Improving hospital discharge arrangements for people who are homeless: A realist synthesis of the intermediate care literature

Funding Information

This realist synthesis was funded by the National Institute of Health Research as the first stage of a 2-year comparative study of hospital discharge arrangements for homeless people in England. The review stage was completed between September 2015 and March 2016. Ethics approval for the study was secured from the National Research Ethics Committee [REC Ref: 16/EE/0018].

Abstract

This review presents a realist synthesis of “what works and why” in intermediate care for people who are homeless. The overall aim was to update an earlier synthesis of intermediate care by capturing new evidence from a recent UK government funding initiative (the “Homeless Hospital Discharge Fund”). The initiative made resources available to the charitable sector to enable partnership working with the National Health Service (NHS) in order to improve hospital discharge arrangements for people who are homeless. The synthesis adopted the RAMESES guidelines and reporting standards. Electronic searches were carried out for peer-reviewed articles published in English from 2000 to 2016. Local evaluations and the grey literature were also included. The inclusion criteria was that articles and reports should describe “interventions” that encompassed most of the key characteristics of intermediate care as previously defined in the academic literature. Searches yielded 47 articles and reports. Most of these originated in the UK or the USA and fell within the realist quality rating of “thick description”. The synthesis involved using this new evidence to interrogate the utility of earlier programme theories. Overall, the results confirmed the importance of (i) collaborative care planning, (ii) reablement and (iii) integrated working as key to effective intermediate care delivery. However, the additional evidence drawn from the field of homelessness highlighted the potential for some theory refinements. First, that “psychologically informed” approaches to relationship building may be necessary to ensure that service users are meaningfully engaged in collaborative care planning and second, that integrated working could be managed differently so that people are not “handed over” at the point at which the intermediate care episode ends. This was theorised as key to ensuring that ongoing care arrangements do not break down and that gains are not lost to the person or the system vis-à-vis the prevention of readmission to hospital.

What is known about this topic

- Long-term homelessness is characterised by “tri-morbidity” (the combination of mental ill-health, physical ill-health, and drug and alcohol misuse).

- Hospital discharge is often problematic for people who are homeless with high rates of readmission.

- Much is known about the design and delivery of intermediate care services for older people, but less is known about how to meet the transitional care needs of people who are homeless.

What this paper adds

- A synthesis of “what works and why” in the design and delivery of specialist intermediate care services for people who are homeless

- New knowledge from the field of homelessness as to how intermediate care for all service user groups might be strengthened. For example, the need to encompass longer term health and well-being goals alongside those for “physical reablement”.

- A reconceptualisation of the intermediate care concept which is designed to prevent these short-term services from becoming “blocked”.

1 INTRODUCTION

This article reports the findings of a realist synthesis of what works and why in intermediate care for people who are homeless. The overall aim was to fill a gap by updating and expanding an earlier synthesis of intermediate care that did not review literature on people experiencing homelessness. The earlier review focused on the literature on intermediate care “generically” and found evidence in relation to older people and patients with heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), stroke or cognitive impairment. The omission of homelessness specific literature may reflect the fact that specialist intermediate care services designed specifically for people who are homeless are a relatively recent development in the UK. In 2013, investment by the Department of Health stimulated the growth of 52 new or expanded homeless intermediate care (hospital discharge) schemes and empirical research on these is emerging.

The paper begins with an overview of these recent developments in intermediate care for people who are homeless. We then outline the search strategy and the methods used to synthesise the literature on homelessness, before discussing how this additional evidence “speaks” to the conceptual framework for intermediate care proposed by Pearson et al. (2013, 2015). In the final section, we draw out the implications for service development and future research, and also make recommendations about possible refinements to the original conceptual framework. This review is reported in accordance with the RAMESES publication standards for realist reviews (Wong, Greenhalgh, Westhorp, Buckingham, & Pawson, 2013).

2 INTERMEDIATE CARE AND HOMELESSNESS

In the United Kingdom (UK) from 2001 onwards, intermediate care has been a way of preventing admission to hospital and supporting patients who are ready to leave hospital yet require further support at home. Considerable variation in the design, definition and configuration of intermediate care services has been permitted at local levels. According to the Department of Health (2009), intermediate care is a function rather than a discrete service, so it can incorporate a wide range of different services, depending on the local context of needs and the facilities available. The primary stated objective of intermediate care is to support “Anyone with a health related need through periods of transition” (Department of Health, 2009 p10). While intermediate care was designed originally to meet the needs of older people, policy guidance suggests that no one should be excluded on the basis of age, or ethnic or cultural group, and that people who are homeless should be eligible for this service (Department of Health, 2009 p4).

Long-term homelessness is characterised by “tri-morbidity”, the combination of mental ill-health, physical ill-health, and drug and alcohol misuse (Hewett, Halligan, & Boyce, 2012). People who are homeless experience chronic illnesses and long-term health conditions similar to or higher than people 15–20 years older who are not homeless (Ku et al., 2014). The Department of Health (2010) records that homeless people in England attend Accident and Emergency (A&E) departments five times as often as those who are not homeless, are admitted to hospital three times as often, and stay in hospital three times as long. This results in unscheduled care costs that are estimated to be eight times higher than for patients who are housed.

