Uncertain tax benefits, international tax risk, and audit specialization: Evidence from US multinational firms

Abstract

The purpose of this study is twofold. First, it examines the association between income-shifting arrangements consisting of transfer pricing aggressiveness, tax haven use and foreign tax rate differentials, and Financial Interpretation No. 48 (FIN48, now ASC740–10-25) unrecognized tax benefits (UTBs). Second, it analyzes the impact of audit specialization on the association between income-shifting arrangements and UTBs. Using a dataset of 286 US multinational firms over the 2007–2016 period (2,097 firm-years), our regression results show that income-shifting arrangements represented by transfer pricing aggressiveness, tax haven use and foreign tax rate differentials are significantly positively associated with UTBs. We also observe that audit specialization magnifies the positive association between transfer pricing aggressiveness and UTBs, and foreign tax rate differentials and UTBs. Finally, in additional analysis we provide some evidence that the positive association between income-shifting arrangements and UTBs is magnified in the post-2010 uncertain tax position reporting requirement period. Overall, our study extends prior research on the topic of audit characteristics (i.e., audit specialization) and tax aggressiveness.

1 INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this study is twofold. First, it examines the association between income-shifting arrangements relating to transfer pricing aggressiveness, tax haven use and foreign tax rate differentials, and Financial Interpretation No. 48 (FIN48, now ASC740–10-25) unrecognized tax benefits (UTBs).1 Second, it analyzes the impact of audit specialization on the association between income-shifting arrangements and UTBs.

Income shifting can be described as a plan or structure that leads to more income being earned in low-tax jurisdictions than would otherwise be expected based on a firm's worldwide asset allocation (Klassen & Laplante, 2012a). Income-shifting arrangements impose a significant amount of uncertainty as reflected in the calculation of a firm's UTBs (Lisowsky, Robinson, & Schmidt, 2013; Mills, Robinson, & Sansing, 2010; Rego & Wilson, 2012). In particular, management is faced with much uncertainty in determining whether tax benefits recorded in a firm's tax returns are likely to be sustained following audit by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and also the specific amount of UTBs reported in a firm's financial statements (Lisowsky et al., 2013; Mills et al., 2010; Rego & Wilson, 2012). In fact, the computation of UTB estimates requires a great deal of judgment by management due to the significant uncertainties, complexities, and subjectivity dealing with the application of tax legislation and case law, and the nature, timing, and settlement of anticipated audits by the IRS (Blouin & Robinson, 2012; Ciconte, Donohoe, Lisowsky, & Mayberry, 2016; Tax Executives Institute [TEI], 2011). Given that audit client risk and complexity are major drivers of audit fees (Donohoe & Knechel, 2014), it is therefore not unreasonable to expect that audit specialization plays an important role in the association between income-shifting arrangements and UTB estimates.

We are motivated in this study to examine the association between UTB estimates and major areas of income-shifting arrangements for two important reasons. First, prior research shows that US multinational firms encounter significant uncertainty concerning the recording of tax benefits (e.g., transfer pricing benefits) and their ultimate tax positions (e.g., Blouin, Devereux, & Shackelford, 2012; Hutchens & Rego, 2013; Lisowsky et al., 2013; Neuman, Omer, & Schmidt, 2013; Rego & Wilson, 2012). Hanlon and Heitzman (2010) argue that larger UTB estimates denote a greater amount of uncertainty of a firm's tax position and its level of corporate tax aggressiveness.22 Other researchers also claim that the magnitude of UTBs is a function of the uncertainty of a firm's underlying tax position (e.g., Cazier, Rego, Tian, & Wilson, 2015). Robinson, Stomberg, & Towery (2016) find that over a 3-year period, some 24 cents in every dollar of UTB reverses as a result of IRS audit settlements. In fact, IRS settlements are highly variable and can range from a zero adjustment to a substantial reversal of a recorded UTB amount in a particular year. While the tax benefit is generally more likely than not to result from a series of transactions or arrangements, the total amount of the benefit is uncertain because of the subjectivity or complexity involved in those transactions. This uncertainty is manifested by the quantum of UTBs recorded, any magnitude of difference between actual and predicted UTBs, and audit adjustments to the UTB amount. Overall, firms have come under increased scrutiny by the IRS in terms of an array of income-shifting activities that can lead to considerable uncertainty in determination of their tax positions (, 2012; , 2013a; , 2013b; IRS, 2010).

Second, external audit firms have added responsibilities following the implementation of FIN48, such as assisting a firm with the recognition and measurement of recognized tax benefits and the computation and disclosure of UTBs (Donohoe & Knechel, 2014). Hence, many new auditing challenges arise due to the implementation of FIN48, and a firm's aggressive tax positions are also likely to generate further audit risk and effort on the part of external audit firms. In addition to the uncertainties in applying tax laws to various transactions and arrangements, a firm also faces uncertainty about the outcome of audits by the IRS which may reduce some or all of its UTB estimates (FASB, 2006). Thus, we also conjecture that audit specialization is likely to significantly impact the association between income shifting arrangements and UTBs.

Employing a dataset of 286 US multinational firms over the 2007–2016 period (2,097 firm-years), our regression results show that income-shifting arrangements denoted by transfer pricing aggressiveness, tax haven use, and foreign tax rate differentials are significantly positively associated with UTBs. We also observe that audit specialization magnifies the positive association between transfer pricing aggressiveness and UTBs, and foreign tax rate differentials and UTBs. Finally, in additional analysis we provide some evidence that the positive association between income-shifting arrangements and UTBs is magnified in the post-2010 uncertain tax position (UTP) reporting requirement period.

This study makes the following important contributions. First, it shows that audit specialization magnifies the positive association between transfer pricing aggressiveness and UTBs, and foreign tax rate differentials and UTBs. To the best of our knowledge, no prior study has analyzed the linkages between audit characteristics in terms of audit specialization, income-shifting arrangements and UTB estimates. Second, in additional analysis, we furnish some new evidence showing that the positive association between income-shifting arrangements and UTBs is magnified in the post-2010 UTP reporting requirement period. Third, this study is also timely because there are several audit implications stemming from large or abnormal UTB estimates. For instance, the link between the financial and tax reporting of UTBs post implementation of the UTP reporting requirement from 2010 has placed greater pressure on auditors with regard to identifying and evaluating possible tax uncertainties (Robinson & Schmidt, 2013). Finally, the results of this study should be of interest to auditors, policymakers, regulators and tax authorities (e.g. the IRS).

The rest of this paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 provides the background to FIN48 and the calculation of a firm's UTB estimates. Section 3 considers theory about tax aggressiveness, external audit, and UTBs, while Section 4 develops our hypotheses. Section 5 describes the research design, and Section 6 reports the empirical results. Finally, Section 7 concludes.

2 BACKGROUND TO FIN48 AND THE CALCULATION OF UNRECOGNIZED TAX BENEFITS

In July 2006, the FASB (2006) issued FIN48, which became effective for fiscal years after December 15, 2006. According to FIN48, a firm recognizes a tax benefit in its financial statements for a UTB only if management's assessment is that its position is more likely than not (i.e., a greater than 50% likelihood) to be upheld on audit based only on the technical merits (i.e., legislation, legislative intent, and precedent cases) of the tax position. UTBs denote the difference between a tax position taken or expected to be taken in a firm's tax return and the benefit recognized and measured based on FIN48 requirements. A liability is created as it represents a potential future obligation to the IRS if a firm is unable to recognize the tax benefits on a tax filing pursuant to FIN48 requirements (FASB, 2006). The presumption is that the IRS possesses full knowledge of a firm's tax reporting position, together with all of the pertinent facts and details of arrangements that affect its tax position. Resolution of a firm's related tax positions through negotiation with the IRS or by litigation can take many years to finalize.

The computation of a firm's UTB estimates requires a great deal of judgment by management because of the significant uncertainties associated with estimating its tax liabilities (e.g., provision for taxes based on the global variability in taxes to be paid) or tax assets (e.g., estimates of deferred tax assets based on the criteria that tax losses will probably be recouped at a future point in time). These risks arise due to the high likelihood of a mismatch between the reported tax expense (and liability) of a firm's tax return and financial statements, and what taxes it should be paying the IRS. Uncertainty also exists for a firm regarding the applicability of relevant tax legislation or case law, the anticipated actions of the IRS in terms of recognized tax benefits, and to publicly disclosed UTBs, including settlement amounts and the timing of those settlements.3 Management also faces considerable uncertainty concerning the assignment of probabilities in the computation of recognized tax benefits (FASB, 2006; Gupta, Laux, & Lynch, 2011; Lisowsky et al., 2013). In particular, the assignment of probabilities is imprecise, dependent on the facts, intent, and circumstances behind transactions or arrangements, and management experience and knowledge of the IRS's position about these transactions (FASB, 2006; De Simone & Stomberg, 2012). UTB estimates may also be subject to managerial opportunism (Hutchens & Rego, 2013).4

3 TAX AGGRESSIVENESS, EXTERNAL AUDIT, AND UNRECOGNIZED TAX BENEFITS

Recent studies explore the association between UTB estimates and tax aggressiveness (e.g., Lisowsky, 2010), the association between FIN48 disclosure requirements and tax aggressiveness (e.g., Robinson & Schmidt, 2013; Ciconte et al., 2016), and the association between UTB estimates and financial statement impacts, value-relevance or informativeness, including cash flows, stock prices, earnings, and firm-level risk (e.g., Gupta et al., 2011). Other studies on the subject of FIN48 have emphasized the considerable amount of judgment that management employs in the calculation of UTB estimates (e.g., De Simone & Stomberg, 2012).

