Content validation study on the Advanced Practice Role Delineation Tool

Funding information: This study received no specific external funding.

Abstract

Background

Role understanding and practice standards become extremely important in countries that are developing and assessing nursing and advanced practice nursing (APN) roles.

Aim

To describe the process and findings of a content validation study conducted on the Advanced Practice Role Delineation (APRD) tool in a Finnish context.

Design

A tool content validation study.

Method

Between September and October 2019, three rounds of surveys (n = 9, n = 8, n = 5) were conducted to assess the content validity of the APRD tool. Furthermore, a thorough literature review was conducted in December 2020 to examine how the tool has been used and validated between January 2000 and December 2020.

Results

A 45-item amendment of the APRD tool was created. The Scale Content Validity Index Average of 0.97 reflects excellent content validity. A literature review of 15 studies revealed that the tool has been used by many researchers, yet there is limited research on its content and construct.

Conclusion

The steps taken in this study were effective and may be replicated in other countries. Further studies are needed to validate the content and structure of the developed 45-item modification of the APRD tool.

Highlights

- As specialist and advanced practice nursing roles are implemented increasingly around the world, established frameworks and practice standards will be beneficial for countries developing these roles.

- The Advanced Practice Role Delineation tool has been increasingly used to delineate nursing and advanced practice nursing roles.

- Based on the content validation study on the Advanced Practice Role Delineation tool, a 45-item modification of the tool was created.

- The item content validity index of the modified 45-item Advanced Practice Role Delineation tool varied between 0.88 and 1.00, reflecting excellent item validity. The scale content validity index average was 0.97, indicating high content validity and acceptability of the modified tool within a Finnish context.

- The Advanced Practice Role Delineation tool has been validated for use in the Finnish context, and the generalizability of the results may be limited in other countries. Further research is needed to validate the content and construct of the modified tool across countries.

- The modified Advanced Practice Role Delineation tool may be utilized to develop, standardize and delineate various nursing and advanced practice nursing roles within health-care organizations.

1 INTRODUCTION

Advanced practice nursing (APN) is often used in the literature as an all-encompassing umbrella term referring to an advanced level of clinical nursing at the graduate education level that maximizes the use of in-depth nursing knowledge and expertise in meeting the health needs of individuals, families, and diverse populations (International Council of Nurses [ICN], 2020; Parker & Hill, 2017; Sheer & Wong, 2008). APN roles are a global phenomenon highlighted by several organizations and white papers as a central strategy of the future of nursing to ensure safe, equitable, accessible and more effective use of health-care provider expertise (Maier et al., 2017; Shalala et al., 2011). Therefore, it is important to establish clear definitions of nursing roles, such as nurse practitioners (NPs) and clinical nurse specialists (CNSs). It is essential for stakeholders to distinguish among general, specialist, and APN roles and to create frameworks and practice standards that can guide countries in their efforts to develop, implement and evaluate these roles.

1.1 Background

Practice activities refer to what individuals do in their roles, revealing the knowledge and skills required (Fraser & Greenhalgh, 2001). For effective workforce planning and human resource management, it is essential to identify the various activities of different groups of nurses. The Strong Model of Advanced Practice was developed in the United States during the 1990s (Ackerman et al., 1996) to identify APN activities and domains of practice and create a usable framework to guide practice and role development. The model described the blended role of NP and CNS that was in place at the time. A continuum of experience from novice to expert was identified within the recognized domains of practice of Direct Comprehensive Care, Support of Systems, Education, Research, and Publication and Professional Leadership (Ackerman et al., 1996). In recent years, the Strong Model of Advanced Practice and its modifications (e.g. Advanced Practice Role Delineation [APRD] tool) have been used around the world to differentiate and examine nursing and APN roles (Jokiniemi, Tervo-Heikkinen, et al., 2022). Although the use of the Strong Model of Advanced Practice and APRD tool has increased internationally in the past few years, there is little research-driven information on the validation of the content and construct of the original and modified tool.

