored online testing).

1.3 Concurrent versus predictive validation designs

In concurrent validation designs, the predictor and criteria data are collected at the same time, whereas in predictive designs, criteria are collected at a later time point. Evidently, the validation design and sample are not independent—concurrent validation studies cannot be conducted with job applicants as their criterion data are not available at the time of testing. Concurrent designs are cross-sectional in nature and therefore incompatible with the overarching predictive purposes of personality testing in personnel selection, which is to predict an applicant's future performance based on the current data.

Predictive designs, in turn, exist in different variants, but all have in common that some time passes between assessing predictors and gathering criterion data (Guion & Cranny, 1982). Therefore, predictive studies can comprise both job incumbents and job applicants, but concurrent studies can only comprise job incumbents. The temporal distance in longitudinal studies can change the association of initial personality assessment and subsequent criterion measure. Personality traits have long been viewed as invariant over time. However, personality research has increasingly moved to acknowledge systematic age-related changes in personality (Roberts et al., 2006) and particularly following significant life events (Bleidorn et al., 2018; Woods et al., 2013). Besides private events (e.g., marriage and parenthood), work-related events such as entering the work force or taking on a new job role (Wille et al., 2012), have been shown to change personality traits. Thus, the trait levels at the time of hiring can differ from the trait levels that shape behavior in the further career. If that's the case, the predictive power of initial personality measurement should decrease as a function of time since recruitment. Further, in predictive applicant samples with selection, job performance criteria can only be assessed for the (usually small) subsample of hired individuals, requiring corrections for range restriction to obtain unbiased estimates of predictive validity.

The type of design has been discussed as an important characteristic of validation studies (Van Iddekinge & Ployhart, 2008). In a 40-year-old meta-analysis, Schmitt and colleagues (1984) found minimally lower criterion-related validities for aggregates of personality scales in predictive (r = .30) relative to concurrent designs (r = .34), and predictive designs with selection (r = .26). Hough (1998a) reported a predictive raw correlation of dependability and job proficiency that was .05 lower than the concurrent validity estimate, although this difference is unlikely to be significant. As Van Iddekinge and Ployhart (2008) rightly point out, this might not seem much but given that observed validity estimates are generally low, this amounts to a substantial decrease in explained variance. Because Hough (1998a) based her analyses solely on military samples, the generalizability of the results might be limited. In their meta-analysis on the validity of integrity tests, Van Iddekinge et al. (2012) did not find significant differences between predictive (ρ = .17) and concurrent (ρ = .19) studies.

As our review illustrates, several other meta-analyses have coded the study design of primary studies (Table 1). However, they have not reported moderator analyses due to the literature's low prevalence of predictive validation studies. Concerning sample type as moderator, the effect of the study design is inconclusive. If anything, the extant literature suggests slightly lower validity estimates in predictive than in concurrent designs.

1.4 The present study

Taken together, there is a discrepancy between the alleged awareness that only predictive studies with real applicants are suitable to investigate the validity of self-report measures of personality in personnel selection and common practice. In fact, barely any previous meta-analyses had a sufficient number of samples to investigate validity under what we would call realistic conditions. The present study aims to fill this gap.

