Evaluation of the Post Stroke Checklist: a pilot study in the United Kingdom and Singapore

Abstract

Background

There is currently no standardized process for long-term follow-up care. As a result, management of poststroke care varies greatly, and the needs of stroke survivors are not fully addressed. The Post Stroke Checklist was developed by the Global Stroke Community Advisory Panel as a means of standardizing long-term stroke care. Since its development, the Post Stroke Checklist has gained international recognition from various stroke networks and is endorsed by the World Stroke Organization to support improved stroke survivor follow-up and care.

Aims

The aim of this study was to evaluate the feasibility and usefulness of the Post Stroke Checklist in clinical practice and assess its relevance to stroke survivors in pilot studies in the United Kingdom and Singapore.

Methods

The Post Stroke Checklist was administered to stroke survivors in the United Kingdom (n = 42) and Singapore (n = 100) by clinicians. To assess the feasibility of the Post Stroke Checklist in clinical practice, an independent researcher observed the assessment and made notes relating to the patient–clinician interaction and their interpretations of the Post Stroke Checklist items. Patient and clinician satisfaction with the Post Stroke Checklist was assessed by three questions, responded to on a 0–10 numerical rating scale. Clinicians also completed a Pragmatic Face and Content Validity test to evaluate their overall impressions of the Post Stroke Checklist. In the United Kingdom, a subset of patients (n = 14) took part in a concept elicitation interview prior to being administered the Post Stroke Checklist, followed by a cognitive debriefing interview to assess relevance and comprehension of the Post Stroke Checklist.

Results

The Post Stroke Checklist identified frequently reported problems for stroke survivors including cognition (reported by 47·2% of patients), mood (43·7%), and life after stroke (38%). An average of 3·2 problems per patient was identified across both countries (range 0–10). An average of 5 and 2·6 problems per patient were identified in the United Kingdom and Singapore, respectively. The average time taken to administer the Post Stroke Checklist was 17 mins (standard deviation 7·5) in Singapore and 13 mins (standard deviation 7·6) in the United Kingdom. Satisfaction ratings were high for patients (8·6/10) and clinicians (7·7/10), and clinician feedback via the Pragmatic Face and Content Validity test indicated that the Post Stroke Checklist is ‘useful’, ‘informative’, and ‘exhaustive’. All concepts measured by the Post Stroke Checklist were spontaneously discussed by patients during the concept elicitation interviews, suggesting that the Post Stroke Checklist is relevant to stroke survivors. Cognitive debriefing data indicated that the items were generally well understood and relevant to stroke. Minor revisions were made to the Post Stroke Checklist based on patient feedback.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that the Post Stroke Checklist is a feasible and useful measure for identifying long term stroke care needs in a clinical practice setting. Pilot testing indicated that the Post Stroke Checklist is able to identify a wide range of unmet needs, and patient and clinician feedback indicated a high level of satisfaction with the Post Stroke Checklist assessment. The items were generally well understood and considered relevant to stroke survivors, indicating the Post Stroke Checklist is a feasible, useful, and relevant measure of poststroke care.

Introduction

The World Health Organization estimated that 15 million people worldwide experience a stroke every year 1. Of these, a third are left permanently disabled, impacting the patient's quality of life, as well as placing burdens on family, health systems, and the wider community 1.

Following a stroke, patients can experience various long term problems such as memory loss 2, spasticity 3, urinary incontinence 4, pain 5, and cognitive impairment 6. These problems can result in a significant impact on the lives of patients and contribute to an overall decrease in quality of life among many patients, impacting their social relationships, emotional well-being, physical functioning, and independence 7, 8. A long-term study conducted by Feigin et al. demonstrated that at five-years post stroke, 29·3% of patients experienced depression, 22·5% had dementia, 15% had been institutionalized, and 20% had experienced a recurrent stroke 9.

