Effect of consumer self-confidence on information search and dissemination: Mediating role of subjective knowledge

Abstract

Consumers search for information about products to make a satisfactory purchase decision and gain knowledge about new features and updates. Consumers also use this knowledge to be vocal about their product experience because several consumers seek interpersonal recommendations. This phenomenon has contributed to the emergence of information search (IS) and information dissemination (ID) as a key research area in the field of consumer behaviour. However, the role of personal factors such as consumer self-confidence and subjective knowledge has received little attention in the extant IS and ID literature. The major argument of this study is that information acquisition confidence and social outcome confidence enhance subjective knowledge and consequently increase the will of consumers to search and disseminate information in the context of smartphone buyers in India. Structural equation modelling was employed to test the proposed hypotheses using a convenience sample of 259 consumers obtained through a cross-sectional survey. The study shows that subjective knowledge is crucial in strengthening the association between consumer self-confidence and consumer intention for IS and ID. Additionally, enhancing consumer’s social outcome confidence contributes towards high subjective knowledge and consequently accelerates information dissemination. Results suggest that firms could focus on enhancing the social outcome confidence and subjective knowledge of consumers to motivate them to disseminate information. The results also show that consumers with high confidence in information acquisition ability have the high subjective knowledge and are more likely to search for information. Overall, this study contributes to the emerging literature regarding the role of personal factors in IS and dissemination behaviour.

1 INTRODUCTION

The advent of technology has accelerated the pace of information search and sharing. Consumers search for information to gain knowledge about products and market trends. Moreover, consumers are increasingly becoming vocal in disseminating information regarding products. Consumer’s reliance on interpersonal recommendations before buying products has contributed to the emergence of word of mouth. This behaviour creates considerable challenges for marketing communication because marketers encounter the dominance of consumer-controlled information sources (Berger, 2014; Haenlein & Libai, 2017). However, the aforementioned phenomenon provides an opportunity for marketers. Effective marketing programmes can be created if the marketers can understand the personal factors of consumers influencing information search (IS) and information dissemination (ID) (Mowen, Park, & Zablah, 2007; Wein & Olsen, 2017). An improved understanding of personal factors is a primary facilitator in customizing marketing messages, developing consumer engagement programmes, and segmenting markets. Moreover, consumers can be motivated to talk about products by understanding the social and self-motives of disseminating information (Alexandrov, Lilly, & Babakus, 2013; Baker, Donthu, & Kumar, 2016). This study particularly investigated the effect of consumer self-confidence on two crucial determinants of consumer behaviour, IS and ID. Furthermore, we examined the mediating role of subjective knowledge.

This research is in the domain of IS and ID behaviours, where IS represents the intention of the consumer to conduct prepurchase information search regarding a particular product (Dholakia, 2001; Kiel & Layton, 1981; Seock & Bailey, 2008). Researchers gave a considerable amount of attention to the IS domain (Maity, Dass, & Malhotra, 2014); however, less attention was given to personal factors (Dornyei & Gyulavari, 2016; Utkarsh, 2017). Mowen et al. (2007) suggested that personal factors are crucial in the preference of consumers to send and receive information in the market place. In a qualitative study, Dornyei and Gyulavari (2016) emphasized that personal factors play a crucial role in determining the behaviour in the context of label information search. They included product-related knowledge, self-efficacy, trust in labels as few key variables in label information search framework. Similarly, an ID domain constituting consumer tendencies, such as word of mouth and market mavenism, to engage in a marketplace conversation is topical in the marketing and consumer psychology literature (Berger, 2014; Flynn & Goldsmith, 2017; Gauri, Harmon-Kizer, & Talukdar, 2016; Goldsmith, Flynn, & Clark, 2012; Wein & Olsen, 2014). However, personal factors such as consumer self-confidence and subjective knowledge have received limited attention in research (Wein & Olsen, 2017; Yuan, Lin, & Zhuo, 2016).

The paper attempted to fill the following void in the current literature. First, Bearden, Hardesty, and Rose (2001) suggested that high consumer self-confidence should be positively related to market mavenism; that is, a propensity of consumers to seek and share information in the marketplace. Loibl, Cho, Diekmann, and Batte (2009) observed that confidence in acquiring information is negatively related to the IS effort; however, contradictory evidence indicated a positive relationship between consumer self-confidence and IS (Utkarsh, 2017). In the ID domain, Clark, Goldsmith, and Goldsmith (2008) observed that information acquisition and social outcome confidence, two important dimensions of consumer self-confidence are strongly related to market mavenism and suggested the existence of mediating variables that can explain this strong relation. Information acquisition confidence is the consumer confidence in acquiring information from the marketplace (Bearden et al., 2001). Social outcome confidence is the consumer confidence in making socially acceptable decisions and the ability to deal with the social outcome of the purchase decision. Clark et al. (2008) conclusion was the basis for selecting these two crucial dimensions of consumer self-confidence for our research and further examined in a different nomological network, enabling the extension of previous results.

