CEO compensation, corporate governance, and audit fees: Evidence from New Zealand

Abstract

New Zealand has continued to strengthen its financial reporting and auditing landscape after major corporate collapses highlighted audit failures contributing to investor losses. Jointly, investors have criticized exorbitant compensation paid to CEOs. While the PCAOB's (Public Company Accounting Oversight Board) emphasis on executive compensation has prompted several studies in the United States, this study is the first to examine executive compensation in the evolving setting of New Zealand. Specifically, we examine the incentive-based components of CEO compensation arrangements, finding both short-term incentive and stock option compensation to be significant and positively associated with audit fees. We also examine moderating effects of client governance factors and find evidence that internal governance (audit committee effectiveness, board resources, and board and audit committee diligence) moderates the association between short-term incentive and stock option compensation, and audit fees. Taken together, our evidence suggests that auditors consider CEO performance-linked compensation a risk factor and are pricing it into the financial statement audit, with client governance moderating this pricing effect.

1 INTRODUCTION

The role of executive compensation in the quality of financial reporting has received heightened global attention as several major accounting scandals have highlighted managerial incentives to manipulate earnings for personal financial gain. New Zealand has specifically undergone tremendous efforts to strengthen its financial reporting and assurance systems in light of numerous finance company collapses uncovering audit failure as a contributor to the size of investor losses (Davis & Hay, 2012). Simultaneously, shareholders of N.Z. public companies have become increasingly vocal in their skepticism of disproportionately high compensation paid to senior executives. Income equality projects such as “Closing the Gap” have emerged to address growing concern over extreme disparities between worker and CEO pay (Closing the Gap, 2018). Investors want evidence that CEOs do well financially only if investors do. Specifically, they are demanding CEO compensation that aligns with the interests of shareholders, and jointly criticizing the unclear and inconsistent transparency of compensation arrangements in corporate filings. They insist more detail would help alert them to indicators that a CEO may be motivated to act outside of the long-term interest of the company (Taylor, 2018). Since the corporate governance guidelines are not mandatory in New Zealand, which includes executive remuneration, it could explain why firms in New Zealand are not uniform in their reporting of executive remuneration. In this N.Z. setting of increased assurance and governance reform, coupled with greater shareholder interest in executive remuneration, our study examines how incentive-based executive compensation is considered by auditors and how corporate governance potentially influences this consideration, providing relevant, timely, and valuable evidence to policymakers, boards, and various stakeholders.

The International Federation of Accountants (IFAC), with ultimate jurisdiction over the international accounting and auditing standards employed in New Zealand, has specifically noted the need for greater oversight of executive compensation as it relates to firm risk management (IFAC, 2010). Additionally, the U.S.’s Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) has called for auditors to carefully and specifically evaluate client executive compensation practices in their audit considerations and processes. In its release, the PCAOB compels auditors to perform procedures to obtain an understanding of how “financial relationships and transactions that a company has with its executive officers, including executive compensation, perquisites, and other arrangements, can assist the auditor in identifying conditions (including incentives and pressures) that could result in risks of material misstatement, including fraud risks” (PCAOB, 2012, p. 87). These risk considerations continue to be highlighted in the board's updated risk assessment standards (PCAOB, 2018). Motivated by these pronouncements, several U.S. studies have emerged to empirically examine the relation between the sensitivity of stock options in executive compensation to stock returns (vega) and stock prices (delta), and audit fees. While this small body of research argues that auditors evaluate higher risks when there is greater sensitivity of executive stock option compensation to market-based performance measures, their results are mixed (Billings, Gao, & Jia, 2014; Chen, Gul, Veeraraghavan, & Zolotoy, 2015; Fargher, Jiang, & Yu, 2014; Kannan, Skantz, & Higgs, 2014; Kim, Li, & Li, 2015). However, these studies have not examined together the actual incentive-based components of CEO compensation that are enumerated in CEO contracts, which compensation committees approve and auditors evaluate for risk of financial misreporting. Vafeas and Waegelein (2007) do examine these components in a U.S. audit fee context, and conversely find evidence of a “substitution explanation.” They conclude that well-structured and incentivized compensation arrangements promote more effective managerial monitoring that substitutes for external auditor monitoring, thus decreasing audit fees.

The results of the U.S. studies cannot be generalized to New Zealand or many other countries, primarily because of differences in the size and nature of CEO compensation.1 With specific regard to New Zealand, Roberts (2015) reports the size of CEO pay in the United States averages $13 million to New Zealand’s $500,000. Further, CEO-to-employee pay ratios average more than four hundred times in the United States relative to the forty times in New Zealand. Additionally, CEOs are paid a lot more in equity in the United States (an average of 38% of total CEO pay), whereas equity compensation is quite limited in New Zealand (an average of 9% of total CEO pay). Also, the range of performance-based equity compensation widely used in the United States includes various types of stock options and stock awards, whereas in New Zealand most companies use cash bonuses as the primary performance-based compensation incentive (Roberts, 2015). Various stakeholders have criticized the lack of disclosure of stock option compensation and because of this opacity, it is not known if firms offer stock options to CEOs and choose not to disclose this, or if those disclosing are the ones offering stock option compensation (Taylor, 2018). Overall, this discussion suggests that it is not clear if auditors in New Zealand would consider the risk in CEO compensation as they do in the United States.

Finally, it is widely documented that the institutional, accounting, and auditing environments of New Zealand and many other countries and regions (e.g., Africa, Australia, China, Europe, Malaysia, Middle East, Singapore, South America) are different from the United States in numerous ways, including lower corporate and auditor litigation risk; smaller size and volume of capital markets (equity and debt); smaller size of firms; and less developed, more voluntary nature of governance regulations (Davis & Hay, 2012; Evans, 2004; Hay & Knechel, 2010; Knechel, Sharma, & Sharma, 2012; Redmayne & Laswad, 2013; Sharma, Sharma, & Ananthanarayanan, 2011). Additionally, legal and market penalties for auditor failures are much weaker in New Zealand, with a very small percentage of cases actually resulting in charges against the auditor (Sharma et al., 2011). Even after the Financial Markets Authority (FMA) in New Zealand began surveillance of audits in 2013 and discovered audit failures and collusion, our research of the FMA reports revealed that only six company directors have been sanctioned through a ban from serving in a management role, while auditors have not even been charged.2 From a research perspective, because the markets in New Zealand and in many other countries are thinly traded, and CEO compensation structure is different, tests based on vega and delta of CEO equity pay would not be meaningful in these countries, but the actual incentive-based components of CEO pay may be. Additionally, regulations on audit quality and CEO compensation in New Zealand and these countries differ from the United States. Thus, we specifically examine audit fee effects of short-term incentive and stock option compensation for N.Z. companies. Short-term incentive compensation is defined as remuneration linked to the short-term performance of the firm, including annual bonus, spot rewards, and/or retention bonus, and stock option compensation is represented by the existence of stock options in the CEO compensation package.

Furthermore, executive compensation packages are largely determined by firm governance mechanisms and the extent to which they are influenced by the CEO (e.g., Bebchuk & Fried, 2006; Bebchuk, Grinstein, & Peyer, 2010; Yermack, 1995, 2006). New Zealand has increasingly emphasized corporate governance since 2004, when the New Zealand Securities Commission distributed nine high-level principles to promote higher standards in corporate governance practices. Indeed, the N.Z. literature links several governance measures to CEO compensation and stresses the need for research to consider such relationships in the financial reporting and audit context (Cahan, Chua, & Nyamori, 2005; Reddy, Abidin, & You, 2015). There is an ample body of evidence showing the association between governance and the scope and extent of audit fees (see Hay, Knechel, & Wong, 2006 and Hay, 2013 for details). In settings similar to New Zealand, stronger governance has driven down auditor risk assessments, testing, and fees (Sharma, Boo, & Sharma, 2008; Tsui, Jaggi, & Gul, 2001), and in New Zealand, board and audit committee influence has been shown over the quality of financial reporting and the mitigation of threats to auditor independence (Knechel et al., 2012; Sharma et al., 2011; Sharma & Kuang, 2014). Recently, incentive-based audit committee compensation has been linked to lower accrual quality and abnormal audit fees, suggesting incentive-based compensation may lead to ineffective oversight from the governance mechanisms themselves (Lin, 2018). Taken together with executive compensation incentive studies emphasizing the need to consider the role of governance (Albrecht, Mauldin, & Newton, 2018), our study examines governance as a potential moderator of the relationship between N.Z. CEO short-term incentive and stock option compensation and audit fees.

