A review of self-rated generic quality of life instruments used among older patients receiving home care nursing

Abstract

In the last two decades, quality of life and health-related quality of life have become commonly used outcome measures in the large number of studies evaluating healthcare and home care nursing. The objective of this systematic search and review was to evaluate studies that include self-rated generic quality of life instrument used among elderly patients receiving home care nursing. Searches were conducted in Medline, Embase, PsycINFO and Cinahl for articles published between January 2005 and June 2016, with 17 studies in eight countries meeting the inclusion criteria and assessed for quality. Overall, the review shows great variations in the included studies regarding characteristics of the participants and place of origin, the generic quality of life instruments applied and their dimensions. In this review, we raise the question of whether the generic questionnaires used to measure quality of life do in fact measure what is essential for quality of life in elderly users of home care nursing. The psychological and physical dimensions of quality of life were assessed in almost all included studies, while older-specific dimensions like autonomy, control and sensation were less frequently assessed. There is reason to believe that generic quality of life instruments frequently do not capture the dimensions that are most important for elderly people with health problems in need of home care nursing.

What is known about this topic

- Healthcare for elderly people is changing and is moving from hospitals and nursing homes to home care.

- The aim of a generic instrument is to cover multiple aspects and dimensions of both health and quality of life.

- Quality of life in elderly adults should be assessed in a broad perspective focusing on health, physical, psychological and social function.

What this paper adds

- In the present review, only one study followed the recommendation of using an instrument with individual and environmental variables.

- Researchers and clinicians should use quality of life instruments that are designed specifically for seniors in need of home care nursing.

Introduction

Populations around the world are rapidly ageing (WHO, 2015). In 2010, an estimated 524 million people were aged 65 or older, which is 8% of the world's population. By 2050, this number is expected to nearly triple to about 1.5 billion, representing 16% of the world's population (National Institute on Ageing, 2011). Ageing presents both challenges and opportunities and will increase demand for acute and primary healthcare, and the need for long-term care (WHO, 2015). Due to the number of elderly people in need of support, many countries tend to move nursing care from hospitals and nursing homes to home care.

Home care can be conceived of as any care provided within the home or, more generally, refers to services enabling people to remain in their home environment. The term ‘home care’ is very differently understood across countries and sectors. The services included vary considerably among countries and even ‘home’ turns out to be an elastic term (Genet et al. 2012). In this review, home care nursing refers to care given only by authorised healthcare workers in the recipients’ private homes.

A variety of definitions of quality of life are reported in the literature, and researchers use different approaches or models to explain the concept. In fact, researchers work within different paradigms to evaluate quality of life (Wilson & Cleary 1995). The underlying reason for measuring quality of life in healthcare is to ensure that evaluations focus on the patient rather than the disease. In the last two decades, quality of life (QOL) and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) have become commonly used outcome measures in most of the studies evaluating healthcare (Haywood et al. 2005, Reeve et al. 2013). Although a meta-analysis of the relationships among quality of life, perceived health status, and the domains of mental, physical and social functioning were found to be distinct constructs (Wilson & Cleary 1995), the Short Form (36) Health Survey is named as QOL, HRQOL and Health Status in the literature (Løyland et al. 2010). As the variety of terms used is a challenge, the authors of this paper have decided to not discriminate between HRQOL and QOL.

It has been suggested that QOL in older adults should be assessed in a broad perspective focusing on health, physical, psychological and social function (Farquhar 1995, Fayers & Machin 2016). QOL in old age is influenced by experiences throughout a long life, and by more immediate conditions like sickness and accidents in later years. We currently have only modest knowledge of the interaction between such long-term and short-term patterns and dynamics. This is important when the aim is to develop more age friendly societies as recommended in a Norwegian Governmental Paper from 2016 (Hansen & Daatland 2016).