A second gap that should be addressed is the conclusion from the study of Park, Mothersbaugh, and Feick (1994), which indicated that examining the effect of individual differences adds more insights to the formation of subjective knowledge. Subjective knowledge is defined as the individual’s perception of their knowledge level regarding a specific product. Several researchers have focussed on subjective knowledge (Donoghue, Van Oordt, & Strydom, 2016; Hadar, Sood, & Fox, 2013); however, few have explored its antecedents (Park et al., 1994) and ID as a consequence of subjective knowledge (Vigar-Ellis, Pitt, & Caruana, 2015). Thus, the role of the self-confidence of consumers, knowledge perceptions, and their relative influence on the will of consumers to engage in IS and ID is worth examining and forms the nomological network of this research. The major argument of this study is that information acquisition confidence and social outcome confidence enhance subjective knowledge and consequently increase the will of consumers to search and disseminate information.

Furthermore, the effect of personal factors on IS and ID intentions in the Indian context has not been studied. India is considered to be a collectivist country (Hofstede, 1980), where people emphasize on social connectedness and family values (Banerjee, 2008), which may influence the will of consumers to disseminate information (Lam, Lee, & Mizerski, 2009). Moreover, social confidence can be a crucial contributor to self-confidence in collectivist cultures. The relation between consumer self-confidence and market mavenism in collectivist cultures is stronger than that in individualistic cultures (Chelminski & Coulter, 2007a). In addition to filling these gaps, the results of this study are crucial for marketers to devise effective communication programmes for enabling consumers to share information that may provide improved results in collectivist countries, as compared with those in individualistic countries (Lam et al., 2009).

This study advances the literature by studying the relation between consumer self-confidence and subjective knowledge. We complement Bearden et al. (2001), and extend work of Clark et al. (2008) by investigating a mediating variable that influences the relation between consumer self-confidence and the propensity of consumers to engage in the marketplace conversations. Moreover, this research supplements to the emerging literature by establishing that subjective knowledge is crucial in strengthening the relationship between social outcome confidence and ID (Alexandrov et al., 2013; Gauri et al., 2016; Goldsmith et al., 2012; Jurgensen & Guesalaga, 2018). Results show that consumers with high information acquisition confidence have a high subjective knowledge and more likely to search for information. We also found that social outcome confidence is an important facilitator of information dissemination and subjective knowledge fully mediates this relationship. Succinctly, we highlight the mechanism through which consumer self-confidence and subjective knowledge facilitate consumer’s intention to search and disseminate information. The results provide considerable implications for practitioners to accelerate information sharing by understanding personal factors of consumers.

The remaining article is organized as follows: first, the theoretical background is provided along with the conceptual framework; furthermore, the methodology of the study is described; the results are then elaborated; and finally, the discussion and future research directions are presented.

2 THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS

2.1 Consumer self-confidence

Self-confidence is a personality level variable that reflects the belief of individuals in dealing with different situations (Bell, 1967; Jurgensen & Guesalaga, 2018; Keng & Liao, 2013; Locander & Hermann, 1979). Bearden et al. (2001) proposed a multidimensional consumer self-confidence construct and defined it as the ability of an individual to be certain about their decisions and behaviours regarding the marketplace. Consumer self-confidence is a construct with six dimensions, namely information acquisition, social outcome, personal outcome, and consideration set formation, which represents the consumer confidence regarding effective purchase decision making, persuasion knowledge and marketplace interfaces, which represent the ability of consumers to protect themselves from being misled and treated unfairly. Consumer self-confidence is related to the IS effort, word-of-mouth production, market mavenism, information source preference, consumer innovativeness, and decision making ( Utkarsh & Medhavi, 2015; Chelminski & Coutler, 2007b; Clark et al., 2008; Jurgensen & Guesalaga, 2018; Loibl et al., 2009; Paridon, 2006; Utkarsh, 2017). Recently, Jurgensen and Guesalaga (2018) found that self-confidence of young girls is a major contributor to innovativeness in choosing apparels.

