Social work-generated evidence in traumatic brain injury from 1975 to 2014: A systematic scoping review

Abstract

The International Network for Social Workers in Acquired Brain Injury (INSWABI) commissioned a systematic scoping review to ascertain the social work-generated evidence base on people with traumatic brain injury (TBI) of working age. The review aimed to identify the output, impact and quality of publications authored by social workers on this topic. Study quality was evaluated through assessment frameworks drawn from the United Kingdom National Service Framework for Long-Term Conditions. In the 40-year period from 1975 to 2014, 115 items were published that met the search criteria (intervention studies, n = 10; observational studies, n = 52; literature reviews, n = 6; expert opinion or policy analysis, n = 39; and others, n = 8). The publications could be grouped into five major fields of practice: families, social inclusion, military, inequalities and psychological adjustment. There was a significant increase in the number of publications over each decade. Impact was demonstrated in that the great majority of publications had been cited at least once (80.6%, 103/115). Articles published in rehabilitation journals were cited significantly more often than articles published in social work journals. A significant improvement in publication quality was observed across the four decades, with the majority of studies in the last decade rated as high quality.

What is known about this topic

- A seminal 1990 paper suggested that the biopsychosocial nature of traumatic brain injury (TBI) presented many opportunities for social work research.

- Previous reviews in the area have focused narrowly on specific fields of practice only (e.g. the impact of TBI on families).

- The trajectory of social work research output is unknown.

What this paper adds

- The first systematic, comprehensive overview of social work scholarship in TBI.

- By comparing the scholarly output over four discrete decades (1975–1984, 1985–1994, 1995–2004 and 2005–2014), the review demonstrates the increasing quantity and quality of the social work evidence base.

- Provides an important resource for evidence-informed practice and highlights avenues for future research.

1 INTRODUCTION

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a global public health issue. Studies have estimated a 5%–12% prevalence rate of TBI across developed countries (Anstey, Butterworth, Jorm, Christensen, Rodgers, & Windsor, 2004; Frost, Farrer, Primosch, & Hedges, 2012). In the United Kingdom alone, approximately 275 per 100,000 of the population sustain a TBI every year, with 25 per 100,000 incurring a severe grade of injury (Langfield, 2009). TBIs are most commonly caused by road accidents (car, motorbike, bicycle and pedestrian), falls, assaults and sporting injuries (Langfield, 2009; Mantell, 2010). In conflict zones, TBI usually result from gunshot, shrapnel wounds (Simpson & Tate, 2009) or, more recently, improvised explosive devices (Rona et al., 2012).

The impact of the TBI ripples out from the individual to their social networks and the wider community creating a broad array of social concerns (Mantell, 2010). These can include the breakdown of family relationships (Wood & Yurdakul, 1997), unemployment (Tyerman, 2012), social isolation (Rowlands, 2000), increased risk of homelessness (Oddy, Frances, Fortescue, & Chadwick, 2012), higher levels of incarceration (Williams, Mewse, Tonks, Mills, Burgess, & Cordan, 2010), depression (Tsaousides, Cantor, & Gordon, 2011) and elevated levels of suicide (Simpson & Tate, 2007). Underlying these problems, Daisley, Tams, and Kischka (2009) have categorised the disabilities arising from TBI as spanning physical and sensory impairment, cognitive impairment, communication problems, sexual issues, psychological adjustment and behavioural problems.

Social workers play multiple roles in the field of TBI (Carlton & Stephenson, 1990; Simpson, Simons, & McFadyen, 2002). These encompass the provision of client and/or family education; counselling or emotional support (Simpson et al., 2002); assistance in coping with hospitalisation; planning and support during the discharge and community re-integration process; help with guardianship/compensation issues including capacity assessment (Holloway & Fyson, 2015); tackling stigma and discrimination; facilitating social supports (Rowlands, 2000); advocating for/mobilising resources to help individuals and their families meet the long-term challenge of maintaining community participation (Degeneffe, 2001); and undertaking policy analysis/working for legislative change (Foster, Tilse, & Flemming, 2002).

In their 1990 review, Carlton and Stephenson observed that given the biopsychosocial impact of TBI, it was surprising that social workers had not published more on the subject. Twenty years later, the International Network for Social Workers in Acquired Brain Injury (INSWABI; see Simonson & Simpson, 2010; Simpson & Yuen, 2016) commissioned a systematic scoping review to identify the social work-generated evidence base in the field of TBI. Conducting the review reflects the growing recognition within the profession of the importance of research (Orme & Powell, 2008; Simpson & Lord, 2015a). This review provided the opportunity to determine the extent of the knowledge base within TBI that practitioners can draw upon, as well as ascertaining whether there is a growing research output (Brough, Wagner, & Farrell, 2013).

Previous studies have looked at the trajectory of social work research, encompassing a broad range of criteria (i.e. research output, staffing and funding). For example, Fisher and Marsh (2003) investigated social work output as a discipline over two rounds of the United Kingdom Research Assessment Exercise. The authors found an increase in research quality across the two time periods. The current review is more narrowly targeted (i.e. publications), but equally interested in establishing whether there is evidence of a growing research capacity among social workers working in TBI.

A scoping review can identify the range and nature of research activity; collate and communicate findings about a body of research; and identify gaps within the existing literature (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005; Levac, Colquhoun, & O'Brian, 2010). Employing a scoping methodology, the current review sought to (i) identify the output in peer-reviewed publications that social workers have generated in the field of TBI, (ii) ascertain its impact and (iii) evaluate its quality.