We employ a sample of 810 N.Z. firm-years from 2004 to 2012 and examine how CEO short-term incentive and stock option compensation relate to audit fees. After controlling for the CEO's base salary, corporate governance factors, firm characteristics, auditor variables, and implementation of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), we find a significant positive association between both CEO short-term incentive (p < 0.01) and stock option (p < 0.05) compensation, and audit fees. Interestingly, when we introduce our governance analyses, we find that two governance constructs, audit committee effectiveness (p < 0.05) and board and audit committee diligence (p < 0.01), mitigate auditors' upward pricing of short-term incentive CEO compensation. This mitigation effect is likely due to the less complex nature of short-term incentive compensation as this comprises cash payments such as performance and retention bonuses, and spot rewards. Such incentive compensation elements are also likely to have more clearly defined performance linkages. However, the positive association between CEO stock option compensation and audit fees is more pronounced when the stronger board governance constructs are present. As stock option compensation is inherently more complex, involving judgments and assumptions, and disclosures are not required in New Zealand, information asymmetry effects may be motivating stronger boards to seek greater assurance from their auditors. Our results and inferences are robust to a multitude of additional analyses, alternative measures of our variables of interest, industry-adjusted measures of CEO compensation, and to potential endogeneity based on two-stage regressions and entropy-balancing analysis. Interestingly, we find that results relating primarily to stock options are more pronounced when clients operate in a more litigious industry. Such findings suggest that even in a country where overall institutional-level litigation risk is low, auditors consider risks in CEO compensation to be heightened for clients operating in relatively more litigious industries.

This study contributes to the literature and practice in several ways. First, our study is the first to expand the current U.S. CEO compensation and audit fee research to the N.Z. environment specifically, and to non-U.S. settings generally, with evidence suggesting that auditors are pricing client CEO compensation incentives even in smaller and more thinly traded non-U.S. markets. Our findings suggest that even with New Zealand’s lower litigation risk setting and differences in CEO compensation structure relative to the United States, auditors positively price CEO's short-term incentive compensation, regardless of whether the short-term incentives largely comprise cash bonuses or stock options. This finding suggests that auditors may be concerned about the risk of management manipulating short-term results to secure a bonus and other short-term compensation payouts. Second, we document that stronger client governance mitigates the association between CEO short-term cash incentive compensation and audit fees, but may increase audit fees when the incentive is stock option compensation. Accordingly, we extend the small body of CEO compensation-audit fee literature by documenting differential effects of corporate governance. Our moderating effect of governance provides a possible explanation of the inconsistent findings in the prior U.S. studies that have not examined how governance, a pivotal factor in financial reporting and assurance, influences auditor pricing of CEO's incentive compensation. Third, we inform N.Z. stakeholders of the relative importance of corporate governance measures in mitigating their concerns surrounding CEO compensation, with our results supporting arguments for greater corporate governance reform and disclosure in relation to CEO compensation, as the disclosures are currently very ambiguous. Fourth, our results also inform stakeholders and regulators in settings with audit and governance regulations similar to New Zealand as they make progress on their audit and governance reforms. The remainder of our article progresses as follows. The next section provides the background, review of prior literature, and hypotheses. We then present our research methods and discuss the results. Finally, we conclude the article.

2 BACKGROUND, LITERATURE, AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

2.1 New Zealand accounting and auditing environment

The N.Z. accounting and auditing environment has experienced significant changes as regulators have undergone a comprehensive review and reform of its financial reporting landscape. At the turn of the century, New Zealand had similar economic systems and auditing procedures to countries like the United States and Australia but lagged in reforms of the audit framework as regulators argued New Zealand does not experience financial scandals. In fact, New Zealand was one of the last countries with a self-regulating audit profession with reforms accelerating after major financial scandals rocked the nation (Davis & Hay, 2012). However, the institutional landscape in New Zealand differs from the United States in important ways, such as being much less litigious than the United States and adopting voluntary rather than mandatory rules-based governance systems (Davis & Hay, 2012; Sharma et al., 2011). With specific regard to legal and market penalties against auditors, New Zealand tends to assess them with much lower severity. Sharma et al. (2011) examine 18 years of corporate litigation cases in New Zealand and find only 14 of 417 total cases resulted in a judgement against the auditor.

Leaders of the accounting profession in New Zealand, including CEOs of the Big 4 audit firms, began to recognize the need for independent regulation and lobbied for reform just before the global financial crisis (Diplock, Jack, McLeod, Dawson, & Hunt, 2007). The catalyst for urgent reform was the series of unprecedented major finance company collapses beginning in 2006. These collapses were largely due to poor corporate governance, risky lending, and audit failures (Harris, 2009). With regard to financial reporting, New Zealand listed companies were mandated to adopt the N.Z. equivalents of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) beginning in 2007. In addition to the aforementioned factors, this decision was motivated by the Australian and European Union adoptions of IFRS (Bradbury & Van Zijl, 2005). With regard to audit regulations, New Zealand implemented an External Reporting Board (XRB) and through the FMA replaced the self-regulated audit system with an independent and more stringent, prescriptive approach similar to that of the PCAOB in the United States (Davis & Hay, 2012).

With specific regard to executive compensation, shareholders of N.Z. public companies have become increasingly vocal in their skepticism of, and opposition to, large salaries, bonuses, and share options granted to top-level management, as the compensation structure is perceived to be unrelated to actual firm performance (Morrall, 2011; Taylor, 2018). Recent publicized scandals such as that of Fuji Xerox New Zealand in 2017 exemplify this skepticism. The company launched legal action against its former executives, charging them with inappropriate accounting practices (e.g., sales at any cost) and the pursuit of incentive-based remuneration through these aggressive practices. Accordingly, there has been growing concern that executives can use their positions of power to reward themselves independently of the firm's best interest.3 Gunasekaragea and Wilkinson (2002) posit that CEO compensation practices in New Zealand have actually incentivized financial misreporting. There has also been particular concern that the pay-setting influence of the CEO may allow excess extraction of funds to the ultimate detriment of shareholders (Roberts, 2005). And most recently, initiatives such as “Closing the Gap” continue to attempt to rein in exorbitant executive salaries, stating it as good for N.Z. society and companies alike (Closing the Gap, 2018).

Shareholders' concerns over excessive and unjustified CEO compensation is also supported by the information asymmetry surrounding CEO compensation (Taylor, 2018). The nature of disclosure of CEO compensation generally, and stock options specifically, varies widely in New Zealand, making auditor assurance over this compensation potentially more valuable. It is no surprise that given the state of affairs over CEO compensation, the IFAC urged New Zealand to reform its governance over executive compensation as it relates to firm risk management (IFAC, 2010). Specifically, they note among various measures to help “prevent future financial crises” to include that “governance mechanisms need to be strengthened at banks and other companies to ensure better oversight of risk management and executive compensation” (IFAC, 2010, p. 1). Also of note is the lack of executive compensation clawback policy in New Zealand relative to the United States. Following several major financial reporting scandals in the United States, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX) mandated publicly traded firms to establish executive compensation clawback policies, which were reinforced by the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010. Such policies help firms recover incentive-based payments made to executives on the basis of financial results that turn out to be false and require restatement. Studies of clawback policy in the United States have shown improved financial reporting quality and lower audit fees (Chan, Chen, Chen, & Yu, 2012, 2014; Dehaan, Hodge, & Shevlin, 2013). Of course, the United States has much greater magnitude and complexity of incentive compensation, but the total lack of clawback policy and voluntary corporate governance practices in New Zealand may provide opportunities for management to misreport financial results that maximize incentive-based executive compensation. The auditor's recognition of this possibility (i.e., increased financial reporting risk) could manifest in higher audit fees.

2.2 Extant literature

While keeping in mind the less-established and voluntary N.Z. governance practices over executive compensation, our review of U.S. literature informs this study. As one of the first such studies, Vafeas and Waegelein (2007) examine the association between compensation incentives related to bonus plans, stock options, and long-term performance, and audit fees. They posit that the financial reporting risks inherent in incentive-based compensation may put an upward pressure on audit fees. Conversely, they also posit that incentive-based compensation may be a sound agency risk-monitoring mechanism that may be associated with less financial misreporting risks, manifesting in lower audit fees. They label this a “substitution explanation” and report some results consistent with this notion.

Later U.S. studies extend Vafeas and Waegelein (2007) and focus on analyzing the sensitivity of executive equity compensation to changes in share price (delta) and changes in return volatility (vega). Arguing the potential fraud risk associated with equity incentives, Kannan et al. (2014) examine audit fees in relation to these incentives for CEOs and CFOs. They find evidence that auditors consider the risk implicit in executive compensation arrangements and price this risk accordingly. Specifically, they find a positive association between audit fees and vega for both the CEO and CFO, but no significant results for delta. In contrast, Kim et al. (2015) find that vega is related to audit fees, but only for the CEO and not the CFO. They further document that auditors charge higher fees when firms increase the use of stock options in executive compensation.