Gleason and Mills (2011) assert that the external auditor can play an important role in terms of tax compliance and tax planning. For example, the external auditor can affect the computation of UTB estimates by an evaluation of a firm's tax returns, tax position working papers, and assessment of the likelihood of sustaining a series of tax benefits as a result of scrutiny of correspondence with the tax authorities (e.g., IRS), review of tax audits and settlement outcomes and timing, risk analysis (e.g., risk tolerance of the client), and the riskiness of UTPs. The application of tax legislation, legal intent of transactions, and an assessment of probabilities assigned to tax benefits can also vary based on the skill, expertise, and resources of the external auditor (Gleason & Mills, 2011).

Beck and Lisowsky (2014) examine the association between UTB estimates (as a measure of tax uncertainty) and a firm's voluntary participation in the IRS's compliance assurance process (CAP) audit program.5 They find that firms that participate in CAP have moderate rather than small or large levels of UTBs compared with non-CAP firms. Beck and Lisowsky (2014) also find that firms which participate in CAP, on average, obtain larger reductions in UTBs in comparison with non-CAP firms. This study provides evidence that perceived effectiveness of the IRS and audit risk can play an important role in managements' derivations of UTB estimates.

Donohoe and Knechel (2014) claim that the positive association between tax aggressiveness and audit fees is a likely result of complex and uncertain tax arrangements that, in turn, give rise to large UTB estimates. Audits of tax-aggressive firms require additional audit effort as tax advice is likely to be sought from a broad range of consultants, such as tax experts, lawyers, economists, finance and corporate structure, and supply chain experts. In fact, increased audit effort may assist in establishing a more complete picture of a firm's UTB estimates based on economic and reputational risks (Lisowsky, 2010).

Armstrong, Blouin, and Larcker (2012) find that the higher the proportion of tax fees provided by the auditor, the lower the level of a firm's effective tax rate. This result suggests that auditors that also provide tax-related services can use their joint knowledge of a firm's financial accounting and tax reporting/planning and underlying operational conditions to develop successful tax strategies with the result of significantly lowering the amount of corporate taxes payable. As prior research has provided strong evidence that UTBs are an effective proxy of a firm's tax avoidance or tax sheltering activities (e.g. Blouin et al., 2012; Hutchens & Rego, 2013; Lisowsky et al., 2013; Neuman et al., 2013; Rego & Wilson, 2012), it is likely that tax arrangements will be inherently more riskier and uncertain, resulting in larger UTB estimates.6

As there is a considerable amount of latitude in the calculation of a firm's UTB estimates, we conjecture that income-shifting arrangements dealing with transfer pricing aggressiveness, tax haven use, and foreign tax rate differentials that involve a high degree of tax complexity and uncertainty are expected to significantly affect management's estimates of UTBs. We also conjecture that audit specialization is likely to significantly impact the association between income shifting arrangements and UTBs.

4 HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

4.1 Income-shifting arrangements and unrecognized tax benefits—H1

Income-shifting arrangements generally comprise transfer pricing aggressiveness, the use of tax havens, and exploitation of arbitrage opportunities based on foreign tax rate differentials (Klassen & Laplante, 2012a, 2012b).

Transfer pricing aggressiveness is considered by the IRS to be an important area that has contributed toward a significant reduction in the payment of taxes by multinational firms (, 2013a; , 2013b; IRS, 2010). Recent media releases on aggressive transfer pricing arrangements carried out by US multinational firms provide evidence of the substantial tax benefits derived by these firms from taking advantage of differences in tax law, tax rates, and regulatory conditions between jurisdictions, and the non-arm's-length pricing of goods, services and funds transferred amongst related parties (Grubert, 2003; Grubert & Mutti, 1991; Levin, 2012; Usmen, 2012).

The nature of the transfer pricing arm's-length standard, pursuant to section 482 of the Internal Revenue Code, the supporting Treasury Regulations, and the variability in county-specific transfer pricing rules, provides unique challenges in the application of FIN48 (The Treasury, 2007). Transfer-pricing documentation reports require a firm to have sufficient evidence based on standards of reasonableness to substantiate its arms-length pricing7 and transfer of goods, funds and services between group affiliates.8 The fundamental principle behind transfer pricing is that intra-group transactions should be conducted on normal commercial terms or on an arm's-length basis reflective of the pricing of similar transactions between independent entities under similar conditions. Owing to the inherent difficulty in ensuring that a firm's arrangements are at arm's length, management is faced with uncertainty in deciding whether a firm's tax position can be sustained following IRS examination (Borkowski & Gaffney, 2012).9 If intra-group affiliates do have transfer pricing arrangements, the entity may record in its tax return the tax benefits stemming from related party transactions. A UTB ensues because a lower amount of income or higher amount of cost is recorded by one or more group affiliates which the entity believes it can justify following IRS examination. Although the tax benefit (e.g., interest deductions) is more likely than not to be sustained following audit examination, the full amount of the benefit is uncertain because of the subjectivity involved in valuing related-party transactions and the method adopted. The reason for this is that, potentially, the full amount of the tax benefit may be reversed upon audit by the IRS.

Income shifting via the exploitation of foreign tax rate differentials is another area that is likely to lead to much uncertainty for a firm in terms of tax planning and compliance. Grubert and Mutti (1991) find that US firms report more income in low-tax jurisdictions compared with high-tax jurisdictions. Klassen, Lang, and Wolfson (1993) show that income shifting, due to tax rate changes relative to that of the USA in the 1980s, was around 10–20% of income to/from US firms. Jacob (1996) claims that firms operating among several jurisdictions with different corporate tax rates have more opportunities to achieve tax savings by locating income in low-tax jurisdictions and locating deductible expenses (e.g., interest on debt) in high-tax jurisdictions. Klassen and Laplante (2012a, 2012b) find that firms can shift income between group subsidiaries located in variably taxed jurisdictions by transfer pricing, strategic debt placement, and preferential cost allocation. Foreign tax rate differentials are recorded in effective tax rate reconciliation statements when a significant (i.e., greater than 5%) amount of income is “earned” in offshore jurisdictions that attract tax rates less than the US statutory tax rate of 35%. A firm's exposure to tax uncertainty occurs when it includes in its tax filing the benefit received from transactions where the firm is able to reduce its group taxes by strategically allocating income to lower tax jurisdictions, which may also include tax havens. The foreign tax differential reflects the weighted average effect of lower tax rates applied to permanently reinvested foreign-sourced income. Tax uncertainty occurs because a firm needs to discern whether earnings are in fact permanently reinvested and a lower foreign tax is applied, or whether some or all of those earnings are not permanently reinvested and would therefore be taxed at the US statutory tax rate. The foreign tax differential also reflects that the firm is exposed to multiple sets of tax laws and rates across the countries that it operates in, and this is often reflected by disclosures made by the firm that it is unable to record deferred taxes on earnings held or made offshore. Although a benefit is generally more likely than not to result from such an arrangement (e.g., some amount will be allowed for deriving income in a specific low-tax jurisdiction where the income is considered to be permanently reinvested in that jurisdiction), the amount of benefit is often uncertain due to the subjectivity and complexity involved in determining exactly how much of that foreign income is to be permanently reinvested.

The role of tax havens in assisting with the economic, financing, and taxation arrangements of a firm has gained a lot of attention in recent years and is a major area of focus by the IRS (2010), 2013a).10 Dyreng and Lindsey (2009) find that US firms which disclosed material operations in at least one tax haven country have an average worldwide tax rate on pre-tax worldwide income that is around 1.5 percentage points lower than firms without operations in at least one tax haven country. Prior research also documents that tax haven use is positively associated with tax aggressiveness (e.g., Desai, Dyck, & Zingales, 2007; Desai, Foley, & Hines, 2006a; Dharmapala, 2008; Dharmapala & Hines, 2009). Complex arrangements involving the use of tax havens for these purposes are thus likely to significantly impact a firm's tax planning and tax compliance activities, with flow-on effects on the calculation of a firm's tax position and UTB estimates. These jurisdictions may augment the uncertainty in deriving tax benefits from earnings held and taxed offshore as tax havens are usually characterized by nil or only nominal tax rates. Thus, tax haven use may exacerbate the foreign tax rate differential recorded in accounting to taxable income reconciliations. The uncertainty in derivation of this tax benefit may also be enhanced by the lack of information exchange and the secrecy behind transactions conducted through tax havens, and the uncertainty created by close examination of tax haven use by the IRS and the media. Again, while the tax benefit derived from tax haven use is more likely than not, the total amount of tax benefits is uncertain.

To formally test the impact of each of the aforementioned income-shifting elements on UTB estimates, we develop the following (directional) hypothesis:

H1.All else equal, income-shifting arrangements (i.e., transfer pricing aggressiveness, tax haven use, and foreign tax rate differentials) are positively associated with UTBs.

4.2 The impact of audit specialization on the association between income-shifting arrangements and unrecognized tax benefits—H2

We also conjecture that audit specialization could impact the association between income-shifting arrangements and UTB estimates.

