Determinants and consequences of auditor-provided tax services: A systematic review of the international literature

Abstract

We review the empirical literature on the determinants and consequences of auditor-provided tax services (APTS) and provide some directions for future research. We first summarise two theoretical but competing perspectives on APTS provision, namely, the knowledge spillover effect and the impaired independence effect. We then review the evolution of APTS-related disclosures and regulations in selected jurisdictions. Our review of the determinants of APTS suggests that such decisions are related to the cost–benefit trade-off. We then review the literature on the consequences of APTS. This strand of the literature in the United States supports the knowledge spillover effect, but the findings in non-US settings are mixed. The market perceptions of APTS in both the US and non-US settings suggest that market participants react to APTS negatively during uncertain periods, whereas nonarchival studies suggest that the perceptions of APTS vary between stakeholder groups and with the types of APTS provided.

1 INTRODUCTION

We provide a systematic literature review on the determinants and consequences of auditor-provided tax services (hereafter APTS) in an international setting, critique the findings and offer suggestions for potential future research in this area.1 The well-known agency problem between shareholders and managers demands auditing services to provide independent assurance to corporate stakeholders that financial statements prepared by managers comply with generally accepted accounting principles (Agrawal & Chadha, 2005; Watts & Zimmerman, 1986). Therefore, auditor independence is the cornerstone of both audit quality and the auditing profession, as acknowledged by international regulators and practitioners. For instance, the International Ethics Standards Board for Accountants (IESBA, 2018) requires ‘… professional accountants in public practice be independent when performing audit or review engagements’ (Sec 400.1, p. 118).

IESBA (2018) explains two types of auditor independence: independence of mind and independence in appearance. Independence of mind is defined as ‘the state of mind that permits the expression of a conclusion without being affected by influences that compromise professional judgement, thereby allowing an individual to act with integrity, and exercise objectivity and professional skepticism.’ (Sec. 400.5a). Independence in appearance is defined as ‘the avoidance of facts and circumstances that are so significant that a reasonable and informed third party would be likely to conclude that a firm's or an audit or assurance team member's integrity, objectivity or professional skepticism has been compromised’ (Sec. 400.5b). The former is also known as independence in fact, and the latter as the stakeholders' perceptions of auditor independence. Academic research struggles to provide direct evidence on the former and, instead, uses various earnings quality proxies, for example, discretionary accruals, accounting restatements and earnings conservatism, to assess the presence or absence of such independence (e.g., Chung & Kallapur, 2003; Frankel et al., 2002). With respect to independence in appearance, archival research uses capital market-based measures to capture perceived audit independence such as the market valuation of accounting earnings (Francis & Ke, 2006; Ghosh et al., 2009; Krishnan et al., 2005). Since being independent is necessary to ensure high audit quality, we use ‘impaired independence’ and ‘low audit quality’ as interchangeable terms for the remainder of the paper.

In the past two decades, the increased proportion of revenues derived from providing nonaudit services (hereafter NAS) to audit clients has raised significant concerns since high NAS might increase economic bonding with clients and, hence, compromise auditor independence (e.g., Agrawal & Chadha, 2005; DeAngelo, 1981; Hermanson, 2009). This is also echoed by the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC, 2003), which points out that the joint provision of audit and NAS may reduce investors' confidence in auditor independence and in the public capital markets. On the other hand, the joint provision of audits and NAS may increase audit efficiency, as the client-specific knowledge acquired from providing NAS can be transferred to statutory audits, thereby enhancing auditors' effectiveness and efficiency in performing audits. (e.g., Joe & Vandervelde, 2007; Simunic, 1984).

In the meantime, the regulators noted that the beneficial versus the detrimental effects of NAS on audit quality depend on the types of NAS (SEC, 2003, 2014). In particular, the SEC (2002, 2003) describes APTS as services that ‘… traditionally have been viewed as closely related to audit services and as not being in conflict with an auditor's independence’, thereby financial statements users would view APTS more favourably than other types of NAS. As a result, in the aftermath of some regulatory reforms, the regulators in several jurisdictions, for example, the United States and the European Union (hereafter EU), decided to prohibit certain types of NAS but continued to allow auditors to provide APTS to their audit clients (EU Directive, 2006; EU Regulation, 2014; SEC, 2003, 2006). Consequently, APTS became the largest source of nonaudit revenues under the current environment in several jurisdictions (e.g., Alsadoun et al., 2018; Beasley et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2019; DeFond & Francis, 2005; Dobler, 2014; Francis, 2006). APTS could be further categorised into tax compliance and tax planning services. The former generally refers to preparing, signing and filing a tax return for the tax authorities, whereas the latter refers to a diverse range of services that could help clients manage tax affairs efficiently and find legitimate tax-saving opportunities. Therefore, firms' investment in tax planning services could generate substantial benefits (Mills et al., 1998) that tax compliance services cannot provide (Chyz et al., 2021). In some extreme cases, firms adopt tax positions, courtesy of APTS-induced tax planning, reducing their tax liabilities to zero. Naturally, tax planning services are more damaging than tax compliance services from the tax authority's point of view.

The empirical evidence, however, appears to be far less conclusive. The extant literature generally suggests that the simultaneous provision of audit and APTS by the same audit firm can result in either a ‘knowledge spillover benefit’ or a potential ‘impaired independence effect’ (e.g., Alsadoun et al., 2018; De Simone et al., 2015; Gleason & Mills, 2011; Kinney et al., 2004; Lisic, 2014; McGuire et al., 2012). The proponents argue that APTS facilitate the verification of tax-related accounts in financial statements by statutory auditors (e.g., Francis, 2006; McGuire et al., 2012; Seetharaman et al., 2011). Auditors evaluate the validity of accrued taxes payable and tax contingent liabilities on the balance sheet, income tax expenses on the income statement and the related note disclosures, in order to provide adequate assurance to the investing public about the appropriateness of these items and disclosures (Barrett, 2004). Managers can use valuation allowances (Frank & Rego, 2006), tax contingency reserves (Gupta et al., 2016), estimates of accrued taxes (Dhaliwal et al., 2004) and the designation of permanently reinvested earnings (Krull, 2004) to manage earnings. Material information about risky tax transactions tends to be hidden in these accounts and disclosures, thereby making proper auditing of tax accounts very difficult for external auditors.

Since client-specific knowledge is more likely to be shared within the same audit firm between the audit and tax departments (Gleason & Mills, 2011), the provision of APTS helps statutory auditors better understand clients' revenue-generating activities, revenue-recognition policies, accounting implications of (uncertain) tax positions and other tax-related activities, which could assist the auditors in planning strategies: especially the tax-related ones. Such knowledge sharing also benefits audit clients. For example, because of their better understanding of clients' operations and structures and their knowledge about the cutting-edge tax technologies, incumbent auditors have competitive positions over other external tax consultants as well as over clients' internal tax personnel, in reducing both taxes paid and tax expenses for financial statements (e.g., Maydew & Shackelford, 2007).2

Despite the potential benefits from knowledge spillover, the opponents of providing APTS argue that auditors may acquiesce or be perceived as having acquiesced to clients' aggressive accounting practices in order to retain lucrative tax services (e.g., Mishra et al., 2005). For instance, auditors might help clients manage earnings aggressively to avoid taxes (Alsadoun et al., 2018; Armstrong et al., 2012; Klassen et al., 2016). The regulators, too, have expressed concerns about APTS threatening auditor independence and have banned certain types of tax services that are more likely to impair auditor independence (SEC, 2006).3 Nevertheless, some audit firms continued to provide some APTS that have been banned by the SEC. For example, KPMG was charged by the SEC (2014) for the practice of loaning tax professionals to audit clients, which violated the rule prohibiting auditors from acting as an employee of clients. The SEC (2014) affirmed that auditors must assess the independence threats of providing certain types of NAS carefully, rather than just consider whether the proposed services fall within one of the permissible categories. These mixed results make our synthesis important not only to regulators but also to academic researchers.