2 METHODS

The review followed five steps: (i) identifying the research question, (ii) identifying relevant studies, (iii) study selection, (iv) charting the data and (v) analysing/summarising the study description data. Although not required by the scoping methodology, studies that had collected empirical data also underwent a quality appraisal process (details provided below). Addressing study quality is an important element in evidence-based or evidence-informed practice (Taylor, Dempster, & Donnelly, 2007) and in the current study, helped evaluate the credibility of the current body of evidence.

2.1 Identifying research question

The first step involved specifying the parameters of the review in terms of the concept, population and outcomes (Levac et al., 2010). Conceptually, the evidence base was defined as the published work produced by social workers about TBI. A social work contribution was defined as at least one author of any eligible publication having a social work qualification. This approach is consistent with previous reviews of social work research outputs in other domains (e.g. Brough et al., 2013; Crisp, 2000; Tilbury, Hughes, Bigby, Fisher, & Vogel, 2017; Tilbury, Hughes, Bigby, & Osmond, 2017).

The review aimed to be international in scope and encompass both discipline-specific work as well as work produced as part of interdisciplinary collaboration. To be broadly inclusive, a research typology was adopted that had been developed in the United Kingdom to generate an evidence base for the National Service Framework (NSF) on Long-Term Conditions (Department of Health 2005) as applied to neurological conditions (Turner-Stokes, Harding, Sergeant, Lupton, & McPherson, 2006). This NSF typology recognised the value of heterogeneous research designs (primary research, secondary research and review-based research) as well as expert evidence in contributing to a comprehensive evidence base (more details provided below), and has been employed in previous systematic reviews in the field of TBI (Fadyl & McPherson, 2009).

INSWABI members primarily work with those under 65. Therefore, the population for the study was limited to adults of working age with TBI, with studies of people aged older than 65 years excluded from this study. Children aged 0–17 years will be the subject of a separate review. Finally, the outcomes investigated in the current review comprised the output, impact and quality of the published literature. Each of these outcome areas are detailed below.

2.2 Identifying relevant studies

Relevant studies were identified through a three-pronged search strategy. Greenhalg and Peacock (2005) identified the value of integrating protocol-driven, snowballing and personally based search strategies to maximise the results for a review. The protocol-based elements of the current review comprised a search of the following electronic databases and search engines: Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, ASSIA; Current Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, CINAHL; IBSS (International Bibliography of the Social Sciences); PsycINFO; PubMed; Scopus; SocIndex; Social Services Abstracts; Social Work abstracts; and Web of Science. Three search terms covering the population group and the profession were employed in combination with the BOOLEAN operators (head injur* OR brain injur* AND social work). A limiting function was employed to select items published in English. In addition to the database search, a hand search was conducted of the contents of relevant social work journals (Health and Social Work; Journal of Social Work in Disability and Rehabilitation; Social Work in Health Care; British Journal of Social Work; and Australian Social Work) and a search was also conducted on Google Scholar.

For the snowballing, iterative searches were conducted of the reference lists of works identified by the first phase database searches, and author tracing was undertaken to ascertain whether additional studies had been published by authors who had works identified in the first phase. Finally, the personal-based strategies involved (i) an e-mail consultation with INSWABI to identify articles that members had come across in the course of their practice and (ii) serendipity, described by Greenhalg and Peacock as “finding a relevant paper when looking for something else” (2006, p. 1064).

2.3 Study selection

Identified works were selected if they met the inclusion criteria: (i) a chapter, book or an article published in a peer review journal, (ii) with a focus on TBI, (iii) among people aged 18–65, (iv) authored or co-authored by a social worker and (v) published between 1970 and 2014. The decade of the 1970s was chosen as the starting point because the first specialist TBI rehabilitation programmes were established internationally during this decade (Rosenthal, 1996). The review selected four decade periods (1975–1984, 1985–1994, 1995–2004 and 2005–2014) so that the trajectory of publication trends could be analysed over a manageable number of comparable units of time. Studies that spanned a broader range of disability groups were included if they either (i) reported discrete data for the TBI group or (ii) for non-empirical reports, TBI was explicitly addressed in discrete sections of the paper. Exclusion criteria included non-peer-reviewed citations such as editorials, commentaries, book reviews, letters, unpublished abstracts, letters and conference abstracts.

Two authors (AM, GS) independently screened the titles and abstracts of the citations against the inclusion/exclusion criteria which were then compared. Citations for which a decision could not be made or for which there was disagreement underwent a second stage of screening. The full text of the citation was obtained and the two authors reviewed the citation, making a final decision about inclusion/exclusion by consensus.

2.4 Data charting

Descriptive data were collected about the selected studies. A template was devised to collect information on several domains (using descriptors adapted from Coren & Fisher, 2006). These were the type of study, field of practice, focus of practice, year of publication, country in which the study was conducted, category of publication (book, chapter and article), whether a social worker was the lead (first) author and whether the study was interdisciplinary.

To ascertain impact, data were collected on the number of citations, the type of journal in which the articles were published (i.e. social work, rehabilitation, and others), and whether articles were cited by other social workers. The number of citations was determined by reference to Google Scholar (data extracted on 31 December 2016). The extent to which works cited previous works by social work authors was determined by a search of the reference lists of the selected studies.

2.5 Summarising, analysing and evaluating studies

Data on the study descriptors were tabulated. Studies were grouped into five key fields of practice (family, social inclusion, inequalities, psychological adjustment and military). A small number of publications provided an overview of the field of TBI, often spanning a number of these fields of practice. To investigate characteristics of the output and impact of identified works (aims i and ii), descriptive and between-groups statistical tests were utilised. Given the type of data, chi-square and non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney U, Kruskal-Wallis) were employed.