- Housing-led Schemes: These focus primarily on securing accommodation for people who are homeless on discharge from hospital. They are usually staffed by “Housing Link Workers” (ideally co-located at the hospital) possessing specialist knowledge of housing legislation and local housing options. Staffing roles include addressing broader health and well-being outcomes by means of advocating for and supporting people who are homeless to engage with the full range of local primary care, mental health, drug and alcohol and social care services.

- Clinically led Schemes: These are usually GP- or nurse-led and involve “in reach” (ward rounds) with a weekly multidisciplinary team meeting. They provide advocacy and support and have a dual aim of improving the quality of hospital care for people who are homeless, while reducing delayed or premature discharges. Housing workers often seconded from the voluntary sector and “peer navigators” (formerly homeless people) may work as part of the team to address wider housing and support needs. These schemes are often referred to as “Pathway Discharge Teams” in acknowledgement of the Pathway Charity that pioneered this way of working (Hewett et al., 2012).

With the exception of the inner-London schemes that cater to much higher numbers of people who are homeless, most HHDF schemes are small in scale, comprising 1–3 staff. All provide short-term transitional support. However, the length of time that service users can be supported varies considerably. Some schemes provide a brief intervention to organise the discharge itself, while others provide up to 3 months of intensive resettlement support. Others have access to earmarked “discharge beds” in local homeless hostels, while yet others provide follow-up support in the community or back on the street if it has not been possible to arrange accommodation.

The HHDF also funded a small number of capital investment schemes targeted at developing new residential (“medical respite”) intermediate care facilities. Medical respite is an American term for recuperative care which is targeted at people who are too sick to be out on the street or to stay in a traditional shelter, but who are not sick enough to warrant inpatient hospitalisation (Doran, Ragins, Gross, & Zerger, 2013; Doran, Ragins, Iacomacci, et al., 2013).

3 RATIONALE FOR THE REVIEW AND THE USE OF REALIST SYNTHESIS

There is mounting evidence about the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of intermediate care for people who are homeless both in the UK and internationally. Time limited care co-ordination interventions that link people who are homeless with sources of ongoing support during critical transition points have been shown in randomised controlled trials to have an enduring positive impact on a range of outcomes such as reducing rehospitalisation (Sadowski, Kee, Vanderweele, & Buchanan, 2009; Tomita & Herman, 2012) and improved quality of life (Hewett et al., 2016). A systematic review of “medical respite” found that it can result in improved health and housing outcomes for service users who are homeless, as well as reductions in hospitalisations and hospital readmissions (Doran, Ragins, Gross, & Zerger, 2013; Doran, Ragins, Iacomacci, et al., 2013). Studies consistently show homeless intermediate care schemes to be cost-effective or cost neutral (Hendry, 2009; Hex and Lowson, 2014a; White, 2011).

It is therefore generally accepted as “good practice” to make some form of specialist provision for the discharge of homeless people from hospital (Dorney-Smith, Hewett, Khan, & Smith, 2016). However, less is known about how to implement such schemes in particular local contexts that may differ in important ways from these original effectiveness studies (Pearson et al., 2015). For example, a scheme which works well in a small suburban hospital may be ineffective if replicated in a large inner-city hospital. Indeed, it is argued that working towards a “standardised model” of intermediate care is undesirable because different areas will have different levels of homelessness and different resources (Housing Learning and Improvement Network, 2009). As the Department of Health (2009) points out, “Intermediate care should provide the function of linking and filling the gaps in the local network” (p10) leading to what Medcalf and Russell (2014) term “independent local pathways of care”. This review is designed to assist service planners in the design and delivery of these independent pathways of care.

4 METHODS

Realist synthesis is an increasingly popular approach in reviewing and synthesising evidence for a range of complex interventions in health and social care services (Pawson & Tilley, 2008; Reeves, 2015). Central to the realist method is the identification and refinement of propositions about how a programme is supposed to achieve its intended outcomes, known as “programme theories”. Programme theory is operationalised as ideas about (i) what works and why; (ii) how to remedy any identified deficiency; and (iii) how the remedy itself may be undermined (Pearson et al., 2015).

4.1 Scoping the literature

To provide an evidence-informed “road map” of the complex set of factors that decision-makers should consider to make [a service] as effective as possible in any given local context. It can also be used as a diagnostic checklist to highlight weaker areas of existing provision… [and] can also inform the focus of future research.

(Pearson et al., 2015, p14)

- (Programme Theory 1): The place of care and timing of transition to it is decided in consultation with service users, based on the pre-arranged objectives of care and the location that is most likely to enable the service user to reach these objectives;

- (Programme Theory 2): Health and social care professionals foster the self-care skills of service users and shape the environment so as to re-enable service users;

- (Programme Theory 3): Health and social care professionals work in an integrated fashion with each other and carers (Pearson et al., 2015 p7).