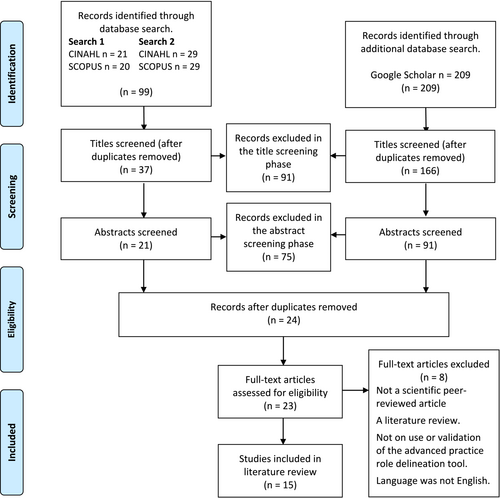

To identify and describe the usage and validation of the original Strong Model of Advanced Practice and modified APRD tool, we conducted a comprehensive review of the literature with the help of an academic health sciences librarian in February 2021. Our search was conducted on CINAHL, Scopus and Google Scholar to gather relevant information between January 2000 and December 2020. The keywords for searching the databases included ‘advanced (nursing) practice’, ‘strong model’, ‘strong APN model’, ‘role delineation’ and ‘APRD tool’. To ensure a thorough search, we conducted two separate searches on CINAHL and SCOPUS. The following inclusion criteria were used: (a) peer-reviewed articles between 2000 and 2020 published in English; (b) focus on the Strong Model of Advanced Practice OR APRD tool; and (c) use or validation of either one of the tools.

After removal of duplicates, 37 articles were identified from the database search (CINAHL and Scopus) and 166 from the Google Scholar search. The literature selection from CINAHL and Scopus was conducted independently by two review authors (N.N, N.N), first on the title and then on the abstract and full-text levels. The title and abstract level selection on Google Scholar were conducted by N. N, after which the full-text selection was conducted independently by two research authors (N.N, N.N). After the selection process, 15 articles were identified for the review and rated for their validity. (Figure 1).

The identified studies (n = 15) were conducted in six countries: the United States (n = 1), Singapore (n = 1), Spain (n = 2), Australia (n = 8), New Zealand (n = 2) and Canada (n = 1). (Table 1) The original Strong Model of Advanced Practice and its modification, APRD tool, have been used to differentiate nursing and APN roles (Duffield et al., 2019; Gardner et al., 2013; Mick & Ackerman, 2000), to provide an overview of the practice patterns and profiles (Sevilla, Miranda Salmerón, & Zabalegui, 2018; Spooner et al., 2019; Woo et al., 2019) and to describe the time spent on APN activities (Spooner et al., 2019; Wilkinson et al., 2018; Woo et al., 2019). Several articles also scrutinized the variability of different titles used in nursing workforce positions (Carryer et al., 2018; Duffield et al., 2019; Gardner et al., 2016; Gardner et al., 2017). In addition, the APRD tool has been used to survey the relationship between the level of education and domain practice scores (Duffield, Gardner, Doubrovsky, & Adams, 2020; Wilkinson et al., 2018) and to test the hypothesized model of the relationship among educational structural empowerment, NP role competence, patient safety competence and psychological empowerment (Duff, 2019).

| Authors, title, country and year | Aim | Methods and participants | Analysis | Main results | Quality appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carryer J, Wilkinson J, Towers A & Gardner G. Delineating advanced practice nursing in New Zealand: a national survey. New Zealand. 2018. | To identify the differences in practice between advanced practice and other roles. To identify advanced practice roles within nursing in New Zealand. | Replicating Australian research (Gardner et al., 2016) with the amended APRD tool. n = 3255 RNs/NPs. Midwives and non-clinical nurses were excluded. | Descriptive statistics. Domain mean scores by one-way ANOVA. Significant results analysed with Scheffe's procedure of post hoc comparisons. | Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.94 (range from 0.80 to 0.93). Twenty-nine position titles were found from which five were most reported nursing positions in NZ. Four bands of nursing position titles were identified, and there were significant differences in domain scores between the four bands. In addition, CNSs and NPs had the most similarities in their practice profile, although NPs were more involved in professional leadership and direct care than CNSs. | * 6/8 |

| Chang M, Gardner GE, Duffield C, Ramis M-A. Advanced practice nursing role development: factor analysis of a modified role delineation tool. Australia 2012. | To determine the construct validity of the modified APRD tool. | A postal survey, the modified ARPD tool. A stratified random sample of state government-employed RNs/midwives in Queensland, Australia. All levels of practice (grade 5 to 7) but NPs (grade 8) were excluded. One thousand five hundred ninety-four nurses were asked to participate; 658 completed the questionnaire. | Descriptive analyses. Exploratory factor analysis, Cronbach's alpha coefficient. | Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.94 (range between 0.83 and 0.95). Five factors were named as in the original APRD tool. One item was loaded below the 0.40 cut-off level and was not included in any factor, and one factor was loaded in two factors and moved into the stronger factor loading domain. One item was loaded to a different domain than in the original APRD tool. The modified APRD tool was able to represent the APN activities in the five domains of practice. | * 6/8 |