On the one hand, it is possible that audit specialization could magnify the positive association between income-shifting arrangements and UTBs. Specifically, many new challenges arise in a FIN48 environment as tax-aggressive positions are expected to create additional audit risk and audit effort. These elements are likely to be exacerbated where a firm's tax positions are highly uncertain in nature, and significant subjectivity is involved in forming a particular tax view. Thus, audit specialists may adopt a cautionary stance, and through their additional insights into a firm's operations require that it record more or even larger UTB estimates. The reason for this is that FIN48 recognition, measurement, and disclosure requirements have introduced a major source of financial reporting risk for a firm and its auditor (Graham, Raedy, & Shackelford, 2012; Donohoe & Knechel, 2014). The complexities and judgments required in the calculation of a firm's tax position require the engagement of well-informed specialized auditors. Thus, specialist auditors may ensure that large UTB estimates are recorded against income-shifting arrangements given the audit risk imposed by them. Further, audit specialists may also promote and initiate aggressive tax planning strategies, leading a firm to claim larger tax benefits on its tax filings, thereby increasing the level of tax uncertainty and UTB estimates recorded in the financial statements.11

Alternatively, it is also possible that audit specialization could moderate the positive association between income-shifting arrangements and UTBs. Prior research shows that audit specialization through industry expertise of audit firms generates higher quality audits and enhances the credibility of financial statements (e.g., Audousset-Coulier, Jeny, & Jiang, 2016; Dunn & Maydew, 2004; Ho & Kang, 2013; Reichelt & Wang, 2010).12 In a similar way to the development of financial statement audit expertise, audit firms may acquire tax expertise in terms of specific industry sectors based on knowledge of their operations, investing and financing activities, growth opportunities, and earnings strategies. Specialist auditors are then able to develop specific arrangements or transactions using industry-sector knowledge to reduce the uncertainty about a firm's tax benefits.13 The implementation of an effective income-shifting arrangement through the use of specialist auditors may, therefore, mitigate the risk that large UTBs accrue because of the complex nature of such arrangements. It is also conceivable that audit and tax-related industry expertise work simultaneously toward assisting a firm in reducing its tax liabilities as a result of the interrelationship between financial accounting and income tax provisions, especially in terms of the assessment of the commerciality or arm's-length nature of arrangements and transactions, and FIN48 reporting requirements (Maydew & Shackelford, 2007). This conjecture is also supported by prior studies that emphasize a knowledge spillover effect whereby knowledge and skills built up in one area (e.g., financial accounting and audit) can be channeled to and used in another area (e.g., tax planning and compliance) or vice versa, or in the identification of tax uncertainties dealing with complex tax issues (Donohoe & Knechel, 2014). Hence, it is possible that specialist auditors in both tax and financial accounting could serve to moderate the prospect that large UTBs will result as a result of income-shifting arrangements.

Ultimately, it is an empirical question as to whether audit specialization magnifies or moderates the positive association between income-shifting arrangements and UTBs. To formally test the impact of audit specialization on the association between income-shifting arrangements and UTBs, we develop the following (nondirectional) hypothesis:

H2.All else equal, audit specialization magnifies/moderates the positive association between income- shifting arrangements (i.e., transfer pricing aggressiveness, tax haven use, and foreign tax rate differentials) and UTBs.

5 RESEARCH DESIGN

5.1 Sample selection and data source

Our sample initially comprised of S&P 50014 publicly-listed firms over the 2007–2016 period.15 The sample was then reduced to 286 firms (2,097 firm-year observations) after excluding financial and insurance firms (47 firms) and firms that do not have any overseas subsidiaries (167 firms). Financial institutions and insurance firms were excluded from the sample due to significant differences in the application of accounting policies and the derivation of accounting estimates, together with the different regulatory constraints faced by these firms. We focus our attention on multinational firms in this study, as these firms are more likely to have the capacity and opportunity to engage in financial and taxation arbitrage across multiple jurisdictions and to experience significant uncertainties in terms of the derivation and sustainability of their tax positions (Dyreng & Lindsey, 2009; Lisowsky et al., 2013). Finally, financial data were collected from Compustat, where possible. However, UTB estimates, transfer pricing, tax haven, income shifting, and R&D tax credit data were hand collected from a firm's 10-K annual report.

Table 1 reports sample distributions based on year and industry based on the Fama and French (1997) 12 industry sector classification (FF12). We find that our sample includes a greater proportion of firms in the manufacturing (19.41%), computers (19.27%), oil and gas (10.30%), other (10.25%), and healthcare sectors (10.06%) than in the other industry sectors. Nevertheless, there appears to be no significant industry bias considering the nature of our sample.

| FF12 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Total | Relative freq. (%) | |

| 1. | Chemicals | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 146 | 7.00 |

| 2. | Computers | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 40 | 40 | 41 | 25 | 404 | 19.27 |

| 3. | Consumer durables | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 83 | 3.96 |

| 4. | Consumer nondurables | 20 | 20 | 20 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 13 | 187 | 8.92 |

| 5. | Healthcare | 19 | 20 | 21 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 24 | 17 | 211 | 10.06 |

| 6. | Manufacturing | 39 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 42 | 42 | 38 | 407 | 19.41 |

| 7. | Oil and gas | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 18 | 216 | 10.30 |

| 8. | Other | 20 | 22 | 21 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 17 | 215 | 10.25 |

| 9. | Media | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 19 | 0.86 |

| 10. | Utilities | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 30 | 1.43 |

| 11. | Wholesale and retail | 20 | 20 | 19 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 19 | 10 | 179 | 8.54 |

| Totals | 211 | 216 | 215 | 211 | 214 | 217 | 215 | 216 | 218 | 164 | 2097 | 100.00 |

5.2 Dependent variable

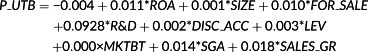

(1)

(1)Our first measure of UTBs focuses on whether the magnitude of the actual UTB deviates significantly from the expected value of the UTB and the amount of under- or overreserving of that tax liability (AUTB_PUTB). We are then able to quantify whether abnormal UTB amounts (i.e., where there is under- or overreserving) are associated with a particular area of income shifting. Lisowsky et al. (2013) argue that an underestimation of UTB (i.e., actual UTB less than expected UTB) may occur if a firm wants to reduce the amount of information reported to the IRS or engages in particularly aggressive tax avoidance activities.

Our second measure of UTBs is a dichotomous variable coded as 1 if actual UTB is greater than expected UTB, or 0 otherwise (AUTB > PUTB). Lisowsky et al. (2013) claim that an overestimation of UTB (i.e., actual UTB greater than expected UTB) may occur if a firm's actual engagement in risky tax avoidance activities exceeds that captured through a predicted UTB measure.

Our third measure of UTBs is denoted as the natural logarithm of unrecognized tax benefits (UTB_LN), while our fourth measure of UTBs is represented as unrecognized tax benefits scaled by total assets (UTB_TA), both consistent with those used in prior research (e.g., Beck & Lisowsky, 2014; Ciconte et al., 2016).

Finally, we note that as a result of applying FIN48, the UTBs or the difference between a tax position taken (or expected to be taken) in a firm's tax return and the benefit recognized as per FIN48 are required to be disclosed in its annual report (FASB, 2006). Specifically, FIN48 requires a firm to disclose the annual roll-forward of all UTBs set out in the form of a reconciliation of the beginning and ending balances of UTBs on a worldwide aggregate basis (FASB, 2006).18

5.3 Independent variables

5.3.1 Income-shifting measures

Our first set of independent variables contains by three income-shifting arrangements: transfer pricing aggressiveness (TPMIS), tax haven use (THAV), and foreign tax rate differentials (FTRD).

TPMIS is measured in this study as a dummy variable, coded as 1 if there is evidence in a firm's annual report that group affiliates have mispriced transferred goods, services and/or associated payments, or 0 otherwise. Therefore, TPMIS is determined in our study based on the mispricing of transferred goods, services, and/or associated payments between group affiliates.19 Evidence of the mispricing of goods and services can be found from legal action between a firm and various government agencies (e.g., the Department of Justice or the IRS) or between a firm and third-party firms about the mispricing of goods or services between group affiliates that affect dealings with third parties. Further evidence is provided in cases where a firm is subject to a transfer pricing audit by the IRS (or other tax authority) and the nature of the dispute deals with the arm's-length pricing of goods and services.20

THAV is measured in this study as a dummy variable, coded as 1 if a firm has at least one subsidiary firm incorporated in an OECD (2006) listed tax haven, or 0 otherwise (Desai, Foley, & Hines, 2006b). The occurrence of material tax haven operations for each firm in our sample is determined from a listing of subsidiaries and country of incorporation in Exhibit 21 of the 10-K annual report. The THAV variable measures a firm's use of jurisdictions with either no or negligible amounts of corporate taxes.

