Weight management counselling among community pharmacists: a scoping review

Abstract

Objectives

To complete a scoping review of studies of community pharmacy-delivered weight and obesity management services from January 2010 to March 2017.

Methods

A scoping review was conducted to obtain an overview of research related to the study objective. The PubMed, EBSCO and CINAHL databases were searched from January 2010 to March 2017 for articles examining obesity/weight management in community pharmacies. Included studies had to contain an obesity/weight management programme delivered primarily by community pharmacies. All non-interventional studies were excluded.

Key findings

Nine articles were eligible for data extraction. Across the nine included studies, 2141 patients were enrolled. The overwhelming majority of patients enrolled in the studies were female, approximately 50 years of age, had a mean weight of 92.8 kg and mean BMI of 33.8 kg/m2 at baseline. Patients in these various programmes lost a mean of 3.8 kg, however, two studies demonstrated that long-term (>6 months) weight loss maintenance was not achieved. The average dropout rate for each study ranged from 8.3% to 79%.

Conclusions

Obesity has a significant impact on the health and wellness of adults globally. Recent research has shown that community pharmacies have the potential to positively impact patient weight loss. However, additional research is needed into the specific interventions that bring the most value to patients and can be sustained and spread across community pharmacy practice.

Introduction

Obesity continues to be a major health concern throughout the world. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), overweight and obesity are defined as an excessive accumulation of fat designated by body mass index values ≥25 (overweight), or ≥30 (obesity).1 Rates of obesity have more than doubled since 1980, with roughly 600 000 million people worldwide having obesity in 2014.1 In the United States, it is estimated that more than 70% of the population is currently overweight, with roughly 40% of this group falling into either the obese or extremely obese categories.2 In Canada, more than 20% of the population is classified as obese, with an additional 34% being overweight.3 In the United Kingdom (UK), roughly 61–63% of the population is overweight or obese. Of that 61–63% of the population, between 25% and 27% are classified as obese.4, 5 Moreover, obesity is no longer just a concern for Western nations, as countries like India and China are also facing increasing rates of obesity.6 According to the WHO, most of the world's population now live in countries where overweight and obesity kills more people than underweight.1

Obesity is the most common preventable risk factor for high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory diseases and cancer.7 A recent umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses found that there was strong evidence linking excess body weight with 11 different cancers, including both colon and breast cancers.8 However, heart disease remains one of the top two leading causes of death in many Western nations,9, 10 and the prevalence of diabetes continues to increase.11 As such, finding alternative approaches to help people more successfully manage their weight is crucial. An important step in this process took place in 2013 when the American Medical Association officially labelled obesity a disease with multiple risk factors, requiring a range of treatment interventions.12

This disease also places significant financial strain on countries’ healthcare systems. For example, obesity-related healthcare services were estimated to cost between $147 and $210 billion per year in the United States.13 By 2008, half of these costs were being incurred by federal government spending through Medicaid and Medicare.14 On an individual level, it was estimated in 2008, that individuals with obesity had annual health care costs approximately $1400 higher than individuals of normal weight.1 In England, the costs of treating people with obesity have increased from £479.3 million in 1998 to £4.2 billion in 2007.5, 15 While more recent estimates are not available, given the continuing rise in rates of obesity, there is no reason to suspect that these figures have declined.

Pharmacists are widely regarded as being among the most trustworthy and accessible healthcare professionals.16 In the community setting, pharmacists are uniquely accessible to patients as demonstrated by a report of a study conducted in North Carolina, USA, wherein they found pharmacists interacted with patients up to 35 times per year, versus only 3.5 times for primary care providers.17 In addition, pharmacists have the opportunity to counsel patients during the medication dispensing process, a key point of access, especially in rural areas where limited availability of health services can compound typical barriers.18

There is increasing evidence illustrating that pharmacists’ management of chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidemia leads to clinically significant improvements in patients’ HbA1c, blood pressure and LDL-c levels.19-21 Pharmacists have also demonstrated the ability to help patients successfully address health issues related to behaviour changes such as tobacco cessation.22 Furthermore, economic analysis of pharmacists’ direct management of patients with a variety of health conditions are generally positive.23 Therefore, the research question driving this investigation is can community pharmacies assist patients in managing their weight?

