Adapting and remodelling the US Institute for Safe Medication Practices’ Medication Safety Self-Assessment tool for hospitals to be used to support national medication safety initiatives in Finland

Abstract

Background

The US Institute for Safe Medication Practices’ (ISMP) Medication Safety Self-Assessment (MSSA) tool for hospitals is a comprehensive tool for assessing safe medication practices in hospitals.

Aims

To adapt and remodel the ISMP MSSA tool for hospitals so that it can be used in individual wards in order to support long-term medication safety initiatives in Finland.

Methods

The MSSA tool was first adapted for Finnish hospital settings by a four-round (applicability, desirability and feasibility were evaluated) Delphi consensus method (14 panellists), and then remodelled by organizing the items into a new order which is consistent with the order of the ward-based pharmacotherapy plan recommended by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. The adapted and remodelled tool was pilot tested in eight central hospital wards.

Key findings

The original MSSA tool (231 items under ten key elements) was modified preliminarily before the Delphi rounds and 117 items were discarded, leaving 114 items for Delphi evaluation. The panel suggested 36 new items of which 23 were accepted. A total of 114 items (including 91 original and 23 new items) were accepted and remodelled under six new components that were pilot tested. The pilot test found the tool time-consuming but useful.

Conclusion

It was possible to adapt the ISMP's MSSA tool for another hospital setting. The modified tool can be used for a hospital pharmacy coordinated audit which supports long-term medication safety initiatives, particularly the establishment of ward-based pharmacotherapy plans as guided by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.

Introduction

Numerous studies in the United States, Europe and elsewhere have drawn attention to the nature and consequences of medication errors.1-3 A medication error is described as any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the health care professional, patient or consumer. Such events may be related to professional practice, healthcare products, procedures and systems, including: prescribing; order communication; product labelling, packaging, and nomenclature; compounding; dispensing; distribution; administration; education; monitoring; and use.4 In order to minimise medication errors and improve medication safety, reliable methods are recommended for assessing medication practices.3

In Finland, the first national medication safety initiatives were introduced in 2006 when the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health developed guidelines for safe medication practices in public and private social and health care units.5 The key of the guidelines was that the provision of medication should be based on a pharmacotherapy plan prepared in the unit as recommended by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.5 The pharmacotherapy plan serves as a tool for defining and managing key elements for medication safety. The pharmacotherapy plan should include the following elements: (1) Description of medicines used and the medication management process in the unit; (2) Ensuring and maintaining personnel's pharmacotherapeutic knowledge and skills; (3) Clarifying personnel's responsibilities, obligations and tasks in medication management; (4) Licensed practices (e.g. administration of intravenous medications); (5) Pharmaceutical services: ordering, storing and compounding of medicines, on-site preparation, return policy of medicines, access to drug information, guidance and advice; (6) Distribution and administration of medicines; (7) Medication counselling and patient education; (8) Evaluation of the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy; (9) Documentation and reconciliation; (10) Systems for monitoring and follow-up of medications.5 However, the Finnish guidelines do not include more detailed single items addressing safe medication practices under each element of the pharmacotherapy plan; neither do they provide any assessment method for evaluating implementation and compliance with the health care unit's pharmacotherapy plan. Pharmacotherapy plans, therefore, could remain superficial or even inadequate both in content and function.

According to the inventory made, few comprehensive and practical tools exists that guide assessment of safe medication practices on hospital wards. The most comprehensive of the tools found is the US Medication Safety Self-Assessment (MSSA) tool for hospitals by Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). The MSSA tool contains items that address the safe use of medications, system improvements and safeguards based on the analysis of medication errors reported to the ISMP Medication Errors Reporting Program.6 The MSSA tool for hospitals has been adapted for use in other countries, e.g. Canada, Australia and Spain.7-9 The tool was released first in 2000, and updated in 2004 and later in 2011.6 However, there is no previous research reporting the adaptation process of the US ISMP's MSSA tool in other countries, adaptation taking also into account differences in healthcare systems.