FTRD is measured in this study based on the net effect of US and foreign tax rate differentials as per prior research (e.g., Huizinga & Laeven, 2008). We evaluate the net marginal tax effect of different US foreign tax rates on prima facie income tax expense on accounting income.21 A US firm's foreign earnings are generally taxed at a lower rate than the US statutory tax rate of 35%, which results in negative adjustments to income tax expense. Large absolute adjustments to income tax expense on accounting profit due to net differential foreign tax rates are likely to reflect greater incentives for a firm to engage in income shifting (Huizinga & Laeven, 2008).22

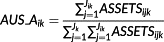

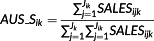

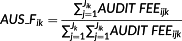

5.3.2 Audit specialization measures

Our second set of independent variables comprises audit specialization (AUS) and interaction terms between audit specialization and each of the three income-shifting arrangements (AUS*TPMIS, AUS * THAV, and AUS * FTRD). Audousset-Coulier et al. (2016) claim that the choice of an audit specialization23 model and the setting can affect the consistency and significance of findings, and any inferences drawn on the provision of audit services by auditors in their capacity as specialists. They also argue that the choice of an auditor specialization model including the metrics employed for each model used, is dependent upon the research question being answered. Consequently, to improve the robustness of our empirical results, we use three proxy measures of audit specialization in our study based on the three largest portfolio share approach of Audousset-Coulier et al. (2016).24 In this study, AUS_A denotes audit specialization based on the top three clients by size as measured by a client's total assets; AUS_S represents audit specialization based on the top three clients by size as measured by a client's total sales; and AUS_F denotes audit specialization based on the top three clients measured by a client's audit fees.25

(2)

(2) (3)

(3) (4)

(4)Finally, each of the audit specialization models for the empirical analysis is then measured as a dummy variable, coded as 1 if the audit firm is in the top three based on assets of the client (AUS_A), sales revenue of the client (AUS_S), and audit fees of the client (AUS_F) in a particular industry and year, or 0otherwise (see Audousset-Coulier et al., 2016).

5.4 Control variables

Our study also includes a number of control variables: nonaudit tax fees (NATF), firm size (SIZE), profitability (PROFIT), leverage (LEV), intangible assets (INTANG), capital intensity (CINT), net operating loss carryforwards (NOL), the market-to-book ratio (MKTBK), industry sector (INDSEC), and year (YEAR) effects.

Nonaudit tax service fees (NATF) of an auditor are included in our regression models to control for the level of tax planning and the complexity of the tax positions taken by a firm. Lim and Tan (2007) claim that specialist auditors are likely to suffer reputation loss and litigation exposure, and also to benefit from knowledge spillover effects from the provision of nonaudit services. NATF is measured as the natural logarithm of nonaudit tax fees provided to the auditor. Large firms are expected to record higher UTB estimates as they tend to engage in more complex tax arrangements involving many facets of tax law, so they have higher tax compliance and planning costs (Lassila & Smith, 1997; Lisowsky et al., 2013). We expect NATF to have a positive sign.

SIZE is measured in this study as the natural logarithm of total assets (Porcano, 1986). SIZE is expected to have a positive sign.

The uncertainty of a firm's future profitability is likely to increase its level of tax aggressiveness (Hutchens & Rego, 2013). Hutchens and Rego (2013) find that the level of a firm's UTB balance is significantly positively associated with the cost of equity capital. PROFIT is measured as the natural logarithm of pre-tax income (Rego, 2003), and is expected to have a positive sign.

Highly leveraged firms that engage in aggressive and risky tax arrangements have a higher level of uncertainty in terms of the recognition of tax benefits, which may lead to higher UTB estimates (Lisowsky et al., 2013). LEV is measured as long-term debt scaled by total assets (Gupta & Newberry, 1997). We expect LEV to have a positive sign.

The lack of well-established markets and subjective valuations of intangible assets transferred between group affiliates across variably taxed jurisdictions may result in higher UTB estimates (Gravelle, 2010). INTANG is measured as the natural logarithm of intangible assets (Dyreng, Hanlon, & Maydew, 2008), and is expected to have a positive sign.

Highly capital-intensive firms are likely to be subject to a more complex operating and tax environment and have higher tax planning costs (Lassila, Omer, Shelley, & Smith, 2010; Mills, Erickson, & Maydew, 1998) leading to higher UTB estimates. CINT is measured as net property, plant, and equipment scaled by total assets (Stickney & McGee, 1982). We expect CINT to have a positive sign.

There are also tax uncertainties regarding the ability of a firm to derive sufficient taxable income to offset its tax losses, which could affect the recognition of its tax benefits and UTB balance (Dyreng et al., 2008). NOL is measured as a dummy variable, coded as 1 where a firm has net operating loss carryforwards, or 0otherwise, and NOL is expected to have a positive sign.

Firms with higher growth or investment opportunities are likely to be affected by a more complex tax environment due to the purchase of tax-favored assets (e.g., Chen, Chen, Cheng, & Shevlin, 2010) and may lead to higher UTB estimates. We measure MKTBK as the market value of equity scaled by the book value of equity (Frank, Lynch, & Rego, 2009). We expect MKTBK to have a positive sign.

Industry-sector (INDSEC) dummy variables, based on the FF12 classification, are included as control variables in this study because it is likely that tax complexity and tax planning vary across industry sectors (Rego, 2003).28 No sign predictions are made for the INDSEC dummies.

Finally, we incorporate year dummy variables (YEAR) as control variables in our study to control for the differences in UTBs or other activities that could have potentially existed over the 2007–2012 sample years. No sign predictions are made for the YEAR dummies.

5.5 Regression models

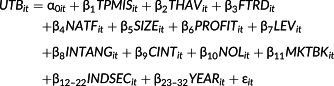

(5)

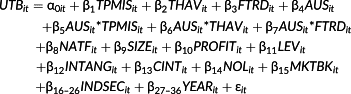

(5) (6)

(6)6 EMPIRICAL RESULTS

6.1 Descriptive statistics

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics for the dependent variables (AUTB_PUTB, AUTB > PUTB, UTB_LN, and UTB_TA), independent variables (TPMIS, THAV, FTRD, AUS_A, AUS_S, and AUS_F), and control variables (NATF, SIZE, PROFIT, LEV, INTANG, CINT, NOL, and MKTBK). The dependent variables AUTB_PUTB, AUTB > PUTB, UTB_LN, and UTB_TA have means (medians) of 3.500 (3.483), 0.848 (1.000), 3.404 (3.444), and 0.011 (0.007) respectively. The independent variable TPMIS has a mean of 0.134, indicating that approximately 13.4% of the sample firms have group affiliates with mispriced transferred goods, services, and/or associated payments. THAV has a mean of 0.798, showing that around 79.8% of the firms have at least one subsidiary firm incorporated in an OECD (2006) listed tax haven. FTRD has a mean of 4.910, indicating that US multinational firm's foreign earnings are taxed, on average, at approximately 5% less than the US statutory tax rate of 35%. Finally, the mean, median, and range of all of the control variables employed in this study are also shown in Table 2.

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | 0.25 | Median | 0.75 |

| AUTB_PUTB | 2097 | 3.500 | 2.294 | 1.884 | 3.483 | 5.006 |

| AUTB>PUTP | 2097 | 0.848 | 0.359 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| UTB_LN | 2097 | 3.404 | 2.298 | 1.639 | 3.444 | 4.943 |

| UTB_TA | 2097 | 0.011 | 0.013 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.016 |

| TPMIS | 2097 | 0.134 | 0.341 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| THAV | 2097 | 0.798 | 0.401 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| FTRD | 2097 | 4.910 | 2.098 | 3.566 | 4.942 | 6.260 |

| AUS_A | 2097 | 0.846 | 0.361 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| AUS_S | 2097 | 0.848 | 0.359 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| AUS_F | 2097 | 0.854 | 0.353 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| NATF | 2097 | 0.503 | 0.571 | 0.060 | 0.292 | 0.744 |

| SIZE | 2097 | 8.663 | 1.710 | 7.334 | 8.525 | 10.005 |

| PROFIT | 2097 | 0.365 | 0.636 | 0.216 | 0.319 | 0.442 |

| LEV | 2097 | 0.249 | 0.172 | 0.133 | 0.237 | 0.347 |

| INTANG | 2097 | 0.234 | 0.223 | 0.049 | 0.179 | 0.356 |

| CINT | 2097 | 7.906 | 1.838 | 6.583 | 7.723 | 9.398 |

| NOL | 2097 | 0.906 | 0.292 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| MKTBK | 2097 | 3.193 | 3.879 | 1.587 | 2.451 | 3.825 |

- Variable definitions: AUTB_PUTB is the difference between the actual UTB amount and the predicted UTB amount; AUTB > PUTP is a dummy variable, coded as 1 if actual UTB greater than expected UTB, or 0 otherwise; UTB_LN is the natural logarithm of unrecognized tax benefits; UTB_TA is unrecognized tax benefits scaled by total assets; TPMIS is a dummy variable, coded as 1 if there is evidence within the annual report that group affiliates have mispriced transferred goods, services, and/or associated payments, or 0 otherwise; THAV is a dummy variable, coded as 1 if a firm has at least one subsidiary firm incorporated in an OECD (2006) listed tax haven, or 0 otherwise; FTRD is the net marginal tax effect of different foreign tax rates on prima facie income tax expense on accounting income; AUS_A is audit specialization based on the top three clients by size, as measured using a client's total assets; AUS_S is audit specialization based on the top three clients by size, as measured using a client's total sales; AUS_F is audit specialization based on the top three clients by size, as measured using a client's total audit fees; each of the audit specialization models is then measured as a dummy variable, coded as 1 if the audit firm is in the top three based on assets of the client (AUS_A), sales revenue of the client (AUS_S), and audit fees of the client (AUS_F) in a particular industry and year, or 0 otherwise; NATF is the natural logarithm of nonaudit tax fees; SIZE is the natural logarithm of total assets; PROFIT is the natural logarithm of pre-tax income; LEV is total liabilities scaled by total assets; INTANG is the natural logarithm of intangible assets; CINT is net property, plant, and equipment scaled by total assets; NOL is a dummy variable, coded as 1 where a firm has net operating loss carryforwards, or 0 otherwise; and MKTBK is the market value of equity scaled by the book value of equity.

