Influence of noninjecting and injecting drug use on mortality, retention in the cohort, and antiretroviral therapy, in participants in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study

Abstract

Objectives

We studied the influence of noninjecting and injecting drug use on mortality, dropout rate, and the course of antiretroviral therapy (ART), in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS).

Methods

Cohort participants, registered prior to April 2007 and with at least one drug use questionnaire completed until May 2013, were categorized according to their self-reported drug use behaviour. The probabilities of death and dropout were separately analysed using multivariable competing risks proportional hazards regression models with mutual correction for the other endpoint. Furthermore, we describe the influence of drug use on the course of ART.

Results

A total of 6529 participants (including 31% women) were followed during 31 215 person-years; 5.1% participants died; 10.5% were lost to follow-up. Among persons with homosexual or heterosexual HIV transmission, noninjecting drug use was associated with higher all-cause mortality [subhazard rate (SHR) 1.73; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.07–2.83], compared with no drug use. Also, mortality was increased among former injecting drug users (IDUs) who reported noninjecting drug use (SHR 2.34; 95% CI 1.49–3.69). Noninjecting drug use was associated with higher dropout rates. The mean proportion of time with suppressed viral replication was 82.2% in all participants, irrespective of ART status, and 91.2% in those on ART. Drug use lowered adherence, and increased rates of ART change and ART interruptions. Virological failure on ART was more frequent in participants who reported concomitant drug injections while on opiate substitution, and in current IDUs, but not among noninjecting drug users.

Conclusions

Noninjecting drug use and injecting drug use are modifiable risks for death, and they lower retention in a cohort and complicate ART.

Introduction

Drug use and alcohol use affect somatic and mental health, cause social conflicts, impair access to and outcomes of medical care, and – among HIV-positive persons – may complicate antiretroviral therapy (ART) 1-6. Individual virological ART failure, drug-related risky sexual behaviour and sharing of paraphernalia for drug injection have serious public health consequences, including the increased risk of transmission of HIV, hepatitis viruses and sexually transmitted infections. Care of HIV-positive persons with concomitant drug or alcohol use is complex because multiple somatic, psychological and social factors, linked to substance use and HIV infection, need to be addressed.

Whereas research on drug use among HIV-positive persons has often focused on injecting drug users (IDUs), the influence of noninjecting drug use on the course of HIV infection and ART is less evident 7. Direct biological effects of drug use have been postulated to influence the progression of HIV infection or the response to ART: cocaine and morphine were found to enhance HIV replication in vitro, and to have immunosuppressive effects in vitro and in animal studies; cannabinoids were postulated to decrease resistance to infectious diseases 8-13. CD4 cell recovery during ART was shown to be less pronounced among IDUs compared with non-IDUs 14. Also, clinical studies suggested accelerated HIV disease progression among IDUs independent of ART 15-18. However, indirect consequences of drug use may have a greater impact on outcome, including limited access to care, lower or late uptake of ART, decreased adherence to therapy, potential interactions between ART and opiate substitution or illicit drugs, and adverse effects of drugs. Poverty, malnutrition, depression and injection-related bacterial and hepatitis virus infections may add to morbidity in HIV-positive persons. Moreover, physicians may be hesitant to offer ART to patients with ongoing drug use, which may result in delayed start of ART and worse outcome 19.

We aimed to investigate how noninjecting and injecting drug use influenced all-cause mortality, causes of death, the retention rate in the cohort, and the course and outcome of ART among participants in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS).

Methods

Data collection

The SHCS (http://www.shcs.ch), initiated in 1988, is a prospective observational study of HIV-infected persons, aged ≥ 16 years, treated at out-patient clinics of five university hospitals and two large district hospitals 20. In addition, 35% of the participants are followed by private physicians and 10% by associated regional hospitals collaborating with the SHCS centres. Drug addiction treatment programmes are not carried out by the SHCS centres but by authorized specialized institutions or authorized private physicians.

Standardized data-collection forms containing demographic, epidemiological, clinical, laboratory and treatment information are completed every 6 months by physicians and study nurses. An interviewer-administered questionnaire on sexual behaviour was introduced in 2000; self-reported adherence to ART has been documented since 2003 21; alcohol consumption since 2005; and illicit or recreational injecting and noninjecting drug use since April 2007.

Study participants

We included in the study participants, registered prior to April 2007, who had at least one follow-up visit until May 2013 with completion of the drug use questionnaire. We limited the analysis to the main HIV transmission categories: men who have sex with men (MSM), heterosexuals and IDUs. The SHCS has been approved by local ethical committees and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Outcomes

Study outcomes were: all-cause mortality, cause of death, retention rate in the SHCS, and the course and outcome of ART, including ART status at cohort visits, time to starting ART if not on ART, ART changes, ART interruptions, proportion of HIV-1 RNA measurements below the level of detection, and mean proportion of follow-up time with suppressed viral replication, (a) irrespective of ART status and (b) in patients on ART.

Definitions

Among participants who never injected drugs, we distinguished – according to their self-reported drug use – ‘no drug use’ and ‘noninjecting drug use’. In some analyses, cannabis use was separated from all noninjecting drug use.

- (1)

Former IDUs (complete cessation of injecting drug use; not on opiate substitution),

- (a)

without or

- (b)

with concomitant noninjecting drug use.

- (a)

- (2)

Persons in methadone or buprenorphine substitution treatment programmes,

- (a)

without or

- (b)

with concomitant injecting drug use.

- (a)

- (3)

Persons in an injection heroin substitution programme.

- (4)

Current IDUs.