Given these factors, community pharmacists are increasingly being asked to take on public health roles in disease prevention and management in conditions like obesity. A recent report by O'Neal identified a number of opportunities, including patient accessibility and ability to tailor education to patient needs, for pharmacists to begin providing weight management services.24 However, they also identified barriers for pharmacists, such as lack of training in obesity management.24 This research further described a number of previously conducted studies involving pharmacist-provided weight management services and showed modest weight reductions for study participants.24

Two other reviews noted similar findings, along with a number of methodological concerns, such as the lack of randomized control trials (RCT) and that few studies examined the relationship between sociodemographic/socio-economic factors and the ultimate effect of the intervention.22, 25 Furthermore, the majority of the studies identified in these reviews were conducted prior to 2010. Most importantly, the interventions developed in these previous studies were neither sustained in the participating pharmacies nor were they scalable to other community pharmacies. As such, the aim of this scoping review was to provide an updated review of the literature regarding community pharmacy weight management programmes since 2010 and determine if more recent studies have addressed these previous concerns.

Objective

To complete a scoping review of studies of community pharmacy-delivered weight and obesity management services from January 2010 to March 2017.

Methods

Study design

A scoping review was chosen to achieve the objective of this study. Scoping reviews involve a knowledge synthesis process whereby an exploratory question is used to guide a broad and inclusive literature search to identify gaps and develop alternative approaches for new research.26 The authors chose a scoping review to capture all previous research related to the provision of weight and obesity management services by community pharmacists. More quantitatively oriented systematic reviews would necessitate the exclusion of potentially important works due to the variety of methodological approaches, ranging from pre-/post-studies to RCT, used in much of community pharmacy practice research. Scoping reviews have been completed in a number of topic areas including pharmacists’ bias and pharmacists’ perceptions of success in practice.27, 28

There are six basic steps involved in the completion of a scoping review. The first is the identification of an appropriate research question, which was completed in the objective of this study. The second step is to develop a search strategy and undertake the search. Third is to select studies based on pre-identified inclusion criteria. Fourth is to extract the relevant data. Fifth is to analyse and display the data in meaningful themes. Sixth, and finally, is to provide a summary of the findings, along with relevant implications and directions for future research.26, 29 Steps two through four will be outlined in the remainder of the methods section. Steps five and six will be outlined in the results and discussion sections, respectively.

Search strategy

Active intervention, behaviour modification/cognitive behaviour modification, obesity prevention, obesity prevention programme, patient education, pharmacist counselling, self-regulation/self-management, weight control practices, weight gain prevention, weight loss, weight loss maintenance, weight loss programme, weight management strategies, young adults, pharmacist-assisted weight loss, dietary modification, exercise modification, peer support, group intervention, group education, community pharmacy/pharmacist, obesity management, obesity, obese, overweight, pharmacist interventions in weight loss, pharmacist, pharmacy education, pharmacy knowledge/information, pharmacy students, training programmes, weight management.

Study selection

Given the objective of this scoping review, to provide an overview of studies examining community pharmacy-delivered weight and obesity management services since January 2010, studies focusing only on pharmacists’ compensation for clinical services, wherein pharmacists acted as consultants, patient or other healthcare professional perspectives of pharmacist delivered weight management programmes, and pharmacist perceptions of weight management programmes were excluded.

Data extraction and analysis

The data extracted from the selected studies included study location, design, patient inclusion criteria and recruitment, details on the weight management programme, patient demographics and study outcomes. When possible, exact numerical values were taken from the included articles, however, the sample percentages for women and dropout rate percentages were calculated by hand using other data points.

Results

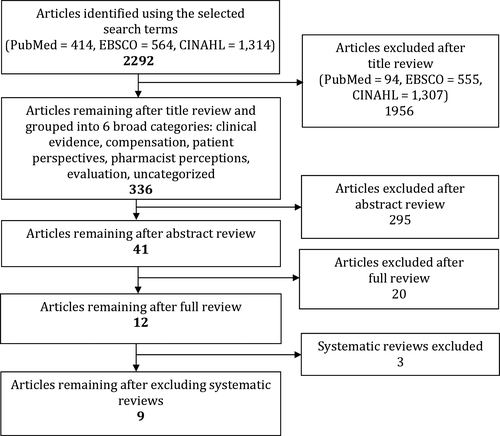

Of the 2292 articles, 336 initial articles were identified as relevant after a title review by authors JT, LW and MR. The remaining article abstracts were then reviewed by JT, LW and MR. This resulted in 41 articles remaining for full review. No non-English language articles were identified. The article selection flow diagram is outlined in Figure 1. After full review, an additional 29 articles were removed because they did not relate specifically to community pharmacy-delivered weight management services, and three additional articles were excluded because they were previously conducted systematic reviews. This decision was taken because the stated objectives of these reviews did not match the objective of this review. However, the reference lists of these excluded reviews were searched by hand to determine if any studies had been missed in the previous search. No new studies were identified through this process. This left nine studies remaining for data extraction and synthesis.

