Prevalence and incidence of pre-diabetes and diabetes mellitus among people living with HIV in Ghana: Evidence from the EVERLAST Study

Abstract

Background

Available data from high-income countries suggest that people living with HIV (PLWH) have a four-fold higher risk of diabetes compared with HIV-negative people. In sub-Saharan Africa, with 80% of the global burden of HIV, there is a relative paucity of data on the burden and determinants of prevalent and incident dysglycaemia.

Objectives

To assess the prevalence and incidence of pre-diabetes (pre-DM) and overt diabetes mellitus (DM) among PLWH in a Ghanaian tertiary medical centre.

Methods

We first performed a cross-sectional comparative analytical study involving PLWH on combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) (n = 258), PLWH not on cART (n = 244) and HIV-negative individuals (n = 242). Diabetes, pre-DM and normoglycaemia were defined as haemoglobin A1C (HBA1c) > 6.5%, in the range 5.7–6.4% and < 5.7% respectively. We then prospectively followed up the PLWH for 12 months to assess rates of new-onset DM, and composite of new-onset DM and pre-DM. Multivariate logistic regression models were fitted to identify factors associated with dysglycaemia among PLWH.

Results

The frequencies of DM among PLWH on cART, PLWH not on cART and HIV-negative individuals were 7.4%, 6.6% and 7.4% (P = 0.91), respectively, while pre-DM prevalence rates were 13.2%, 27.9% and 27.3%, respectively (P < 0.0001). Prevalent DM was independently associated with increasing age [adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) (aOR, 95% CI) = 1.82 (1.20–2.77) for each 10-year rise], male sex [aOR = 2.64 (1.20–5.80)] and log(triglyceride/HDL cholesterol) [aOR = 8.54 (2.53–28.83)]. Prevalent pre-DM was independently associated with being on cART [aOR (95% CI) = 0.35 (0.18–0.69)]. There were a total of 12 cases of incident DM over 359.25 person-years, giving 33.4/1000 person-years of follow-up (PYFU) (95% CI: 18.1–56.8/1000), and an rate of incident pre-DM of 212.7/1000 PYFU (95 CI: 164.5–270.9/1000). The two independent factors associated with new-onset DM were having pre-DM at enrolment [aOR = 6.27 (1.89–20.81)] and being established on cART at enrolment [aOR = 12.02 (1.48–97.70)].

Conclusions

Incidence rates of pre-DM and overt DM among Ghanaian PLWH on cART ranks among the highest in the literature. There is an urgent need for routine screening and a multidisciplinary approach to cardiovascular disease risk reduction among PLWH to reduce morbidity and mortality from the detrimental effects of dysglycaemia.

Introduction

The widespread introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) has led to significant reductions in HIV mortality and morbidity from opportunistic infections and AIDS-related malignancies among people living with HIV (PLWH). While, on the one hand, the success of cART has led to increased life expectancy, on the other, PLWH are now at a higher risk of non-communicable diseases, notably cardiovascular diseases [1, 2. Available data from the United States suggest that PLWH are at a four-fold higher risk for diabetes mellitus (DM) than HIV-negative persons [3, 4. In addition, pre-diabetes mellitus (Pre-DM), which is characterized by increased impairment in fasting blood glucose (FBG) or impaired glucose tolerance, appears to be higher among PLWH [5. The heightened risk of dysglycaemic states in PLWH is due to an admixture of chronic inflammation, impact of specific ART agents on glucose metabolism, increasing age and clustering of cardio-metabolic risk factors [6, 7.

In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) with 80% of the global burden of HIV, the prevalence rates of type 2 DM and pre-DM in a systematic review were in the ranges 1–26% and 19–47%, respectively [8. The incidence rate of DM among PLWH in SSA has been reported to vary between 4 and 59 per 1000 follow-up years [9. There are no reported studies among PLWH on incidence rates of pre-DM, a harbinger of DM and an independent predictor of adverse cardiovascular events. The population of PLWH in SSA has unique sociodemographic and clinicopathological profiles, differentiating them from those in high-income countries. These include a relatively younger age of HIV diagnosis, a preponderance of female HIV population, a higher level of inflammatory biomarkers, ongoing use of older thymidine analogue associated with development of dysglycaemia and lipodystrophy [10, 11. In addition, there is a rising burden of obesity in the general population with implications on incidence of cardio-metabolic risk factors such as dysglycaemia, hypertension and dyslipidaemia [12, 13. The astronomic rise in cardiovascular disease (CVD) burden on the African continent coupled with high infectious disease burden, such as HIV, imposes a considerable burden on the fragile health systems and developing economies in this region [14. Contemporary data on the rising burden of CVDs such as type 2 DM among PLWH, in particular, are needed to understand its determinants and propose solutions to address this double burden of disease [15.

Thus our objectives for the present study were, first, to comparatively assess the prevalence and factors associated with dysglycaemic states (pre-DM and type 2 DM) among PLWH on cART, PLWH who are cART-naïve and HIV-negative controls in a cross-sectional fashion. We next sought to determine the predictors of new-onset DM and dysglycaemia (a composite of pre-DM and DM) among PLWH who were either established on cART or initiated on cART in a prospective fashion in a tertiary medical centre in Ghana.