| Chang AM, Gardner GE, Duffield C & Ramis M-A. A Delphi study to validate an advanced practice nursing tool. Australia. 2010. | To validate the APRD tool in a contemporary health service context. | A three-round Delphi study. Data collection from an expert panel was conducted via an online survey combined with emails. Expert panel members (n = 16) | Statistical analyses, CVI of 0.75 with activities rated 3 or above were considered an acceptable level of consensus with APN domains and activities. The panel members gave comments on the domains of practice before reading and rating the activities. | Three-round Delphi panel (n = 16), one member discontinued after round 1. Round 1: All five domains achieved the consensus. Five of the 42 activities did not reach a consensus. No activities were removed, nor were new ones suggested. Round 2: Only small differences in the mean scores. The five activities with lower previous scores were still below the level of consensus. One activity was deleted, and one activity was divided into two separate activities (4.6 a and b). Rewordings were created. Round 3: Only the six activities below the 75% CVI cut-off level were evaluated, of which all except one achieved the consensus. Because of indecision, this low-scoring activity with new wording was left to the next phase of the study project. The activity about initiating and identifying diagnostic-related tests was not included in the modified APRD tool. Some wordings were renewed. | * 6/8 |

| Duff E. A structural equation model of empowerment factors affecting nurse practitioners competence. Canada. 2019. | To test a hypothesized model of the relationships among educational structural empowerment, psychological empowerment, NP role competence and patient safety competence. | A non-experimental cross-sectional survey APRD tool was one part of the survey, which consisted of five parts. The APRD tool was used to measure NP role competence. One hundred ninety newly graduated NPs (NP programme completed the survey during the preceding two years) across Canada. | Structural equation modelling (SEM). The NP role competence measurement was conducted by using EFA to determine factor structure, the need for item reduction, item loadings, correlation, reliability and validity, as well as reduce items for SEM analysis. | Five of the six hypotheses were supported. The NP role competence scale was modified to 21 items from 42 items to measure the factor for SEM reliably. Five of the hypotheses were supported. The tasks in the NP role did range in competence, from higher levels for direct clinical practice, education tasks and support of systems, and lower for research and leadership domains. Psychological empowerment partially mediated the positive relationship between NP role competence and educational structural empowerment, but for NP role competence and educational structural empowerment, no mediation effect occurred. | * 6/8 |

| Duffield C, Gardner G, Doubrovsky A & Adams M. Does education level influence the practice profile of advanced practice nursing? Australia. 2020. | To examine the relationship between domain practice scores and the level of education of advanced practice (AP) roles working nurses. | A cross-sectional electronic survey by using the APRD tool. The sample (n = 5599) included 537 participants in advanced practice. | Descriptive statistics were used. Domain means were calculated, and education levels of AP were compared with one-way ANOVA on each domain mean and Student's t-test. | Four different nursing positions were identified as AP based on the profile scores. The nurses working in AP roles with a higher level of education (doctoral or master's degree) got higher mean scores in all five APRD tool domains, especially in the research and leadership domains the differences had wide variability. | * 6/8 |

| Duffield C, Gardner G & Doubrovsky A. Manager, clinician or both? Nurse managers' engagement in clinical care activities. Australia. 2019. | To explore the extent of nurse managers' (NM) engagement in clinical care activities in Australia. | A national survey using the APRD tool. A subset sample: RNs (n = 2758), clinical (front-line) NMs (n = 390) and organizational (middle) NMs (n = 43). | The mean average score for each activity item was calculated for participants. Non-parametric tests were additionally used. | Clinical NMs had a hybrid role, and they had a high level of engagement in every domain. In the domain of ‘clinical care’, the RNs scored significantly higher. The APRD tool did not capture adequately all NMs' managerial and leadership activities even though the NMs undertake the activities in the APRD tool. | * 6/8 |

| Gardner G, Chang AM, Duffield C & Doubrovsky A. Delineating the practice profile of advanced practice nursing: a cross-sectional survey using the modified strong model of advanced practice. Australia. 2013. | To test a model that delineates advanced practice nursing from the practice profile of other nursing roles and titles. | A statewide survey with the modified APRD tool. A random sample of RNs/midwives from government facilities in Queensland, Australia. One thousand five hundred ninety-two nurses were asked to participate, and 660 responded (42%). | Descriptive statistics. ANOVA: Comparing the total and subscale scores of the four groups based on grade. Scheffe's multiple comparison tests: in determining the statistical differences between groups. | The modified APRD tool is suitable for differentiating between advanced practice nurses (grade 7) and standard RNs/midwives (grades 5 and 6) in all APN activities of all five domains. All APN domains of practice were scored higher by grade 7 nurses working in clinical roles than by those in other grade 7 roles. | * 6/8 |