An interviewer-administered questionnaire was used at every 6-monthly cohort visit to assess injecting drug use (yes, no or no answer; heroin, cocaine or other; specification of other), noninjecting drug use (yes, no or no answer; heroin, cocaine, cannabis or other; specification of other) and the frequency of drug use (daily, weekly, monthly, less frequently or unknown). Other injected drugs reported are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

| Total | HIV transmission risk | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSM | Heterosexual | IDU | ||

| Cohort participants [total n (%)] | 6529 (100) | 2411 (36.9) | 2432 (37.2) | 1686 (25.8) |

| Women [n (%)] | 2023 (31.0) | 0 | 1427 (58.7) | 596 (35.4) |

| Age (years) [median (IQR)] | 44 (39, 50) | 45 (40, 52) | 43 (37, 50) | 44 (40, 48) |

| CD4 count (cells/μL) [median (IQR)] | 478 (337, 671) | 491 (363, 685) | 479 (330, 666) | 456 (300, 651) |

| Follow-up | ||||

| Total number of follow-up visits | 62,317 | 24,039 | 23,468 | 14,810 |

| Number of visits/participant [median (IQR)] | 11 (10, 12) | 11 (9, 12) | 11 (9, 12) | 10 (7, 11) |

| Total years of follow-up | 32,215 | 12,291 | 12,122 | 7802 |

| Follow-up years/participant [median (IQR)] | 5.4 (5.0, 5.7) | 5.5 (5.1, 5.7) | 5.4 (5.0, 5.7) | 5.3 (4.1, 5.6) |

| Antiretroviral therapy [n (%)] | ||||

| ART-naïve | 640 (9.8) | 279 (11.6) | 233 (9.6) | 128 (7.6) |

| On ART | 5319 (81.5) | 1950 (80.9) | 1967 (80.8) | 1402 (83.1) |

| HIV RNA < 50 copies/mL if on ART > 6 months | 4286 (87.2) | 1592 (88.0) | 1582 (86.9) | 1112 (86.5) |

| Off ART | 570 (8.7) | 182 (7.6) | 232 (9.5) | 156 (9.3) |

| Coinfections [n (%)] | ||||

| Active HCV coinfection | 1785 (27.3) | 190 (7.9) | 186 (7.7) | 1409 (83.6) |

| Active HBV coinfection | 251 (3.8) | 112 (4.7) | 80 (3.3) | 59 (3.5) |

| Drug use pattern [n (%)] | ||||

| Smoking | ||||

| Current | 3099 (47.5) | 963 (39.9) | 810 (33.3) | 1326 (78.7) |

| Former | 1436 (22.0) | 604 (25.1) | 552 (22.7) | 280 (16.6) |

| Alcohol use | ||||

| Light | 2777 (42.5) | 1374 (57.0) | 876 (36.0) | 527 (31.3) |

| Moderate | 335 (5.1) | 82 (3.4) | 132 (5.4) | 121 (7.2) |

| Heavy | 148 (2.3) | 29 (1.2) | 34 (1.4) | 85 (5.0) |

| Injecting drugs | ||||

| Heroin | 114 (1.8) | 0 | 0 | 114 (6.8) |

| Cocaine | 160 (2.5) | 0 | 0 | 160 (9.5) |

| Other | 10 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 10 (0.6) |

| Noninjecting drugs | ||||

| Amphetamines | 77 (1.2) | 59 (2.5) | 4 (0.2) | 14 (0.8) |

| Cannabis | 948 (14.5) | 255 (10.6) | 117 (4.8) | 576 (34.2) |

| Cocaine | 228 (3.5) | 93 (3.9) | 15 (0.6) | 120 (7.2) |

| γ-Hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) | 17 (0.3) | 12 (0.5) | 0 | 5 (0.3) |

| Heroin or other opiates | 100 (1.6) | 0 | 2 (0.1) | 98 (1.7) |

| Sedatives, hypnotics and anxiolytics | 40 (0.6) | 4 (0.2) | 0 | 36 (2.1) |

| Other | 7 (0.1) | 4 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) | 5 (0.3) |

- ART, antiretroviral therapy; IQR, interquartile range; MSM, men who have sex with men; IDU, injecting drug use; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

| Baseline variable | Never injecting drug use | IDU transmission group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No drug use | Noninjecting drug use | Former IDU | In opiate substitution treatment programme | Current IDU | ||||

| No drug use | With noninjecting drug use | Methadone, no injecting drug use | Methadone, with concomitant injecting drug use | Heroin substitution | ||||

| Cohort participants [total n (%)] | 4382 (67.1) | 461 (7.1) | 659 (10.1) | 319 (4.9) | 487 (7.5) | 130 (2.0) | 52 (0.8) | 39 (0.6) |

| Women [n (%)] | 1375 (31.4) | 52 (11.3) | 260 (39.5) | 97 (30.4) | 170 (34.9) | 39 (30.9) | 17 (32.7) | 13 (33.0) |

| Antiretroviral therapy [n (%)] | ||||||||

| ART-naïve | 432 (9.9) | 80 (17.3) | 43 (6.5) | 24 (7.5) | 34 (7.0) | 16 (12.3) | 5 (9.6) | 6 (15.4) |

| On ART | 3673 (81.5) | 344 (74.6) | 568 (86.2) | 264 (82.8) | 405 (83.1) | 96 (73.8) | 42 (80.8) | 27 (69.3) |

| HIV RNA < 50 copies/mLa | 2904 (87.5) | 270 (87.1) | 471 (88.2) | 202 (85.2) | 307 (84.6) | 72 (85.7) | 38 (92.7) | 22 (84.6) |

| Good adherenceb | 3089 (93.1) | 285 (91.9) | 485 (90.8) | 208 (87.8) | 330 (90.9) | 64 (76.2) | 33 (80.5) | 18 (69.2) |

| Off ART | 377 (8.6) | 37 (8.0) | 48 (7.3) | 31 (9.7) | 48 (9.9) | 18 (13.9) | 5 (9.6) | 6 (15.4) |

| Drug use pattern [n (%)] | ||||||||

| Smoking, current | 1469 (33.5) | 304 (65.9) | 401 (60.9) | 272 (85.3) | 447 (91.8) | 123 (94.6) | 50 (96.2) | 33 (84.6) |

| Alcohol use, heavy | 58 (1.3) | 5 (1.1) | 18 (2.7) | 13 (4.1) | 30 (6.2) | 14 (10.8) | 6 (11.5) | 4 (10.3) |

| Injecting drugs | ||||||||

| Heroin, total | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 56 (43.1) | 36 (69.2) | 22 (56.4) |

| Less than monthly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 (15.4) | 1 (1.9) | 6 (15.4) |

| Monthly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 (8.5) | 0 | 2 (5.1) |

| Weekly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 (19.2) | 1 (1.9) | 7 (18.0) |

| Daily | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34 (65.4) | 7 (18.0) |

| Cocaine, total | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 112 (86.2) | 20 (38.5) | 28 (71.8) |

| Less than monthly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 (23.1) | 1 (1.9) | 8 (20.5) |

| Monthly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 (22.3) | 2 (3.9) | 9 (23.1) |

| Weekly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38 (29.2) | 6 (11.5) | 8 (20.5) |

| Daily | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 (11.5) | 11 (21.2) | 3 (7.7) |

| Other, total | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 (5.4) | 0 | 3 (7.7) |