Methods

Study design and population

The Evaluation of Vascular Event Risk while on Long-term Anti-retroviral Suppressive Therapy (EVERLAST) Study is designed as a case–control study to compare CVD risk by assessing for the presence of the major traditional vascular risk factors among Ghanaian PLWH on cART compared with age- and sex-matched PLWH who are cART-naïve and HIV-negative controls [16, 17. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology Committee of Human Research Publications and Ethics. Cases were PLWH aged ≥ 30 years receiving cART for at least 1 year at the HIV clinic of the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital, a tertiary medical facility in Kumasi, Ghana. We consecutively enrolled PLWH aged ≥ 30 years who were cART-naïve at the HIV clinic matched by sex and age band of ± 5 years as well as HIV-negative controls from the community. The PLWH group (cART exposed and cART-naïve) were followed up for 12 months. All participants provided written informed consent.

Study evaluations

A standardized data collection form was developed to collect information on sociodemographic characteristics, including age, sex, educational status and location of residence (rural, peri-urban and urban). Among the PLWH, we collected data through interview and review of medical record chart extraction on HIV disease characteristics, such as current CD4 cell count, HIV-1 viral load, past and current history of cART, and duration on cART. We assessed the traditional vascular risk factors using history-taking and physical examination, and by collecting blood samples for measurement of haemoglobin A1C (HBA1c), FBG and lipid profile [total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and triglycerides].

Prospective follow-up

People living with HIV on cART and those who were cART-naïve at enrolment were prospectively followed up for 12 months via clinic visits every 3 months. During the follow-up period, participants who were cART-naïve at enrolment were subsequently commenced on cART. Anthropometric measurements such as waist and hip circumference and blood pressure were measured at each clinic visit. In addition, glycated haemoglobin measurements and FBG measurements were performed again at months 6 and 12.

The following definitions were used for the traditional vascular risk factors:

- Dysglycaemic status was determined using the American Diabetes Association criteria [18. DM was defined as a history of DM, use of medications for DM, an elevated HBA1c ≥ 6.5% or two FBG readings ≥ 7.0 mmol/L. Euglycaemia/normoglycaemia was defined as HBA1c < 5.7% or FBG < 5.6 mmol/L. Pre-DM/impaired glucose tolerance was defined as HBA1c in the range 5.7–6.4% or two FBG readings of 5.6–7.0 mmol/L.

- Blood pressure (BP) (mean of three measurements) of each study participant was recorded following a standard protocol. A cut-off of at least 140/90 mmHg according to WHO definitions [19 or use of antihypertensive drugs was regarded as an indicator of hypertension.

- Dyslipidaemia was defined as a fasting total cholesterol concentration of ≥ 5.2 mmol/L, HDL cholesterol ≤ 1.03 mmol/L, LDL cholesterol ≥ 3.4 mmol/L, or serum triglyceride ≥ 1.7mmol/L, according to National Cholesterol Education Program guidelines [20.

- Obesity was defined using the WHO guidelines with a waist-to-Hip ratio (WHR) cut-off of 0.90 (for men) and 0.85 (for women) or body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 for obesity [21. WHR was used to assess burden of central adiposity and BMI was used to further categorize participants into underweight, ideal weight, overweight and obese.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of demographic, lifestyle and vascular risk factors, as well as glycaemic status among three groups (normoglycaemia, pre-DM and DM) were performed using anova for continuous parametric variables and χ2 tests for discrete variables. Factors associated with pre-DM, DM and dysglycaemia (combined pre-DM and DM) at baseline were assessed for PLWH regardless of cART status using bivariable and multivariable logistic regression models. Putative factors in models included demographic variables such as age, sex and location of residence; anthropometric measures such as waist-to-hip ratio; traditional vascular risk factors such as lipid subfractions (i.e. total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and triglycerides); HIV-related factors such as WHO clinical status; and CD4 counts. Factors with a P-value ≤ 0.05 at the bivariate level of analysis were included in a multivariable model. Crude incidence rates of DM and pre-DM during follow-up were calculated and expressed as events/1000 person-years of follow-up (PYFU) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) calculated using the mid-P exact test. In all analyses, a P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 7 and SPSS version 21.

Results

Prevalence of pre-DM and DM across the three study groups

The study sample comprised three groups, namely PLWH on cART (n = 258), PLWH who were cART-naïve (n = 244) and HIV-negative adults (n = 242). Only seven PLWH on cART (2.7%), eight PLWH who were cART-naïve (3.3%) and five HIV-negative adults (2.1%) were previously diagnosed with DM and were receiving anti-glycaemic treatment at enrolment. The prevalence of DM across the three groups, classified using combination of previous DM diagnosis and HBA1c, was 7.4% (95% CI: 4.5–11.3%) among PLWH on cART, 6.6% (95% CI: 3.8–10.4%) among cART-naïve PLWH and 6.6% (3.8–10.6%) among HIV-negative controls (P = 0.93). The frequencies of pre-DM across the three groups were 13.6%, (95% CI: 9.6–18.4%), 27.5% (22.0–33.5%) and 26.6% (21.1–32.6%) among PLWH on cART, cART-naïve PLWH and HIV-negative controls, respectively (P < 0.0001). Overall, as a PLWH group, the prevalence of DM was 7.0% and of pre-DM was 20.3% using HBA1c data and medical history. (Table 1).