Despite the existence of national stroke strategies and guidelines for the management of post-stroke care [e.g. UK National Stroke Strategy 10, NICE guideline 11, Singapore Ministry of Health Stroke Clinical Practice guidelines 12 ], there is currently no standardized process for long-term follow-up care. As a result, knowledge and management of long-term poststroke care varies greatly between clinicians 8 and national healthcare systems 13, and the needs of patients are not fully addressed. For example, a UK study reported that 49% of patients had needs not addressed by healthcare providers, such as emotional problems, fatigue, difficulties concentrating, and memory problems 14.

To address this gap, the Global Stroke Community Advisory Panel (GSCAP), an international, multidisciplinary group of stroke experts, developed the Post Stroke Checklist (PSC) (Fig. 1) to help clinicians standardize the process of identifying long-term problems and making appropriate treatment referrals 15. Adopting a Delphi process, GSCAP identified key long-term problem areas for stroke patients and reached a consensus on which areas had the greatest impact on patients’ quality of life and could be addressed by evidence-based interventions. Eleven poststroke problem areas were rated highly relevant to include in the PSC: secondary prevention, activities of daily living (ADLs), mobility, spasticity, pain, incontinence, communication, mood, cognition, life after stroke, and relationship with caregiver 15. The PSC has gained international recognition from various stoke networks and advocacy groups and is endorsed by the World Stroke Organization to support improved stroke survivor follow-up and care 16.

Post Stroke Checklist (PSC).

Aims

The aim of this study was to evaluate the feasibility and usefulness of the PSC in clinical practice and assess its relevance to stroke survivors in two parallel PSC pilot studies in the United Kingdom and Singapore.

Methods

Instrument

The PSC 15 is an 11-item checklist, administered by a clinician to poststroke patients. Each item comprises a dichotomous ‘yes’/‘no’ response scale and provides referral recommendations for each problem identified.

Sample

Pilot studies were conducted in the United Kingdom and in Singapore between January 2012 and May 2013. In the United Kingdom, participants were recruited from primary care practices and a hospital stroke rehabilitation outpatient unit in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire. In Singapore, patients were recruited from the Cognitive Outcomes After Stroke study, an ongoing investigation of 400 stroke patients identified from the acute stroke service 17. Clinicians at each site were invited to participate in administrating the PSC to test its feasibility and usefulness across various professions. A range of clinicians from various backgrounds were targeted. Ethical approval was obtained from the National Research Ethics Committee in the United Kingdom and from the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board in Singapore. Patients were eligible to participate if they had experienced a cerebral infarction or intracerebral hemorrhage between 8 and 60 months ago (for UK patients) and between 9 and 36 months ago (for Singapore patients). Expressive dysphasic patients were included, provided they were able to respond to the PSC items.

Procedure

The study was conducted in general practice clinics and a hospital stroke unit in the United Kingdom and in a research facility in Singapore. Prior to completing the PSC with patients, a researcher provided training to the clinicians demonstrating how the PSC should be administered.

Evaluation of the PSC involved a clinician administering the checklist to patients on a one-to-one basis. During administration of the PSC to all patients in the United Kingdom and English-speaking patients in Singapore, a trained researcher was present in the room, as an observer, to note any issues with the checklist administration and record the duration of the assessment visit and the time taken to administer the checklist. Following completion of the PSC, each patient completed a satisfaction questionnaire. Clinicians also completed a satisfaction questionnaire following each assessment. At the end of each pilot, clinicians also completed a Pragmatic Face and Content Validity test (PRAC-Test) 18 to evaluate their overall impressions of the PSC.

In the United Kingdom, qualitative, face-to-face interviews were also conducted with 14 patients. The interview was divided into two segments: a 35-mins concept elicitation interview, to explore the impact of stroke on patients’ lives (this was conducted immediately prior to PSC administration) and a 45-mins cognitive debriefing interview [a qualitative research tool used to determine whether concepts and items are understood by patients in the same way that instrument developers intend 19 ] to explore the comprehensibility and relevance of PSC items to patients (this was conducted immediately following PSC administration).

Research outcomes

Feasibility of PSC administration in clinical practice

The feasibility of the PSC was assessed quantitatively by examining the time taken to complete the checklist and the frequency distribution of responses.