2 METHODS

2.1 Literature search

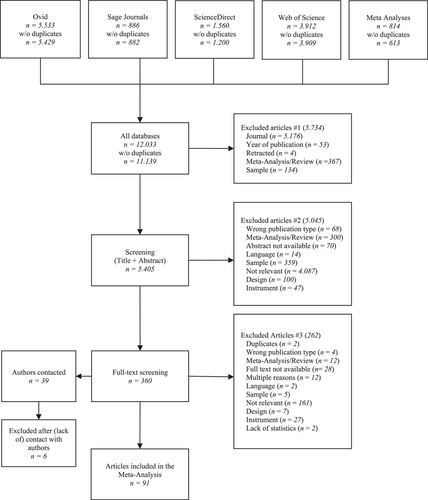

The literature search was conducted in July 2020. We searched OVID (PsyArticles, PsyINFO, and PSYNDEX), Sage Journals (Social Sciences and Humanities), ScienceDirect, Web of Science (Core Collection without Chemical Indexes) and the reference sections from the meta-analyses reported in Table 1 for journal articles written in English and published between 1980 and 2020. To be inclusive, we first developed a broad taxonomy of conscientiousness (see Appendix A). Terms from this taxonomy were subsequently searched for in combination with “job performance,” “work performance,” performance rating,” or “overall performance” (see OS1). We searched in titles, abstracts, and keywords. After the removal of duplicates, the initial search led to 10,713 articles. Figure B1 (Appendix B) provides a PRISMA chart of the literature search.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Concerning the predictor, we included studies that reported at least one self-report measure of conscientiousness or a facet thereof. We restricted the analysis to conscientiousness because it is supposedly the most important personality factor in personnel selection and it is presumably the most studied personality factor with the richest database. We excluded forced-choice measures from the analysis for methodological reasons (Brown & Maydeu-Olivares, 2013; Bürkner et al., 2019). Regarding the criterion, studies had to report a measure of overall job performance provided by a supervisor. Other sources (e.g., peers) or types of performance (e.g., OCB) were not included. Studies had to include some estimate of the association between the predictor and the criterion that could be transformed to a bivariate correlation. We only included studies that reported individual-participant data and excluded studies that reported group-level or unit-level analyses. Concerning sample and design, we included concurrent and predictive studies with job applicants or job incumbents conducted in a field (i.e., organizational) setting. Simulation studies or studies with student samples were not considered. The comprehensive coding manual is provided in OS2.

2.3 Data extraction

Data screening and extraction were performed in three steps. In a preliminary step, one rater assessed all articles for general viability. This was necessary as the breadth of the search terms led to a multitude of articles from other fields within (e.g., psychotherapy) and outside of psychology (e.g., chemistry). Next, three additional raters underwent training and subsequently helped to screen the remaining articles based on their abstract. Finally, 360 studies were considered for full-text screening, of which 92 articles were included in the final analysis. All articles were double-coded by four trained psychology students; one rater coded all studies, and three other raters coded a subset. The proportion agreement for the main categorical variables ranged between 0.92 and 1.00. The intra-class correlation coefficient for the main continuous variables was between 0.92 and 1.00 (see OS3 for comprehensive tables of reliability estimates for all variables). Discrepancies were discussed and resolved before further analysis.

2.4 Data analytic strategy

Unreliability in the measurement, as well as range restriction, can attenuate the observed predictive validity estimates. Comprehensive information about reliability estimates in the initial sample, the selected sample, and selection ratios are necessary to adequately correct for such attenuating factors (Sackett et al., 2021). Unfortunately, most primary studies did not report sufficient information to perform suitable corrections for either reliability or range restriction. In fact, only three studies reported selection ratios. Therefore, as we concur with Sackett et al. (2021) evaluation that common correction methods tend to inflate validity estimates if based on insufficient data, and their principle of conservative estimation, we chose only to report raw estimates.

When studies reported multiple measures of the same construct (e.g., two measures of conscientiousness which could be classified under the same facet of conscientiousness), we computed composite scores (Schmidt & Hunter, 2015; as implemented in the composite_r_scalar function of the psychmeta package). Correlations were then transformed to Fisher's z values, which were the basis for the random-effects meta-analyses. For ease of interpretation, final estimates were converted back into correlation coefficients (Cooper et al., 2019). We quantified heterogeneity and uncertainty in effect sizes using τ² using the restricted maximum likelihood estimator (REML), Higgins I², and prediction intervals (Cooper et al., 2019; IntHout et al., 2016). When testing individual coefficients, we used the method proposed by Knapp and Hartung (2003) to adjust standard errors. To identify outliers and influential studies, we used Baujat plots (Baujat et al., 2002) and influence plots (Viechtbauer & Cheung, 2010). Publication bias was investigated via funnel plots and Egger's regression test (Sterne & Egger, 2005).