| Noninjecting drugs | ||||||||

| Amphetamines | 0 | 63 (13.7) | 0 | 10 (3.1) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (1.5) | 0 | 1 (2.6) |

| Cannabis, total | 0 | 372 (80.7) | 0 | 284 (89.0) | 189 (38.8) | 61 (46.9) | 19 (36.5) | 23 (59.0) |

| Less than monthly | 0 | 59 (12.8) | 0 | 30 (9.4) | 14 (2.9) | 2 (2.3) | 2 (3.9) | 2 (5.1) |

| Monthly | 0 | 60 (13.0) | 0 | 14 (4.4) | 17 (3.5) | 12 (9.2) | 5 (5.8) | 2 (5.1) |

| Weekly | 0 | 127 (27.6) | 0 | 73 (22.9) | 54 (11.1) | 21 (16.2) | 4 (7.7) | 7 (18.0) |

| Daily | 0 | 126 (27.3) | 0 | 167 (52.4) | 104 (21.4) | 25 (19.2) | 10 (19.2) | 12 (30.8) |

| Cocaine | 0 | 108 (23.4) | 0 | 47 (14.7) | 45 (9.2) | 13 (10) | 5 (9.6) | 10 (25.6) |

| γ-Hydroxybutyric acid | 0 | 12 (2.6) | 0 | 3 (0.94) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.6) |

| Heroin or other opiates | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 15 (4.7) | 49 (10.1) | 7 (6.1) | 19 (36.5) | 7 (18.0) |

| Sedatives and hypnotics | 0 | 4 (0.9) | 0 | 3 (0.9) | 23 (4.7) | 2 (1.5) | 3 (5.8) | 5 (12.8) |

- ART, antiretroviral therapy; IDU, injecting drug use.

- a If on ART for more than 6 months.

- b Never or only once missed a dose in last 4 weeks.

Average daily alcohol consumption was estimated using a predefined list of different beverages with their alcohol content in grams (g), and translated into World Health Organization (WHO) risk categories: light (< 20 g for women and < 40 g for men), moderate (20–40 and 40–60 g, respectively) and severe (> 40 and > 60 g, respectively) health risk.

ART status was categorized as treatment-naïve, on ART or off ART. Treatment interruptions of ≥ 14 days were documented. Suppressed viral replication was defined as HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL.

Good adherence to therapy was defined as ‘never or only once missed a dose in the last 4 weeks’.

Active hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection was defined as being HCV RNA-positive; active hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection as being HBV surface (HBs) or HBe antigen-positive or HBV DNA-positive.

Causes of death were categorized according to the Causes of Death in HIV (CoDe) classification 22, 23.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were compared using χ2 tests, and continuous variables were assessed with nonparametric methods (Wilcoxon rank sum for two groups or Kruskal − Wallis tests if more than two groups). Baseline was defined as the first cohort visit after 1 April 2007, when the questionnaire on drug use was introduced. We analysed the time from baseline to the two endpoints death or dropout separately using Kaplan−Meier methods and competing risks proportional hazards regression models with mutual correction for the other endpoint 24. Multivariable models were adjusted for sex, alcohol use (none, light, moderate or heavy), CD4 cell count (per 100 cells/μL higher) and age (per 10 years older). We evaluated survival and dropout probabilities with time-updated variables but did not pursue this approach further because of reverse causality problems with drug using behaviour. Thus, all time-to-event models shown in this study are including baseline variables only.

We used time-updated information on drug use and ART to calculate the proportion of follow-up time with suppressed viral replication for all participants and for participants on ART for at least 6 months. Results are presented as means with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the proportion of time spent in the different drug use categories with suppressed viral replication. Similarly, we used time-updated drug use to calculate the percentage of participants on ART with self-reported good adherence.

We further calculated the prevalence of depression per follow-up visit with time-updated drug use, as well as the probability of treatment changes, treatment interruptions and follow-up gaps of > 9 months per year.

We used stata (version 13.0; StataCorp, College Station, TX) for analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 7018 participants were seen during the study period between April 2007 and May 2013; 266 were excluded because of HIV transmission risks other than MSM, heterosexual contacts or IDU; and 223 because of a missing drug use questionnaire. Thus, 6529 participants, including 2023 (31%) women, were included in the study, contributing to 62 317 visits (median of 11 visits/participant) and 31 215 person-years of follow-up (median of 5.4 years/participant) (Table 1). HIV transmission risks were MSM (36.9%), heterosexual contacts (37.2%) and IDU (25.8%).

Active coinfections with HCV were present in 1785 participants (overall 27.3%; IDU 83.6%; MSM 7.9%; heterosexuals 7.7%) and active coinfections with HBV in 251 participants (3.8%).

Drug use patterns

Ongoing smoking and prior smoking were reported by 47.5% and 22.0% of participants, and moderate and heavy alcohol use by 5.1% and 2.3%, respectively (Table 1). A total of 948 (14.5%) participants disclosed cannabis use, 228 (3.5%) noninjecting cocaine use, 100 (1.6%) noninjecting opiate use and 77 (1.2%) amphetamine use. Current injecting drug use comprised use of heroin (6.8%), cocaine (9.5%) and other drugs (0.6%).

Among participants who never injected drugs, 9.5% reported noninjecting drug use (Table 2). The IDU transmission group included 58.0% former IDUs, separated into persons without and with noninjecting drug use, 36.6% persons in a methadone substitution programme (without or with concomitant injecting drug use), 3.1% in a heroin substitution treatment programme, and 2.3% current IDUs.