A variety of instruments are reported in the literature claiming to measure QOL in general. The aim of a generic instrument is to cover multiple aspects and dimensions of both health and QOL (Guyatt et al. 1993, Fitzpatrick et al. 2004). Different approaches and measurements have been used in assessing QOL among older adults (Wodchis et al. 2007, Yamada et al. 2015). Some measurements, such as Health Survey SF-36 and SF-12, have been used among both younger and older adults (Graessel et al. 2014, Hirani et al. 2014). Fayers and Machin (2016) emphasised that differential item functions in the latter instrument may arise. In order to perform comparative studies, we need an overview of what kinds of generic QOL instruments are utilised among elderly patients receiving home care nursing, and what dimensions of QOL they measure.

Therefore, the objective of this systematic search and review was to evaluate studies that include self-rated generic QOL instruments used among elderly patients receiving home care nursing. We have used dimensions of QOL from one generic instrument with an older-specific add on module as recommended by Power et al. (2005) to ensure the specific requirements when assessing studies of QOL in old age (Power et al. 2005, Conrad et al. 2014).

The research questions for this review are: What characterises studies on generic QOL analysed in terms of participants and designs? What characterises the quality of the included articles assessed by means of the CASP-criteria? Which QOL instruments are used?

Methods

In this paper, we used an approach defined by Grant and Booth (2009) as a ‘systematic search and review’ (pp. 95), combining elements from critical review with a comprehensive search of the literature (Grant & Booth 2009). Additionally, we evaluated the included articles according to Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). The programme has developed workshops and tools for critical appraisal covering a wide range of research. The programme has also developed checklists with criteria for quality assessment of specific research designs (CASP 2014).

Search strategy

In mid-September 2015, a systematic literature search was conducted with the assistance of a research librarian. An updated search was performed in June 2016. The first step was to formulate the research questions and facilitate the literature search by using the PICO framework (Patient problem, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome) (Schardt et al. 2007). The selected databases were: Ovid – Medline, Embase, PsycINFO and EBSCO – Cinahl, as these databases comprise home care and nursing. The following words were entered into the above-mentioned databases: ‘home care services OR home health nursing AND home care OR home based OR home health OR visiting nursing service AND quality of life OR health related quality of life AND aged OR geriatr* OR elderly OR older OR old OR octogenarian* OR senior* AND questionnaire* OR survey* OR instrument* OR index* OR structured interview* OR self report* OR self rate* OR patient reported outcome* AND data collection’.

We also performed a second systematic search in Medline and Cinahl on particular generic quality of life instruments as described by Haywood et al. (2005).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Table 1 shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria used in this review. The articles should be published in Scandinavian (Norwegian, Swedish and Danish) or English languages in peer-reviewed journals.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

Generic quality of life instruments Assessment by self-rating or structured interviews Participants ≥65 years (acceptable if mean age is presented to be ≥65 years) Published 2005–2016 Published in English or Scandinavian |

Disease specific instruments Transition between hospital and home Rated by proxy Qualitative studies Case studies Cost analysis and economic evaluation Caregivers Health personnel's perspectives Mixed groups, e.g. patients and caregivers, patients and health personnel Specific treatment, e.g. physical therapy, surgery, pharmacological treatment Rehabilitation programmes Cognitive impairment Palliative care Veterans |

Quality assessment

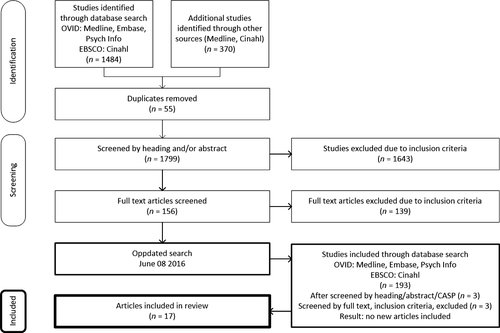

A flow chart describes the selection of studies (Figure 1). Three steps, from examination of titles, abstracts and full-text inclusion, show the process revealing the 17 papers included for full-text reading and quality appraisal. All authors were involved in the selection of articles, from the title and abstract review to the full-text examination.