| Gardner G, Duffield C, Doubrovsky A & Adams A. Identifying advanced practice: A national survey of a nursing workforce. Australia. 2016. | To delineate and identify advanced practice from other levels of nursing practice. | A cross-sectional electronic survey of nurses by using the APRD tool. n = 5662 RNs | Descriptive statistics. Domain means were calculated for each participant. Grouping the nursing position titles and comparing domain means by one-way ANOVA. | Over 70 nursing role titles were found. The amended APRD tool was able to identify the differences between different nursing titles. The delineation between advanced practice roles and non-advanced practice roles is possible with the APRD tool. The nurses working at the advanced level had high mean scores in every domain of the APRD tool. The differences between APN role profiles were identified also. | * 6/8 |

| Gardner G, Duffield C, Doubrovsky A, Bui UT & Adams M. The structure of nursing: A national examination of titles and practice profiles. Australia. 2017. | To identify the practice patterns of the Australian RN workforce according to position title, to map the disparate titles across all jurisdictions of the country. | A national cross-sectional electronic survey of RNs in Australia by using the APRD tool. n = 5599. | Descriptive statistics and cluster analysis were used. | Fifty-four different nursing position titles were found. Seven clusters were identified. Different nursing roles and titles can be classified into seven homogenous clusters with delineated practice profiles. | * 6/8 |

| Mick DJ & Ackerman M. Advanced practice nursing role delineation in acute and critical care: Application of the strong model of advanced practice. The United States. 2000. | To differentiate between the acute care NPs and CNSs. | Exploratory, descriptive pilot study. A questionnaire: Self-ranking expertise in practice domains, valuing of role-related tasks. Expert panel (n = 18) of advanced practice nurses had evaluated the content validity of the instrument. | Descriptive statistics. | The strong model of advanced practice supports the differentiation between the CNS and ACNP roles. According to this pilot study, the model was able to describe the CNS practice to a greater degree than the ACNP practice. In all domains, CNSs with experiences as RNs and in APN roles ranked experience higher than ACNPs. The ACNPs did place the direct comprehensive care-related tasks of higher importance. The CNSs, in turn, gave higher importance to education, leadership and research-related tasks. | * 6/8 |

| Sevilla Guerra S, Miranda Salmerón & Zabalegui A. Profile of advanced nursing practice in Spain: A cross-sectional study. Spain. 2018a. | To explore the practice and extent of advanced nursing practice activities. | A cross-sectional study. A purposive sample of specialist nurses and nurses with extended practice profiles. n = 165 | Statistical analysis. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the performance of APN activities according to sample characteristics. Logistic multivariate regression models were constructed to analyse the independent factors associated with APN activities. | The association between the six APN practice domains and the current nursing position was found to be statistically significant. The nursing position and professional career had a greater effect on APN domains, age and educational level and a lesser effect on experience. Years of experience and age had an association with education, professional leadership and interprofessional collaboration. Higher educational level (at least a master's degree) was associated with research, evidence-based practice, professional leadership and interprofessional collaborations. Nursing grade on the hospital career ladder was found to have a strong relationship with most domains. | * 6/8 |

| Sevilla Guerra S, Rusco Vilarasau E, Giménez Galisteo M & Zabalegui A. Spanish version of the modified advanced practice role delineation tool, adaptation and psychometric properties. Spain. 2018b. | To translate, cross-culturally adapt and psychometrically test the Spanish version of the modified APRD tool. | A cross-sectional survey. A purposive sample (n = 151) of specialist nurses and nurses with extended practice profiles. | Construct validity was studied using EFA. Based on the results of EFA, CFA was used to establish the ‘best fitting’ model. Internal consistency was examined using Cronbach's alpha. | The Spanish version of the APRD tool was modified to a six-domain model with 38 items. The validity and reliability of the tool were supported by APNs in community and tertiary hospitals. The modified Spanish tool showed internal consistency, with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.86 and stability over time. | * 6/8 |

| Spooner AJ, Booth N, Downer T-R, Gordon L, Hudson AP, Bradford NK, O'Donnell C, Geary A, Henderson R, Franks C, Conway A, Yates P & Chan R. Advanced practice profiles and work activities of nurse navigators: An early-stage evaluation. Australia. 2018. | To describe the nurse navigators' (NN) advanced practice profile and activities among NNs providing a service for patients with chronic health conditions. | An observational study (part 1: a cross-sectional survey and part 2: an audit of a prospective work activity diary) in four health services, in Queensland, Australia. All NNs (n = 29) were invited, n = 23 responded to part 1, n = 18 to part 2. | Descriptive statistics to summarize the data from both parts of the study. Retrospective categorization of the work activity diaries into five domains of the APRD tool. | NNs were performing activities mostly in three domains: Direct comprehensive care (e.g. performing medical diagnosis), support of systems, and education (especially patient and family education). The nurses spent little time on the activities that were included in the domains of research and publication and professional leadership. | * 6/8 |