Aim of the study

The aim of this study was to adapt and remodel the ISMP MSSA tool for hospitals so that it can be used in individual wards as a hospital pharmacy audit tool which would support long-term medication safety improvement initiatives in Finland, particularly the establishment of ward-based pharmacotherapy plans as guided by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.

Methods

Study design and method

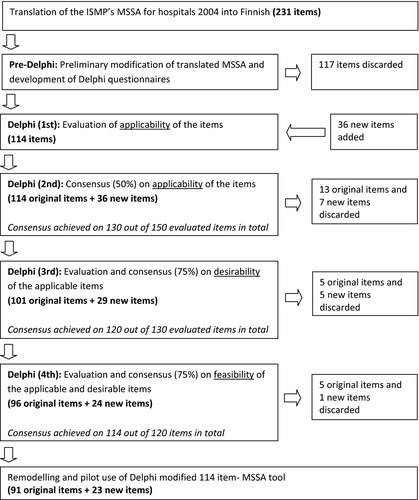

The US ISMP's MSSA tool for hospitals 200410 was first adapted for Finnish hospital settings by a Delphi consensus method, and then remodelled by organizing the items into a new order which is consistent with the order of the ward-based pharmacotherapy plan recommended by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.5 The modified and remodelled tool was then pilot tested in eight medical wards at Satakunta Central Hospital, a 350-bed secondary care hospital on the western coast of Finland serving the Satakunta district with a population of 240 000 inhabitants. The overall study design is shown in Figure 1.

The Delphi is a method for structuring a group communication process so that the process is effective in allowing a group of individuals to deal with a complex problem.11 The Delphi method is an iterative multistage process for deriving consensus among separate expert panels.12 The Delphi method has been recently used in many studies to obtain consensus on different types of healthcare problems, e.g. by developing medication risk management tools and guidelines.13-18

Pre-Delphi modification of the MSSA tool and Delphi rounds

The original US MSSA tool for hospitals 2014 (a total of 231 items)10 was first translated into Finnish and then preliminarily modified before the Delphi panels by the research team members (EC, MM, MA), all of them being licensed pharmacists in Finland and having clinical and academic experience. An item was considered unsuitable and discarded if it could have not been applied to the Finnish healthcare and hospital settings because of the Finnish legislation, inapplicable information technologies or type of practices at that time or in the near future. In addition, since the original MSSA tool for hospitals was designed to assess the implementation of practices in an entire healthcare organisation (hospital), some items of the MSSA were not applicable to be used in assessing an individual hospital ward.

The Delphi method was used for further modification of the tool. The criterion for selecting each expert panellist for the Delphi rounds was that they have extensive clinical experience in pharmacotherapy in hospitals. Selected experts were approached by a letter via email introducing the study protocol and asking their willingness to contribute to the study as an expert panellist. Instructions and the questionnaire in Excel format for each Delphi round were sent to panellists via email. Also responses were collected, as well as reminders were sent by email. Four Delphi consensus rounds were performed. In the first Delphi round, panellists were asked (1) to evaluate the applicability of each item by using a three-point scale (applicable; not applicable; and need for clarification), also (2) to comment on or revise each item according to their opinion, or suggest a new item if necessary. Items that needed clarification at least from one panellist were clarified to all panellists and their applicability was assessed one more time at the second Delphi round. If more than half of the panellists considered an item not applicable, its applicability was also assessed again at the second Delphi round. If more than half of the panellists considered an item applicable in the first Delphi panel, it was moved directly to the third round for the desirability assessment.

In the second Delphi round, panellists were asked to evaluate the applicability of each item by using a three-point scale (applicable; not applicable; and no opinion). Items were accepted for the third round only if considered applicable by more than half of the panellists. In the third round, consensus for desirability (consensus rate: 75%) was questioned for each remaining item. Panellists were asked to evaluate the desirability (effectiveness or benefits)11 of the items by using a three-point scale (desirable/somewhat desirable; no opinion; not desirable/somewhat not desirable). The panellists were again asked to comment on or revise each item according to their opinion, if necessary.