All analyses were performed in R (version 4.0.4; R Core Team, 2020). Data handling and visualization were performed with packages of the tidyverse (version 1.3.1, Wickham et al., 2019). Descriptive and psychometric statistics were computed with the summarytools package (version 0.9.9; Comtois, 2021) and the psych package (version 2.0.12; Revelle, 2020), interrater reliability was computed with the psych package and the irr package (version 0.84.1; Gamer et al., 2019), composite scores were computed with the psychmeta package (version 2.4.2; Dahlke & Wiernik, 2019), and the meta-analysis was performed with the metafor package (version 2.4-0; Viechtbauer, 2010). All data, syntax, and materials are available at https://osf.io/87gyr/.

3 RESULTS

We identified 132 effect sizes from 115 unique samples reported in 91 articles with a total of 32,499 participants. As Table 2 illustrates, the vast majority of correlations were for the association of a global measure of conscientiousness with job performance in concurrent studies with job incumbents. Given the low number of studies for facets of conscientiousness and levels of the main moderators, we restrained all further analyses to the global measure of conscientiousness. Two studies were excluded due to the outlier/influence analysis (we report all results, including the two studies, in OS4). Neither the funnel plots nor Egger's regression test indicated meaningful publication bias (see OS5).

| k | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Conscientiousness | ||

| Global | 104 | 78.79 |

| Orderliness | 6 | 4.55 |

| Industriousness | 15 | 11.36 |

| Self-Control | 3 | 2.27 |

| Responsibility | 4 | 3.03 |

| Study design × sample type | ||

| Concurrent | 97 | 73.48 |

| Incumbent | 93 | 70.40 |

| Internal applicant | 4 | 3.03 |

| External applicant | 0 | 0 |

| Predictive | 35 | 26.52 |

| Incumbent | 20 | 15.20 |

| Internal applicant | 1 | 1.33 |

| External applicant | 14 | 10.60 |

- Note: k, number of correlations.

3.1 Overall effect

In the first step, we estimated the overall association of conscientiousness with job performance as a replication of previous meta-analyses. The raw estimate = .17 [.15, .19] was in line with previously reported validity estimates (e.g., Barrick et al., 2001; He et al., 2019; Judge et al., 2013; Shaffer & Postlethwaite, 2012; Wilmot & Ones, 2019). All indices of heterogeneity indicated a fair amount of heterogeneity among the true effects (Q = 216.6, df = 101, p < .001; τ = .07; I² = 52.61). Accordingly, we investigated sample, design, and the interaction of both as sources of heterogeneity in a moderation analysis (Table 3).

| 95% CI | 95% PI | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | k | n | LB | UB | LB | UB | Q | τ | I² | |

| Overall | 102 | 23,305 | .17 | .15 | .19 | .03 | .31 | 216.6** | .07 | 52.61 |

| Sample | 210.1** | .07 | 52.06 | |||||||

| Applicants | 10 | 2497 | .14 | .08 | .20 | −.01 | .29 | |||

| Incumbents | 92 | 20,808 | .18 | .16 | .20 | .04 | .31 | |||

| Design | 212.9** | .07 | 52.43 | |||||||

| Predictive | 24 | 4173 | .15 | .11 | .20 | .01 | .29 | |||

| Concurrent | 78 | 19,132 | .18 | .16 | .20 | .04 | .31 | |||

| Sample × Design | 209.9** | .07 | 53.06 | |||||||

| Appl./Pred. | 9 | 2497 | .16 | .10 | .22 | .01 | .31 | |||

| Incumb./Pred. | 15 | 1902 | .14 | .08 | .20 | −.01 | .29 | |||

| Incumb./Concur. | 77 | 19,336 | .18 | .16 | .20 | .04 | .31 | |||

- Abbreviations: 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; I², ratio of true heterogeneity to total variation; k, number of correlations; LB, lower bound; n, total sample size; 95% PI, 95% prediction interval; Q, homogeneity statistic; r, mean estimate of uncorrected correlations; τ2, variance of the true effect sizes; UB, upper bound.