We choose a systematic rather than a structured literature review. The advantage of systematic reviews lies in a ‘replicable, scientific and transparent process that enables the researcher to provide an audit trail, justifying his/her conclusions’ (Tranfield et al., 2003, p. 218). We adapt the Haapamäki and Sihvonen (2019) and Gepp et al. (2020) approaches to collecting papers for inclusion in this literature review, which combine both electronic and manual searches. First, we performed an extensive search via the Scopus database to identify potential studies published in accounting journals. Pany and Reckers (1983) report the first study that investigated the stakeholder's perception of APTS. Therefore, we restrict the journal library search to papers published between 1983 and April 2021, with a keywords search that includes ‘tax* service*’, ‘auditor-provided tax service*’, ‘APTS’, ‘tax NAS’, ‘NAS’, ‘nonaudit service*’, ‘nonaudit service*’, ‘nonaudit fee*’, ‘nonaudit fee*’, ‘NAS fee*’, ‘tax fee*’, ‘tax specialisation’, and ‘tax expertise’. We include APTS studies published in nonaccounting journals as well (e.g., Journal of Corporate Finance) to make the review comprehensive. To maintain the quality of this review, we include only those journals listed in the 2019 Australian Business Deans Council (ABDC) rankings.4

The search process generated 346 papers with proposed keywords from accounting journals. We then screened them manually to identify papers that examine either determinants or consequences of APTS by reviewing abstracts, hypotheses and empirical results sections, and by tracking down references in those papers. We performed the same methods to search for papers from nonaccounting journals. This screening process resulted in 101 papers published in business journals. To include the most recent research related to APTS, we also included some high-quality working papers. Similar to Harvey et al. (2016), we selected working papers (1) that have been presented at top conferences, (2) that have been cited one or more times by other published papers or (3) having at least one author in the author team who has published one or more papers on this topic, to maintain the quality of this review. This process yielded a total of 11 working papers.

Our final sample consists of 112 papers with an overwhelming majority of the papers examining the consequences of APTS and only 20 papers examining the determinants of APTS. Table 1 displays the journals' details and publication trends. As shown in Table 1, five journals, namely, The Accounting Review; Contemporary Accounting Research; Journal of Accounting, Auditing, & Finance; Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory and The Journal of the American Taxation Association; published more than 40% of the APTS research. A total of 41, 45 and 15 papers have been published in A*, A and B-ranked journals, respectively. We also observe that there has been a significant increase in the number of publications since 2006. Such a rapid increase in APTS research highlights the importance of our review.

| Panel A: Details of journals that published APTS studies | Rank | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Accounting Review | A* | 11 | 9.82 |

| Contemporary Accounting Research | A* | 10 | 8.93 |

| Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance | A | 9 | 8.04 |

| Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory | A* | 8 | 7.14 |

| The Journal of the American Taxation Association | A | 8 | 7.14 |

| International Journal of Auditing | A | 6 | 5.36 |

| Advances in Accounting | A | 5 | 4.46 |

| Managerial Auditing Journal | A | 5 | 4.46 |

| Journal of Accounting and Public Policy | A | 3 | 2.68 |

| Journal of Accounting Research | A* | 3 | 2.68 |

| Accounting and Business Research | A | 2 | 1.79 |

| European Accounting Review | A* | 2 | 1.79 |

| Journal of Accounting and Economics | A* | 2 | 1.79 |

| Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics | A | 2 | 1.79 |

| Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation | B | 2 | 1.79 |

| Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting | B | 2 | 1.79 |

| Review of Accounting and Fnance | B | 2 | 1.79 |

| Review of Accounting Studies | A* | 2 | 1.79 |

| The International Journal of Accounting | A | 2 | 1.79 |

| Accounting Horizons | A | 1 | 0.89 |

| Accounting Perspectives | B | 1 | 0.89 |

| Advances in Taxation | B | 1 | 0.89 |

| Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting & Economics | B | 1 | 0.89 |

| British Accounting Review | A* | 1 | 0.89 |

| International Journal of Accounting & Information Management | B | 1 | 0.89 |

| Journal of Applied Accounting Research | B | 1 | 0.89 |

| Journal of Business Finance & Accounting | A* | 1 | 0.89 |

| Journal of Business Research | A | 1 | 0.89 |

| Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance | B | 1 | 0.89 |

| Journal of Corporate Finance | A* | 1 | 0.89 |

| Meditari Accountancy Research | A | 1 | 0.89 |

| Pacific Accounting Review | B | 1 | 0.89 |

| Research in Accounting Regulation | B | 1 | 0.89 |

| Spanish Journal of Finance and Accounting | B | 1 | 0.89 |

| Total number of published papers | 101 | 90.17 | |

| Working papers | 11 | 9.83 | |

| Total | 112 | 100% |

| Panel B: Yearly distribution of APTS studies | ||

|---|---|---|

| N | % | |

| 1986–2005 | 10 | 8.93 |

| 2006–2010 | 14 | 12.5 |

| 2011–2015 | 37 | 33.04 |

| 2016–2020 | 36 | 32.14 |

| To April 2021 and In press | 15 | 13.39 |

| Total | 112 | 100.0% |

- Abbreviation: APTS, auditor-provided tax services.

Our study contributes to an understanding of the research findings in APTS and adds value to the series of Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) auditing synthesis papers (e.g., Carson et al., 2013; Knechel et al., 2013). First, although there remain several literature reviews and meta-analyses on NAS in general (e.g., Habib, 2012; Schneider et al., 2006; Sharma, 2014), no detailed review of studies relating to APTS, a significant component of NAS, exists. Our focus on APTS is duly justified as, compared with other types of NAS, APTS can affect the client's income and cash flows directly through tax rate reduction (e.g., Omer et al., 2006). The expertise possessed by auditors in both financial reporting and tax laws helps them design corporate tax planning activities that reduce the actual taxes paid (the cash flow effect) and, simultaneously, reduce tax expenses (the earnings effect) in the financial statements (Maydew & Shackelford, 2007). Also, APTS could be more closely related to audit work than other NAS (Francis, 2006; SEC, 2002, 2003), thereby generating knowledge spillover benefits. For example, when auditors perform financial statement audits, they need to review the clients' tax returns and reserves, a process that requires substantial knowledge about the audit clients (Sage & Sage, 2005). Auditors' tax expertise can enable them to understand clients' tax positions easily, thereby spilling the benefits over to financial statement audits.

Second, we use the knowledge spillover and the impairment of independence as the two opposing theoretical frameworks in organising this APTS-related review. Although the previous literature reviews and meta-analyses on NAS in general also used these two perspectives, we discuss these theories from both the accounting and tax reporting angles. For instance, when providing APTS to the audit clients across the fiscal year, the information sharing between audit and tax teams enables the incumbent auditors to be aware of material risky transactions having implications for tax reporting. Both the client- and industry-specific knowledge would help auditors design more effective and efficient audit and tax strategies, thereby generating substantial benefits to audit clients' financial and tax reporting, which are obviously not available for other types of NAS. On the other hand, owing to the significant and pervasive impacts of APTS on clients' accounting and tax reporting, the provision of APTS also raises serious concerns about auditor independence. Both the current and future lucrative revenues generated from providing APTS to audit clients may discourage auditors from providing high-quality audits (i.e., the self-interest threat). Also, the provision of APTS generally has significant impacts on tax accounts, which may lead auditors to end up auditing their own work (i.e., the self-review threat).

