Introduction and practical approach to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency for the practicing clinician

Summary

Aims

In exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI), the quantity and/or activity of pancreatic digestive enzymes are below the levels required for normal digestion, leading to maldigestion and malabsorption. Diagnosis of EPI is often challenging because the characteristic signs and symptoms overlap with those of other gastrointestinal conditions. Additionally, there is no single convenient, or specific diagnostic test for EPI. The aim of this review is to provide a framework for differential diagnosis of EPI vs other malabsorptive conditions.

Methods

This is a non-systematic narrative review summarising information pertaining to the aetiology, diagnosis and management of EPI.

Results

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency may be caused by pancreatic disorders, including chronic pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis, pancreatic resection and pancreatic cancer. EPI may also result from extra-pancreatic conditions, including coeliac disease, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome and gastric surgery. Timely and accurate diagnosis of EPI is important, as delays in treatment prolong maldigestion and malabsorption, with potentially serious consequences for malnutrition, overall health and quality of life. Symptoms of EPI are non-specific; therefore, a high index of clinical suspicion is required to make a correct diagnosis.

Review criteria

- This narrative review summarises information pertaining to the aetiology, diagnosis and management of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) based on a search of the PubMed database supplemented with additional information from the authors’ personal knowledge and clinical experience.

Message for the clinic

- Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency results from pancreatic disorders and extra-pancreatic conditions. EPI results in vitamin deficiencies, weight loss, malnutrition and associated sequelae. Diagnosis of EPI is challenging because of non-specific signs and symptoms and lack of reliable diagnostic tests; therefore, a high index of clinical suspicion is required to make a correct diagnosis.

1 INTRODUCTION

Maldigestion and malabsorption of nutrients can be caused by many conditions that involve the digestive tract, including coeliac disease,1 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD),2 Zollinger-Ellison syndrome,3 small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)4 and alterations in the natural anatomy of the digestive tract.5 Another fundamental source of maldigestion and malabsorption is exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI).

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency is defined as a reduction in the quantity and/or activity of pancreatic enzymes to a level that is inadequate to maintain normal digestive processes.5, 6 The causes of EPI are numerous and are not necessarily limited to reduced levels of enzyme production. The condition also may stem from a relative reduction in functioning enzymes reaching the intestinal chyme mixture during digestion. This may result from pancreatic enzyme secretions being inhibited, inactivated by inappropriately low (acidic) pH and mixed poorly with food.6, 7

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency may initially present with non-specific symptoms, such as bloating, abdominal discomfort, steatorrhoea, diarrhoea, excess flatulence and weight loss, that are shared with other gastrointestinal conditions, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), coeliac disease, IBD and SIBO (Table 1).3, 6, 8-15

| Symptom | EPI | Coeliac disease | IBDa | SIBO | IBS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bloating | + | + | + | + | + |

| Abdominal discomfort/pain | + | + | + | + | + |

| Voluminous and foul-smelling stools | + | — | — | — | — |

| Steatorrhoea | + | + | — | + | — |

| Diarrhoea | + | + | + | + | + |

| Constipation | — | — | — | — | + |

| Abnormal stool frequency | + | + | + | + | + |

| Excess flatulence | + | — | — | + | + |

| Weight loss | + | + | + | + | — |

- EPI, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; SIBO, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth.

- a Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis.

The objective of this article is to increase awareness of EPI and its consequences and to provide a practical approach for the differential diagnosis of EPI vs other malabsorptive conditions for the primary care practitioner. Treatment of EPI and management of patients with the condition have been previously reviewed16-18 and are not described in depth here.

1.1 Prevalence of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency

The prevalence of EPI in the general population is unknown. However, the prevalence of EPI can be quite high among certain subgroups of individuals (Table 2), such as those with chronic pancreatitis (CP),9 cystic fibrosis (CF),19 pancreatic cancer20 and pancreas resection.21 EPI may also coexist with gastrointestinal conditions, including IBD, coeliac disease or IBS (Table 2).22-24 EPI may be particularly common whenever diarrhoea is present, whether with IBS (6%)22 or coeliac disease despite adopting a gluten-free diet (30%).25 The prevalence of EPI also appears to increase with age.26, 27 EPI may also occur in individuals with rare genetic diseases such as Shwachman-Diamond syndrome28 and Johanson-Blizzard syndrome.29

| Condition | Estimated prevalence |

|---|---|

| Chronic pancreatitis9 | 30% in patients with mild disease; 85% with severe disease |