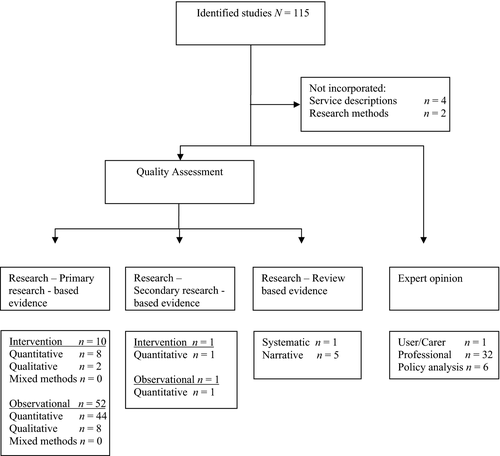

To undertake the quality evaluation (aim iii), the quality assessment framework developed as a companion to the NSF research typology was employed (Turner-Stokes et al., 2006). For this review, the first step involved sorting the identified works into the NSF typology categories: primary research-based evidence, secondary evidence, reviews and expert accounts (see Figure 2 below for more detail).

One refinement of the typology was made at this step. Specifically, among studies grouped in the primary research-based evidence category, observational studies were also included in addition to intervention studies. Observational studies were further classified by the research design (e.g. cohort, cross-sectional, etc.). Prior to conducting the quality appraisal, data on additional descriptors were collected for the intervention studies, namely the research design, sample size, type of intervention, mode of delivery and outcomes.

Having sorted the studies, the primary research-based studies, secondary research-based studies and the reviews were assessed using the five quality criteria specified by Turner-Stokes et al. (2006), scoring 0 (not achieved), 1 (partially achieved) or 2 (achieved) for each criterion, giving a total score between 0 and 10. Studies are then classed as high (7–10), medium (4–6) or low (scores of 3 or less) quality. In the original development of this method, the quality rating scale was found to have good inter-rater reliability (Turner-Stokes et al., 2006).

For the review, a template with the five quality criteria was developed, and descriptors for each criterion were generated to improve inter-rater reliability. Employing the template, independent ratings were conducted for the relevant works identified as primary research or review-based research by two of the following three authors (AM, GS and MV). Raters could not evaluate studies on which they had been authors. The kappa statistic (Landis & Koch, 1977) was used to determine the level of inter-rater agreement across all pairs of ratings of the overall quality of the works (low, medium and high). In the case of disagreements, the final rating was resolved by consensus through consultation with the third rater.

Following the procedures specified by Turner-Stokes et al. (2006), the expert professional accounts were not subjected to quality evaluation, but their level of citation was recorded as an indication of their relative impact (0 citations = none, 1 to 10 citations = low and greater than 10 citations = moderate to high). The publications produced by professional users and the policy-related publications were aggregated. Through consensus discussion, they were classed into field of practice by two authors (GS and AM).

3 RESULTS

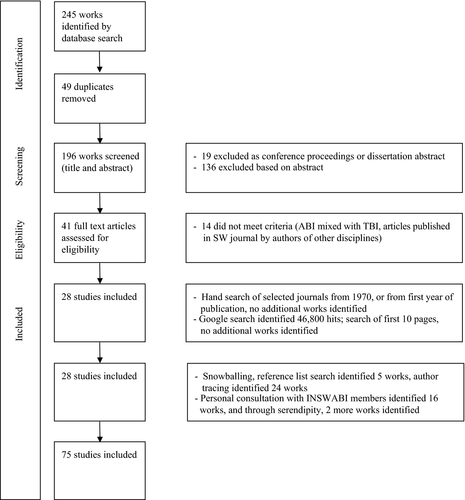

The search results are displayed in Figure 1. The original phase of the search (1975–2009) was conducted between July 2012 and June 2013. After duplicates were removed, and screening conducted, a total of 28 relevant works were identified through the protocol-driven strategies (ASSIA, 11; CINAHL, 2; PsycINFO, 22; SocIndex, 5; SCOPUS, 2; and Social Services Abstracts, 1). Two additional works were identified through hand searching the specified journals. Similarly, a total of 4,680 results were elicited by the search of Google Scholar but no new works were identified. One outlying and seminal article (Romano, 1974), identified as the first social work authored paper addressing the field of TBI, was added to the decadal period 1975–1984. A total of 47 additional works were identified through the second-phase snowballing and person-based strategies, culminating in a final total of 75 published works.

A supplementary search to update the review to 2014 was conducted in June 2015, employing the same search terms and search strategy. An additional 40 items were identified, two items that were published prior to 2009 but not identified in the original search, and 38 new items published between 2010 and 2014. Items were identified through PsycINFO (n = 15), PubMed (n = 5), hand searching journals (n = 2) and author tracing (n = 18), with no additional items identified through the other databases or search strategies.

