‘It was a big monetary cut’—A qualitative study on financial toxicity analysing patients’ experiences with cancer costs in Germany

Funding information

This work was supported by the German Cancer Aid (grant number 70112452).

Abstract

Receiving information about expected costs promptly after a cancer diagnosis through psycho-oncology care or social counselling is crucial for patients to be prepared for the financial impact. Nevertheless, less is known about financial impacts for cancer patients in countries with statutory health insurance. This study aims to explore the full scope of costs that constitute the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis in Germany and to identify the reasons for high financial decline. Semistructured interviews with 39 cancer patients were conducted between May 2017 and April 2018. Narratives were analysed via qualitative content analysis. Several factors influenced cancer patients’ indirect costs and direct medical and non-medical costs. For many patients, these changes resulted in higher indirect costs caused by income losses, especially when surcharges for shift work, travel expenses or company benefits ceased and were not reimbursed. Higher direct medical costs were caused by co-payments and additional non-refundable costs. Non-medical costs were reported to increase for some patients and to decrease for others, as for example, leisure activity costs either increasing because of pampering oneself to cope with the diagnosis and undergoing therapy or decreasing because of not being able to participate in leisure activities during therapy. When analysing the financial impacts of individuals' total costs, we found that some patients experienced no financial decline or an overall financial increase. Most patients experienced overall higher costs, and income loss was the main driver of a high financial decline. Nevertheless, decreased non-medical costs due to lower work-related and leisure activity costs could compensate for these higher costs. Cancer patients are confronted with a variety of changes in their financial situations, even in countries with statutory health insurance. Screening for cancer patients with a high risk of financial decline should consider any effects on indirect costs and direct medical and nonmedical costs.

What is known about this topic?

- Cancer patients are confronted with a variety of costs that lead to short- and long-term financial impacts.

- Financial decline can be brought about by indirect, direct medical and direct nonmedical costs.

- A lack of knowledge of expected costs can increase subjective financial stress.

What this paper adds?

- Even in countries with statutory health insurance cancer patients are confronted with a variety of costs.

- Income loss was the main driver of a high long-term or short-term financial decline.

- Some patients experienced no financial decline or an overall financial increase due to decreased non-medical costs (e.g. work-related or leisure activities), which compensated for higher indirect and direct medical costs.

1 INTRODUCTION

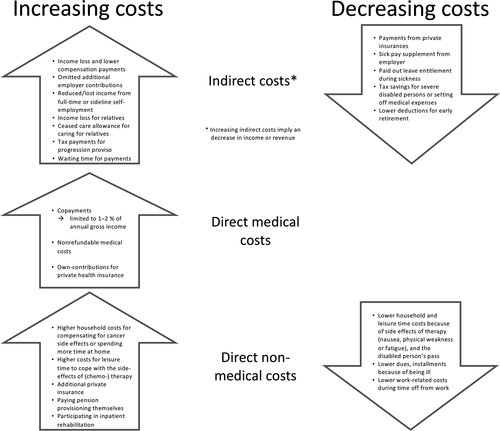

Due to continuing improvements in cancer treatment, the number of cancer survivors is growing (Miller et al., 2016). While a positive development, this shift implies that an increasing number of patients are confronted with various (long-term) consequences. One major problem is the prevalence of financial toxicity following a cancer diagnosis, which ranges between 15% and 79% of patients who experience financial burden depending on the underlying measurement and country (Azzani, Roslani, & Su, 2015). Financial toxicity is defined as the objective financial burden and subjective financial distress experienced by patients (Carrera, Kantarjian, & Blinder, 2018). The objective financial burden refers to costs in relation to wealth and income. These costs are mainly classified as indirect costs, direct medical costs and direct non-medical costs (Altice, Banegas, Tucker-Seeley, & Yabroff, 2017; Azzani et al., 2015; McNulty & Khera, 2015).