In undertaking this review, we applied the same methods and search strategy as outlined by Pearson et al. (2015), but extended the scope of the search to include “homelessness”. While Pearson's search strategy used what they believed to be a comprehensive list of phrases relating to intermediate care, we extended the scope of this search to encompass [‘medical respite’] and [‘homelessness AND ‘hospital discharge’ (schemes)] and [‘homelessness AND ‘delayed discharge’.] This is because the term intermediate care is not widely or consistently used in the homelessness sector. The search terms used are shown in Figure 1.

4.2 Searching processes

Electronic searches were carried out for peer-reviewed articles published in English from 2000 to 2016 in the Medline, Medline in Process, Embase, Social Policy and Practice, HMIC, British Nursing Index, The Cochrane Library, CINAHL and Assia. We searched the “grey” literature through relevant websites (e.g. Department of Health; Homeless Link), as well as through the Internet using the Google search engine. We also contacted over 52 intermediate care services for homeless people in England seeking copies of any local evaluations and project reports.

4.3 Selection and appraisal of documents

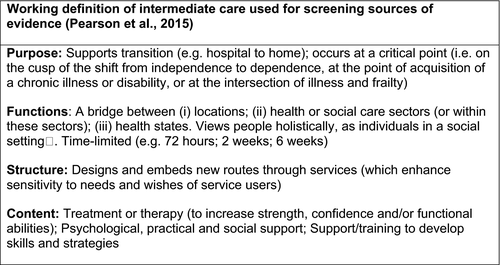

Intermediate care is a complex term that can encompass a wide range of different service configurations and functions. In selecting material for inclusion in the review, Pearson et al. (2013) helpfully distinguish between conventional “hand-overs” of care between providers and interventions that have been specifically designed to support service users’ transitions (p26). The inclusion criteria for this present review was that articles and reports should describe specific interventions to support homeless service users in transition and that the intervention should encompass most of the key characteristics of intermediate care (see Figure 2). A small number of additional articles was included which considered homeless health or hospital discharge more generally, but only where they raised issues about the need for intermediate care (see e.g. Medcalf & Russell, 2014; Parker-Radford, 2015).

Each source was read by at least two members of the research team. Papers were assessed based on the same realist “quality” criteria utilised by Pearson et al. (2015). This makes distinctions between those that are “conceptually rich” (with well-grounded and clearly elucidated theories, ideas and concepts), “thick” (a rich description of a programme, but without explicit reference to theory underpinning it) or “thin” (weaker description of a programme, where discerning a programme theory would be problematic).

4.4 Data extraction, analysis and synthesis process

The literature was synthesised with regard to how it addressed Pearson et al.'s (2015) conceptual framework. When reviewing the literature, we sought to identify programme theories that were both explicitly argued and those that were tacit or implied, making it clear which was the case. A data extraction pro forma was designed to allow the evidence to be carefully mapped against each of the three programme theories. This included space for identification of any new programme theories. The final stage of the synthesis was to take the evidence as a whole and to reflect on the overall utility of Pearson et al.'s (2015) conceptual framework, highlighting where any changes or refinements could be made.

5 RESULTS

The searches yielded 43 references of which 25 met the inclusion criteria. Additional hand-searching revealed nine further articles. Internet searching and direct contacts with intermediate care projects yielded 13 reports. These were mostly project reports and/or small-scale external evaluations. In total, 47 reports and articles were included in the synthesis.

5.1 Document characteristics

Table 1 (online resource) summarises the articles and reports (n = 47) that were included in the review, the methods they used, their “richness rating” and to which programme theories they aligned. Most of the literature fell into the “thick” category, with few papers including a theoretical perspective. Most of the empirical evidence was from the USA which focused on medical respite. The UK evidence comprised mainly local grey literature reports and was focused mainly on the hospital discharge schemes that had been set-up with the HHDF funding.

| Authors [country] | Data collection | Type | No. of participants | PT1 | PT2 | PT3 | Notes (e.g. significantly refines or surfaces new programme theory) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conceptually rich | |||||||

| Herman et al. (2011) [USA] & Tomita and Herman (2012) [USA] | Randomised control trial | CL | 150 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | New PT 4: Health, housing and social care professionals proactively manage continuity |

| Medcalf and Russell (2014) [UK] | Review of homeless health initiatives | CL | N/A | ✓ | Note on PT3: Conceptualises IC integration within broader homeless health pathways | ||

| Whiteford and Simpson (2015b) [UK] | Exploratory case analysis | CL | 18 | ✓ | Refine PT3: Knot-working identified as useful theoretical concept for understanding process of integration | ||

| Thick | |||||||

| Bauer et al. (2012) [US] | Retrospective study | MR | 860 | ✓ | ✓ | Refines PT1: Draws attention to need for women-only spaces | |

| Charles et al. (2015) [UK] | External evaluation | HL | 104 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Doran, Ragins, Gross, & Zerger (2013) and Doran, Ragins, Iacomacci, et al. (2013) | Systematic review | MR | 13 (articles) | ○ | ✓ | Note on PT2: Only one scheme listed access to physiotherapy | |

| Dorney-Smith (2011) [UK] | Economic evaluation | CL | 34 | ✓ | ✓ |

Refines PT1: Work is needed to establish engagement before consultation. Refines PT3: Advocacy is key where no agency wants to take responsibility. |

|

|

Dorney-Smith and Hewett (2016) [UK] Dorney-Smith, Hewitt and Burridge (2016) [UK] |