Among six dimensions of consumer self-confidence, two dimensions, namely information acquisition confidence and social outcome confidence, are expected to be strongly related to the IS and ID behaviours, respectively (Clark et al., 2008). The relationship of these two dimensions with subjective knowledge and their effect on IS and ID behaviour was examined in this study.

2.2 Subjective knowledge

Consumer knowledge is a primary variable influencing the consumer behaviour (Brucks, 1985; Hadar et al., 2013; Oh & Abraham, 2016; Park et al., 1994). Knowledge includes three components, objective knowledge, subjective knowledge, and past experiences (Alba & Hutchinson, 1987; Brucks, 1985; Flynn & Goldsmith, 1999; Park & Lessig, 1981; Xiao, Ahn, Serido, & Shim, 2014). Subjective knowledge is the belief of consumers regarding their knowledge of the product, in contrast; objective knowledge is what consumer actually knows (Carlson, Vincent, Hardesty, & Bearden, 2008; Park et al., 1994).

When consumers have knowledge regarding a product category, they can efficiently search for information (Moorman, Diehl, Brinberg, & Kidwell, 2004; Punj & Staelin, 1983), and exhibit confidence in their ability to purchase (Brucks, 1985; Park & Lessig, 1981). Consumer knowledge regarding a product enables them to think of more questions and realize the benefit of the search. Moreover, consumers with better knowledge use their existing knowledge and perform an efficient search, reducing the prepurchase search effort (Awasthy, Banerjee, & Banerjee, 2012; Maity et al., 2014).

Objective knowledge is not consistently correlated with subjective knowledge (Carlson et al., 2008; Hadar et al., 2013). Hadar et al. (2013) indicated the existence of “… a well-documented disassociation between objective knowledge and subjective knowledge…”, and previous research (Raju, Lonial, & Mangold, 1995) emphasized on the role of subjective knowledge in the prepurchase search behaviour, which supports our choice of subjective knowledge as a central knowledge construct in the conceptual model of the present study. Rodrigues, Pereira, Silva, Mendes, and Carneiro (2017) also emphasized that subjective knowledge is a strong predictor of behaviour in context of sodium intake.

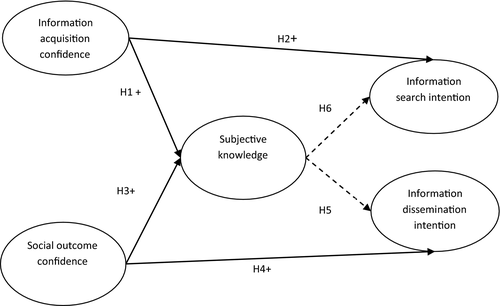

Furthermore, subjective knowledge and its relationship with information sharing has not been given much attention (Yuan et al., 2016). Vigar-Ellis et al. (2015) validated that the opinion leader behaviour in the context of wine consumers is positively influenced by subjective knowledge. In the present study, the role of subjective knowledge in IS and ID was examined. The hypothesized relation between the dependent and independent variables are depicted in Figure 1.

2.2.1 Information acquisition confidence, subjective knowledge, and information search

H1 Information acquisition confidence is positively related to subjective knowledge

H2 Information acquisition confidence is positively related to the IS intention

2.2.2 Social outcome confidence, subjective knowledge, and information dissemination

Consumers with high social outcome confidence are likely to exchange dialogue regarding the purchased products (Berger, 2014; Clark et al., 2008; Paridon, 2006; Wien & Olsen, 2014). The will of consumers to share information is facilitated by their self-confidence (Chelminski & Coutler, 2007a). Social outcome confidence is a better predictor of the consumer tendency to share information and engage in the marketplace conversation than that of the other dimensions of consumer self-confidence, such as personal confidence and persuasion knowledge (Clark et al., 2008).

Consumers share information because their ultimate aim is to satisfy their needs of self-enhancement and self-affirmation, for which they get involved in social interactions (Alexandrov et al., 2013). Paridon (2006) observed that during shopping, the positive experience of consumers generates social outcome confidence that positively influences the information sharing tendency of consumers. The recent evidence of Wien and Olsen (2017) indicated that social outcome confidence is an important predictor of the information sharing propensity of consumers.