| Wilkinson J, Carryer J & Budge C. Impact of postgraduate education on advanced practice nurse activity—A national survey. New Zealand. 2018. | To explore the extent of advanced practice nursing activities associated with various levels of nursing education among nurses working in clinical practice. | A national online cross-sectional survey of RNs and NPs. Total n = 3255, incl. 84 NPs in New Zealand. | The means were calculated for the five domains of the APRD tool. Means were compared with one- and two-way ANOVAs. Post hoc comparisons were performed. | Four groups were compiled based on the level of nursing education, representing entry-level qualifications. PhD graduates (n = 15) were excluded. A positive association was found between the level of nursing education and scores in each domain and was stronger in some domains than others. Higher scores in all domains were associated with higher education. Nurses in APN roles spent more time on direct care than nurses in non-APN roles. | * 6/8 |

|

Woo BFY, Zhou W, Lim TW & Tam WWS. Practice patterns and role perception of advanced practice nurses: A nationwide cross-sectional study. Singapore. 2019. |

To provide an overview of the advanced practice nurses' practice patterns. To explore advanced practice nurses' perceptions of their role in Singapore. | Cross-sectional nationwide online survey. The APRD tool was one part of the survey which consisted of five parts. n = 87 APNs (response rate 40.8%). | Descriptive analysis. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Content analysis of the open-ended questions. Cohen's kappa was calculated to establish the reliability of the content analysis. | APNs participated in activities in all domains of the APRD tool. The greatest extent of time was used on direct comprehensive care and education. Least time was used on the domains of ‘research’ and ‘publication and professional leadership’. APNs did recognize the importance of the other domains (research, publication, professional leadership) although less time was spent on these activities. | * 6/8** 7/10 |

- Note: ACNP = acute care nurse practitioner; ANOVA = analysis of variance; AP = advanced practice; APN = advanced practice nursing/nurse; APRD = advanced practice role delineation; CNS = clinical nurse specialist; CVI = content validity index; EFA = exploratory factor analysis; NM = nurse manager; NN = nurse navigator; NP = nurse practitioner; RN = registered nurse, SEM = structural equation modelling. * = JBI Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies (criteria 5 and 6 were N/A in all of the assessed studies because of study design), ** = JBI Checklist for Qualitative Research.

Three articles described the validation process of the Strong Model of Advanced Practice, whereby the tool was validated in terms of the content and construct in Australia (Chang et al., 2010, 2012) and Spain (Sevilla, Vilarasau, et al., 2018). Within these studies, the content of the Strong Model of Advanced Practice was slightly modified to clarify wordings. The modified tool was called the APRD tool. The construct of the APRD tool was found consistent with the Strong Model of Advanced Practice within Australia. However, variation existed in the sample from Spain, where the results of an exploratory factor analysis displayed a different theoretical underlying factor structure (Sevilla, Vilarasau, et al., 2018).

Based on the literature review, we conclude that the Strong Model of Advanced Practice and APRD tools have been used to describe and differentiate nursing and APN roles and education; however, there is limited research on the content and construct validation of the tools. Although previous research has examined the content of the Strong Model of Advanced Practice (Chang et al., 2010; Sevilla, Vilarasau, et al., 2018), no major modification to its content (APN activity items) has been carried out after its development in the 1990s. Because of the changes in health-care services during the last two decades, a content validation of the APRD tool was needed prior to the use of the tool in the Finnish context.

Finland is among the countries that introduced the APN role around the turn of the century. Over the past 20 years, there has been a national effort to conceptualize advanced-level nursing roles (Jokiniemi et al., 2019), but there is little information on the variability of generalist, specialist and advanced nursing activities. None of the APN roles are regulated, although the role of CNS is well recognized, while the NP role is more unclear (Jokiniemi, Heikkilä, et al., 2022). To investigate nursing and APN roles, the APRD tool was considered a purposeful tool with the potential to guide the development and evaluation of these roles. The lack of validation research combined with the increasing number of the APN roles highlights the importance of this study examining the content validity of the APRD tool in the Finnish context. The process described can be replicated in other countries utilizing and validating the Strong Model of Advanced Practice or APRD tools. Furthermore, suggested new items can be added to the APRD tool in future examinations of the nursing and APN roles.

2 METHODS

2.1 Aims

The aim of this study was to describe the process and findings of a content validation study conducted on the APRD tool in a Finnish context.

2.2 Methodology

A content validation study was performed to assess a 41-item APRD tool. In content validity assessment, the representativeness of the content of an instrument is determined with a predetermined process (Lynn, 1986). We invited APN experts to judge the content of the APRD tool with the specific objectives of (a) examining the content of the APRD tool items by evaluating each item's relevancy on a 4-point, Likert-type scale (0 = very irrelevant to 3 = extremely relevant); (b) identifying any missing items; and (c) examining and clarifying the wording of the translated APRD tool. A meticulous step-by-step process of development and judgement quantification was carried out to establish and quantify the instrument's content validity (Lynn, 1986).