Feasibility study | MR | 53 | ✓ | ○ | ✓ | Note on PT2: Highlights long-term care needs often not being met. Refine PT1: Highlights potential of Psychologically Informed Environments (PIE) |

| Dorney-Smith, Hewett, Khan, et al. (2016) [UK] | Project report | CL | N/A | ✓ | ○ | ✓ | Note on PT2: A recent development within Pathway Teams is to include access to occupational therapy |

| Drury (2008) [USA] | Participant observation | HL | 60 | ✓ | ✓ | Refines PT3: Advocacy is key where no agency wants to take responsibility. | |

| Gillespie (2016) [UK] | Project report | HL | N/A | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Hendry (2009) [UK] | Economic evaluation | MR | 34 | ✓ | ✓ | Refines PT1: Work is needed to establish engagement before consultation with service users can take place. | |

| Hewett et al. (2012) [UK] & Halligan and Hewett (2011) [UK] | Descriptive case study | CL | N/A | ✓ | ○ | ✓ |

Refine PT3: Advocacy is key where no agency wants to take responsibility. Note on PT2: Highlights difficulties engaging adult social care—potentially accounting for why reablement overlooked. |

| Hochron and Brown (2013) [US] | Exploratory case analysis | CL | N/A | ✓ | |||

| Homeless Link (2015) & Albanese et al. (2016) [UK] | External evaluation of HHDF programme | All | 52 | ✓ | ○ | ✓ | Note on PT2: Highlights difficulties engaging adult social care—potentially accounting for why reablement overlooked. |

| Housing LIN & DH (2009) [UK] | Case studies x3 | HL & CL | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Lane (2005) [UK] | Feasibility study & literature review | MR | ✓ | ○ | ✓ | Note on PT2 raises issues around accessibility to physical rehabilitation. | |

| Lewis (2015) [UK] | External evaluation | HL | 10 | ✓ | ○ | ✓ | Note on PT2: Highlights difficulties engaging adult social care—potentially accounting for why reablement overlooked. |

| Lowson and Hex (2014a,b) [UK] & Lephard (2015) [UK] | External economic evaluation & project report | CL + MR | 39+ | ✓ | ○ | ✓ | Note on PT2: Highlights how resettlement can encompasses aspects of reablement |

| O'Carroll et al. (2006) [IRE] | Feasibility study | MR | N/A | ✓ | ○ | ✓ | Note PT2: Notes many hostels exclude people with mobility issues |

| Parker-Radford (2015) [UK] | Policy review & survey | 184 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Advocates transition of care approach | |

| Sadowski et al. (2009) [US] | RCT | SW + MR | 407 | ✓ | ○ | ✓ | Note on PT2: Records an improvement in physical functioning from baseline for both intervention and control groups |

| Van Laere et al. (2009) [Holland] | Statistical case study | MR | 629 | ○ | ✓ | Note PT2: Notes that MR providing palliative care | |

| Whiteford and Simpson (2015a) [UK] | Exploratory case analysis | CL | 18 | ✓ | ○ | ✓ | Note on PT2: Describes lack of access to physical rehabilitation/reablement services |

| Thin | |||||||

| Buchanan, Doblin, Sai, and Garcia (2006) [US] | Cohort study | MR | 225 | ○ | Note PT3: Skilled nursing not provided, highlights role of “volunteer health providers” | ||

| Danahay (2014) [UK] | Project report | HL | N/A | ✓ | |||

| Doran, Ragins, Gross, & Zerger (2013) and Doran, Ragins, Iacomacci, et al. (2013) [USA] | Chart review | MR | 113 | ✓ | |||

| Doran et al. (2015) [USA] | Action research | MR | ✓ | ||||

| Forchuk et al. (2008) [Canada] | RCT | HL | 14 | ○ | Refine PT3: Housing advocacy plus fast track income support seen as main mechanism | ||

| Gundlapalli et al. (2005) [US] | Descriptive case analysis | MR | N/A | ○ | Note PT1: Describes eligibility criteria linked to a range of MR provision in one county—consulting with service users not mentioned | ||

| Hewett et al. (2016) [UK] | Randomised control trial | CL | 414 | Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness study | |||