Direct medical costs for hospitalisation and physician visits and increasing costs for cancer drugs have been found to have the strongest impact on financial toxicity in countries without universal health coverage (Carrera et al., 2018; Pisu, Henrikson, Banegas, & Yabroff, 2018; Zafar et al., 2013). The underlying reason for indirect costs is productivity loss, which results in lower income (Altice et al., 2017; Pearce et al., 2018). More than 30% of cancer patients do not return to work after receiving a cancer diagnosis (Mehnert, 2011). Applied measures of income loss are unemployment, decline in hours worked, decreased annual labour-market earnings and decreased total family income. (Zajacova, Dowd, Schoeni, & Wallace, 2015). In Denmark, a country with welfare system and high public income transfer, the negative effect of cancer on personal income is very small (Andersen, Kolodziejczyk, Thielen, Heinesen, & Diderichsen, 2015).

The reasons for direct non-medical costs have been found to include costs generated from travel and parking, increased household bills, new clothing, healthier food, household- and childcare-related services, fitness classes, relocation, house modifications and family and friends (Amir, Wilson, Hennings, & Young, 2012; Céilleachair et al., 2012; Longo, Fitch, Grignon, & McAndrew, 2016; McGrath, 2016b; Moffatt, Noble, & Exley, 2010; Timmons, Gooberman-Hill, & Sharp, 2013b). Knowledge of the expected costs is crucial for cancer patients to reduce their financial distress (Peppercorn, 2014) because experiencing a higher than expected financial burden has been found to increase experiences of financial distress (Chino et al., 2017). Furthermore, a study analysing the viewpoints of oncology navigators found that they were aware of the high financial burden of their patients but had insufficient knowledge to address this issue (Spencer et al., 2018). Nevertheless, the financial impact seems to differ between countries depending on the healthcare and welfare system, for example, higher medical care costs in countries with limited publicly funded healthcare. Thus far, information on the indirect costs and direct medical and non-medical costs for cancer patients in countries with statutory health insurance is lacking.

The German healthcare system is a multipayer healthcare system with a combination of compulsory statutory and private insurance. Approximately 90% of the population is covered by statutory health insurance, which is part of the social security system and is characterised by the solidarity principle. Most costs for inpatient and outpatient healthcare, medication, transport and medical aids are covered by statutory health insurance with only low co-payments. The out-of-pocket costs for co-payments are capped at 2% (1% after 1 year of being chronically ill, such as cancer or diabetes) of the gross annual household income upon request. Some costs, such as non-prescription medication, individual health services and transportation to outpatient care, either must be applied for or are generally not covered. In addition, income loss is typically mitigated by sickness benefits, which cover approximately 70% of an individual's regularly relevant total gross income for up to 78 weeks. Furthermore, the social security system (e.g. pension insurance, unemployment insurance) protects against most income loss, for example, from unemployment or reductions in earning capacity. Further explanations of social welfare benefits in Germany are given in Appendix S1. Due to the comprehensive social security systems in countries with statutory health insurance, financial toxicity should be of little concern in these countries. Nevertheless, a recent study in Germany found that 15 months after diagnosis, cancer patients were confronted with average 3-month-out-of-pocket medical costs (not including medication) of €148 (Büttner et al., 2019). However, less is known about the additional medication costs and the total family income decline as well as the non-medical costs for cancer patients in Germany.

In addition to a deeper understanding of the costs that induce financial toxicity, identifying high-risk patients is important (Carrera et al., 2018). Medical and non-medical out-of-pocket costs have been found to be higher for patients with, for example, younger age, higher household income and longer distance from treatment centres (Baili et al., 2016; Davidoff et al., 2013; Newton et al., 2018; Pisu, Azuero, Benz, McNees, & Meneses, 2017; Valtorta & Hanratty, 2013). Furthermore, studies have found that low socioeconomic status is a risk factor for unemployment after a cancer diagnosis; for women, a cancer diagnosis results in a higher risk of unemployment, but mainly male cancer patients seem to be affected by a total decline in family income (Torp, Nielsen, Fosså, Gudbergsson, & Dahl, 2013; Zajacova et al., 2015). To our knowledge, only one study has considered the combined effect of direct medical costs, non-medical costs and indirect costs and found that predictors of greater total costs for breast cancer patients were higher household income and longer time since diagnosis (Arozullah et al., 2004). However, as past studies have predominantly been cross-sectional quantitative studies, they mainly identified factors associated with predefined medical and non-medical costs, while other sources of financial impacts, such as indirect costs, and the underlying reasons for a substantial loss of material resources remain unclear (Gordon, Merollini, Lowe, & Chan, 2017). Screening tools for patient costs are underdeveloped and need to be highly individually adapted to the healthcare system and individual patients (Liang & Huh, 2018). Examining patients’ particular circumstances, experiences and viewpoints can help in developing a better understanding of the reasons for the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis (McGrath, 2016a; Timmons, Gooberman-Hill, & Sharp, 2013a). Nevertheless, qualitative studies that analyse costs and explore when and how higher costs lead to high financial decline are lacking—particularly in countries with statutory insurance systems.