| Cystic fibrosis19 | Approximately 85% of newborns |

| Diabetes68 | |

| Type 1 | 26%-44% |

| Type 2 | 12%-20% |

| HIV/AIDS14, 69 | 26%-45% |

| Intestinal disorders14, 23 | |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 4%-6% |

| Coeliac disease | 12%-30% |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 19%-30% |

| Inoperable pancreatic cancer20 | 50%-100% |

| Surgery21 | |

| Distal pancreatectomy | 19%-80% |

| Whipple surgery | 56%-98% |

| Shwachman-Diamond syndrome28 | 82% |

| Johanson-Blizzard syndrome29 | High |

1.2 Aetiology and pathology of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency

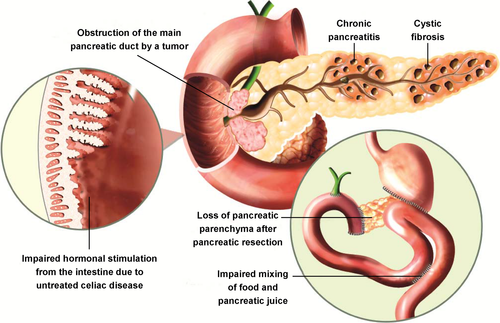

Most commonly, EPI stems from partial or total loss of pancreatic parenchyma because of CP, CF or pancreatic resection,6, 7 although many other aetiologies are possible (Figure 1). Physical obstruction of the pancreatic duct, as might be caused by a pancreatic tumour, can also result in EPI.20 Secretion of pancreatic enzymes may be impaired because of reduced neurohormonal stimulation (eg, in coeliac disease).14, 30, 31 by overproduction of gastric acid in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome6 or when acidic gastric chyme is inadequately neutralised if the pancreas does not appropriately produce or release bicarbonate.7 Mixing of gastric chyme with pancreatic enzymes in the duodenum can be rendered ineffective when anatomy is altered (eg, after gastric bypass surgery)7 or when the digestive process is unco-ordinated, resulting in postprandial dyskinesia. Less obvious conditions, such as oesophagectomy,32 IBS,22 type 1 diabetes,33, 34 and type 3c (“pancreatogenic”) diabetes secondary to CP or pancreatic cancer have also been associated with the development of exocrine dysfunction.35, 36 Diabetes may eventually lead to pancreatic dysfunction because of damage from microvascular pathology.37, 38

1.3 Importance of diagnosing exocrine pancreatic insufficiency

Symptoms and severity of EPI can vary widely from patient to patient.9 The typical symptoms of EPI (eg, bloating, abdominal discomfort, steatorrhoea, diarrhoea, excess flatulence, weight loss) are often found with other gastrointestinal conditions (Table 1). Thus, EPI may be missed in the differential diagnosis except in patients with “known” conditions that predispose to EPI, such as CP,39 CF,40 pancreatic resection21 or pancreatic cancer.20 This is unfortunate because delayed diagnosis of EPI may result in deleterious effects (Table 3). Furthermore, an underlying condition such as CP or a pancreatic malignancy may go unrecognised, with potentially significant long-term consequences.

| Continued symptoms |

| Bloating |

| Cramping |

| Diarrhoea |

| Weight loss |

| Negative impact on quality of life |

| Patients |

| Caregivers |

| Malabsorption leading to vitamin and micronutrient deficiencies |

| Vitamin D (decreased bone mineral density) |

| Vitamin A (visual impairment) |

| Vitamin E (neurologic changes) |

| Vitamin K (bleeding risks) |

| General malnutrition (poor growth in children; sarcopenia) |

| Malnutrition and its consequences for outcomes in different conditions |

| Chronic pancreatitis |

| Osteoporosis |

| Higher mortality |

| Pancreatic cancer |

| Lower survival |

| Pancreatectomy |

| More frequent infections |

| Longer hospital stays |

| Greater morbidity |

In individuals with EPI, clinically relevant maldigestion may occur earlier than overt symptoms (Table 3).9, 41, 42 Lipid-soluble vitamins are particularly affected5 because they are lost along with faecal fat. In patients with EPI, low levels of vitamin D can lead to osteoporosis. In patients with CP, the severity of EPI was significantly associated with lower bone mineral density as measured with dual-energy x-ray absorption and conventional x-ray measurement, which could underlie the high risk of fractures in patients with CP.43 Low levels of vitamin A can lead to visual impairment, especially in darkness.5 Decreased concentrations of vitamin E can cause neurological difficulties such as ataxia and peripheral neuropathy.5 A deficiency in vitamin K can lead to a higher risk of haemorrhage, which may manifest as ecchymoses.5 In children with CF, malabsorption of proteins and fat caused by untreated EPI is associated with poor growth.44 In adults with pancreatic diseases, EPI is strongly associated (P < .001) with muscle wasting.45 These consequences of EPI-related malnutrition can be further compounded if patients consciously choose to avoid certain foods, such as fatty items, that are likely to produce troublesome symptoms.46