H3 Social outcome confidence is positively related to the subjective knowledge of consumers

H4 Social outcome confidence is positively related to the ID intention

2.2.3 Subjective knowledge, information search, and information dissemination

Subjective knowledge influences the IS behaviour (Brucks, 1985); moreover, it is considered to be a better predictor of the search behaviour than objective knowledge (Moorman et al., 2004; Oh & Abraham, 2016; Raju et al., 1995). Subjective knowledge can be considered to be the result of highly objective knowledge and the previous experience (Raju et al, 1995), thereby mediating the effect on decision outcome. Consumers with high subjective knowledge prefer impersonal sources of information, (Barber, Dodd, & Kolyesnikova, 2009; Dodd, Laverie, Wilcox, & Duhan, 2005) indicating their need to update knowledge. Overall, research indicates an equivocal relationship between knowledge and the extent of the search effort (Maity et al., 2014).

Consumers with high subjective knowledge tend to share information, which also reinforces their positive knowledge perceptions (Oh & Abraham, 2016; Packard & Wooten, 2013). Similarly, Donoghue et al. (2016) found that in case of dissatisfaction, consumers with high subjective knowledge are likely to take public action, which means they will complain to retailers, manufacturer, or third parties. Subjective knowledge is a key variable that influences the propensity of consumers to share information in online communities (Yuan et al., 2016). Furthermore, expert consumers are considered opinion leaders (Grewal, Mehta, & Kardes, 2000; Kiani, Laroche, & Paulin, 2016; Vigar-Ellis et al., 2015).

H5 Subjective knowledge mediates the relationship between social outcome confidence and the ID intention

H6 Subjective knowledge mediates the relationship between information acquisition confidence and the IS intention

3 METHOD

The study was conducted in the context of the decision of buying a smartphone. The smartphone is a popular and rapidly growing product category in India with year-on-year growth of 14.8%, and India was expected to have the second largest smartphone user base of 334 million units by the end of 2017, as estimated by International Data Corporation (Wharton, 2017). The Indian smartphone market consists of approximately 40 local and foreign brands, implying that the product involves significant effort in IS, and adequate information is necessary to generate a positive purchase intention (Chang, Tsai, Hung, & Lin, 2015). Consumers associate smartphones with self-image and social image, motivating them to consider buying a smartphone to be a socially important decision (Goldsmith et al., 2012). Lee (2014) found that reference groups influence the purchase of the smartphones. Moreover, it is a product where consumers frequently discuss the offered features and benefits. The average price of a smartphone in the Indian market is approximately INR 7000 (Approx. US$ 100; Knowledge Wharton, 2017). To control the severe variation in the pricing of smartphones and other situational influences, such as giving gifts or purchasing on behalf of a family or friend, all respondents were offered a situation related to the purchase of smartphone. Respondents were asked to consider a situation where they have to buy a smartphone for themselves and have sufficient time to search and evaluate alternatives. Furthermore, they were told that they have a budget of INR 10,000–15,000. This approach ensured the control of the situational factors and price factors while measuring the variables of the study.

The data were collected through a cross-sectional survey conducted in Lucknow and Indore, cities located in the northern India. Both cities represent emerging metropolitan areas and are educational and business hubs, attracting population from nearby cities and towns for education and employment. An identically structured questionnaire in the English language with pretested measures was used to collect data in both the cities. The survey method was commonly used in the related research (Alexandrov et al., 2013; Dodd et al., 2005; Goldsmith et al., 2012). Convenience sampling method was employed to solicit responses. Smartphone users are only 17% of the total Indian population (Live Mint, 2016). Moreover, in absence of a list of smartphone owners, it was difficult to get access to target respondents using random sampling method. Therefore, convenience sampling was deemed to be appropriate for this study. However, attempts were made to include respondents with varied demographics to reduce any bias. Therefore, face-to-face paper-based survey was conducted in different regions of both cities such as retail malls, university campuses, and corporate offices where it was easy to find smartphone owners. This method was used by previous researchers (Alexandrov et al., 2013; Donoghue et al., 2016). The researchers collected the data during different times of days to enhance the probability of including different consumers and to overcome the limitations of convenience sampling to some extent. The questionnaire included a declaration that the responses obtained from this study will only be used for academic purpose and participants can stop responding if they don’t want to disclose any personal information. The participation in the survey was voluntary, and no monetary incentive or gifts were offered to the respondents. In total, 270 responses were obtained from both cities, and finally, 259 were considered suitable for the final analysis, after removing incomplete questionnaires.