- ** p < .001.

3.2 Moderator analyses

3.2.1 Sample type

To test the moderating effect of sample type, we estimated a meta-regression where sample type was dummy-coded and the applicant samples served as the reference group. Estimates were = .14 [−.01, .29] for applicants and = .18 [.04, .31] for incumbents, respectively. An omnibus test indicated that the small difference between effect sizes for the applicant and incumbent samples was not significant, F (1, 100) = 1.03, p = .31.

3.2.2 Study design

The moderating effect of the study design was tested analogously. The concurrent designs served as the reference group. Estimates were = .18 [.04, 0.31] for concurrent designs and = .15 [.01, 0.29] for predictive designs, respectively. An omnibus test indicated that the small descriptive difference between effect sizes between the applicant and incumbent samples was not significant, F (1, 100) = .97, p = .33.

3.2.3 Sample type × study design

Ultimately, we tested the interaction of sample type and study design to investigate one of the main questions of this study: do estimates of validity generalize to predictive studies with applicant samples, as are encountered in real-life selection procedures? Thereto, we performed a moderator analysis with three groups: concurrent/incumbent, predictive/incumbent, and predictive/applicant. The effect sizes were = .18 [.04, 0.31] for concurrent designs with incumbents, = .14 [−.01, .29] for predictive designs with incumbents and = .16 [.01, .31] for predictive designs with applicants, respectively. An omnibus test again indicated no significant differences between the groups, F (2, 98) = .58, p = .56.

4 DISCUSSION

The current study reviewed the prevalence of key design and sample characteristics of studies investigating the validity of self-report measures of conscientiousness to predict job performance and to quantify their impact on the validity estimates. Overall, the correlation of conscientiousness with job performance was in line with previously reported estimates (e.g., He et al., 2019) and moderator analyses did not reveal differences across types of samples (incumbent vs. applicant) or validation designs (concurrent vs. predictive). However, the overwhelming majority of research is conducted in concurrent designs with job incumbents. Only 12% of the studies published in the last 40 years investigated job applicants in predictive designs. Thus, common research practice is at odds with requests to conduct research with samples that match the population to which results should apply (Morgeson et al., 2007b). We, therefore, caution against interpreting the present findings lightheartedly - based on available evidence, questions concerning the predictive validity of self-report questionnaires of conscientiousness cannot be answered reliably. Therefore, it remains an open question whether or not self-report measures of personality retain their predictive validity in applied settings that entail faked responses. In the following, we discuss our concerns regarding faking in high-stakes personality testing, suggest a stronger emphasis on incremental predictive validity, and propose guidelines for future research.

4.1 Faking as key issue in validity of self-reports

At first sight, the present results are encouraging. Contrary to formerly raised concerns (e.g., Van Iddekinge & Ployhart, 2008), the validity of self-report measures of conscientiousness to predict job performance does not seem to differ meaningfully in applicant versus incumbent samples or concurrent versus predictive validation designs. Yet, these results need to be reconciled with the extensive evidence that applicants do fake to a substantial degree (Griffith & Converse, 2011), that individuals differ in the extent they are willing and able to fake successfully (e.g., Geiger et al., 2018, 2021; Kleinmann et al., 2011; Pavlov et al., 2018) and that, as a consequence, faking substantially alters the rank order of participants (e.g., Griffith et al., 2007; Krammer, 2020). Changes in rank orders imply that the personality constructs assessed via self-report measures are not measuring the same underlying disposition and are not measurement invariant between honest and faking conditions (e.g., Krammer et al., 2017). This affects the construct validity of personality tests—what is measured under faking might differ fundamentally compared to the construct measured under honest conditions. We acknowledge that the amount of faking observed in applied contexts is likely lower or more subtle than in laboratory studies (Birkeland et al., 2006; Hu & Connelly, 2021), but it would be naive to assume that faking is not highly prevalent, particularly in high-stakes contexts with well-educated and prepared applicants.