Patient comprehension and relevance of the PSC (face and content validity)

Comprehension of the PSC was assessed qualitatively in terms of the consistency of interpretations of each item between clinicians and patients and any issues noted with the PSC, identified through observer notes and the cognitive debriefing interviews. The relevance of the PSC was assessed from data collected during concept elicitation and cognitive debriefing interviews.

Satisfaction with the PSC

Satisfaction was assessed by clinician-completed and patient-completed satisfaction questionnaires, which asked participants to rate their satisfaction with the checklist across three items, each measured on a 0–10 numerical rating scale. Specifically, satisfaction was rated in terms of satisfaction with the PSC assessment, the ability of the PSC to correctly identify patient's needs, the perceived likelihood of receiving the required health care services (for patients only), and how helpful the PSC was in determining referrals (for clinicians only). Clinicians also completed the PRAC-Test at the end of the study to assess their overall views about the PSC.

Amendments to the PSC

All data collected during the pilots were used to update the PSC content, wording and format. This information will also be used to aid the development of a patient-completed version of the PSC.

Analysis

Quantitative data collected from the PSC, the patient and clinician satisfaction questionnaires, and PRAC test were summarized using descriptive statistics. Interview transcripts were analyzed in qualitative analysis software Atlas Ti (Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany), using thematic analysis techniques 20.

Results

Sample characteristics

Demographic and clinical information pertaining to the patient sample are presented in Table 1. The average age of patients was 63 years [standard deviation (SD) 11·2; range 24–95 years]. The majority of patients were male (72·5%), and most suffered from at least one comorbidity, with cardiovascular disease the most frequently reported (78%).

| Patient characteristics | Singapore (n = 100), n (%) | UK (n = 42), n (%) | Total (n = 142), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of patient | |||

| Mean (SD) | 61 (10·9) | 72 (8·1) | 63 (11·2) |

| Min–Max | 24–95 | 46–86 | 24–95 |

| Missing/No response | 1 (1) | 3 (7·3) | 4 (2·8) |

| Patient gender | |||

| Male | 75 (75) | 23 (54·8) | 98 (69) |

| Female | 25 (25) | 17 (40·5) | 42 (29·6) |

| Missing/No response | 0 (0) | 2 (4·8) | 2 (1·4) |

| Time since most recent stroke (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1·1 (0·4) | 1·7 (0·7) | 1·3 (0·6) |

| Min–Max | 0–2·9 | 0·4–3·3 | 0·0–3·3 |

| Missing/No response | 9 (9) | 7 (16·7) | 16 (11·3) |

| Current poststroke treatment* | |||

| Antiplatelet | 81 (81) | 13 (31) | 94 (66·2) |

| Anticholesterol | 36 (36) | 18 (42·9) | 54 (38) |

| Anticoagulant | 6 (6) | 5 (11·9) | 11 (7·7) |

| Antihypertensive | 38 (38) | 17 (40·5) | 55 (38·7) |

| Antihyperglycemic | 18 (18) | 1 (2·4) | 19 (13·4) |

| Physical therapy | 0 (0) | 5 (11·9) | 5 (3·5) |

| Occupational therapy | 0 (0) | 1 (2·4) | 1 (0·7) |

| Speech and language therapy | 0 (0) | 1 (2·4) | 1 (0·7) |

| Psychological therapy | 0 (0) | 3 (7·1) | 3 (2·1) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 2 (4·8) | 2 (1·4) |

| Missing data/No treatment | 15 (15) | 4 (9·5) | 19 (13·4) |

- *The type of stroke experienced by patients was not recorded.

The UK pilot involved three practice nurses, two research nurses, two general practitioners, one occupational therapist and a stroke consultant. The Singapore pilot involved five research coordinators, two research fellows, two stroke specialists and a research rater.