While Fargher et al. (2014) document a positive association between audit fees and vega, they report a significant negative relationship between delta and audit fees. They explain this unexpected finding by arguing that large deltas discourage managerial risk-taking, which is contrary to the argument by Kannan et al. (2014) that large deltas pose greater financial misreporting risk. Citing the inconclusive evidence on delta in the literature, Chen et al. (2015) control for this factor and analyze how vega is related to audit fees. Consistent with the other findings, they show firms with high vega pay significantly higher audit fees, although the significance weakened in the post-SOX period. The authors find no evidence of an association between delta and audit fees.

Billings et al. (2014) describe the pervasive role of managerial incentives in accounting scandals and examine delta and vega. They find that CEO delta and vega are not related to audit fees, but CFO delta and vega are themselves related. They also report their CFO results are more pronounced in firms with weaker controls, indicating that auditors perceive greater audit risk from compensation structure in environments where internal controls are less effective. An interesting insight is provided more recently by Albrecht et al. (2018). They find that excess compensation paid to named executives is associated with greater risk of financial misreporting when these executives possess accounting competence. When they examine how auditors respond, they find that auditors are discounting the “dark-side” of executives with accounting competence when these executives receive excess compensation. Overall, this small but growing body of literature remains unclear as to how CEO compensation incentives are related to audit fees and implies more research is warranted. One aspect not considered by this prior research is a firm's internal governance, which is pivotal in monitoring management behavior, compensation, and the audit. We extend this literature by incorporating firms' internal governance as a moderating factor.

2.3 Hypotheses development

2.3.1 CEO incentive-based compensation and audit fees

There are countervailing schools of thought and literary findings on incentive-based CEO compensation and its potential effects on the audit. One line of argument is rooted in auditors' consideration of potentially heightened fraud risk stemming from incentive-based compensation. In fact, incentive-based compensation is specifically included in the auditing standard and fraud risk assessments (PCAOB, 2012, 2018). A large body of research supports the notion that such compensation can motivate management to engage in financial misreporting for various reasons (e.g., maximize compensation wealth effects, avoid adverse compensation wealth effects, protect job security, protect damaged reputation from failing to achieve expectations) (e.g., Bergstresser & Phillipon, 2006; Cheng & Warfield, 2005; Efendi, Srivastava, & Swanson, 2007; Feng, Ge, Luo, & Shevlin, 2011; Harris & Bromiley, 2007). This literature concludes that CEO compensation incentives can misalign the interests between shareholders and management, leading to agency problems.

Regulators such as the PCAOB and IFAC are also concerned about fraud risk from the potential misalignment arising from compensation incentives. Accordingly, to protect shareholders, these regulators emphasize that auditors should gain a thorough understanding of how clients structure executive compensation and assess if these arrangements impact the risk of material misstatements through fraudulent financial reporting, which also includes performing additional audit procedures (PCAOB, 2012, 2018). To the extent that performance-based compensation incentivizes managers to intentionally misreport financial statements, more audit work would be required to reduce audit risk and increase the probability of detecting fraud and material misstatements. Thus, this line of argument suggests that CEO incentive-based compensation would be positively associated with audit fees.

The counterargument is predicated on agency theory (Jensen & Meckling, 1976), which posits that CEO compensation incentives align management and shareholder interests. Such alignment reduces the incentives for managers to emphasize short-term personal gains at the expense of shareholders and promotes the communication of more accurate and value-relevant information to shareholders. Accordingly, several studies report no relation and even negative associations between CEO compensation incentives and the incidence of financial misreporting (e.g., Armstrong, Larcker, Ormazabal, & Taylor, 2013; Baber, Kang, Liang, & Zhu, 2015; Erickson, Hanlon, & Maydew, 2006). CEO equity incentives have also been shown to discourage risky investments and financial policies (Brockman, Martin, & Unlu, 2010; Chava & Purnanandam, 2010). Thus, this line of argument implies that CEO incentive compensation may be negatively associated with audit fees.

CEO incentive compensation can be considered along different dimensions, such as short-term incentives, long-term incentives, stock awards, and stock options. In the context of audit fees, Vafeas and Waegelein (2007) describe the importance of analyzing the individual components making up incentive-based compensation and call for future research doing just this. Accordingly, and similar to their study, we analyze CEO short-term incentive-based compensation, which is compensation linked to the short-term performance of the firm, including annual bonus, spot rewards, and/or retention bonus. We also analyze the existence of stock options in CEO compensation. While Vafeas and Waegelein (2007) analyze stock options as a percentage of compensation, we analyze the presence or absence of stock option compensation because our data is limited due to lack of detailed disclosure of stock options in the N.Z. setting.4

As previously described, there is a theoretical foundation for both of these incentive-based elements to have a potentially positive or negative association with audit fees. With specific regard to short-term incentive compensation, it may emphasize a focus on short-term results at the expense of long-term considerations. This form of compensation directly relates to the yearly accounting results, and as described above, can influence some executives to manipulate financial results to maximize their bonus payments and other self-interests. Such potential financial misreporting behavior stemming from CEO compensation heightens the risk of misstatements (PCAOB, 2012, 2018) that may manifest in higher audit fees.

The alternative argument suggests that incentive-based pay is associated with less CEO financial misreporting behavior, consistent with greater alignment of interests between management and shareholders, resulting in short-term compensation incentives substituting for audit effort in disciplining management (Armstrong et al., 2013; Vafeas & Waegelein, 2007). In fact, some N.Z. investors have encouraged short-term incentives for CEOs based on real financial measures, as these may create real value investors can see and benefit from (Taylor, 2018). Since we cannot be sure how short-term incentives will influence audit risk and effort in the N.Z. environment, which has substantially different compensation packages than those in the United States, and given the alternative arguments on the potential impact CEO short-term incentive compensation may have on the audit, we propose the following nondirectional hypothesis:

H1.There is no association between CEO short-term incentive compensation and audit fees.

The above theoretical discussions also apply to the presence of stock options in the CEO compensation package. As presented above, the prior literature supports both schools of thought whereby CEO stock option compensation has been shown to incentivize managers to engage in earnings management, or conversely, to align managers' interests with shareholders' such that financial misreporting is lower. Consistent with the former view, Vafeas and Waegelein (2007) find a positive association between CEO stock option compensation and audit fees, suggesting that auditors perceive and price increased risks associated with this type of compensation. The studies on equity compensation effects (i.e., delta and vega) on audit fees are mixed, and this could be due to the measures used, which from a methodological perspective supports the call by Vafeas and Waegelein (2007) to examine the actual components of CEO compensation. Our setting differs from the United States in relation to stock option compensation primarily because stock options are relatively less focal and prevalent in N.Z. CEO compensation packages. Additionally, the CEO compensation disclosures in proxy filings are far more detailed in the United States than in New Zealand, thus investors have access to much more information in the United States. Given the greater information asymmetry in New Zealand, CEOs may be incentivized by stock option compensation to take advantage of the situation and engage in opportunistic behavior, making N.Z. investors potentially more reliant on auditors to monitor the CEO's reporting behavior. Conversely, the stock options may be designed to align CEOs' incentives with shareholders'. In fact, N.Z. investors have expressed a preference for stock options in increasing the CEO's stake in the company as it creates more “skin in the game” for these executives (Taylor, 2018). Due to these countervailing effects, it is not clear how stock option compensation may be related to audit fees. Accordingly, we also propose the following nondirectional hypothesis:

H2.There is no association between CEO stock option compensation and audit fees.

Moderating Effect of Governance on the Relation between CEO Compensation and Audit Fees.

A firm's corporate governance mechanisms are known to influence both CEO compensation and audit fees. Taking first CEO compensation, directors have long been described as a central determinant of managerial pay structure (Core, Holthausen, & Larcker, 1999). The process is described as complex because compensation arrangements result from a dynamic process that involves the CEO, the directors, and the executive labor market (Shan & Walter, 2016). While some argue CEO compensation packages are a result of optimal contracting in a competitive managerial talent market (Gabaix & Landier, 2008; Himmelberg & Hubbard, 2000), an opposing view purports that CEOs exercise power over captive directors to influence their own compensation (Bebchuk et al., 2010; Bebchuk & Fried, 2006; Yermack, 1995, 2006). Both of these views are supported by research evidence that speak to differential effects of internal governance on CEO compensation (e.g., Armstrong et al., 2013; Core et al., 1999; Grinstein & Hribar, 2004; Nourayi, Kalbers, & Daroca, 2012; Sun, Cahan, & Emanuel, 2009).