The sample consisted of 67% and 33% for males and females, respectively. The respondents were from a varied educational background, where 9% of respondents exhibited a higher secondary education, 26% were graduates, 25% were pursuing graduation, and 35% had a postgraduate degree, and the remaining respondents had doctoral or vocational degrees. In terms of income, the respondents were well distributed in different income groups. Approximately, 40% of the respondents had an income less than INR 600,000; 22% of respondents were in an income group of INR 600,000–900,000; and 36% had an income more than INR 900,000 (1 USD = 63.5 INR, Bloomberg.com January 2018). Furthermore, the sample population was well distributed in different age groups, where 11% of the respondents were of an age less than 21 years, 41% were in the age group of 21–30 years, 22% were in the age group of 31–40 years, and 25% in the age group of more than 41 years. The average age of respondents was 29 years, and the mean income of respondents was INR 650,000. All the respondents were smartphone owners. The sample reflects the population of the study as smartphone ownership is high among, men, higher income groups, and millennials (Live Mint, 2016). However, the sample was collected from only two cities in India and focussed towards the younger age group (Average age 29 years). The more representative sample could have been acquired if the survey was conducted in multiple cities however considering the vast geography of India, time and cost were major constraints. All demographic indicators were subject to the initial analysis, and age, gender, education, and income were included as control variables in the final analysis.

4 MEASURES AND ANALYSIS

Scales used in the previous literature, which are already tested by researchers in the similar context, were used to prepare the questionnaire. Information acquisition confidence and social outcome confidence were measured using the scale proposed by Bearden et al. (2001) and used by Clark et al. (2008). The scale for measuring subjective knowledge was adapted from Flynn and Goldsmith (1999). The scale for IS intention and ID intention was adapted from Richins, Bloch, and McQuarrie (1992), which was also used by Dholakia (2001). In this study, we measured ID, which represents the intention of consumers to share information regarding a specific product with his reference group (Dholakia, 2001; Kiel & Layton, 1981). We measured the intentions rather than the actual search and dissemination behaviours. Moreover, other researchers have used a similar approach (see Dholakia, 2001). The respondents specified their level of agreement and disagreement on a 7-point Likert scale, where 1 indicates “strongly disagree” and 7 indicates “strongly agree.”

A preliminary test was conducted with 10 consumers, who offered their comments to ensure the lucidity of questions and confirmed that the structure of the questionnaire was unambiguous. Few sentences were restructured to enhance the readability of the questionnaire. After a few minor modifications, the questionnaire was pretested on a convenience sample of 40 target respondents. Chronbach’s alpha coefficients for the scales ranged between 0.76 and 0.90 (Table 1). Structural equation modelling using maximum likelihood estimation was employed to test the measurement and structural models. A series of dependence relationship can be analysed in a single model using structural equation modelling. A variable can be analysed as both independent and dependent in a structural model. Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using a two-step structural model approach (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988; Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, 2012). The reliability and the validity of constructs were assessed using composite reliability, average variance extracted, and discriminant validity. Further, the measurement model was first tested for an adequate fit. Finally, the structural model was tested for the adequate fit, and parameter estimates were used to test the proposed hypotheses. Further, the mediation hypotheses were tested using the Preacher and Hayes (2008) method by computing bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 and Analysis of Moment Structures version 16 software packages were used to analyse the data.

| Item wise constructs | Standardized loading | Average variance extracted | Composite reliability | Cronbach’s alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social outcome confidence | 0.526 | 0.766 | 0.763 | |

| 1. I impress people with the purchases I make | 0.609 | |||

| 2. My neighbours admire my decorating ability | 0.646 | |||

| 3. I get compliments from others on my purchase decisions | 0.688 | |||

| Information acqu isi tion confidence | 0.589 | 0.877 | 0.881 | |

| 1. I know where to find the information I need prior to buying a Smartphone | 0.679 | |||

| 2. I know where to look to find the product information I need about Smartphone | 0.671 | |||

| 3. I am confident in my ability to research important purchases of Smartphone | 0.867 | |||

| 4. I know the right questions to ask when shopping for Smartphone | 0.766 | |||

| 5. I have the skills required to obtain needed information before buying a Smartphone | 0.815 | |||

| Subjective knowledge | 0.581 | 0.845 | 0.843 | |

| 1. Compared to others you know, how knowledgeable are you about different types of smartphones? | 0.879 | |||

| 2. I do not feel very knowledgeable about smartphones. | 0.561 | |||

| 3. Compared to my friends, I am one of the experts on smartphones. | 0.771 | |||

| 4. I know pretty much about smartphones. | 0.854 | |||

| IS intention | 0.829 | 0.906 | 0.899 | |

| 1. Before buying the smartphone i would obtain substantial information about the different makes and models of smartphones | 0.830 | |||

| 2. I would acquire a great deal of information about the different makes and models before buying the smartphone | 0.983 | |||

| ID intention | 0.650 | 0.787 | 0.785 | |

| 3. I would give other people advice about buying a particular make and model of a smartphone | 0.868 | |||

| 4. I would like to influence my friends in their choice of particular make and models of smartphones | 0.737 |