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency is one of the factors that contributes to the malnutrition that is commonly present in patients with pancreatic cancer (Table 3).47 In one postoperative study, most patients with partial resection of the pancreas because of pancreatic cancer developed EPI at the earliest assessment (6 weeks), and a majority of patients continued to have EPI at months 3, 6 and 12.48 Malnutrition is a predictor of poor outcomes following surgery for pancreatic cancer.47 In an analysis of patients undergoing pancreatic resection for pancreatic cancer, patients at high risk for malnutrition had a fivefold higher surgical-site infection rate, a fourfold longer hospital stay and a higher overall morbidity rate than patients at low risk for malnutrition.49 Severe weight loss (ie, >8.4% of preoperative body mass) after resection of pancreatic cancer has been associated with significantly higher mortality compared with mild weight loss.50 In an analysis of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, more severe EPI was significantly associated with decreased survival.51 Conversely, in a different analysis, nutritional support was significantly and independently associated with longer survival in patients with pancreatic cancer, 63% of whom had symptomatic EPI.52

Malnutrition caused by EPI may also develop in patients with CP (Table 3).53 Patients with CP have increased risks of osteoporosis54 and mortality55 that may be related to malnutrition. Even subclinical EPI can result in malnutrition; in a small study of patients with coeliac disease, 4% of participants had EPI without symptoms but with nutritional deficits in serum samples.56

1.4 Differential diagnosis of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency

1.4.1 Approach to diagnosis of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency

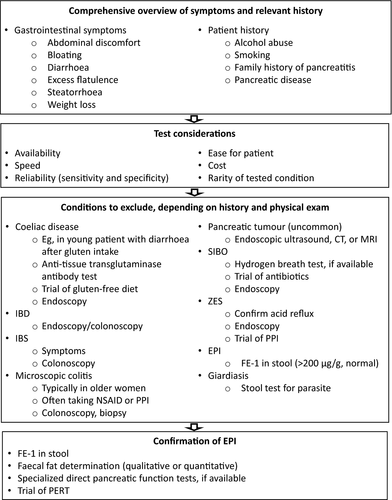

A general sequence for differential diagnosis of EPI is depicted in Figure 2. Investigation begins with a comprehensive overview of symptoms and obtaining relevant patient history; the results inform the most efficient sequence of subsequent investigations. Following that, a series of conditions are excluded based on patient history and results from physical examination, laboratory tests (eg, faecal elastase-1 [FE-1], faecal fat), imaging and trials of various conservative treatments. An empiric trial of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) may be performed, whether based on patient history and symptoms or on the results of laboratory tests. Finally, EPI may be confirmed through direct pancreatic function tests, if available.

1.4.2 Patient historical factors

The importance of a careful past medical, surgical, family and social history is paramount to elucidate the symptoms and guide investigations of potential EPI aetiologies and targets for therapy. When a patient presents with a history of persistent bloating, diarrhoea, fatty food intolerance and abdominal pain, suspicion of EPI ranks high among several possible diagnoses. A history of alcohol abuse and smoking may predispose to the gradual development of CP with associated EPI.57 Smoking is consistent with an increased likelihood of CP, pancreatic cancer and EPI; age may also increase the risk of EPI (≥60 years in a large association study of the general population in Germany).27 Steady weight loss could be consistent with maldigestion and malabsorption.46 However, because EPI can occur at any stage of life, it is possible that younger individuals and even those who are overweight or obese may develop EPI. A history of chronic alcohol and tobacco abuse should raise the possibility of underlying malignancy, particularly pancreatic cancer.58