More pertinent to our setting, Cahan et al. (2005) and Reddy et al. (2015) find that board characteristics such as size, duality, and overall board effectiveness are associated with CEO compensation structure in New Zealand. Additionally, N.Z. stakeholders have expressed concern over CEO influence in the pay-setting process (Roberts, 2005). These concerns seem merited given that unlike in countries such as the United States, where a CEO sitting on the compensation committee is extremely rare, this practice is far more common in New Zealand, estimated at about a third of corporations (Boyle & Roberts, 2013). Interestingly, research evidence of the CEO's presence on the compensation committee has yielded conflicting results, with some showing this influence as enabling CEOs to extract excess pay (Roberts, 2005), while a more recent study shows CEO presence on the compensation committee does not lead to excess pay, but in fact, lower CEO pay (Boyle & Roberts, 2013).

Another view in the literature suggests that greater (weaker) overall board effectiveness may be a substitute (not be a substitute) for incentive-based compensation as stronger (weaker) boards can (cannot) closely monitor CEOs to bring them in line with shareholders' interests. Stronger boards have been shown to dispense less CEO performance-based compensation (Coakley & Iliopoulou, 2006; Talmor & Wallace, 2000) while weaker boards tend to rely more heavily on performance-based compensation (Fahlenbrach, 2009). Overall, the evidence establishes a relationship between a firm's corporate governance and CEO compensation.

In relation to audit fees, there is a strong body of evidence that board and audit committee characteristics such as size, independence, expertise, and meetings have pervasive effects on auditing outcomes (see Carcello, Hermanson, and Ye (2011) and Hay (2013) for a review of this literature). These corporate governance characteristics have been shown to have potentially increasing or decreasing audit fee effects. A demand-based perspective suggests strongly (weakly) governed firms will demand higher (lower) levels of auditor assurance to protect directors' reputations and reduce exposure to litigation risk. Alternatively, a risk-based perspective suggests auditors would decrease (increase) audit fees for strongly (weakly) governed firms due to lower (greater) likelihood of internal control breakdowns and lower (higher) likelihood of financial misreporting risks (Carcello et al., 2011; Hay, 2013). In New Zealand and similar institutional settings such as the United Kingdom, Singapore, and Hong Kong, research shows that stronger board and audit committee governance are positively associated with higher audit quality, and less auditor effort (Ghafran & O'Sullivan, 2017; Griffin, Lont, & Sun, 2008; Sharma et al., 2008; Sharma et al., 2011; Sharma & Kuang, 2014; Tsui et al., 2001). Another branch of research documents that compensation incentives given to board and audit committee members can either enhance or diminish governance effectiveness in relation to audit and financial reporting outcomes (e.g., Archambeault, DeZoort, & Hermanson, 2008; Campbell, Hansen, Simon, & Smith, 2015; Cullinan, Du, & Jiang, 2010; Lin, 2018; MacGregor, 2012; Rickling & Sharma, 2017; Vafeas & Waegelein, 2007). Like the literature on governance and CEO compensation, the evidence in the governance and audit stream suggests the importance of considering a firm's governance when examining audit outcomes. Given the association of corporate governance with both CEO compensation and audit outcomes, it is important to examine the potential moderation of governance characteristics on auditor pricing of CEO compensation.

The relevance of corporate governance in the context of CEO compensation and external assurance in New Zealand is emphasized by Griffin, Lont, and Sun et al. (2009). They highlight that New Zealand’s adoption of IFRS imposed greater demands on audit effort and created far more awareness of governance practices. As part of this increased regulation, N.Z. listed firms are required to meet certain board characteristics, such as a minimum quota of independent directors, a predominantly independent audit committee, and greater auditor independence standards (Griffin, Lont, & Sun, 2009). Sporadic research supports the notion that governance mechanisms interact with client risk factors to influence audit fees. Using proprietary data, Bedard and Johnstone (2004) find that the association between the risk of financial misreporting and auditors' billing rates is significantly higher when the audit client has a weak corporate governance structure. Griffin et al. (2008) show that good governance reduces the effect of client-based audit risk on audit fees. Specifically, they find that the G-index (Gompers, Ishii, & Metrick, 2003) and board and audit committee independence mitigate (i.e., interact with) client risk such that audit fees are reduced. Mitra, Jaggi, and Al-Hayale (2019) report that strong board governance abates the association between overconfident CEOs and audit fees. Smith, Higgs, and Pinsker (2018) find that cybersecurity breaches are positively associated with audit fees but that board risk governance and more diligent audit committees reduce the audit fee premium associated with breach risks.

In related research, Albrecht et al. (2018) find some very interesting results regarding executives' accounting experience, generally considered favorably by auditing standards and market participants. In examining executives with such expertise, the authors uncover a dark side of this attribute as it appears these accounting experts engage in greater financial misreporting when their total compensation exceeds normal levels. The authors also find auditors do not recognize this increased reporting risk as the fee is lower for clients with executives receiving excess compensation and possessing accounting expertise.5 Such findings raise the question of whether auditors are appropriately pricing risks in executive compensation, which our study explores further. Albrecht et al. (2018) also highlight the need for future studies to consider interaction effects between multiple risk factors in the financial reporting and auditing process, which we respond to by examining how internal governance factors may mitigate or heighten auditor responsiveness to management compensation incentives. We also extend Albrecht et al. (2018) by examining components of compensation to isolate the impact of each incentive-based component on audit fees.

Overall, given the alternative schools of thought and the results of corporate governance research in the areas of CEO compensation, audit and financial reporting quality, and audit fees, we propose the following nondirectional hypotheses to extend our examination of short-term incentive (H1) and stock option compensation (H2) by incorporating potential moderation effects of corporate governance.

H3.There is no moderation effect of firm governance on the relationship between CEO short-term incentive compensation and audit fees.

H4.There is no moderation effect of firm governance on the relationship between CEO stock option compensation and audit fees.

3 RESEARCH DESIGN

3.1 Sample selection

Our sample is selected from the population of firms listed on the New Zealand Stock Exchange (NZX) from fiscal years 2004 to 2012.6 The financial data for all companies are obtained from the Global Vantage Database. Data for audit fees, corporate governance, executive compensation, and ownership percentage are manually extracted from the annual reports filed with the NZX. We begin with an initial sample of 2,042 firm-years. To avoid the effect of foreign audit and corporate regulations, we exclude 606 firm-years that are not headquartered in New Zealand and are dual listed on the NZX. We exclude 225 and 72 firm-years of finance and utility firms, respectively, due to their unique governance and reporting features. We exclude 290 firm-years due to data unavailability for all years. We then exclude 39 firm-years due to less than five observations per industry as we need sufficient industry samples to derive our industry-adjusted CEO compensation measures that we employ in additional analyses. Thus, our overall sample consists of a balanced panel of 810 firm-years comprising 90 unique firms for each of the nine years (2004–2012). Table 1 summarizes our sample selection procedure, and Table 2 provides the sample distribution by the NZX industry descriptors. All continuous variables are winsorized at the 1% and 99% levels.

| Firms listed on the New Zealand Stock Exchange from 2004 to 2012 | 2,042 |

| Less: Dual-listed firms & foreign firms | (606) |

| Less: Finance firms | (225) |

| Less: Utility firms | (72) |

| Less: Firms with incomplete data | (290) |

| Less: Firms with less than five observations in the industry | (39) |

| Final Sample (firm-years, 90 unique firms for each of the nine sample years) | 810 |

| Industry Description | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture and Fishing | 72 | 8.89 |

| Food | 63 | 7.78 |

| Intermediate and Durables | 63 | 7.78 |

| Property | 63 | 7.78 |

| Ports and Transport | 108 | 13.33 |

| Leisure and Tourism | 81 | 10.00 |

| Consumer | 189 | 23.33 |

| Media and Communications | 63 | 7.78 |

| Health Services | 54 | 6.67 |

| Bio-Technology | 54 | 6.67 |

| Total | 810 | 100.00 |

- Note. Industry categories are based on two-digit New Zealand Stock Exchange industry codes.