Study location and design

The included studies were conducted in various countries. Two studies were conducted in the United States,30, 31 three in England,32-34 two in Australia,35, 36 one in Scotland37 and one in Thailand.38 The study designs varied across all of the included studies. There were five pre-/post-studies,31, 32, 35, 37, 39 two RCTs,34, 38 one non-randomised retrospective comparison33 and one prospective cohort study.30

Patient inclusion criteria and recruitment

Eight of the studies targeted patients whose BMI ranged between 25 and 38.31-38 Four studies dictated that patients needed to be at least 18 years old.[32-34, 36] One study had an age range of 18–50 years,35 another's age range was 40–64 years37 and another's was 18–88 years.31 Three of the studies also targeted patients with obesity-related comorbidities (such as diabetes, hypertension or cardiovascular disease) or lowered the BMI requirement for those with comorbidities.33, 36, 37 Two studies targeted patients with risk factors for coronary heart disease,32 or chronic disease development.35 One study simply targeted patients who were interested in purchasing weight loss products.30 See Table 1 for complete details on patient inclusion criteria.

| Authors | Year | Patient inclusion criteria | Programme details | Programme length/frequency and follow-up (months/weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boardman | 2014 |

18 years of age 30–38 BMI Risk factor for coronary heart disease |

Advice on diet and exercise Individualized meal and exercise plans |

12 sessions spread over 6 months |

| Bush | 2014 |

18 years of age BMI of at least 30 BMI of at least 28 with obesity-related comorbidity |

My Choice Weight Management Programme Advice on diet, exercise, and behaviour change Food and exercise diary |

Weekly sessions for 12 weeks; follow-up at 2, 4, and 6 months after programme end |

| Harmon | 2013 |

18–88 years of age BMI < 30 or <27 and comorbidities aligned with indication for weight-loss pharmacotherapy |

Sessions were developed to follow ‘Take Care Health Systems weight management program’ Focus on selecting nutrient-dense food, different food groups, portion sizes, and healthy eating habits Focus on lifestyle change |

14 sessions (1 weekly for first month, 1 monthly for next 5 months) over 6 months |

| Jolly | 2011 |

18 years of age BMI of at least 30 |

Lighten Up Advice on diet, exercise, and behaviour change |

Weekly sessions for 12 weeks; follow-up at 1 year |

| Kellow | 2011 |

18–50 years of age Risk factor for chronic disease |

Waist Management Project Nutrition counselling from dietitian Advice on diet, exercise, and behaviour change Medication review from pharmacist Gym membership, cooking classes, supermarket tours, vegetable garden |

Monthly sessions for 12 months; measurements included those who stayed for at least 9 months |

| Morrison | 2013 |

40–64 years of age BMI of at least 30 BMI of at least 28 with obesity-related comorbidity |

Counterweight Programme Advice on diet Meal plan |

9 sessions spread over 12 months; specific sessions at 6, 9, and 12 months |

| Phimarn | 2013 | Overweight or obese diagnosis |

Advice on diet and exercise Food diary |

Sessions provided on weeks 0, 4, 8, and 16 |

| Um | 2015 |

18 years of age BMI of at least 25 Obesity-related comorbidity |

A Healthier Life Programme Advice on diet, exercise, and behaviour change |

6 sessions spread over 12 weeks |

| Wollner | 2010 | No criteria |

Advice on diet, exercise, and behaviour change Meal replacement and pharmacotherapy provided on as need basis |

Weekly sessions for 10 weeks |

Recruitment was typically done either by the pharmacy itself or by referral through a general practitioner or another healthcare provider. Five studies had pharmacists inquire about patients’ interest in participating based on certain indicators such as current weight loss therapies listed in patients’ medication profiles or expressed interest in weight loss products.30, 32, 33, 35, 36 Six studies had other healthcare professionals refer patients.32-35, 37, 38 Three studies had patients self-refer to the study through promotional materials displayed around the pharmacy or attached to recent prescriptions.31, 32, 36

Outline of weight management programmes

The main intervention of each programme was centred on behavioural counselling given to the patients, typically regarding diet, exercise and behaviour modification (see Table 1). Some of the more notable differences between interventions included additional nutrition counselling from a dietitian,35 as well as, meal replacement and adjunctive treatment with pharmacotherapy (as prescribed by the physician).30 The majority of the studies had only a pharmacist counselling the patients or administering the programme. Three studies had additional support from either general practitioners30, 33, 35 and/or dietitians.35 All study pharmacists received training specific to the study they were participating in, and the weight management programme they were administering. None appeared to have additional formal training in weight management. Study length ranged from 12 weeks33 to 12 months,35, 37 and patient follow-up visits varied for each study.