In the final, fourth, round consensus for feasibility (practicality)11 (consensus rate: 75%) was obtained for the remaining items. A three-point scale (feasible/somewhat feasible; no opinion; not feasible/somewhat not feasible) was used. Items on which consensus (75%) was not reached, were discarded.

Remodelling the Delphi-modified MSSA tool and pilot use

The Delphi-modified MSSA tool for hospitals was remodelled by organizing the final items into a new order which was consistent with the recommendation by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health to establish ward-based pharmacotherapy plans in hospitals.5

The Delphi-modified and remodelled MSSA tool was then pilot tested in various wards in Satakunta Central Hospital. All the main medical wards of the hospital were selected for the pilot. The nurse managers of the selected wards were contacted via email to ask their willingness to contribute to the pilot. One of the research team members (EC) first introduced the MSSA tool to the nurse managers of the selected wards in a meeting. The nurse managers conducted the self-assessment in each ward by estimating how well each of the items of the MSSA tool was implemented in the pilot ward's pharmacotherapy plan. A five-point rating scale: fully; partly; poorly implemented; not implemented or not applicable was applied to the self-assessment.

The research team member (EC) then discussed the assessment results with each nurse manager of the pilot ward and prepared ward reports based on each assessment result. In each ward, report medication practices that were inadequately implemented were identified as high-risk areas in the medication management process. Nurse managers of the pilot wards were asked to respond to these reports in one month by addressing the improvements that were implemented based on the MSSA assessment results.

Lastly, the research team member (EC) interviewed the nurse managers of the pilot wards to get feedback from the MSSA tool and its use in practice. It was an open group interview; opinions of the nurse managers of the pilot wards were asked on the comprehensiveness and usefulness of the tool and the amount of time consumed for the practice. The nurse managers of the pilot wards were also asked what would be the most suitable frequency for conducting the MSSA and under whose responsibility the MSSA practice should be coordinated in the future. The responses provided during the interview were collected as hand-written notes. A content analysis was done based on the responses.

Ethics committee's opinion

The local research ethics committee of Satakunta Central Hospital was consulted and according to the research ethics guidelines in Finland, this kind of health services research, not including clinical interventions to patients, does not require research ethics committee's opinion. The pilot testing of the adapted and modified MSSA tool on the wards was conducted under the permission of chief administrative physician. All data processing throughout the study was conducted according to good scientific practice and anonymity of the panellists and those involved in the pilot testing of the new tool was guaranteed.

Results

Participation of the panellists in Delphi rounds

A total of 26 experts were invited, of whom in total 14 participated. Participated panellists were healthcare experts from Finnish healthcare authorities, institutes and organizations with pharmacy (n = 4), medicine (n = 2) and nursing (n = 8) backgrounds. All of the 14 participated panellists completed every Delphi round.

Pre-Delphi modification of the MSSA tool and Delphi rounds

A total of 117 items (51% of the original items) were discarded by the research team within the preliminary modification phase. Thus, the Delphi survey questionnaire for the first and second Delphi rounds included the remaining 114 items, of which 51 items needed clarification at the first panel. A total of 36 new items were suggested by the panellists. Needed clarifications were made and all suggested 36 new items were included in the second round to be evaluated. After the first two Delphi rounds (consensus rate: 50%), a total of 13 original items and seven of the new items were discarded, and out of the accepted original items a total of 32 were revised according to panellists’ responses. Revisions consisted of splitting an item into two different items, combining two items into one item or minor changes due to organizational differences.