Finally, after banning most types of NAS in the United States and some other jurisdictions (e.g., EU), tax services became the most important and significant NAS that auditors could provide to their audit clients. However, ongoing debates on public firms' aggressive tax strategies and tax sheltering activities have attracted regulators' attention to the appropriateness of APTS (e.g., Harris, 2014). For instance, PwC was investigated by the US audit regulator because of advising its audit client, Caterpillar Inc., to avoid US $2.4 billion in taxes (Rapoport, 2014). Moreover, according to Klassen et al. (2016), more than 80% of audit clients purchased tax services unrelated to tax compliance from their incumbent auditors. In recent years, financial statement restatement issues related to ‘tax expense, benefit, deferral and other’ have surged in the United States (Audit Analytics, 2016; Sheridan, 2017), and income tax-related issues are one of the most cited deficiencies in the PCAOB inspection reports (Acito et al., 2018). Such findings raised significant concerns among regulators, practitioners and researchers as to whether the incumbent auditors can maintain their independence in an environment where APTS constitutes a significant source of audit firm revenue. Our review highlights whether such concerns are justified or not. In addition, Tepalagul and Lin (2015) suggest conducting more research related to NAS (including APTS) in non-US settings because of institutional differences that might lead to differences in incentives, perceptions and behaviour of the multiple stakeholders regarding the demand for, and supply of, APTS. Thus, the research findings generated from the United States may not be generalised to non-US settings. Although the bulk of the reviewed papers used data from the United States, there are some recent publications in other non-US settings, including Germany, Malaysia, South Korea and Spain, among others. Not surprisingly, we observe different findings across countries (or jurisdictions) for similar research questions. We hope that our systematic review will help stakeholders understand whether further regulations restricting APTS would be beneficial or not. We also hope that this review will be helpful for researchers willing to conduct additional research on the determinants and consequences of APTS in the United States as well as in non-US settings.

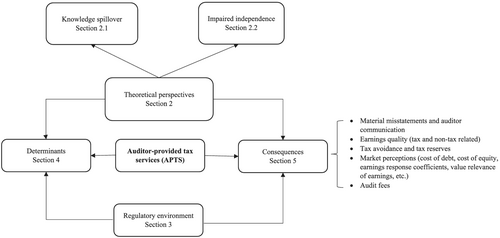

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 discusses the theoretical frameworks pertinent to the APTS literature. Section 3 provides an overview of the APTS regulations for selected jurisdictions. We review the literature that examines the determinants of APTS in Section 4. The consequences of APTS are reviewed in Section 5. Section 6 provides some useful directions for future research, and Section 7 concludes the paper. We present a framework underpinning our review of APTS in Figure 1.

2 THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES ON APTS

In this section, we introduce the main theoretical frameworks that are commonly used in APTS research. There are two competing views pertaining to the joint provision of audit services and APTS: the knowledge spillover effect and the impaired independence effect. The former argument contends that APTS can improve audit quality and reduce audit costs through sharing client-specific and industry-specific knowledge between tax and audit departments (De Simone et al., 2015; Gleason & Mills, 2011; Kinney et al., 2004; McGuire et al., 2012). The latter, on the other hand, suggests that auditors are more likely to or be perceived to compromise audit quality when they provide APTS to their audit clients, owing to the increased economic bonding between them (e.g., Alsadoun et al., 2018; Choudhary et al., 2021; Mishra et al., 2005). Therefore, prior studies suggest that the net effect of APTS on audit quality depends on which effect dominates (e.g., Choi et al., 2009; Fortin & Pittman, 2008; Krishnan et al., 2013; Lisic, 2014).

2.1 APTS and knowledge spillover arguments

The knowledge spillover effect assumes that the knowledge is transferable between different departments within an audit firm, and the audit and tax services require overlapping information pertinent to clients.5 Such information sharing is beneficial for several reasons. First, since APTS normally are performed across the fiscal year, the communication between tax and audit partners allows the audit team to be aware of material risky transactions at an early stage, thereby enabling the audit team to detect and remedy clients' internal control weaknesses (both tax and nontax related) before the release of the financial statements (De Simone et al., 2015). Second, prior studies find a strong and positive association between financial and tax reporting aggressiveness (Frank et al., 2009). When auditors provide tax services to their audit clients, auditors will gain good understandings of the client's tax strategies. Such understandings not only facilitate auditors attesting clients' tax-related assertions but also help auditors assess clients' attitudes towards financial reporting aggressiveness. Therefore, compared with auditors who only provide audit services (i.e., less informed auditors), auditors will likely design significantly different and more effective audit procedures when they provide both audit services and APTS to their clients (Joe & Vandervelde, 2007).

More importantly, when the incumbent auditors also provide APTS, audit personnel can learn and evaluate clients' uncertain tax positions easily: the knowledge that increases audit quality. On the contrary, if firms purchase tax services from parties other than the incumbent auditors, then the latter must first detect clients' uncertain tax positions and then obtain evidence of the outcomes of those positions. By using various measures of audit quality, the majority of empirical studies find a positive relationship between audit quality and APTS, indicating the existence of knowledge spillover effects (e.g., Kinney et al., 2004; Robinson, 2008). The extant literature also considers whether or not APTS are recurring in nature (e.g., Abdul Wahab et al., 2014; Paterson & Valencia, 2011). Recurring APTS are defined as tax services purchased from the same auditors for two or more consecutive years: otherwise, they are nonrecurring APTS. Recurring NAS gives rise to economies of scope, which would contribute to auditors' cost savings (e.g., Beck et al., 1988; Chung & Kallapur, 2003), especially for some categories of NAS (e.g., APTS) (Arruñada, 1999; Francis, 2006; Gleason & Mills, 2011). If auditors pass on the part of the cost savings to their audit clients, economic bonding between the two parties is declined, with a consequent positive effect on audit quality.

Moreover, the benefits of knowledge spillover effects are generated not only from client-specific knowledge but also from industry-specific knowledge obtained through providing tax services to firms in the same industry. McGuire et al. (2012) propose that auditors have superior knowledge of the industry-specific tax planning opportunities available to their clients if auditors are tax industry specialists. Such specialisation is also found to be helpful in establishing formal or informal benchmarks for reasonable accounting practices, and hence, auditors could detect and constrain industry-specific opportunistic earnings management behaviour (Christensen et al., 2015). Thus, tax industry specialisation could enhance not only tax service effectiveness but also audit quality. These benefits even exist when clients do not purchase APTS or purchase low levels of APTS from their incumbent auditors since the knowledge could spill over to different engagements across the same audit firm/office. However, Goldman et al. (2021) argue that the improved audit quality pertinent to income tax accounts is due to auditors possessing more general tax task-specific knowledge, rather than to industry expertise, since tax issues are not necessarily industry-specific (Hux et al., 2018). Goldman et al. (2021) find that audit offices with more general tax task-specific knowledge (proxied by audit offices' exposure to complex tax issues) decrease the incidence of tax-related restatements, whereas those with industry tax expertise exacerbate such restatements. Nevertheless, both Christensen et al. (2015) and Goldman et al. (2021) show that the benefits of industry tax expertise or general tax task-specific knowledge are concentrated in firms that procure low levels of APTS from incumbent auditors, indicating a substitution effect.

2.2 APTS and the impairment of independence arguments

In contrast to the possible benefits generated from the knowledge spillover effects, auditor independence can be, or be perceived as, negatively influenced by the joint provision of audit services and NAS, including APTS. The provision of APTS could create several threats to auditor independence, such as self-interest and self-review threats. Such independence threats will affect the independence of mind, independence in appearance or both. DeFond and Zhang (2014) suggest that the impairment of auditor independence could be triggered by both demand- and supply-side factors.

The first independence threat stemming from APTS is economic bonding (i.e., self-interest). Although the economic bonds between auditors and their clients are inherent even if auditors do not provide any NAS (DeAngelo, 1981), the provision of NAS increases the client-specific current and future quasi-rents, which increase the bond with and, in turn, the fee reliance on audit clients (Francis, 2006; Simunic, 1984). From the demand side, Srinidhi and Gul (2007) document that it is easier for audit clients to influence their auditors by including excessive rents in NAS fees, which are less regulated than audit fees. Since APTS is still permitted under the current environment in many jurisdictions, the purchase of APTS could be a way, or maybe the most important way, that audit clients can influence auditor independence. Also, from the supply side, owing to the pressure on auditors' (e.g., audit offices or partners) to achieve performance targets, their incentives to acquiesce to, or even help clients with, the manipulation of earnings and/or the adoption of aggressive tax positions increases as APTS fees increase (Alsadoun et al., 2018; Causholli et al., 2014; Doty, 2011; Favere-Marchesi, 2006). Therefore, audit clients that acquire both audit services and APTS gain more opportunities to conduct opportunistic behaviour than those purchasing audit services only, or other types of NAS, from their auditors. Besides the self-interest threat generated from current quasi-rents, Causholli et al. (2014) argue that ‘a client's promise of future NAS business has potential to impair an auditor's independence’ (p. 681). Supporting this argument, Lynch et al. (2021) find that auditors will receive about 17% more (5% fewer) APTS fees in the following year from their audit clients if they stop (start or continue) issuing tax-related key audit matters (KAM) to the clients in the current year. In sum, both current and future quasi-rents related to APTS fees can create enhanced economic bonding between auditors and audit clients, thereby threatening auditor independence.