The variance captured by faked self-report measures of personality still predicts job performance, but we question if that is still predominantly the same variance captured in low-stakes settings. Recent research suggests that faked personality scores reflect individual differences in the ability to fake successfully (i.e., achieve high scores in relevant personality traits) to some degree, which has been explained with the ability to identify criteria, i.e., the ability to identify the targeted selection criteria (e.g., Klehe et al., 2012). The ability to fake successfully has been linked to individual differences in fluid intelligence, crystallized intelligence, and interpersonal abilities (Geiger et al., 2018, 2021). Critically, all these abilities are correlated with job performance (Schmidt & Hunter, 1998). This perspective would reconcile findings that faking fundamentally affects self-report measures of personality but doesn't invariably lead to decrements in criterion validity.

While faking seems to be ignored or deemed irrelevant in validation studies, there is a vast body of research that illustrates its prevalence and investigates methods to prevent it (Ziegler et al., 2011). Among them, the forced-choice (FC) format enjoys continued popularity due to its presumed resistance against faking. Yet, we decided to omit forced-choice measures from the current review. We did so because FC response formats function fundamentally differently than the widely applied single stimulus (e.g., Likert) measures. Due to their relative nature, conventionally scored FC measures result in (quasi-) ipsative scores which prohibit interindividual comparisons (Brown et al., 2013; Hicks, 1970). There is an ongoing controversy and active research on how to best construct FC measures (e.g., Watrin et al., 2019), how to make FC measures faking resistant (e.g., Pavlov et al., 2021) and under which conditions scores from FC measures are valid (e.g., Bürkner, 2022). Taken together, FC format might have the potential to reduce detrimental effects of faking. However, a cascade of questions concerning the validity of FC personality tests in general and in the selection more specifically should be studied in a separate meta-analysis first.

4.2 Call for a stronger focus on incremental validity

Because faked personality scores might capture variance other than honest personality, it is crucial to investigate the validity jointly with competing constructs to obtain meaningful estimates of predictive and, more importantly, incremental predictive validity. Personnel selection is rarely based on a single source of information. Instead, the aim is to obtain relevant and complementary pieces of valid information about the applicant and to combine this information in a way that maximizes the probability of valid inferences about future job performance. Comprehensive meta-analyses provide evidence on which dispositions are suitable for this purpose - first and foremost tests of cognitive abilities (e.g., Schmidt & Hunter, 1998). Conscientiousness has been shown to provide a small but significant amount of incremental validity above cognitive ability (Schmidt & Hunter, 1998). However, this estimate hinges upon the low correlation of conscientiousness and cognitive ability, which was estimated in samples where faking was unlikely to be an issue (e.g., Judge & Jackson, Shaw, et al., 2007; Table 3). Given the recent evidence that conscientiousness and cognitive ability are more strongly correlated under faking (Schilling et al., 2020), and that the construct validity of self-report measures of conscientiousness are potentially affected by faking, we need improved meta-analytic estimates of the correlation of both constructs and estimates of incremental validity under faking. However, this would presuppose enough primary studies in which both conscientiousness and cognitive ability were measured in high-stakes settings with applicants in predictive designs. Such studies would be a subset of all predictive studies with applicants, but none was present in our review, which shows a clear need for research.

4.3 Limitations and future directions

The generalizability of the current results is limited due to the small number of studies with real applicants and predictive validation designs. Either such studies are rarely conducted, or their results are not being published. The former is not very likely given the prominence of conscientiousness in I&O psychological research and the ease with which such questionnaires can be applied in a wider variety of personnel selection settings. Companies offering personality tests for personnel selection can pursue a number of incentives by virtue of gathering evidence in support of their products. It is therefore likely, that either publishing results does not rank highly in all companies' reward agenda or results are actively withheld from going public. Personal communications with practitioners and anecdotal reports, such as in Van Iddekinge et al. (2012), suggest that the latter is certainly prevalent. As a consequence, there is reason for concern that unpublished results would depress the validity of the results collected here.