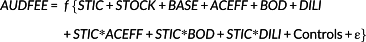

3.2 Empirical model –Audit fee regression

(1)

(1) (2)

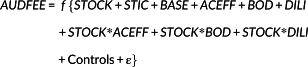

(2)To test Hypotheses 3 and 4, we introduce governance interaction terms and estimate the OLS regressions specified in Equations 3 and 4. In these equations, the variables of interest are the interaction terms whereby a significant interaction term would indicate the moderating effect of corporate governance on the association between the CEO compensation variables and audit fees. Following prior N.Z. and other governance and audit fee research (e.g., Albrecht et al., 2018; Carcello, Hermanson, Neal, & Riley, 2002; Ghafran & O'Sullivan, 2017; Griffin et al., 2008; Hay, Knechel, & Ling, 2008; Mitra et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2018; Vafeas & Waegelein, 2007), we focus on the following governance variables. These variables have been extensively studied and consistently relate to audit fees over time and across countries, and have been confirmed by Hay (2013) through a meta-analysis of audit fee research: board and audit committee independence (measured as the proportion of independent directors), audit committee accounting expertise (measured as the proportion of experts on the committee), board and audit committee meetings (measured as the number of meetings during the year), and board and audit committee size (measured as the number of directors).7

(3)

(3) (4)

(4)3.2.1 Dependent variable: Audit fees

Following the prior audit fee literature (e.g., Dunmore & Shao, 2006; Ghafran & O'Sullivan, 2017; Griffin et al., 2008, 2009; Hay, Knechel, & Li, 2006; Hay & Knechel, 2010; Kannan et al., 2014; Mitra et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2018; Venkataraman et al., 2008), our dependent variable is measured as the natural logarithm of audit fees paid to the external auditor (AUDFEE).

3.2.2 Test variables: CEO compensation and governance interactions

To test the effect of CEO incentive compensation on audit fees proposed in Hypotheses 1 and 2, we include short-term incentive compensation (STIC) and stock option (STOCK) compensation paid to the CEO. We also include the CEO's base salary compensation (BASE) as a control and estimate a baseline regression using CEO total compensation (TOTCOMP). In Equation 1, our test variable is short-term incentive compensation (STIC) and in Equation 2, our test variable is stock option compensation (STOCK). STIC includes CEO compensation linked to the short-term performance of the firm, including annual bonus, spot rewards, and/or retention bonus. Following prior research (e.g., Billings et al., 2014; Reddy et al., 2015; Vafeas & Waegelein, 2007), we employ the natural logarithm of short-term incentive compensation as our measure. Since only nine firms in our sample sporadically pay long-term incentive compensation, we exclude it from our primary analysis but consider it in our additional tests. STOCK is a dichotomous variable equal to 1 if the CEO's pay comprises stock options, and 0 otherwise. We employ an indicator variable because most firms do not disclose details on the options (i.e., value, number, vesting period).

To test the moderating effect of corporate governance on the association between CEO compensation and audit fees as espoused in Hypotheses 3 and 4, and illustrated in Equations 3 and 4, we interact STIC and STOCK with three governance variables that we derived through a factor analysis as explained above. The test variables of interest in Equation 3 are the interaction terms STIC*ACEFF, STIC*BOD, and STIC*DILI. Similarly, the test variables of interest in Equation 4 are the interaction terms STOCK*ACEFF, STOCK*BOD, and STOCK*DILI.

3.2.3 Corporate governance and other control variables

While we test the aforementioned governance interaction terms, we also include them and other governance control variables in all of our models. We discussed literature showing that executive compensation is a complex issue influenced by firm corporate governance, and similarly that corporate governance significantly influences audit fees. Consequently, we draw on the prior literature (e.g., Carcello et al., 2002; Dunmore & Shao, 2006; Ghafran & O'Sullivan, 2017; Griffin et al., 2008, 2009; Hay, 2013; Hay, Knechel, & Wong, 2006; Hay, Knechel, & Li, 2006; Hay & Knechel, 2010; Kannan et al., 2014; Mitra et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2018; Vafeas & Waegelein, 2007) and include a myriad of control variables in our empirical models that we explain next. We include the three governance factors described above (ACEFF, BOD, and DILI) and CEO duality (DUAL = 1 if the CEO also serves as the chairman of the board of directors, and 0 otherwise) and expect a positive association between these governance variables and audit fees.

Next, we include several firm characteristics. We control for firm size (SIZE = natural logarithm of total assets), number of subsidiaries (SUBS = square root of the number of subsidiaries), accounts receivable and inventory in total assets (ARINV = sum of accounts receivable and inventory scaled by total assets), debt (LEVERAGE = total long-term debt to total assets), and whether the firm engaged in a merger or acquisition (MERGER = 1 if firm reported an acquisition or merger activity in the current year, and 0 otherwise). Consistent with the prior literature, we predict positive associations between these variables and audit fees because they present various risks to the audit that can increase audit effort and/or pricing. We include firm profitability (ROA = earnings before interest and taxes scaled by total assets) and liquidity (CR = current assets to current liabilities) and based on the prior literature expect a negative coefficient on these two control variables. While we include institutional ownership (INST = cumulative percentage shares held by institutions), we do not predict an association because the prior literature finds that institutional owners can provide external monitoring and reduce risks or they may demand more audit assurance. We next include four auditor factors: audit firm size (BIGFOUR = 1 if the auditor is one of the Big 4 audit firms, and 0 otherwise), audit opinion (AUOP = 1 if the firm received a qualified or modified report, and 0 otherwise), auditor change (INITIAL = 1 if there is an auditor change in the previous year, and 0 otherwise), and nonaudit service fees (NONAUDFEE = natural logarithm of total nonaudit fees paid by the firm to the auditor). Based on the prior literature, we expect all except INITIAL to have positive associations with audit fees. We also include IFRS control variables that indicate the timing of adoption (PREIFRS, IFRS, and POSTIFRS) as Griffin et al. (2009) find that audit fees in New Zealand are higher when firms adopt IFRS and expect positive coefficients. Finally, we control for industry (IND_FE) and year (YEAR_FE) fixed-effects to control for industry and time effects.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Descriptive statistics

We present descriptive statistics for our audit fee variables in Table 3. The mean and median audit fees are $258,340 and $82,030, respectively. The mean and median total CEO compensation is $692,700 and $331,140, respectively. Disaggregating this into base compensation and short-term incentive compensation, the means (medians) are $554,470 ($331,120) and $138,220 ($0), respectively. The mean (median) stock options awarded to CEOs is 0.41 (0.25), suggesting that on average, 41% of firms are offering and disclosing this form of equity incentive compensation. The mean and median total assets of our sample firms are $489,000,000 and $106,510,000, respectively. Summary statistics on all other variables are provided in Table 3.

| Variable | M | Mdn | SD | Q1 | Q3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Audit Fees ($000) | 258.34 | 82.03 | 165.94 | 52.00 | 404.15 |

| AUDFEE | 11.09 | 11.31 | 3.21 | 10.58 | 12.91 |

| BASE ($000) | 554.47 | 331.12 | 232.57 | 189.21 | 875.66 |

| BASE | 13.12 | 12.71 | 3.14 | 12.15 | 13.68 |

| STIC ($000) | 138.22 | 0.00 | 151.55 | 0.00 | 251.26 |

| STIC | 11.83 | 0.00 | 2.16 | 0.00 | 12.43 |

| STOCK | 0.41 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| TOTCOMP ($000) | 692.70 | 331.14 | 384.12 | 189.23 | 926.92 |

| TOTCOMP | 13.44 | 12.71 | 2.85 | 12.15 | 13.74 |

| ACEFF | 0.00 | −0.01 | 1.00 | −0.73 | 0.76 |

| BOD | 0.00 | −0.05 | 1.00 | −0.63 | 0.65 |

| DILI | 0.00 | −0.03 | 1.00 | −0.71 | 0.67 |

| TA ($m) | 489.00 | 106.51 | 1100.12 | 24.12 | 9964.57 |

| SIZE | 21.50 | 19.28 | 4.08 | 16.98 | 23.02 |

| SUBS | 1.79 | 1.00 | 1.87 | 0.00 | 3.32 |

| ARINV | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.65 |

| LEVERAGE | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.37 |

| MERGER | 0.51 | 1.00 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| ROA | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 0.08 |

| DUAL | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| CR | 4.57 | 1.48 | 7.62 | 0.92 | 2.33 |

| INST | 0.35 | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.48 |

| BIGFOUR | 0.84 | 1.00 | 0.38 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| AUOP | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| INITIAL | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| NONAUDFEE | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.14 |

| PREIFRS | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| IFRS | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| POSTIFRS | 0.58 | 1.00 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

- Note. All variables are defined in the Appendix.