2.3 Sampling and participants

For this study, the research team utilized purposive sampling as described by Panacek and Thompson, 2007. The experts with a high level of knowledge or skill relating to APN were identified by the research team knowledgeable about the APN expert positions in Finland. To reach wide expertise, we invited APNs, nurse educators and experts in workforce planning who were familiar with national and/or international APN roles and research. Participants were asked to evaluate their own expertise in APN roles and health-care practice environments using a scale that ranged from 0 (no expertise) to 3 (high expertise). According to the method described by Lynn (1986), between 5 and 10 experts provide a sufficient level of control for change agreement; therefore, a total of 12 experts were invited in August 2019 to participate in the study.

2.4 Validity and rigour

2.4.1 Tool description

In this study, we used the APRD tool created by an Australian research team (Chang et al., 2010, 2012). The tool was created based on the Strong Model of Advanced Practice, which was designed by a group of APNs and academic faculty members at Strong Memorial Hospital, University of Rochester Medical Center (Ackerman et al., 1996). The APRD tool includes no new items compared to the Strong Model of Advanced Practice. However, there has been some clarification of activity items, leading to a 41-item tool in the five domains of practice: Direct Comprehensive Care (15 items), Support of Systems (eight items), Education (six items), Research (six items), and Publication and Professional Leadership (six items) (Gardner et al., 2013). All domains include both direct and indirect care activities, but the emphasis on each domain may differ depending on the requirements of the practice (Mick & Ackerman, 2000).

2.4.2 Tool translation

The APRD tool went through a translation process from English to Finnish by two professional translators. The translations were examined and assessed by native Finnish-speaking research team members in terms of meaning, accuracy, wording and grammar (Squires et al., 2013). Afterwards, the survey, which included demographic questions and the APRD tool, was tested with two participants who met the inclusion criteria for the upcoming research. Feedback was requested on clarity and understanding of the questions and language used as well as functionality and the appropriateness of the length of the survey. As a result of this feedback, minor revisions were made to the survey.

2.5 Data collection

All data were collected over three iterative data collection rounds using a Web-based self-report survey between September 2019 and October 2019 (n = 9, n = 8, n = 5). The survey consisted of closed and open-ended questions. During the first round, the participants were asked to independently evaluate the 41 APRD items on a Likert scale in terms of their relevancy (0 = irrelevant to 3 = extremely relevant) and identify any issues with clarity of wordings in the translated tool. If the participant had rated an item as ‘very irrelevant’ or ‘irrelevant’, they were requested to give the reasoning behind their rating. The participants could also clarify items and evaluate the structure of the APRD subscales. In the second round, the same expert panellists who had participated in the first round were asked to evaluate any items requiring clarification or that had received low Item Content Validity Index (I-CVI) scores in the first round. In addition, the expert panellists were asked to provide additional activity items if needed. In the third round, new items identified during the second round were rated.

2.6 Data analysis

In the data analysis, both qualitative and quantitative analysis methods were used. Qualitative content analysis (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004) was used to analyse the data from the open-ended questions to condense, organize and group the responses. Quantitative data were analysed by using descriptive statistics to summarize the demographic characteristics of participants. From the participant relevancy ratings, we measured I-CVI. To obtain the I-CVI scores, we divided the number of ratings 2 and 3 by the total number of respondents (n = 9). For more than six raters, the I-CVI should be over 0.78. The Scale CVI Average (S-CVI/Ave) was calculated by adding up all I-CVIs and dividing the sum by the total number of items. To meet the standard criterion for scale content acceptability (Lynn, 1986), S-CVI/Ave should be above 0.90.

2.7 Ethical considerations

The research methods employed in this study are both ethical and sustainable. The University of Eastern Finland's Committee on Research Ethics provided an ethical statement (Statement no. 22/2018). Each participant was approached individually and presented with an information sheet that contained a link to the survey. Furthermore, they were provided with an information sheet about the study, which consisted of a link to the survey. Completion of the e-survey was regarded as implied consent to participate, of which the participants were informed. Voluntary participation was reinforced with the possibility of ceasing participation at any point in time.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Participant demographics

Twelve experts were invited to participate, and nine experts consented to participate, yielding a response rate of 75. The respondents' (n = 9) mean age was 46 years. Over half (67%, n = 6) worked in a specialist medical health-care context (specialist nurse [n = 1], NP [n = 2], CNS [n = 2] and nurse consultant [n = 1]), one was from an educational organization (head of education [n = 1]), and two were from professional health-care organizations (consultant position [n = 2]). The participants self-evaluated their experience (on a scale of 0 = no expertise to 3 = high expertise) in specialist nursing roles as 1.8, in CNS roles as 2.9, in NP roles as 1.9 and in nursing practice environments as 2.3.

