Trends of age-related non-communicable diseases in people living with HIV and comparison with uninfected controls: A nationwide population-based study in South Korea

Funding information

This work was supported by research grants for deriving the major clinical and epidemiological indicators of people with HIV (Korea HIV/AIDS Cohort Study, 2019-ER5101-00), the Research Program funded by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019-ER5408-00), and a grant from the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant no. HI14C1324).

Abstract

Objectives

We aim to compare the trends of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and death among people living with HIV (PLWH) and uninfected controls in South Korea.

Methods

We identified PLWH from a nationwide database of all Korean citizens enrolled from 1 January 2004 to 31 December 2016. A control cohort was randomly selected for PLWH by frequency matching for age and sex in a 20:1 ratio. To compare NCD trends between the groups, adjusted incidence rate ratios for outcomes across ages, calendar years and times after HIV diagnosis were calculated.

Results

We included 14 134 PLWH and 282 039 controls in this study; 58.5% of PLWH and 36.4% of the controls were diagnosed with at least one NCD. The incidence rates of cancers, chronic kidney disease, depression, osteoporosis, diabetes and dyslipidaemia were higher in PLWH than in the controls, whereas those of cardiovascular disease, heart failure, ischaemic stroke and hypertension were lower in PLWH. Relative risks (RRs) for NCDs in PLWH were higher than controls in younger age groups. Trends in the RRs of NCDs tended to increase with the calendar year for PLWH vs. controls and either stabilized or decreased with time after HIV diagnosis. The RR of death from PLWH has decreased with the calendar year, but showed a tendency to rise again after 2014 and was significant at the early stage of HIV diagnosis.

Conclusions

Although the RR of each NCD in PLWH showed variable trends compared with that in controls, NCDs in PLWH have been increasingly prevalent.

INTRODUCTION

Due to the advancement of effective antiretroviral therapy (ART), people living with HIV (PLWH) have higher life expectancies. In South Korea, > 35% of all PLWH were over 50 years old by 2017, and this proportion is expected to increase in the future [1]. As a result, there has been an increased interest in age-related non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in PLWH, leading to several nationwide HIV cohort studies investigating the association between HIV infection and the risk of age-related NCDs such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), stroke, cancers and osteoporotic fractures [2-5]. These studies have concluded that HIV infections possibly increase the risk of age-related NCDs as a result of persistent low-grade inflammation, HIV-induced chronic immune activation and potentially accelerated ageing [6]. Thus, the risk of NCDs might increase not only with age, but also with the duration of HIV infection and administration of ART, independent of age [5]. However, most studies have been conducted in western regions such as the United States and Europe, and data on the time trends of NCDs in Asia are still lacking [7]. Very little data comparing the incidence of NCDs between PLWH and HIV-uninfected populations are available [8]. In South Korea, the history of HIV infection is not extensive, but unlike the global trend, the number of newly diagnosed HIV infections is still increasing [1]. As medical fees related to HIV infection are fully reimbursed in Korea, treatment compliance is high and the average life expectancy for PLWH is also increasing [9]. Thus, data on the current status and time trends of age-related NCDs in Korea are indispensable. This study aimed to compare the characteristics and time trends of NCDs between PLWH and uninfected individuals in Korea using the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) claim database, which covers the entire population.

METHODS

Data sources

We used data from the NHIS claims database and death certificates from Statistics Korea. In Korea, national health insurance is mandatory and claims-based data including diagnosis and treatment were collected for all individuals covered by the NHIS [10]. The NHIS data included the participants' identifier, birth date, sex, type of health insurance, income, residence, date of death, medical utilization records containing their specific diagnosis, treatment information such as prescription drugs, procedure codes and the medical costs covered [11]. Detailed diagnoses were coded using the Korean Classification of Disease (KCD), which is based on the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification. The data also included the specialized claim codes for the National Health Insurance's expanded benefit coverage service, which guarantees coverage for 90% of the medical cost for patients with severe or rare incurable diseases, including HIV infection [12]. Most diagnoses are included in the insurance claims, and clinicians should enter an appropriate diagnosis code for reimbursement for the claim. If clinicians enter the wrong diagnosis, the claim is refused according to the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service's assessment evaluation [13]. Thus, it is assumed that the entered diagnostic code is reliable and extensive research has been conducted on this subject in Korea [14, 15].