4.2 Correlation analysis

Table 4 presents Pearson and Spearman correlations for our independent variables. We find a significant positive correlation (0.85) between total compensation (TOTCOMP) and base compensation (BASE), as the former contains the latter, and they are thus not included in the same regressions. Our variance inflation factors (VIFs) are in the range of 2 to 3, well below the multicollinearity threat thresholds of 10 (Gujarati, 2003). Since the data involve the same companies over a 9-year period, we also run a time-series test for auto-serial correlation and find the Durbin-Watson coefficients are around 1.914 across all our regressions. Moreover, we employ firm-level clustered robust standard errors in all our regressions to address heteroscedasticity (Petersen, 2009) and include year fixed-effects.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUDFEE (1) | 1.00 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.36 | 0.21 | 0.67 | 0.55 | 0.01 | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.07 | −0.23 | −0.01 |

| TOTCOMP (2) | 0.53 | 1.00 | 0.73 | 0.32 | 0.84 | −0.18 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.09 | −0.03 |

| STIC (3) | 0.30 | 0.73 | 1.00 | 0.32 | 0.11 | −0.14 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.28 | 0.25 | −0.02 | 0.14 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.10 | −0.03 |

| STOCK (4) | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 1.00 | 0.13 | −0.09 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.21 | −0.03 | 0.15 | 0.03 | −0.02 | −0.09 | −0.04 |

| BASE (5) | 0.55 | 0.85 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 1.00 | −0.13 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.07 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| ACEFF (6) | 0.05 | −0.11 | −0.14 | −0.09 | −0.08 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.09 | 0.03 | −0.08 | −0.25 | 0.00 | −0.19 | 0.04 |

| BOD (7) | 0.34 | 0.23 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.29 | 0.04 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.31 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.04 | −0.11 | −0.04 |

| DILI (8) | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.17 | −0.04 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.19 | 0.23 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| SIZE (9) | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.52 | −0.03 | 0.41 | 0.21 | 1.00 | 0.49 | −0.15 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.09 | −0.18 | −0.04 |

| SUBS (10) | 0.52 | 0.41 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.42 | −0.10 | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.49 | 1.00 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | −0.13 | 0.02 |

| ARINV (11) | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.10 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.09 | −0.19 | 0.12 | 1.00 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 |

| LEVERAGE (12) | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.17 | −0.20 | 0.12 | −0.02 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 0.12 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.01 |

| MERGER (13) | −0.06 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.25 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | −0.02 |

| ROA (14) | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.20 | −0.08 | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 1.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 |

| DUAL (15) | −0.23 | −0.17 | −0.11 | −0.09 | −0.16 | −0.19 | −0.10 | 0.01 | −0.17 | −0.13 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 1.00 | −0.01 |

| CR (16) | −0.07 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.04 | −0.08 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.10 | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.11 | −0.03 | 0.09 | 1.00 |

| INST (17) | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.14 | −0.04 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.14 | −0.09 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.15 | −0.02 | −0.03 |

| BIGFOUR (18) | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.28 | −0.11 | 0.29 | 0.07 | 0.34 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.15 | −0.11 | 0.04 |

| AUOP (19) | −0.07 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| INITIAL (20) | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.06 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.09 | 0.02 | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.04 | −0.03 |

| NONAUDFEE (21) | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.18 | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.13 | −0.04 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.11 | −0.02 | −0.07 |

| PREIFRS (22) | −0.08 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.13 | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.04 | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| IFRS (23) | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.13 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.07 | −0.02 | −0.04 |

| POSTIFRS (24) | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.38 | −0.03 | −0.04 | 0.10 | 0.12 | −0.16 | −0.28 | −0.47 | −0.20 | −0.29 | −0.05 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUDFEE (1) | 0.12 | 0.31 | −0.06 | −0.02 | 0.10 | −0.08 | −0.03 | 0.22 |

| TOT (2) | 0.15 | 0.20 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.13 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.07 |

| STIC (3) | 0.15 | 0.14 | −0.03 | −0.06 | 0.14 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.11 |

| STOCK (4) | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| BASE (5) | 0.06 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.04 |

| ACEFF (6) | −0.02 | −0.09 | −0.04 | −0.08 | −0.09 | −0.12 | −0.12 | 0.37 |

| BOD (7) | 0.14 | 0.28 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.06 | −0.02 |

| DILI (8) | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.04 |

| SIZE (9) | 0.21 | 0.34 | −0.07 | −0.03 | 0.14 | −0.04 | 0.00 | 0.11 |

| SUBS (10) | 0.13 | 0.11 | −0.06 | 0.00 | 0.07 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.12 |

| ARINV (11) | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| LEVERAGE (12) | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.04 | −0.11 |

| MERGER (13) | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.17 | −0.47 |

| ROA (14) | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.03 |

| DUAL (15) | −0.02 | −0.11 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.05 | −0.02 | −0.29 |

| CR (16) | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.06 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| INST (17) | 1.00 | 0.21 | −0.06 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.07 | −0.11 |

| BIGFOUR (18) | 0.21 | 1.00 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 |

| AUOP (19) | −0.06 | −0.03 | 1.00 | −0.01 | −0.06 | 0.05 | −0.02 | −0.03 |

| INITIAL (20) | 0.09 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 1.00 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.07 |

| NONAUDFEE (21) | 0.11 | 0.10 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 0.07 | 0.08 | −0.23 |

| PREIFRS (22) | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 1.00 | −0.11 | −0.40 |

| IFRS (23) | 0.07 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.08 | −0.11 | 1.00 | −0.40 |

| POSTIFRS (24) | −0.11 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.07 | −0.16 | −0.40 | −0.40 | 1.00 |

- Note. Bold coefficients are significant at p < 0.05. All variables are defined in the Appendix.

4.3 Regression results

In Table 5, we present the results of our analyses. We first report a baseline model that regresses audit fees on total CEO compensation, followed by the audit fee regressions testing Hypotheses 1, 2, 3, and 4. All our audit fee regressions have explanatory power comparable to prior N.Z. (Griffin et al., 2008, 2009; Hay, Knechel, & Li, 2006) and other studies. The baseline results in Column 1 of Table 5 show the coefficient on total CEO compensation (TOTCOMP) is positive and significant (p < 0.01). The results in Column 2 of Table 5 test Hypotheses 1 and 2 that examine the association between audit fees and the incentive components of total compensation, short-term incentive (STIC), and stock option (STOCK) compensation paid to the CEO, with base salary (BASE) serving as a control. The results show the coefficient on short-term incentive compensation (STIC) is positive and significant (p < 0.01). This suggests that CEO compensation derived from short-term performance incentives such as annual bonus, spot rewards, and/or retention bonus presents risks that are considered and priced by the auditor. This finding rejects the null association proposed in Hypothesis 1. Similarly, the results in Column 2 of Table 5 show that the coefficient on stock option compensation (STOCK) is positive and significant (p < 0.05). This finding suggests rejection of the null association in Hypothesis 2 and implies that audit fees are higher when CEOs receive stock options. Taken together, the findings on short-term incentive and stock option compensation suggest that auditors consider and price performance-based compensation paid to the CEO. However, our CEO compensation control variable results suggest that auditors do not price base (BASE) compensation paid to the CEO, as the coefficient on this control variable is not significant, which is consistent with the fact that this component of compensation is not contingent on firm performance and is fairly static, thus it may not pose financial reporting risks for the audit.

| (1) Baseline Model | (2) Short-Term Incentives | (3) Short-Term Incentives & Governance Interactions | (4) Stock Options | (5) Stock Options and Governance Interactions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable: Variable (predicted sign) | AUDFEE | AUDFEE | AUDFEE | AUDFEE | AUDFEE | |||||

| Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | |

| TOTCOMP(?) | 0.026 | 5.961*** | ||||||||

| STIC (?) | 0.029 | 5.366*** | 0.027 | 4.894*** | 0.030 | 5.637*** | 0.029 | 5.152*** | ||

| STOCK (?) | 0.102 | 2.134** | 0.134 | 2.802*** | 0.083 | 1.970** | 0.117 | 2.411** | ||

| BASE (?) | 0.013 | 1.552 | 0.011 | 1.318 | 0.012 | 1.429 | 0.010 | 1.233 | ||

| ACEFF (+) | 0.049 | 1.900** | 0.054 | 2.106** | 0.109 | 3.730*** | 0.087 | 2.720*** | 0.130 | 3.862*** |

| BOD (+) | −0.020 | −0.754 | −0.023 | −0.892 | −0.031 | −1.123 | −0.058 | −1.758** | −0.061 | −1.831** |

| DILI (+) | 0.072 | 2.945*** | 0.073 | 2.979*** | 0.134 | 4.756*** | 0.099 | 3.208*** | 0.135 | 4.254*** |

| STIC*ACEFF (?) | −0.010 | −2.009** | −0.009 | −1.747* | ||||||

| STIC*BOD (?) | 0.009 | 1.618 | 0.006 | 1.161 | ||||||

| STIC*DILI (?) | −0.016 | −3.537*** | −0.016 | −3.358*** | ||||||

| STOCK*ACEFF (?) | −0.071 | −1.585 | −0.058 | −1.291 | ||||||

| STOCK*BOD (?) | 0.092 | 2.049** | 0.084 | 1.856* | ||||||

| STOCK*DILI (?) | −0.071 | −1.596 | −0.009 | −0.184 | ||||||

| SIZE (+) | 0.336 | 21.282*** | 0.331 | 20.917*** | 0.314 | 19.656*** | 0.331 | 20.950*** | 0.314 | 19.451*** |

| SUBS (+) | 0.228 | 16.156*** | 0.227 | 16.112*** | 0.228 | 16.358*** | 0.225 | 16.072*** | 0.226 | 16.263*** |

| ARINV (+) | 0.006 | 6.163*** | 0.007 | 6.261*** | 0.006 | 6.187*** | 0.007 | 6.286*** | 0.006 | 6.137*** |

| LEVERAGE (+) | 0.107 | 2.214** | 0.098 | 2.022** | 0.107 | 2.247** | 0.103 | 2.146** | 0.110 | 2.315** |

| MERGER (+) | 0.088 | 1.512* | 0.095 | 1.644* | 0.109 | 1.906** | 0.091 | 1.580* | 0.105 | 1.835** |

| ROA (−) | −0.013 | −0.590 | −0.009 | −0.436 | −0.003 | −0.134 | −0.014 | −0.662 | −0.005 | −0.216 |

| DUAL (+) | 0.060 | 0.637 | 0.070 | 0.751 | 0.050 | 0.536 | 0.052 | 0.553 | 0.043 | 0.462 |

| CR (−) | 0.000 | −0.630 | 0.000 | −0.588 | 0.000 | −0.755 | 0.000 | −0.645 | 0.000 | −0.796 |

| INST (?) | −0.061 | −1.264 | −0.075 | −1.555 | −0.068 | −1.431 | −0.076 | −1.584 | −0.071 | −1.489 |

| BIGFOUR (+) | 0.267 | 3.930*** | 0.276 | 4.053*** | 0.293 | 4.347*** | 0.289 | 4.233*** | 0.306 | 4.515*** |

| AUOP (+) | 0.166 | 0.478 | 0.166 | 0.478 | 0.128 | 0.375 | 0.212 | 0.612 | 0.150 | 0.435 |

| INITIAL (−) | −0.098 | −0.532 | −0.075 | −0.409 | −0.041 | −0.226 | −0.055 | −0.300 | −0.032 | −0.178 |

| NONAUDFEE (+) | 0.005 | 1.164 | 0.005 | 1.030 | 0.005 | 1.054 | 0.004 | 0.964 | 0.005 | 1.027 |

| PREIFRS (+) | −0.019 | −0.233 | −0.015 | −0.178 | −0.017 | −0.202 | −0.018 | −0.220 | −0.015 | −0.182 |

| IFRS (+) | 0.004 | 0.046 | 0.006 | 0.067 | 0.001 | 0.017 | 0.003 | 0.039 | 0.001 | 0.014 |

| POSTIFRS (+) | 0.026 | 0.338 | 0.028 | 0.365 | −0.015 | −0.192 | 0.015 | 0.188 | −0.021 | −0.268 |

| INTERCEPT (?) | 3.861 | 9.743*** | 4.116 | 10.070*** | 4.451 | 10.866*** | 4.130 | 10.135*** | 4.810 | 11.743*** |

| IND_FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | ||||||

| Regressions of Audit Fees on Components of Compensation and Governance Interactions | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Baseline Model | (2) Short-Term Incentives | (3) Short-Term Incentives & Governance Interactions | (4) Stock Options | (5) Stock Options and Governance Interactions | ||||||

| Dependent Variable: Variable (predicted sign) | AUDFEE | AUDFEE | AUDFEE | AUDFEE | AUDFEE | |||||

| Coeff | t-stat | Coeff | t-stat | Coeff | t-stat | Coeff | t-stat | Coeff | t-stat | |

| YEAR FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |||||

| Observations | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 810 | |||||

| F-Statistic | 77.284*** | 74.211*** | 71.603*** | 69.675*** | 67.219*** | |||||

| Adj. R2 | 0.791 | 0.792 | 0.798 | 0.794 | 0.799 | |||||

- *, **, *** denote significance at the 0.10, 0.05, and 0.01 levels, respectively.

- Note. Directional tests are one-tailed, otherwise two-tailed. We estimate the ordinary lease squares (OLS) regression models with firm-level clustered robust (heteroscedasticity-consistent) standard errors. All variables are defined in the Appendix.

The results presented in Columns 3 and 4 test Hypotheses 3 and 4 that proposed there is no moderation effect of governance on the association between CEO compensation and audit fees. In Column 3, the coefficient on STIC, which captures the association between CEO short-term incentive compensation and audit fees in the absence of governance, is positive and significant (p < 0.01). With regard to the governance interactions, coefficients on two of the three are significant. Specifically, the coefficient on STIC*ACEFF is negative and significant (p < 0.05) and the coefficient on STIC*DILI is also negative and significant (p < 0.01). These results suggest that the association between short-term incentive compensation and audit fees is moderated by the governance factors of audit committee effectiveness (ACEFF) and diligence (DILI), but not by board resources (BOD). This may be due to the audit committee's direct oversight of the financial reporting process, which the auditor recognizes and considers when assessing financial reporting and fraud risks arising from short-term incentives paid to the CEO (PCAOB, 2012, 2018). Since the short-term incentives in our setting comprises mainly cash bonuses, a relatively more straightforward component of compensation, an appropriately qualified and diligent audit committee is more likely to fairly and easily monitor this type of compensation without the greater board needing to get involved.

Moving on to the results in Column 4, the coefficient on STOCK, which captures the association between CEO stock option compensation and audit fees in the absence of governance, is positive and significant (p < 0.05). The interactions between STOCK and both ACEFF and DILI are insignificant, but STOCK*BOD is positive and significant (p < 0.05). Taken together, these results suggest that strong governance at the board level heightens the demand for additional audit effort when the CEO is paid with stock options.8 Stronger boards may demand greater auditor assurance over stock options because of their inherent risk and complexity. Also, the lack of prescribed N.Z. CEO stock option disclosure requirements may intensify the board's concern over the clarity of stock options. Additionally, the larger board (not audit committee) is responsible for setting executive compensation in New Zealand, so given the relatively more opaque incentive-based component of stock options, the audit committee may not be in as strong a position to assess it relative to financial reporting and thus may rely more on the board. As our board factor captures independence and size, more independent and larger boards face greater exposure to market scrutiny, which would likely motivate such boards to protect their reputation by seeking greater assurance from the auditor given increasing N.Z. investor concern over stock option compensation (Taylor, 2018).

With respect to the control variables, our results are similar to prior research. For example, the governance control variables of audit committee effectiveness (ACEFF) and board diligence (DILI) are positive and significant. This is similar to prior research that generally finds individual governance variables such as accounting expertise on the audit committee, audit committee independence, and board and audit committee meetings to be positively related to audit fees, while board and audit committee size tend to have mixed associations with audit fees (see Hay, 2013, for a meta-analysis of the audit fee literature). Similar to prior research (see Hay, 2013), we find several firm characteristics (SIZE, SUBS, ARINV, LEV, MERGER, and BIGFOUR) are positive and significantly related to audit fees.

Taken together, the results suggest that auditors pay attention to CEO performance-based compensation and price this into audit fees. Given that CEO short-term incentive and stock option compensation are linked to firm performance, and such CEO compensation is known to incentivize earnings management, our results are consistent with the view that auditors are considering potential financial reporting risks stemming from short-term incentive compensation and stock options. Moreover, our results suggest that stronger corporate governance mitigates auditors' upward pricing of short-term incentive CEO compensation. This governance mitigating effect is consistent with auditors adopting a risk-based perspective. Conversely, auditors' consideration of stock option compensation is positively influenced by the strength of firm governance, in particular, board resources, which may be due to the risk in options that is consistent with the view that stock option compensation is inherently more complex, thus requiring additional audit assurance. Stronger boards may be even more demanding of such assurance given the complexity and lack of consistent stock option disclosure in New Zealand.