Mortality

During the observation period, 334 (5.1%) participants died, the proportion ranging from 3.6% among persons with no drug use to 20% in participants in a methadone programme with concomitant injecting drug use (Table 3).

| Total | Never injecting drug use | IDU transmission group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No drug use | Noninjecting drug use | Former IDU | Opiate substitution | Current IDU | |||||

| No drug use | With noninjecting drug use | Methadone, no IDU | Methadone, concomitant IDU | Heroin substitution | |||||

| Total participants [n (%)] | 6529 (100) | 4382 (67.1) | 461 (7.1) | 659 (10.1) | 319 (4.9) | 487 (7.5) | 130 (2.0) | 52 (0.8) | 39 (0.6) |

| Deaths [n (%)] | 334 (5.1) | 156 (3.6) | 22 (4.8) | 28 (4.2) | 25 (7.8) | 71 (14.6) | 26 (20.0) | 2 (3.9) | 4 (10.3) |

| Dropouts [n (%)] | 688 (10.5) | 405 (9.2) | 60 (13.0) | 72 (10.9) | 35 (11.0) | 74 (15.2) | 21 (16.2) | 10 (19.2) | 11 (28.2) |

| Treatment status at last visit [n (%)] | |||||||||

| ART-naïve, total | 129 (2.0) | 83 (1.9) | 13 (2.8) | 8 (1.2) | 4 (1.3) | 10 (2.1) | 6 (4.6) | 2 (3.9) | 3 (7.7) |

| ART-naïve, CD4 < 350 cells/μL | 20 (0.3) | 10 (0.2) | 3 (0.7) | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 2 (5.1) |

| On ART | 6183 (94.7) | 4173 (95.2) | 430 (93.3) | 625 (94.8) | 306 (95.9) | 459 (94.3) | 112 (86.2) | 48 (92.3) | 30 (76.9) |

| Off ART (not ART-naïve) | 217 (3.3) | 126 (2.9) | 18 (3.9) | 26 (4.0) | 9 (2.8) | 18 (3.7) | 12 (9.2) | 2 (3.9) | 6 (15.4) |

| HIV RNA | |||||||||

| Percentage of follow-up time with HIV RNA < 50 copies/mL irrespective of ART [mean (95% CI)]1) | 82.2 (81.6, 82.8) | 82.9 (82.1, 83.6) | 80.2 (78.3, 82.1) | 84.4 (82.7, 86.0) | 81.2 (78.9, 83.6) | 82.3 (80.4, 84.2) | 76.2 (72.1, 80.2) | 83.1 (77.6, 88.5) | 74.6 (68.6, 80.6) |

| Percentage of follow-up time with HIV RNA < 50 copies/mL on ART [mean (95% CI)] | 91.2 (90.8, 91.6) | 91.5 (91.0, 92.0) | 91.5 (90.3, 92.6) | 91.7 (90–5, 92.8) | 90.1 (88.4, 91.8) | 90.6 (89.2, 92.0) | 88.4 (85.2, 91.6) | 92.6 (89.0, 96.2) | 87.6 (82.7, 92.5) |

| Adherence parameters | |||||||||

| Percentage with good adherence [% (95% CI)]* | 94.4 (94.2, 94.6) | 95.4 (95.3, 95.6) | 93.0 (92.3, 93.8) | 94.5 (94.0, 95.0) | 90.6 (89.6, 91.6) | 91.4 (90.6, 92.1) | 85.8 (83.5, 88.2) | 90.1 (87.0, 93.2) | 80.9 (76.0, 85.7) |

| Probability of treatment interruptions > 1 week/year [% (95% CI)] | 4.2 (3.8, 4.5) | 3.5 (3.1, 3.9) | 3.3 (2.2, 4.5) | 4.7 (3.6, 5.8) | 6.3 (4.3, 8.4) | 7.1 (5.2, 9.0) | 8.2 (3.9, 12.6) | 5.7 (0.4, 11.0) | 8.5 (2.0, 15.1) |

| Probability of follow-up gap > 9 months/year [% (95% CI)] | 16.2 (15.7, 18.6) | 15.4 (14.7, 16.0) | 14.8 (12.9, 16.7) | 17.7 (15.6, 19.8) | 17.7 (14.9, 20.5) | 19.4 (17.1, 21.7) | 23.1 (18.8, 27.4) | 22.1 (16.5, 27.7) | 27.1 (15.8, 38.3) |

| ART change, probability/year [% (95% CI)] | |||||||||

| Total, any reason | 40.1 (39.7, 42.1) | 38.8 (37.5, 40.1) | 40.3 (36.3, 44.3) | 40.1 (36.8, 43.4) | 44.6 (39.6, 49.7) | 54.8 (47.7, 61.9) | 50.2 (42.4, 58.0) | 38.3 (26.6, 50.0) | 47.1 (31.2, 62.9) |

| Treatment failure | 2.6 (2.2, 3.0) | 2.8 (2.3, 3.3) | 2.6 (1.6, 3.6) | 1.6 (1.1, 2.2) | 3.1 (1.4, 4.9) | 2.4 (1.1, 3.7) | 2.4 (0.6, 4.1) | 1.3 (-0.5, 3.2) | 2.7 (-1.3, 6.7) |

| Physicians' decision | 15.1 (14.4, 15.8) | 14.7 (13.9, 15.5) | 13.6 (10.8, 16.5) | 14.7 (13.0, 16.5) | 16.2 (13.3, 19.1) | 19.6 (16.1, 23.0) | 17.3 (11.8, 22.7) | 9.3 (4.8, 13.8) | 13.4 (5.9, 20.8) |

| Patient's wish | 10.4 (9.7, 11.2) | 9.0 (8.2, 9.8) | 12.3 (9.2, 15.5) | 10.3 (8.7, 12.0) | 13.9 (9.9, 17.8) | 16.4 (12.7, 20.2) | 17.4 (9.9, 24.8) | 9.9 (2.5, 17.2) | 23.8 (7.1, 40.5) |

| Any adverse event | 12.7 (12.1, 13.4) | 12.4 (11.6, 13.1) | 11.8 (10.0, 13.6) | 13.4 (11.1, 15.8) | 11.4 (9.2, 13.7) | 16.4 (12.7, 20.2) | 13.2 (9.5, 16.9) | 17.8 (10.1, 25.6) | 7.2 (1.8, 12.7) |

| Depression, probability/follow-up visit [% (95% CI)] | 12.5 (12.0, 13.0) | 9.5 (8.9, 10.1) | 16.0 (13.8, 18.1) | 16.4 (14.5, 18.2) | 18.0 (15.3, 20.8) | 23.1 (20.7, 25.6) | 22.1 (17.5, 26.6) | 16.2 (10.4, 22.0) | 25.6 (17.9, 33.3) |

- ART, antiretroviral therapy; CI, confidence interval; IDU, injecting drug use.

- *Defined as missing not more than one dose per month, drug use pattern time-updated.