6.2 Correlation results

The Pearson correlation results are shown in Table 3. Significant correlations are found between AUTB_PUTB, AUTB > PUTB, UTB_LN, and UTB_TA and the independent variables TPMIS, THAV, and FTRD (mostly at p < .01) and the control variables NATF, SIZE, PROFIT, LEV, INTANG, CINT, NOL, and MKTBK (p < .05 or better). Table 3 generally reports moderate levels of collinearity between the explanatory variables employed in this study. However, the highest correlation coefficient of .918 is found between SIZE and CINT (p < .01), so we computed variance inflation factors when estimating our regression models to test for signs of multicollinearity between the explanatory variables. Our (untabulated) results show that none of the variance inflation factors exceed 5 for any of our explanatory variables, so multicollinearity does not present a problem in our study (e.g., Kutner, Nachtsheim, & Neter, 2004).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | ||

| 1 | AUTB_PUTB | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||

| 2 | AUTB > PUTP | .359*** | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| 3 | UTB_LN | .866*** | .509*** | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| 4 | UTB_TA | .550*** | .352*** | .615*** | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| 5 | TPMIS | .264*** | .049** | .233*** | .199*** | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 6 | THAV | .233*** | .147*** | .230*** | .195*** | −.046** | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 7 | FTRD | .676*** | .086*** | .578*** | .188*** | .234*** | .146*** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 8 | NATF | .324*** | .098*** | .301*** | .153*** | .117*** | .142*** | .251*** | 1.000 | |||||||

| 9 | SIZE | .782*** | .097*** | .652*** | .118*** | .238*** | .138*** | .817*** | .310*** | 1.000 | ||||||

| 10 | PROFIT | .065*** | .007 | .065*** | −.009 | .044** | −.007 | .088*** | .030 | .093*** | 1.000 | |||||

| 11 | LEV | .211*** | .069*** | .199*** | −.080*** | .021 | .060*** | .149*** | .108*** | .302*** | .143*** | 1.000 | ||||

| 12 | INTANG | .070*** | .025 | .112*** | .075*** | .130*** | .083*** | .028 | .204*** | .059*** | .027 | .342*** | 1.000 | |||

| 13 | CINT | .681*** | .079*** | .549*** | .030 | .147*** | .069*** | .735*** | .233*** | .918*** | .097*** | .300*** | −.148*** | 1.000 | ||

| 14 | NOL | .067*** | .104*** | .077*** | .074*** | −.076*** | .216*** | −.006 | .087*** | .042* | −.008 | .116*** | .083*** | .025 | 1.000 | |

| 15 | MKTBK | .038* | −.017 | .037* | .015 | .057*** | .012 | .104*** | .055** | .048** | .777*** | .111*** | .049** | .021 | .002 | 1.000 |

- *, **, and, *** indicate statistical significance at the .10, .05, and .01 levels respectively. The p-values are one-tailed for directional hypotheses and two-tailed otherwise.

- N = 2097 for all variables.

- Variable definitions: all variables are defined in Table 2.

6.3 Regression results: income-shifting arrangements and unrecognized tax benefits (H1)

The base regression model results in terms of testing H1 are presented in Table 4. We note that the p-values are one-tailed for directional hypotheses and two-tailed otherwise, and are computed based on standard errors which are clustered at the firm-level (Petersen, 2009). The coefficients for industry sector and year effects are not reported for the sake of brevity.

| Variables | Predicted sign | AUTB_PUTB(OLS) | AUTB > PUTB(Logit) | UTB_LN(OLS) | UTB_TA(OLS) |

| TPMIS | + | 0.4258 | 0.4118 | 0.0044 | 0.4151 |

| (2.17)** | (1.07) | (1.92)** | (1.59)* | ||

| THAV | + | 0.6314 | 0.8554 | 0.0044 | 0.7349 |

| (3.71)*** | (2.96)*** | (3.39)*** | (3.26)*** | ||

| FTRD | + | 0.0835 | 0.0575 | 0.0012 | 0.1074 |

| (2.35)** | (0.72) | (3.18)*** | (2.90)*** | ||

| NATF | + | 0.0266 | 0.0262 | 0.0002 | 0.0268 |

| (1.96)** | (1.18) | (1.70)* | (1.76)** | ||

| SIZE | + | 1.0181 | −0.1906 | −0.0001 | 0.8139 |

| (7.62)*** | (−0.88) | (−0.06) | (5.42)*** | ||

| PROFIT | + | −0.0017 | 0.4301 | 0.0000 | 0.1728 |

| (−0.02) | (2.42)** | (0.02) | (1.26) | ||

| LEV | + | 0.0267 | 0.6216 | −0.0061 | 0.2682 |

| (0.07) | (0.91) | (−1.65)* | (0.53) | ||

| INTANG | + | −0.4849 | −0.2525 | −0.0001 | −0.0679 |

| (−1.49)* | (−0.45) | (−0.02) | (−0.18) | ||

| CINT | + | −0.0691 | 0.2474 | −0.0002 | −0.0683 |

| (−0.55) | (1.31)* | (−0.18) | (−0.52) | ||

| NOL | + | −0.0103 | 0.3458 | 0.0010 | 0.0968 |

| (−0.06) | (0.88) | (0.66) | (0.35) | ||

| MKTBK | + | −0.0071 | −0.0895 | −0.0000 | −0.0356 |

| (−0.34) | (−2.74)*** | (−0.21) | (−1.24) | ||

| Constant | ? | −6.2702 | −1.7103 | −0.0005 | −5.6242 |

| (−13.66)*** | (−1.89)* | (−0.13) | (−8.97)*** | ||

| INDSEC | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YEAR | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| Adj. R2 | 0.666 | 0.158 | 0.179 | 0.519 | |

| N | 2097 | 2097 | 2097 | 2097 |

- *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the.10, .05, and .01 levels respectively. The p-values are one-tailed for directional hypotheses and two-tailed otherwise, and are calculated based on standard errors that are clustered at the firm-level (Petersen, 2009).

- OLS, ordinary least squares.

- Variable definitions: all variables are defined in Table 2.

Table 4 shows that the TPMIS coefficient is positively and significantly associated with AUTB_PUTB and UTB_LN (p < .10 or better), providing support for H1. This result confirms our conjecture that aggressive transfer pricing activities which may depart from arm's-length intercompany pricing are likely to generate larger UTB estimates, as a greater proportion of the tax benefit provided on a firm's tax returns is not likely to be sustained following IRS examination. In addition, aggressive transfer pricing activities are likely to increase the magnitude of the difference between actual and predicted UTB estimates. The THAV coefficient is positive and significantly associated with AUTB_PUTB, AUTB > PUTB, UTB_LN, and UTB_TA (p < .01), supporting H1. Complex and obscure arrangements involving the use of tax havens significantly impact a firm's tax position and UTB estimates. The FTRD coefficient is positively and significantly associated with AUTB_PUTB, UTB_LN, and UTB_TA (p < .05 or better), providing support for H1. Where a firm participates in aggressive income-shifting arrangements, it generates a substantial amount of uncertainty regarding its tax position and UTB estimates.

Table 4 also reports that some of the control variable coefficients are statistically significant (with predicted signs). For instance, the NATF coefficient is positively and significantly associated with AUTB_PUTB, UTB_LN, and UTB_TA (p < .10 or better) (Lassila & Smith, 1997). The SIZE coefficient is positively and significantly associated with AUTB_PUTB and UTB_TA (p < .01), indicating that large firms are more likely to record higher UTB estimates (Lisowsky et al., 2013). The PROFIT coefficient is positively and significantly associated with AUTB > PUTB (p < .01), showing that profitable firms have more aggressive tax positions (Rego & Wilson, 2012) in the form of larger differences positively and significantly associated with AUTB_PUTB (p < .10), as expected (Mills et al., 1998).