|

PLWH on cART (N = 258) |

cART-naïve PLWH (N = 244) |

HIV-negative controls (N = 242) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical history of DM [n (%)] | 7 (2.7) | 8 (3.3) | 5 (2.1) | 0.71 |

| Medical history plus HBA1c > 6.5% for diagnosis of DM [n (%)] | 19 (7.4) | 16 (6.6) | 16 (6.6) | 0.93 |

| HBA1c 5.7-6.4% (pre-DM) [n (%)] | 35 (13.6) | 67 (27.5) | 64 (26.6) | < 0.0001 |

| HBA1c < 5.7% (normoglycaemia) [n (%)] | 204 (79.0) | 161 (65.9) | 162 (66.8) | 0.002 |

| 0.002 | ||||

| Medical history plus FBG > 7.0 mmol/L for diagnosis of DM [n (%)] | 30 (11.6) | 38 (15.6) | 56 (23.4) | |

| FBG 5.6–7.0 mmol/L, (pre-DM) [n (%)] | 137 (53.1) | 104 (42.6) | 97 (40.6) | |

| FBG < 5.6 mmol/L (normoglycaemia) [n (%)] | 91 (35.3) | 102 (41.8) | 86 (36.0) |

- PLWH, people living with HIV; cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; HbA1c, haemoglobin A1C; FBG, fasting blood glucose.

Based on FBG data and previous diagnosis of DM, proportions with DM, pre-DM and normoglycaemia were 30 (11.6%), 137 (53.1%), and 91 (35.3%) for PLWH on cART; 38 (15.6%), 104 (42.6%), and 102 (41.8%) for PLWH who were cART-naïve; and 56 (23.4%), 97 (40.6%), and 86 (36.0%) for HIV-negative controls (P = 0.002). Compositely among PLWH the prevalence of DM was 13.5%, that of pre-DM was 48.0% and that of normoglycaemia was 38.4% based on FBG values. The kappa-statistic test for agreement of classification of glycaemic status using HBA1c and FBG tests was 0.11 (95% CI: 0.06–0.17), indicating poor agreement.

Characteristics of people living with HIV according glycaemic status at enrolment

Among PLWH (a combination of PLWH on cART and PLWH who were cART-naïve), the mean age of participants increased from 43.3 ± 8.6 years for those with normoglycaemia, 44.9 ± 9.2 years for those with pre-DM, and 50.6 ± 10.5 years for those with DM (P < 0.0001). Across the three glycaemic states, the proportion of females with normoglycaemia was 77.5%, with pre-DM was 74.5% and with DM was 54.3% (P = 0.01). Other demographic characteristics are shown in Table 2.

| Characteristic |

Normoglycaemia (N = 364) |

Pre-diabetes (N = 102) |

Diabetes mellitus (N = 35) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (mean ± SD) | 43.3 ± 8.6 | 44.9 ± 9.2 | 50.6 ± 10.5 | < 0.0001 |

| Age categories | ||||

| 30–49 years | 283 (78.0) | 72 (70.6) | 19 (54.3) | 0.001 |

| 40–59 years | 60 (16.5) | 22 (21.6) | 8 (22.9) | |

| 60+ years | 20 (5.5) | 8 (7.8) | 8 (22.9) | |

| Female [n (%)] | 282 (77.5) | 76 (74.5) | 19 (54.3) | 0.01 |

| Location of residence | ||||

| Urban | 254 (70.0) | 78 (76.5) | 28 (80.0) | 0.36 |

| Semi-urban | 91 (25.0) | 22 (21.6) | 5 (14.3) | |

| Rural | 18 (5.0) | 2 (2.0) | 2 (5.7) | |

| Educational attainment | ||||

| No formal education | 98 (27.0) | 22 (21.6) | 8 (22.9) | 0.006 |

| Primary | 118 (32.5) | 39 (38.2) | 17 (48.6) | |

| Secondary | 120 (33.1) | 36 (35.3) | 3 (8.6) | |

| University/postgraduate | 27 (7.4) | 5 (4.9) | 7 (20.0) | |

| Duration of HIV diagnosis (mean ± SD) | 5.2 ± 4.8 | 4.1 ± 4.8 | 5.6 ± 5.3 | 0.11 |

| Nadir CD4 T count (cells/μL) [median (IQR)] | 234 (107–391) | 185 (86–347) | 134 (58–310) | 0.04 |

| Current CD4 T count (cells/μL) [median (IQR)] | 450 (237–723) | 348 (146–664) | 387 (173–810) | 0.03 |

| WHO staging at initiation | ||||

| 1 | 110 (33.2) | 28 (22.8) | 5 (7.2) | < 0.0001 |

| 2 | 84 (25.4) | 44 (35.8) | 7 (10.1) | |

| 3 | 114 (34.4) | 45 (36.6) | 51 (73.9) | |

| 4 | 23 (6.9) | 6 (4.9) | 6 (8.7) | |

| Proportion on cART | 0.001 | |||

| No cART | 159 (43.7) | 68 (66.7) | 16 (45.7) | 0.0002 |

| First line | 201 (55.2) | 33 (32.4) | 18 (51.4) | 0.0002 |

| Second line | 4 (1.1) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0.64 |

| cART regimens | ||||

| ZDV + 3TC/FTC + EFV | 51 (24.9) | 7 (20.6) | 7 (36.8) | 0.45 |

| ZDV + 3TC/FTC + NVP | 60 (29.3) | 8 (23.5) | 4 (21.1) | |

| D4T + 3TC + EFV | 15 (7.3) | 5 (14.7) | 1 (5.3) | |

| D4T + 3TC + NVP | 24 (11.7) | 2 (5.9) | 1 (5.3) | |

| TDF + 3TC/FTC + EFV | 47 (22.9) | 11 (32.4) | 4 (21.1) | |

| TDF + 3TC/FTC + NVP | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 2 NRTIs + PI/r | 4 (2.0) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (5.3) | |