Study population

We identified newly diagnosed PLWH with the appropriate diagnosis codes (KCD-7 codes for HIV infection: B20-24, O98.7, Z21) from 1 January 2004 to 31 December 2016. To improve the validity of the diagnosis, we included patients with the specialized claim code of V103 for the expanded benefit coverage, which is qualified by the NHIS every 5 years. A record was created for each day of follow-up, and the baseline date was defined as the date listed on the specialized claim code for HIV infection. An individual with AIDS was defined as an individual with at least one diagnosis of an AIDS-defining illness, as defined by the Centers for Disease Control [9]. Twenty controls were randomly selected for each PLWH annually, by frequency matching for age and sex using the Korean resident registration number (a unique identification number) as a reference cohort. Because South Korea, in which this study was conducted, does not have a large land territory or major differences in racial identity and because region climates and environments, as well as dietary factors, are similar across the nation, matching for separate race and region was not made [16]. Finally, 282 039 controls were matched to 14 134 PLWH from 2004 to 2016 at a ratio of 20:1. We calculated age at the date of entry into each cohort in that specific calendar year. For validation, we compared the number of individuals included under these conditions with the official number of those diagnosed with HIV infections published by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) and concluded that the conditions we set were valid for defining PLWH (Table 1). The numbers of HIV infections using other operational definitions were also compared with the officially reported numbers, and we concluded that the definition in this study did not include uninfected cases and had the highest coverage. The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) at Yonsei University Health System Clinical Trial Center (IRB number: 4-2017-1072). The informed consent of the participants was waived by the IRB because of the pure observational nature of the study.

| Years | Defined by diagnosis codes including the specialized claim code | Officially reported by Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 515 | 763 |

| 2005 | 726 | 734 |

| 2006 | 767 | 796 |

| 2007 | 743 | 828 |

| 2008 | 773 | 900 |

| 2009 | 766 | 839 |

| 2010 | 836 | 837 |

| 2011 | 915 | 959 |

| 2012 | 869 | 953 |

| 2013 | 1057 | 1114 |

| 2014 | 1149 | 1191 |

| 2015 | 1102 | 1152 |

| 2016 | 1167 | 1199 |

- Values are the number of patients.

Wash-out period and follow-up

In order to define the incidence of NCDs precisely, those who already had a diagnostic code for an NCD 2 years prior to the start of the study period (1 January 2002 to 31 December 2003) were excluded to eliminate cases of pre-existing NCDs [17]. During follow-up, the index date was defined as the first date of the occurrence of an NCD. Each individual was followed until the index date, date of death or the end of the study period (31 December 2016), whichever came first.

Outcome definitions

Non-communicable diseases were classified as follows: cancers including virus- and smoking-associated cancers, CVD, heart failure, hypertension, ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke, chronic kidney disease (CKD) including end-stage renal disease, chronic liver disease unrelated to a virus, depression, neurocognitive disorders, osteoporosis, diabetes and dyslipidaemia. The NCDs were defined according to the KCD codes (Table S1). The incidence of NCDs was defined as having made two visits to the outpatient clinic or the first hospitalization for NCDs, in order to guarantee the validity of the diagnosis [18, 19].

Statistical analysis

The incidence rates of NCDs were presented as the number of events per 1000 person-years. To assess trends in relative risk (RR) across ages, calendar years and time after HIV diagnosis, we calculated adjusted incidence rate ratios (aIRRs) comparing individuals with and without HIV infection for all NCDs and death. The aIRRs and confidence intervals (CIs) for the two groups were estimated using the GenMod procedure with modified Poisson regression models adjusted for age, sex, calendar year and year of study enrolment. To adjust for covariates in the estimation of the aIRR, a log-binomial regression model can be used. When the outcome is rare and the sample size is large, a Poisson regression model can be used because a Poisson distribution approximates the binomial distribution well. A modified Poisson method with robust error variance was proposed to estimate the RR with 95% CIs with the correct coverage. Using SAS, the robust error variances can be obtained by using the subject identifier. A P-value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were performed in SAS v.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) or were conducted using R statistical software, v.3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics and the overall incidence of NCDs in the study population

Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics and overall incidence of NCDs in the study population. A total of 14 134 PLWH and 282 039 age- and sex-matched controls were included. In both cohorts, the proportion of individuals older than 50 years was 23.4%, and 90.6% were men. Overall, 8262 (58.5%) PLWH and 102 680 (36.4%) of the individuals in the control cohort were diagnosed with at least one NCD. The incidences of virus-associated cancers, CKD, osteoporosis, diabetes and dyslipidaemia were higher in PLWH than in the control cohort. By contrast, the incidences of CVD, heart failure, hypertension, and ischemic stroke were lower in PLWH than in the control cohort. Meanwhile, there was no statistically significant difference between PLWH and uninfected controls in household income (Table S2).