3.1 Aim (i) publications output

Data on the output descriptors are displayed in Table 1. In terms of study type, more than half of the articles were empirical (53.7%, 64/115). The works covered four established fields of practice and one emerging field of practice (i.e. military) (see Table 2). In addition, a number of overview papers covered more than one field of practice.

| Descriptors | Data |

|---|---|

| Output | |

| Type of study (n, %) | |

| Primary research | |

| Intervention | 10, 8.7 |

| Observational | 52, 45.3 |

| Secondary research | 2, 1.7 |

| Reviews | 6, 5.2 |

| Expert account | |

| User opinion | 1, 0.9 |

| Professional opinion | 32, 27.8 |

| Other | |

| Policy analysis | 6, 5.2 |

| Research methods | 2, 1.7 |

| Service descriptions | 4, 3.5 |

| Year of publication (n, %) | |

| 1975–1984a | 2, 1.7 |

| 1985–1994 | 19, 16.5 |

| 1995–2004 | 33,28.7 |

| 2005–2014 | 61,53.0 |

| Country of publication (n, %) | |

| Australia | 42, 36.5 |

| United Kingdom | 13, 11.3 |

| United States | 48, 41.7 |

| Other countriesb | 12, 10.4 |

| Category of publication (n, %) | |

| Book | 1, 0.9 |

| Chapter | 13, 11.3 |

| Journal article | 101, 87.8 |

| Social worker lead author, yes (n, %) | 77, 67.0 |

| Interdisciplinary, yes (n = 106; n, %)c | 71, 67.0 |

| Impact | |

| Citations (median, IQR) | 15.0, 25.0 |

| Type of journal (n = 96) (n, %) | |

| Social work | 28, 27.7 |

| Rehabilitation | 57, 56.4 |

| Other journald | 16, 15.8 |

| Cited by other social worker, yes (n, %) | 69, 60.0 |

- a The only paper published earlier than 1975 that met the search criteria has been aggregated into this category.

- b India n = 5; Canada n = 1; Sweden = 2; Israel n = 3; South Africa n = 1.

- c n = 9 single author publications.

- d Social Science and Medicine n = 2; Psychiatric Medicine; Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine; Neurology India; Indian Journal of Social Psychology; Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health; Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Neuropsychiatry; Acta Neurologica Scandinavica; Journal of Clinical Psychology; Medical Journal of Australia; The Journal of Adult Protection; Families in Society; Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health; Home Health Care Services Quarterly; PLOS-One.

| Study type | Total n (%) | Family n (%) | Social inclusion n (%) | Inequalities n (%) | Psychological adjustment n (%) | Military n (%) | Overview n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | 10 | 1 (3.0) | 4 (13.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (21.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Observational—quantitative | 44 | 18 (54.5) | 14 (48.3) | 3 (27.2) | 9 (39.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Observational—qualitative | 8 | 2 (6.1) | 2 (6.9) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) |

| Secondary analysis | 2 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.4) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Review | 6 | 5 (15.2) | 1 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Experta | 38 | 7 (21.2) | 7 (24.1) | 6 (54.5) | 7 (30.4) | 5 (100.0) | 6 (85.7) |

| Totalb | 108 | 33 (100.0) | 29 (100.0) | 11 (100.0) | 23 (100.0) | 5 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) |

- a Expert category includes the “professional user” and “policy-related” publications as defined in Table 1.

- b Papers not classified by Field of Practice n = 1 user opinion, n = 4 service description and n = 2 research methods.

Fields of practice relating to families, social inclusion and psychological adjustment accounted for approximately three quarters of the total number of papers produced (see Table 2). The pattern of papers by field of practice varied over the four decades; the first two decades predominantly produced publications focused on families and psychological adjustment. Publications analysing inequalities started to appear from 1995, and the military publications only in the latest decade. There was a constant number of overview publications produced across each decade.

There was a significant increase in the number of articles published in the most recent decade (53.0%, 61/115), doubling the output of the previous three decades combined. Together, the United States and Australia produced four-fifths of all output (78.2%, 90/115). There were significant differences in publishing patterns (χ2 = 18.0, df = 6, p = .006). Australian authors were most likely to publish in rehabilitation journals (75.0%, 30/40 Australian journal publications), whereas a larger proportion of authors from the United States (35.7%, 15/42 journal publications) and the ‘other countries’ group (50%, 6/12 journal publications) published in social work journals. In the United Kingdom, almost half of the publications were chapters as well as the sole book (46.2%, 6/13), with seven journal publications.

A social worker was the lead author in over two-thirds of the publications and a similar proportion of publications that had more than one author involved at least one interdisciplinary collaborator (see Table 1). The United Kingdom had the lowest number of publications involving interdisciplinary collaborations (33.3%; 3/9 published with more than one author), in contrast to Australia (75.6%, 31/41), the United States (68.2%, 30/44) and the ‘other countries’ group (58.3%, 7/12). However, these differences were not statistically significant. Disciplines most frequently involved in collaborative publishing were psychology, medicine (neurology, rehabilitation and psychiatry), occupational therapy, speech pathology and nursing.

3.2 Aim (ii) publication impact

Most works had been cited one or more times (89.6%; 103/115). Articles with social workers as lead author had fewer citations (median 15.0, IQR 21.0) than articles in which someone from another discipline was lead author (median 16.5, IQR 46.0), but the differences was not statistically significant (Mann–Whitney U). Articles published in social work journals (median 6.0, IQR 17.0) were cited significantly less often (χ2 = 11.6, df = 2, p = .003, Kruskal-Wallis) than citations for journal articles published in rehabilitation (median 18.0, IQR 20.0) or the ‘other’ category of journals (median 20.0, IQR 41.0).

Citations for the book and book chapters (median 1.5, IQR 5.0) were significantly lower (U = 201.5.0, p = .001, Mann–Whitney U) than journal articles (median 16.0, IQR 24.0). Finally, social work authors frequently cited works by other social workers within the field, with two-thirds citing one or more of the publications identified in this review (see Table 1).