5 FINDINGS

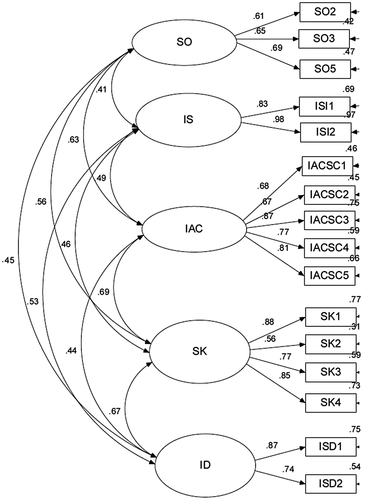

The confirmatory factor analysis indicated a satisfactory fit for the measurement model with a chi-square value of 204.661 (p < 0.001) at 89 degrees of freedom. The significance is not a crucial parameter because it is prone to a large sample size (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). The other fit measures were assessed, which indicated a satisfactory fit; GFI = 0.912, RMSEA = 0.071, CFI = 0.949, TLI = 0.931, and IFI = 0.950, indicating that the model adequately fit the data (Figure 2).

Construct validity, was assessed by ensuring convergent and discriminant validity. All standardized loadings were significant as required for convergent validity (Table 1). All loadings were more than 0.50, and most items fulfilled the 0.70-factor loading requirement (Hair et al., 2012). Furthermore, we assessed the average variance extracted, which exceeded the recommended criterion of 0.50 (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988).

The composite reliability of each construct was more than 0.70 (Hair et al., 2012) (Table 1). Furthermore, the discriminant validity of constructs was assessed by verifying that each latent construct extracted more variance from its indicators than it shared with all other constructs (Table 2). The variance-extracted value was greater than the correlation estimates ensuring discriminant validity.

| MSV | IS | SK | ID | IAC | SO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS | 0.279 | (0.911)a | ||||

| SK | 0.480 | 0.462(b) | (0.762) | |||

| ID | 0.477 | 0.528 | 0.691 | (0.806) | ||

| IAC | 0.480 | 0.490 | 0.693 | 0.440 | (0.768) | |

| SO | 0.280 | 0.369 | 0.516 | 0.406 | 0.529 | (0.726) |

Note

- SO = social outcome confidence, IS = information search intention, IAC = information acquisition confidence, SK = subjective knowledge, ID = information dissemination intention, MSV = maximum shared variance.

- a = Square root of average variance extracted.

- b = Correlations among the constructs.

After assessing the fit of the measurement model, the fit of the structural model was tested using the maximum likelihood estimate and the observed covariance matrix. The chi-square value is significant (Chi square 286.4, p = 0.000, df = 150), because it is prone to the sample size (Kline, 2005). We assessed other fit indices. The fit indices are GFI = 0.905, NFI = 0.886, IFI = 0.942, TLI = 0.926, CFI = 0.941, and RMSEA = 0.059. The values indicate the adequate fit of the structural model. The parameter estimates for hypothesis testing are mentioned in Table 3. As predicted information acquisition confidence was positively related to subjective knowledge, (path estimate = 0.617; p value = 0.000) supporting the first hypothesis. This relation implied that consumers who are confident in their ability to search for information also consider themselves to be knowledgeable regarding the smartphones. Moreover, the second hypothesis, which indicated that information acquisition confidence positively affects the IS intention, was also supported (path estimate = 0.315, p value = 0.001).

| Hypothesized relationships | Estimates | CR | Sig. (p < 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information acquisition confidence → subjective knowledge | 0.617 | 7.587 | 0.000 |

| Information acquisition confidence → IS intention | 0.315 | 3.284 | 0.001 |

| Social outcome confidence → subjective knowledge | 0.159 | 2.326 | 0.020 |

| Social outcome confidence → ID intention | 0.082 | 1.147 | 0.251 |

| Subjective knowledge → IS intention | 0.262 | 2.817 | 0.005 |

| Subjective knowledge → ID intention | 0.661 | 7.790 | 0.000 |

The social outcome confidence of consumers is positively related to subjective knowledge, (path estimate = 0.159, p value = 0.020) supporting the third hypothesis. This relation means that consumers who are confident that they can make socially acceptable decisions are likely to have high subjective knowledge. An insignificant direct relationship existed between social outcome confidence and the ID intention (path estimate = 0.082, p value = 0.251). Subjective knowledge is positively related to the IS intention, (Path estimate = 0.262, p value = 0.005). Similarly, subjective knowledge is positively related to dissemination intention, (path estimate = 0.661, p value = 0.000). The results indicate that if subjective knowledge is high, consumers will have high propensity for information search and dissemination.