Feasibility of the PSC

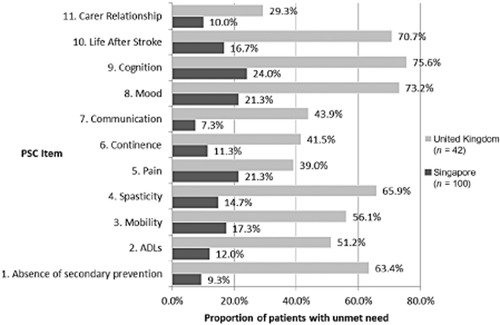

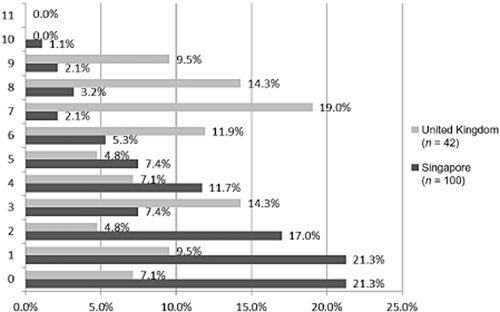

The PSC identified a wide range of unmet needs (Fig. 2). The most frequently reported problem for patients was cognition, reported by 47·2% of patients. Mood was also frequently reported (43·7%), as was life after stroke (38%). Relationship with caregiver was the least frequently reported problem, reported by 19% of patients. The needs identified by the PSC were consistent across both countries. An average of 3·2 problems per patient was identified across both countries (range 0–10). An average of 5 and 2·6 problems per patient were identified in the United Kingdom and Singapore, respectively (Fig. 3). The average time taken to administer the PSC was 17 mins (SD 7·8) in Singapore and 13 mins (SD 7·6) in the United Kingdom.

Unmet needs identified with the Post Stroke Checklist.

Number of referrals received per patient.

Patient comprehension and relevance of the PSC (face and content validity)

Observation of the PSC assessment indicated that the PSC items were generally well understood by patients when read aloud to them by the clinician. The cognitive debriefing interviews indicated that patients generally understood and interpreted the items as intended. In addition, the data indicated that the PSC items were mostly relevant to patients, with most patients reporting that they currently experience or have recently experienced the impacts measured.

Most patients appeared to be using the correct recall period of ‘since your stroke or last assessment’ when answering the questions.

Some patients attended the assessment with a family member or carer, who also helped the patient respond to the PSC items. In some of these cases, the carer interpreted the item in a different manner to the patient, or disagreed with the patient's response and encouraged them to change their answer. In these instances, the clinician marked down the patient's final answer.

Observations of the PSC administration also indicated that the items were interpreted consistently between clinicians. In some instances, there was discordance between the clinicians’ and the patients’ interpretation of certain items. This was particularly the case for item 1 (‘Since your stroke or last assessment, have you seen anyone regarding reducing the risk of another stroke?’), where patients focused on appointments made specifically to receive advice, whereas clinicians encouraged patients to think about regular check-ups such as blood pressure and cholesterol checks. In most cases, the patient changed their response when the clinician clarified their interpretation of the item.

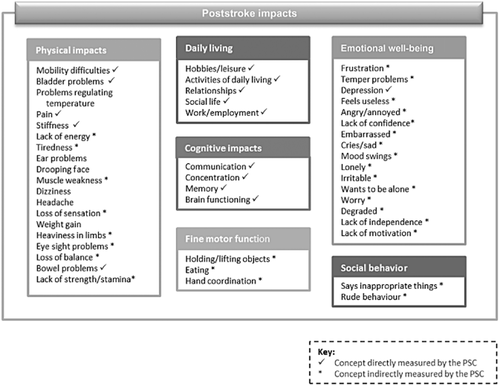

Patients spontaneously reported several symptoms and impacts on different areas of daily life during the concept elicitation interviews. The impacts discussed varied greatly between patients. Frequently discussed post-stroke problems included physical impacts, such as mobility (n = 10) and pain (n = 9); impacts on ADLs, such as preparing meals (n = 8) and housework (n = 6); and the emotional impact, for instance feeling frustrated, which appeared to be primarily related to a lack of independence, and the inability to carry out daily tasks as achieved prior to the stroke. All 10 symptom concepts assessed in the PSC were spontaneously discussed by patients in the concept elicitation interviews.