| Others | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.3) | |

| Exposure to D4T [n (%)] | 44 (12.1) | 8 (7.8) | 5 (14.3) | 0.42 |

| Exposure to PI [n (%)] | 4 (1.1) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (2.9) | 0.64 |

| Duration on cART (years) (mean ± SD) | 4.4 ± 4.6 | 2.6 ± 4.4 | 4.7 ± 5.3 | 0.002 |

| Proportion with undetectable viral load | 144 (41.0) | 26 (26.5) | 12 (35.3) | 0.03 |

| Log viral load [median (IQR)] | 2.58 (1.30-5.00) | 4.38 (1.30-5.03) | 2.84 (1.30-5.05) | 0.09 |

| Log viral load (mean ± SD) | 3.13 ± 1.87 | 3.66 ± 1.71 | 3.26 ± 1.91 | 0.04 |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 25.8 ± 5.3 | 25.7 ± 6.1 | 24.9 ± 5.6 | 0.69 |

| BMI categories | 0.23 | |||

| Underweight | 17 (4.7) | 9 (8.9) | 3 (8.6) | 0.21 |

| Ideal weight | 170 (46.8) | 42 (41.6) | 20 (57.1) | 0.27 |

| Overweight | 105 (28.9) | 25 (24.8) | 5 (14.3) | 0.15 |

| Obese | 71 (19.6) | 25 (24.8) | 7 (20.0) | 0.52 |

| WHR (mean ± SD) | 0.87 ± 0.07 | 0.88 ± 0.08 | 0.92 ± 0.06 | 0.002 |

| Raised WHR [n (%)] | 216 (59.3) | 61 (59.8) | 27 (77.1) | 0.12 |

| Alcohol | ||||

| Current user | 36 (10.0) | 12 (11.9) | 2 (5.7) | 0.58 |

| Never used | 325 (90.0) | 89 (88.1) | 33 (94.3) | |

| Cigarette smoking | ||||

| Current user | 4 (1.1) | 2 (2.0) | 1 (2.9) | 0.37 |

| Previous user | 20 (5.5) | 10 (9.8) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Never used | 339 (93.4) | 90 (88.2) | 33 (94.3) | |

| SBP (mmHg) (mean ± SD) | 121 ± 23 | 122 ± 23 | 125 ± 26 | 0.53 |

| DBP (mmHg) (mean ± SD) | 77 ± 14 | 79 ± 14 | 78 ± 14 | 0.63 |

| Proportion with hypertension [n (%)] | 101 (27.7) | 34 (33.3) | 16 (45.7) | 0.06 |

| eGFR (mean ± SD) | 84.3 ± 12.2 | 82.6 ± 14.8 | 85.6 ± 8.1 | 0.38 |

| Total cholesterol (mean ± SD) | 4.8 ± 1.3 | 4.9 ± 1.3 | 4.8 ± 1.5 | 0.71 |

| LDL cholesterol (mean ± SD) | 2.93 ± 0.95 | 3.05 ± 1.00 | 2.91 ± 1.10 | 0.54 |

| HDL cholesterol (mean ± SD) | 1.29 ± 0.47 | 1.21 ± 0.41 | 1.15 ± 0.43 | 0.08 |

| Triglyceride (mean ± SD) | 1.27 ± 0.64 | 1.45 ± 0.70 | 2.30 ± 2.28 | < 0.0001 |

- cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; IQR, interquartile range; ZDV, zidovudine; 3TC, lamivudine; FTC, emtricitabine; EFV, efavirenz; NVP, nevirapine; D4T, stavudine; TDF, tenofovir; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; PI/r, ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor; BMI, body mass index; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

In terms of HIV features, median (interquartile range) nadir CD4 T-cell count declined from 234 (107–391) cells/µL among the normoglycaemic group to 185 (86–347) cells/µL among the pre-DM group, and to 134 (58–310) cells/µL among the diabetes group (P = 0.04), which largely corresponded to baseline WHO clinical stage distribution. There were proportionally more participants with pre-DM who were cART-naïve at enrolment (66.7%) than with normoglycaemia (43.7%) and DM (45.7%). Participants with normoglycaemia were most likely to have undetectable viral load (Table 2).

In relation to their cardiovascular risk profiles, the mean waist-to-hip ratio increased from 0.87 ± 0.07 in normoglycaemia, to 0.88 ± 0.08 in pre-DM and 0.92 ± 0.06 among those with DM (P = 0.0002). Similarly, the proportions with hypertension increased from 27.7% in normoglycaemia, to 33.3% in pre-DM and 45.7% in those with DM (P = 0.06). Finally, mean HDL cholesterol concentrations decreased from normoglycaemia to DM, while triglyceride followed a reverse distribution (Table 2).

