Cancer screening behaviours among South Asian immigrants in the UK, US and Canada: a scoping study

Abstract

South Asian (SA) immigrants settled in the United Kingdom (UK) and North America [United States (US) and Canada] have low screening rates for breast, cervical and colorectal cancers. Incidence rates of these cancers increase among SA immigrants after migration, becoming similar to rates in non-Asian native populations. However, there are disparities in cancer screening, with low cancer screening uptake in this population. We conducted a scoping study using Arksey & O'Malley's framework to examine cancer screening literature on SA immigrants residing in the UK, US and Canada. Eight electronic databases, key journals and reference lists were searched for English language studies and reports. Of 1465 identified references, 70 studies from 1994 to November 2014 were included: 63% on breast or cervical cancer screening or both; 10% examined colorectal cancer screening only; 16% explored health promotion/service provision; 8% studied breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening; and 3% examined breast and colorectal cancer screening. A thematic analysis uncovered four dominant themes: (i) beliefs and attitudes towards cancer and screening included centrality of family, holistic healthcare, fatalism, screening as unnecessary and emotion-laden perceptions; (ii) lack of knowledge of cancer and screening related to not having heard about cancer and its causes, or lack of awareness of screening, its rationale and/or how to access services; (iii) barriers to access including individual and structural barriers; and (iv) gender differences in screening uptake and their associated factors. Findings offer insights that can be used to develop culturally sensitive interventions to minimise barriers and increase cancer screening uptake in these communities, while recognising the diversity within the SA culture. Further research is required to address the gap in colorectal cancer screening literature to more fully understand SA immigrants’ perspectives, as well as research to better understand gender-specific factors that influence screening uptake.

What is known about this topic

- Over time, South Asian immigrants who settle in western countries have similar rates of cancer incidence for breast, cervical and colorectal cancers as native-born populations. Population-based breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening is recommended for early detection. Yet, disparities in screening uptake among South Asian immigrants persist.

- An understanding of the sociocultural context influencing cancer screening uptake is needed to develop effective programmes to improve cancer screening rates among South Asian immigrants.

What this paper adds

- An examination of the sociocultural context of South Asian immigrants’ beliefs and attitudes towards cancer screening elucidated the need to consider family and holistic beliefs in the development of health-promoting messages; to increase knowledge about risk factors and cancer screening benefits; and to address health system barriers to increase screening uptake.

- Public health and cancer care practitioners should involve South Asian immigrants in the development of community-based programming to address local needs with the aim of increasing screening uptake.

- There is limited evidence about factors influencing uptake of (or participation in) colorectal cancer screening including gender-specific factors among South Asian immigrants.

Introduction

Population-based cancer screening for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer has the potential to reduce mortality and morbidity if performed as per guideline recommendations in the general average risk population (United States Preventive Services Task Force 2008, 2009, 2012). However, rates of uptake for breast, cervical or colorectal cancers among ethnic minority populations in the United Kingdom (UK), United States (US) and Canada are sub-optimal (Quan et al. 2006, Szczepura et al. 2008, Lee et al. 2010a). South Asian (SA) immigrants form a growing community in the UK, US and Canada (Statistics Canada 2008, US Census Bureau 2010, UK Census 2011). SA immigrants also represent a diverse community with ancestral origins largely from the Indian subcontinent including India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and smaller numbers from the diaspora, originating from countries such as South or East Africa and the Caribbean (Ballard 2003, Tran et al. 2005). The incidence rates of breast and colorectal cancers among SA immigrants residing in the UK and North America are comparable to those in non-Asian-born populations (Smith et al. 2003, Jain et al. 2005, Hislop et al. 2007, Hossain et al. 2008, Rastogi et al. 2008; Virk et al. 2010). Yet, disparities in cancer screening have been documented with SA immigrants having low rates of breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening (Szczepura et al. 2008, Lee et al. 2010a, Lofters et al. 2010). Thus, SA immigrants are at risk for avoidable morbidity and mortality from these cancers.

While prior reviews have examined cancer screening-related barriers among ethnic minority populations in the UK, US and Canada (Wu et al. 2005, Elkan et al. 2006, Johnson et al. 2008, Hanson et al. 2009, Alexandraki & Mooradian 2010, Sokal 2010), they have focused on studies in one country, one or two population-based cancer screening modalities (i.e. breast, cervical) or excluded SA immigrants. Barriers to cancer screening among SA immigrants include individual and structural barriers. Individual barriers to cancer screening or access to health services reflect issues not always under the control of the individual (Baron et al. 2008). The individual barriers to screening encountered by SA immigrants include lack of knowledge and access, low self-perceived risk, loss of social networks, language barriers and competing priorities of work and family (Ahmad et al. 2004, Oelke & Vollman 2007). Structural barriers include health policy, socioeconomic factors, health insurance coverage and systemic health service provision, such as usual source of care (family physician), screening service hours of operation, local access to services or transportation (Baron et al. 2008). SA immigrants identified structural barriers to cancer screening such as lack of local access (Thomas et al. 2005) and lack of physician recommendation (Somanchi et al. 2010).

To address health inequities related to low cancer screening among SA immigrants, an understanding of the sociocultural context including beliefs and attitudes, and facilitators and barriers to cancer screening in these populations is required. To this end, a scoping study utilising Arksey & O'Malley's (2005) framework was undertaken. This framework provides a structured method to develop a comprehensive understanding of current knowledge, and to identify knowledge gaps through the examination of diverse and heterogeneous literature. In this scoping study, the research question was: What are the cancer screening beliefs, attitudes and behaviours of SA immigrants residing in the UK, US and Canada? The intended outcome was a synthesis of existing knowledge about barriers and facilitators to cancer screening in these populations to inform current practice, policy and future research.

Methods

Arksey & O'Malley's (2005) framework encompasses five stages: (i) research question formulation; (ii) a comprehensive literature search and development of relevancy criteria; (iii) identification of relevant studies; (iv) charting of extracted data from included studies and reports; and (v) summarising and reporting of findings. This method is advantageous as it incorporates not only a transparent and reproducible search strategy but also enables an examination of a broad research question by the inclusion of a variety of study designs and development of study selection criterion in an iterative manner. A narrative review that employed thematic analysis was the approach used as a process to produce a simplified synthesis of included studies or reports (Mays et al. 2005). The narrative review process aims to present findings as they are reported in the literature and does not aim to transform data. This method is comprehensive, flexible and efficient because it allows different types of evidence to be used to identify main concepts related to a specific research topic that has not undergone prior review. To synthesise evidence, a thematic analysis of dominant recurring and important themes from the literature was undertaken to address the research question (Mays et al. 2005, Levac et al. 2010). The narrative review method utilising thematic analysis gives high importance to the relevance of literature and does not attempt to assess the quality of studies.

For this study, the concept of population-based cancer screening included breast, cervical and colorectal cancers. The health outcome of interest, cancer screening behaviours, encompassed: beliefs and attitudes towards cancer and screening; barriers and facilitators to cancer prevention; reasons for screening; and cancer screening uptake. The target population was SA immigrants defined as individuals who originate from the southern part of Asia or who claim a cultural ancestry or origin from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka or Nepal, and may include ethnic backgrounds from diverse ancestries, such as Hindu, Goan, Gujarati, Nepali, Sikh, Punjabi, Pakistani or Tamil (Tran et al. 2005).

A librarian was consulted for the literature review process and refinement of the search strategy, and a primary reviewer became familiar with the literature. An interdisciplinary team comprised of a public health practitioner with oncology certification and experience working with immigrant populations; a medical health professional and health services researcher; a public health researcher with a focus on immigrant communities including SAs; and an occupational therapist and clinical epidemiologist with interest in disease prevention and cross-cultural adaptation of materials and measures. All members were involved in decisions surrounding inclusion and exclusion criteria, and refinement of themes.

A literature search was initially conducted in June 2012 and was updated in November 2014. English language studies and reports were searched using the following electronic databases: Ovid MEDLINE [1946–October Week 5 2014], EMBASE [1980–2014 Week 45], PsychoINFO [1806–November Week 1 2014], CINHAL, PubMed, the Cochrane Library [Issue 11 of 12, November 2014], Scopus and System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe. Six key journal volumes and issues were searched electronically from January 2005 to November 2014 inclusively: Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention; Canadian Journal of Public Health; Cancer; Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health; Journal of Medical Screening; and Social Science and Medicine. The Web of Science was also searched using relevant studies included in the scoping study because of the potential to yield further citations (Ahmad et al. 2005, De Alba et al. 2005, Asanin and Wilson 2007, Robb et al. 2008, Szczepura et al. 2008, Glenn et al. 2009, Taskila et al. 2009, Pourat et al. 2010). Reference lists of included studies were also searched, as well as key websites of evidence-based reports, for example, Cancer Care Ontario, Public Health Agency of Canada, Ontario Women's Health Evidence-Based Report, the Council of Agencies Servicing SA in Ontario and the UK Bowel Screening Programme.

The main subject headings and key word search terms used were as follows: ‘Asian’, ‘Asian Continental Ancestry Group’, ‘Asian American or British Asian or Indian’, ‘Hindu’, ‘Bangladesh’, ‘Sri Lanka’, ‘emigrants and immigrant’, ‘illegal immigrant’, ‘migrant’, ‘refugee’, ‘cancer screening’, ‘mass screening’, ‘cancer prevention’, ‘early detection of cancer’ and ‘secondary prevention or prevention’. The explode function was used for applicable Medical Subject Headings, and truncation expanded the search for terms with unique endings. The search terms were refined for different databases. No limits were placed on years of publication to prevent restricting searches.

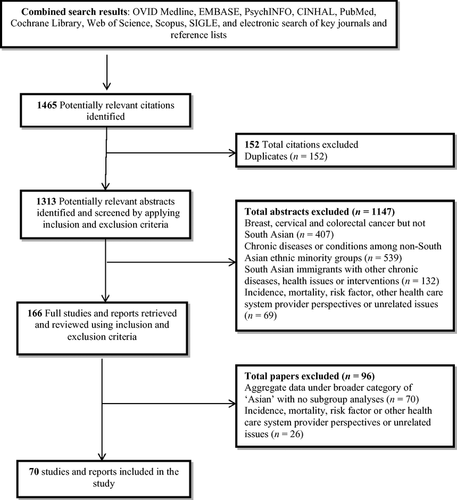

The combined searches resulted in the retrieval of a total of 1465 citations; Figure 1 presents the combined totals for the two searches. In keeping with the iterative nature of Arksey & O'Malley's (2005) framework, becoming familiar with retrieved literature enabled a determination of study selection criteria. To determine study selection criteria, retrieved studies were reviewed for any discrepancies related to terminology used to define the population or intervention. A method to eliminate studies included developing inclusion and exclusion criteria based on the research question. In a scoping study, this is done posthoc to become familiar with the available literature. The aim of applying relevancy criteria to studies was to ensure that selected studies for review focused on answering the research question (Arksey & O'Malley 2005).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria incorporated type of study, target population and type of intervention. Studies and reports were included if they: (i) employed quantitative and qualitative methods, were published in English between 1994 and 2014 and were accessible; (ii) included samples of SA immigrant men and women who resided in the UK, US and Canada; and (iii) investigated factors related to breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening services. Studies were excluded if they reported on breast, cervical and colorectal cancers, but did not include SA immigrants; discussed chronic diseases or health issues among non-SA ethnic minorities; reported on incidence, mortality, risk factors of all three cancers; centred on healthcare system providers’ perspectives or other unrelated issues; or aggregated data under a broader category of ‘Asian’ with no clear distinction of SA immigrants or subgroups. RefWorks (2.0) was used to organise and manage literature searches and retrieved citations.

An additional step was to contact practitioners and preventive healthcare providers to identify additional references, unpublished reports or to gain insight into the topic area (Arksey & O'Malley 2005). Informal contact was made with public health practitioners working in the field and key organisations such as Cancer Care Ontario for any additional unpublished reports.

The primary reviewer independently applied inclusion/exclusion criteria to all abstract citations during abstract review. If relevancy was difficult to ascertain from an abstract, the full text article was retrieved. The primary reviewer read all potential full-text papers. In the case of ambiguity of a particular study or report, team members consulted and discussed whether a paper met criteria for inclusion. A total of 70 studies and reports met inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Selected studies were reviewed, data were extracted and organised, and relevant information was charted under the following headings: (i) author, year of publication, study location and topic area; (ii) study design and purpose; (iii) study population and setting; (iv) methods; and (v) findings. A narrative approach was used to capture dominant and important themes that emerged. Thematic analysis was used to focus attention on context and commonalities across included studies and reports, which was guided by the original research question (Mays et al. 2005).

Findings

The 70 included articles covered 20 years from 1994 to 2014. Studies and reports were primarily descriptive or exploratory, and focused mainly on breast and cervical cancer screening among SA immigrant women (Table 1). A numerical summary was created to provide an overview of the distribution of studies by geographical location, type of cancer screening, research methods and main topic areas (Table 2). In the following paragraphs, the descriptive findings will be presented and include study design, samples, the type of screening and country of origin. Thereafter, the thematic analysis of findings will be discussed, including the four main themes emerging across all included studies.

| Author (s), year, location and topic | Study design and purpose | Study population and setting | Methods | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | ||||

|

Asanin and Wilson (2007) Toronto, Canada Health Services Access |

Qualitative: Grounded Theory Explore immigrants’ perspectives on determinants of health and access barriers |

53 immigrants Female, 79.3% and male, 20.7%; Pakistan, 20.8%; India, 15.1% (also China, Romania and other) |

Purposive sampling: Neighbourhood Health Centre Focus groups (6) |

Geographic accessibility to care Economic accessibility Sociocultural accessibility |

|

Austin et al. (2009) London, UK Colorectal Cancer Screening |

Qualitative: Exploratory Examine beliefs and barriers towards colorectal cancer screening and strategies to increase flexible sigmoidoscopy |

53 participants Female, n = 33; Male, n = 20 Gujarati Indian, n = 18 and Pakistani, n = 14 (also, African-Caribbean, White British) |

Purposive sampling: Community groups Focus groups (9) |

Perceived severity, susceptibility, benefits and barriers to screening Psychosocial barriers Lack of symptoms Culturally influenced barriers and Gender |

|

Banning and Hafeez (2010) Lahore, Pakistan and London, England Breast Cancer Screening |

Qualitative: Descriptive Examine Pakistani Muslim women breast health awareness and cultural correlates in two countries |

44 Pakistani Muslim women: Lahore (n = 24) and London (n = 20) |

Purposive sampling: Banks, financial institutions and cancer hospitals Focus groups (6) |

Knowledge and factors associated with breast cancer Image of breast cancer Knowledge of breast cancer screening |

|

Black and Zsoldos (2003) Hamilton, Canada Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening |

Qualitative: Descriptive Examine knowledge and beliefs related to cancer and screening among immigrant women |

46 Immigrant women: India, n = 8 and Pakistan, n = 13 (also, Chinese and Vietnamese) |

Purposive sampling: Community groups, agencies and cultural centres Focus groups (4) |

Indian and Pakistani women only: Beliefs, experiences and practices Knowledge and information sources Accessibility and interventions |

|

Bottorff et al. (1998) Vancouver, Canada Breast Health Practices |

Qualitative: Critical ethnography Examine South Asian women's beliefs, attitudes and values related to breast health practices |

50 South Asian immigrant women: Sikh (n = 25); Hindu (n = 9); Muslim (n = 14); and Christian women (n = 2) | Convenience and networking sampling: Interviews; second interviews with 12 women; new focus groups (n = 30) |

Woman's calling Cancer beliefs Taking care of breasts: Holistic practices Accessing services: Lack knowledge |

|

Bottorff et al. (2001a) Vancouver, Canada Cervical Cancer Screening |

Qualitative: Case study Explore successes and challenges of Pap test screening services for three populations; Asian, South Asian and First Nation women |

South Asian immigrant women: Hindu, Sikh, Muslim women (n = 20) and key informants (n = 5) (also, Asian and First Nations) |

Purposive sampling from cervical cancer screening clinics One-on-one interviews and key informant interviews |

South Asian: Reluctant to discuss cancer or cervical cancer Interplay between cultural values and health structure Cross-case analysis: Lack of comprehensive or holistic health services |

|

Bottorff et al. (2001b) Vancouver, Canada Health-seeking behaviours |

Qualitative: Critical ethnography Explore South Asian immigrant women's health-seeking behaviours |

South Asian immigrant women: Sikh (n = 49); Hindu (n = 12); Muslim (n = 14); and Christian (n = 3) |

Purposive sampling: South Asian community Face-to-face interviews (50) and focus groups (30) |

Context of women's health Speaking about health concerns Seeking validation Unspoken concerns |

|

Choudhry (1998) Toronto, Canada Health Promotion |

Qualitative: Ethnography Explore South Asian Indian women's health-promoting practices |

20 Hindu and Sikh (first generation) women |

Key informants community recruitment Open-ended, semi-structured interviews in home |

Value of being healthy Spiritual well-being Barriers to Health Promotion Changes in Lifestyle Behaviours |

|

Choudhry et al. (1998) Toronto, Canada Breast Cancer Screening |

Qualitative: Descriptive Explore knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices of South Asian women |

57 South Asian (first generation) women; India (n = 44); Pakistan (n = 14); Bangladeshi (n = 1); Indian from East Africa (n = 2) |

Key informant network community sampling One-on-one interviews |

Breast cancer knowledge Attitudes/Beliefs Mammography Barriers |

|

Forbes et al. (2011) London, UK Breast Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Examination of ethnic variation in breast cancer awareness and barriers to presentation |

2077 women approached: 333 (22%) South Asians: Bangladeshi, 34%; Indian, 29%; Pakistani, 23% (also white British and black women) | Household door-to-door sampling (81% participated) |

Barriers: South Asians report worry, embarrassment and lack confidence Knowledge and awareness: South Asian less likely to know of screening or symptoms |

|

Gesink et al. (2014) Ontario, Canada Breast, Cervical and Colorectal Cancer Screening |

Qualitative: Grounded Theory Explore communities of under- and never-screened populations |

Health service providers (n = 19) Community members (n = 121): Hindi-Urdu, Indo-Caribbean (also, Latina, Afro-Caribbean and White) Male and female |

Community outreach via informants 16 focus groups (under- and never-screened groups) |

Immigrants ONLY Lack of knowledge: Cancer, risks, screening, tests, health system Barrier: Stigma and taboo of screening especially for men Literacy and communication barriers |

|

Karbani et al. (2011) West Yorkshire, UK Breast Cancer Screening |

Qualitative: Descriptive Explore attitudes, knowledge and understanding of breast cancer and preventive health in South Asian women |

Breast cancer patients: Pakistani Muslims (n = 12), Bangladeshi Muslims (n = 2), Indian-Hindus (n = 2), Indian Sikhs (n = 8) and significant others (n = 14). Male and female |

Purposive sampling: Three hospitals One-on-one interviews (11) with significant other; at home (17), breast cancer support centre (7) |

Knowledge and awareness Knowledge of breast cancer and symptoms Cultural beliefs and practices of cancer Social support |

|

Matin and LeBaron (2004) San Francisco, California, US Cervical Cancer Screening |

Qualitative: Descriptive Explore attitudes and barriers towards cervical cancer screening, in Muslim women of Middle Eastern background |

Key informants (n = 5) Muslim women; first/second-generation (n = 15) Indian & Pakistani (also Afghan, Palestinian, Egyptian, Yemenese) |

Community recruitment: Non-profit organisation Key informant: Telephone Focus groups (3) |

Key Informant: Mammograms, CBE and Pap test Focus Groups: Muslim values of virginity and bodily privacy; Family involvement in healthcare |

|

Meana et al. (2001a) Toronto, Canada Breast Cancer screening |

Qualitative (1)/Quantitative (2) Aims: (1) examine meaning of breast cancer and screening; (2) explore physician-related barriers to recommendation |

(1) Tamil women: n = 30, 50 years of age and older (2) Physicians: n = 100 in Tamil neighbourhoods Male and female |

Purposive sampling: South Asian Women's Centre list Focus groups (n = 3) (2) Dill man method: Three questionnaires |

(1) Lack of awareness or exposure to breast cancer; perceived causes or risk; misunderstanding reason for tests; belief in karma; social stigmatisation; and embarrassment |

|

Lobb et al. (2013) Peel, Canada Breast, Cervical and Colorectal Cancer Screening |

Qualitative: Concept mapping Examine barriers to population-based screening among SA immigrants |

South Asian immigrants, South Asian primary care physicians and community service representatives (Part 1, n = 53 and part 2, n = 46) Male and female |

Snowball and network sampling: (1) Brainstorming: South Asian immigrants, n = 24 (2) Rating and sorting: South Asian immigrants, n = 15 |

Highest ranking barriers Limited knowledge among residents Ethno-cultural discordance Health education programmes Cost: Ranked second among immigrants |

|

Oelke and Vollman (2007) Alberta, Canada Cervical Cancer Screening |

Qualitative: Exploratory Explore South Asian Sikh women's knowledge, understanding and perceptions of cervical cancer screening |

53 Sikh women |

Purposive maximum variation sampling: Community, public health and other agencies Interviews plus focus groups to extend and validate |

Inside/Outside; Knowing Circle; Prevention Circle; Family Circle; Community Circle; Healthcare System Circle |

|

Pfeffer (2004) Hackney, UK Breast Cancer Screening |

Qualitative: Exploratory Examine women's decision to accept or refuse letter of invite to National Health Service Breast Screening Programme |

146 women: Gujarati, Punjabi (n = 36) (also black Afro-Caribbean, Cantonese, Somali, Sylheti, Turkish, White) |

Purposive sampling: Screening unit (inner city Hackney) Focus groups (n = 20) |

Causes Personal risk of breast cancer between themselves and breast cancer candidates Factors for compliance or non-compliance |

|

Poonawalla et al. (2014) New Jersey, Chicago, US [2008–2010] Breast Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Examine attitudes of South Asian women towards breast health and breast cancer screening |

124 South Asian women India (91.9%), Pakistan (3.2%), Bangladesh (0.8%), Nepal/Bhutan/Sri Lanka/Maldives (1.6%), Others (2.4%) |

Purposive sampling: Community recruitment South Asian General Health Survey with Champions revised Health Belief scale |

Motivation: High among South Asian Low self-perceived risk or fear Fewer barriers to mammography |

|

Randhawa and Owens (2004) General cancer services Luton, UK |

Qualitative: Descriptive Explore the meanings of cancer and perceptions of cancer services among South Asians |

48 male and female: Indian Gujarati, Indian Punjabi, Pakistani Punjabi and Bangladeshi Sylheti |

Purposive sampling: Non-professionals and professionals in cancer care Focus groups (5) |

Knowledge of cancer Experiences of cancer Causes of cancer Cancer services |

|

Taskila et al. (2009) West Midland Region, UK Colorectal Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional survey Examine factors that contribute to negative attitudes towards uptake of colorectal cancer screening in primary care |

11,355 surveys Indian (n = 240); Pakistani and Bangladeshi (n = 45) (also black Caribbean, black African, Chinese and Mixed) Male and female |

Convenience sampling: 19 general practices 11,355 surveys (53% response rate) |

53% response rate 1543 (14%) had negative attitudes; men >65 years more likely to have negative attitudes; Indian ethnic background >negative attitudes than white ethnic individuals (OR 1.70, CI 1.18–2.46) |

|

Thomas et al. (2005) Brent and Harrow, UK Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening |

Qualitative: Descriptive Examine minority ethnic population's perceived barriers to breast and cervical cancer screening |

135 participants: Asian Indian (n = 26); Pakistani (n = 16); Indian subcontinent (n = 9) Male and female (>females) |

Purposive sampling: Community, family practices, settlement and cultural agencies Focus groups |

Knowledge of cancers Beliefs and attitudes to cancer Access and barriers to screening services Cultural beliefs Relationship with health professionals |

| (B) | ||||

|

Ahmad et al. (2011) Toronto, Canada Breast Cancer Screening |

Qualitative: Concept mapping Examine South Asian women's beliefs and barriers to breast cancer screening |

60 South Asian immigrant women Language: Punjabi (26.7%); Urdu (43.3%); Hindi (30%) |

Purposive sampling: Community agency Brainstorming (n = 3), Sorting and Rating (n = 3), and Interpretation (n = 1) |

85% had never had mammography Three most important barriers: Lack of knowledge, fear of cancer, and language and transportation Significant differences: Years in Canada |

|

Ahmad et al. (2004) Toronto, Canada Health Promotion and Prevention |

Qualitative: Exploratory Explore Chinese and East Indian immigrant women's health promotion experiences and perceptions |

46 immigrant women East Indian (n = 24), Chinese (n = 22) |

Purposive sampling: Client lists at immigration and settlement organisations Focus Groups (8) |

East Indian Data Only Barriers to health information Facilitators of health information Credibility of health information Popular sources of information after immigration |

|

Amankwah et al. (2009) Calgary, Canada Cervical Screening |

Cross-sectional study Examine visible minority women at high risk of not having Pap tests, and the reasons for not having the test |

South Asian (n = 832) Other Asian (n = 620) |

Random sampling: Household of those 12 years+ Canadian Community health Survey (CCHS), cycle 1.1 and cycle 2.1 |

Reasons for NOT having Pap: Not ‘gotten around to it’; not necessary Never had Pap test: South Asians, second highest percentage (22.4%) Had Pap test >3 years ago: South Asians 2.2, lowest among all groups |

|

Bierman et al. (2009/2010) Toronto, Ontario Health Services Access |

Cross-sectional study Access to healthcare services: Rigorous and extensive literature review and use of quality indicators |

Ontario adults Canadian Community Health Survey 2005 (Cycle 3.1) and 2007 Primary Care Access Survey (Waves 4–11) Adults 25+ Male and female |

Secondary data analysis: Home Care Reporting System; Ontario Diabetes Database; Ontario Health Insurance Plan; ICES Physician Database; Canadian Institute for Health Information and 2001 Statistics Canada (Census) |

South and West Asian or Arab: 47% women and 50% men reported being very satisfied with obtaining appointments for check-ups; recent immigrants, less satisfaction than those in the country for 10 years or more |

|

Kagawa-Singer et al. (2007) California, US Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Examine Pap test and mammography screening rates in Asian American subgroup of women |

Asian American subgroups: Chinese, Filipina, South Asian, Korean, Vietnamese and Japanese American | Secondary data analysis: 2001 California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) |

South Asian (1.4%) and Cambodian (3.7%) women lowest % 65+ years of age South Asians: 65% fluent in English South Asian: Being married and regular healthcare increased likelihood of Pap test |

|

Kernohan (1996) Bradford, UK Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening |

Pre-post intervention study Examine effectiveness of community-based intervention to improve knowledge and uptake of breast and cervical screening among minority ethnic women |

1000/1628 sampled women Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi (670) |

Purposive sampling: Three neighbourhoods Closed-ended questionnaire administered before-after study |

Lowest baseline knowledge: South Asians Heard of cervical cancer and cervical smears: South Asian 35.8% and 41.8% Heard of breast cancer and mammography: South Asian 21.3% and 19.5%; all others, range 30.2%–88.3% |

|

Lee et al. (2010b) Maryland, US Healthcare Access/Screening |

Qualitative: Descriptive Examine factors that influence access to healthcare among 13 different Asian American communities |

174 participants: Asian Indian (3.5%); Nepali (5.2%); Pakistani (9.8%) Male (45.4%); female (54%) |

Purposive stratified and convenience sampling: Community leaders, agencies plus advertisements Focus groups (19) |

Structural, individual and financial barriers Cultural attitudes Women face multiple barriers Preference for physicians |

|

Marfani et al. (2013) Baltimore-Washington, US [Secondary analysis] Breast Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional survey Examine how acculturation moderates association between anxiety and breast screening in Asian Indian women |

512 Asian Indian American women approached (84.4% response) |

Purposive sampling: Temples, churches, Gurudwaras, mosques, Jain Centre and other August 2005 to February 2006 |

Anxiety: Associated with information seeking and mammography Perceived barriers to screening: Less likely to get mammogram Acculturation: Uptake |

|

Meana et al. (2001b) Toronto, Canada Breast Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional survey Examine Tamil women's self-reported barriers and incentives to breast health behaviour |

122 Tamil women: Homemakers (49%); employed outside home (41%); retired (7%) | Purposive sampling: South Asian community centres and a temple |

Had NEVER had a mammogram: n = 52. Predictors were higher education, more time in North America (mean years, 5.25, SD 2.79) Breast cancer screening beliefs and barriers |

|

Menon et al. (2012) Chicago, US Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional survey Examine breast and cervical cancer screening rates in South Asian communities |

198 participants: First-generation South Asian immigrant women Majority from India (86.5%) |

Purposive sampling: Community agencies Questionnaire: Cancer screening beliefs, social support, medical mistrust, family resources, communication and acculturation |

EVER had mammogram: 64.8%; more likely to have mammogram if in US >5 years, if had regular family physician, and 60+ years than those never screened; 5.6 times more likely to report EVER having a mammogram if also had Pap test; 33% EVER had a Pap test or vaginal examination |

|

Robb et al. (2008) United Kingdom Colorectal Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Examine ethnic minorities’ cultural beliefs about colorectal cancer screening with flexible sigmoidoscopy |

Indian (234); Pakistani (166); Bangladeshi (63); Caribbean (126); African (108); Chinese (53); white British (125) Male and female |

Ethnibus survey used Quota random sampling with 2001 Census: Sampling individual households (75%–80%) purposively: 875 Interviews with ethnic minorities |

Perceived causes of CRC: 40% did not know, 65% Bangladeshi Interest in CRC screening: 68% male, younger, higher socioeconomic status Lack of interest: Bangladeshi not interested; Pakistani, not unless ‘vital’ Perceived community barriers: 95% ethnic groups said ‘shame’ and ‘embarrassment’ |

|

Rudat (1994) England and Wales, UK Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Examine awareness, experiences and attitudes of health-related services in South Asian women |

Asian Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi populations (mammography 50–74 years; Pap test 16–74 years) Male and female |

Purposive and random sampling: Households using 1981 census for origin of birth to select sample during July and August, 1992, MORI Health Research Unit; Health Education Authority and NHS Ethnic Health Unit |

Breast cancer screening, 50–70 years: Asian Indian (14%), Pakistani (18%), Bangladeshi (14%), UK born (41%) Cervical screening, 16–74 years: Asian Indian (37%), Pakistani (32%), Bangladeshi (28%), UK born (60%); Ever heard of Pap, Asian Indian (70%), Pakistani (54%), Bangladeshi (40%), UK born (85%) |

|

Sadler et al. (2001) California, US Breast Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional survey Examine Asian Indian women's breast cancer knowledge, attitudes and screening behaviours at baseline to assess effectiveness of education |

194 Asian Indian women 20–72 years of age |

Purposive sampling: Grocery stores (59.8%), religious sites (34%), cultural events (4.1%) and theatres (2.1%) |

Baseline: Women 40+, 61.3% had mammogram within 12 months; 45.4% had knowledge Barriers to participating in early detection education for breast cancer: 58.5% lack of time; 8.2% language |

|

Somanchi et al. (2010) Baltimore-Washington, US Breast Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional survey Examine breast cancer screening adherence and predictors for mammography use in Asian Indian women |

512 Asian Indian American women approached to complete survey |

Purposive sampling: Eight Hindu temples, four churches, three Sikh Gurudwaras, two Muslim Mosques and Jain Centre; and other community settings Questionnaires |

Response rate 84.4% Factors associated with screening within 2 years and adherence to guidelines Had mammogram within 2 years: 24.6% women in the US for ≤10 years and 75.4% women lived in the US for >10 years Barrier to screening: 29% ‘no reason’, 22% no problems with breasts, 12% test ‘too expensive’, and 11% lack of physician recommendation |

|

Wu et al. (2006) Michigan, US Breast Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Examine Asian American women's beliefs and practices related to breast cancer screening |

125 women Asian Indian (38) (others Chinese and Filipino women) |

Purposive sampling: Various community and ethnic agencies, religious, academic or other organisations Survey: Susceptibility, severity, benefits and barriers |

Women 40+: 64% had mammogram; those in US ≥10 years reported regular mammogram more so than recent immigrants; moderate- to low-income Asian Indians had greater barriers – did not feel at risk for breast cancer and more likely to lack knowledge of where to get mammogram Common barriers across all groups: Examination by male health practitioner |

| (C) | ||||

|

Ahmad et al. (2005) Toronto, Canada Breast Cancer Screening |

Before-After Intervention Examine behaviour change in South Asian immigrant women's breast cancer knowledge, beliefs and self-efficacy |

74 South Asian immigrant women Ethnic identity: South Asian (48.6%), Canadian (5.6%) |

Purposive sampling: Immigration re-settlement agencies and family practices Intervention: 10 Hindi and Urdu breast cancer risk and screening articles in ethnic paper |

Pre-Intervention: 20% correct on knowledge scores; 33.3% ‘ever performed’ clinical breast examination; 46.4% reported ‘ever having had’ an examination; low knowledge of incidence, risk factors, age to begin screening, breast self-examination, clinical breast examination and mammography |

|

Ahmad & Stewart (2004) Toronto, Canada Breast Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Examine self-perceived barriers to clinical breast examination (CBE) in South Asian women |

52 South Asian immigrant women | Purposive sampling: Six family physicians who spoke language of target population |

41% had one periodic health examination; 83% had heard of CBE; 38.5% ‘ever had’ CBE; 2/3 reported heard about breast screening Knowledge: 17% unable to correctly answer; 73%, answered <50% questions Top Barriers: Not knowing how CBE performed or who to ask |

|

Bansal et al. (2012) Scotland, UK Breast Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Examine breast cancer screening uptake taking into consideration ethnic variation for women in Scotland |

First routine breast screening (women 50–53 years): Pakistanis (31.3%), Indians (14.8%) (also Chinese, Caribbean, black Scottish and Mixed) |

Secondary data analysis: Community Health Index, Scottish Breast Screening Programme, Census 2001, and National Health Service Breast Screening Programme |

138,374: 2002–2008 NHSBSP 23% of invited cohort did not have breast screening; non-attendance higher in ethnic groups versus white Scottish women; non-attendance relative risk highest among Pakistani, Other South Asian and Indian |

|

Bharmal and Chaudhry (2012) US [April to July 2001] Breast, Cervical and Colorectal Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study (secondary analysis) Examine preventive health examination uptake rates among South Asian immigrants |

405/1913 surveys sent out returned 225 women: 69% born in India; 13% born in Pakistan Male and female (more males) |

Purposive sampling: South Asian households, preventive examinations (blood pressure, cholesterol, mammogram, Pap, colorectal cancer screening, and tetanus, pneumococcal and influenza vaccinations) |

Up-to-date status of all tests, low among SA immigrants; men, 26.1% and women, 24.9%; usual source of care greater odds of being up to date Women less likely to be up to date with all preventive health examinations |

|

Boxwala et al. (2010) Michigan, US [May–Sept 2007] Breast Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Examine factors associated with breast cancer screening in Asian Indian women |

205 Asian Indian women participated (20% declined) | Purposive sampling: Places of worship, health fairs/events, women's event and community fairs |

63.8% of women had mammogram (2 years) Most likely to be screened: College education; lived in US for more years; perceived screening as useful; received recommendation from provider |

|

Brotto et al. (2008) Vancouver, Canada, and New Delhi, India Cervical Cancer Screening and Breast Self-examination |

Cross-sectional study Explore reproductive health knowledge and behaviours among women from four distinct ethno-cultural groups |

663 women: Indian (145) women; Indian Canadian (Indo-C) women in Canada (29); 267 East Asian women in Canada (267); Euro-Canadian women (222) |

Purposive sampling: Online research system, students from Canada, University of British Columbia New Delhi recruitment not described |

Euro-C group most likely to have EVER had a Pap; other three groups less likely to have EVER had a Pap; no difference in Pap use in Indian and Indo-C Knowledge: Pap test use greater in all other groups compared to Indian women |

|

Chaudhry et al. (2003) US Cervical Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Examine Pap test use (within 3 years) in South Asian women |

1913 South Asian households (405 returned) Of 1508, 615 responded and 225 women |

Purposive sampling: South Asian households endorsed by two Indian/Pakistani associations |

42% response rate South Asian women: Less likely to have Pap smears (73% versus 78%, P < 0.001) or usual source of care (74% versus 78%, P = 0.007) Predictors: Low Pap use, low socioeconomic status, unmarried, lesser years in US |

|

De Alba et al. (2005) California, US [2001] Cervical Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Assess race/ethnicity and Hispanic and Asian subgroups of women in California on Pap test use |

25,228 women: White (49.6%); Hispanic (30.1%); Asian* (11.3%), Black (5.4%), Other (3.6%) *South Asians (9.4%) |

Random sampling: Telephone digit dialling using CHIS |

South Asian less likely to report recent Pap or EVER having had a Pap Subgroup analysis: Filipinos and Koreans were most likely to report recent Pap than South Asians, Chinese and Vietnamese |

|

Glenn et al. (2009) California, US Breast, Cervical, Colorectal and Prostate Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Examine cancer screening rates and demographic correlates associated with four common cancers, breast, cervical, prostate and colorectal |

344 South Asians Indian (41%); Pakistani (25%); Bangladeshi (20%); Sri Lankan (11%); Nepali (2%); Other (1%) Male (48%), female (52%) |

Purposive sampling: Places of worship and community events South Asian Network and UCLA School of Public Health collaboration |

62% EVER had a mammogram, 63% EVER had a Pap. 34% and 57% met screening guidelines; highest mammogram rates in Sri Lankans, and lowest in Pakistanis Colorectal cancer: 33% of eligible sample EVER had screening; 25% met guidelines; compared to men, women less likely to have screening |

|

Gomez et al. (2007) California, US Breast Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Identify characteristics that inhibit mammography screening in Asian American women |

1521 study subjects Asian subgroups: South Asian (n = 125) (also Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos, Koreans, Vietnamese) |

Random sampling: Telephone digit dialling under-represented areas/ethnic groups using CHIS |

35.5% of all Asian women 41 years+ reported no mammogram in past 2 years High-risk South Asian: Had no health insurance; with health insurance, <50 years and unemployed; with health insurance, <50 years, employed and non-citizens |

|

Gupta et al. (2002) Toronto, Canada Cervical Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Describe factors that limit Pap test use among South Asian women |

62 Tamil students and 62 Tamil women | Purposive sampling: South Asian university students and community centres |

Lack of knowledge of Pap test: 16% students and 66% women Ever had Pap: 27% students, 23% women; common reasons, self-perceived lack of need or knowledge. Those who had Pap test, family doctor recommendation was important predictor |

|

Hasnain et al. (2014) Chicago, US Breast Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional survey Examine breast cancer and screening beliefs and factors that influence mammography among Muslim women |

207 Muslim (first generation) Middle Eastern (ME), South Asian (SA): Pakistan (30%), Palestine (21%) and India (17%) |

Purposive sampling: Community outreach Measures: Breast health, beliefs scale, acculturation and importance of mammography |

Mammography: 23.6% ME never screened compared to 38% SA; 63% ME adherent to guidelines compared to 41% SA Acculturation: More years in US significantly associated with screening among SA group |

|

Islam et al. (2006) Seven cities in the US Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional Examine breast and cervical cancer screening in South Asian women |

98 South Asian women Indian (n = 72), Bangladeshi (n = 13), Pakistani (n = 5), Other (n = 8) |

Purposive and random selected individuals: South Asian surname list Behavioural Risk Factor Surveillance and National Health Interview Surveys |

67% EVER had Pap, 54% in recent year 40 years and older (2/3): 70% ever had mammogram, 56% in recent 2 years Predictors of EVER having Pap and mammogram: Insurance (strongly associated) EVER had Pap: Usual source of care, higher language proficiency, education, more years in US and marital status |

|

Lee et al. (2010a) California, US Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Assess cancer screening disparities among Asian American women compared to non-Latina white women |

Non-Latina white (88.6%) Six Asian American (AA) groups (11.4% aggregated): South Asian, 0.9% (also Chinese, Filipinos, Koreans, Vietnamese, Japanese) |

Random sampling: Telephone digit dialling using CHIS |

Predisposing factors: AA, greater % married Enabling factors: South Asians, high income Need factors: Vietnamese women reported 2.9–3.7 doctor visits/year Cancer screening: Asians highest Pap use and lowest mammography rates (40.3%) Predictors: More time in US increased screening |

|

Lee et al. (2011) California, US Colorectal Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Examine colorectal cancer screening uptake in ethnic minority populations in the US |

Asian American and Pacific Islanders (AAPI): Chinese, Koreans, Japanese, South Asians, Vietnamese, Filipinos and Pacific Islanders Male and female |

Random sampling: Telephone digit dialling using CHIS (2001, 2003, 2005) |

Greater females: South Asians, Pacific Islanders Screening disparities: Filipinos, Koreans and South Asian significantly lower probability of colorectal cancer screening versus non-Latino white reference group |

|

Lofters et al. (2010) Toronto, Canada Cervical Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Examine cervical cancer screening rates among immigrant women |

Ontario women (18–69 years) Immigrants identified: More likely to be represented among low-income neighbourhoods |

Secondary data analysis: Ontario Physicians’ Database, Landed Immigrant Data System, 2006–2008 |

Lowest adjusted rate ratio in both age groups: South Asia, Middle East and North Africa Predictors: Neighbourhood income associated with Pap; lower Pap rates for those not in primary care model and <10 years in Canada; 21% had Pap in older South Asian, lowest income neighbourhoods, not in primary care |

|

McDonald & Kennedy (2007) Canada Cervical Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Examine cervical cancer screening among immigrant women and other factors that influence screening |

8327 immigrant women South Asian, South-East Asian (also white, black, Hispanic, Arab/West Asian, Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Filipino) |

Random sampling: 1996 National Population Health Survey and 2002–2003 Canadian Community Health Survey | Canadian-born women: Lowest Pap rates among South Asian, South-East Asian, and West Asian/Arab women, 15–25% Pap use compared to >70% for native-born white women of similar socioeconomic status |

|

Menon et al. (2014) Chicago, US Colorectal Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Assess predisposing and enabling factors that influence CRC screening uptake among South Asian immigrants |

275 first-generation South Asian immigrants Male and female 79.1% lived in US 5+ years |

Purposive sampling: Community agency recruitment Measures: Cancer beliefs, medical mistrust, acculturation, social support and family resources |

2.2% perceived risk of colorectal cancer; 8% had FOBT, 13.6% had endoscopy Enabling predictors of FOBT: Language acculturation and medical mistrust Enabling predictors of endoscopy: Income and residence. Predisposing predictors of endoscopy: Language acculturation, perception of risk and FOBT |

|

Mehrotra et al. (2012) New Jersey and Chicago, US Health Services Access |

Cross-sectional study Examine self-health perception, health-related behaviour, health services utilisation and satisfaction with medical care for Asian Indians |

1250 participants: Gujarati (53%), Hindi (14.4%), Telugu (9.5%) and others (23.1%) Male (54.1%) |

Purposive sampling: Cultural, civilian or religious events 2008–2010 Self-administered questionnaire |

73.5% response (n = 1250) 83.7% had routine medical visit (2 years); uninsured (n = 543) and 26.5% did not visit physician due to cost; 47.9% reported Pap use; 37.1% reported BSE; 40.1% reported mammography use |

|

Misra et al. (2011) Seven cities in the US Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Determine cancer screening practices in Asian Indians in the US |

2900 invitations to Asian Indians Male (60.4%), female (38.6%) |

Purposive sampling: Mailed invitation and telephone National Health Interview Survey/Cancer Control Module (with 62% response) |

62% response Men more likely to do FOBT (45.2% versus 30.6%) and colonoscopy (45.5% versus 32.6%). Predictors: US ≥10 years, greater odds of all screening; >80% higher education, greater odds Pap and FOBT; insurance, main predictor |

|

Patel et al. (2012) New York, US Health Services Needs |

Cross-sectional study. Assess needs among a Bangladeshi sample |

184 Bangladeshi women Response rate (n = 167) |

Random sampling: Household door-to-door sampling New York City Community Health Survey |

90.8% response rate: 45.4% (age standardised to US census) never had Pap; Bangladeshi more likely to never have received a Pap compared to other groups 40+ years (age standardised to US census): 24% had not received mammogram >2 years |

|

Pourat et al. (2010) California, US [2003] Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Evaluate access and acculturation related to breast and cervical cancer screening for Asian Americans |

2161 participants South Asian (n = 199) (also Chinese, Filipinos, Japanese, Koreans, Vietnamese) |

Random sampling: Telephone digit dialling CHIS, telephone survey with Asian Indian staff |

Mammogram rates: South Asians (39%) lowest. English proficiency, South Asians (64%) lowest. Predictors of CBE in South Asians: Usual source of care increased likelihood of CBE; lack of insurance decreased CBE. Pap test in South Asian: Lack of usual source of care decreased likelihood |

|

Price et al. (2010) Coventry and Warwickshire, UK [15 years tracking] Breast and Colorectal Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Determine breast and bowel cancer screening uptake in women (including South Asians) in England |

72,566 invited to bowel screening: Non-Asian (n = 69,027); South Asian (n = 539) 18,730 women invited to breast screening; Non-Asian white British (n = 17,857); South Asian (n = 873) |

Secondary data analysis: National Health Services bowel programme data (2000–2002); Subset of women invited to breast screening, rounds 1, 2, 5 (1989–2004) also used | Greater proportion of South Asians completed only (1) screening test 44% versus 27.3% versus non-Asian women. South Asian women less likely to complete FOBT than non-Asian women, 49.5% versus 82.3%. South Asian women no more likely to have FOBT if had mammogram than those who did not have either test |

|

Quan et al. (2006) Canada Health Services Access |

Cross-sectional study Examine the utilisation of health services by White and visible minorities in Canada |

7057 visible minorities: South Asian (n = 1447) (also, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Filipino or South-East Asian, Arab/West Asian, black, Latin American, White) Male and female |

Random sampling: Household, 12+ years Canadian Community Health Survey, cycle 1.1 |

Minorities significantly younger, more likely married, completed higher education and have income <$30,000; 51% in Canada for ≥10 years. Utilisation: Less likely to use PSA, mammogram or Pap test |

|

Rashidi & Rajaram (2000) Nebraska, US Breast Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Examine knowledge and frequency of breast self-examination in Middle Eastern (ME) Asian Islamic immigrant women |

50 ME Asian Islamic women approached 39 (78%) women participated: Pakistan (n = 18) (also from Afghanistan, Israel/Palestine, Jordan) |

Purposive sampling: Recruitment from Islamic Centre in Omaha | Knowledge of breast cancer and BSE: 38 said <1 once a year and one monthly; 85% heard of BSE; 74% did not perform BSE. Learn to do BSE: 79% not taught. Clinical Breast Exam: 82% never had. Mammogram: 28% of women ≥40 years |

|

Robb et al. (2010) England, Wales, and Scotland, UK Breast, Cervical and Colorectal Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Examine awareness of three national cancer screening programmes among ethnic groups in UK |

ONS: 2216/3653 (61%) 2208 completed cancer awareness content Ethnibus: 1500, six ethnic groups (October, 48% and November, 56%): Indian (n = 467); Pakistani (n = 333); Bangladeshi (n = 126) (also Chinese, Caribbean, African) |

Random sampling: Households, in-person computer-aided Office of National Statistics Opinion (ONS) and Ethnibus surveys/New cancer module |

ONS survey: White sample, highest knowledge of breast (89%) and cervical cancer (84%) screening programmes and lowest among Ethnibus sample (69% breast, 66% cervical). Caribbean had greater awareness of breast and cervical cancer programmes than Indians Colorectal cancer screening: Bangladeshi greatest awareness, 40%, than other six groups |

|

Surood & Lai (2010) Alberta, Canada Health Services Utilisation |

Cross-sectional study Examine the effect of multiple factors on western health services utilisation in older South Asian immigrants |

220/329 (66.9%) South Asians 55+ years: Sikh (55.5%); Muslim (20.5%); Hindu (20%) Male (55.5%), female (44.5%) |

Random sampling: Surname list scan and telephone survey |

Predisposing: Age significant explaining 7.2% of variance in healthcare utilisation Enabling: Effect of age remained with lower income. Cultural variables to using more health services: Hindu, longer residence, more knowledge and receptiveness of preventive health services including screening |

|

Sutton et al. (2001) Wakefield, UK Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Determine breast and cervical cancer screening uptake in West Yorkshire, England |

852 South Asian women: 5.2% of 16,475 possibilities South Asian and non-Asian women matched by age, and general practice and indirectly for residence |

Secondary data analysis: Eight physician general practices, West Yorkshire Central Services Agency, primary care health registration of Wakefield Health Authority | Cervical cancer screening: 67% South Asian and 75% of non-Asians had acceptable cervical screening histories; for two practices, South Asians had greater coverage. Breast cancer screening: 53% of South Asians and 78% of non-Asians had acceptable breast screening histories; South Asians less likely to be screened or to be overdue |

|

Szczepura et al. (2003) UK Colorectal Cancer Screening |

Part 1 Cross-sectional study: Examine colorectal cancer screening uptake with return of FOBT kit; Part 2 Cross-sectional study: Understand beliefs and attitudes with FOBT responders and non-responders; Part 3 Qualitative study: Assess reasons for behaviour and motivation |

Part 1: 132,992 (62%) Part 2: Hindu-Gujarati (n = 194); Hindu-other (n = 87); Muslim (n = 191); Sikh-Punjabi (n = 311) Part 3: Bangladeshi (n = 44), Punjabi Sikh (n = 35), Gujarati (n = 31), Pakistani/Urdu (n = 13) Male and female |

Purposive sampling: Bowel screening programme recruitment | Part 1: South Asian, 30.8%–43.2% uptake versus 63.3% in non-Asians; lower than white-Europeans. Part 2: South Asian, lower perceived susceptibility, ‘embarrassing’, low confidence and social support. Part 3: (1) Knowledge and fear of cancer, afraid, fatalistic; (2) Attitude towards screening, lack knowledge; (3) Reasons for not screening, lack of knowledge, FOBT not appealing, language and not concerned about health |

|

Szczepura et al. (2008) Coventry and Warwickshire, UK Breast and Colorectal Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Examine patterns of uptake for breast and bowel (began in 2000) cancer screening for two organised screening programmes in UK |

240,140 participants (round 1 and 2): South Asians (n = 8649)-Hindu-Gujarati, Hindu-Other, Muslim, Sikh, and Other South Asian Male = Female |

Secondary data analysis: Session 1 (2000–2002); session 2 (2003–2005) of National Bowel Cancer Screening Programme |

South Asians had statistically significant low-unadjusted colorectal screening uptake, 32.8% versus 61.3% for non-Asians (round 1). South Asian also had significantly lower breast screening compared to non-Asians, 60.8% vs.75.4% (round 1) with disparities slightly reduced over time. |

|

Webb et al. (2004) Manchester, England Cervical Cancer screening |

Cross-sectional study Determine cervical cancer screening uptake by ethnicity in women |

72,613 records of eligible women 30–64 years of age Ethnicity: South Asian (n = 67,830) (also Other, and Great Britain) |

Secondary data analysis: Feb 2001 electronic screening records from Manchester Health Authority |

6783 (9.3%) women South Asian. Uptake for South Asian, 69.5% versus 73.0% for non-Asians (P < 0.001). Uptake lower: Indian subcontinent origin than other South Asian women (65.6% versus 71.4%, P < 0.0001); ‘never-screened’ rate 39% for South Asians from the subcontinent |

|

Woltman & Newbold (2007) Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver, Canada Cervical Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional Examine individual and neighbourhood factors associated with cervical cancer screening among immigrant and native-born women in Canada |

Immigrant and native-born South Asian women (5.1%) (also White, Chinese, Other Asian, black, Other) |

Random sampling: Household, women 18–69 years, Canadian Community Health Survey, cycle 2.1 (2003) |

Had Pap test: 89% native-born; 65% recent and 88% long-term immigrants Odds of EVER having a Pap compared to native-born women: 0.19% recent and 0.56% long-term immigrants Least likely to EVER have had a Pap: Chinese, South Asian, or other Asians |

|

Wong et al. (2005) California, US Colorectal Cancer Screening |

Cross-sectional study Examine colorectal cancer screening rates in Asian American (AA) groups |

55,000 households, 50 years + South Asians (n = 148) (also Chinese, Filipinos, Japanese, Koreans, Vietnamese) Male and female |

Random sampling: Telephone lists from community organisations CHIS: 2001 |

64% response rate (AA) Screening lower in AA: 38% FOBT, 42% endoscopy and 58% any screen compared to non-Latino whites, 58% FOBT, 57% endoscopy and 75% any screen |

|

Wu & Ronis (2009) Breast Cancer Screening Michigan, US |

Cross-sectional study Examine AA women's beliefs, knowledge and mammogram use |

315 AA women; Asian Indian, 109 (35%) (also Chinese or Taiwanese, Koreans, Filipinos) |

Purposive sampling: Community, festivals, socials, religious and health fairs | 56% had mammogram. Of 253 completed data for regular mammogram, 33% had mammogram (last 5 years). Barriers: Recent immigrants and language |

- FOBT, faecal occult blood test.

| Geography | UK | US | Canada |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening or services | |||

| Colorectal screening | 4 | 3 | 0 |

| Breast screening | 5 | 10 | 7 |

| Cervical screening | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Breast and cervical screening | 4 | 5 | 2 |

| Breast, cervical and colorectal screening | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Breast and colorectal screening | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Health promotion/services provision | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Research methods | |||

| Quantitative: cross-sectional surveys | 10 | 25 | 11 |

| Qualitative: focus group/one-on-one interviews | 6 | 2 | 12 |

| Other: mixed methods/review/intervention study | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| General topic area | |||

| Beliefs and attitudes (Table 1A); barriers/predictors to utilisation (Table 1B) | 11 | 9 | 16 |

| Knowledge and uptake (Table 1C) | 7 | 18 | 9 |

| Total studies | 18 | 27 | 25 |

The majority of studies and reports (66%, n = 46) were cross-sectional, used surveys, examined self-report screening rates, barriers and factors associated with cancer screening participation. Cross-sectional studies that included different ethno-cultural groups often had small samples of SA immigrants or SA immigrant subgroups. Almost one-third (29%, n = 20) of studies used qualitative designs with data collection methods of focus groups, interviews and concept mapping. The remaining four studies (5%) used mixed-methods or pre/post intervention design. The majority of qualitative studies (60%, n = 12/20) examined female cancer screening or beliefs and barriers to healthcare services including cancer screening. Of the remaining studies, one interviewed breast cancer patients and their spouses (Karbani et al. 2011), one did not clarify male and female participant numbers (Randhawa, & Owens, 2004), one had almost equivalent male and female samples (Lee et al. 2010b) and five had greater female than male participants (Thomas et al. 2005, Asanin & Wilson 2007, Austin et al. 2009, Lobb et al. 2013, Gesink et al. 2014). Two mixed-methods studies also used qualitative design with one including female samples only (Meana et al. 2001b) and the other conducted with both female and male samples (Szczepura et al. 2003). Fifteen (21%) studies included colorectal cancer screening and were undertaken in the UK, US and Canada; of these, 14 included males and females. In colorectal cancer screening studies, findings varied by test procedures investigated. Four studies from the UK and Canada qualitatively examined SA immigrants’ perspectives on beliefs, barriers and reasons for colorectal cancer screening (Szczepura et al. 2003, Austin et al. 2009, Lobb et al. 2013, Gesink et al. 2014).

Thematic analysis

Through charting and thematic analysis, four dominant recurring and relevant themes were identified: (i) beliefs and attitudes towards cancer and screening including sub-themes of family as central, holistic healthcare, fatalism, screening not necessary and emotion-laden perceptions; (ii) lack of knowledge of cancer and screening related to not having heard about cancer and its causes, or lack of awareness of screening, its rationale and how to access services; (iii) barriers to access centred on individual and structural barriers to cancer prevention or screening services; and (iv) gender differences in screening comprised of rates and factors associated with screening uptake. See Table 3 for themes and sub-themes, and information on gender distribution of studies.

| Theme | Sub-theme | Study distribution and references |

|---|---|---|

|

1. Beliefs and attitudes Beliefs and attitudes towards cancer and screening |

Family as central The cultural beliefs and values associated with family such as cohesiveness, respect and honour were important findings related to sociocultural context of SA immigrants |

11 studies: one included samples of both genders |

| Bottorff et al. (1998), Choudhry (1998), Bottorff et al. (2001b), Meana et al. (2001a), Ahmad et al. (2004), Matin & LeBaron (2004), Thomas et al. (2005), Oelke & Vollman (2007), Banning & Hafeez (2010), Ahmad et al. (2011), Karbani et al. (2011) | ||

|

Holistic healthcare The perception that maintaining health also occurs informally, and involves lifestyle balance (diet, physical activity, rest, reduced stress) |

10 studies: four included samples of both genders | |

| Bottorff et al. (1998), Choudhry (1998), Bottorff et al. (2001b), Black & Zsoldos (2003), Matin & LeBaron (2004), Asanin & Wilson (2007), Bierman et al. (2009/2010), Lobb et al. (2013), Menon et al. (2014), Poonawalla et al. (2014) | ||

|

Fatalism The views associated with cancer emerged as a strong belief that it was out of individual control and led to death |

10 studies: six included samples of both genders | |

| Bottorff et al. (1998), Choudhry (1998), Meana et al. (2001a), Black & Zsoldos (2003), Szczepura et al. (2003), Pfeffer (2004), Randhawa & Owens (2004), Thomas et al. (2005), Karbani et al. (2011), Gesink et al. (2014) | ||

|

Screening not necessary The low self-perceived risk that screening was only indicated for those at risk, or those who had symptoms |

14 studies: six included samples of both genders | |

| Rudat (1994), Bottorff et al. (1998), Sadler et al. (2001), Szczepura et al. (2003), Pfeffer (2004), Thomas et al. (2005), Wu et al. (2006), Oelke & Vollman (2007), Robb et al. (2008), Amankwah et al. (2009), Austin et al. (2009), Lobb et al. (2013), Menon et al. (2014), Poonawalla et al. (2014) | ||

|

Emotion-laden perceptions Negative emotional states were reasons for not engaging in cancer screening |

21 studies: seven included samples of both genders | |

| Rudat (1994), Bottorff et al. (1998), Choudhry et al. (1998), Bottorff et al. (2001a), Meana et al. (2001a), Meana et al. (2001b), Sadler et al. (2001), Black & Zsoldos (2003), Szczepura et al. (2003), Ahmad & Stewart (2004), Pfeffer (2004), Thomas et al. (2005), Oelke & Vollman (2007), Robb et al. (2008), Austin et al. (2009), Taskila et al. (2009), Banning & Hafeez (2010), Ahmad et al. (2011), Forbes et al. (2011), Lobb et al. (2013), Poonawalla et al. (2014) | ||

|

2. Lack of knowledge Reasons for not engaging in cancer screening included limited knowledge of cancer type, the causes of cancer, awareness or types of screening tests, and access points to obtain screening |

23 studies: 7 included samples of both genders | |

| Rudat (1994), Bottorff et al. (1998), Choudhry et al. (1998), Rashidi & Rajaram (2000), Bottorff et al. (2001a), Meana et al. (2001b), Gupta et al. (2002), Szczepura et al. (2003), Ahmad et al. (2004), Ahmad & Stewart (2004), Ahmad et al. (2005), Wu et al. (2006), Oelke & Vollman (2007), Brotto et al. (2008), Robb et al. (2008), Austin et al. (2009), Wu & Ronis (2009), Banning & Hafeez (2010), Robb et al. (2010), Forbes et al. (2011), Karbani et al. (2011), Lobb et al. (2013), Gesink et al. (2014) | ||

|

3. Barriers to access Individualised or systematic reasons that impede the ability to access cancer screening |

Individual barriers The personal and individual factors that inhibit individuals from accessing cancer screening, such as language, social support, time, money and transportation |

18 studies: nine included samples of both genders |

| Kernohan (1996), Bottorff et al. (1998), Meana et al. (2001b), Sadler et al. (2001), Szczepura et al. (2003), Ahmad et al. (2004), Matin & LeBaron (2004), Thomas et al. (2005), Asanin & Wilson (2007), Oelke & Vollman (2007), Austin et al. (2009), Szczepura et al. (2008), Wu & Ronis (2009), Lee et al. (2010b), Ahmad et al. (2011), Karbani et al. (2011), Lobb et al. (2013), Gesink et al. (2014) | ||

|

Structural barriers The systemic factors inherent in the way health services are organised that limit access to cancer screening, such as physician gender, culture or recommendation |

23 studies: 10 included samples of both genders | |

| Rudat (1994), Bottorff et al. (1998), Bottorff et al. (2001a), Meana et al. (2001a), Gupta et al. (2002), Black & Zsoldos (2003), Pfeffer (2004), De Alba et al. (2005), Thomas et al. (2005), Wong et al. (2005), Islam et al. (2006), Asanin & Wilson (2007), Gomez et al. (2007), Oelke and Vollman (2007), Glenn et al. (2009), Boxwala et al. (2010), Lee et al. (2010b), Pourat et al. (2010), Somanchi et al. (2010), Karbani et al. (2011), Misra et al. (2011), Mehrotra et al. (2012), Lobb et al. (2013) | ||

|

4. Gender differences The distinct factors that affect uptake of cancer screening in SA men and SA women |

39 studies: 10 included samples of both genders | |

| Rudat (1994), Kernohan (1996), Choudhry et al. (1998), Rashidi & Rajaram (2000), Meana et al. (2001a,b), Sutton et al. (2001), Gupta et al. (2002), Chaudhry et al. (2003), Ahmad & Stewart (2004), Webb et al. (2004), De Alba et al. (2005), Wong et al. (2005), Islam et al. (2006), Quan et al. (2006), Gomez et al. (2007), McDonald & Kennedy (2007), Kagawa-Singer et al. (2007), Woltman & Newbold (2007), Brotto et al. (2008), Szczepura et al. (2008), Glenn et al. (2009), Wu & Ronis (2009), Amankwah et al. (2009), Boxwala et al. (2010), Lee et al. (2010a), Lofters et al. (2010), Pourat et al. (2010), Price et al. (2010), Somanchi et al. (2010), Surood & Lai (2010), Misra et al. (2011), Bansal et al. (2012), Bharmal and Chaudhry (2012), Mehrotra et al. (2012), Menon et al. (2012), Patel et al. (2012), Hasnain et al. (2014), Marfani et al. (2013), Menon et al. (2014) | ||

Theme 1: beliefs and attitudes

The first two sub-themes emerged as important contributors to SA immigrants’ beliefs of cancer and cancer screening uptake providing insights into the sociocultural context and use of health services including screening, whereas the subsequent three sub-themes revealed the reasons for which SA immigrants did not participate in cancer screening.

Family as central

Common beliefs included a strong sense of family cohesiveness demonstrating honour, respect and dependence (Bottorff et al. 1998, 2001b, Choudhry 1998, Oelke & Vollman 2007). Respecting and honouring family were maintained by not discussing sensitive female health-related issues such as cervical or breast cancers within the family (Bottorff et al. 2001b, Banning & Hafeez 2010) or with others in the community (Bottorff et al. 1998, 2001b, Choudhry 1998, Meana et al. 2001a, Oelke & Vollman 2007). The inability to discuss relevant health issues with others (Bottorff et al. 1998, Meana et al. 2001a) limited conversations that may have served to increase awareness of recommended preventive health practices (Bottorff et al. 2001b, Oelke & Vollman 2007). Maintaining privacy was another important concern, especially when accessing health services in smaller communities (Oelke & Vollman 2007).

In contrast, families could play an important role in validating concerns, and providing advice and recommendations (Oelke & Vollman 2007). The head of the household or a close friend sometimes provided advice on health issues or consulted on whether it was necessary to seek out physician advice (Bottorff et al. 1998, 2001b, Ahmad et al. 2004, Oelke & Vollman 2007, Banning & Hafeez 2010). Family support to access healthcare was especially important when women did not speak English (Choudhry 1998, Ahmad et al. 2011). A lack of informal support networks or extended family increased a SA immigrant woman's dependence on family members when accessing health services (Choudhry 1998, Thomas et al. 2005). For some SA Muslim women, family played a role in assuring cultural values were maintained with respect to western healthcare practices, for example, the recommendation of a Pap test for an unmarried woman went against Muslim beliefs and values (Matin & LeBaron 2004). Alternatively, some SA immigrants’ immediate family and relatives encouraged them to have screening (Oelke & Vollman 2007, Karbani et al. 2011).

Some SA immigrant women lived in patriarchal families, where their primary role was to meet family obligations including care-giving, homemaking and/or contributing by working outside the home (Bottorff et al. 1998, 2001b, Oelke & Vollman 2007). Family needs could supersede personal needs (Oelke & Vollman 2007). In other situations, SA immigrant women believed that they were not to burden their family; and so, good health maintenance was required to fulfil their obligations (Choudhry 1998, Bottorff et al. 2001b).

Holistic healthcare

A holistic approach to health was believed to be conducive to maintaining health among both SA immigrant men and women (Bottorff et al. 1998, Choudhry 1998, Asanin & Wilson 2007). Some SA immigrant women reported the belief that health maintenance involved a balance between body, mind and spirit (Choudhry 1998, Bottorff et al. 2001b, Black & Zsoldos 2003). Importance was placed on diet, physical activity, reduced levels of stress and relaxation (Bottorff et al. 1998, Choudhry 1998, Black & Zsoldos 2003). Among SA immigrant women of higher socioeconomic status, greater motivation to take care of one's health and confidence with performing breast self-examination were associated with greater perceived benefits of mammography (Poonawalla et al. 2014).

In other situations, SA immigrants’ healthcare encounters with physicians were not perceived to be holistic; rather, they were perceived to be rushed, impersonal and reserved, creating challenges and conflicts due to differing views of health (Asanin & Wilson 2007, Lobb et al. 2013). In addition, SA immigrants believed that the health system was not respectful nor did it provide accommodation for the SA culture and traditional views of health, which created ‘ethno-cultural discordance’ (Lobb et al. 2013). A physician's lack of respect and sensitivity towards Muslim women's values of modesty and virginity were issues that did not align with cultural views among some SA immigrant women (Matin & LeBaron 2004). SA immigrants also reported lower satisfaction with the routine health examination (Asanin & Wilson 2007, Bierman et al. 2009/2010). The physician's role in promoting cancer screening was believed to be important for access to cancer screening tests (Lobb et al. 2013). As well, level of trust with doctors or other healthcare workers was an enabling predictor for faecal occult blood test (FOBT) uptake among SA immigrants (Menon et al. 2014). The discordance between what SA immigrants believed and what occurred in western health systems poses challenges in promoting health and cancer screening uptake.

Fatalism

Karma and destiny were directly linked to fatalistic beliefs, whereby cancer was one's destiny determined by God (Choudhry 1998, Meana et al., 2001a, Black & Zsoldos 2003, Szczepura et al. 2003). Some SA immigrants believed that cancer was ‘incurable’ (Bottorff et al. 1998, Randhawa & Owens 2004), and not a disease that could be prevented or controlled (Meana et al., 2001a, Black & Zsoldos 2003). Beliefs associated with developing cancer included negative lifestyle behaviours such as promiscuity and physical inactivity; retribution for past sins; and a form of punishment (Meana et al. 2001a, Black & Zsoldos 2003, Pfeffer 2004). Cancer was not to be discussed with family, relatives or the community (Bottorff et al. 1998, Meana et al. 2001a, Thomas et al. 2005, Karbani et al. 2011), and for some, avoiding talking about cancer was a way to prevent affliction with the disease (Meana et al. 2001a, Thomas et al. 2005). In addition, the stigma associated with a cancer diagnosis had the potential to damage a family's reputation (Karbani et al. 2011). In particular, some male SA immigrants avoided screening because of the stigma or taboo associated with seeing a doctor to discuss cancer screening (Gesink et al. 2014).

Screening not necessary

Some SA immigrants had low self-perceived risk of cancer. This was associated with SA immigrants’ experiences in their country of origin and the belief that western-born populations were at higher risk for breast, cervical or colorectal cancers. For some SA immigrants, breast cancer was seen as a ‘white woman's disease’ (Bottorff et al. 1998) because they did not breast feed their children (Pfeffer 2004); screening was for younger women (Thomas et al. 2005); or cancer was not a risk for women of their culture (Rudat 1994, Wu et al. 2006; Poonawalla et al. 2014). Others believed that colorectal cancer was a predominantly male disease (Austin et al. 2009) or not a risk for them (Menon et al. 2014). A lack of symptoms was another reason for believing that screening was not required (Bottorff et al. 1998, Szczepura et al. 2003, Oelke & Vollman 2007, Robb et al. 2008, Austin et al. 2009), as was the perception that screening was not important or a priority (Rudat 1994, Sadler et al. 2001, Amankwah et al. 2009, Lobb et al. 2013). For some, these beliefs may have stemmed from the lack of exposure to preventive healthcare in countries of origin (Oelke & Vollman 2007).

Emotion-laden perceptions