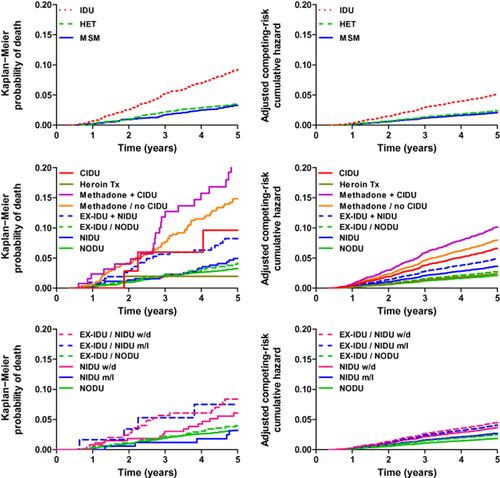

Multivariable analyses with dropout as a competing risk (Table 4) showed associations of all-cause death with higher age, lower CD4 cell count, smoking and noninjecting drug use. The risk of death was not increased among former IDUs who completely stopped any drug use, and in persons in the heroin substitution treatment programme. In contrast, mortality was higher in the case of noninjecting drug use among former IDUs, methadone substitution, and continued injecting drug use (Fig. 1). Heavy alcohol use was a risk for death in the univariable but not in the multivariable models, possibly because of the low prevalence of heavy alcohol use among persons who never injected drugs.

| Dropouta | Deathb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable analyses | Multivariable analyses | Univariable analyses | Multivariable analyses | |||||

| SHR (95% CI) | p | SHR (95% CI) | p | SHR (95% CI) | p | SHR (95% CI) | p | |

| Model 1: HIV transmission groupsc | ||||||||

| MSM | 1 | < 0.001 | 1 | < 0.001 | 1 | < 0.001 | 1 | < 0.001 |

| Heterosexual | 1.38 (1.14, 1.65) | 1.36 (1.09, 1.69) | 1.05 (0.783, 1.41) | 1.16 (0.841, 1.59) | ||||

| IDU transmission group | 1.71 (1.42, 2.08) | 1.53 (1.23, 1.89) | 2.73 (2.10, 3.54) | 2.49 (1.85, 3.35) | ||||

| Model 2: drug use patterns | ||||||||

| No drug use | 1 | < 0.001 | 1 | 0.002 | 1 | < 0.001 | 1 | < 0.001 |

| Noninjecting drug use | 1.46 (1.12, 1.91) | 1.32 (1.00, 1.75) | 1.38 (0.883, 2.16) | 1.73 (1.07, 2.83) | ||||

| Former IDU, no drug use | 1.20 (0.938, 1.54) | 1.14 (0.883, 1.46) | 1.20 (0.804, 1.79) | 1.31 (0.861, 1.99) | ||||

| Former IDU, noninjecting drug use | 1.23 (0.867, 1.74) | 1.11 (0.779, 1.59) | 2.31 (1.51, 3.54) | 2.34 (1.49, 3.69) | ||||

| Methadone, no IDU | 1.80 (1.40, 2.31) | 1.60 (1.22, 2.11) | 4.58 (3.46, 6.06) | 3.91 (2.80, 5.46) | ||||

| Methadone, concomitant IDU | 1.92 (1.24, 2.99) | 1.62 (1.02, 2.58) | 6.57 (4.35, 9.92) | 5.03 (3.22, 7.85) | ||||

| Injecting heroin substitution | 2.22 (1.19, 4.14) | 1.75 (0.916, 3.33) | 1.12 (0.278, 4.49) | 1.14 (0.274, 4.73) | ||||

| Current IDU | 3.59 (1.99, 6.49) | 2.88 (1.56, 5.30) | 3.17 (1.18, 8.51) | 3.20 (1.16, 8.86) | ||||

| Smokingc | 1.35 (1.16, 1.56) | <0.001 | 1.10 (0.926, 1.31 | 0.28 | 2.40 (1.91, 3.02) | <0.001 | 2.11 (1.59, 2.80) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol use, nonec | 1 | 0.021 | 1 | 0.32 | 1 | < 0.001 | 1 | 0.001 |

| Light | 0.907 (0.774, 1.06) | 0.974 (0.827, 1.15) | 0.667 (0.524, 0.848) | 0.676 (0.521, 0.876) | ||||

| Moderate | 1.18 (0.850, 1.62) | 1.14 (0.820, 1.57) | 1.62 (1.09, 2.40) | 1.19 (0.807, 1.76) | ||||

| Heavy | 1.67 (1.10, 2.53) | 1.45 (0.940, 2.24) | 2.71 (1.71, 4.28) | 1.44 (0.922, 2.25) | ||||

| Female sexc | 1.19 (1.02, 1.39) | 0.032 | 1.08 (0.913, 1.28) | 0.36 | 0.791 (0.620, 1.01) | 0.059 | 0.933 (0.722, 1.21) | 0.60 |

| Age per 10 years olderc | 0.756 (0.687, 0.826) | <0.001 | 0.769 (0.695, 0.852) | <0.001 | 1.74 (1.59, 1.91) | <0.001 | 2.24 (1.99, 2.53) | <0.001 |

| CD4 count per 100 cells/μL higherc | 0.982 (0.954, 1.01) | 0.21 | 0.987 (0.959, 1.02) | 0.37 | 0.859 (0.813, 0.908) | <0.001 | 0.897 (0.853, 0.944) | <0.001 |

| Model 3: quantified noninjecting drug used | ||||||||

| No drug use | 1 | 0.003 | 1 | < 0.001 | 1 | 0.003 | 1 | < 0.001 |

| Noninjecting drug use monthly or less | 1.05 (0.641, 1.70) | 0.967 (0.590, 1.58) | 0.935 (0.415, 2.11) | 1.45 (0.629, 3.35) | ||||

| Noninjecting drug use weekly or daily | 1.74 (1.27, 2.37) | 1.58 (1.14, 2.18) | 1.67 (1.00, 2,80) | 1.97 (1.10, 3.54) | ||||

| Former IDU, no drug use | 1.20 (0.938, 1.54) | 1.12 (0.873, 1.45) | 1.20 (0.803, 1.78) | 1.33 (0.871, 2.03) | ||||

| Former IDU, noninjecting drug use monthly or less | 2.16 (1.17, 4.00) | 1.94 (1.04, 3.61) | 1.93 (0.705, 5.26) | 2.20 (0.764, 6.33) | ||||

| Former IDU, noninjecting drug use weekly or daily | 1.03 (0.679, 1.55) | 0.921 (0.604, 1.40) | 2.40 (1.51, 3.79) | 2.45 (1.50, 4.00) | ||||

| Model 4: quantified cannabis usede | ||||||||

| No drug use | 1 | 0.008 | 1 | < 0.001 | 1 | 0.017 | 1 | < 0.001 |

| Cannabis, monthly or less | 1.04 (0.533, 2.02) | 0.960 (0.491, 1.88) | 1.48 (0.610, 3.61) | 2.03 (0.806, 5.14) | ||||