3.3 Aim (iii) quality evaluation

Articles included in the quality evaluation are outlined in Figure 2. Works not included comprised four service descriptions (Lees, 1988; Trumble, 1981; Tyerman & Booth, 2006; Vandiver, Johnson, & Christofero-Snider, 2003), two works on research methods (Egan, Worrall, & Oxenham, 2005; Higham, 2001), six policy analysis papers (Cole, Cecka, & Smith, 2012; Cole & Cecka, 2014; Foster et al., 2002; Foster & Tilse, 2003; Foster, 2004, 2007) and the expert papers (professional, user/carer; n = 33).

The remaining 70 studies were aggregated into primary research (intervention, observational), secondary research and reviews (see Figure 2). The level of inter-rater agreement by the authors (AM, GS and MV) on the quality ratings (high, medium and low) for the publications was very strong over the 70 pairs of ratings (κ = 0.85, p < .001), within the band of excellent inter-rater agreement (κ > 0.75; Landis & Koch, 1977).

3.3.1 Intervention studies

The 10 intervention studies (see Table 3) included a variety of research designs, ranging from a randomised controlled trial through to a single case study, with half published in the last decade (2005–2014). Four studies evaluated service-level outcomes; two involved a multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme that included social workers (Sabhesan, Arumugham, Ramaswamy, Athiappan, & Natarajan, 1993; Simpson et al., 2004) and one from a social work specific programme (Albert, Im, Brenner, Smith, & Waxman, 2002). The other seven studies evaluated specific interventions. Four of these were interdisciplinary in nature, involving social work jointly delivering the intervention in collaboration with other health professionals (Dahlberg et al., 2007; Egan et al., 2005; Simpson, McCann, & Lowy, 2003), or social workers as one of several health professionals individually delivering the same intervention (Vungkhanching, Heinemann, Langley, Ridgely, & Kramer, 2007). The remaining studies documented interventions delivered by social workers (Moore et al., 2014; Rowlands, 2001ab; Simpson, Tate, Whiting, & Cotter, 2011).

| Source | Field of practice/focus | Research design | Sample size | Intervention | Delivery mode and settinga | Outcome/s | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sabhesan et al., 1993; India |

Psych adjustment/behaviour | Uncontrolled cohort study, pre and postb | N = 101 | Multidisciplinary programme delivered by neurosurgeon, psychiatrist, psychologist and social workers |

Individual hospital outpatient programme + quarterly home visits Community |

Significant reduction in mental health pathology and improved sexual function; but irritability, amotivation and disinhibited behaviour did not improve | Low |

|

Rowlands, 2001b; Australia |

Social inclusion/social support network | Case seriesc | N = 10 | Circles of support intervention to build social networks | Group, Community | Decreased social isolation, increased social networks | High |

|

Albert et al., 2002; USA |

Family | Controlled cohort studyb | N = 27 | Social work liaison service for families after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation | Individual, phone follow-up, Community | Decreased carer burden scores, increased mastery and satisfaction | Medium |

|

Simpson, McCann, & Lowy, 2003; Australia |

Psych adjustment/sexuality | Single case experimental designb | N = 1 | Topical anaesthetic + behavioural/educational approaches | Individual, face to face plus phone follow-up, Community | Resolution of problem with premature ejaculation | High |

|

Simpson et al., 2004; Australia |

Social inclusion/community re-integration | Uncontrolled cohort study, pre and postb | N = 50 | Multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme including social work | Individual and group, Post-acute residential programme, Community | Significant increase in measures of community/social participation and independent living skills | High |

|

Egan, Worrall, & Oxenham, 2005; Australia |

Social inclusion/Internet access | Case series, pre- post designc | N = 7 | Internet skills training programme | Individual, each linked with volunteer tutor, Community | 6/7 participants achieved moderate to high degrees of independence in internet usage | High |

| Vungkhanching, Heineman, Langley, Ridgely, & Kramer, 2007; USA | Psych adjustment/substance misuse | Case series with non-equivalent controlb | N = 117 | Skills-based motivational interviewing intervention | Individual counselling sessions, Community | Significant decrease in alcohol/drug use, increase in coping skilfulness, increase likelihood to maintain employment | High |

| Dahlberg et al. 2007; USA | Social inclusion/social competency | Clinical controlled trialb | N = 52 | Social skills training programme |

Group, face to face Community |

Significant improvements in communication competency, goal attainment and satisfaction with life | High |

| Simpson, Tate, Whiting, & Cotter, 2011; Australia | Psych adjustment/behaviour | Randomised controlled trialb | N = 17 | Cognitive behaviour therapy programme | Group, face to face, Community | Treatment group significant decrease in hopelessness compared to a group receiving usual care | High |

| Moore et al. 2014; USA | Psych adjustment/behaviour | Case series, pre-post design with historical controlb | N = 64 | SWIFT-Acute programme targeting the cognitive, emotional and behavioural risk factors for development of persistent post-concussive symptoms | Individual session face to face, Hospital Emergency Department | Tx group reported significant reduction in alcohol use while usual care group showed no change (pre vs post); Tx group showed no change in community integration while usual care group showed significant reduction (pre vs post) | High |

- a All interventions delivered within health setting with exception of Egan et al., 2005, which was delivered from a university setting.

- b Quantitative.

- c Qualitative.

In nine of the 10 studies, the person with the TBI was the target of the intervention, and the family caregiver in the other study. The practice areas reflected the dominant psychosocial focus of social work practice in the field. The modalities of intervention ranged across counselling, psycho-education, the provision of a multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme that included social work, skills-based training and a social work liaison programme. The majority of interventions were delivered by social workers in health settings but participants in all but one study (Moore et al., 2014) were community-based. Programmes were delivered on an individual basis in six studies, in a group-based format in another three and in one study a mix of both. Interventions were primarily delivered face to face, but four studies incorporated phone-based delivery as the sole mode of service delivery or in combination with face-to-face delivery.