| H3 (2015) [UK] | Project report | HL | N/A | ✓ | |||

| Kertesz et al. (2009) [US] | Retrospective cohort study | MR | 743 | ✓ | |||

| Lamb and Joels (2014) [UK] | Case study | CL | N/A | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Rae and Rees (2015) [UK] | Phenomenological | 14 | ○ | ○ | Makes case for IC, focusing on importance of engagement and need for improved co-ordination | ||

| Podymow, Turnbull, Tadic, et al. (2006) | Cohort study | MR | 140 | ✓ | Note on PT2: One of few studies to list availability of physiotherapy on consultation | ||

| Redman (2010) [UK] | Project report | CL | N/A | ✓ | ○ | ✓ | Note on PT2: Highlights difficulties in meeting “physical needs” |

| SERI Insight (2014) [UK] & Housing LIN (94) (2014) [UK] | External evaluation | HL | Not given | ✓ | |||

| Shelter and Coastline Housing (2016) [UK] | Project report | HL | N/A | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Wade (2014) [UK] | External evaluation | HL | 8 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| White (2011) [UK] | External economic evaluation | HL | N/A | Provides evidence on cost-effectiveness using HES data | |||

| National Health Care for the Homeless Council (2008) [US] | Policy and practice review |

MR HL |

N/A | ✓ | ✓ | ||

- ✓, PT1: Supports/Refines Programme Theory 1: The place of care and the timing of transition to it is decided in consultation with the service user. PT2: Supports/Refines Programme Theory 2: Health and social care professionals foster the self-care skills of service users and shape the environment so as to “re-enable” service users. PT3: Supports/Refines Programme Theory 3: Health and social care professionals work in an integrated fashion with each other and carers. ○, Links to an explanatory note.

- Typologies: CL, Clinically led (multidisciplinary case management); HW, Housing Link Worker or Housing led (case management); SW, Social Work led (multidisciplinary case management); MR, Medical Respite (residential).

- All studies relate to homeless service users unless stated otherwise.

5.2 Main findings

5.2.1 Programme Theory One: The place of care and timing of transition to it are decided in consultation with the service user

The literature on homeless intermediate care confirms the central importance of consulting with service users about all aspects of their care and support. In an early feasibility study, Lane (2005) noted that a particular advantage of intermediate care was its focus on person-centred care rather than disease management, and that this could benefit people experiencing homelessness, who are often familiar with and respond well to individually tailored care, as in supported housing. Poor outcomes, such as “self-discharge”, are a significant problem where there is a failure to tailor care and support to the specific needs of people experiencing homelessness (Albanese, Hurcome, & Mathie, 2016; Bauer, Moughaian, Viloria, & Schneidermann, 2012; Dorney-Smith & Hewett, 2016; Hewett et al., 2012; Doran, Ragins, Iacomacci, et al., 2013; Medcalf & Russell, 2014).

5.3 Engagement as a distinct mechanism

A key feature of this [intermediate care] model has been the high level of engagement work undertaken… Up to one month of engagement work has been allowed before quitting to accommodate for the suspicion and distrust that often presents in these clients

(2011, p1196)

Tomita and Herman (2012) carried out an RCT which evidenced reduced hospital readmission rates and other positive outcomes for 150 homeless psychiatric patients receiving a care co-ordination intervention (compared to usual care). It was suggested that the relationship with the social services worker may be as equally an important mechanism in delivering these positive results as securing housing tenure and stability.

5.4 Tackling stigma and discrimination

Pearson et al.'s (2015) review highlights the training of staff in the specific skills needed to deliver person-centred care as an important mechanism in the delivery of successful intermediate care. However, in homeless intermediate care, “cultural distance” emerges as a complicating factor. Drury (2008), for example, describes how the daily lives of healthcare providers and homeless people are so different that they may become cultural strangers, fearfully avoiding contact with each other. Cultural distance often creates the “gaps” which specialist intermediate care is then expected to fill. In their study of continuity post hospital discharge, Whiteford and Simpson (2015a) for example, describe how some community nurses will not provide care inside hostels because they are perceived as “dangerous places”.

At times [the homeless intermediate care team] observes situations that will be familiar in our current climate—premature discharges, low thresholds being employed for bad behaviour (with no management techniques being tried or employed), and inexperienced staff affecting the overall quality of discharges.

(Dorney-Smith, Hewett, Khan, et al., 2016, p221)

A visit from an empathetic team, dedicated to the care of homeless patients in the hospital can transform this [poor experience]. The simple act of visiting the patient demonstrates that the hospital is acknowledging their particular needs, someone is observing how they are treated, they are not alone.

(Halligan & Hewett, 2011 p2)

While there is an understanding of the holistic perspective for elderly people, the attitude for complex homelessness cases… was often reported to be “They walked in here - why can't they walk out.”

(Housing Lin, 2009)

5.5 Place of care

The strongest correlate of hospital readmission among homeless people is discharge location (Kelly et al., 2013). Kertesz et al. (2009) showed discharge to a medical respite facility was associated with significantly lower odds of readmission than discharge to “own care” (including homeless shelters). Discharge to supportive housing has similar benefits (Sadowski et al., 2009).