| Cannabis, weekly or daily | 1.83 (1.28, 2.61) | 1.70 (1.18, 2.45) | 2.21 (1.30, 3.75) | 2.28 (1.23, 4.22) | ||||

| Former IDU, no drug use | 1.20 (0.938, 1.54) | 1.12 (0.872, 1.45) | 1.20 (0.803, 1.78) | 1.33 (0.871, 2.04) | ||||

| Former IDU, cannabis monthly or less | 2.20 (1.01, 4.76) | 1.95 (0.885, 4.28) | 2.36 (0.730, 7.61) | 2.37 (0.673, 8.33) | ||||

| Former IDU, cannabis weekly or daily | 1.01 (0.634, 1.59) | 0.914 (0.570, 1.46) | 1.80 (1.02, 3.19) | 1.78 (0.99, 3.20) | ||||

- CI, confidence interval; IDU, injecting drug use; MSM, men who have sex with men; SHR, subhazard rate (SHRs are interpreted similarly to hazard ratios in Cox regression).

- a With death as a competing risk.

- b With dropout as a competing risk.

- c Because multivariable estimates for sex, age, CD4 cell count, smoking and alcohol use are very similar across models, we only show them for model 2.

- d Adjusted for sex, age, CD4 cell count, smoking and alcohol use.

- e Any noninjecting drug use.

Probability of death. Left column: Kaplan−Meier probability of all-cause death. Right column: competing risks regression of endpoint death with dropout as a competing risk. Analyses were adjusted for age, sex, CD4 cell count, smoking and alcohol. Upper panels: comparison of the HIV transmission groups: injecting drug users (IDU), persons with heterosexual HIV transmission (HET) and men who have sex with men (MSM). Middle panels: comparison of participants with different drug use patterns and different status of drug addiction treatment. NODU, no drug use (and never IDU); NIDU, noninjecting drug use (and never IDU); EX-IDU/NODU, former IDU and no noninjecting drug use; EX-IDU+NIDU, former IDU and ongoing noninjecting drug use; Methadone/no CIDU, methadone (or buprenorphine) substitution treatment programme and complete cessation of injecting drug use; Methadone+CIDU, methadone (or buprenorphine) substitution treatment programme and concomitant injecting drug use; Heroin Tx, heroin substitution treatment programme; CIDU, current IDU. Lower panels: comparison of participant groups with different frequency of noninjecting drug use (NIDU) versus no drug use (NODU). Persons in the NIDU group have no history of injecting drug use. EX-IDU are former IDUs who have completely stopped injecting drug use. m/l, monthly or less frequent consumption; w/d, weekly or daily consumption of noninjecting drugs.

In models analysing the association of the frequency of noninjecting drug use and death (Table 4), overall weekly or daily noninjecting drug use [subhazard rate (SHR) 1.97; 95% CI 1.10, 3.54] and weekly or daily cannabis use (SHR 2.28; 95% CI 1.23, 4.22), respectively, increased mortality.

Causes of death

Frequent causes of death were non-AIDS-related malignancies (24.6%), cardiovascular diseases (10.2%), non-HIV-related infections (9.3%), AIDS-defining complications (8.1%), liver diseases (7.8%) and suicide (6.3%) (Table 5). A substantial number of causes of death remained undetermined (18.0%) because patients died outside of an institution.

| Never injecting drug use | IDU transmission group | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No drug use | Noninjecting drug use | Former IDU | Opiate substitution treatment programmes | Current injecting drug use | |||||

| No drug use | Noninjecting drug use | Methadone without injecting drug use | Methadone with concomitant injecting drug use | Heroin substitution | |||||

| Cohort participants | 4382 (67.1) | 461 (7.1) | 659 (10.1) | 319 (4.9) | 487 (7.5) | 130 (2.0) | 52 (0.8) | 39 (0.6) | 6529 (100) |

| Total deaths | 156 (3.6) | 22 (4.8) | 28 (4.3) | 25 (7.8) | 71 (14.6) | 26 (20.0) | 2 (3.9) | 4 (10.3) | 334 (5.1) |

| HIV/AIDS, total | 15 (9.6) | 3 (13.6) | 1 (3.6) | 0 | 5 (7.0) | 2 (7.7) | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 27 (8.1) |

| Substance use | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 4 (16.0) | 8 (11.3) | 4 (15.4) | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 18 (5.4) |

| Suicide or psychiatric disease | 12 (7.7) | 2 (9.1) | 1 (3.6) | 4 (16.0) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (3.9) | 0 | 0 | 21 (6.3) |

| Accident or other violent death | 2 (1.3) | 1 (4.6) | 0 | 3 (12.0) | 3 (4.2) | 1 (3.9) | 0 | 0 | 10 (3.0) |

| Malignancy, non-AIDS, total | 48 (30.8) | 6 (27.3) | 11 (39.2) | 4 (16.0) | 11 (15.5) | 2 (7.7) | 0 | 0 | 82 (24.6) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) | 4 (2.6) | 1 (4.6) | 2 (7.1) | 1 (4.0) | 2 (2.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 (3.0) |

| Liver failure, total (excl. HCC) | 4 (2.6) | 2 (9.1) | 8 (28.6) | 2 (8.0) | 7 (9.9) | 2 (7.7) | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 26 (7.8) |

| Liver failure, caused by HCV/HBV | 0 | 0 | 7 (25.0) | 2 (8.0) | 7 (9.9) | 2 (7.7) | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 19 (5.7) |

| Liver failure, other | 4 (2.6) | 2 (9.1) | 1 (3.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 (2.1) |

| Infection, non-AIDS | 12 (7.7) | 0 | 2 (7.1) | 2 (8.0) | 7 (9.9) | 6 (23.1) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (25.0) | 31 (9.3) |

| Cardiovascular disease, total | 25 (16.0) | 0 | 1 (3.6) | 1 (4.0) | 5 (7.0) | 2 (7.7) | 0 | 0 | 34 (10.2) |

| Myocardial infarction/heart disease | 22 (14.1) | 0 | 1 (3.6) | 1 (4.0) | 3 (4.2) | 2 (7.7) | 0 | 0 | 29 (8.7) |

| Stroke | 3 (1.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (1.5) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.6) |

| Central nervous system disease (excl. stroke or malignancy) | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (3.6) | 0 | 2 (2.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (1.2) |

| Renal failure | 2 (1.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.9) | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.9) |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 3 (1.9) | 1 (4.6) | 1 (3.6) | 0 | 3 (4.2) | 2 (7.7) | 0 | 0 | 10 (3.0) |

| Lung disease (excl. malignancies and infections) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (4.6) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (1.2) |

| Other | 1 (0.6) | 1 (4.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.6) |

| Unknown | 28 (18.0) | 5 (22.7) | 2 (7.1) | 5 (20.0) | 16 (22.5) | 3 (11.5) | 1 (50.0) | 0 | 60 (18.0) |

- Values are n (%).