Enrolled patient demographics

Across all studies, there were a total of 2141 patients enrolled (with study sample sizes ranging from 1231 to 74034). The number of pharmacies involved in each study also varied. Four studies utilized one pharmacy to administer the programme.30, 31, 35, 38 Four studies utilized between 12 and 34 pharmacies.32, 33, 36, 37 One study did not specify how many pharmacies were involved in their study.34

The mean age of enrolled patients was 49.8 years (range of mean ages from 38.1–59.6 years); they had a means starting weight of 92.8 kg (range of means 66.8–110.7 kg) and a mean starting BMI of 33.8 kg/m2 (range of means 27.5–38.8 kg/m2). The lower values of 66.8 kg and 27.5 kg/m2 both came from the study conducted in Thailand.38 Additionally, women represented the majority of participants in all studies ranging from 62.5% to 85.6%. Upon programme conclusion, dropout rates varied greatly from 8.3% to 79%. See Table 2 for complete details.

| Primary authors | Patients enrolled | Per cent female % | # of Sites | Mean age (SD) | Mean starting weight in kg (SD) | Mean starting BMI in kg/m2 (SD) | Mean cumulative weight loss in kg or % if stated (per time point) | Dropout rate % (per time point) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boardman | 281 | 77 | 34 | 52.8 (38.4–67.2) | 96.3 (80.6–112.0) | 35.5 (31.4 to 40.6) |

−3.1 (3 months) −4.6 (6 months) |

−61.0 (2 months) −79.0 (6 months) |

| Bush | 451 | 85.6 | 12 | 41.1 (28.7–53.5) | 91.9 (73.4–110.4) | 34.5 (28.8 to 40.2) |

−2.4 (12 weeks) −3.4 (6 months after programme) |

−50.0 (12 weeks) −67.0 (6 months after programme) |

| Harmon | 12 | 83.3 | 1 | 51 (38–65) | 110.7 (75.9–142.3) | 38.8 (28 to 48.8) | −5 (6 months) | −8.3 (6 months) |

| Jolly | 740 | 72.9 | N/A | 48.9 (33.1–64.8)a | 92.8 (79.1–106.5)a | 33.4 (29.9 to 36.9)a |

−2.8 (12 weeks) −1.2 (1 year after programme) |

−15.7 (12 weeks) −41.0 (1 year) |

| Kellow | 40 | 62.5 | 1 | 38.1 (30.4–45.8) | 94.4 (77.6–111.2) | 33.5 (27.2 to 39.8) | −3.8 (9–12 months) | N/A |

| Morrison | 458 | 74.7 | 16 | 54.0 (46.6–61.4) | 96.4 (78.1–114.7) | 36.0 (30.1 to −41.9) |

−2.4 (3 months) −3.5 (6 months) −4.1 (12 months) |

−44.0 (3 months) −75.5 (12 months) |

| Phimarn | 75 | 80.3 | 1 | 59.6 (49.3–69.9) | 66.8 (59.4–74.2)b | 27.5 (24.3 to 30.6)b |

−1.8 (4 weeks) −1.8 (8 weeks) −0.8 (16 weeks) |

−1.3 (4 weeks) −10.7 (8 weeks) −12.0 (12 weeks) |

| Um | 34 | 71 | 8 | 50.7 (35.0–66.4) | 93.1 (76.0–110.2) | 34.3 (29.0 to 39.6) |

−0.6 (4 weeks) −2.0 (8 weeks) −3.5 (12 weeks) |

−35.0 (12 weeks) |

| Wollner | 100 | 84.9 | 1 | 51.6 | Not specified | 30.3 |

−1.6% (0–4 weeks) −6.0% (5–9 weeks) −8.1% (10 weeks) |

−30.0 (0–4 weeks) −60.0 (5–9 weeks) −74.0 (10 weeks) |

- aPharmacy group average was used; bExperimental group average was used.