Overall, we conclude the following: first, information about the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis in countries with statutory health insurance and social security systems—to enable the provision of information to cancer patients in a timely manner—is lacking but needed, as the financial consequences differ depending on the system; second—independent of the healthcare system—less is known about how all costs operate together to influence the individual patient and result in high or low financial decline. The objective of this study was to examine the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis and the sources of spending of cancer patients in a country with statutory health insurance. Therefore, this analysis aims to (a) explore the full scope of costs after a cancer diagnosis in Germany and (b) identify the reasons for high financial decline based on a consideration of all costs together.

2 METHODS

2.1 Design and sampling

We conducted an exploratory qualitative study of cancer survivors in Germany to capture the essential aspects of individuals’ experiences with the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis. The Ethics Review Committee of the Medical Faculty at the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg approved the study (No. 2016-126). The study participants were selected based on the following criteria: had received a diagnosis of a first breast, prostate, lung or colorectal cancer; was aged ≥30 years; and had completed acute treatment for cancer within the last 5 years. For the purpose of contrasting, we aimed to sample information-rich participants to reach maximum variation in experiences with financial toxicity. Characteristics such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, family status and the extent of the financial impact and the following subjective financial burden were considered when sampling to achieve maximum variation. To increase the variation of the sample, we broadened the inclusion criteria throughout the process of sampling and analysis, and we included some patients with other cancer entities, with recurrence, with a second cancer diagnosis or who were still receiving long-term acute therapy, as these patients had important experiences with their financial situation, which helped reach theoretical saturation regarding financial toxicity. We recruited cancer patients in Halle (Saale), Germany; we contacted potential participants in diverse ways in hospitals, clinical outpatient departments or resident specialists, where patients were informed about the study mainly by nurses, and through flyers, for example, in an advisory office for cancer patients. In total, 58 participants gave their consent to be contacted by a member of the research team, or they contacted the study group by themselves. To make conscious decisions about who would be included in the study, the research team asked each contact person or patient to give a brief overview of the patient's sociodemographic background, medical history and/or subjective rating of the extent of financial impact and psychosocial burden. Most patients provided this information by themselves. At the beginning of the sampling process, we included every patient. Later in the analysis and sampling process, we selected only patients who provided maximum contrast with the previous recruited patients to confirm or contradict the present findings until saturation was reached with regard to an overall understanding of financial toxicity in Germany. This resulted in a sample of 39 information-rich participants for the study.

2.2 Data collection

A semistructured interview schedule (Appendix S2) was used to guide the interview process, increase consistency and facilitate the subsequent data analysis. The interview schedule was developed with the help of the existing literature and the experiences of experts working in social counselling for cancer patients. One major question focused on the participants’ financial situations and how they changed after their cancer diagnoses. Following the interviews, the participants’ basic sociodemographic data were obtained with a short, standardised questionnaire, and the interviewer subsequently wrote a field note for each interview. The in-depth interviews were conducted between May 2017 and April 2018. All participants were contacted and informed in advance about the study, and the interviews were conducted only after the participants gave written informed consent. Based on each participant's preference, the interviews took place at the Institute of Medical Sociology (IMS), at the participant's home or in the outpatient clinic during aftercare appointments. Two female employees of the IMS conducted the interviews face to face after introducing themselves as research associates. Both have years of experience in qualitative health research and an education background in economics or sociology. All interviews were conducted and analysed in German. For the quotations and interview guide presented in this manuscript, we conducted a double-blind, two-way translation from German to English to German that was checked by a third person. The interviews mainly included only the participant and one interviewer; however, for seven of the interviews, family members were present at the participant's request. The interviews lasted between 23 and 160 min (depending on the extent of financial impact and financial distress), with an average length of 68 min. All but one of the interviews were audiotaped with the interviewee's permission. The second to last interview was not recorded on the participant's request, but as the coding tree was highly developed at this time, the notes made during the interview provided a solid basis to subsequently code the participant's experiences.