6.4 Regression results: the impact of audit specialization on the association between income-shifting arrangements and unrecognized tax benefits (H2)

Our extended regression model results for the potential impact of audit specialization on the association between income-shifting arrangements and UTBs (H2) are presented in Table 5.

| Variables | Predicted sign | AUTB_PUTB(OLS) | AUTB > PUTB(Logit) | UTB_LN(OLS) | UTB_TA(OLS) |

| Panel A: Audit specialization—audit market share based on assets (AUS_A) | |||||

| TPMIS | + | 0.0477 | 0.9960 | −0.3360 | −0.0011 |

| (0.23) | (0.89) | (−1.25) | (−0.48) | ||

| THAV | + | 0.4909 | 2.2653 | 0.5117 | 0.0031 |

| (2.67)*** | (3.91)*** | (3.31)*** | (2.37)** | ||

| FTRD | + | 0.0359 | −0.3181 | 0.0462 | 0.0012 |

| (0.78) | (−2.10)** | (0.89) | (2.85)*** | ||

| AUS_A | ? | −0.4545 | −1.8845 | −0.6895 | −0.0008 |

| (−2.24)** | (−2.76)*** | (−3.21)*** | (−0.40) | ||

| AUS_A*TPMIS | ? | 0.4458 | 0.9563 | 0.8892 | 0.0066 |

| (1.95)** | (0.72) | (2.93)*** | (2.63)*** | ||

| AUS_A*THAV | ? | 0.1939 | −1.1535 | 0.3050 | 0.0015 |

| (0.94) | (−1.80)* | (1.64) | (1.09) | ||

| AUS_A*FTRD | ? | 0.0547 | 0.4938 | 0.0681 | −0.0001 |

| (1.14) | (3.51)*** | (1.24) | (−0.25) | ||

| NATF | + | 0.0270 | 0.0279 | 0.0274 | 0.0002 |

| (3.90)*** | (1.30)* | (3.67)*** | (3.46)*** | ||

| SIZE | + | 1.0299 | −0.1861 | 0.8384 | 0.0001 |

| (15.80)*** | (−0.99) | (12.26)*** | (0.14) | ||

| PROFIT | + | −0.0007 | 0.1464 | 0.1742 | 0.0001 |

| (−0.01) | (0.58) | (2.00)** | (0.12) | ||

| LEV | + | 0.0233 | 0.4915 | 0.2560 | −0.0060 |

| (0.11) | (0.78) | (1.08) | (−2.96)*** | ||

| INTANG | + | −0.4737 | −0.4846 | −0.0465 | −0.0001 |

| (−2.64)*** | (−0.83) | (−0.24) | (−0.05) | ||

| CINT | + | −0.0797 | 0.3329 | −0.0879 | −0.0004 |

| (−1.33)* | (1.98)** | (−1.48)* | (−0.74) | ||

| NOL | + | 0.0078 | 0.4927 | 0.1267 | 0.0012 |

| (0.08) | (1.67)* | (0.89) | (1.41)* | ||

| MKTBK | + | −0.0083 | −0.0360 | −0.0381 | −0.0001 |

| (−0.68) | (−0.73) | (−2.50)** | (−0.70) | ||

| Constant | ? | −5.9498 | 0.9563 | −5.1565 | −0.0000 |

| (−21.30)*** | (1.10) | (−15.56)*** | (−0.01) | ||

| INDSEC | ? | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| YEAR | ? | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Adj. R2 | 0.666 | 0.190 | 0.521 | 0.181 | |

| N | 2097 | 2097 | 2097 | 2097 | |

| Panel B: Audit specialization—audit market share based on sales (AUS_S) | |||||

| TPMIS | + | 0.0539 | −0.0076 | −0.3636 | −0.0013 |

| (0.26) | (−0.02) | (−1.02) | (−0.62) | ||

| THAV | + | 0.4667 | 1.3326 | 0.4232 | 0.0030 |

| (2.41)*** | (3.08)*** | (2.75)*** | (2.19)** | ||

| FTRD | + | 0.0350 | −0.2695 | 0.0744 | 0.0013 |

| (0.75) | (−2.12)** | (1.54)* | (2.97)*** | ||

| AUS_S | ? | −0.4340 | −1.7420 | −0.6050 | −0.0002 |

| (−2.06)** | (−3.13)*** | (−2.86)*** | (−0.09) | ||

| AUS_S*TPMIS | ? | 0.4539 | 0.5216 | 0.9339 | 0.0069 |

| (1.97)** | (0.96) | (3.01)*** | (2.89)*** | ||

| AUS_S*THAV | ? | 0.2110 | −0.4545 | 0.3930 | 0.0016 |

| (0.99) | (−0.98) | (2.14)** | (1.14) | ||

| AUS_S*FTRD | ? | 0.0516 | 0.3484 | 0.0224 | −0.0003 |

| (1.04) | (2.96)*** | (0.45) | (−0.56) | ||

| NATF | + | 0.0252 | 0.0295 | 0.0243 | 0.0002 |

| (3.68)*** | (1.97)** | (3.27)*** | (3.15)*** | ||

| SIZE | + | 1.0328 | −0.1198 | 0.8379 | −0.0002 |

| (14.86)*** | (−0.80) | (11.33)*** | (−0.32) | ||

| PROFIT | + | −0.0000 | −0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| (−0.36) | (−1.58)* | (0.06) | (1.15) | ||

| LEV | + | −0.0021 | 0.4085 | 0.2401 | −0.0058 |

| (−0.01) | (0.85) | (1.02) | (−2.90)*** | ||

| INTANG | + | −0.4339 | −0.0391 | 0.0135 | 0.0005 |

| (−2.43)** | (−0.09) | (0.07) | (0.33) | ||

| CINT | + | −0.0731 | 0.2811 | −0.0715 | −0.0003 |

| (−1.22) | (2.28)** | (−1.20) | (−0.57) | ||

| NOL | + | −0.0131 | 0.2881 | 0.0916 | 0.0011 |

| (−0.13) | (1.24) | (0.64) | (1.28) | ||

| MKTBK | + | −0.0004 | 0.0007 | −0.0003 | −0.0000 |

| (−1.39)* | (0.50) | (−0.78) | (−0.39) | ||

| Constant | ? | −6.0308 | −1.1178 | −5.3191 | 0.0008 |

| (−20.31)*** | (−1.54) | (−15.22)*** | (0.27) | ||

| INDSEC | ? | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| YEAR | ? | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Adj. R2 | 0.667 | 0.189 | 0.521 | 0.182 | |

| N | 2097 | 2097 | 2097 | 2097 | |

| Panel C: Audit specialization—audit fees (AUS_F) | |||||

| TPMIS | + | 0.0340 | 13.3874 | −0.1724 | −0.0023 |

| (0.16) | (28.11)*** | (−0.63) | (−1.15) | ||

| THAV | + | 0.4872 | 2.6429 | 0.6611 | 0.0030 |

| (2.63)*** | (4.22)*** | (4.00)*** | (2.27)** | ||

| FTRD | + | 0.0356 | 0.2448 | 0.0151 | 0.0011 |

| (0.79) | (1.70)** | (0.27) | (2.59)*** | ||

| AUS_F | ? | −0.4240 | −1.1888 | −0.6250 | −0.0015 |

| (−2.05)** | (−1.89)* | (−2.79)*** | (−0.78) | ||

| AUS_F*TPMIS | ? | 0.4519 | −11.7882 | 0.6752 | 0.0078 |

| (1.95)* | (−15.36)*** | (2.21)** | (3.52)*** | ||

| AUS_F*THAV | ? | 0.1913 | −1.6789 | 0.1186 | 0.0017 |

| (0.93) | (−2.46)** | (0.61) | (1.23) | ||

| AUS_F*FTRD | ? | 0.0545 | 0.4210 | 0.1067 | 0.0000 |

| (1.16) | (3.21)*** | (1.79)* | (0.09) | ||

| NATF | + | 0.0269 | 0.0230 | 0.0271 | 0.0002 |

| (3.89)*** | (1.06) | (3.67)*** | (3.40)*** | ||

| SIZE | + | 1.0270 | −0.2340 | 0.8214 | 0.0000 |

| (15.79)*** | (−1.25) | (11.99)*** | (0.06) | ||

| PROFIT | + | 0.0001 | 0.1530 | 0.1767 | 0.0001 |

| (0.00) | (0.57) | (2.02)** | (0.10) | ||

| LEV | + | 0.0193 | 0.3636 | 0.2471 | −0.0060 |

| (0.09) | (0.58) | (1.04) | (−2.99)*** | ||

| INTANG | + | −0.4914 | −0.4232 | −0.0700 | −0.0003 |

| (−2.73)*** | (−0.72) | (−0.37) | (−0.22) | ||

| CINT | + | −0.0772 | 0.3700 | −0.0767 | −0.0004 |

| (−1.29) | (2.21)** | (−1.29) | (−0.68) | ||

| NOL | + | −0.0041 | 0.4997 | 0.1084 | 0.0011 |

| (−0.04) | (1.70)* | (0.75) | (1.23) | ||

| MKTBK | + | −0.0081 | −0.0330 | −0.0372 | −0.0001 |

| (−0.67) | (−0.64) | (−2.44)*** | (−0.67) | ||

| Constant | ? | −5.9446 | 0.5702 | −5.1283 | 0.0008 |

| (−21.05)*** | (0.68) | (−14.94)*** | (0.32) | ||

| INDSEC | ? | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| YEAR | ? | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Adj. R2 | 0.666 | 0.191 | 0.520 | 0.183 | |

| N | 2097 | 2097 | 2097 | 2097 | |

- *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the .10, .05, and .01 levels respectively. The p-values are one-tailed for directional hypotheses and two-tailed otherwise, and are calculated based on standard errors that are clustered at the firm level (Petersen, 2009).

- OLS, ordinary least squares.

- Variable definitions: AUS is audit specialization (proxied by AUS_A, AUS_S, and AUS_F), and AUS*TPMIS, AUS*THAV, and AUSZ*FTRD are the interaction terms between audit specialization and income-shifting arrangements (TPMIS, THAV, and FTRD); all other variables are defined in Table 2.