As we reflect on the results, we conclude that there is sufficient collective evidence to reject the null hypotheses in H1 (short-term incentive compensation is not associated with audit fees), H2 (stock option compensation is not associated with audit fees), and H3 and H4 (no moderation effect of governance on CEO compensation and audit fees). Our evidence is consistent with some of the prior literature that supports auditor pricing of executive equity-based compensation (e.g., Chen et al., 2015; Fargher et al., 2014; Kannan et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2015; Vafeas & Waegelein, 2007), with our study extending this body of knowledge by documenting that specific components of CEO compensation are related to audit fees, and that a firm's corporate governance moderates these associations. As the degree of public disclosure of CEO stock option compensation by N.Z. firms varies cross-sectionally, our study suggests that auditors' consideration of this compensation through access to private information provides some level of assurance to investors. This is likely due to auditors evaluating the financial reporting implications of the complexities and risks inherent in stock option compensation.

4.4 Additional analyses

For greater confidence in our results, we conduct several additional analyses. First, given that auditors may learn more about CEO compensation risks over the course of the current year audit that could impact the following year's audit pricing, we re-perform all of our regressions using current year compensation measures and next year audit fees. Phrased in a different way, auditors can price the current year's audit based on risks discovered during the prior year audit. Thus, we perform lead–lag analyses by estimating regressions of (1) current year fees on prior year compensation and (2) next year fees on current year compensation. While both sets of results are consistent with those reported in Table 5, for brevity, we report our results for prior year compensation effects on audit fees in Panel A of Table 6. We also consider client engagement tenure because a new auditor may not have the opportunity to learn about the client from prior audits. Thus, we restrict our sample to continuing audit engagements (INITIAL = 0) and reestimate our main and the lead–lag regressions and find that all of our results (untabulated) remain the same.

| Panel A: Prior year analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable: Variable (predicted sign) | AUDFEE | AUDFEE | AUDFEE | |||

| Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | |

| STIC (?) | 0.024 | 3.849*** | 0.027 | 3.388*** | 0.026 | 3.867*** |

| STOCK (?) | 0.131 | 2.548*** | 0.155 | 2.992*** | 0.136 | 2.658*** |

| ACEFF (+) | 0.061 | 2.222** | 0.053 | 1.703** | 0.054 | 1.536* |

| BODAC (+) | −0.014 | −0.480 | −0.034 | −1.161 | −0.076 | −2.095** |

| DILI (+) | 0.075 | 2.919*** | 0.090 | 3.045*** | 0.064 | 1.916** |

| STIC*ACEFF (?) | −0.213 | −2.125** | ||||

| STIC*BOD (?) | 0.005 | 0.749 | ||||

| STIC*DILI (?) | −0.011 | −2.045** | ||||

| STOCK*ACEFF (?) | −0.027 | −0.549 | ||||

| STOCK*BOD (?) | 0.097 | 1.995** | ||||

| STOCK*DILI (?) | −0.007 | −0.152 | ||||

| CONTROL VARIABLES | YES | YES | YES | |||

| Observations | 762 | 762 | 762 | |||

| F-Statistic | 69.219*** | 71.802*** | 59.327*** | |||

| Adj. R2 | 0.773 | 0.793 | 0.782 | |||

| Panel B: Industry-mean adjusted regressions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable: Variable (predicted sign) | AUDFEE | AUDFEE | |||

| Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | ||

| STIC (?) | 0.016 | 2.002** | 0.206 | 2.060** | |

| STOCK (?) | 0.065 | 2.973** | 0.161 | 3.332*** | |

| ACEFF (+) | 0.023 | 1.578* | 0.063 | 2.249** | |

| BODAC (+) | 0.010 | 0.348 | −0.041 | −1.526 | |

| DILI (+) | 0.070 | 2.549*** | 0.092 | 3.420*** | |

| STIC*ACEFF (?) | −0.043 | −2.412** | |||

| STIC*BOD (?) | 0.098 | 1.130 | |||

| STIC*DILI (?) | −0.145 | −2.052** | |||

| STOCK*ACEFF (?) | |||||

| STOCK*BOD (?) | |||||

| STOCK*DILI (?) | |||||

| CONTROL VARIABLES | YES | YES | |||

| Observations | 810 | 810 | |||

| F-Statistic | 74.147*** | 78.241*** | |||

| Adj. R2 | 0.792 | 0.794 | |||

| Panel C: Regressions by high and low litigation risk industries | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Litigation | Low Litigation | |||||||||||

| (Dependent Variable: Variable (predicted sign) | AUDFEE | AUDFEE | AUDFEE | AUDFEE | AUDFEE | AUDFEE | ||||||

| Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | Coeff. | t-stat | |

| STIC (?) | 0.014 | 2.377** | 0.016 | 2.659*** | 0.015 | 2.526** | 0.069 | 6.808*** | 0.071 | 6.908*** | 0.070 | 7.041*** |

| STOCK (?) | 0.192 | 3.345*** | 0.201 | 3.551*** | 0.186 | 3.254*** | −0.060 | −0.680 | −0.023 | −0.263 | −0.062 | −0.688 |

| ACEFF (+) | 0.062 | 1.932** | 0.077 | 2.314** | 0.070 | 2.116** | 0.132 | 2.816*** | 0.170 | 3.644*** | 0.135 | 2.855*** |

| BOD (+) | 0.036 | 1.123 | 0.038 | 1.217 | 0.005 | 0.160 | −0.132 | −2.709*** | −0.094 | −1.847* | −0.145 | −2.886*** |

| DILI (+) | 0.053 | 1.806** | 0.089 | 2.911*** | 0.044 | 1.461* | 0.102 | 2.186** | 0.120 | 2.525*** | 0.124 | 2.558*** |

| STIC*ACEFF (?) | −0.079 | −2.673*** | −0.026 | −0.655 | ||||||||

| STIC*BOD (?) | 0.010 | 1.631 | −0.003 | −0.480 | ||||||||

| STIC*DILI (?) | −0.045 | −1.744* | −0.191 | −5.026*** | ||||||||

| STOCK*ACEFF (?) | −0.121 | −1.408 | 0.029 | 0.420 | ||||||||

| STOCK*BOD (?) | 0.026 | 2.115** | 0.058 | 0.796 | ||||||||

| STOCK*DILI (?) | 0.066 | 1.329 | −0.148 | −3.741*** | ||||||||

| CONTROL VARIABLES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | ||||||

| OBSERVATIONS | 504 | 504 | 504 | 306 | 306 | 306 | ||||||

| F-STATISTIC | 56.998*** | 53.105*** | 51.995*** | 33.282*** | 32.893*** | 31.353*** | ||||||

| Adj.R2 | 0.796 | 0.802 | 0.798 | 0.772 | 0.790 | 0.782 | ||||||

- *, **, *** denote significance at the 0.10, 0.05, and 0.01 levels, respectively.

- Note. Directional tests are one-tailed, otherwise two-tailed. We estimate the ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions with firm-level clustered robust (heteroscedasticity-consistent) standard errors. All variables are defined in the Appendix. The regressions in (1) Panel A employ industry mean-adjusted measures for the compensation variables, (2) Panel B employ prior year (t-1) compensation variables, and (3) Panel C are estimated on subsamples of high- and low-industry litigation risk as described in the text.

Second, we consider if our results differ between Big 4 and non–Big 4 audit firms. Generally, the expectation is that Big 4 audit firms will provide greater audit quality and thus may pay more attention to risks in CEO compensation compared to non–Big 4 auditors because larger audit firms have deeper pockets, and thus face a greater risk of potential litigation (Hay, Knechel, & Wong, 2006). However, we note our study is situated in the low auditor–penalty risk context of New Zealand (Sharma et al., 2011), which conversely suggests that both Big 4 and non-Big 4 auditors face a low risk of litigation and reputational consequences. When we reestimate our results for subsamples of the Big 4 and non–Big 4 auditors, our results are the same for both types of audit firms.

Third, we exclude firms that give spot or retention bonuses (42 firm-years) from our short-term incentive compensation (STIC) calculation and reestimate the regressions where STIC contains only cash bonuses. All our results are again consistent with our primary results (p < 0.01). Fourth, we previously noted excluding long-term incentive compensation from our analyses because it is rarely used in New Zealand (only nine companies [6.5%] in our sample sporadically report this type of CEO compensation). When we include long-term incentive compensation paid to CEOs in our regressions, we find it to be insignificantly related to audit fees. Results on our other CEO compensation variables are not sensitive to the inclusion of this variable. The insignificant result of long-term incentive compensation may be due to its low incidence (low power), or it may suggest auditors believe long-term incentives to the CEO pose less financial misreporting risk.