2.3 Data analysis

The transcripts were analysed step by step concurrently with the recruitment of participants and the conduct of the interviews via qualitative content analysis, which is appropriate for predominantly descriptive research questions (Schreier, 2012). Initially, six transcripts were double coded with a data-driven (inductive) approach by trained coders from the qualitative working group at the IMS. These codes were used to develop an initial code structure with categories. Subsequently, four interviews were double coded by SLL and NS to enhance the preliminary coding tree. The remaining transcripts were coded by either SLL or NS, and discrepancies were resolved through discussions. MAXQDA 12.0 software was used to facilitate the coding and analysis. Overall, each cost driver was extracted from the codes for every cost category and participant. The specific amounts of the costs were clearly remembered by some patients, but the majority of the patients provided approximate information about the amounts or gave an overall conclusion of the overall financial impact and/or changes in costs for the three cost categories. In some cases, the costs needed to be estimated based on the narratives. From all the direct and indirect information given throughout the interviews, we estimated the financial changes for every patient and for every cost category as best as possible and summed them. Afterwards, we compared the amounts of overall financial decline and identified the cut-off point to define high financial decline as follows: costs >€10,000 in the first year after diagnosis (approximately 33% of the average net annual household income in this region of Germany) or a report of being confronted with (subjectively assessed) substantial long-term costs of approximately more than €3,000 per year for several years. Finally, we compared and contrasted the narratives of patients with or without high financial decline.

3 FINDINGS

The 39 participants were aged between 40 and 86 years (Table 1). All of them described the consequences of their cancer diagnoses for their financial situations in detail. In the present analysis, we report the participants’ experiences with changes in costs resulting from their cancer diagnoses and treatment. In the following section, we describe the factors that increased and decreased the patients’ indirect costs and direct medical and non-medical costs and how social welfare legislation has influenced these cost categories (Figure 1). For a better understanding of the results, relevant social welfare benefits in Germany are explained in detail in Appendix S1. Accordingly, we describe the factors characterising high individual overall financial decline.

| Characteristic | Description | Number of participants |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Average age (range) | 59 years (40–86) |

| Gender | Female | 18 |

| Male | 21 | |

| Cancer diagnosisa, b | Breast | 11 |

| Colon | 9 | |

| Lung | 7 | |

| Prostate | 7 | |

| Other | 5 | |

| Year of cancer diagnosisa, c | 2003–2012 | 7 |

| 2013 | 2 | |

| 2014 | 3 | |

| 2015 | 10 | |

| 2016 | 14 | |

| 2017 | 3 | |

| Employment status at cancer diagnosisa, c | Working | 23 |

| Self-employed | 5 | |

| Pensioner (retired, disability) | 8 | |

| Unemployed (compensation, basic income) | 3 | |

| Health insurancec | Statutory | 36 |

| Private | 3 | |

| Household and dependents | Partner, parents, older children | 21 |

| Single | 10 | |

| Families (living with children) | 6 | |

| Single parent | 2 |

- a With the aim of achieving maximum variation, we included patients with a cancer diagnosis other than breast, prostate, lung or colon cancer and patients with a second cancer diagnosis or recurrence whose first diagnosis was made more than 5 years ago.

- b Related to the last cancer entity.

- c At the time of the first cancer diagnosis.