To test the fifth and sixth hypotheses related to mediation, we used the method suggested by Preacher et al. (2008). To estimate the standard error of the subjective knowledge mediator on the relation between social outcome confidence and the ID intention, we computed bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals (Table 4). The indirect effect was significant, and 95% confidence interval did not include zero (Lower bound = 0.004 and Upper bound = 0.335, p < 0.05). The direct effect without the mediator became insignificant when the mediator was introduced. This transformation indicated that subjective knowledge fully mediated the relation between social outcome confidence and the ID intention, supporting the fifth hypothesis.

| Relationship | Direct effect without mediator (Sig.) | Direct effect with mediator (Sig.) | Indirect effect (Sig.) | Bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social outcome confidence → subjective knowledge → ID intention | 0.439 (Sig.) | 0.082(NS) | 0.105(Sig.) at p < 0.05 (95% CI) | 0.004 lower bound to 0.335 upper bound |

| Information acquisition confidence → subjective knowledge → IS intention | 0.506 (Sig.) | 0.315 (Sig.) | 0.162(Sig.) at p < 0.05 (95% CI) | 0.021 lower bound to 0.389 upper bound |

Similarly, for testing the sixth hypothesis, the results of the bootstrapping suggested that 95% confidence interval does not include zero for the mediation relation among information acquisition confidence, subjective knowledge, and the IS intention. The indirect effect was significant (Lower bound = 0.021 and Upper bound = 0.389, p < 0.05). The direct effect without the mediator was reduced but was significant when the mediator was introduced in the model indicating partial mediation, which supported the sixth hypothesis.

6 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This study aimed to investigate the influence of consumer self-confidence on the prepurchase search and information sharing behaviour, and the mediating role of subjective knowledge. The responses obtained from smartphone owners in India were analysed using structural equation modelling.

We found that information acquisition confidence positively influenced the IS intention, and subjective knowledge partially mediated this relationship. Consumers with high information acquisition confidence develop subjective knowledge leading to a positive IS intention. Because consumers with high subjective knowledge prefer impersonal sources of information (Barber et al., 2009; Dodd et al., 2005), enhancing the subjective knowledge can motivate consumers to refer marketer-dominated information sources, which facilitate the effective delivery of marketing communications. Moreover, the enhancement of subjective knowledge will fetch two-fold results for practitioners because expert consumers are expected to share information; another substantial conclusion from this study.

We found that the social outcome confidence of consumers was completely mediated by subjective knowledge and consequently, has a strong positive relationship with the ID intention. Thus, we add to the existing literature (Clark et al., 2008; Paridon, 2006; Wien & Olsen, 2017) by indicating that consumers, who are confident that their reference group will appreciate their purchase decisions, are more likely to offer advice and influence their friends in buying a particular product. This situation occurs because consumers with high subjective knowledge consider themselves experts and feel that they possess more product knowledge than their friends. Receiving positive comments regarding their purchase decisions enhances their subjective knowledge perceptions and consequently, motivates them to share information regarding the product. Thus, we also add to the findings of Alexandrov et al. (2013) who construed word-of-mouth behaviour as a result of social interaction process and found that consumers share word of mouth due to social and self-motives.

This study makes the following contributions to the existing literature: First, our results offer a new dimension to the existing knowledge by establishing that subjective knowledge is crucial for strengthening the relationship between social outcome confidence and ID. A consumer may be confident regarding the decisions that generate positive social outcomes; however, they also need to have knowledge about the product to influence their friends by offering advice and information on buying products. The increase in subjective knowledge can be important in enhancing consumer propensity to disseminate information (Donoghue et al., 2016; Yuan et al., 2016). We explain how social outcome confidence is an antecedent and generates positive subjective knowledge, thereby motivating consumers to share information. We expect this study to motivate researchers to consider social outcome confidence and subjective knowledge as key variables in studies related to the market mavens, word-of-mouth production, and opinion leader behaviour especially when conceptualizing such behaviour as a social interaction process (Alexandrov et al., 2013).