In [Town A], the discharge scheme had access to short stay accommodation… In [Town B] there was a lack of interim accommodation and this often resulted in clients being referred to “bed and breakfast.”

(Housing LIN, 2014 p6)

Having a specialist [homeless worker] does not eradicate delayed discharge if appropriate community care is not available. However, it does tend to highlight where the gaps exist… Wet houses [hostels which permit alcohol to be consumed] tend to be available for people who are fairly independent but finding placements for people who continue to drink and have disabilities is much harder

(Housing Learning and Improvement Network, 2009 p16)

The notion that intermediate care might itself fill some of these gaps raises questions about scope and remit and how far this should extend into the territory of longer term care. According to Van Laere, De Wit, and Klazinga (2009), the high mortality rate among users of a Dutch medical respite scheme might be explained by the fact that the homeless population in Amsterdam most commonly comprises people with mental health challenges and long-term opiate users and alcoholics who are not able to live independently and depend on fragmented services. Many intermediate care schemes for people experiencing homelessness currently provide palliative care to compensate for the lack of provision elsewhere (Hendry, 2009; Van Laere et al., 2009; Whiteford & Simpson, 2015a).

5.6 Generic or specialist?

It is suggested that mainstream intermediate care facilities do not currently meet the needs of people who are homeless (Dorney-Smith, Hewett, & Burridge, 2016). The argument for “specialist” provision stems in large part from the challenges of co-housing people with different challenges and vulnerabilities (Lephard, 2015). For example, Lane (2005) charts the advantages and disadvantages of admitting people who use substances and are experiencing homelessness to mainstream intermediate care. On the one hand, it is considered that when someone is in recovery, they should not be exposed to the hostel environments in which drug and alcohol use is commonplace. On the other hand, it is recognised that people who use substances may have ways of being that are problematised by health providers and other uses of intermediate care services (Lane 2015).

Rather than being understood in the context of patient choice and the need for person-centred care planning, debates around “place of care” may be conflated with potentially discriminatory assumptions about the characteristics of different user groups. For example, Lane (2005) reports how some GPs and hostel managers he interviewed expressed concerns that “homeless people” would not mix well with other users of intermediate care who “tend to be elderly and extremely fragile both emotionally and physically” (p44), thus overlooking the potential for complex and unique behaviours related to a variety of life chances and conditions (e.g. dementia).

5.7 Safe spaces for women

A study of early exit from medical respite reported that “respite structure” (rules and regulations) could make some service users feel unsafe, and may account for why up to a third of people leave medical respite earlier than planned (Bauer et al., 2012). Women in this study were significantly more likely to leave respite before discharge completion than men. According to Bauer et al. (2012) gender-specific treatment models or women-only spaces could enhance safety and consequently retention outcomes.

5.7.1 Programme Theory Two: Professionals foster the self-care skills of service users and shape the environment so as to re-enable them

One of the key objectives of intermediate care is that people should not be admitted straight from hospital to long-term care without the opportunity for “reablement”, “recuperation” and “rehabilitation” (Department of Health, 2009). Reablement aims to support people to relearn the skills required to keep them safe and independent at home (Social Care Institute of Excellence, 2012). Importantly, while some local intermediate care services are integrated in England, physical rehabilitation tends to fall within the domain of the National Health Service (NHS), while recuperation (in a residential care home) and reablement fall under the banner of local authorities with social service responsibilities. While healthcare is free in England, social care is means tested and potentially subject to a financial charge. However, because recuperation and reablement are badged as intermediate care, they are usually provided free of charge for a period of up to 6 weeks. The optimum timeframe for intermediate care is considered to be between 2 and 8 weeks.

5.8 Reablement and physical rehabilitation needs

A feasibility study reviewed the caseload of a specialist homeless primary healthcare team in Ireland to assess the need for a specialist homeless intermediate care centre (O'Carroll, O'Reilly, Corbett, & Quinn, 2006). It found that 15% of homeless people on the caseload had mobility and disability challenges attributable to healthcare needs such as stroke, hip replacement, fracture or amputation.

In the literature on homeless intermediate care, “re-enablement” or “reablement” were not mentioned. Many studies reported difficulties collaborating with adult social care which may indicate that local authority reablement services are not easily accessible to people who are homeless (Dorney-Smith & Hewett, 2016; Hewett, Halligan and Boyce, 2012; Homeless Link, 2015; Lewis, 2014; Whiteford & Simpson, 2015a).

Just because you are homeless does not mean that you haven't got rehabilitation needs. We sometimes struggle to get patients [into rehabilitation] not because they are homeless but because of their age. Those kinds of services don't exist for patients under 55.

(View of one case manager quoted in Whiteford & Simpson, 2015a, p130)

Indeed, there is a recognised need for improved disability access in many UK homeless hostels (Dorney-Smith & Hewett, 2016).