3.1 Indirect costs

Many participants experienced increased indirect costs due to a decrease in net income. When reporting the reasons for changes, the participants named several causes that increased and decreased their indirect costs (Figure 1). First and foremost, income losses from not working increased their indirect costs. For those with statutory health insurance this income loss during sick leave was mitigated by partial compensation from sickness benefits or temporary payments from statutory pension insurance. Other wage compensation for those who were unable to work included welfare benefits such as unemployment benefits, basic income, the reduced-earning-capacity pension, and early retirement.

Because most of the money we earn comes from our surcharges. Night surcharges, so all the Sunday bonuses, public holiday surcharges. Thus, we earn megabucks, of course. Megabucks are relative. It could be more for everyone. Anyway, this is automatically missing. That does not count anywhere. (B25, female, 55 years)

Well, my wife worked in the company as well. […] Well. Until I got sick, that is to say. Then, she practically went into early retirement with deduction. There was no other way. (B27, male, 70 years)

[…] because I was penalized [at the employment office], and everybody was stubborn until they said, ‘This woman is off sick. She does not have just cough or a cold. We will pay her the money now’.’ But nothing happened for a long time. At this time, I did not even receive any sickness benefits. (B17, female, 40 years)

I have always thought that this is a motivation for me, that you get holidays if you go to work. But I was on sick leave, so normally I have no claim for holidays. And I found out afterwards that I received the money for two years of leave entitlements. (P1, male, 53 years)

3.2 Direct medical costs

Direct medical costs increased following cancer diagnosis and treatment for several reasons (Figure 1). Those with private insurance reported that their direct medical costs were covered by health insurance, but in some cases, they had to make their own contributions. Most of the participants had statutory health insurance and differentiated between co-payments for costs, which were covered by health insurance, and additional non-refundable costs, which were not covered.

You get a prescription from the doctor, then go down to the pharmacy. And then, I remember, I looked like a cow when it thunders. I had €10 with me because I was going to chemotherapy, not to shop. And then they charged me €70 in the pharmacy. (B4, female, 48 years)

But I had to pay three hundred euros myself for my wig to have a good one. (B9, female, 49 years)

In addition to this, due to the treatment and everything, I needed ointments and bandages. And that does not count as/, well, no health insurance pays this. These are remedies that you have to pay for yourself. (B25, female, 55 years)

3.3 Direct non-medical costs

Well, sure. Of course. Electricity. Electricity, heating. You are at home the whole day. The problem is it’s almost 50% more. Because when I am off at work, I turn down the heating. Then, the electricity is also less because you watch TV or listen to the radio or whatever to a lesser extent. Thus, the costs rise enormously. ENORMOUSLY. These are the little things no one is aware of. (B18, male, 52 years)

The drive to work, yes, and I do not know, there was just more [money] left over. […] I have to say, that you maybe had more expenses when you were at work because you have to/did not always want to have just a sandwich from the lunch box, but instead a sausage, a steak or something. Now, it depends on the phases, as I said, how you are doing. Then you make a meal on your own, and this can be done cheaply. (B34, male, 56 years)

3.4 Reasons for experiencing high financial decline

When analysing the financial impact of the cancer diagnosis for each individual while considering all costs together, we found that some patients experienced an overall slight decrease in income or nearly no changes in their financial situations. Therefore, the majority of patients experienced short-term financial decline amounting to less than € 10,000. These patients experienced, for example, no change in their income or an income decline that was mitigated by a decline in non-medical costs, especially for leisure activity costs or work-related costs. In comparison, some participants reported a high financial decline. These patients experienced considerable decreases in income with no compensating decline in non-medical costs. In contrast to participants with smaller financial impacts, those who experienced a large short-term decline in income had (1a) comparatively low proportional sickness benefits because of high surcharges not covered by sickness benefits or (1b) reductions in self-employment work (which could also involve other family members) without private coverage.

Some patients reported being confronted with substantial long-term costs due to long-term income loss, which was caused by (2a) working before diagnosis and not returning to work (because of being a manual worker or freelancer, experiencing a recurrence, or having a higher severity cancer or long-term side effects) but receiving a reduced-earning-capacity pension with no additional work on the side or (2b) having repeatedly affected or precarious income because of the recurrence of cancer or a new cancer diagnosis or because of losing their jobs or no longer receiving care allowances for dependents.