For the person with TBI, reported outcomes from the interventions included improved psychological well-being, improved sexual function, reduced psychopathology, reduced hopelessness, increased levels of skills, reduced alcohol intake and increased independence in community participation/integration. Similarly, the family members reported decreased burden and increased levels of psychological well-being. Eighty per cent of the studies were rated in the high research quality band (Turner-Stokes et al., 2006).

3.3.2 Observational studies

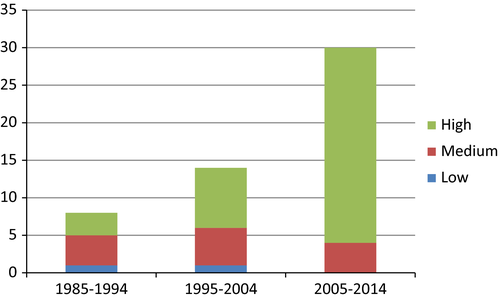

The number and quality of observational studies has increased steadily over the past three decades, with just over half 57.7% (30/52) published in the most recent decade. Furthermore, over 80% (86.7%; 26/30) of the articles published since 2004 were rated as high quality, significantly better than the preceding two decades (1984–1995 vs 1995–2004 vs 2005–2014; χ2 = 10.16, df = 4, p = .039; see Figure 3).

A range of research designs were employed including case–control (n = 1); cohort (n = 15); cross-sectional studies (n = 24) of which a subset employed a case comparison between different sub-groups of people with TBI (6/24); non-consecutive case series (n = 8); psychometric (n = 3); and one ecological study (see Table 4). A total of 44 of the 52 studies employed quantitative methods with the remainder employing qualitative methods (see Table 4). The studies were grouped by field of practice (family, social inclusion, psychological adjustment, and health inequalities) and then sub-categorised by the focus of the publication within the field of practice. Studies were then ranked by their quality rating (see Table 4).

| Focus | Design | Quality rating | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Field of practice: family | |||

| Caregiver outcomes | Cohort | High | Hall et al., 1994; Nalder, Flemming, Foster, Cornwell, & Shields, 2012 |

| Medium | Sabhesan, Ramasamy, Athiappan, & Natarajan, 1991; Sabhesan, Ramasamy, Andal, & Natarajan, 1987 | ||

| Cross-sectional | High | Anderson, Simpson, Mok, & Parmenter, 2006; Winstanley, Simpson, Tate, & Myles, 2006; Anderson et al., 2009; Anderson, Simpson, & Morey, 2013; Simpson & Jones, 2013; Dillahunt-Aspillaga et al. 2013 | |

| Low | Resnick, 1993 | ||

| Case comparison | High | Ben Arzi, Solomon, & Dekel, 2000 | |

| Adult siblings of people with TBI | Cross-sectional | High | Degeneffe & Lynch, 2006; Degeneffe & Olney, 2008 |

| Non-consecutive case series | High | Degeneffe & Lee, 2010a; Degeneffe & Olney, 2010a | |

| Scale development | Psychometric | High | Degeneffe, Chan, Dunlap, & Man, 2011 |

| Family impact on person with TBI | Cross-sectional | High | Barclay, 2013 |

| Domestic violence | Case comparison | Medium | Monahan & O'Leary, 1999 |

| Child abuse | Case–control | High | Vliet-Ruissen, McKinlay, Taylor, 2014 |

| Field of practice: social inclusion | |||

| Vocational re-entry | Cohort | High | Keyser-Marcus et al., 2002; Rietdijk, Simpson, Togher, Power, & Gillett, 2013 |

| Cohort | Medium | Sabhesan, Armugham, Ramasamy, Andal, & Natarajan, 1988 | |

| Independent accommodation | Case comparison | High | Brzuzy & Corrlgan, 1996 |

| Case comparison | Medium | Brzuzy & Speziale, 1997 | |

| Community re-integration | Cohort | High | Tate, Lulham, Broe, Strettles, & Pfaff, 1989; Nalder, Flemming, Cornwell, Foster, & Haines, 2012 |

| Cross-sectional | High | Nalder, Flemming, Cornwell, & Foster, 2012 | |

| Non-consecutive case series | High | Nalder, Flemming, Cornwell, Shields, & Foster, 2013a | |

| Psychometric | High | Tate, Simpson, Soo, & Lane-Brown, 2011 | |

| Service utilisation | Cross-sectional | Low | Jackson & Tangney, 1997 |

| Social competence | Cohort | High | Dahlberg et al., 2006 |

| Gender disparities | Non-consecutive case series | Medium | Alston, Jones, & Curtin, 2012a |

| Cross-cultural adjustment | Non-consecutive case series | High | Simpson, Mohr, & Redman, 2000a |

| Goal setting | Case comparison | High | Simpson, Foster, Kuipers, Kendall, & Hanna, 2005 |

| Psychosocial risk scale | Psychometric | Medium | Watts & Perlesz, 1999 |

| Field of practice: health inequalities | |||

| Equity of access | Cohort | High | Foster, Fleming, Tilse, & Rosenman, 2000 |

| Cross-sectional | High | Foster et al., 2004 | |

| Incidence of TBI | Population-based study | Medium | Tate, McDonald, & Lulham, 1998 |

| Mortality trends | Cohort | High | Baguley et al., 2012 |

| Field of practice: psychological adjustment | |||

| Behaviour | Cohort | High | Simpson, Blaszczynski, & Hodgkinson, 1999 |

| Case comparison | High | Simpson, Tate, Ferry, Hodgkinson, & Blaszczynski, 2001 | |