3.2 APRD tool content validation

In the first round, a panel of nine experts (with a response rate of 75%) evaluated 41 activities in relation to Finnish health care on a scale of 0 (very irrelevant) to 3 (extremely relevant). Based on the first-round analysis, 38 out of 41 items received an Item Content Validity Index (I-CVI) above the cut-off point of 0.78. However, three items did not meet the cut-off point: ‘4.3 Contributes to the identification of potential funding sources for the development and implementation of clinical projects/programmes’ (I-CVI 0.67), ‘1.4 Identify and initiate required diagnostic tests and procedures’ (I-CVI 0.67), and ‘1.3 Make a medical diagnosis within specialty scope of practice and practice guidelines’ (I-CVI 0.44). The participants did not request any changes to the domains of the subscale items; however, two major and four minor wording clarifications were suggested. (Table 2).

| Round | Items requiring clarification in various rounds | I-CVI |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Items below cut-off point after first round | |

| 1.3 make a medical diagnosis within specialty scope of practice and practice guidelines | 0.44 | |

| 1.4 identify and initiate required diagnostic tests and procedures | 0.67 | |

| 4.3 contributes to identification of potential funding sources for the development and implementation of clinical projects/programmes | 0.67 | |

| 2 | Modified items re-rated during second round | |

| 1.4 recognition and implementation of required diagnostic tests according to the formulated care plan | 0.88 | |

| 3.4 guidance/teaching of staff in the context of direct patient care | 0.87 | |

| 4.3: Recognition of possible funding sources for the development and execution of own clinical projects | 1.00 | |

| 5.2 serve in professional organizations as a member of working groups and committees | 1.00 | |

| 3 | New items recognized during second round and rated in third round | |

| Integrate evidence-informed practice procedures (domain of support of systems) | 1.00 | |

| Promote the innovation activity within own practice area (domain of support of systems) | 1.00 | |

| Facilitate the implementation of changes (domain of support of systems) | 1.00 | |

| Develop and conduct of staff education programmes (domain of education) | 1.00 | |

| Evaluate nursing staff competence (domain of education) | 1.00 |

- Note: I-CVI = Item Content Validity Index.

In the second round, a group of eight participants (response rate 89%) provided feedback on four items that had been previously rated in the first round. Based on their feedback, two items with an I-CVI value of 0.67 were rephrased, whereas two items underwent major changes. In addition, two items were amended with major wording changes suggested by the participants. The item ‘Make a medical diagnosis within specialty scope of practice and practice guidelines’ (I-CVI 0.44) was not subjected to further rating as the participants indicated during the first round that medical diagnosing is not within the scope of nursing practice in Finland, as physicians exclusively perform it in accordance with the law. As a result of the revisions, all four items that were reassessed during the second round received an I-CVI above the cut-off point. (Table 2).

During the second round, the participants were also asked to identify any missing items in the APRD tool. In response, they recognized a total of five new items. Three of these items belonged to the domain of support of systems: ‘integrate evidence-informed practice procedures’, ‘promote innovation activity within own practice area’, and ‘facilitate the implementation of changes’. The other two were associated with the education domain: ‘develop and conduct staff education programmes’ and ‘evaluate nursing staff competence’.

In the third, the participants (n = 5, 67% response rate) who took part in the second round were asked to rate five new items identified during the second round. All five new items received an I-CVI of 1 (Table 2). Overall, the I-CVIs of the 45-items varied between 0.88 and 1.00, reflecting excellent item validity. Finally, the S-CVI/Ave for the entire scale was counted. A S-CVI/Ave after the first round was 0.95. With the changes suggested by the expert panel during the three rounds, the 45-item APRD tool S-CVI/Ave was 0.97.

4 DISCUSSION

As a result of this content validation study, the APRD tool was translated and validated in the Finnish context. Based on the content validation, the logical consistency and the relevance of the APRD tool were evaluated, and gaps in items were identified by the expert panel. The tool was found extremely relevant to the Finnish health-care context through the expert examination and clarification of a few items, the removal of one item, and the addition of five new items. Three items added to the domain of support of systems, reflected the integration of evidence-informed practice, the promotion of innovation activity and the implementation of change. Two items added to the education domain, related to the development, and conduct of staff education programmes and the evaluation of nursing staff competence. The modified 45-item APRD tool is categorized under five original domains of direct comprehensive care (14 items), the support of systems (11 items), education (eight items), research (six items), and publication and professional leadership (six items) (Supplementary file 1). The modified 45-item APRD tool received a high S-CVI/Ave of 0.97, indicating high validity of the whole scale (see Lynn, 1986).