The second independence threats stemming from APTS are the self-review concerns. Francis (2006) documents that the provision of NAS may change the auditor's role from outside independent reviewer to inside adviser and decision-maker. Since the provision of APTS is more closely and directly related to clients' income and cash flow (e.g., Maydew & Shackelford, 2007; Omer et al., 2006), auditors may end up auditing their own work. In such cases, auditors are less (more) likely to challenge (rely on) the clients' treatment of complicated tax issues and tax strategies that are advised by ‘auditors themselves’ (i.e., the tax services team in the same audit firm/office).

2.3 Section summary

In this section, we discussed two theoretical perspectives on APTS. The knowledge spillover effect suggests that the provision of APTS, especially the recurring ones, helps auditors to have a better understanding of clients' operations, internal control, tax strategies and of managers' attitudes towards financial reporting. Such understanding facilitates high-quality audits. The impaired independence effect suggests that the provision of APTS increases economic bonds between auditors and clients, thus decreasing their incentives to provide high-quality audits. The net effects of APTS, therefore, have been subject to a substantial amount of academic research over the years.

3 OVERVIEW OF THE APTS REGULATIONS FOR SELECTED JURISDICTIONS

In this section, we provide an overview of the APTS regulations related to both the disclosure of APTS and the provision of APTS by incumbent auditors. Leuz (2010) shows that the regulatory environment and institutional factors are different across countries, and these differences are likely to persist in the foreseeable future. Therefore, it is vital to understand differences in APTS regulations around the world, as they may affect both the determinants and consequences of APTS. The selection of jurisdictions is based on the importance of capital markets in the world economy.

3.1 United States

The SEC first issued Accounting Series Release (ASR) No. 250 in June 1978, which required firms to disclose the specific nature of NAS and total NAS as a percentage of total audit fees in their proxy statements (SEC, 1978). However, the SEC rescinded this requirement in August 1981. Parkash and Venable (1993) find that 90% of the Fortune 500 firm-year observations purchased APTS from 1978 to 1980. They also document that the demand for APTS varied with agency costs and auditor characteristics. Koh et al. (2013) use a similar dataset but do not find any evidence that the APTS fees ratio is related to impaired auditor independence. Subsequently, the SEC mandated the detailed disclosure of fees paid to registrants' auditors since 2001 to assist investors in evaluating the impact of the joint provision of audit and NAS on auditor independence. In particular, the SEC registrants must disclose their fees paid to auditors in three categories: (1) audit services fees, (2) financial information systems design and implementation (FISDI) services fees and (3) all other NAS fees (SEC, 2000). In addition, the SEC (2000) restricted certain types of NAS that would impair auditor independence when being provided by registrants' auditors, with some exceptions.

Following some accounting scandals, Section 201(a) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX) (hereafter, SOX, 2002) imposed stricter rules banning audit firms from simultaneously providing audit and FISDI services or some certain services classified in ‘other NAS’ (U.S. House of Representatives, 2002).6 However, SOX did not prohibit the provision of APTS, a category of NAS that auditors frequently provide to their clients (SEC, 2003). However, before acquiring APTS and other allowed NAS from their auditors, registrants must get pre-approval from their audit committees to assure stakeholders that providing such services will not impair the auditors' independence (Section 202 of SOX).

After SOX, the SEC (2003) amended the disclosure requirements for auditor fees. The new rules required registrants to disclose auditor fees in four separate categories: (1) audit fees, (2) audit-related fees, (3) tax fees and (4) all other fees. In regard to the addition of a ‘tax fees’ category, SEC stated that the provision of tax services needs extensive knowledge about the client, and the APTS fees are considerable in relation to other NAS fees. Therefore, SEC believes that it is appropriate and beneficial to investors if firms distinguish APTS fees from all other fee categories. The SEC (2003) rules became mandatory for years ending after 15 December 2003 and required registrants to provide such information for each of the two most recent fiscal years. As a result, registrants started to disclose the four categories of auditor fees information from 2002. Moreover, the SEC reiterated that audit firms could provide APTS (i.e., tax compliance, tax planning and tax advice) to their clients. However, some prior studies find that firms started to voluntarily dismiss, or substantially reduce, the purchase of APTS owing to concerns about the perception of impaired independence (e.g., Omer et al., 2006): a perception that imposed substantial costs on firms such as reduced tax savings (Cook et al., 2020) and low value relevance of earnings (Krishnan et al., 2013).

In 2005, the PCAOB further adopted three new rules prohibiting certain tax consulting services that are perceived to impede auditor independence. More precisely, Rule 3521 proscribed auditors from providing APTS with contingent fee arrangements, Rule 3522 prohibited auditors from promoting and providing clients with APTS for achieving aggressive tax positions to avoid tax and Rule 3523 banned auditors from providing any APTS to a person who has a role in financial reporting oversight (e.g., executives) at the client's firm or to immediate family members of such persons. On 19 April 2006, SEC (2006) approved these three PCAOB (2005) proposed rules, effective from 31 October 2006, and onward.

For new audit clients, PCAOB (2008) amended Rule 3523 to remove the restriction for tax services provided during the portion of the audit period that is completed before the beginning of the professional engagement period, since tax services provided in such a period are perceived not to impair auditor independence. The amendment of Rule 3523 would be effective immediately upon the SEC approval, which occurred on 22 August 2008 (SEC, 2008). Markelevich and Rosner (2013) find in their additional tests that APTS fees were positively associated with the likelihood of issuing fraudulent financial statements from 2000 to 2005. Also, Thornton and Shaub (2014) show that US jurors perceive a significantly lower audit quality when auditors provide audit clients with aggressive tax planning services, as compared with tax compliance services. These results support the new restrictions. Finley and Stekelberg (2016) document a significant decrease in tax avoidance for firms continuing to purchase APTS from Big 4 auditors from pre-2005 to post-2005 periods. However, Lennox (2016) examines the effects of these three new restrictions on audit quality and fails to find an increased audit quality, as proposed by the US regulators, after implementing new restrictions. Also, Nesbitt et al. (2020) show that despite complying with Rule 3522, audit firms have been advising larger clients on the use of more aggressive tax strategies increasingly over time. Moreover, some audit firms continued to provide some tax services that are not explicitly mentioned in the regulation but compromise auditor independence. For instance, KPMG was penalised 8.2 million US dollars by the SEC on 24 January 2014, for loaning tax professionals to audit clients from 2007 to 2011: a practice that violates the rule proscribing auditors from acting as an employee of clients. As a result, the SEC (2014) stated that auditors must carefully assess the independence threats of providing certain types of NAS, rather than just consider whether the proposed services fall within one of the permissible categories (e.g., tax services).

Overall, the regulatory environment of APTS in the United States consists of the following: (1) all APTS should be pre-approved by the clients' audit committee, (2) clients need to disclose APTS fees in their proxy statements separately, (3) auditors can provide only those APTS that would not jeopardise their independence and (4) SOX violations are subject to expanded criminal and civil liabilities and penalties.

3.2 EU

To make the relationships between auditors and audit clients more transparent, the EU Directive (2006) suggested and required disclosure of audit fees and the fees paid for NAS, including other assurance services, tax advisory services and other NAS in the notes of financial statements in all EU member states: requirements that are comparable with those of the US SEC (2003). In regard to auditor independence, the Directive also mentioned that auditors should not undertake any additional NAS that compromises their independence.