| Cross-sectional | High | Simpson, Sabaz, & Daher, 2013; Sabaz et al., 2014; Simpson, Sabaz, Daher, Gordon, & Strettles, 2014 | |

| Adjustment | Cohort | High | Tate, Broe, & Lulham, 1989 |

| Non-consecutive case series | Medium | Strandberg, 2009aa; Strandberg, 2009ba | |

| Sexual adjustment | Cross-sectional | High | Simpson & Long, 2004 |

| Spirituality | Cross-sectional | High | Johnstone, Yoon, Rupright, & Reid-Arndt, 2009 |

| Substance misuse | Controlled cohort study | Medium | Sabhesan, Arumugham, Ramasamy, & Natarajan, 1987 |

| Field of practice: overview | |||

| Overview | Cross-sectional | High | Buck, Sagrati, & Kirzner, 2013 |

- a Qualitative studies; Ecological was population-based study; Case comparison studies were cross-sectional studies in which people with TBI and/or family members were compared on the presence or absence of some psychosocial characteristic (e.g. living independently vs not living independently).

3.3.3 Secondary analysis

Two papers within the last decade (2005–2014) conducted a secondary analysis of data. The fields of practice for the studies were social inclusion and inequalities respectively. The first study compared outcomes for people with TBI from four different post-acute brain injury rehabilitation programmes, analysing data collected by programmes belonging to the Pennsylvania Association of Rehabilitation Facilities (Eicher et al., 2012). The second study (Linton & Kim, 2014) analysed data from the Arizona Trauma Database to investigate the possibility of race-based differences (among white people, black people, Native American, Asian, other races) in the aetiology of TBI, with a particular interest in whether the non-white racial groups had a higher incidence of violence-related TBI. Both publications were rated as high quality.

3.3.4 Reviews

Six reviews were identified. These included one systematic and five narrative reviews. The systematic review examined the research literature published between 2007 and 2012 investigating suicide ideation and behaviours after TBI (Bahraini, Simpson, Brenner, Hoffberg, & Schneider, 2013). Among the narrative reviews, two focused on the literature addressing the impact of TBI on families (Bishop, Degeneffe, & Mast, 2006; Degeneffe, 2001); one on the work–life balance of culturally diverse caregivers of people with TBI (Cole et al., 2012); one provided a global introduction to the field (Resnick, 1994); and with the final one reviewing the literature on building social support after TBI (Rowlands, 2000). The quality scores for all reviews were rated in the low category, with the one exception of the systematic review (High).

3.3.5 Expert opinion

One expert user account was identified. Perry (1986), who sustained a severe TBI while driving to a social work home visit, recounts the personal challenges associated with his recovery, rehabilitation and community re-integration. Perry highlighted three primary causes of distress and provided suggestions for their effective management by professionals (Table 5).

| Sources of distress | Recommended interventions for professionals |

|---|---|

| Initial disorientation |

Provide timely information sensitively Communicate hard-to-accept truths, but carefully and at the patients’ own pace |

| Symptoms and social losses | Provide emotional support and stress management. Stress management can include behavioural contracts, pacing, exercise, medication, biofeedback, creative projects and organisational skills |

| Extended disorganisation in mourning |

Provide ongoing psychotherapy to integrate the experience (pre-injury and post-injury) After hospitalisation, counselling approaches need to support both the family as well as the patient; with a goal of working to enable the patient and family to be able to eventually reinterpret the devastating experience as one with beneficial aspects. Providing support to ensure good family mental health, which is essential for the optimum psychosocial recovery of the patient. |

Finally, the publications that represented expert opinion or policy analyses were grouped by field of practice and then by number of citations (see Table 6). Overall, the expert papers were distributed across all three groupings of citations. The policy papers were all concentrated in the area of inequalities, addressing health-related (equity of access from acute care to inpatient rehabilitation) and disability-related issues (people with TBI's access to Employee Assistance Programmes on return to the workplace; organisational responses that could support the work–life mix for carers from minority backgrounds who were supporting relatives with TBI).

| Field of practice | Greater than 10 citations | 1–9 Citations | 0 Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Romano, 1974; McLaughlin & Schaffer, 1985; Romano, 1989; Tyerman & Booth, 2001 | Booth, 2006; DeHope, 2006 | Resnick, 1993; Degeneffe & Lee, 2014 |

| Social inclusion | Higham & Phelps, 1998; Levesque, 1988; Mantell, 2010; Rowlands, 2001a,b; Wiseman, 2011; Holloway, 2014; | Greaves, Neary, & Warren, 2006; | |

| Health inequalities | Foster & Tilse, 2003a; Foster, 2007a | Foster et al., 2002a; Cole & Gary, 2012a | Foster, 2004a; Cole & Cecka, 2014a |

| Psychological adjustment | DeHope & Finegan, 1999; Forssmann-Falck, Christian, & O'Shanick, 1989; Simpson, 2001; | Forssmann-Falck & Christian, 1989; Mallon & Houtstra, 2007; Futeral, 2005 | Dean & Parker, 2006; |

| Military | French & Parkinson 2008 | Speziale, Kulbago, & Menter, 2010; French, Parkinson, & Massetti, 2011; Parkinson, French, & Massetti, 2012; | Smith-Osborne, 2013; |

| Overviews | Buck, 2011; Baker, Tandy, & Dixon, 2002; Carlton & Stephenson, 1990; Simpson et al., 2002; | Moore, 2013; | Lees, 1988 |

- a Policy (n = 6) references.