Second, we elaborate the mechanism through which information acquisition confidence can generate the positive IS intention, an issue that exhibited equivocal results (Loibl et al., 2009; Utkarsh, 2017). We suggest that consumers, who are confident in their information acquisition capabilities, develop higher subjective knowledge and consequently, have a higher intention to search for information. However, this does not mean that consumers will also exert high effort when searching for information. The existing research indicates that consumers with better subjective knowledge perform efficient pre-purchase search and thereby significantly reduce the search effort. They may evaluate products based on a few specific important attributes and consult few relevant sources (Moorman et al., 2004). Thus, we suggest that the relationship between consumer self-confidence and IS can be influenced by other mediating variables such as subjective knowledge, which can explain the inconsistencies observed in the previous research (Loibl et al., 2009; Utkarsh, 2017). In addition, we add to the findings of Jürgensen and Guesalaga (2018) by finding that self-confidence is a key variable not only influencing consumer innovativeness but also consumer’s knowledge assessment and IS behaviour.

Third, the results should also be seen in the context of the Indian culture. India is a collectivist country, where people particularly emphasize on social relations and bonding. Literature indicates that in a collectivist culture, consumers are more prone to sharing information with their close reference groups (Lam et al., 2009). Moreover, given the market scenario where a variety of smartphones exist and ownership growing at fast pace, first-time buyers will seek information from their peers, therefore the results of the study are more valuable for emerging markets like India. However, the study was conducted in only two cities of India and we did not obtain data on cultural dimensions. India is vast geography with different culture and values. The sample represents younger and slightly highly educated respondents as compared to the general Indian population. A sample with more varied demographics will be helpful in validating the results of the study.

Overall, this research extends the theoretical understanding of consumer self-confidence, subjective knowledge, and its influence on IS and ID. We add to the existing literature of how consumer self-confidence is related to consumer IS and ID behaviours, and the role of subjective knowledge (Clark & Goldsmith, 2005; Loibl et al., 2009; Mowen et al., 2007; Paridon, 2006; Wien & Olsen, 2017; Yuan et al., 2016). Furthermore, the study will help practitioners in understanding the differential effects of specific dimensions of consumer self-confidence on the propensity of consumers for searching and disseminating information in emerging economies.

7 IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY

The results from this study are highly relevant for firms designing marketing communication programmes and planning to accelerate the sharing of information by consumers. First, the results regarding IS suggest that firms should attempt to identify the consumers with high confidence in acquiring information and provide the detailed information through various sources. Moreover, this contributes to the enhancement of subjective knowledge. Because the previous research has indicated that consumers with high subjective knowledge prefer marketer-controlled information sources, providing detailed information that facilitates decision making is crucial.

Second, consumers with high social outcome confidence exhibit higher subjective knowledge perceptions and are motivated to share information with peers. To accelerate information sharing, managers should identify consumers who value social recognition and target them through marketing communication (Alexandrov et al., 2013). The communication should attempt to make them realize that their peers appreciate them and consider them as experts. This will facilitate and reinforce their subjective knowledge, consequently, the possibility of consumers sharing information may increase.

The findings are also valuable for online marketers. Firms can target consumers with high social outcome confidence and assign them as influencers and experts in online communities. This will further enhance their confidence and subjective knowledge. Moreover, the latest information can be shared with such consumers before the formal product launches to enhance their subjective knowledge. Thus, consumers will be highly motivated to share the information with their peers (Yuan et al., 2016).

8 FUTURE RESEARCH AND LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

Although the research offers several insights, this study exhibits few limitations. First, this study uses only two dimensions of consumer self-confidence, and therefore future research should attempt to include more dimensions such as personal outcome confidence, persuasion knowledge, and marketplace interface (Bearden et al., 2001) which could influence search and dissemination behaviour. Second, the data were collected from two cities using convenience sampling; India exhibits a vast geography that spreads over more than 25 states. Though we have made efforts to obtain a representative sample, yet samples from different regions of India will help in obtaining more robust results. Third, the relationship between the constructs has been tested using one product. Smartphone penetration is increasing at a fast pace in India representing a unique market scenario, therefore it would be worthy to test this model in other markets which are culturally different and also in the context of other products.

For future research, researchers should consider including other individual factors that influence the prepurchase search and dissemination. This research can be extended by conducting an experimental study, where the confidence level or subjective knowledge of the respondents can be manipulated to get more robust results related to the relationship examined in this study. Moreover, the future research can attempt to investigate the variables in the context of high technology products or luxury products. Furthermore, future researchers can attempt to examine the effect of subjective knowledge and consumer self-confidence on other factors related to the consumer behaviour such as the evaluation of products, post-purchase dissonance, and consumer well-being.