After the financial crisis around the world, regulators in the EU started to consider amending the audit regulations, including the prohibition of NAS, based on the presumption that NAS may compromise auditor independence as mentioned in the EU Directive (2006). According to the European Commission (EC, 2010) ‘Green Paper’, although there was no mandatory ban of NAS provision along with statutory audits in EU-wide regulations, some member states already implemented the EU Directive (2006), albeit in a very divergent manner. For instance, auditors are proscribed from providing any NAS to their audit clients in France, whereas the restrictions on NAS provision are relatively loose in other member states.

In the following year, EC (2011), Article 10, proposed a specific requirement prohibiting auditor-provided NAS in the public interest entities (PIEs). Specifically, the EC (2011) suggested banning or restricting auditors from providing services other than statutory audit services and related financial audit services to PIE audit clients. The scope of ‘related financial audit services’ includes (a) the audit or review of interim financial statements, (b) providing assurance on other statements (e.g., corporate governance, corporate social responsibility matters and regulatory reporting), (c) providing certification on compliance with tax requirements, where such attestation is required by national law and (d) other duty related to audit work imposed by the EU legislation on the statutory auditor. To enhance auditor independence, the EC (2010, 2011) even proposed banning auditors from providing any NAS to PIE clients and suggested that such prohibition might contribute to the establishment of ‘pure audit firms’, in which auditors could provide independent opinions without any business interest in their audit clients.

In 2014, Regulation (EU) No. 537/2014 amended and approved the EC (2011) proposal described above. The EU Regulation (2014) introduced a ‘blacklist’ of prohibited NAS across all EU member states. The first banned NAS in EU Regulation (2014), Article 5, is the APTS related to (i) preparation of tax forms; (ii) payroll tax; (iii) customs duties; (iv) identification of public subsidies and tax incentives; (v) support regarding tax inspections by tax authorities; (vi) calculation of direct and indirect tax and deferred tax and (vii) provision of tax advice. Other NAS included in the ‘blacklist’ are similar to those services that are banned in the United States (see Section 3.1 above). In addition, member states may further prohibit any NAS that they consider representing a threat to auditor independence. The EU Regulation (2014) also required a pre-approval from clients' audit committees if incumbent auditors want to provide some permissible NAS that is not part of the ‘blacklist’.

In addition, a fee cap was introduced on the total amount of fees to be charged for allowable NAS, assuming that the provision of NAS negatively affects auditor independence only when a certain threshold is exceeded. In particular, the total fees for those allowable NAS shall not exceed 70% of the average of the statutory audit fees in the last three consecutive fiscal years. Also, member states' regulators could opt to set stricter rules on the NAS fee cap. These new regulations were effective from 17 June 2016 onwards, and regulators expected to observe increased auditor independence after implementing those restrictions. Ratzinger-Sakel and Schönberger (2015) demonstrate that, although the EU Regulation has different impacts on the provision of NAS in different member states, the EU-wide regulation is an extension of existing restrictions in each member state. However, the new regulation seems unnecessary, considering the empirical findings in the EU, which show little impairment of independence due to APTS, using data from the pre-2016 regime (Castillo-Merino et al., 2020; Eilifsen et al., 2018; Garcia-Blandon et al., 2017, 2021; Watrin et al., 2019).

Notably, the EU Regulation (2014) provided a derogation option to member states when implementing these NAS regulations in their local legislations. That is, member states could opt to allow auditors to provide some valuation and certain tax services (i, iv, v, vi and vii contained in Article 5) that are included in the ‘blacklist’ if certain criteria are met.7 Therefore, EU regulators view some categories of APTS as less harmful to auditor independence than other NAS categories. According to the Audit Analytics (2020, December), most member states opted to allow the aforementioned tax services, and only eight member states decided not to use this option. In other words, APTS are totally banned in these eight member states (i.e., Croatia, Greece, France, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal and Slovenia). Regarding the fee cap on NAS, all member states have opted for the 70% except for Portugal where a 30% cap has opted. It is worth noting that there is no specific fee cap for APTS. Moreover, recent studies show that the mean or median APTS fees ratios are well below 20% or 30% in some EU countries, such as Spain (Castillo-Merino et al., 2020) and Germany (Eilifsen et al., 2018; Watrin et al., 2019). Although there are some firms with very high APTS fees, this fee cap regulation may have less or no influence on the purchase or provision of APTS for most of the listed firms in the EU.

The EU Regulation (2014) specified some tax services that should be banned without exemption, namely, (ii) and (iii) contained in Article 5, which seems to be different from the US regulation. However, although these services fall within the tax services category, providing these services would make auditors play either an accounting role or a management function role for the audit clients, posing serious threats to auditor independence. Therefore, this rule is, in general, consistent with the US SEC (2014) argument that auditors should assess both the nature and the manner of delivering some types of services to make sure auditor independence is not compromised, although EU Regulation (2014) is less ambiguous than the US regulation.

3.3 Other jurisdictions

Besides the regulatory environments in the United States and EU, which have received much attention in the previous literature, we also provide a brief review of regulations related to APTS in some other jurisdictions, based on the importance of their capital markets in the world economy. As the second-largest capital market, China mandated the disclosure of NAS fees in 2001, but there is no specific regulation related to APTS thus far. This seems reasonable because the Chinese NAS market is small, and most firms do not purchase NAS from their incumbent auditors (Chen et al., 2010; Fang et al., 2014). Thus, the provision of NAS, including APTS, is not considered to threaten auditor independence. Hong Kong has not mandated the disclosure of NAS fees yet, and therefore, it is difficult to determine whether the provision of such services is valued favourably by the stakeholders or not. However, Law (2010), using a survey among some Hong Kong auditors and financial analysts, finds that APTS are perceived as a value-added service by their clients by comparison with other types of NAS such as corporate finance services and internal audit services. Japanese auditors are banned from providing certain types of NAS, including any type of APTS. The Companies Act of 2013 in India prohibited certain types of NAS but did not prohibit APTS. If Indian listed firms purchase APTS from their incumbent auditors, they need to disclose the fees paid under ‘Payments to the auditors for taxation matters’ in their financial statements.

Although Canadian prohibitions of NAS are very similar to the US ones, there are some differences. The CPA Canada Independence Working Group (IWG) initiated a discussion in 2012 about whether to further prohibit certain types of APTS as the US SEC did in 2006 (IWG, 2012). In the following year, IWG (2013) concluded that it would support additional prohibitions of APTS with respect to personal tax services for individuals who hold financial reporting oversight roles (similar to US Rule 3523) and aggressive and confidential tax transactions (similar to US Rule 3522). IWG (2013) called for more studies on the impacts of the provision of APTS on a contingent basis (similar to US Rule 3521). So far, these suggestions have not been enforced in Canada. Moreover, CPA Canada (2016) clearly states that if auditors are already providing services related to ‘Tax calculations for the purpose of preparing accounting entries, except under certain circumstances in emergency situations [Rule 204.4 (34) (b)]’ for a listed firm, then they shall not perform audit services for that same firm. Makni et al. (2020) published the only study using Canadian data to explore the impacts of APTS and find weak evidence that the ratio of APTS fees to total auditor fees is positively associated with the firms' use of tax havens.