In terms of AUS_A (based on assets), Table 5, panel A, shows that the AUS_A*TPMIS coefficient is positively and significantly associated with AUTB_PUTB, UTB_LN, and UTB_TA (p < .05 or better), providing consistent support for H2. Table 5 (panel A) also shows that the AUS_A*THAV coefficient is significantly and negatively associated with AUTB > PUTB (p < .10). Given that a firm may employ tax havens for legitimate financing purposes (e.g., facilitating the flow of funds between corporate group members) (Dyreng & Lindsey, 2009) in addition to reducing corporate tax liabilities (Desai, 2003), audit specialization appears to reduce the magnitude of difference between actual and predicted UTBs, leading to a decrease in the estimate of UTBs. Finally, the AUS_A*FTRD coefficient is significantly and positively associated with AUTB > PUTB (p < .01), providing some support for H2. Overall, the findings for transfer pricing aggressiveness and foreign tax rate differential are particularly important here as they denote major areas of uncertainty for a firm (Klassen & Laplante, 2012a, 2012b), and are likely to be responsible for the large erosion of corporate tax revenues (Department of the Treasury, 2007). In fact, these results show that audit specialization increases the level of uncertainty associated with a firm's tax position that comprise transfer pricing or foreign tax rate differentials.

Table 5, panel B, reports the regression results for AUS_S, where audit specialization is based on the sales revenue of auditor clients. We observe that the AUS_S*TPMIS coefficient is significantly and positively associated with AUTB_PUTB, UTB_TA, and UTB_LN (p < .05 or better), furnishing consistent support for H2. We also find that the AUS_S*THAV coefficient is significantly and positively associated with UTB_LN (p < .05), and the AUS_S*FTRD coefficient is also significantly and positively associated with AUTB > PUTB (p < .01), furnishing additional support for H2. Taken together, these regression results are generally consistent with the audit specialization model based on the sales revenue of auditor clients.

Table 5, panel C, presents the regression model results for AUS_F, where audit specialization is based on audit fees. We find that the AUS_F*TPMIS coefficient is positively and significantly associated with AUTB_PUTB, UTB_TA, and UTB_LN (p < .10 or better), and significantly and negatively associated with AUTB > PUTB (p < .01), furnishing additional (but inconsistent) support for H2 based on the audit fee measure. For the AUS_F*THAV coefficient, we observe that it is significantly and negatively associated with AUTB > PUTB (p < .05). Finally, the AUS_F*FTRD coefficient is significantly and positively associated with AUTB > PUTB and UTB_LN (p < .10 or better), furnishing some additional (consistent) support for H2.

Taken together, the evidence presented in Table 5, panels A–C, generally shows that specialist auditors magnify the association between transfer pricing aggressiveness and foreign tax rate differentials, and UTB estimates. A possible reason for these findings is that specialist auditors may assist firms to achieve economies of scale and efficiencies in terms of international tax planning that come as a direct result of being an industry specialist, and perhaps also through audit spillover effects. In fact, specialist auditors may help a firm to galvanize its international operations to increase the order of magnitude of tax benefits that will inevitably have associated uncertainties. Nevertheless, we report inconsistent results concerning the impact of specialist auditors on the association between tax haven use and UTB estimates.

6.5 Additional analysis: the impact of uncertain tax position reporting requirements on the association between income-shifting arrangements and unrecognized tax benefits

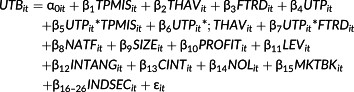

(7)

(7)Table 6 presents the regression results for the additional analysis. We find that the UTP coefficient is significantly positively associated with AUTB > PUTB (p < .05), indicating that the post 2010 UTP reporting requirements represent an important driver of the difference between actual and predicted UTBs. For the UTP*TPMIS coefficient, we find that it is positively and significantly associated with AUTB_PUTB, AUTB > PUTB, UTB_TA, and UTB_LN (p < .10 or better). The results indicate that transfer pricing aggressiveness is a significant driver of UTBs in the post-UTP implementation period. Significant and positive associations are also found between THAV*UTP and AUTB_PUTB, and AUTB > PUTB, reflecting the fact that tax haven use is also a driver of UTBs in the post-UTP implementation period. However, no significant results are found for the UTP*FTRD coefficient.

| Variables | Predicted sign | AUTB_PUTB(OLS) | AUTB > PUTB(LOGIT) | UTB_LN(OLS) | UTB_TA(OLS) |

| TPMIS | + | −0.0584 | −0.3347 | −0.3055 | 0.0007 |

| (−0.23) | (−0.84) | (−0.71) | (0.23) | ||

| THAV | + | 0.4186 | 0.2996 | 0.5805 | 0.0047 |

| (2.14)** | (0.94) | (1.97)** | (3.15)*** | ||

| FTRD | + | 0.1050 | 0.0424 | 0.0777 | 0.0013 |

| (2.50)** | (0.49) | (1.68)* | (3.18)*** | ||

| UTP | ? | 0.0720 | 1.3061 | 0.1723 | 0.0002 |

| (0.28) | (2.31)** | (0.63) | (0.08) | ||

| UTP*TPMIS | ? | 0.7381 | 1.9429 | 1.0981 | 0.0056 |

| (2.87)*** | (2.52)** | (2.63)*** | (1.94)* | ||

| UTP*THAV | ? | 0.3106 | 0.9152 | 0.2283 | −0.0004 |

| (1.76)* | (2.78)*** | (0.90) | (−0.33) | ||

| UTP*FTRD | ? | −0.0316 | 0.0197 | 0.0465 | −0.0002 |

| (−0.83) | (0.24) | (1.05) | (−0.60) | ||

| NATF | + | 0.0250 | 0.0261 | 0.0240 | 0.0002 |

| (1.88)** | (1.17) | (1.57)* | (1.58)* | ||

| SIZE | + | 1.0127 | −0.2268 | 0.7932 | −0.0001 |

| (7.62)*** | (−1.03) | (5.33)*** | (−0.11) | ||

| PROFIT | + | −0.0486 | −0.0999 | 0.0076 | −0.0004 |

| (−0.87) | (−0.67) | (0.09) | (−0.59) | ||

| LEV | + | 0.0162 | 0.6131 | 0.2718 | −0.0060 |

| (0.04) | (0.90) | (0.53) | (−1.64)* | ||

| INTANG | + | −0.4341 | −0.0884 | 0.0115 | 0.0004 |

| (−1.34)* | (−0.16) | (0.03) | (0.11) | ||

| CINT | + | −0.0630 | 0.2964 | −0.0463 | −0.0002 |

| (−0.50) | (1.54)* | (−0.36) | (−0.13) | ||

| NOL | + | −0.0234 | 0.3097 | 0.0690 | 0.0009 |

| (−0.14) | (0.79) | (0.26) | (0.62) | ||

| MKTBK | + | −0.0002 | 0.0014 | −0.0004 | −0.0000 |

| (−0.55) | (0.95) | (−0.71) | (−0.04) | ||

| Constant | ? | −6.1285 | −1.2924 | −5.2757 | −0.0009 |

| (−13.17)*** | (−1.43) | (−7.95)*** | (−0.21) | ||

| INDSEC | ? | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| YEAR | ? | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Adj. R2 | 0.669 | 0.167 | 0.525 | 0.182 | |

| N | 2097 | 2097 | 2097 | 2097 |

- *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the .10, .05, and .01 levels respectively. The p-values are one-tailed for directional hypotheses and two-tailed otherwise, and are calculated based on standard errors that are clustered at the firm-level (Petersen, 2009).

- OLS, ordinary least squares.

- Variable definitions: UTP = a dummy variable, coded as 1 for the 2010–2016 years, otherwise 0 (2007–2009 years), and all other variables are defined in Table 2.

Overall, these set of regression results show that the UTP reporting requirements magnify the positive association between transfer pricing aggressiveness and tax haven use, and UTBs in the post-UTP implementation period.

7 CONCLUSION

This study explores the association between income-shifting arrangements (i.e., transfer pricing aggressiveness, tax haven use, and foreign tax rate differentials) and UTBs, as well as analyzing the impact of audit specialization on the association between income-shifting arrangements and UTBs. We find that income-shifting arrangements characterized by transfer pricing aggressiveness, tax haven use, and foreign tax rate differentials are significantly positively associated with UTBs. We also find that audit specialization magnifies the positive association between transfer pricing aggressiveness and UTBs, and foreign tax rate differentials and UTBs. Finally, in additional analysis, we provide some evidence showing that the positive association between income-shifting arrangements and UTBs is magnified in the post-2010 UTP reporting requirement period.

Our study makes some noteworthy contributions. First, it shows that audit specialization magnifies the positive association between transfer pricing aggressiveness and UTBs, and foreign tax rate differentials and UTBs. To the best of our knowledge, no prior study has considered the linkages between audit characteristics such as audit specialization, income-shifting arrangements, and UTB estimates. Second, in additional analysis, we also provide some new evidence indicating that the positive association between income-shifting arrangements and UTBs is magnified in the post-2010 UTP reporting requirement period. Third, this study is also timely because there are a number of audit implications stemming from large or abnormal UTB estimates and reporting requirements. For example, the link between financial reporting and tax reporting of UTBs post implementation of the UTP reporting requirement from 2010 has placed more pressure on auditors in terms of identifying and evaluating potential tax uncertainties (Robinson & Schmidt, 2013). Finally, the findings of this study should be of interest to auditors, policymakers, regulators, and tax authorities (e.g., the IRS).