Factors associated with prevalent DM, pre-DM and dysglycaemia among PLWH

The factors independently associated with pre-DM, DM and dysglycaemia at enrolment are presented as adjusted odds ratio (aOR) and 95% CI in Table 3. Classification of glycaemic status for these analyses was by combination of medical history and HBA1c cut-offs. Pre-DM was independently associated with being on cART [aOR = 0.35 (95% CI: 0.18–0.69)]. DM was independently associated with increasing age [aOR = 1.82 (1.20–2.77) for each 10-year rise], male sex [aOR = 2.64 (1.20–5.80)] and log(triglyceride/HDL cholesterol) [aOR = 8.54 (2.53–28.83)]. Dysglycaemia was broadly independently associated with increasing age, cART exposure and triglyceride/HDL cholesterol ratio as shown in Table 3.

| Risk factors | Pre-DM | DM | Dysglycaemia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Age (each 10-yeaer increase) | 1.23 (0.96–1.57) | – | 2.12 (1.50–2.99) | 1.82 (1.20–2.77) | 1.45 (1.17–1.79) | 1.51 (1.16–1.96) |

| Male gender | 1.18 (0.71–1.96) | – | 2.79 (1.39–5.62) | 2.64 (1.20–5.80) | 1.52 (0.98–2.36) | 1.24 (0.76–2.01) |

| Educational level | ||||||

| No education | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Primary level | 1.47 (0.82–2.65) | – | 1.62 (0.68–3.89) | – | 1.48 (0.89–2.46) | – |

| Secondary level | 1.26 (0.69–2.30) | – | 0.77 (0.28–2.11) | – | 1.20 (0.70–2.05) | – |

| Tertiary level | 0.82 (0.29–2.38) | – | 0.94 (0.19–4.63) | – | 0.85 (0.34–2.14) | – |

| Location of residence | ||||||

| Rural | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Urban | 2.61 (0.60–11.43) | – | 0.74 (0.17–3.31) | – | 1.73 (0.58–5.22) | – |

| WHO clinical stage | ||||||

| 1 and 2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 3 and 4 | 1.21 (0.78–1.88) | – | 2.01 (1.00–4.06) | 1.60 (0.74–3.46) | 1.41 (0.95–2.10) | – |

| Nadir CD4 T-cell count (each 50-cell rise) | 0.97 (0.93–1.02) | – | 0.94 (0.86–1.02) | – | 0.96 (0.92–1.01) | – |

| Current CD4 T-cell count (each 50-cell rise) | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) | 0.98 (0.94–1.02) | 1.02 (0.97–1.07) | – | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) | – |

| Being on cART | 0.39 (0.25–0.62) | 0.35 (0.18–0.69) | 1.14 (0.57–2.27) | – | 0.49 (0.33–0.74) | 0.38 (0.21–0.69) |

| Duration on cART | 0.91 (0.86–0.96) | ND* | 1.04 (0.97–1.1) | – | 0.94 (0.90–0.99) | ND |

| Exposure to stavudine | 1.13 (0.48–2.66) | – | 1.20 (0.42–3.45) | – | 1.16 (0.57–2.35) | – |

| Exposure to protease inhibitor | 1.52 (0.17–14.05) | – | 2.46 (0.27–22.17) | – | 1.93 (0.34–10.84) | – |

| Log(viral load) | 1.17 (1.03–1.32) | 0.90 (0.75–1.09) | 0.97 (0.81–1.17) | – | 1.13 (1.02–1.26) | 0.95 (0.81–1.13) |

| Hypertension | 1.30 (0.81–2.09) | – | 2.06 (1.03–4.14) | 1.57 (0.73–3.39) | 1.50 (0.99–1.00) | 1.46 (0.91–2.34) |

| Log(TG/HDL) | 2.53 (1.19–5.36) | 1.57 (0.66–3.75) | 3.69 (1.89–7.20) | 8.54 (2.53–28.83) | 3.69 (1.89–7.20) | 2.40 (1.09–5.25) |

| Raised to waist-to-hip ratio | 2.12 (0.11-39.98) | – | 2.30 (1.02–5.18) | 2.08 (0.83–5.18) | 15.14 (1.06-217.02) | 1.42 (0.06–34.43) |

| Cigarette smoking | 1.88 (0.91–3.91) | – | 0.70 (0.16–3.04) | – | 1.61 (0.81–3.21) | – |

| Alcohol | 1.22 (0.61–2.44) | – | 0.51 (0.12–2.18) | – | 1.04 (0.54–1.99) | – |

- OR, odds ratio (unadjusted); aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; ND, not included in adjusted models; TG, triglyiceride; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

- * Interactions between duration on cART and being on cART.

cART regimen of participants during follow-up

During the prospective 12-month follow-up, 150 cART-naïve HIV-positive participants were initiated on cART, comprising tenofovir + lamivudine (TDF/3TC) with efavirenz (EFV; 139/150, 92.7%), nevirapine (NVP; 2/150, 1.3%), ritonavir-boosted lopinavir (LPV/r) (1/150, 0.7%); zidovudine + lamivudine (ZDV/3TC) with NVP (3/150, 2.0%), EFV (1/150, 0.7%) or LPV/r (1/150, 0.7%); and abacavir (ABC) + 3TC with EFV (3/150, 2.0%). However, among 256 cART-experienced participants who were followed up, cART regimens comprised a dual nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) backbone of ZDV/3TC and EFV (64/256, 25.0%), NVP (76/256, 29.7%) or LPV/r (2/256, 0.8%); or TDF/3TC and EFV (88/256, 34.4%), NVP (8/256, 3.1%), LPV/r (14/256, 5.5%) or ABC (2/256, 0.8%), with one each on ABC/3TC/ritonavir (RTV)-boosted atazanavir and stavudine (D4T)/3TC/LPV/r, respectively. Thus the proportions of participants on new-generation NRTI (TDF) vs. old-generation NRTI (ZDV/D4T) were higher among cART-naïve participants who started cART during follow-up, with a TDF/ZDV ratio of 142/5 (28.4) vs. 112/142 (0.8) among cART-experienced participants (P < 0.0001).

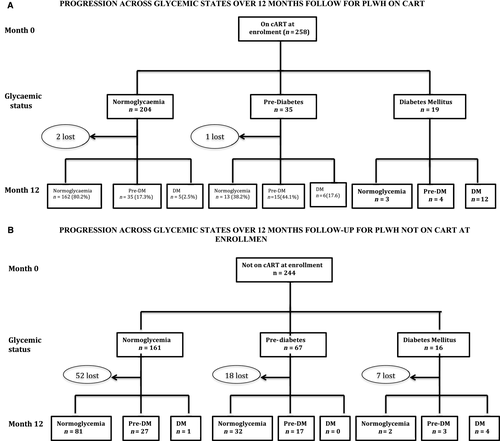

Progression across glycaemic states over 12 months

PLWH on cART at enrolment

Among PLWH on cART at enrolment, 202 out of 204 who were normoglycaemic completed 12 months of follow-up, of whom 162 (80.2%) remained normoglycaemic, 35 (17.3%) progressed to pre-DM and five (2.5%) developed new-onset DM (Fig. 1). Among those with pre-DM, 34 out of 35 completed 12 months of follow-up, of whom 13 (38.2%) regressed to normoglycaemia, 15 (44.1%) remained in pre-DM and six (17.6%) progressed to DM. All 19 who were DM completed follow-up, of whom three (15.8%), four (21.1%) and 12 (63.1%) had HBA1c values within normoglycaemic, pre-DM and DM status at month 12, respectively (Fig. 1a).

PLWH not on cART at enrolment

After collecting baseline data, cART-naïve PLWH were started on cART and followed up for 12 months. Among 161 who were normoglycaemic at baseline, 109 had follow-up glycaemic data, with 81 (74.3%) remaining euglycaemic, 27 (24.8%) progressing to pre-DM and one (0.9%) progressing to DM. There were 49 out of 67 with pre-DM who had follow-up glycaemic data, with 32 (65.3%) regressing to normoglycaemia, 17 (35.7%) remaining at pre-DM and none progressing to DM. (Fig. 1B).

Incidence rates of dysglycaemic states among PLWH

The incidence rate for new-onset DM was calculated for PLWH who were either normoglycaemic or pre-DM at enrolment. There were a total of 12 cases of incident DM over 359.25 person-years giving an incidence rate of 33.4/1000 PYFU (95% CI: 18.1–56.8/1000). The incidence rate of DM among PLWH on cART at enrolment was 47.5/1000 PFYU (25.0–82.6/1000) vs. 7.7/1000 PYFU (0.4–38.1/1000) (P = 0.04) among those who were initially cART-naïve at enrolment. Among PLWH who were normoglycaemic at enrolment with follow-up glycaemic assessments, 62 out of 365 progressed to pre-DM status with an incidence rate of 212.7/1000 PYFU (164.5–270.9/1000), partitioned into 175.9/1000 PYFU among those already on cART before follow-up vs. 291.9/1000 PYFU for those who were cART-naïve before follow-up (P = 0.05). These incidence rate data were based on HBA1c data collected during follow-up.

Predictors of incident dysglycaemic states

Table 4 shows the results of a multi-variable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with new-onset composite dysglycaemic state of pre-DM and/or DM. Raised total cholesterol at month 12 was independently associated with risk of progression to a dysglycaemic state with an aOR (95% CI) of 2.04 (1.09–3.81) (P = 0.03). The two independent factors associated with new-onset diabetes were having pre-DM at enrolment [aOR = 6.27 (1.89–20.81)] and being established on cART for 1 year on more at enrolment [aOR = 12.02 (1.48–97.70)].

| Risk factor | Progression to dysglycaemic states (pre-DM or DM) | Progression to new-onset DM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | P-value for aOR | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | P-value for aOR | |

| Age (each 10-year rise) | 1.33 (1.00–1.75) | 1.31 (0.95–1.82) | 0.10 | 1.57 (0.87–2.86) | – | – |

| Female sex | 1.10 (0.59–2.06) | – | – | 3.10 (0.39–24.36) | – | – |

| Urban residence | 1.67 (0.92–3.05) | – | – | 2.15 (0.46–9.98) | – | – |

| WHO stage 3/4 | 1.36 (0.82–2.27) | – | – | 1.78 (0.55–5.71) | – | – |

| Established on cART at enrolment vs. cART-naïve at enrolment | 1.12 (0.67–1.89) | – | – | 7.68 (0.99–60.06)† | 12.02 (1.48-97.70) | 0.02 |

| Use of protease inhibitor | 2.68 (1.02–7.07) | 1.56 (0.15–15.99) | 0.71 | Not done* | – | – |

| Use of ZDV vs. TDF as referent | 1.05 (0.61–1.81) | – | – | 1.14 (0.35–3.65) | – | – |

| Pre-DM at enrolment | Not done | – | – | 3.96 (1.24–12.62) | 6.27 (1.89-20.81) | 0.003 |

| Systolic BP (each 10 mmHg rise) | 1.11 (0.99–1.26) | – | – | 1.95 (0.58–6.56) | – | – |

| Total cholesterol ≥ 5.2 mmol/L | 2.07 (1.14–3.77) | 1.91 (1.04–3.50) | 0.04 | 1.95 (0.58–6.56) | – | – |

| Triglyceride | 1.22 (0.80–1.88) | – | – | 1.68 (0.87–3.22) | – | – |

| HDL cholesterol | 1.08 (0.61–1.91) | – | – | 0.73 (0.19–2.81) | – | – |

- OR, odds ratio (unadjusted); aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; ZDV, zidovudine; TDF, tenofovir; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

- * Model did not converge due to no event among those on protease inhibitors.

- † Bivariate P-value = 0.05.

Discussion

In this longitudinal study, we report on the prevalence and the incidence rates of dysglycaemic states in a prospective cohort of PLWH. The prevalence of DM of 7.4% among PLWH on cART and 6.6% among cART-naïve PLWH was not significantly different from the 6.6% found among HIV-negative controls. There was, however, a two-fold higher prevalence of pre-DM among the cART-naïve PLWH group than among the PLWH established on cART at enrolment based on glycated haemoglobin values. We identified male sex, increasing age and elevated triglyceride/HDL cholesterol ratio to be independently associated with baseline dysglycaemic status. We found a high incidence rate of new-onset DM of 33.4/1000 PYFU and of pre-DM of 212.7/1000 PYFU over 12 months of follow-up. Incident DM was independently predicted by baseline pre-DM status and being on established cART at enrolment, while new-onset dysglycaemic state (a composite of pre-DM and DM) was associated with raised total cholesterol at month 12.

Available data from 15 studies conducted in eight African countries found the prevalence of DM in retrospective or cross-sectional studies to range between 1% and 26%, and that of pre-DM to range between 19% and 47% [22-36. All these previous studies used self-reports of DM, FBG measurements or 2-h glucose tolerance test [27, 28, 30 and none used glycosylated haemoglobin. We utilized glycosylated haemoglobin, FBG measurements and self-reported history of diabetes to classify a participant’s glycaemic status. Using our FBG data, the prevalence rates of DM and pre-DM among PLWH were 13.5% and 48.0%, respectively, which concurs with previous prevalence studies from Africa [22-36. However, by using HBA1c data, we detected a lower burden of glucose disorders, namely 7.0% for DM and 20.3% for pre-DM. These discrepancies are in agreement with observations that glycosylated haemoglobin may under-diagnose glucose disorders and under-estimate glucose control in PLWH. The degree of discordance between HBA1c and FBG among PLWH is influenced by low CD4 count (< 500 cells/µL), high mean corpuscular volume and cART regimens such as use of protease inhibitor (PIs) or ZDV [37, 38. For instance, we observed among PLWH on cART that there was a profound variance in prevalence of pre-DM at 53.1% using FBG vs. 13.6% with HBA1c. It is likely that macrocytosis induced by ART on PLWH on cART could account for this wide difference in prevalence of pre-DM assessed using these two tests. Notably, this gap was narrower among PLWH who were cART-naïve, among whom prevalence of pre-DM was 42.6% by FBG and 27.5% by HBA1c, as well as among the HIV-negative group (40.6% vs. 26.5%; Table 1). These findings have implications on screening tests for diagnosing dysglycaemia in PLWH and require further studies.

We emphasized HBA1c during follow-up evaluations, however, because its values were less susceptible to dramatic between-visit fluctuations compared with FBG values. Thus for prospective assessment of incidence of new-onset dysglycaemic states we utilized HBA1c data. We found a comparatively high incidence of new-onset DM of 33.4/1000 PYFU (95% CI: 18.1–56.8/1000) over a 12-month follow-up period. Of the seven studies in SSA to report incidence of DM among PLWH, four from South Africa found incidence rates of 11, 5, 13 and 59/1000 PYFU [39-42, one from Democratic Republic of Congo found 10/1000 PYFU [43, and one each from Burkina Faso [44 and Benin [45 found 7/1000 and 4/1000 PYFU, respectively. The incidence rate of DM in our study exceeds that of several studies conducted outside Africa, including 5.7/1000 from the D:A:D cohort [46, 5.0/1000 PYFU from Thailand [47, 10.2/1000 from Australia [48, 14.1/1000 PYFU from France [49, and 17.0–25.0/1000 PYFU in the United States Women’s Interagency HIV study [50, 51. However, the Multicenter AIDS cohort study in the US [3 found a much higher incidence rate of 47/1000 PYFU. These inter-study differences in incidence rates reflect differences in sex and age distribution, ethnicity, ascertainment methodology for dysglycaemic states, duration of cohort follow-up and local cART regimens used for HIV treatment.

The unique aspect of the present study is that we followed up two cohorts of PLWH: those already established on cART and those who started cART upon enrolment into the study. There were notable differences in incidence rates of DM between the two groups. Namely, the incidence rate of DM among the cART-experienced group was significantly higher at 47.5/1000 PYFU vs. 7.7/1000 PYFU noted among those who recently initiated cART therapy. This reflects the known association between prolonged exposure to cART and risk of blood glucose abnormalities. Furthermore, the two groups differed in NRTIs used for treatment. For instance, while 55% of the cART-experienced group were on ZDV-based cART, only 3% of the group recently initiated on cART were on ZDV, the majority being on TDF. There is now overwhelming evidence implicating cumulative exposure to older-generation thymidine analogues such as ZDV or D4T compared with newer-generation agents (TDF and ABC) in the pathogenesis of lipodystrophy via mitochondrial DNA polymerase γ inhibition [52, 53. In addition, the cART-experienced group were more likely than the recently cART-initiated group to be on RTV-boosted protease inhibitor therapy as part of second-line therapy (7% vs. 1%) found to mediate insulin resistance [54. In our multivariate logistic regression models, being on a PI was non-significantly associated with an aOR of 1.56 (95% CI: 0.15–15.99) for progression to dysglycaemia from a normoglycaemic state. We did not include PIs in our models of new-onset diabetes because all newly diagnosed DM were on PI-based therapy. However, being on TDF relative to ZDV appeared to confer a minimal risk of progression to DM. It is possible that longer-term follow-up may unveil the detrimental associations between older generations of NRTIs and DM risk.