A total of 130 items (101 original and 29 new items) were accepted to be evaluated in the third Delphi round. After the third Delphi round (consensus rate: 75%), a total of five original items and also five new items were discarded. The remaining total of 120 items (96 original items and 24 new items) were evaluated to obtain consensus (consensus rate: 75%) for feasibility of the items at the fourth (final) Delphi panel. At the final round, five original items and only one new item were discarded. The finalized Delphi-modified MSSA tool had 91 original items and 23 additional new items (Table 1). Obtained consensus at the third and fourth panels varied between 75% and 100%, however, most of the items (103/114) obtained a consensus rate over 90%.

| Key elements of ISMPs MSSA tool for hospitals13 | Number of items in the ISMPs MSSA tool for hospitals13 | Number of suitable items for assessment after preliminary modification | Number of applicable items after 1st and 2nd Delphi panels | Number of desirable items after 3rd Delphi panel | Number of feasible items after 4th Delphi panel (final) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Patient information | 20 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| 2. Drug information | 30 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 7 |

| 3. Communication of drug orders and other information | 15 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 4. Drug labelling, packaging and nomenclature | 20 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| 5. Drug standardisation, storage and distribution | 35 | 11 | 8 | 8 | 7 |

| 6. Medication device acquisition, use and monitoring | 13 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 |

| 7. Environmental factors, workflow and staffing patterns | 17 | 15 | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| 8. Staff competency and education | 21 | 15 | 15 | 13 | 13 |

| 9. Patient education | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 10. Quality processes and risk management | 49 | 20 | 18 | 18 | 17 |

| Total ISMP | 231 | 114 | 101 | 96 | 91 |

| Additional items | ND | 36 | 29 | 24 | 23 |

- ISMP's, Institute for Safe Medication Practices’; MSSA, Medication Safety Self-Assessment.

Remodelling the Delphi-modified MSSA tool

Table 2 shows the final tool that was reorganized and regrouped under the six main components with sub-contents (Table 3) adapted from the recommendations by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health to establish ward-based pharmacotherapy plans in Finnish hospitals.7

| Key elements of ISMPs MSSA tool for hospitals13 | (I) Main working principles | (II) Pharmaceutical services | (III) Medication use process | (IV) Documentation and reconciliation | (V) Environmental factors, medication devices and monitoring | (VI) Clinical pharmacy services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Patient information | ND | ND | ND | 1, 2, 4, 5, 11 | 10 | 19 |

| 2. Drug information | ND | 48 | ND | 21, 23, 24, 39, 41, 49 | ND | ND |

| 3. Communication of drug orders and other information | ND | ND | 56, 57, 58 | 55, 60 | ND | 65 |

| 4. Drug labelling, packaging and nomenclature | ND | ND | 73, 75, 76, 77, 78, 85 | 67, 68, 82 | ND | ND |

| 5. Drug standardisation, storage and distribution | 89 | 95, 104, 111, 114 | ND | 99 | ND | 107 |

| 6. Medication device acquisition, use and monitoring | ND | ND | ND | ND | 126, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133 | ND |

| 7. Environmental factors, workflow and staffing patterns | 146, 148, 149 | ND | ND | ND | 134, 135, 136, 137, 139, 140 | ND |

| 8. Staff competency and education | 151, 153, 158, 159, 160, 165, 166, 168 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 154, 155, 156, 164, 169 |

| 9. Patient education | ND | ND | 172, 173, 174, 175, 176, 177, 180, 181, 182 | ND | ND | 178 |

| 10. Quality processes and risk management | 185, 187, 192, 195, 199 | ND | 214, 231 | 183, 184 | 202, 204, 205, 208, 209, 227, 228 | 215 |

| Total number of original items | 17 | 5 | 20 | 19 | 20 | 10 |

| Total number of additional items accepted by Delphi consensus | 6 | 11 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Number of original and additional items accepted by Delphi consensus in total | 23 | 16 | 25 | 19 | 21 | 10 |

- ISMP's, Institute for Safe Medication Practices’; MSSA, Medication Safety Self-Assessment.