4 DISCUSSION

Overall, the results demonstrated a significant upwards trajectory in knowledge production undertaken by social workers in the field of TBI. This growth was documented in the output, impact and quality of the published research across four decadal periods. The number of publications has more than quintupled since the earlier review by Carlton and Stephenson (1990). Not only has there been a substantial increase in the quantity of works but also in the quality of the research-based papers, reflecting broader developments within the profession internationally (Simpson & Lord, 2015a,b; Thyer & Myers, 2011).

The fields of practice that have been the focus of social work scholarship reflect the concerns of the profession more generally. ‘Families’ and ‘social inclusion’ situate the individual within the systems and relationships that are a primary concern of social work practice (Mantell, 2013a). Inclusion and health inequality both represent social work's commitment to principles of ‘social justice’ and ‘empowerment’ (The International Federation of Social Workers 2014). In contrast, the work on psychological adjustment for individuals and their families highlight possible variations in social work roles internationally. While in some countries, such as Australia and United States, the social work role incorporates therapeutic practice (e.g. Bronstein, Kovacs, & Vega, 2007; Brough et al., 2013; Judd & Sheffield, 2010), in the UK, there has been a significant shift to co-ordinating, managing and allocating resources (Mantell, 2013b). One use of the review, therefore, can be to enable practitioners to access skills or programmes from the wider international body of social work knowledge and then adapt them to the local practice environment.

The majority of publications were research-based. A past criticism of social work scholarship has been that it focused too heavily on theoretical or conceptual papers at the expense of empirical research (Crisp, 2000). However, the review identified strong growth in research-based papers, with such publication types in the majority for the two most recent decadal periods (1995–2004 and 2005–2014). The high number of collaborative interdisciplinary papers reflects the growing international trend towards inter-professional practice capabilities within the health sector as well as interdisciplinary research within disability studies (Matthews et al., 2011; Strandberg, 2015; World Health Organisation, 2010).

Another concern about the broader research output of the profession has been the disproportionate number of descriptive papers versus work evaluating practice (Soydan, 2015). The current review found a similar picture, with only 10 of the 59 empirical papers reporting intervention studies. However, the fact that half were published in the latest decadal period suggests a growth in publications evaluating interventions/practice.

The evaluated interventions varied more broadly than programmes developed specifically for social work and best delivered by social workers. In the environment of interdisciplinary care, social work interventions may be developed that exploit complementary partnerships with other allied health in the joint provision of programmes (e.g. social worker provides the relationship component to supplement a speech pathologist's language component in a social skills group). In addition, role blurring (Gray & White, 2012; Vungkhanching & Tonsing, 2016) refers to situations in which more than one professional can potentially undertake a task (e.g. social work or occupational therapy undertaking case management). In such situations, if other professions are implementing interventions developed by social work, this is giving an implicit clinical leadership role to the profession.

The focus for systematic reviews has been steadily expanding to address a wider range of study types and issues (Crisp, 2015) with the value of observational studies receiving greater recognition (Mallen, Peat, & Croft, 2006). In this review, the majority of observational studies were cross-sectional or non-consecutive case series, the weaker research designs. Future research could seek to increase the number of controlled or cohort studies. Considering the findings in relation to impact, works published in rehabilitation journals were cited more highly than those in social work journals. Given that brain injury is a highly specialised field within the broad spectrum of social work, this difference may reflect the greater salience of the work within the specialty journals in the field.

There were a number of limitations with the review methodology. First, it was difficult to reliably and consistently identify social work authors, and so there may be other publications that were not identified, leading to an underestimate of the extent of the evidence base. Similarly, the search terms used were those most prevalent within social work practice, but this could also have led to the omission of some studies. Moreover, by focusing on TBI, a number of studies that included mixed samples of TBI and other types of acquired brain injury could not be included (e.g. Brown et al., 1999; Charles, Butera-Prinzi, & Perlesz, 2007).

Despite the limitations, the review identified a significant body of research. Knowledge production then lays the groundwork for knowledge use or implementation in practice (Gray, Joy, Plath, & Webb, 2012). The great majority of the studies were undertaken in community settings (e.g. 9 of the 10 intervention studies). This has the potential of simplifying the process of knowledge transfer (i.e. research findings produced in one location being transferred to another context of use, Gray et al., 2012, p. 157) given that more than half of social workers working in the field are employed in outpatient and/or community settings (Vungkhanching & Tonsing, 2016). The observational studies documented the extent and causes of psychosocial disadvantage following TBI through the many dimensions of family, social inclusion/exclusion, health inequalities and psychological adjustment. This can build practitioner awareness of psychosocial needs that need assessment, as well as be a resource for client/family education and help drive broader advocacy.

Fisher and Marsh (2003) argued that social work research lacks the critical mass of researchers to be able to generate new knowledge and research-based practice. In order to ensure the momentum of the upward trajectory found in this review, e-networks such as INSWABI can continue to provide a mechanism for academic and research collaboration among established and early career researchers in TBI (Lunt, Ramian, Shaw, Fouché, & Mitchell, 2012). Adopting an academic–practitioner model with a focus on practice-research can ensure that future work is clinically relevant, with a focus on developing and evaluating intervention, while also providing pathways for building research capacity among social work practitioners (Joubert, 2006; Joubert & Hocking, 2015). The ‘expert accounts’ represent a distillation of practice wisdom (Chu & Tsui, 2008) and provide a fertile set of practice-based experiences, insights and ideas ready for future evaluation (Fawcett & Pocket, 2015). Finally, the review provides a benchmark against which the next decade of social work scholarly activity within the field of TBI can be compared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Michelle Lefevre for comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.