We appraised each paper depending on the study design according to the CASP checklists for randomised controlled trials (RCT) and cohort studies (CASP 2014). Criteria without a possibility of a yes or no answer were not included in our review. The checklist for RCT includes the following nine criteria: (i) addressing a clearly focused issue; (ii) randomisation; (iii) blinding of participants and study personnel; (iv) congruence of groups at baseline; (v) equal treatment of included groups; (vi) principle of intention to treat by inclusion; (vii) generalisability of findings; (viii) discussion of clinically important outcomes; and (ix) consideration of study benefits. The checklist for cohort studies includes the following eleven criteria: (i) addressing a clearly focused issue; (ii) acceptable recruitment; (iii) accurate measurement of exposure; (iv) accurate measurements of outcome; (v) and (vi) confounding factors; (vii) and (viii) follow-up of subjects; (ix) reliability of findings; (x) generalisability of findings; and (xi) consideration of other evidence. Each criterion was given an equal weight (i.e., 1 point for yes and 0 point for can't tell or no) for a maximum score of 9/11 for each quality assessment per article. A top score of 9/11 for the RCT and cohort studies respectively, was considered as high methodological quality, whereas less than 8/9 points was considered as moderate quality; see Table S2. The authors were organised into pairs, and each pair of researchers first reviewed each article individually and then compared the CASP-score. In case of discrepancies or difficulties, consensus between authors was reached for each pair. We experienced no disagreement between the authors.

Standardised forms were developed to extract an overview of characteristics of the included studies and to determine what generic quality of life instruments were used among older patients receiving home care nursing, see Tables S1 and S2.

Results

After removing duplicates, the database searches resulted in 1854 citations. Only 17 articles were found to be in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). The most frequent exclusion criteria were a lack of home-based nursing, specific treatment, e.g., physical therapy, surgery, pharmacological treatment or specific diagnosis groups.

Table S1 describes the final sample of 17 included studies. They varied in terms of origin (country), aim, design, sample size, measurements used and quality of the studies (CASP-score).

Country

Eight studies were conducted in Europe: Two in the Netherlands, Germany and England; and one study in each of the following countries: Sweden and the Czech Republic. Seven studies were conducted in North America, three in the USA and one in Canada. Three of the North American articles resulted from a collaboration between researchers from USA and Canada using the same sample with different perspectives presented in each article (Zhang et al. 2006, Wodchis et al. 2007, Maxwell et al. 2009). Two studies were conducted in New Zealand.

Design

Eight studies had a cross-sectional design and were conducted as cohort studies on different aspect of QOL in various home care settings (Friedman et al. 2005, Wodchis et al. 2007, van Bilsen et al. 2008, Maxwell et al. 2009, Matlabi et al. 2011, Karlsson et al. 2013, Yamada et al. 2015). Eight studies were longitudinal, and six of these were RCTs aiming to examine the effect of different home-based care interventions like home-based telecare (Hirani et al. 2014), a home-based nursing care co-ordination programme (Marek et al. 2014), a proactive nursing health promotion intervention (Markle-Reid et al. 2006), effect of Resident Assessment Instrument in home care (Stolle et al. 2012) and restorative home care service (King et al. 2012). The other two assessed responsiveness of different QOL instruments (Zhang et al. 2006, van Leeuwen et al. 2015). Two studies were prospective RCTs, one predicting HRQOL after stroke (Graessel et al. 2014) and the other assessing the impact of a designated goal facilitating tool (Parsons et al. 2012).

Data collection

The most commonly used data collection method was self-reported questionnaires (sent by mail or handed out by a study personnel). Four of the cross-sectional studies used structural interviews face-to-face or by telephone to secure a high response rate.

Sample

The sample size of the included studies ranged from 1189 to 58 patients. Age is described by mean and standard deviation or median and range in the included studies. For us the main criterion was a reported mean >65 years or the majority of the total sample >65 years. Patients needing special service and accommodation are usually older, >80 years, compared to patients only receiving home healthcare. Women usually made up 60%–70% of the total sample in the included studies with two exceptions: One study included only women (Friedman et al. 2005), and one study on stroke patients had 60% men (Graessel et al. 2014).

Quality of the included studies

CASP scores for the cohort studies varied between 6 and 11 out of a possible score of 11, and the RCTs from 7 to 9 out of a possible score of 9 (Table S1). We decided not to exclude any of the included studies based on CASP scores because all studies were appraised to be of at least moderate quality.

QoL instruments

A total of 16 different generic QOL/HRQOL instruments were applied in the included studies (Table S2). The most frequently used instruments were SF-36/SF-12 (eight studies), EQ5D/EQ5D-3L (four studies) and Health Utilities Index mark 2 (HU12) (three studies). The number of instruments used in each study varied from five to one. However, EQ5D/EQ5D-3L, measuring general health status, is hardly ever used alone. The use of SF36/SF12 is widespread throughout the world. The other instruments were more specific regarding geographic area. EQ5D/EQ5D-3L is developed for European populations and HUI2 is only used in North America. Table S2 describes in more detail how and where the different instruments have been utilised and in which combinations. Quality of life was presented with different concepts like HRQOL (SF36), health utilities (HUI2) and perceived quality of life (PQOL).

Dimensions of quality of life

Table S2 shows that the psychological dimension of QOL was assessed in all the included studies. This dimension was represented in various forms like the mental component score in SF36, pain and discomfort, anxiety, depression and cognition. The physical domain of QOL was measured in 16 of the 17 included studies. The physical component score in SF36/SF12 was dominant, and also bodily pain, mobility and activity were categorised within the physical domain. The social domain was always assessed when the studies utilised SF36 and its social functioning score, but some also assessed domains like dignity and social participation. The environmental dimension was usually assessed by degrees of self-care. Dimensions less frequently assessed were autonomy, control and sensation.

Discussion

This review of the published literature on QOL among elderly patients receiving home care nursing included 17 studies, following exclusion and quality assessment. The included studies show great variations regarding characteristics of the participants and place of origin, generic quality of life instruments applied and their dimensions.

Most of the included studies, with sample sizes varying between 1189 to 59 participants, had a majority of female participants, which is typical for the elderly population in general (WHO, 2015). Another result was that all included studies were performed in ‘western’ parts of the world: Europe, North America and New Zealand. Healthcare systems, and thus nursing care, in the community differ considerably from country to country and have different nomenclatures and funding. The present review found that the names of the service ‘home care nursing’ differ and the service seems to be organised in different ways. Another term for home care nursing is ‘In-home medical care’, or ‘home healthcare’ or ‘formal care’. Some countries have insurance arrangements, others private payment for the service, while others cover healthcare in the community by tax refund. We assume that some countries actually lack a structured home care nursing system at all (Blais & Hayes 2015). Often, the term home healthcare is used to distinguish this service from non-medical care, custodial care, or private-duty care, which refer to assistance and services provided by persons who are not nurses, physicians or other licensed medical personnel.

The designs varied greatly. It is a challenge to perform longitudinal studies with older adults and generic instruments may prove inadequate for showing changes in QOL when the follow-up covers a longer period, e.g., from the age of 70 to the age of 80 (Noyez et al. 2011).

Four of the included studies used structured interviews to collect data. This may influence the validity of self-report, as the respondent might be more reluctant in answering sensitive questions (Kalfoss & Halvorsrud 2009). On the other hand, for data collection among older adults, including structured interviews or self-assessment, interviews have been described as the least burdensome for the participants (Bowling, 2005). Reeve et al. (2013) underlined that the patient's self-report compared with proxy assessment is the best source of information about what he or she is experiencing.

A total of 16 different generic QOL/HRQOL instruments were applied in the included studies. With such a wide range of instruments as revealed from this limited review, this makes it difficult to compare results. When an instrument like SF-36 is applied and compared between different continents (e.g., North America and Europe), the interpretations of the cultural and contextual characteristics can vary greatly. Therefore, uncritical use of generic instruments has resulted in conceptual limitations regarding how researchers present patients’ quality of life in different settings and cultures (Grov & Valeberg 2012).

The challenge is associated with the term ‘quality of life’ as it is still not clearly defined despite long research traditions within health research and healthcare the last 30 years (Fayers & Machin 2016). We address this issue briefly by referring to three different models for conceptualisation of quality of life (Lawton 1991, Wilson & Cleary 1995, Spilker & Revicki 1996). Spilker's model offers a hierarchical approach to quality of life, with overall QOL at the top, the domains of HRQOL in the middle and the disease-specific components of quality of life at the bottom. In Wilson & Cleary's model, different types of variables describing aspects of HRQOL interrelate, including an overall assessment of QOL. This model is not grounded in a specific definition of quality of life like Spilker's. Lawton (1991) proposed that QOL is composed of four sectors: behavioural competency (e.g. activities of daily living or cognition), perceived quality of life (e.g. pain and discomfort), psychological well-being (e.g. mental health and overall satisfaction with life) and objective environment (e.g. home and social network). Lawton emphasises the interaction between the individual and the environment in his conceptual model (Lawton 1991). In sum, we propose that these models address the importance of using generic QOL instruments with both individual and environmental variables. Older adults experience biological challenges with more comorbidity, sociological and psychological changes due to old age, as well as individual and environmental gains and losses (Ebersole et al., 2004).

In the present review only one study followed the recommendation of using an instrument with individual and environmental variables. WHOQOL-OLD has included older-specific facets as dimensions of quality of life: e.g., sensory abilities, autonomy and intimacy in terms of having somebody to love or be loved.

For those facing loss of family and friends, questions about intimacy might be important. Perspectives on loss and being alone should be included for patients receiving home care nursing (Hansen & Slagsvold 2015). Age-related changes in general lead older adults to assign highest mean importance to QOL factors like daily living, mobility, sensory abilities, health and home environment (Ebersole et al. 2004, Kalfoss & Halvorsrud 2009). Therefore, QOL instruments need more particular content and dimensions to cover challenges met by those in need of nursing care at home, e.g., the degree of functional, mental or cognitive impairment, frailty, ability to cope with activities of daily living and comorbidity. On the other hand, it is also proposed, especially for the older generation, that without good physical and mental health other opportunities for self-expression are of little value (Stiglitz et al. 2009).

The CASP-evaluation provided systematic insight into each paper's strength and limitations, but some of the CASP-manual's criteria proved difficult to use. The appraisal criteria were originally developed from the viewpoint of practice, and not as a tool for finding the best evidence in a systematic literature study (MacDermid et al. 2009). The questions in the appraisal-tools without a ‘yes’, ‘can't tell’ or ‘no’ alternatives were difficult to classify and not accounted for in Table S2 (please see the Results section).

Being nine co-authors working together in pairs on the CASP-evaluation proved to be a challenge. Each member could contribute with different expertise and knowledge regarding research designs and methods. There is no agreement about the number of assessors for reviewing the content and quality of studies to be included in a systematic review. However, studies show that an increase in the number of evaluators increases the possibility of assessment bias (Pölkki et al. 2014). We tried to avoid this by giving senior researchers (one in each pair) the responsibility of making final decisions.

This review is concerned about the way researchers compare organisational services, as well as the description of ‘home care nursing’ as a term. This aspect proved to be problematic when we performed the search in different databases using different MeSH terms for ‘home care nursing’: from ‘home care services’ in Medline to ‘home healthcare’ in CINAHL. This problem was solved when articles were assessed for eligibility in the screening process (Figure 1).

We have performed a systematic search and review with transparent descriptions of the selection process for the included articles. However, we acknowledge that a complete overview is not attainable, despite our approaches.

Conclusion

In this review, we raise the question of whether the generic questionnaires used to measure QOL do in fact measure what is essential for QOL in elderly users of home care nursing. There is reason to believe that generic QOL instruments often do not capture the dimensions that are most important for elderly people with health problems. The phenomenon of variable and numerous assessment instruments used in QOL research is not new to the audience. Also that unvalidated instruments are used, self-created by teams and only used once. We therefore recommend that researchers and clinicians start to use validated instruments designed specifically for seniors, such as WHOQOL-OLD, because this generic instrument has included older-specific facets such as sensory abilities, autonomy and intimacy. This makes it important to highlight the methods used to develop each generic QOL instrument and the contents of measurement because the interpretations of the cultural and contextual characteristics vary greatly. These facets are particularly important for QOL among elderly people in need of home care nursing.