During concept elicitation, some concepts were mentioned by patients that are not directly assessed in the PSC, including muscle weakness, fatigue, loss of sensation, fine motor function, and social behavior (see Fig. 4 for a comparison of the concepts elicited in qualitative interviews, with those assessed in the PSC). Despite not being directly measured, observation of the PSC administration indicated that such concepts still arose when the clinician went through the 11 PSC items with the patients, suggesting that these are indirectly measured by the current PSC items. Other concepts reported that are not currently measured in the PSC included headache, dizziness, and weight gain, although these were reported by just one patient each, suggesting they may not be representative of the symptoms experienced by most stroke survivors.

Conceptual model of poststroke impacts.

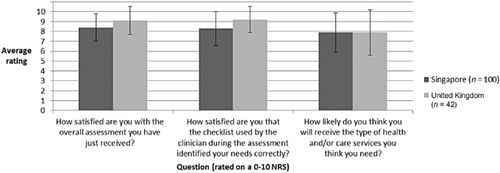

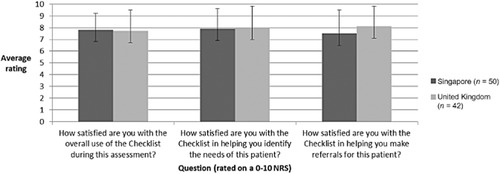

Satisfaction with the PSC

Patient satisfaction with the PSC assessment was high, with an average rating of 8·6/10. Patient ratings of satisfaction that the PSC identified their needs was also high; however, the data indicated that patients believe they are not so likely to receive the health and/or care needed (Fig. 5). Clinician satisfaction with the PSC varied greatly between the patients they assessed; however, satisfaction was generally high (Fig. 6). This suggests that the variability of clinician satisfaction between patients is due to how the PSC performs with individual patients rather than due to individual clinicians.

Patient satisfaction with the Post Stroke Checklist.

Clinician satisfaction with the Post Stroke Checklist.

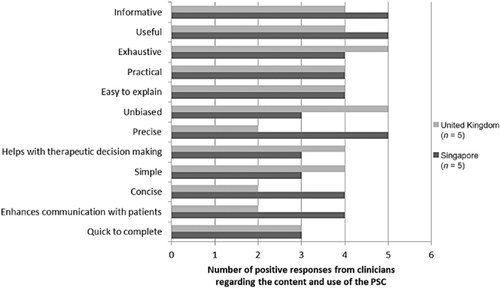

In terms of clinician's overall views of the PSC, their feedback regarding the content and ease of use of the PSC (as measured with the PRAC-Test) was generally positive, with most clinicians indicating that the PSC is ‘useful’, ‘informative’, and ‘exhaustive’ (Fig. 7). These terms were endorsed by 9/10 clinicians, whereas 8/10 agreed that the PSC is ‘easy to explain’, ‘practical’, and ‘unbiased’.

Clinicians’ views of the Post Stroke Checklist.

Amendments to the PSC

The pilot studies identified some areas of improvement for the PSC items. With this in mind, some items were reworded based on the concepts discussed and language used by patients during the qualitative interviews and the observed PSC administrations.

For item 1 (‘Secondary Prevention’), there was inconsistency between the patients’ interpretation of what constitutes ‘reducing the risk of another stroke’; based on the observations for the PSC administration and feedback during the cognitive debriefing interviews, this was changed to ‘advice on changes to lifestyle or medications for preventing another stroke’. For item 11 (‘Relationship with Caregiver’), one patient in Singapore misunderstood the term caregiver to mean his doctor. In the United Kingdom, patients commented that this item was not relevant as they did not consider themselves to have a caregiver. With this in mind, the term ‘caregiver’ was reworded to ‘family’. These changes were tested in 50/100 patients in Singapore, and the revised items were well understood.