| (I) Main working principles (17 original items + 6 additional items) |

| Description of medicines used and the medication management process in the unit |

| Ensuring and maintaining personnel's pharmacotherapeutic knowledge and skills |

| Clarifying personnel's responsibilities, obligations and tasks in medication management |

| Licence practices (e.g. administration of intravenous medications) |

| (II) Pharmaceutical services (5 + 11) |

| Ordering, storing and compounding of medicines |

| On-site preparation |

| Return policy of medicines |

| Access to drug information |

| Guidance and advice |

| (III) Medication use process (20 + 5) |

| Prescribing and transmitting the prescription |

| Labelling, distribution and administration of medicines |

| Medication counselling and patient education |

| Evaluation of the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy |

| (IV) Documentation and reconciliation (19 + 0) |

| Patient information |

| Drug information |

| Communication of drug orders and other information |

| (V) Environmental factors, medication devices and monitoring (20 + 1) |

| Working environment |

| Medication device acquisition, use and monitoring |

| Systems for monitoring and follow-up of medications |

| (VI) Clinical pharmacy services (10 + 0) |

| Medication review |

| Patient information |

| Drug information |

- MSSA, Medication Safety Self-Assessment.

Pilot use of Delphi-modified and remodelled MSSA tool

Pilot units were eight various internal medicine wards and they varied in specialty and size (diabetes, haematology, heart, nephrology, neurology, respiratory and two surgery wards). The most fully or partly implemented items were found at component II, ‘pharmaceutical services’ (an average 12 out of 16 items). The least implemented (poorly or not implemented) practices were found at component III, ‘medication use process’ (an average 8 out of 25 items). Improvements, i.e. identifying high-risk medications and implementing double-checking practice, safe storing and labelling practices were made in each subject ward based on the findings of the self-assessment results (Table 4).

| Components of the modified and remodelled MSSA tool | Major improvements made based on the use of modified and remodelled MSSA tool (number of pilot wards made the improvement) |

|---|---|

| (I) Main working principles |

Increased understanding and application of system approach on medication errors (8) Improved open meetings on medication error processing (7) Improved staff education (7) |

| (II) Pharmaceutical services |

Safety-improved storage areas for various medications (8) Updated protocols for preparation of IV medications (8) |

| (III) Medication use process |

Improved medication labelling (8) Improved communication of medication orders (6) Established double-check protocol (8) Updated patient education protocols (6) |

| (IV) Documentation and reconciliation |

Updated protocols for safe medication in patients with renal and liver failure (7) Updated protocols for safe use of opiates (8) Improved identification of look-a-like medications (8) Established policy on using previous medication of patients (8) |

| (V) Environmental factors, medication devices and monitoring |

Improved safety check of infusion pumps (6) Established safe storage instructions for electrolytes to be diluted before use (i.e. KCl) (8) Improved awareness on estimating environmental factors from the error prevention aspect (8) |

- MSSA, Medication Safety Self-Assessment.

According to the nurse managers of the eight pilot wards, adapted MSSA practice was found useful in identifying and improving the high-risk areas in the medication management process. The majority (7 of 8) of the nurse managers believed that the self-assessment could be made on a regular basis, for example, every 2 years to keep the pharmacotherapy plans updated. All nurse managers suggested that the self-assessment practice should be conducted and coordinated by the hospital pharmacy because hospital pharmacists have a different perspective than nurses and doctors working in the wards. Major points of criticism were related to time consumed during the self-assessments: all nurse managers of the pilot wards perceived that the self-assessment tool was too comprehensive and the practice was too time-consuming.

Discussion

It was possible to adapt the original US ISMP's MSSA tool for another healthcare system in spite of differences in legislation and hospital settings by using the Delphi consensus method. The Delphi-modified and remodelled 114 item Finnish MSSA tool was found to be valid for assessing medication management practices in central hospital wards with different medical specialties.

To our knowledge, our study is the only reported study to adapt and remodel the original ISMP MSSA tool for hospitals for another healthcare system. There are two previously published studies reporting results from the use of the original ISMP MSSA tool for hospitals in 2000.19, 20 The cross-sectional survey of U.S. hospitals (n = 1435) using the ISMP's MSSA tool revealed that the participating hospitals scored highest in areas related to drug storage and distribution, environmental factors and medication labelling, while the lowest scores were reported in areas related to patient information, communication of medication orders, patient education and quality processes, such as double-check systems and organizational culture.20 In our pilot study in eight central hospital wards, we received quite similar results with items related to drug storage and distribution being best implemented, while items related to medication order communication and patient education being most poorly implemented.