1.4.3 Laboratory tests for diagnosis of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency

Traditionally, some clinicians may order testing for the presence of faecal fat.59 However, the absence of steatorrhoea is not unusual because even residual endogenous lipase production is sufficient to mask this symptom, or the patient may be avoiding fatty food because it provokes gastrointestinal symptoms.9, 44 The presence of gross steatorrhoea or positive qualitative faecal fat testing, although helpful for supporting the diagnosis of EPI, is not sensitive or specific for EPI.6, 14, 60 A quantitative determination of faecal fat is informative but requires the patient to eat a high-fat diet for 5 days or longer and collect all stool for the last 72 hours of the dietary regimen.9, 61 Inspection of stool for fat droplets is much simpler in all respects but provides only qualitative results that are subject to various interpretations.5, 9, 61 Neither kind of faecal fat determination is specific for EPI because other conditions can produce the same findings.9 Direct tests of pancreatic function based on stimulation of excretions by secretin and cholecystokinin have excellent performance but are conducted only in specialty centres, are invasive, and require a complicated procedure (even with the advent of endoscopy-based techniques) performed by skilled staff.9, 61

More recently, FE-1 testing has been considered for evaluation of EPI. FE-1 is an enzyme produced and released by the pancreas and remains intact during intestinal transit.6 It is highly sensitive and specific for detecting advanced EPI but is less reliable in milder cases of EPI, in patients following pancreatic resection, or in patients with watery diarrhoea.6, 14, 60 The patient should be counselled on proper collection of the sample to avoid spurious results (eg, because of sample dilution with diarrhoea), although this might not be critical,62 and the testing laboratory can remove excess water via centrifugation or lyophilisation.9, 63 Faecal chymotrypsin should not be used as a diagnostic test for EPI because it is less sensitive than FE-1.9, 60

1.5 Treatment and management of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency

The main goals of treatment of EPI are to relieve gastrointestinal symptoms and correct or improve the nutritional status of the patient.39 Because of the diverse causes and differing degrees of severity of EPI, treatment is highly individualised and often semi-empirical. Multiple professional guidelines and recommendations have addressed this topic,5, 15, 44, 64, 65 and several have been conveniently summarised.66 Certainly, patients with EPI who smoke or abuse alcohol should be counselled to quit.15 PERT is a cornerstone of the management of EPI; treatment is administered orally with meals and snacks at dosages that are adjusted to meet therapeutic goals.66 The success of a regimen is usually judged on the basis of achieving good nutritional outcomes while resolving any symptoms.66

1.6 Management of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency sequelae

After combining clinical symptoms and testing to make a diagnosis of EPI, there is still much work remaining in a team approach to care for the patient. This team consists of the primary care physician, gastroenterologist, nutritionist, endocrinologist and often pancreatic surgeons. Testing for overall nutritional status, fat-soluble vitamin levels and bone densitometry for evaluation of the presence of osteoporosis should be performed next. Fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies should be replaced appropriately.53 Testing and treatment for presence of diabetes type 3c and impaired glucose tolerance should be performed, given the increased risk of pancreatic endocrine dysfunction when pancreatic disease is present.67

2 CONCLUSIONS

In summary, EPI is a frequent source of malabsorption that presents as a syndrome characterised by broad symptoms of abdominal discomfort, bloating, flatulence, diarrhoea, weight loss and steatorrhoea (Table 4). These non-specific symptoms confound differential diagnosis because they overlap with those of several other gastrointestinal conditions. Timely diagnosis is important because untreated EPI may impair growth in children, lead to adverse outcomes of malnutrition and decreased overall survival, and impair quality of life. Successful diagnosis is made by carefully considering patient history, excluding other conditions with specific tests, and confirming the findings with therapy that resolves symptoms and improves outcomes.

| EPI causes maldigestion and malabsorption |

| Typical symptoms of EPI overlap with those of several common gastrointestinal diseases |

| Diagnosis of EPI may be challenging but achievable through a combination of objective testing, careful consideration of patient history and symptoms, and trial of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy |

| Delayed diagnosis of EPI may have significant negative consequences for a patient's health |

- EPI, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding was provided by AbbVie. Medical writing support was provided by Richard M. Edwards, PhD, and Michael J. Theisen, PhD, of Complete Publication Solutions, LLC, North Wales, PA, USA, which was funded by AbbVie.

DISCLOSURES

Mohamed O. Othman, AbbVie speakers bureau and research grant support. Consultant for Boston Scientific and Olympus America; Diala Harb, Employee of AbbVie and may own AbbVie stock and/or stock options; Jodie A. Barkin, AbbVie speakers bureau and educational grant support; Creon® (pancrelipase) is a product of AbbVie and is used in the treatment of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the interpretation of the collected literature and in the development of the content; all authors and AbbVie reviewed and approved the manuscript; and the authors maintained control over the final content.