4 DISCUSSION

In analysing the reasons underlying the indirect costs and direct medical and non-medical costs experienced by cancer patients in Germany, we found that cancer impacts patients’ costs even in countries with universal healthcare systems. However, the financial impact in Germany seems to be less severe and to have different underlying causes than that in other countries due to lower costs. Different factors increase or decrease these costs and result in higher indirect costs and medical costs for many patients. In this study, whereas total non-medical costs increased for some patients, they decreased for others. When analysing all three cost categories with respect to the financial impact of cancer, we found income loss to be the main driver for high financial decline, but we also observed that decreased non-medical costs due to lower work-related costs and engagement in fewer leisure activities can compensate for these higher costs, resulting in only moderate financial impact for the patients.

In Germany, no studies have analysed the reasons for cancer costs or the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis among patients by taking into account all cost categories together, but our findings confirm the results from another study indicating that cancer can negatively affect the financial situations of cancer patients (Singer, Claus, et al., 2018). As observed in another study, we found that most cancer patients in Germany face increases in medical costs (Büttner et al., 2019). We also noted that income has a major impact on patients’ financial situations in Germany, which can be weakened by decreased non-medical costs. There is no evidence regarding the impact of cancer on indirect and non-medical costs in Germany, but 24% of cancer patients did not return to work during the year after rehabilitation and therefore experienced long-term income loss (Mehnert & Koch, 2013).

We found several reasons for decreases and increases in indirect and non-medical costs as well as reasons for increases in medical costs. A comparison with other international studies on the financial impact of cancer showed that the causes of costs and their categorisation are affected by the healthcare system. Therefore, the results differ from those reported by other studies. First, this study found that medical costs in Germany are regulated differently by private and statutory health insurance as well as within the statutory system, where they are divided into limited co-payments and additional non-covered costs. Second, indirect costs are mainly buffered by the social welfare system, but regulations, such excluding social security-free surcharges from the calculation of the sickness benefit, result in additional increases in costs for patients. Third, costs for transportation to chemotherapy are covered by statutory health insurance in Germany. Therefore, co-payments for transportation costs are defined as direct medical costs and other non-covered transportation costs are defined as non-medical costs, whereas other studies defined transportation costs mainly as non-medical costs (Baili et al., 2016; McGrath, 2016b). Last, we found diverse increasing and decreasing influences on non-medical costs in this study that were not affected by social welfare legislation but that have been rarely analysed in international studies. Some studies have described increased non-medical costs following cancer diagnosis due to the costs of heating, new clothing, healthier food and household-related services (Amir et al., 2012; Céilleachair et al., 2012; Longo et al., 2016; McGrath, 2016b; Moffatt et al., 2010; Timmons et al., 2013b). In addition, only one study described decreased non-medical costs related to household and leisure activities due to physical limitations (Amir et al., 2012). Moreover, we found that work-related expenses such as gas or a second home, and costs for dues and instalments decreased following diagnosis, which to our knowledge has not been described in the existing international research. Promptly receiving information regarding possible costs after diagnosis is crucial for patients to be prepared for financial impacts (Gordon, Walker, et al., 2017), because experiencing higher than expected financial burden has been found to increase financial distress (Chino et al., 2017). Social counselling is rarely used with cancer patients in Germany, and only 28% of participants address the topic of financial security in social counselling sessions (Ernst et al., 2016). However, psycho-oncology care and social counselling can be important, as it can help to substantially mitigate experiences of financial problems (Singer, Roick, et al., 2018).