5.9 “Reablement” environments

Mainstream residential intermediate care facilities in care homes or in hospitals often provide access to specially adapted environments, such as a “training kitchen”, in which people can practice the activities of daily living. A complaint arising from service users in one (specialist homeless) hostel-based intermediate care facility was boredom due to the lack of any kind of structured daily activity (Hendry, 2009). More recently, Pathway teams in London have employed occupational therapists to address this risk by promoting meaningful activity (Dorney-Smith, Hewett, Khan, et al., 2016).

5.10 Recovery

There is emerging consensus in the intermediate care literature specific to people experiencing homelessness that to stop the “revolving door” of hospital readmissions, support needs to extend beyond the discharge process itself, and into the community either by means of a residential “step down” facility or “floating support” arrangement (Charles et al., 2015; Dorney-Smith & Hewett, 2016; Gillespie, 2016). However, what is less clear is the ideal timeframe for such arrangements which may be termed intermediate care.

It is important to recognise that this is a ‘long game’ for many homeless clients …The starting point is about finding a way to get clients’ to believe they have something to live for which is why the building of relationships is so important… But progress from this stage might be quite slow. One systematic review suggested that even 24 months may not be long enough to generate sustainable change.

(p1197)

5.11 Resettlement

It gives people the opportunity to make real life changing decisions, and to have a real go at their lives, improving their life chances and quality of life as well as improving independence [with] daily living tasks.

(2014, p37)

In Pearson et al.'s (2015 p9) review, it is noted that one drawback with (mainstream) intermediate care is that it has tended to prioritise a desire for service users to attain certain functional goals within a specified time period over service users’ self-knowledge and desire to reach a wider set of goals over longer, less clearly defined time periods.

5.11.1 Programme Theory Three: Health and social care professionals work together in an integrated fashion with each other and carers

Housing as the “third pillar” of intermediate care

[Housing Link Workers] applied their knowledge of local authority [housing] eligibility criteria… This was knowledge that most hospital workers said that they did not have… which meant that, before [the implementation of the scheme] they had struggled with finding accommodation for homeless patients.

(Charles, Hobson, Hardwick, et al., 2015, p33)

One report of a “Housing Link Worker” scheme describes extending its remit beyond “homeless people” so that support could additionally be provided to older people who were being delayed in hospital due to “housing issues” (White, 2011).

5.12 Multidisciplinary team skill mix

An early evaluation of the HHDF concluded that those schemes taking a multidisciplinary team approach were more effective in delivering improved health and housing outcomes than those which provided access to housing in isolation (Albanese et al., 2016; Homeless Link, 2015). Without the benefit of a nursing post, some of the housing link worker projects described difficulties in engaging with what they described as the “medical model” (SERI, 2014). A nurse link worker role is mainly focused on case management rather than the delivery of clinical interventions (Dorney-Smith & Hewett, 2016).

The “skill mix” also appeared indicative of different “occupational lenses” or types and levels of comprehensiveness around how homelessness might be addressed. While the focus of the Housing Link Worker schemes was often on housing and benefits advice with “referrals on” to primary care and other agencies, Hendry (2009) describes how staff in one medical respite scheme provided a full assessment under one roof, including a full screen blood test, screening for sexually transmitted diseases, medication compliance work, pre-detox work, smoking cessation, mental health, social services, occupational therapy referrals, benefits advice and chiropody.

5.13 Involving carers and family members

In none of the material reviewed was there explicit reference to family members and carers being involved in discharge and intermediate care support planning. However, there was an account of one discharge scheme which focused specifically on linking people who were experiencing homelessness back to their country of origin or their home town where they may have a “local connection” and therefore a better chance of securing housing and social care support (Lewis, 2014).

5.14 Mechanisms for integrating services

For many of the HHDF projects, integration into the hospital setting was described as challenging (Homeless Link, 2015). Formal protocols were important, but the main problem was sustaining them (Housing Learning and Improvement Network, 2009). Successful ways of doing this and raising awareness about the schemes more generally included having the scheme championed by senior hospital staff and actively promoting the scheme through posters, leaflets and contact cards (Albanese et al., 2016 p10). Co-location and being “a face” on the ward was thought to help ensure the flow of referrals and ease of communication (Charles et al., 2015; Housing Learning and Improvement Network, 2014). Participating in ward rounds, attendance at weekly hospital staff meetings to discuss patient discharge planning, and running reflective practice and training sessions for hospital staff on the subject of homelessness were also considered helpful.

They sit alongside the patient in the middle and they co-ordinate all those links out to the other services… a bit like a spider diagram… and without them being there co-ordinating that, none of those links happen

(quoted in Charles et al., 2015 p26)

5.15 Advocacy as an additional key mechanism

Existing community services… defend their budgets by rigidly restricting access to a defined ‘local’ population—this renders care co-ordination particularly challenging for homeless people, who often have weak or no ties to any locality and lack documentary proof of any entitlements.