ENDNOTES

- 1 FIN48 Accounting for Uncertainty in Income Taxes, effective for the fiscal years beginning after December 15, 2006, is classified as Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) 740–10-25 under the Financial Accounting Standards Board's (FASB's) new codification for US generally accepted accounting principles. FIN48 was introduced by the FASB to provide financial statement users with information about the uncertainties a firm faces in computing its tax liability estimates (FASB, 2006). FIN48 mandates the recognition, measurement and disclosure of UTBs detailed in a firm's tax return and financial statements. That part of the tax benefit that does not meet the general recognition criterion which reflects anticipated future disallowed tax benefits is then recorded as a liability or UTB in a firm's financial statement tax footnotes (FASB, 2006). The UTB estimate is also commonly referred to as a “tax reserve” or “contingent liability” in the extant literature (Hanlon & Heitzman, 2010).

- 2 We define corporate tax aggressiveness in our study as any transaction or event that leads to a reduction in the amount of corporate taxes paid by a firm through targeted strategies and arrangements (e.g., Hanlon & Heitzman, 2010). Hanlon and Heitzman (2010) view tax aggressiveness as falling toward one end of the spectrum of tax avoidance strategies where there is concerted effort by a firm to significantly reduce the amount of its corporate taxes payable.

- 3 It may take many years for a firm to be selected for tax audit following lodgement of its tax return. Further, after an audit examination is completed, a firm may take many years to appeal or litigate the IRS's findings.

- 4 For instance, Cazier et al. (2015) shows that UTB estimates are adjusted to achieve earnings targets.

- 5 The CAP program is a mutual audit and risk assessment process between a firm and the IRS that identifies and resolves material tax issues before a firm lodges its tax return (Beck & Lisowsky, 2014).

- 6 This assertion is supported by research by Gleason and Mills (2011), who find that a firm records adequate levels of UTB estimates when its auditor also provides tax services consistent with information spillover effects, and Ciconte et al. (2016), who observe that auditor-provided specialist tax services improve the informativeness of a firm's UTB estimates regarding future cash flows.

- 7 Strict adherence to the arm's-length principle in the pricing of goods and services for a firm is problematic in practice because there may not be an active market to compare prices outside of a firm, particularly for intangible assets (Bartelsman & Beetsma, 2003).

- 8 Refer to Treasury Regulation Section 1.6662–6.

- 9 For instance, management may have to consider many factors, ranging from economic and financing inputs in the calculation of arm's-length transfer prices, the choice of transfer pricing methodology, profit analysis, and probability estimates to determine the amount of a firm's tax benefit that is likely to be sustained under IRS audit examination.

- 10 Drucker (2011) claims that some of the largest tax audits currently being undertaken or recently completed by the IRS in the USA involve aggressive transfer-pricing transactions to low-tax jurisdictions such as tax havens.

- 11 For example, auditors with specialized economic, tax, and legal expertise may assist firms in effectively reducing global tax liabilities via income-shifting arrangements, leading the firm to record large UTB estimates.

- 12 Specifically, benefits of auditor-provided industry experts include economies of scale, production efficiencies, higher quality audits and disclosure advice (Donohoe & Knechel, 2014).

- 13 For instance, audit firms may accrue skills and knowledge in terms of tax-effective ways in which to shift income between group members for pharmaceutical firms or high-technology firms.

- 14 We focus our attention on the top firms by market capitalization because of the requirement to hand collect data relating to several of our main variables of interest (see later).

- 15 This particular period was chosen to commence with the effective date of implementation of FIN48 (fiscal years beginning after December 15, 2006) and the disclosure of UTB estimates in annual reports.

- 16 We note that Rego and Wilson (2012) obtain their P_UTB estimates using firms in the S&P 500 from which our sample is also drawn.

- 17 Lisowsky et al. (2013) note that there are data reliability issues with UTB estimates obtained from Compustat, so we hand collect actual UTB data from a firm's financial statements to resolve this issue.

- 18 An example of how UTBs are calculated pursuant to FIN48 is provided in Appendix A.

- 19 Some examples of the mispricing of goods and services for firms in our sample are shown in Appendix B.

- 20 Where a firm is involved in a tax audit with the IRS (or other tax authority) regarding transfer pricing aggressiveness under the US tax code and supporting regulations, it is required to disclose this information in its annual report as per US Accounting Standard ASC 450 Contingencies or International Accounting standard IAS37 Provisions, Contingent Liabilities and Contingent Assets. FIN48 disclosure requirements also ensure that transfer pricing audits are disclosed by a firm in its annual report. Paragraph 21(d) of FIN48 requires a firm to disclose information about whether the total amounts of its UTBs will significantly increase or decrease within the next 12 months of reporting date including the nature of the uncertainty and the nature of the event that could occur in the next 12 months that would cause the change (FASB, 2006). Paragraph 21(e) of FIN48 also requires disclosure of a description of the tax years that remain subject to audit examination by a major tax jurisdiction (FASB, 2006).

- 21 We obtain data on adjustments to income tax expense on pre-tax accounting profit as a result of foreign tax rate differentials from the accounting income-to-taxable income reconciliation statements contained in the tax footnotes of a firm's annual report.

- 22 Adjustments to income tax expense on accounting profit are provided in the accounting income-to-taxable income reconciliation statement in the notes to the financial accounts in the annual report.

- 23 Audit industry specialists are those who possess particular skills or experience in relation to certain industry operational, accounting, tax, or financing practices that enable them to provide higher quality audits or more efficient services to clients in that industry (Audousset-Coulier et al., 2016).

- 24 In fact, we use this approach instead of the market share approach because, as indicated by Audousset-Coulier et al. (2016), the portfolio approach gives more consideration to the relative distribution of audit services and audit fees across industries served by each audit firm.

- 25 We note that these three audit specialization models have all been successfully applied in prior research (e.g., Chi & Chin, 2011; Craswell, Francis, & Taylor, 1995; Hogan & Jeter, 1999).

- 26 For brevity, we note that we do not report the subscript denoting a specific year.

- 27 Given that the status of a specialist auditor is latent, we follow prior research and use proxy measures of industry specialization. These measures are mostly derived from market share based on the assumption that industry expertise is built by repetition in similar settings, so a large volume of business in an industry denotes expertise. However, prior research also finds that market share has several limitations as a measure of specialization (e.g., Gramling & Stone, 2001; Krishnan, 2003), so we also use another proxy to address these shortcomings. In particular, we employ a widely used proxy for audit industry specialist as measured by audit fees in Equation 4. As per Neal and Riley (2004) and Audousset-Coulier et al. (2016), the appropriate cut-off point for market share is given by (1/N) × 1.2.

- 28 We specifically rely on a broad industry classification based on the approach adopted by Audousset-Coulier et al. (2016) to mitigate the risk that our results could be affected by industry classification.

APPENDIX A.: EXAMPLES OF THE CALCULATION OF UNRECOGNIZED TAX BENEFITS

The evaluation of a tax position as per FIN48 is a two-step process (FASB, 2006). The first step is recognition. An enterprise determines whether it is more likely than not that a tax position will be sustained upon examination, including resolution of any related appeals or litigation based on the technical merits of the position. The second step is measurement of a tax position. A tax position that meets the more likely than not recognition threshold is measured to ascertain the amount of the benefit to recognize in the financial statements. The tax position is measured as the largest amount of tax benefit that is greater than 50% likely of being realized upon ultimate settlement.

The following is an example of recognition and measurement of UTBs derived using examples provided by FASB (2006). Assume a firm anticipates claiming a tax credit of $1,000,000 relating to R&D expenditure. Upon review of the supporting documentation, management believes it is more likely than not that the firm will ultimately sustain a tax benefit (i.e., a tax deduction) of $650,000 that can be recognized in the financial statements as tax assets or tax liabilities. Because it is uncertain that the additional tax benefit of $350,000 recorded on the tax return will be allowed by the IRS as that amount does not meet the more likely than not threshold, it is not recognized in the financial statements and instead is recorded as a liability or unrecognized tax benefit, even though the full tax benefit of $1,000,000 is recorded in that firm's tax return. In this example, management has 65% confidence in the technical merits of the tax position based on tax law, legal intent, and precedent cases. Thus, $650,000 of the overall tax benefit of $1,000,000 meets the recognition criterion. The firm has considered the amounts and probabilities of the possible estimated outcomes as follows:

| Possible estimated outcome ($) | Probability (%) | |

| Individual | Cumulative | |

| 1,000,000 | 5 | 5 |

| 800,000 | 25 | 30 |

| 650,000 | 25 | 55 |

| 500,000 | 20 | 75 |

| 350,000 | 10 | 85 |

| 100,000 | 10 | 95 |

| 0 | 5 | 100 |

- As $650,000 is the largest amount of benefit that is greater than 50% likely of being realized upon examination and settlement by the IRS, the firm would recognize a tax benefit of $650,000 in the financial statements and a liability or unrecognized tax benefit of $350,000 to be disclosed in the financial statements. The measurement of the tax position is based on management's best judgment of the amount the firm would ultimately accept in a settlement with taxing authorities.

- In a separate scenario, a firm has incurred expenditures of $1,000,000 on salaries to employees that are not subject to any limitations on deductions in a given year. Management concludes that the salaries are fully deductible based on clear and unambiguous tax law. Management has a high confidence (100%) level in the technical merits of that tax position and is confident that the full amount of the deduction will be allowed and that it is greater than 50% likely that the full amount of the tax benefit of $1,000,000 will be ultimately realized. There is no UTB in this scenario.

APPENDIX B.: EXAMPLES OF MEASURES TO RECORD TRANSFER PRICING AGGRESSIVENESS

Non-commercial pricing of related party transactions