Given the far-reaching personal and economic consequences of personnel selection decisions, we call for more publications on the validity of self-report measures of personality under realistic conditions. Such publications should meet several criteria. First, they should comprise real job applicants who respond to personality tests in a high-stakes situation. Second, job performance of recruited applicants should be evaluated at a later stage based on sufficient valid performance data. Third, preferably personality and performance data should also be gathered from job incumbents. Using a matching procedure—as proposed by Jeong et al. (2017), for example—allows to compare validity estimates for applicants and incumbents. Fourth, available additional measures should be included for evaluating incremental validity. Fifth, commitments to quality standards for ensuring study quality should be default in such studies (e.g., DIN33430; ISO10667). Additionally, validation studies should be preregistered. In all likelihood, just like in other disciplines in (e.g., see Dechartres et al., 2016; for the systematic influence of mandatory preregistration on results in medicine) a bias of results in studies with conflicts of interests is to be expected. Sixth, such publications should adhere to open sciences practices. Sophisticated methods of de-identification and synthetic data procedures have been proposed that address legitimate privacy concerns while ensuring the ability to verify results (Grund et al., 2022; Walsh et al., 2018). If more studies meeting these requirements were available, a more dependable verdict concerning the predictive validity of self-report measures of personality and its moderators were possible.

5 CONCLUSION

In sum, the current meta-analysis leaves us with an ambivalent view on the predictive validity of self-reported measures of conscientiousness. On the one hand, validity estimates were comparable between presumably low-stakes and high-stakes settings. On the other hand, their magnitude must still be considered low (Morgeson et al., 2007a) and the number of studies comprising real job applicants and predictive validation designs is frustratingly low. Research is predominantly conducted in settings that do not allow investigating the greatest threat to predictive validity: faking. Thus, the present results are preliminary and call for more multivariate studies including competing methods of selection in real high-stakes personnel selection processes to answer two important questions: how and to which degree does faking affect the predictive validity of self-report measures of personality in applied contexts and, more importantly, how does faking affect the incremental validity above and beyond established ability constructs with significantly higher criterion-related validity?

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency. We thank Anna Kaisinger, Raimund Krämer, Natasa Subotin, and Tim Trautwein for their help with coding studies and Sally Olderbak for her methodological advice. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ENDNOTE

APPENDIX A:

Table A1.

| Conscientiousness | AND | Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Personality, Five-factor model, 5-factor model, FFM, Big5, Big Five | Job Performance, | |

| Conscientiousness | Work Performance, | |

| Orderliness, Order, Organization, Task planning, Planfulness, Tidiness, Cleanliness, Neatness, Punctuality, Perfectionism, Diligence, Meticulousness, Methodicalness, Superficiality, Discipline, Formalness, Conventionality, Traditionalism | Performance Rating, | |

| Industriousness, Achievement-Striving, Achievement Motivation, Achievement, Action Orientation, Activity, Autonomy, Competence, Decisiveness, Endurance, Efficiency, Goal-Striving, Initiative, Laziness, Perseverance, Persistence, Procrastination, Purposefulness, Rationality, Self-Efficiency | Overall Performance | |

| Self-Control, Careless, Cautiousness,a Control, Constraint, Deliberation, Impulse Control, Impulsivity, Impulsiveness, Self-Discipline | ||

| Responsibility, Caution,a Compliance, Dutifulness, Dependability, Prudence, Reliability |

- Note: Detailed search strings for the respective databases are provided in OS1.

- a This duplication did not affect the present results because none of the constructs in the primary studies were coded as “Cautiousness” or “Caution.”

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in OSF at https://osf.io/87gyr/