The Certified Public Accountant Act in South Korea mandated the disclosure of NAS fees and their components in 2001 and prohibited certain types of NAS in 2002, although such prohibitions were less restrictive compared with the United States and EU (Kang et al., 2019). The Korean National Assembly amended the Korean CPA Act on 18 February 2016 and banned additional NAS, making Korean law similar to the US SOX (2002). However, like India, South Korea has not banned any APTS because the Korean Institute of Certified Public Accountants (KICPA, 2006) suggests that the provision of APTS is unlikely to impair auditor independence. Empirical research supports this view (Choi et al., 2009). Taken together, our review of the APTS regulations reveals significant variations across jurisdictions. Table 2 provides an overview of APTS-related regulations in different jurisdictions.

| Jurisdictions | APTS (1) | APTS restriction (2) | APTS disclosure (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| China | Yes | No | No |

| European Union | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hong Kong | Yes | No | No |

| India | Yes | No | Yes |

| Japan | No | N/A | N/A |

| South Korea | Yes | No | Yes |

| United States | Yes | Yes | Yes |

- Note: In this table, we provide an overview of APTS-related regulations in different selected jurisdictions. For the purpose of this paper, we focus on the APTS provided to audit clients only. Column (1) shows whether auditors in a certain jurisdiction are allowed to provide tax services, and Column (2) indicates whether certain types of APTS are clearly banned in the same jurisdiction. In Column (1), ‘Yes’ means auditors are permitted to provide tax services to audit clients, and ‘No’ means auditors are prohibited from providing any types of tax services to audit clients. In Column (2), ‘Yes’ means there are additional restrictions on certain types of APTS; otherwise, it will show ‘No’. Conditional on the provision of APTS is permitted either fully or partially. Column (3) shows whether the audit clients need to disclose APTS fees in the financial statements.

- Abbreviation: APTS, auditor-provided tax services.

4 DETERMINANTS OF APTS

We review the literature investigating the determinants of purchasing tax services from incumbent auditors in this section. Four types of APTS-related decisions are reviewed, namely, decisions involving: (1) voluntary APTS information disclosure, (2) choice of incumbent auditors as tax service providers, (3) retention or dismissal of incumbent auditors as tax service providers, and (4) the magnitude of APTS fees.

4.1 Voluntary disclosure of APTS information

As discussed in Section 3, publicly listed firms were required to disclose the amount of APTS fees from 2003 in the United States (from 2006 in the EU countries), although some firms voluntarily disclosed the APTS information prior to the passage of these regulations. Omer et al. (2006) examine the factors associated with firms' decision to purchase APTS from 2000 to 2002. To control for potential selection bias resulting from purchase and disclosure decisions, they model the factors influencing such decisions in the first stage of the Heckman two-step estimation process. There are two findings from Omer et al.'s (2006) selection bias regressions. First, the decision to disclose APTS fees is positively associated with tax complexity, auditor tenure and auditor change and negatively associated with the proportion of NAS fees to total fees, thereby supporting the notion that firms tend to resist disclosing APTS fees information to reduce political costs associated with heightened regulatory scrutiny. Second, their results imply that firm size and auditor size jointly affect a client's decision to purchase APTS but not the decision to disclose APTS fees. Bedard et al. (2010) extend Omer et al. (2006) by including two important players in the corporate governance structure of a firm (i.e., the audit committee and the auditor) in explaining firm's voluntary APTS fees disclosure decisions. They confirm the negative association between APTS fees disclosure and the proportion of NAS fees to total fees. Importantly, the negative association is found to be more pronounced when firms have a strong audit committee: a finding inconsistent with the audit committee oversight theory. A stronger audit committee may perceive costs resulting from regulatory scrutiny as outweighing the additional benefits of disclosures to investors. Also, this negative association is stronger for firms audited by non-Big 4 auditors, which is consistent with the findings that clients of non-Big 4 auditors tend to disclose less information (e.g., Clarkson et al., 2003).

4.2 Selecting incumbent auditors as tax service providers

It is worthy of note that publicly listed firms are required to disclose only the tax services fees paid to their incumbent auditors but not if they purchase tax services from other providers or if their internal tax departments perform those services. Therefore, we could not find any empirical paper using publicly available data to examine the entire spectrum of tax services provider choices in publicly listed firms. However, using proprietary data from the US Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and focusing on tax compliance services only, Klassen et al. (2016) find that firms are more likely to hire incumbent auditors to prepare tax returns when they have been less tax aggressive in the past, higher-growing and smaller. Furthermore, firms having fewer foreign activities, incurring losses, engaging in R&D activities and exhibiting high other NAS fees ratios also tend to select incumbent auditors to prepare tax returns. Neuman et al. (2015) provide additional evidence using data from the US not-for-profit sector (NFPs), where the decision to choose a tax service provider is observable for all entities. They find that the NFPs are less likely to purchase tax services from the incumbent auditor as the distance between the firm and the auditor increases, indicating that tax services, similar to financial statement audit services, also require a high degree of client contact. Moreover, Neuman et al. (2015) posit and find that clients are more likely to hire other audit firms or law firms when the set of substitute service providers is greater and, thus, the purchase of tailored services is facilitated.

4.3 Retaining or dismissing incumbent auditors as tax service providers

Instead of examining the determinants of purchasing APTS directly, another stream of studies provides some evidence about the reasons audit clients decide to dismiss or retain their incumbent auditors as their tax services providers (Ahn et al., 2021; Albring et al., 2014; Finley & Stekelberg, 2016; Lassila et al., 2010). Because SOX (2002) and SEC (2000, 2003, 2006) prohibited certain types of NAS and required more granular classifications of fees disclosure, public firms substantially reduced or terminated the purchase of some NAS, including tax services, from their auditors, to reduce negative reactions from investors and regulators (Abbott et al., 2011; Finley & Stekelberg, 2016; Lennox, 2016; Maydew & Shackelford, 2007), even when the regulations clearly suggested that inv+estors would view APTS more favourably than other types of NAS (SEC, 2003). Omer et al. (2006) show that the sample median APTS fees declined from US$256,880 in 2000 to US$145,150 in 2002, and Cook et al. (2020) further find that approximately 21% of the firms in their sample period (i.e., 2002 to 2005) eliminated or significantly reduced the use of APTS. Among these firms, the median APTS fees dropped from US$326,446 to US$53,000. Therefore, firms' decisions to retain or dismiss incumbent auditors as tax services providers became an important research question.

Lassila et al. (2010) mention that ‘retaining or dismissing’ decisions appear to be a trade-off between the benefits generated from knowledge spillover and the costs related to impaired auditor independence of mind or in appearance. If benefits exceed costs, firms will retain or hire their auditors as tax services providers and, otherwise, dismiss them. Therefore, those factors that can either increase the benefits of knowledge spillover or decrease the costs of impaired auditor independence will contribute to the hiring and retaining decisions. Lassila et al. (2010) find a positive association between clients' corporate governance and the likelihood of retaining auditors as tax services providers in the period surrounding the SOX (i.e., 2001 to 2003). The association is consistent with the argument that strong corporate governance increases auditor oversight and decreases the likelihood of impaired auditor independence (e.g., Carcello & Neal, 2003). However, using a sample of the matched switch and nonswitch firms in the post-SOX period (i.e., 2003 to 2006), Albring et al. (2014) find a negative association between corporate governance attributes and the decision to retain auditors as tax services providers. Likewise, both Almaqoushi and Powell (2021) and Bédard and Paquette (2021) show that audit committee quality indices are negatively associated with the purchase and magnitude of APTS fees. These studies support the conservative behaviour of directors or audit committee members in response to the increased litigation and potential reputation risks after the passage of SOX. Furthermore, the ex-ante independence risk will increase the costs of retaining decisions. Both Ahn et al. (2021) and Lassila et al. (2010) posit and find evidence that auditors will be perceived as lacking independence if they provide high nontax NAS relative to audit fees to their audit clients and have a long relationship with them; consequently, the clients are less likely to retain incumbent auditors as tax services providers.

On the other hand, if some firm-specific characteristics increase the potential benefits through knowledge spillover effects, firms are more prone to retain the incumbent auditors as their tax service provider. Both Albring et al. (2014) and Lassila et al. (2010) find that firms are more likely to retain their auditors as tax services providers when they have high tax and operational complexity, supporting the notion that the complexity (e.g., the existence of foreign operations and the M&A activities) will generate more knowledge spillover benefits. Complexity also encourages firms to purchase more tax advice from incumbent auditors (Omer et al., 2006). Similarly, Bédard and Paquette (2021) find that the high ex-ante litigation risk of firms encourages audit committee members with accounting financial expertise to purchase more APTS. However, the moderating effects of firm litigation risk exist only in the period of 2007 to 2011 when the public scrutiny had faded away.