We can confirm that income loss is a major cause of high short-term or long-term financial decline, as found in other studies (Arozullah et al., 2004; Bradley et al., 2007; Dean et al., 2019; Lauzier et al., 2013; Pearce et al., 2018). However, high medical costs, especially non-refundable costs, can increase the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis. Surprisingly, we found that the influence of non-medical costs can be the difference between high or low financial decline, as in some cases, decreases in non-medical costs were reported to compensate for (high) indirect and medical costs. Although some qualitative studies have analysed the factors driving costs in all three cost categories (Amir et al., 2012; Moffatt et al., 2010; Timmons et al., 2013b), to our knowledge, no quantitative study on the financial impact of cancer has considered decreased non-medical costs in its analysis. Even the recent frameworks for financial toxicity include primarily direct medical costs and related treatment costs in their definitions of objective financial burden. Although some reviews have also considered the indirect costs of income loss, they have not accounted for the phenomenon of decreased non-medical costs (Altice et al., 2017; Carrera et al., 2018; Gordon, Merollini, et al., 2017; McNulty & Khera, 2015). Therefore, it is not possible to directly compare our results with those of other studies on the risk factors for the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

We relied on patient memory, and the patients may not have remembered all the reasons for financial changes. Patients who did not feel subjectively stressed by their financial situations may not have given minor changes in costs much consideration when they occurred and therefore may not have reported these changes in the interviews. The strength of this study is that we did not conflate the financial impact with the coping mechanisms following financial decline or with subjective financial distress. Nevertheless, as we analysed the patients’ subjective views of financial impacts, our reporting, particularly on decreasing or increasing non-medical costs, might have been influenced by the subjective views of the participants regarding the objective financial burden they experienced and their perceived subjective financial distress. Importantly, when identifying risk groups, we analysed the participants’ descriptions of their overall financial impacts and not the costs relative to their income and assets. In addition, the estimated amounts of overall financial decline were determined only approximately and were therefore not presented. Nevertheless, the cut-off point of more or less than €10,000 to define high or low financial decline was very clear due to a greater gap. ‘High long-term costs’ were more difficult to define, as patients quantified long-term effects less precisely throughout the interviews. Therefore, the generated hypotheses on risk groups must be interpreted carefully and probably do not imply exclusivity. Although we conducted 39 interviews and reached saturation, the generalisability of the findings to all patients with cancer is limited. Within the broader context of the study, we did reach saturation regarding the framework of financial toxicity but not regarding all kinds of extra costs that patients might be confronted with. Furthermore, the generalisability of the findings to younger patients or families of children with cancer, patients with other (more expensive) cancer diagnoses or patients from other countries or regions is not known. Nevertheless, the importance of decreased or increased direct nonmedical costs for overall financial decline among cancer patients should be of international interest and has rarely been considered.

5 CONCLUSIONS

We found that patients are confronted with a variety of different costs and changes in their financial situations that are at least partly influenced by the healthcare system. The financial impact of a cancer diagnosis in Germany seemed to be less severe for most of the patients than that in other countries, and income was the main driver of experiences of high financial decline. Nevertheless, there were some unexpected costs caused by costs that are not covered or reimbursed in the social insurance system that cancer patients should be informed about promptly after diagnosis, such as those resulting from the regulation regarding co-payment exemptions, social security-free surcharges, non-refundable direct medical costs and self-employment indirect costs. In addition, healthcare policy should consider and address these costs. Furthermore, decreased non-medical costs (related to leisure activities or work) may prove to be important aspects in the analysis of financial toxicity, as they can compensate for increased costs. This might be relevant particularly for patients in countries with statutory health systems who have comparably low medical and indirect costs due to social welfare regulations and comparably high decreased work-related and leisure activity costs due to high costs prior to diagnosis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the patients who participated in this study and shared their experiences regarding this personal topic with us. For their assistance with recruiting patients for this study, we acknowledge the scientific assistants Julia Faltus and Johannes Niebuhr as well as the cooperation partners within the outpatient departments and doctors' practices, especially the nurses Karla Dieckmeyer, Sandra Radon and Stefanie Drosdziok. We thank Jürgen Walther and Marie Rösler from the German Cancer Society as well as Sven Weise from the cancer society of Saxony-Anhalt for the topical discussions and insights into the issue of financial toxicity from the viewpoint of social counselling. Finally, we thank the German Cancer Aid for financing the study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.