Study outcomes

The majority of studies recorded weight loss in both kilograms and calculated as a percentage (see Table 2). The mean final visit weight loss for all studies that reported weight loss was 3.38 kg. However, several studies also reported intermediary weight loss numbers in an effort to account for participant dropout. One study only reported weight loss as percentage. This study reported an 8.1% mean weight loss at 10 weeks.30 Change in weight from baseline to final measure was statistically significant to the 0.05 level in all but one study, because participants in that study began to regain weight towards the end of the study period.38

Three studies compared pharmacy weight management programmes to the programmes run by other healthcare professionals.33, 34, 38 In the Bush et al.33 study, there was no significant difference in weight loss between the pharmacy and general practitioner programmes. The Jolly et al.34 study found that all weight loss programmes, including pharmacy intervention, achieved significant weight loss at the end of the programme. However, only the commercial programmes successfully maintained significant weight loss in participants 1 year after the programme ended.34 The Phimarn et al.38 study showed that pharmacist-only intervention was not significantly different from a group intervention.

Two studies completed post-study followed up with patients. The Bush et al.33 study did a 6-month post-study follow-up and found an average of 1 kg of additional weight loss after the study was completed. The Jolly et al.34 study did a 12-month post-study follow-up and found an average of 1.2 kg of sustained weight loss. However, statistically significant weight loss was not maintained in either of these studies.

Study evaluation

There are a number of important study design characteristics that must be considered in the evaluation of these studies. The most common limitation was the lack of a control group, given that only two of the included studies were RCTs (see Table 3).34, 38 Four studies had challenges with follow-up as the patient dropout range varied widely from 8.3% to 79% (see Table 2).30, 32, 33, 36 Four studies included some formal training of pharmacists in the administration of the weight management programme to patients.32, 34, 37, 39 Four studies were not generalizable to other patient populations or pharmacies because only one pharmacy was involved or the patient demographic characteristics were too narrow (ex. targeting patients with cardiovascular co-morbidities vs. enrolling any patient interested in weight loss).33, 35, 37, 38 Furthermore, the overwhelming majority of enrolled participants were women (see Table 2).

| Primary authors | Design | Control group (Y/N) | Pharmacist weight management training (Y/N) | Guideline based weight management programme |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boardman | Pre-/post-study | N | Y | Undetermined |

| Bush | Non-randomised, retrospective observation | N | Undetermined | Undetermined |

| Harmon | Pre-/post-study | N | N | 2010 Dietary Guidelines (USDA and HHS) |

| Jolly | RCT | Y | Y | Commercial programmes vs. NHS guided programmes |

| Kellow | Pre-/post-study | N | N | Undetermined |

| Morrison | Pre-/post-study | N | Y | NHS evaluated for primary care |

| Phimarn | RCT | Y | N | Undetermined |

| Um | Pre-/post-study | N | Y | National Health and Medical Research Council guidelines |

| Wollner | Prospective cohort | N | N | Undetermined |

Three studies contained some form of limited or inconsistent data collection. To minimize patient burden, one study varied patient follow-up for weight measurements (e.g. the 3-month weight measure could be taken anywhere from 6 to 15 weeks post-enrolment),34 another study failed to collect clinical and social factors that may have impacted weight loss37 and a final study used of non-validated nutrition history instruments.31 Finally, all of the studies used different weight management programmes, five of which could not be determined as emanating from previously established evidence-based weight management guidelines, making any comparison across studies difficult.30, 32, 33, 35, 38

Discussion

Across the nine studies in this scoping review examining community pharmacy-delivered weight management programmes, 2141 patients were enrolled. The majority of enrolled patients were women, approximately 50 years of age, had a mean starting weight of 92.8 kg and had a mean BMI of 33.8 kg/m2 at baseline. Patients in these various programmes lost a mean of 3.8 kg. Two studies also looked into and demonstrated that long-term (>6 months) weight loss maintenance was not achieved. An evaluation of the studies included in this scoping review revealed a number of potential limitations. To begin, only two of the studies were RCTs, and the average participant dropout rate ranged from 8.3% to 79%. Also, participant inclusion criteria limited generalizability, especially given the ultimate gender breakdown with the majority of enrolled patients being woman. Pharmacists also tended to lack formal training in the administration of weight management programmes, and in the majority of studies, it was not possible to determine if recognized weight management guidelines were used to inform the interventions.

The primary strength of this scoping review is that provides a comprehensive update on community pharmacy-delivered weight management programmes. A secondary strength stems from the methodology of scoping reviews which focuses on broad inclusion criteria for the purpose of providing informed guidance for future research directions (see Appendix S1). There are also limitations to this scoping review. To begin, this review focused only on published interventional research. As such, it is possible that other successful weight management programmes have been implemented, but as they have not been published, they would not have been included here. However, given that the included studies had similar weight loss results as studies from other settings, we are confident that the trends observed in these data are legitimate. A second limitation is that this review did not include any study wherein pharmacists acted as a consultant to another healthcare professional. Given the objective of this work, to focus on community pharmacy-led weight management programmes, this would have been inappropriate. However, it is also possible that other successful weight management programmes were not included. Finally, given the diversity of methodological approaches taken to each of the included studies, some of the measures included herein had to be calculated by hand using other available variables. While it is possible that this has resulted in potential error, the calculated values are all consistent with those presented in other studies.

Overall, it appears that weight and obesity management programme interventions delivered by community pharmacies resulted in some weight loss. A finding was also established in a previous review of community pharmacy weight management interventions.24 Furthermore, the amount of weight loss achieved in these studies aligns with evaluations of other weight management programmes in a variety of settings.40, 41 Importantly, previous research has reported that modest weight loss (3–5 kg), such as that achieved in this scoping review, can improve surrogate markers of cardiovascular disease.42 Moreover, studies examining the perceptions of patients, obesity experts and pharmacists and other pharmacy team members revealed a positive perception of pharmacists’ role in weight and obesity management.39, 43-45

Comparing the limitations reported in these studies, and those identified by previous reviews of community pharmacy weight management interventions, it is also noteworthy that many of the previously identified limitations, such as lack of RCTs and non-inclusion of sociodemographic factors, have persisted.22, 25 As such, future community pharmacist-delivered weight and obesity management services should employ study designs with the highest possible rigour and contain a control group, train pharmacists implementing the programme in how to effectively enrol and maintain patient participants in the programme and seek to enrol more men into the programmes. Future programmes should also closely adhere to recognized weight management guidelines, such as those from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on the Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society.46 The use of such standardized programmes allows for comparisons across community pharmacy weight and obesity management programmes, further bolstering the evidence of value of these interventions.

One programme that may be adapted in the community pharmacy setting is, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Diabetes Prevention Programme, which found that intensive lifestyle interventions prevented or delayed the onset of type 2 diabetes better than metformin alone.47 Participants in this 16-session intensive lifestyle intervention programme, who engaged in goal setting, nutrition and exercise counselling and behavioural trouble-shooting, lost an mean of 7 kg and were able to maintain their weight below baseline measures at the 10-year follow-up study.47 Importantly, these sessions were designed to be delivered in patient-centred ways, through group or individual meetings, face-to-face or remotely, suggesting the possibility for adaptation to the community pharmacy setting.47

Finally, while none of the included studies focused on sustainability or scalability of community pharmacy weight management programmes, careful consideration must be made of how these programmes could be integrated successfully. There is a growing recognition that generating new clinical evidence alone is insufficient, rather that knowledge must be linked to an implementation process and embedded within a context that other practitioners can take to their own settings.48 A recent systematic review identified a number of pharmacy practice research studies applying knowledge translation (KT), or implementation research, frameworks and theories that could be applied and tested in the community pharmacy setting.49 However, the authors of this review state that there is not currently enough evidence to recommend any one of these theories or frameworks over another.49 As such, researchers should also turn to reviews like this one and others to identify the KT theory or framework that best applies to their setting and begin to test them.49, 50 Without a theory informing the development of an intervention, it is difficult to know which specific variables contributed to its success or failure, making its application in new settings difficult.

The role of pharmacists within the healthcare setting is increasing and along with this new evidence of the value of pharmacists’ interventions in patient care is being developed.19-23 This is accompanied by evidence from national reports and research findings illustrating the value added by non-physician providers in lowering healthcare expenditure and improving quality of care.51 If pharmacists are going to continue to expand their contribution to the healthcare system in the area of weight and obesity management, studies applying stronger study designs, using evidence-based programmes in diverse practice settings, and considering long-term sustainability are essential.

Conclusion

Obesity continues to have a significant impact on the health and wellness of adults. This scoping review suggests a valuable role for community pharmacies in supporting and educating patients as they work towards weight loss and weight maintenance. However, before that potential can be realized carefully designed studies that overcome the limitations outlined in this review, and that integrate KT theories and frameworks to account for sustainability and scalability must be completed.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The Author(s) declare(s) that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors’ contributions

MR, LMW, and JT, reviewed all identified articles and worked together to synthesize the results and write up the final document. SH provided clinical knowledge and support, assisted with mediating conflicts between reviewers, and assisted with writing up the final document.