Finley and Stekelberg (2016) use a ‘natural experiment’ method to examine the impact on retaining decisions of external oversight imposed on tax service providers. Specifically, KPMG, one of the Big 4 firms, entered into a deferred prosecution agreement (DPA) with the US Justice Department in 2005 to resolve charges stemming from the sale of tax shelter services to its individual clients. KPMG agreed to comply permanently with several tax services rules that are stricter than those required of other tax services providers, which limited KMPG's ability to facilitate some tax avoidance strategies for clients.8 The authors investigate the reactions of firms that are currently purchasing APTS from KPMG in response to the potential damage to KPMG's reputation and/or the decreased expected tax benefits owing to the DPA. The results show that while all other Big 4 firms' provision of APTS declined in the post-DPA period, KPMG suffered more from the DPA than other firms, in terms of both the likelihood of purchasing APTS and the amount of purchased APTS. The authors also examine whether tax avoidance decreased significantly for the KPMG clients that decided to continue purchasing tax services from KPMG after the DPA, compared with clients of other Big 4 auditors. Surprisingly, KPMG's clients did not exhibit any difference in tax avoidance behaviour relative to clients of other Big 4 auditors. In addition, Baugh et al. (2019) find that the audit quality of KPMG did not change significantly relative to other Big 4 auditors after the DPA, even for KPMG clients that dropped KPMG as the tax service provider. Combining these two studies, we may conclude that the DPA had no or little effects on KPMG's audit and tax services quality.

Similarly, Ahn et al. (2021) examine the changes in APTS after the public disclosure of the 2007 PCAOB Part II inspection report, which identified Deloitte's deficiencies related to audits of income tax accounts. They find that, compared with other large audit firms inspected by the PCAOB, both the increased costs stemming from perceived impaired independence and the decreased benefits due to Deloitte's inability to use knowledge transferred from the tax team, prompted Deloitte's audit clients to dismiss or reduce the purchase of APTS from Deloitte. Overall, these results related to KPMG and Deloitte are supportive of Omer et al.'s (2006) finding that clients terminated or significantly reduced APTS investment around the uncertain external oversight environment.

4.4 The magnitude of APTS fees

Halperin and Lai (2015) develop a tax fee model from the clients' demand side to examine the determinants of APTS fees. In addition to unexpected audit fees (Omer et al., 2006), they find that expected audit fees are also positively associated with APTS fees, indicating a cross-selling behaviour of auditors.9 While Chan et al. (2012) find results similar to those of Halperin and Lai (2015), they do not develop a specific model for APTS fees. Other factors found to be associated with APTS fees are firm characteristics, executive and board characteristics (e.g., tenure, compensation, publicity, interlocks and alumni) and auditor characteristics (e.g., size, tenure and switch) (e.g., Alexander & Hay, 2013; Duan et al., 2018; Naiker et al., 2013; Omer et al., 2012; Parkash & Venable, 1993; Shi et al., 2021). Parkash and Venable (1993) find that firms with fewer agency costs (i.e., firms having high managerial ownership, high outside ownership concentration and low leverage), and firms having industry specialist auditors, tend to pay more APTS fees. Duan et al. (2018) utilise Google search volume to measure CEOs' publicity and find that firms whose CEOs have high publicity tend to avoid tax to meet investors' performance expectations. Importantly, such firms pay more fees for tax planning services to their incumbent auditors. Naiker et al. (2013) show that audit committees with former audit firm partners are less likely to purchase more tax services from firms' incumbent auditors, probably because of concerns over auditor independence. Regarding audit committee networks, Shi et al. (2021) find that purchases of APTS increase with the prior year's average of APTS purchased by board-interlocked firms via an audit committee board member. Omer et al. (2012) develop a composite measure to differentiate a group of firms having a new economy business model that ‘allows firms to exploit their operational flexibility to align with tax incentives’ and consequently reduce their tax burdens (p. 33). Therefore, if they follow the new economy business model, firms have less demand for tax planning services than their counterparts following the traditional business model.

Two more recent studies use a change specification to examine the determinants of APTS fees (Kim et al., in press; Lynch et al., 2021). Using the changes in APTS fees as the dependent variable, Lynch et al. (2021) find that auditors receive more APTS fees in the next year when they stop issuing tax-related KAM in clients' audit reports in the current year. Kim et al. (in press) explore the macroeconomic determinants of APTS fees. They argue that the benefits from investment in tax planning activities increase with an increase in optimism about future economic growth because firms expect to generate more pretax income and cash flows as well as more tax planning opportunities. Consequently, firms are likely to invest more in purchasing tax planning services. The authors find supportive results using US macroeconomic forecasts of real gross domestic growth (GDP) as a proxy for expected macroeconomic conditions. Moreover, this positive association is found to be more pronounced for firms with financial constraints and high tax rate volatility.

4.5 Section summary

In this subsection, we summarised prior studies examining four types of APTS-related firm decisions. Table 3 summarises the research questions, samples used and key findings of these papers. Although the papers examined different research questions, we can conclude that all of these decisions are related to a cost–benefit trade-off. If the expected benefits exceed the expected costs, firms are more likely to disclose APTS information, purchase or retain APTS and pay more fees for APTS. We will discuss the costs and benefits (i.e., the consequences) of APTS in the next section. However, the extant literature does find significant variations in the purchase of APTS based on firm-level and auditor-level characteristics, so it is crucial to control and correct selection bias induced by such factors before investigating the consequences of APTS.

| Authors (year) | Research questions | Sample | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Omer et al. (2006) | This paper examines the impact of uncertainty of external oversight on APTS. | United States: 5727 firm-years from 2000 to 2002, consisting of 2405 tax fees disclosers and 3322 nondisclosers. | Tax complexity, auditor tenure and auditor change are positively associated with voluntary disclosure of APTS fees, whereas the proportion of NAS fees to total fees is negatively related. Firm size and auditor size are positively associated with the likelihood of purchasing tax service from the incumbent auditors. |

| Unexpected audit fees are positively associated with APTS fees in 2000 and 2001, whereas this association is significantly weakened in 2002. From 2000 to 2001, new clients paid significantly greater APTS fees than continuing clients, whereas in 2002, shorter-tenure clients paid lower APTS fees. APTS fees are positively associated with reductions in the future tax rates (i.e., more tax avoidance) during 2000 and 2001. However, such benefits reduced or eliminated in 2002. | |||

| Bedard et al. (2010) | This paper examines the decision of firms to voluntarily disclose tax service fees paid to their incumbent auditors before the SEC (2003) regulation. | United States: 807 disclosing APTS firms and 225 nondisclosing firms in 2002. | Firms with a higher proportion of NAS fees to total fees are less likely to disclose APTS fees information voluntarily. This effect is exacerbated by strong audit committee governance and the use of a non-big 5/4 auditor. |

| Lassila et al. (2010) | This paper examines factors that influenced listed firms to retain or dismiss their incumbent auditors as tax services providers during the years surrounding the passage of SOX (2002). | United States: 1006 firm-years from 2001 to 2003. | Companies that experience relatively high tax or operational complexity, that have relatively strong corporate governance and whose auditors are relatively more independent are more likely to retain their auditors for tax services than companies that do not exhibit these characteristics. |

| Albring et al. (2014) | This paper examines the relations between audit committee quality, corporate governance and audit committees' decision to switch permissible tax services providers from incumbent auditors to others. | United States: 203 switch firms and 203 matched nonswitch firm from 2003 to 2006. | The switch decision increases with audit committee accounting financial expertise, board independence, institutional stockholdings, directors' stock ownership and CEO duality. Firms with a history of restatement/accounting irregularity, with higher tax to audit fees ratios and with unqualified audit opinions are more likely to switch. Larger, less leveraged firms, with higher stock returns, lower pretax accruals and firms accessing equity markets are also more likely to switch. The likelihood of switching is negatively associated with proxies for tax complexity, such as foreign operations and merger/acquisition activities. |

| Neuman et al. (2015) | This paper examines the determinants of tax services provider choice in the not-for-profit sector (NFPs). | United States: 4700 firm-years from 2004 to 2008. |

Greater distance (i.e., spherical distance in miles) between the client and the auditor increases the likelihood that NFPs hire nonauditor professional services firms or self-prepare the tax return. NFPs are more likely to hire nonauditor professional services firms as knowledge availability (i.e., the number of professionals employed in the local metropolitan statistical area) increases. Both external auditors and nonauditor tax service providers improved NFPs' disclosure quality pertaining to executive compensation and helped NFPs attract more donations in the following year. |

| Halperin and Lai (2015) | This paper examines the relation between APTS fees and audit fees after SOX from the perspective of cross-selling of services. | United States: 3545 firm-years from 2004 to 2008. | Audit fees are positively associated with APTS fees because of the cross-selling behaviour of auditors. Firm size, complexity, executive compensation, foreign operation, loss carry-forward, auditor size, the proportion of tangible assets and opportunity of tax avoidance are associated with APTS fees. |

| Finley and Stekelberg (2016) | This paper examines the effect of KPMG's deferred prosecution agreement (DPA) on the accounting firm ability to sell APTS and its clients' tax avoidance. | United States: 9787 firm-years with big 4 auditors from 2002 to 2008 (excluding 2005). | Firms are more (less) likely to terminate (engage) purchasing APTS from KPMG following the DPA. Among firms that continued engaging KPMG as their tax service providers, the amount of purchased APTS declines following the DPA, relative to the amounts for other big 4 clients. While there is a significant decrease in tax avoidance for firms continuing to purchase APTS from big 4 auditors from pre-2005 to post-2005 periods, KPMG's clients do not exhibit any difference in such behaviour relative to clients of other big 4 auditors. |

| Klassen et al. (2016) | This paper examines the large publicly traded firms' selection of tax preparers for tax compliance work. | United States: 1533 firm-years from 2008 and 2009 (804 firms in 2008 and 729 firms in 2009). |

Firms are more likely to prepare tax returns by internal tax staff when firms are more tax aggressive in the past, slower-growing, larger and have more foreign activities. Also, firms incurring losses, engaging in R&D and paying high other NAS fees are more likely to outsource tax compliance work to their auditors. Firms are more likely to hire incumbent auditors as tax return preparers rather than other external nonauditors when firms are less tax aggressive in the past, higher-growing, smaller and have high other NAS fees ratios. |

| Ahn et al. (2021) | This paper examines whether and how the public disclosure of the Deloitte 2007 PCAOB Part II inspection report related to income tax-specific quality control deficiencies affects its audit clients' retention of APTS. | United States: 9292 matched firm-years from 2009 to 2012 (4646 firm-years before and after 17 October 2011, respectively). | After publicly releasing the PCAOB part II report, the likelihood of using APTS among Deloitte's audit clients is 17% lower relative to audit clients of other annually inspected firms. Such effects are more evident among audit clients paying higher NAS fees and those with greater tax complexity but are mitigated among audit clients whose auditor possesses tax expertise. Among audit clients that retained Deloitte as the tax service provider, reliance on APTS decreased (i.e., they had lower APTS fees). |

| Almaqoushi and Powell (2021) | This paper examines the relationships between the quality of audit committee, financial reporting, internal control quality and firm value. | United States: 7054 firm-years from 2002 to 2012. | Firms with a low-quality audit committee tend to spend more expenditures on APTS. |

| Bédard and Paquette (2021) | This paper examines the effect of the presence of financial expertise on the audit committee on the purchase of APTS. | United States: 19,806 firm-years from 2003 to 2011. | Firms are less likely to purchase APTS and tend to pay less APTS fees when their audit committees have at least one accounting financial expert. Furthermore, this relationship is mitigated by the firms' ex-ante litigation risk, especially in the period of 2007 to 2011. |

| Kim et al. (in press) | This paper examines the effect of expected economic growth on the firms' investment in tax planning. | United States: 13,553 firm-years from 2003 to 2014. | Firms tend to invest more in tax planning activities (i.e., APTS fees) in periods when forecasted economic growth is more optimistic. Such association is stronger when firms are financially constrained and when firms are more likely to experience changes in tax status. |

- Note: All papers in this table are published papers with at least one hypothesis directly related to APTS.

- Abbreviation: APTS, auditor-provided tax services.

5 CONSEQUENCES OF APTS

In this section, we synthesise the empirical research examining the consequences of purchasing tax services from the incumbent auditors. We structure our review based on the different types of audit quality measures. Following DeFond and Zhang (2014) and Francis (2011), we classify our audit quality proxies into output- and input-based measures.

5.1 Output-based measures

5.1.1 Binary audit quality: Material misstatements and auditor communication

The first binary audit quality factor is the financial statement misstatement, the extent of which is measured by the restatements in subsequent periods. Christensen et al. (2016) reveal that both audit professionals and experienced investors view financial statement restatements as the most significant publicly available signal of low audit quality.

The Kinney et al. (2004) is one of the first papers linking the types of NAS with financial statement restatements before the SEC (2000; 2003) disclosure rules and the passage of the SOX (2002) restrictions on NAS. By using proprietary data from the years 1995 to 2000, the authors classify NAS into following five categories: (i) FISDI services, (ii) audit-related services, (iii) internal audit services, (iv) APTS and (v) other unspecified services. They find insignificant associations between FISDI, audit-related or internal audit services and the likelihood of restatement but find a significant negative association between APTS fees and restatement, especially for large firms. The results of Kinney et al. (2004) support the knowledge spillover benefits of providing APTS while supporting the impaired independence notion for the unspecified NAS. The insights gained from Kinney et al. (2004) also partially support the SOX ban on certain types of NAS while allowing APTS. Supporting this argument, Schmidt (2012) documents no relation between the levels of APTS fees and auditors' litigation risks following financial statement restatements. However, if auditors provide aggressive tax planning services to audit clients, US jurors tend to charge auditors high punitive damages when audit failure occurs (Thornton & Shaub, 2014). Beardsley et al. (2021) find that audit quality is lower (i.e., more restatements) among those audit offices that are more focused on providing NAS, suggesting a distraction effect of NAS on audit quality. However, this effect is driven by nontax NAS rather than APTS.

Following Kinney et al. (2004), the literature explored the possible moderators for the negative association between APTS and financial statement restatements, including the recurrence of APTS (Paterson & Valencia, 2011), types of restatements (Seetharaman et al., 2011), auditor size (Notbohm et al., 2015), institutional settings (Abdul Wahab et al., 2014; Castillo-Merino et al., 2020) and SEC (2006) restrictions on certain types of APTS (Lennox, 2016). Notbohm et al. (2015) report an auditor size effect incremental to the audit client size effect documented by Kinney et al. (2004). That is, if a client is audited by a small audit firm, the provision of tax services leads to fewer restatements regardless of client size, compared with clients audited by big audit firms. The authors give two possible reasons. First, large audit firms have ex-ante high audit quality regardless of APTS because they have more experienced employees and specialists (O'Keefe & Westort, 1992). Thus, small audit firms have more to gain from knowledge spillovers derived from providing APTS. Second, as small audit firms normally have fewer professionals to perform the audit and other NAS, knowledge spillovers may transfer easily between audit and tax professionals (e.g., Joe & Vandervelde, 2007).

Considering the types of APTS, Paterson and Valencia (2011) find that the negative association between APTS and future restatements only holds when the APTS are recurring in nature. On the contrary, firms purchasing nonrecurring APTS from their auditors incur more high-concern restatements: evidence supportive of impaired independence. Based on 953 firm-years from 2007 to 2009, Abdul Wahab et al. (2014) also document a negative relationship between recurring APTS and restatements in Malaysia, a market that has not experienced audit regulatory reforms like the SOX in the United States. However, the negative association holds only for a subgroup of firms with political connections. The authors, however, did not offer any explanation for this potentially interesting finding. Castillo-Merino et al. (2020) examine the association between future APTS fees and several audit quality measures including restatements in Spain. The authors find that neither current nor future APTS fees have any relationships with restatements. However, a positive (negative) relationship between current (future) APTS fees and the probability of issuing qualified opinions is documented by the authors.10