|

People living with HIV [n (%)] |

Control cohort [n (%)] |

Difference of incidence (P-value*) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of individuals | 14 134 | 282 039 | |

| Men | 12 841 (90.6) | 256 781 (90.6) | > 0.999 |

| Age (years) | > 0.999 | ||

| < 40 | 7533 (53.1) | 150 553 (53.1) | |

| 40–49 | 3334 (23.5) | 66 658 (23.5) | |

| 50–59 | 2110 (14.9) | 42 193 (14.9) | |

| 60–69 | 887 (6.3) | 17 737 (6.3) | |

| ≥ 70 | 312 (2.2) | 6233 (2.2) | |

| AIDS | 4005 (28.3) | – | |

| Death | 1545 (10.9) | 5258 (1.9) | < 0.001 |

| All cancers | 614 (4.3) | 7710 (2.7) | < 0.001 |

| Virus-associated cancers | 378 (2.7) | 931 (0.3) | < 0.001 |

| Smoking-associated cancers | 74 (0.5) | 1537 (0.5) | 0.815 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 198 (1.4) | 8609 (3.1) | < 0.001 |

| Heart failure | 62 (0.4) | 3412 (1.2) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1053 (7.5) | 47 496 (16.8) | < 0.001 |

| Ischemic stroke | 264 (1.9) | 9223 (3.3) | < 0.001 |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 45 (0.3) | 1169 (0.4) | 0.091 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 99 (0.7) | 1343 (0.5) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic liver disease | 104 (0.7) | 2351 (0.8) | 0.234 |

| Depression | 501 (3.5) | 10 200 (3.6) | 0.678 |

| Neurocognitive disorder | 120 (0.9) | 3155 (1.1) | 0.002 |

| Osteoporosis | 1139 (8.1) | 4745 (1.7) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1464 (10.4) | 18 535 (6.6) | < 0.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 6383 (45.2) | 36 849 (13.1) | < 0.001 |

- * P-values were calculated using the χ² test.

Comparison of the incidence of NCDs across age groups between PLWH and the control cohort

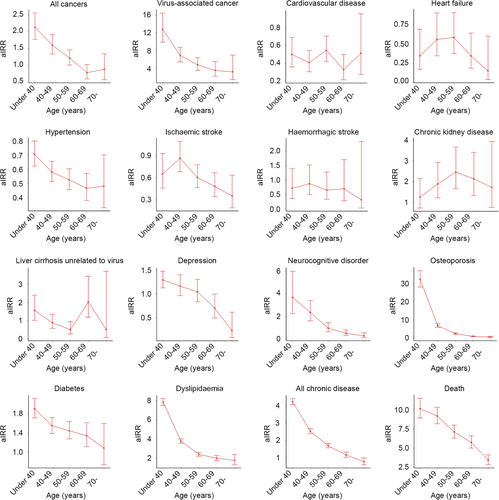

Figure 1 shows the aIRR for NCDs among PLWH and the controls according to their ages. In general, the incidence of NCDs was found to be higher in PLWH than in controls when individuals were younger. At older ages, the aIRR of NCDs tended to decrease. However, in those diagnosed with CKD, an increase in the incidence was observed with an increase in age.

Trends in NCDs across calendar years

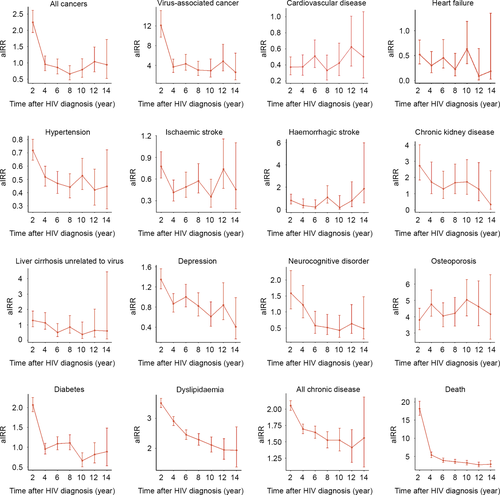

The trends in age-standardized aIRRs for NCDs with calendar years are shown in Fig. 2. Compared with the controls, PLWH with CVD, heart failure, hypertension and ischaemic stroke showed consistently low aIRRs across calendar years. By contrast, trends in the aIRRs of other NCDs for PLWH vs. controls tended to increase with the calendar year, and those were particularly pronounced in CKD, osteoporosis and dyslipidaemia (Table S3).