Retention rate in the cohort

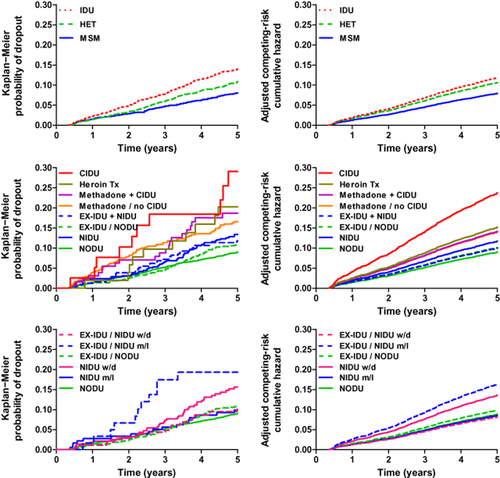

The proportion of persons who were lost to follow-up was 10.5%, ranging from 9% among persons without any drug use to 28% among current IDUs (Table 3).

Older age was associated with a lower dropout rate. The probability of dropout with death as a competing risk was increased among persons in a methadone substitution programme and current IDUs (Table 4 and Fig. 2). Also, noninjecting drug use overall and cannabis use were associated with dropout (Table 4).

Probability of drop-out from the cohort. Left column: Kaplan−Meier probability of dropout from the cohort. Right column: competing risks regression of endpoint dropout with death as a competing risk. Analyses were adjusted for age, sex, CD4 cell count, smoking and alcohol. Upper panels: comparison of the HIV transmission groups: injecting drug users (IDU), persons with heterosexual HIV transmission (HET) and men who have sex with men (MSM). Middle panels: comparison of participants with different drug use patterns and different status of drug addiction treatment. NODU, no drug use (and never IDU); NIDU, noninjecting drug use (and never IDU); EX-IDU/NODU, former IDU and no noninjecting drug use; EX-IDU+NIDU, former IDU and ongoing noninjecting drug use; Methadone/no CIDU, methadone (or buprenorphine) substitution treatment programme and complete cessation of injecting drug use; Methadone+CIDU, methadone (or buprenorphine) substitution treatment programme and concomitant injecting drug use; Heroin Tx, heroin substitution treatment programme; CIDU, current IDU. Lower panels: comparison of participant groups with different frequency of noninjecting drug use (NIDU) versus no drug use (NODU). Persons in the NIDU group have no history of injecting drug use. EX-IDU are former IDUs who have completely stopped injecting drug use. m/l, monthly or less frequent consumption; w/d, weekly or daily consumption of noninjecting drugs.

Antiretroviral therapy

At baseline, a total of 9.8% of all cohort participants were ART-naïve, 81.5% were on ART and 8.7% were off ART. More participants with noninjecting drug use (17%) or with ongoing injecting drug use (15%) were ART-naïve (Tables 1 and 2), but the probability of starting ART and the probability of restarting if off ART at baseline, respectively, were similar among groups with different drug use patterns (data not shown). In contrast, time to ART interruption and time to changing ART were shorter among the IDU transmission group (data not shown).

At the last visit, the proportion of ART-naïve participants was low, and 99.7% of participants with CD4 cell counts < 350 cells/μL were on ART (Table 3). The self-reported rate of adherence was similarly good among all groups except in current IDUs. The probabilities of treatment interruptions, of follow-up gaps and of ART change per year were higher among most IDU groups. Noninjecting drug use appeared not to influence these variables.

The probability of an ART change was higher among participants in a methadone substitution programme (Table 3). Virological failure as a reason for ART change was rare, and adverse events as reasons for ART change did not significantly differ between participant groups.

Time with suppressed viral replication

The mean proportion of follow-up time with suppressed viral replication was 82.2% in all cohort participants, irrespective of ART status, and 91.2% among participants on ART (Table 3). Except among current IDUs with worse virological outcome, proportions were not different in participants with different drug use patterns.

Depression

The probability of depression (reported at 6-monthly visits) was almost twice as high among noninjecting drug users (16%) compared with persons without any drug use (9.5%); the rates were higher among all IDU groups, ranging from 16 to 26%, and were particularly high among patients with methadone substitution or current IDU (Table 3).

Discussion

We observed 334 (5.1%) deaths among 6529 SHCS participants prospectively followed for 31 215 person-years. Noninjecting drug use overall, and cannabis use in particular, were associated with all-cause mortality among persons who never injected drugs. Moreover, smoking and heavy alcohol use and – among the IDU HIV transmission group – ongoing injecting drug use increased the risk for death. Mortality was mainly driven by non-HIV-associated causes. ART outcomes were excellent in the cohort overall – except among current IDUs – with a mean complete viral suppression during 91% of the follow-up time. However, maintenance of ART was more difficult among the IDU transmission group, as mirrored by a higher probability of ART interruptions, longer follow-up gaps, an increased probability of ART changes, and a higher rate of loss to follow-up. A lower probability of retention in the cohort was also observed among persons who reported weekly or daily cannabis consumption.

The association between noninjecting drug use and HIV disease progression in the era of ART was reviewed by Kipp et al. in 2011 7, who summarized the findings of nine observational cohort studies in the USA 25-33, of which eight studies examined women, and seven of these were carried out in the Women's Interagency HIV Study 27-31 or the Women and Infant Transmission Study 32, 33. The association with time to AIDS-related mortality after adjustment for cofactors was significant in only two studies 28, 31, whereas associations with death were uncertain. The authors explained the worse clinical outcome by lower or deferred ART uptake, or decreased adherence to ART. In other studies, no associations were found between recreational drug use and CD4 or CD8 cell count 34, or opportunistic complications such as Kaposi's sarcoma 35; but an association between amphetamine use and an increased risk of HIV-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma was reported 36.