Compared with findings from an Australian study [48 where incidence rate of pre-DM was 24.3/1000 PYFU, we found a 10-fold higher rate of 212.7/1000 PYFU (95 CI: 164.5–270.9/1000) among those who were normoglycaemic at baseline. Here, we noted a near two-fold higher incidence rate among the group recently commissioned on cART relative to the cART-experienced group. This observation is noteworthy given that the reduction of mitochondrial DNA content and respiratory chain activity in adipocytes, which are pathophysiological precursory perturbations to dysglycaemic states, occurs within 6–12 months of commencing NRTI therapy [53. Pre-DM, an intermediate phase in abnormal glucose metabolism, may either progress to overt DM or regress back into normoglycaemia. In the present study, progression from pre-DM to overt DM or regression back to a normoglycaemic state followed different trajectories for the two groups. We found that nearly 18% of those who were pre-DM on established cART treatment at enrolment progressed to DM over a 12-month follow-up, while none in the cART-naïve group who were initiated on cART progressed to DM. In fact, 65% of cART-naïve participants regressed to normoglycaemia following the initiation of cART, compared with 38% of cART-experienced participants. These findings suggest that cART may have an initial salutary effect on abnormal glucose metabolism among those with pre-DM at cART initiation, potentially via the declines in viral load and concomitant reduction in the pro-inflammatory milieu thought to contribute to adipocyte insulin resistance and altered lipid handling. However, ongoing prolonged exposure of cART may subsequently provoke disruptions in the bioenergetics pathways which when combined with the chronic inflammatory state associated with HIV infection and ageing may then shift the balance towards the development of diabetes.

Implications

Clinical trials are needed to test the efficacy of pharmacological interventions such as early use of anti-diabetic agents, anti-inflammatory agents and therapeutic lifestyle modifications among PLWH with pre-DM to prevent overt DM in the SSA setting. These interventions have been shown to interrupt progression from pre-DM to DM in the general population in high-income countries [55-57. Certainly, the need for these studies is justified by the huge burden of HIV in SSA and the concomitant astronomic rise in burden of cardiovascular diseases on the continent [58-61. The design of such trials should be guided by implementation science principles with hybrid study designs to evaluate both effectiveness and implementation outcomes. Such as approach will facilitate the rapid integration of evidence-based interventions for CVD risk mitigation into routine clinical care in a region with severe constraints on national health budgets. There is certainly a need to focus on enhancing continued adherence to a higher pill burden of CVD medications along with the cART regimen, which fortunately is increasingly becoming simpler with once-daily tablet formulations available in Africa. Furthermore, laboratory screening for dysglycaemic states should become a routine to facilitate earlier diagnosis and initiation of treatment. In our study, a significant proportion of those we diagnosed with DM through this study were hitherto undiagnosed in routine care. As is often the case in our setting, delayed diagnosis of these insidious dysglycaemic states results in devastating microvascular and macrovascular complications with attendant significant reductions in health-related quality of life of PLWH in particular [62, 63. Undoubtedly, the implementation of these measures into strategic policies in Africa constitutes the next major hurdle to confront and surmount in the chronic stable phase of the HIV pandemic. Indeed the co-occurrence of type 2 DM among PLWH will significantly increase the economic burden at both patient and national levels [64. Innovative approaches and strategic partnerships between governments, non-governmental organizations and foreign partners are required to reverse these dire trends and improve care for PLWH with CVD comorbidities.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study are the longitudinal follow-up, which allowed us to calculate incidence rates of new-onset DM and pre-DM, the presence of both males and females subjects, and the use of both HBA1c and FBG to classify blood glucose abnormalities. However, our use of both FBG and HBA1c showed poor agreement in glycaemic status classification. This could reflect the effect of cART-induced macrocytosis and, in the African context, the presence haemoglobinopathies, which may affect the utility of HBA1c. This might favour the use of oral glucose tolerance testing to diagnose blood glucose abnormalities in subsequent studies. Other limitations include a higher loss to follow-up rate among cART-naïve participants than those already established on cART. The reasons for attrition included deaths, transfers to other HIV treatment sites or worsening of clinical status upon initiation of cART. This may have inevitably resulted in survivorship bias. Furthermore, data on institution of lifestyle modifications during follow-up were not captured to assess its impact on transitions across the dysglycaemic spectrum. Again, it would have been ideal also to follow-up HIV-negative controls to obtain comparative incidence data. However, only a handful of HIV-negative controls returned, despite persistent calls for their 12-month visit for glycaemic assessments. The aforementioned limitations should be addressed in subsequent studies. The age cut-off of 30 years and above limits the generalization of our findings. Overall, our study contributes to the literature in that it shows high incidence rates of both DM and pre-DM almost three decades into the post-cART era. We highlight the need for interventions aimed at improving the cardiovascular health of PLWH who are now living longer thanks to the life-prolonging effects of cART.

Conclusions

Incidence rates of pre-DM and overt DM among Ghanaian PLWH on cART rank among the highest in the literature. There is thus an urgent need for routine screening and a multi-disciplinary approach to CVD risk reduction among PLWH to reduce morbidity and mortality from the detrimental effects of dysglycaemia.