Trends in NCDs with time after HIV diagnosis

The aIRRs for NCDs in PLWH compared with the controls varied for each disease over the time after HIV diagnosis. The age-standardized risk of virus-associated cancer in PLWH was significantly higher at the initial stage of HIV diagnosis than in the controls. The aIRRs of CKD, depression, diabetes and dyslipidaemia tended to decrease with time from HIV diagnosis in PLWH compared with the controls, but in the case of CVD or osteoporosis, aIRR trends were either relatively stable or increasing (Fig. 3; Table S4).

Trends in mortality in PLWH and the control cohort

During the follow-up period, 1545 (10.9%) PLWH died, while 5258 (1.9%) controls died. The aIRR for death was higher in the PLWH across all ages compared with the control cohorts, especially higher with younger ages (Fig. 1). Compared with that in the control cohort, the aIRR of death in PLWH showed a decreasing trend over the calendar years after 2004, but increased again after 2014 (Fig. 2; Table S3). Meanwhile, the aIRR for death in PLWH was significantly higher at the early stage of HIV diagnosis and remained higher, but decreased as the duration of time after HIV diagnosis increased (Fig. 3; Table S4).

DISCUSSION

We compared the aIRRs for NCDs among PLWH and the control cohort, in terms of the patients' ages, the calendar year and the time after HIV diagnosis, to identify NCDs trends in PLWH. We identified several features that differed from those reported in studies conducted in other countries [5, 20].

In this study, the incidence rates of CVD, heart failure, hypertension and ischaemic stroke were lower in PLWH than in the control cohort, regardless of the patients' ages, calendar year and the time after HIV diagnosis. The incidence rates of CVD, hypertension and ischaemic stroke were similar to those reported in a previous study conducted in Korea [21]. According to a study published using the Korean HIV/AIDS Cohort database, which consists of data from 19 hospitals in Korea, the proportion of PLWH on antihypertensive treatment was 8.9%, the prevalence of ischaemic stroke was 1.1%, and the prevalence of angina pectoris and myocardial infarction were both 0.3%, respectively [21]. Therefore, considering the results of the two studies, which examined PLWH through nationwide population-based data and utilized hospital data through multi-centre cohorts, we concluded that CVD, hypertension and ischaemic stroke actually occurred less in PLWH than in age- and sex-matched controls in Korea. This is different from the results of studies conducted in other countries [5, 20]. One reason for this finding is that in contrast to those in Denmark, there are very few intravenous drug users (IDUs) among PLWH in Korea. Rasmussen et al. [22] reported that being classified as an IDU is a risk factor for the development of cerebrovascular events in HIV-infected individuals in Denmark. They also reported that IDUs accounted for 10.7% of all PLWH, while HIV infection by IDU is rarely reported in Korea. Considering that intravenous drug use is a major cause of vascular complications in PLWH, the low levels of HIV infection caused by IDU in Korea is one of the possible causes of the low incidence of complications such as CVD and ischaemic stroke in PLWH. Additionally, the body mass index (BMI) of PLWH in Korea is lower than that of the uninfected controls. According to the results of the Korean HIV/AIDS Cohort database, 92.8% of Korean PLWH were men, their median BMI was 22.2 kg/m2, and the proportion of those with a BMI > 25 kg/m2 was 16.4% [21]. On the other hand, the results of a BMI survey conducted among Korean adult men indicated that the mean BMI was 24.0 kg/m2, and the proportion of those with a BMI > 25 kg/m2 was 34.9% [23]. As high BMI is known to be a risk factor for hypertension and vascular complications, low BMI among PLWH might be a cause of the low incidence of hypertension and vascular complications in this population [24]. PLWH also visit clinics regularly for medical care; therefore, a possible hypothesis could be that even if they have a high incidence of metabolic complications such as diabetes, it may not lead to fatal outcomes, such as myocardial infarction or ischaemic stroke. Another possible reason for this is that the history of HIV infection in Korea is not extensive, with many people being diagnosed with HIV infection only in recent years as shown in Table 1. In Korea, HIV infection occurred for the first time in 1985; since 1995, more than 100 cases have occurred annually and there have been more than 1000 new cases reported annually from 2013 onwards [1]. As the proportion of those diagnosed with HIV infection was high at those times, it is possible that NCDs may not have occurred yet. As the incidence of NCDs in PLWH has increased over years, there is a possibility that these diseases will occur more frequently in PLWH than in the control cohort in the future, similar to the results from other cohorts.

Virus-associated cancers, CKD, osteoporosis, diabetes and dyslipidaemia were associated with a higher aIRR in PLWH than in the control cohort. This is consistent with results from previous studies [3, 4, 25, 26]. In the case of CKD, the aIRR was higher in the early stage of HIV infection in PLWH, and the aIRR tended to decline with an increase in the time after HIV diagnosis, which is consistent with results from previous studies indicating that ART reduces the risk of developing renal disease [25]. The high incidence of osteoporosis in PLWH is considered to be due to the effects of low BMI, ART and chronic inflammation, as previously known [27]. Meanwhile, despite the fact that PLWH had a lower BMI than the controls, as mentioned earlier, the high risk of diabetes and dyslipidaemia should be considered in relation to many factors, including ART. Although the aetiology of these complications in PLWH specifically was not entirely clear, studies have shown that receiving ART increased the risk of diabetes in PLWH [26, 28]. Moure et al. [29] reported the effects of ART on the fibroblast growth factor 21/β-Klotho System and suggested a mechanism for the association between metabolic complication and ART. It is well known that a protease inhibitor (PI)-based regimen affects the increased incidence of diabetes and dyslipidaemia [30]. Therefore, the use of a PI-based regimen may have influenced the study results. To verify this, we analysed drug use data for PLWH treated at a tertiary hospital in Seoul, South Korea, with follow-up data from more than 600 PLWH. As shown in Fig. S1, we discovered that a PI-based regimen was used most during the study period. Due to the cumulative effect of this, it is thought that the prevalence of diabetes and dyslipidaemia would be higher in the PLWH than in the uninfected controls, despite the low BMI values. In a study focusing on ART compliance among PLWH in Korea, 70.4% of PLWH were found to have treatment compliance of 95% or more [9]. Although this did not meet the UNAIDS target of 90%, it was considered better than the treatment compliance in other countries [31, 32]. Paradoxically, good compliance to ART might be a reason for the higher aIRRs for diabetes and dyslipidaemia in PLWH, even though the BMIs of PLWH were lower than those of the control cohort. Meanwhile, in South Korea, the use of an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI)-based regimen has been increasing in recent years (Fig. S1). However, as this study analysed data up to 2016, evaluation of the effect of the change from a PI-based regimen to an INSTI-based regimen on metabolic profiles, such as dyslipidaemia, was limited.

The aIRRs for most chronic NCDs in PLWH showed a tendency to increase relative to those of the control cohort over the calendar years. In particular, the incidence rates of CKD, osteoporosis and dyslipidaemia have increased rapidly since 2014. This might be due to an increase in the actual incidence of the disease, along with an increase in diagnosis rates by physicians who were more aware of the importance of NCDs in PLWH and performed diagnostic tests. In particular, as side effects were known, such as decreased glomerular filtration rate and loss of bone mineral density, caused by tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), which was used as the preferred nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor backbone from the 2013 national guidelines, it is believed that physicians were more actively performing diagnostic tests for this [33-35]. Therefore, more diagnoses of the disease may have been made. In fact, in South Korea, as the use of TDF has increased and the risk of osteoporosis caused by its use in PLWH has become more widely known, it was recommended in the 2013 national guidelines that men over 50 years of age or menopausal women among PLWH should consider undergoing a bone mineral density test at the initial visit (Fig. S2) [35]. The need to increase interest in NCDs, including dyslipidaemia, has been included since the 2015 national guidelines, and this is thought to have contributed to more active screening [36]. The increased alertness surrounding NCDs in PLWH is of great importance for sustained and appropriate treatment. Roerink et al. [37] reported that even if NCDs such as diabetes were diagnosed in PLWH, screening for microvascular complications such as ophthalmology examinations was rarely performed. Therefore, physicians treating PLWH should not only diagnose NCDs like diabetes, but also be aware of their complications.

Unlike the association with calendar years, the aIRRs for NCDs in PLWH compared with the control cohort were high at the time of HIV diagnosis. Similar to the findings reported in other studies, this tendency was most pronounced for virus-associated cancers [5]. One reason for this was that when individuals were diagnosed with HIV infection, they were tested not only for HIV itself but also for accompanying complications. Therefore, the incidence of NCDs tended to be significant at the stage of HIV diagnosis. This is also related to the fact that NCDs tended to have a higher incidence in PLWH than in controls in younger age groups. Meanwhile, as many individuals were diagnosed with HIV infection in recent years, the time after HIV diagnosis was not long in the case of these study subjects. It is possible that the interpretation of the results could be biased as a result of this. Therefore, further follow-up is needed in the future.

It is well known that individuals with HIV infection continue to have high mortality despite the availability of effective ART [38]. In this study, the aIRR for death was higher in PLWH than in the control cohort regardless of the patients' ages, the calendar year and the time from HIV diagnosis. In particular, the aIRR for death was high at the initial stage of diagnosis of HIV infection, which might be due to the high rate of diagnosis at advanced stages of infection, such as AIDS, which was verified in annually published official reports from the KCDC (Fig. S3). Considering that approximately 30% of PLWH have a history of AIDS, more vigorous efforts are needed to diagnose HIV earlier and maintain appropriate treatment. Compared with controls, the aIRR for death in PLWH was higher in 2004; although it declined thereafter, it rose again after 2014. Jung et al. [39] reported that non-AIDS-associated deaths were increasingly indicated as the main cause of death in PLWH in developed countries including Korea over the calendar year. The recent increase in the aIRR for death in PLWH compared with controls in this study might be attributed to an increase in non-AIDS-associated deaths due to NCDs as well as an increase in diagnoses in the advanced stages. Further studies are needed to follow up on mortality trends comparing PLWH and controls in the future.

Our study has several limitations. First, the present study was conducted based on the reimbursement claims databases from the NHIS. All variables and outcomes were extracted from the electronic database; therefore, precise reviews of clinical presentations such as viral loads or CD4 T-cell counts and modes of transmission, as well as smoking and alcohol consumption, were not available. To overcome these limitations, we utilized diagnostic codes such as the AIDS-defining illness code to define AIDS in the study population. Second, there were some differences in the numbers of new HIV infections between our study and the official report from the KCDC. Although our definition covered 92.8% of the officially reported cases while preventing uninfected cases from being included in the study, some cases were excluded because they did not correspond to our definition, and therefore, we could not evaluate their impact on our results. However, after comparing several other definitions, we decided to use the definition with the specialized claim code because it provided the results with the least likelihood for error. Third, there is a possibility that the diagnosis classification was incorrect due to limitations in the data acquisition method described earlier. However, in Korea, as all HIV-related medical care is fully reimbursed, we assumed that medical care regarding NCDs in PLWH was fully recorded in the database. Additionally, the reliability of this study's results was validated through comparisons with the results of previous studies using data from the Korean HIV/AIDS Cohort database. Fourth, it is possible a healthy survivor effect was introduced; we excluded individuals who were diagnosed with NCDs before the date of inclusion. However, the proportion of these patients was low; therefore, it is possible that this did not affect the study's outcomes. Fifth, PLWH might have been diagnosed earlier with NCD, because they generally seek healthcare more regularly than uninfected controls. As shown in Table S5, this may have contributed to the higher incidence of NCD in PLWH than in uninfected controls, as PLWH undergo tests for NCD more often than uninfected controls according to guidelines [40]. However, considering the high incidences of hypertension and CVD in uninfected controls, that alone cannot explain the tendency for a high incidence of NCD in PLWH. Sixth, variables such as haemorrhagic stroke had a small number of occurrences, leading to a wide CI. The last limitation of our study is that we were not able to prove a causal relationship among the variables included in the study, including the cause of death. Therefore, further studies on causality among the studied variables are needed.

CONCLUSIONS

The incidence rates of cancers, CKD, osteoporosis, diabetes and dyslipidaemia were higher in PLWH than in the control cohort, whereas the incidence rates of CVD, heart failure, hypertension and ischaemic stroke were lower in PLWH than in the control cohort in Korea. With the increasing prevalence and elevated occurrence of NCDs in PLWH in recent years, particularly in younger individuals, physicians treating PLWH ought to be aware of these trends.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

CK and JYC were responsible for the study conceptualization and design. JN analysed the data. JHK, JN, and WK provided statistical expertise. JHK, WK, HS, JunHK, WJL, YB, YS, YC, SA, YL and JYC were involved in the interpretation of the data. JHK and JN drafted the report. JYA, SJS, NSK, J-SY, CK, and JYC participated in the revision of the report for important intellectual content. JHK, JN, WK, HS, JunHK, WJL, YB, YS, YC, SA, YL, JYA, SJS, NSK, J-SY, CK, and JYC were responsible for the final approval of the report. JHK, JN and CK provided the study materials or patients. JYC was responsible for obtaining the funding.