Discussion

The findings suggest that the PSC is a feasible and useful measure for identifying long-term stroke care needs in a clinical practice setting. Pilot testing indicated that the PSC is able to identify a wide range of unmet needs; with cognition, mood, and life after stroke being the most frequently identified issues for stroke survivors. Patient and clinician feedback indicated a high level of satisfaction with the PSC assessment and its ability to correctly identify their needs, though patients were slightly less confident that they would receive the required services to target such needs. Qualitative interviews with stroke patients, and observations of the PSC assessment indicated that the PSC was generally well understood by patients and considered relevant to their needs, thus demonstrating face and content validity. Although there were some issues with items 1 and 11, these seemed to be a result of inconsistent interpretation between patients, as opposed to a lack of understanding. Minor rewording of the two items appeared to resolve these issues; testing of the revised measure in Singapore elicited a more consistent understanding across the sample.

Qualitative interviews with post-stroke patients identified some concepts not currently measured by the PSC, including fatigue, muscle weakness, fine motor function, and social behavior. The GSCAP members discussed potential item additions, although given the purpose of the PSC is to be a concise referral tool, which is both quick and easy to administer, the decision was made to not add more items. This was primarily driven by two factors: first, some concepts are not easily resolved by community referrals, for instance fatigue. Second, observation of the PSC administration indicated that the majority of additional concepts discussed by patients are indirectly assessed by the current PSC items; thus, it was felt that increasing the length of the PSC would not be beneficial to patients or clinicians.

The mixed methods design utilized in this research has provided a comprehensive overview of the feasibility and usefulness of the PSC in identifying poststroke needs. The authors recognize that the sample size utilized in this study, though appropriate for the study purposes, is not sufficient to invite cross-country comparisons. It is anticipated that these findings will spur the implementation of the PSC into larger stroke research studies globally, which will allow such conclusions to be made.

One limitation of this research is that qualitative feedback was obtained in the United Kingdom only and thus may not be entirely representative of stroke survivors internationally. Qualitative work (in particular cognitive debriefing interviews) in additional countries, including Singapore, might strengthen the evidence of the face and content validity of the PSC. In addition, the Singapore pilot stipulated that patients must have experienced a stroke within 9–60 months of the study, compared with 8–36 months for the UK pilot. The broader time permitted for the Singapore pilot may have resulted in a more varied sample, in terms of the symptoms and impacts experienced, and the severity of such symptoms, which may have in turn influenced satisfaction and PSC responses. However, it was felt that although different, the time stipulated in both pilots was acceptable enough to allow recruitment of a range of patients. For this pilot study, data regarding stroke severity and lesion volume was not collected. Further research may provide beneficial insights regarding whether baseline factors such as stroke severity as measured by the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale or lesion volume affects the feasibility and usefulness of the PSC.

Presently, one of the limitations of the PSC is the time taken to complete the assessment. Pilot testing indicated that the PSC took, on average, longer to complete than a regular 10–15 mins consultation. This therefore suggests that, at present, it may not be possible to complete the full assessment within a regular consultation. Clinicians should consider this factor when scheduling post-stroke assessments and consider booking an extended appointment, particularly if they are not familiar with the PSC. It is, however, expected that with practice, clinicians will become familiar with the items and the referrals, thus decreasing the time needed for the PSC assessment over time. Moreover, patient-completed version of the PSC is currently being developed. This may be a useful alternative that can be completed prior to arriving at the doctor's office, or for patients who have difficulties travelling to see their doctor in order to be assessed by the current clinician-completed version.

Another limitation of the PSC is that it can only provide recommendations for treatment or further care; it is not capable of enforcing follow-up care, and so it is up to the clinician to ensure these are carried out. In addition, it is not yet known how different healthcare systems will impact the implementation of the PSC referrals; for instance, referrals may be more accessible to patients in countries such as the United Kingdom and Canada, where health care is free of charge, as opposed to countries where health care is paid for privately by the patient. Work is currently ongoing in the United Kingdom and Singapore to assess the outcomes of the PSC assessment. Patient satisfaction with the referrals made from the PSC is being evaluated, as well as the impact of the referrals on patient's quality of life, and their perceived level of needs.

The PSC is currently being further implemented in various practices across the United Kingdom, Singapore, United States, and Canada, based on preliminary pilot results and several physician endorsements. It is hoped that the results of this study will further encourage the implementation of the PSC globally, to allow standardized strategies for stroke care to be implemented across various healthcare systems to ultimately improve the lives of stroke patients.