The Strong Model of Advanced Practice and APRD tool are increasingly used around the world and have been found to be able to differentiate nursing and APN roles (Carryer et al., 2018; Gardner et al., 2016; Jokiniemi, Heikkilä, et al., 2022; Sevilla, Miranda Salmerón, & Zabalegui, 2018). Based on the literature review, we conclude that research validating the content and construct of the Strong Model of Advanced Practice or APRD tools is limited. No major modification of the content has been performed since its development in the 1990s yet, because of changes in health-care services, there will be changes in the practice and activities of nurses and APN roles, highlighting the importance of the study. Twenty-first-century nursing practice has advanced in terms of support of systems in multiple realms such as the evidence-based and evidence-informed practice movement (Nevo & Slonim-Nevo, 2011), managing change through implementation science (Rapport et al., 2018) and leadership of innovation activity (Kremer et al., 2019). In addition, the constantly changing health-care environment and rapid information growth has highlighted the need for lifelong learning, which has been recognized as a necessity for the nursing profession. Thus, health-care organizations should collaborate to enable nurses to continue teaching and become involved in lifelong learning to acquire the competence required for the provision of care (Qalehsari et al., 2017). Five new items identified by the expert panel reflect the contemporary changes in nursing and APN activities and modern 21st-century health-care organizations. Future studies will need to validate the use of these activities among nurses in various cultures. The item ‘Make a medical diagnosis within the specialty scope of practice and practice guidelines’ was removed from the Finnish data as it is not in the nurses' scope of practice in Finland. This item can be added to the tool in countries where it belongs to the advanced practice nurses' scope of practice.

Delineating various nursing roles will facilitate role clarity and differentiation and promote the optimal use of health human resources. However, it is important to note that, in addition to the measurement of activity frequency, the Strong Model of Advanced Practice or APRD tools do not necessarily cover all dimensions of APN activities and do not measure the quality of the activities performed (Carryer et al., 2018). Another important aspect of role delineation work is the need to measure the impact of certain activities on patient outcomes. The concept of APN dosage is something that could be developed once the tool has been fully validated. The nursing dosage has been utilized in other research linking dosage to patient outcomes (Manojlovich et al., 2011).

The modified 45-item APRD tool developed in this study may be utilized in nursing education to reflect the realm of generic nursing activities and the various levels of different positions. Furthermore, nursing management may be informed of the complementary nature of nursing roles when making decisions on how to optimally utilize various nursing positions within health-care teams. Finally, the research communities of nursing and APN may elaborate and continue to validate the content and construct of the modified 45-item APRD tool developed in this study. The processes described may be replicated in other countries validating the tools of advanced practice. The modified APRD tool, consisting of 45 items, can be used to examine nursing and APN roles; however, caution is required when utilizing the original or the modified tools to ensure rigorous, legitimate processes and comparability of research results.

4.1 Limitations

The study provides a contemporary content validation of the APRD tool. The study was completed in one country, where APN roles have been developing over the past 20 years. Although the sample size was sufficient for the validation of the competency criteria by experts, the short history of the introduction of APN roles may limit the knowledge of the panel members. Therefore, the 45-item version of the APRD tool has been validated for use in the Finnish context, and the generalizability of the results may be limited in other countries; however, the methods may be replicated to modify the APRD tool in other contexts and circumstances. Further research is needed to validate the content and construct of the modified tool across countries.

5 CONCLUSION

This study describes a content validation process of the APRD tool and a comprehensive literature review on the use and validation of the tool. The study design was developed within a research team experienced in tool validation and development. A clear audit trail was reported to demonstrate the validity and rigour of the processes undertaken. For the first time, the Strong Model of Advanced Practice or APRD tool validation resulted in adding new items to the tool. Added items in the areas of support of systems and education include activities related to evidence-informed practice, the promotion of innovation, the facilitation of change implementation, the development and conduct of staff education programmes and the evaluation of nursing staff competence. These recognized gaps in items illustrated the contemporary changes in nursing practice since the year 1996 when the Strong Model of Advanced Practice was developed. The 45-item modified APRD tool received a high S-CVI/Ave; thus, the scale may be regarded as valid with regards to content in the Finnish context. Further research is needed to validate the content and construct of the 45-item APRD tool across countries. Discretion is needed when changing existing tools, and changes made need to be taken into consideration when comparing the results of APRD studies between different countries.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT

KJ, LH and AMP made contribution to the design, acquisition, and analysis of the empirical study phase. KJ, LH, AMP and MA contributed substantially to the literature review design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the empirical and literature review data. All authors were involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically and gave final approval of the version to be published. Each author participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work were appropriately investigated and resolved.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We express our appreciation to the expert panellists who participated in the study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared.