Structured medicines reviews in HIV outpatients: a feasibility study (The MOR Study)

Funding information

This work was supported by a Merck Sharp & Dohme Investigator Award Grant to JHV.

Abstract

Objectives

Polypharmacy in people living with HIV (PLWH) increases the risks of medicine-related problems (events or circumstances involving drug therapy that actually or potentially interfere with desired health outcomes). We aimed to examine the feasibility and acceptability of a Medicines Management Optimisation Review (MOR) toolkit in HIV outpatients.

Methods

This was a multi-centre randomized controlled study across four HIV centres. In all, 200 PLWH on combination antiretroviral therapy, either > 50 years old or < 50 years with other comorbidities, were enrolled to have a MOR or received standard pharmaceutical care. The primary outcome was the difference in the number of medicine-related problems (MRPs) between intervention and standard care groups at baseline and 6 months. Acceptability, cost of the intervention and health-related quality of life were also examined.

Results

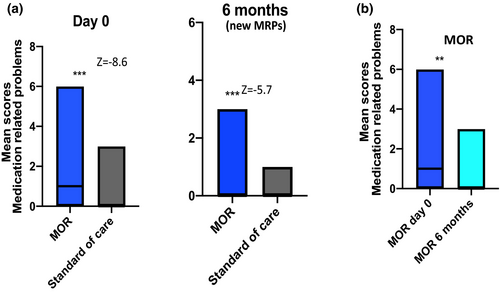

In all, 164 patients were analysed: 70 in the intervention group and 94 in the standard care group. A significant number of MRPs were detected in those patients receiving MOR compared with the standard care group at baseline (93 vs. 2; p = 0.001, z = −8.6, r = 0.6) and 6 months (33 vs. 3; p = 0.001, z = −5.7, r = 0.4). A significant reduction in the number of new MRPs at 6 months in the intervention group versus baseline was also observed (p = 0.001, Z = −3.7, r = 0.2); 44% of MRPs were fully resolved at baseline and 51% at 6 months. No changes in health-related quality of life following MOR or between MOR and standard care groups were observed. The MORs were highly acceptable among patients and healthcare professionals.

Conclusions

The MOR toolkit was feasible and acceptable, suggesting that HIV outpatient services might consider implementing MOR for targeted populations under their care.

INTRODUCTION

The introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) has transformed HIV disease from a life-threatening illness into a chronic condition with near-normal life expectancy, with the majority of people living with HIV (PLWH) in the UK expected to be over 50 years of age by 2025 [1]. The synergistic effects of HIV and ageing predispose patients to higher levels of comorbidities at younger ages compared with the general population [2]. Consequently, polypharmacy and medicine-related problems (MRPs) are an important challenge facing older PLWH and their care providers [3-5]. In the general population, older age, multiple comorbidities and polypharmacy are significantly associated with adverse drug events, drug–drug interactions (DDIs) and low adherence to medications [6]. Medicine-related problems also cause greater healthcare resource utilisation, leading to significantly higher healthcare costs [7]. Older PLWH are at particular risk of MRPs because on average they have more comorbidities and are prescribed more medicines than those who are younger or than people who are HIV-negative [8, 9]. Moreover, treatment of PLWH with cART is complex, with significant propensity for MRPs [10]. Medicine-related problems, where medicines are either prescribed inappropriately, or the intended benefits are not realized have also been identified globally as significant contributory factors to medicine-related harm [11, 12], with higher prevalence of preventable medication harm observed in older people [13].

There is extensive evidence in older people with multimorbidity that medicines optimization, including structured medicine (or medication) reviews (SMRs), contributes to reducing the incidence of MRPs [14-17]. Availability of complete medicines lists has been shown to reduce number of DDIs per HIV outpatient [18], and a specialist pharmacist consultation prior to routine HIV outpatient appointments has been shown to increase detection of potential DDIs [19]. Hence medication reviews are one of the medicines optimization tools recommended to reduce the risk of DDIs and other MRPs in PLWH. However, despite the well-documented higher prevalence of DDIs and polypharmacy in PLWH, evidence of the benefits of medication reviews in the HIV outpatient setting is lacking.

We aimed to examine the feasibility and acceptability of a MOR toolkit and the impact of the intervention on health-related quality of life and costs.

METHODS

Study design and participants

We conducted a randomized controlled open trial between January 2018 and December 2019. In total, 200 participants were recruited from four HIV outpatient clinics within the Sussex HIV Network (Brighton, Chichester, Crawley and Worthing). Inclusion criteria were PLWH over 18 years of age prescribed cART, with participants required to be either > 50 years of age or < 50 years with comorbidities for which the participant was prescribed at least one regular medicine. Patients who had received a recent medicines review by an HIV pharmacist as part of their routine care within the previous 6 months were excluded.

Patients were recruited while attending clinic for a routine appointment. Following receipt of participant consent and questionnaire completion, 1:1 block randomization was conducted using Sealed Envelope [20]. One hundred participants were randomized to receive the intervention (a SMR using the MOR toolkit), while 100 controls received standard HIV outpatient pharmaceutical care. Participants in the intervention arm underwent the MOR with an HIV pharmacist within 1 month of consent and again at 6–8 months from consent, with MOR appointments scheduled as close as possible to the participants' routine 6-monthly blood test or medical appointments. Control arm participants received standard pharmaceutical care following their 6-monthly medical appointments.

Intervention

The MOR toolkit was collaboratively developed in 2014 by four UK-based HIV specialist pharmacists, with project management and logistical support from Wave Healthcare Communications, Amersham, Buckinghamshire, England (an independent medical education agency). The initiative was facilitated and funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD) UK (Kenilworth, NJ, USA) and the toolkit is endorsed by the UK HIV Pharmacy Association (HIVPA). The core objective of the toolkit is to enhance patient safety by identifying and reviewing all patients at a higher risk for polypharmacy or DDIs in an HIV outpatient setting. The toolkit comprises a user guide and a supply of two forms: ‘My Clinic Companion’ (Figure S1a) is a patient-orientated questionnaire that promotes self-report of medications and adherence; it can be used both to identify patients who are most likely to benefit from a MOR appointment and to facilitate the SMR. The ‘MOR consultation form’ (Figure S1b) is designed to aid, and provide a record of, the structured patient consultation using information derived directly from the patient and, where necessary, primary care prescribing records and information from local databases (e.g. hospital records). In addition, the ‘MOR consultation form’ identifies any key care providers who may be involved with the patients' healthcare, including prior consent to contact if this is required, and identifies healthcare interventions that may be beneficial to the patient, such as smoking cessation or adherence education. The intervention was delivered by an HIV specialist pharmacist during a pre-booked consultation in a clinic room, with sufficient time to review the patient's medicines (including accessing their Summary Care Record on the NHS spine portal when necessary) and to assess potential MRPs.

Standard of care

An HIV specialist pharmacist conducts a ‘clinical screen’ of the cART prescription in a designated area adjacent to the clinic waiting room before the patient takes it to the hospital outpatient pharmacy for dispensing. This process, which typically takes about 5 min, includes viewing the HIV clinic electronic patient record to verify the drugs and doses prescribed, check relevant blood test results and documented concomitant medications (‘comedications’), as well as asking the patient if they are taking any new medicines or have any questions. The pharmacist often has several patients waiting, as well as dealing with requests for advice from staff and other patients, either in person or by telephone.

Data collection

Demographic and clinical data were recorded for all participants following consent (age, gender, ethnicity, sexuality, age at HIV diagnosis, years on cART, type of cART regimen, current CD4, nadir CD4, HIV RNA viral load, number of comorbidities, and number and type of comedications). The MRPs were categorized as: potential adverse reaction; clinically relevant potential DDI with cART, identified and graded using the University of Liverpool and/or Toronto General Hospital HIV drug interactions references [21, 22]; dose adjustment required (e.g. due to renal impairment); problems with handling or administration; off-label drugs used inappropriately; under-treatment (no prescription for an actual indication according to medical guidelines); and unnecessary drugs which could safely be stopped or simplified. In both study groups, confirmed or suspected adverse reactions were reported or identified during the pharmacist consultation. The duration of the consultation and time spent preparing the pharmacist's report was also recorded, as well as their recommendations (to be resolved by the patient, GP or consultant HIV physician) resulting from the MOR consultation.

Patient and healthcare provider satisfaction

A voluntary self-completed survey was given to participants after the follow-up MOR clinic appointment. The survey asked participants to rate the MOR service provided by the pharmacist and whether they felt more confident managing their medicines after the review. An online questionnaire for healthcare professionals working in the HIV clinics (excluding those providing the MOR service) was accessible from December 2019 to March 2020. This was created and hosted using Online Surveys [23] and distributed via email to HIV clinical staff. Job role, perceived importance of the service and improvement to PLWH care were assessed. Partially completed questionnaires were omitted from analysis.

Intervention costs and health related quality of life

Assessment of health-related quality of life was carried out using the EuroQol five-dimension five-level (EQ-5D-5L) questionnaire using the visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS). The VAS records the respondent's self-rated health from 0 (‘the worst health you can imagine’) to 100 (‘the best health you can imagine’). The intervention was costed from the NHS perspective using the recommended methods for economic evaluations in healthcare [24]. Costs associated with the medication review were estimated based on the times spent by pharmacists on main review activities, including arranging appointment with patients; meetings with patients; checking primary care prescribing (Summary Care Record) via the NHS spine portal; communicating with healthcare professionals with respect to the medication review; producing the medication review report; and any additional relevant documentation (e.g. adverse drug reaction reporting). Data on the time spent on these activities were collected prospectively using a purpose-designed resource use questionnaire (supplementary data: resource use questionnaire). Data collected for each pharmacist included the number of patients with whom they conducted a MOR; the number of MOR-related activities and the time spent on them (average, minimum and maximum time); as well as their pay band and HIV clinic site. Pharmacists' time was calculated using the midpoint salaries of the UK NHS Agenda for Change pay scales 2018–2019 [25]. The intervention costs were calculated per medication review and per patient. Cost ranges were estimated using the maximum and minimum times spent on different review activities.

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint of the study was change in the number of MRPs between the intervention group and the control group at baseline and 6 months. All participants who were enrolled and subsequently baselined into the study formed part of the statistical analysis. All descriptive statistics of the quantitative data are presented with point estimates and indication of variability in data, where hyper-geometric distributed data are presented as medians with interquartile range (IQR), and Gaussian normal data are presented as means with standard deviation. Change in the number of MRPs and EQ-VAS scores between intervention and control groups were calculated using Mann–Whitney. Within-study time point changes from baseline for non-parametric data were analysed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v.9.4 statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and all p-values presented are two-tailed. Although this is a feasibility trial we estimated an average number of four MRPs per patient at baseline and expected a reduction of 0.6% MRP (i.e. 15%) per patient with a standard deviation of 1.5 MRPs, a power of 95%, an α = 5%, and a dropout rate of 5%, resulting in a sample size of 100 participants in each group. Results are presented using the Consort Statement checklist for reporting of clinical trials [26].

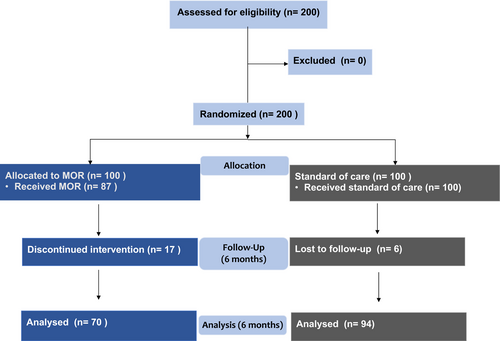

RESULTS

A total of 200 participants were recruited (100 to the intervention group and 100 to the control/standard care group). Most patients (155, 77%) were recruited in Brighton, which has the largest cohort of patients (n = 2500 PLWH). Of the 100 participants allocated to the intervention group, 87 received the MOR at baseline; baseline data were collected for all 100 participants receiving standard care. At 6 months a further 17 patients had withdrawn from the intervention group; six participants from the control group were lost to study follow-up. The main reasons for study discontinuation were patients unable or unwilling to attend a MOR consultation (13 at baseline and an additional 17 at 6 months) and lost to follow-up (six control arm participants at 6 months). A total of 70 participants received their 6-month MOR, with data recorded for 94 standard care participants (Figure 1). No significant differences in baseline characteristics or clinical parameters between study groups were observed (Table 1).

| Characteristic |

MOR (n = 87) |

Standard care (n = 100) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)a | 59.5 (50–78) | 60 (50–82) | NS |

| Male [n (%)] | 76 (87) | 90 (90) | NS |

| Ethnicity [n (%)] | |||

| White | 78 (89) | 92 (92) | NS |

| Black | 8 (9) | 8 (8) | |

| Asian | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Sexuality [n (%)] | |||

| MSM | 66 (75) | 86 (86) | NS |

| Heterosexual | 21 (25) | 14 (14) | |

| Time since HIV diagnosis (years)a | 17 (1–35) | 18 (1–34) | NS |

| Time on ART (years)a | 13 (1–29) | 13 (1–28) | NS |

| HIV-based cART [n (%)] | |||

| PI-based | 27 (31) | 30 (30) | NS |

| INSTI-based | 29 (33) | 29 (29) | |

| NNRTI-based | 31 (35) | 41 (41) | |

| CD4 count (cells/mL)a | 655 (98–1406) | 557 (68–1609) | NS |

| HIV RNA viral load < 40 copies/mL | 95% | 97.7% | |

- Abbreviations: cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; INSTI, integrase inhibitor; MOR, Medicines Management Optimisation Review; MSM, men who have sex with men; NNRTI, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor.

- a Median (interquartile range).

Medication-related problems

A total of 93 MRPs were identified in the intervention group at baseline compared with only two in the standard care group. The median (IQR) numbers of MRP at baseline were 1 (0–6) and 0 (1–2) for the intervention and standard care groups, respectively. This difference was significant (p = 0.001, z = −8.6, r = 0.6). At 6 months a further 33 new MRPs were identified in the intervention group versus three in the control group (p = 0.001, z = −5.7, r = 0.4). There was a significant reduction in the number of new MRPs at 6 months in the intervention group compared with baseline (p = 0.001, Z = −3.7, r = 0.2) (Figure 2). The most common MRPs identified at both time points in the intervention arm were DDIs, followed by need for dose adjustment (including where this was due to a DDI), and potential adverse drug reactions (Table 2).

| MRP type | Day 0 | 6 months (new MRPs) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

MOR (n = 93) |

Standard care (n = 2) |

MOR (n = 33) |

Standard care (n = 3) |

|

| Potential drug–drug interaction | 34 | 1 | 10 | 0 |

| Potentials adverse drug reaction | 14 | 0 | 6 | 2 |

| Dose adjustment | 21 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Problem with handling or administration | 10 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Unnecessarily complex regimen | 4 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Inappropriate off-label use | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Undertreatment | 6 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Other | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Non-ART medications

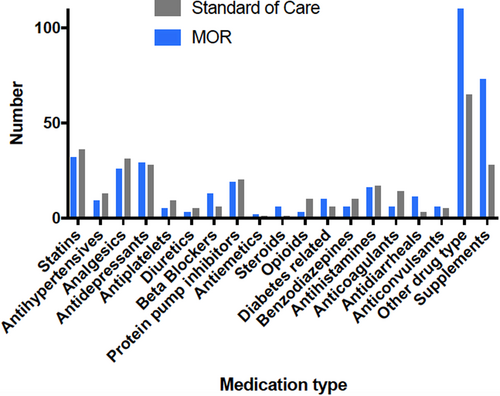

Overall, the median (range) of non-ART medications for both groups was 5 (0–17). At both time points a significantly greater number of non-ART drugs was recorded in the intervention group compared with the standard care group: at baseline [mean (SD) = 7.1 (3.6) vs. 4.5 [27]; p < 0.001, 95% CI: 1.3–3.9] and 6 months [mean (SD) = 6.8 (3.9) vs. 5.2 (0.68); p = 0.7]. Polypharmacy, defined as more than three non-ART medications, was documented in 63% of those in the intervention group compared with 46% in the control group. Although there was a reduction in the number of non-ART medications at 6 months in the intervention group (61 to 45) the difference was not significant (p = 0.217). Figure 3 shows the type of non-ART drugs for both study groups. The main differences between study groups in the type of non-ART drugs documented were nutritional/mineral supplements, topical/injectable testosterone and thyroid replacement therapy.

Pharmacists' recommendations

Medicine-related problems in both study groups generated pharmacist recommendations: patient to resolve, GP to resolve, or HIV physician to resolve. It is not possible to describe in detail all the recommendations given but they included: those for patients to resolve, such as stopping a supplement; those for the GP to resolve, such as adjusting the dose of a non-ART medication; or those for the HIV physician to resolve, such as changing cART regimen when there was no safe alternative to a currently contraindicated non-ART medicine. Pharmacists fully resolved 42 (44%) of all MRPs identified in both study groups at baseline (n = 95) and a further 67 (51%) of the total number of MRPs at 6 months, including those unresolved from baseline (n = 52) and newly identified (n = 36). A total of 22 out of 131 MRPs (17%) remained unresolved at 6 months.

Intervention costs and impact of quality of life

On average, pharmacists spent 69 min on the baseline assessment and 67 min on the follow-up assessment. The average cost of the review was £77 (estimated range £36–£211). Given that not all patients incurred the full review cost included in all activities described previously, the average cost of a MOR intervention, including visit, per patient was £43. The median EQ-VAS score for all participants was 75 (1–100). No significant changes in health-related quality of life EQ-VAS scores between MOR and standard care groups were observed at baseline (p = 0.860, 95% CI: −2.8–10.4) or 6 months (p = 0.896, 95% CI: −8.3–7.1). Similarly, no changes in EQ-VAS scores were observed at 6 months in any of the study groups compared with baseline (MOR, p = 0.646, 95% CI: −3.6–5.7; standard care, p = 0.12, 95% CI: −5.5–0.66).

Patient and healthcare professional satisfaction

Patient satisfaction questionnaires were completed by 38 patients (54%) who attended a MOR. All respondents rated the service provided as excellent or very good. Most respondents strongly agreed that after the MOR consultations they felt more confident in managing their medicines. Healthcare professional questionnaires were completed by nine out of 31 (29%) professionals involved with HIV care (six doctors and three nurses). All respondents found the information provided by the MOR very or somewhat useful – in particular, information about adherence and dosage of other non-ART medications. Overall, healthcare professionals were very satisfied with the service provided.

DISCUSSION

This study provides evidence that the use of targeted MOR consultations within HIV outpatient services is feasible, acceptable and increases the identification of MRPs by specialist pharmacists. The study found a significantly higher number of MRPs were detected using a MOR at both baseline and 6 months, most likely because only those non-ART drugs already documented in the HIV clinic electronic patient record were recorded for the control group, unless patients volunteered new information to the pharmacist when presenting their prescription for clinical review prior to dispensing. Although the study inclusion criteria included younger PLWH with more than one comorbidity, most participants were aged at least 50, and there were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the intervention and control arms. However, not all participants had a comorbidity or were taking any co-medications, so the impact of MRPs may be even greater if targeted at those who would benefit most.

No effect on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was demonstrated, which is consistent with systematic reviews of other SMR interventions [28]. This may reflect a relatively minimal impact of the majority of MRPs on the experiential perception of participants' quality of life, despite the potential for an MRP to cause significant harm. For example, resolving a DDI that reduces statin efficacy confers potential long-term benefit which is unlikely to manifest in any immediate improvement in quality of life. Similarly, if MRPs that reduce antiretroviral exposure are prevented or resolved before cART failure occurs, this is not expected to impact on quality of life. It is also possible that the EQ-5D-5L lacks specificity for the issues facing this particular study population. Although the EQ-5D-5L has been validated for use in HIV populations [29], a ceiling effect has been reported, which may reduce its sensitivity in people who report good baseline HRQoL [30]; in addition, the specific impacts of polypharmacy and comorbidities in an older HIV population may not be reflected adequately in this broad measurement tool.

The higher number of dropouts in the intervention arm (13 before receiving baseline MOR and a further 17 who did not have a MOR at 6 months) probably reflects the additional pharmacist consultations compared with the control arm (standard care), as this could not always be combined with another scheduled clinic attendance (e.g. for a routine blood or medical appointment) due to the capacity constraints of the HIV pharmacy team. Similarly, some participants who had attended a baseline MOR at which no MRPs were identified may not have been motivated to prioritise the 6-month appointment if their medicines were unchanged and they had no new self-perceived MRPs. Contacting participants who cancelled or did not attend to reschedule appointments was an additional administrative burden for the pharmacy team.

This study has several limitations; first, it is a feasibility study and therefore was not powered to assess the intervention's effectiveness. We calculated a sample size based on an a priori estimation of the number of MRPs identified and the reduction of MRPs over time, but we were unable to achieve our target number for the intervention group, and therefore results must be interpreted with caution. Second, as participants were recruited while attending clinic for a routine appointment (which in most cases occurs every 6 months), and pharmacist clinic appointments are not available at the same time as every medical or nurse clinic, many MOR consultations required an additional attendance. If this model was incorporated into standard care, the additional time and expenditure would preclude some patients from having a MOR. However, since the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, different consultation modes have been introduced, including telephone and video consults, which would help to overcome these barriers. We did not have an independent investigator reviewing prescriptions in the standard care group to establish if the lower number of MRPs identified was due to a difference in patient complexity. This was mitigated by all pharmacists at each clinical service (n = 8) reviewing prescriptions for both study groups.

An important limitation of the current study is that the majority of participants were white men who have sex with men, reflecting the demographics of the clinics' cohorts. Consequently, generalizations to other groups cannot be made and further research is needed to examine the efficacy of MORs in different populations. The impact of factors such as economic deprivation on ability or willingness to attend were also not explored in this study. Our estimations of MOR costs were based on pharmacists' time and did not take into account costs associated with MRPs, such as unscheduled consultations, accident and emergency visits and hospitalizations. Cost savings due to reducing unnecessary prescribing is another important economic outcome that was not assessed here. The quantification of these costs was beyond the remit of this study, as this would require a fully powered sample size. Patients' waiting time for consultations in relation to MRPs and associated opportunity costs should also be considered in future economic evaluations. In an increasingly digital age it would be useful to have an electronic version of the MOR toolkit, and service development should include options for telephone, video and in-person consultations.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrated it was feasible and acceptable for HIV pharmacists to conduct SMRs using the MOR toolkit in an HIV outpatient clinic, and that the intervention increased the number of medicine-related problems that were identified and resolved. The MOR consultations were rated highly by patients and provided useful information to other healthcare professionals involved in their care. An increase in HIV pharmacist capacity would be required to integrate MORs into standard care in some, if not all, HIV clinical services. Future work should explore and compare alternative delivery models and care pathways that utilize the skills of HIV pharmacists in secondary care and clinical pharmacists in primary care.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The MOR Toolkit was developed by HIV pharmacists HALD, Neal Marshall, Sonali Sonecha and Adele Torkington, with support from Bryn Jones and James Suares (MSD) and Linda Brown (Wave); it was funded by MSD. Thanks to the HIV pharmacists who participated in the study: Venita Hardweir, Kin Ing, HALD, Su Shin Lim, Dave Moore, Sacha Pires, Claire Richardson, Mark Shaw and Emma Simpkin.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

JHV has received travel and research grants from and has been a speaker/advisor for Merck, Janssen Cilag, Piramal Imaging, ViiV Healthcare and Gilead sciences. HALD has received honoraria and financial support for conference attendance from ViiV Healthcare and Gilead Sciences.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

JHV designed the study and contributed with data analysis and writing the manuscript. HALD was involved with study design and as lead author of the manuscript. KA was involved in patient recruitment and contributed to all manuscript drafts. NH led the cost analyses and contributed to all manuscript drafts. DM and KI were site leads and contributors to all manuscript drafts.