It must be kept in mind that the pilot users’ perceptions, as presented, are summarised from eight inpatient wards in one teaching, middle sized secondary care hospital in Finland. This number of wards was considered sufficient for pilot testing the modified MSSA tool. We believe that the pilot tested modified MSSA tool is suitable to be used in other hospitals of similar type and size in Finland. It may be applicable also to other type and size hospitals in Finland but it needs to be further tested in those settings.

Prior to the Delphi rounds, nearly half of the items of the original MSSA tool were discarded due to Finnish legislation and medication management practices on the hospital wards. On the other hand, a notable number (n = 23) of new items were derived from the Finnish healthcare context and practices and included in the final tool. It means that 20% of the items in the modified tool were derived from the Finnish health care context and practices. This demonstrates that the adaptation process needs to take into account contextual aspects: it cannot be based solely on linguistic translation. Some of the items in the final modified version were kept even though the practices did not exist at that stage in Finland, but the items were regarded as performing as a stimulus for their desired adaptation.

Despite being time consuming, the pilot users were all convinced that all the items of the adapted tool were necessary to assess safety of medication practices in the pilot wards. Pilot users suggested that MSSAs should be carried out on a regular basis, for example, every two years to keep the ward-based pharmacotherapy plans updated. Pilot users also suggested that the self-assessments should be managed and coordinated by the hospital pharmacy as was done in the pilot project. Pharmacist-conducted MSSAs could perform as facilitators for enhanced and goal-oriented collaboration between hospital pharmacies and clinical wards in improving safety of medication practices.

Similar adaptation and use of the MSSA tool in other countries, e.g. in Europe could provide new opportunities to improve medication safety in hospitals. We highly recommend an adaptation and remodelling process before the use of the original ISMP MSSA tool as health systems, practices and regulations vary in different countries. Before it can be used in other countries it needs to be adapted to follow the local health care system and regulations guiding medication safety.

National Guidelines for Safe Pharmacotherapy, established by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health in 20065 are currently undergoing an update by the National Institute for Health and Welfare, the coordinator of the national patient safety programme in Finland. The update of the Guidelines will be building on our results in the following ways: This adaptation process and its pilot together with experiences of the use of the modified MSSA tool in other hospitals show that the updated guidelines should have more detailed content and practical tools to support safe medication practices. Secondly, our experiences from the adapting process as well as later experiences in other hospitals show that the Finnish MSSA tool for hospitals can function as an essential component of the Guidelines for Safe Pharmacotherapy. Finally, more effort is needed to promote its use regularly in hospitals and to integrate the practice as a part of national patient safety policies in Finland.

Conclusion

It was possible to adapt the original US ISMP's MSSA tool for another health care system, in spite of the differences in legislation and hospital settings, by using Delphi consensus method. The 114-item modified tool can be used as a hospital pharmacy managed audit tool which would support long-term medication safety improvement, particularly the establishment of ward-based pharmacotherapy plans as guided by Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors of this manuscript have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements

Authors gratefully thank Dr Allen Vaida, Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) for the permission to use the ISMP's MSSA tool for hospitals 2004 for this study; Mikko Lahtinen, BSc (Pharm) and Varpu Oinas, BSc (Pharm) for translating the original MSSA tool to Finnish; the experts in the Delphi consensus panels and the chief nurses of the pilot wards for their valuable contributions. Special thanks go to Leena Astala and Dr Joni Palmgren, Chief Pharmacists of Satakunta Central Hospital at the time of the study, for facilitating and supporting this research project. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors’ contributions

Ercan Celikkayalar: Substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; and the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work; Drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; Final approval of the version to be published; Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Minna Myllyntausta: Substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; Revising the work critically for important intellectual content; Final approval of the version to be published; Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Matthew Grissinger: Substantial contributions to the analysis of data for the work; Revising the work critically for important intellectual content; Final approval of the version to be published; Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Marja Airaksinen: Substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; and the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work; Drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; Final approval of the version to be published; Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

All Authors state that they had complete access to the study data that support the publication.