(Dorney-Smith & Hewett, 2016 p11)

6 DISCUSSION

6.1 Summary of findings

The additional evidence presented above does then broadly support the validity or usefulness of Pearson et al.'s (2015) conceptual framework for understanding “what works and why” in intermediate care. This is with regard to three key programme theories: the importance of consulting with service users (PT1), working in ways which are enabling (PT2) and ensuring integrated professional working (PT3). However, it might be suggested that these three “programme theories” are likely to be implicated in the successful delivery of many other health and social care services. Herein, lies a potential limitation of the current framework in that it may not answer some of the more complex or nuanced questions relating specifically to the development of intermediate care services.

The first challenging question to emerge from this review is how to maintain the integrity of intermediate care as a “time limited” intervention. This issue arises where there is a need to encompass multiple and overlapping rehabilitative and resettlement goals which may require housing solutions underpinned by much longer term or continuing health and social care support. Indeed, the issue of “timeframe” and scope is relevant to commissioners of intermediate care for both older people and people who are homeless. It is acknowledged that the rehabilitation of older people has sometimes fallen short because it has often prioritised short-term reablement goals linked to “physical functioning” over and above those for inclusion and citizenship. Meanwhile, intermediate care for people who are homeless has reversed the “occupational lens” prioritising longer term resettlement and recovery outcomes over and above those for reablement. How to encompass these different needs and vulnerabilities under a single service banner is a significant additional challenge, with the danger that “specialist” provision starts to confirm cultural distance (e.g. “elderly people” are quiet and frail, “homeless people” are challenging and disruptive).

These issues are compounded in times of austerity, when the integrity of intermediate care is further compromised by the need not just to “fill the gaps” in local provision but on occasions to substitute for the widespread loss of longer term support services. As Backer et al. (2007) suggest, discharge planning and intermediate care will have little impact unless housing and other services are available. It is recognised that this poses perhaps the most serious threat to the viability of intermediate care as a service organisation and delivery construct. If the boundaries with longer term care start to blur, then intermediate care risks quickly becoming “blocked” (Dorney-Smith, Hewett, Khan, et al., 2016; Poymow et al. 2006).

- Phase 1: Transition to the community—focuses on engagement and relationship building—providing intensive support and assessing the resources that exist for the transition from inpatient care to community providers.

- Phase 2: Tryout—is devoted to testing and adjusting the systems of support. And assessing whether or not they are working as planned. By now community providers are assumed to have adopted primary responsibility for delivering support.

- Phase 3: Transfer of care—focuses on completing the transfer of responsibility to community resources that deliver long-term support (Herman et al., 2011 p715).

Maintaining continuity of care during critical transition periods while responsibility gradually passes to existing community supports that will remain in place after the intervention ends.

(Herman et al., 2011 p714)

In CTI, “scope” is clearly defined as being about the management of transitions rather than specific kinds of “needs” or “gaps” in existing provision. It is thus generic in that it can be applied to all client groups and can potentially be operationalised in any given local context as the aim is to “weave together” the resources and infrastructure that are already in existence. The “timeframe” for the intermediate care intervention is also determined not by any rigid “service led” criteria but by the adaptive capacity of the local context to meet the person's needs. It might be added that where CTI becomes “blocked” (i.e. there are no appropriate services to take over responsibility) then this should ring alarm bells for commissioners that there are “cracks” in local provision.

Indeed, CTI also seems to encapsulate the “how to” of what Parker-Radford (2015) terms a “transition of care approach”. This has the additional advantage of shifting the focus of the “organisational lens” from the acute sector to the management of a much wider range of transitions (e.g. “prison-to-community” and “armed forces-to-civilian”). It is therefore potentially key to continuity and seamless care as seen from the perspective of people who use services.

7 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

- (Programme Theory 1): The place of care and timing of transition to it, is decided in consultation with service users [ibid]… “Engagement work” is recognised as a distinct mechanism for underpinning these more formal consultative or collaborative care planning processes.

- (Programme Theory 2): Health, housing and social care professionals foster the self-care skills of service users and ensure that rehabilitation and recovery are encompassing of outcomes linked to both physical reablement and broader health and well-being objectives for inclusion and citizenship

- (Programme Theory 3): Health, housing and social care professionals work in an integrated fashion with each other, ensuring local advocacy support is available.

- (Programme Theory 4): Continuity of care is maintained during critical transition periods while responsibility gradually passes to existing community supports that will remain in place after the intermediate care episode ends.

7.1 Limitations

The limitations of the review are that while we have outlined our search strategy judgements have been made about the interpretations of the findings. Identifying programme theories and mechanisms from sources that are not explicitly theory driven, or do not provide adequate descriptions of the services, is also problematic. Nevertheless, using realist synthesis to build “conceptual frameworks” which can guide future intervention development about ‘what works’ for whom and in what circumstances may be an important step in complementing more traditional evidence-based approaches which often leave these questions unaddressed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT AND DISCLAIMER

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.