A more rapid HIV disease progression among IDUs has mainly been explained by social and structural factors, accidental overdose, or injecting-related infections, whereas evidence for chronic toxicity of drugs was weak in clinical studies 1. Drug use as a cofactor of immunological or virological deterioration was considered before the availability of combination ART 37-39. When effective ART was introduced, HIV-associated morbidity and mortality were substantially reduced also among IDUs with access to care. Nevertheless, several studies have reported a more rapid disease progression among IDUs 25, 40-43, whereas others have not found differences compared with non-IDUs. Of note, many investigators categorized IDUs based on the HIV transmission risk group only, and did not consider different drug use behaviour, former versus current IDU, or status of drug addiction treatment. We showed that abstinent former IDUs and patients in opiate substitution programmes (who had completely stopped injecting illicit drugs) had similar uptake and success of ART to persons who had never injected drugs, whereas patients in opiate substitution programmes who continued injecting drug use and current IDUs were less likely to be on ART, more frequently interrupted ART, and had more ART failures 44.

In the present study, we could not determine whether the increased risk of death associated with noninjecting drug use was attributable to biological effects of drug use, behavioral or structural effects, or a combination of factors. Analysis of individual causes of death showed a similar pattern among participants without and with noninjecting drug use, but many patients died outside an institution, so the number of unknown causes of death was relatively high. ART uptake and virological response to ART were similar among participants with different drug use patterns, except in current IDUs. However, adherence to ART was lower, and the probabilities of ART interruptions, ART changes and follow-up gaps were higher, among persons with continuing injecting drug use. Depression may partially explain reduced adherence or increased rates of ART interruptions: the probability of reported depression was – compared with participants without any drug use – almost doubled among persons with noninjecting drug use, and among all groups in the IDU transmission category. Moreover, the rate of current or former smoking – contributing to increased risk of death also among HIV-positive persons 45 – was remarkably high among all participant groups, but particularly high among the IDU transmission group. Of note, adjustment for surrogates of behaviour, such as adherence to therapy, or adjustment for comorbidities, such as depression, was not done in our analyses to avoid overadjustment by using intermediate variables, or a descending proxy for an intermediate variable, which lie on the causal pathway from drug use behaviour to outcome 46, 47. Among IDU transmission groups, causes of death included a substantially higher proportion of liver-associated deaths as a consequence of hepatitis virus coinfections. A substantial number of drug-related deaths occurred among former IDUs with noninjecting drug use, and among patients in the opiate substitution programmes. Whether such deaths were attributable to drug overdose or to interactions with ART remains unknown.

Our cohort study has notable strengths because of the long-term prospective data collection, its large size, the comprehensive drug use questionnaire, and unrestricted access to ART. Potential limitations to our analyses include the following. (i) There was a higher loss to follow-up in IDUs, which may have led to an underestimation of IDU-associated mortality. We have, however, repeatedly cross-linked with the national death registry to establish the vital status of such patients 23, 48, 49. (ii) The 6-monthly cohort questionnaires assess drug use based on patients' self-reporting, which may be underreported because of socially desirable responding 50. Self-reporting, however, appears to have a good validity and high concordance with urine drug screens 51-53; and drug use was recorded in our study by SHCS investigators and not by the provider of the drug addiction treatment programmes. (iii) Although the SHCS was repeatedly found to be representative for HIV-positive persons in Switzerland and includes 75% of HIV-positive persons on ART 20, we assume that current IDUs were less likely to attend study centres, and the results obtained for this patient group may not be representative. Of note, mandatory health insurance allows unrestricted access to care in Switzerland.

In conclusion, in addition to injecting drug use, noninjecting drug use and smoking were also significant risks for death. Maintenance of ART and retention in the cohort were more difficult among noninjecting and injecting drug users. Our results indicate that comprehensive HIV care needs to incorporate interdisciplinary strategies to integrate prevention and treatment of these modifiable risk factors.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients attending our institutions for participating in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study, the physicians and study nurses for patient care, the data centre for logistical support, and the drug addiction treatment institutions for their excellent collaboration. This study has been financed within the framework of the Swiss HIV Cohort Study, supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 134277). The data are gathered by the five Swiss University Hospitals, two Cantonal Hospitals, 15 affiliated hospitals, and 36 private practitioners in Basel, Bern, Geneva, Lausanne and Zurich (listed at http://www.shcs.ch/31-health-care-providers).

Conflicts of interest: RW has received travel grants from Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharp & Dome, Pfizer, LaRoche, TRB Chemedica and Tibotec. MH has received travel grants from Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, ViiV and GlaxoSmithKline. MB has participated in advisory boards for Boehringer-Ingelheim, Gilead and Merck Sharp & Dome. MB's institution received unrestricted educational and/or research grants from Abbvie, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Gilead and ViiV Helathcare. CS has received travel grants from Gilead Sciences and Merck Sharp & Dome, and participated in an advisory board for Gilead Sciences. EC has received travel grants, grants or honoraria from Gilead, Janssen Cilag-AG and Merck Sharp & Dohme. AC has received travel grants from Gilead Sciences and Bristol-Myers Squibb and is the investigator in an investigator-initiated clinical trial funded by Janssen-Cilag. AB has no conflicts of interest. EB has participated in advisory boards for Abbott, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Gilead, Merck Sharp & Dome, Janssen and ViiV Healthcare. EB's institution has received unrestricted education grants from Abbott, Gilead and ViiV Healthcare. FSA has no conflicts of interest. BL has received travel grants, grants or honoraria from Abbott, Aventis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche and Tibotec.

Authors' contributions: RW and BL had full access to all the data of the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses. RW, MH and BL designed the study. RW wrote the first draft, and RW, MH and BL wrote the final version of the manuscript. BL analysed the data. All investigators contributed to data collection and interpretation of the data, reviewed drafts of the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript.

Appendix: the Swiss HIV Cohort Study

The members of the Swiss HIV Cohort Study group are: V. Aubert, J. Barth, M. Battegay, E. Bernasconi, J. Böni, H. C. Bucher, C. Burton-Jeangros, A. Calmy, M. Cavassini, M. Egger, L. Elzi, J. Fehr, J. Fellay, H. Furrer (Chairman of the Clinical and Laboratory Committee), C. A. Fux, M. Gorgievski, H. Günthard (President of the SHCS), D. Haerry (deputy of the ‘Positive Council’), H. Hasse, H. H. Hirsch, I. Hösli, C. Kahlert, L. Kaiser, O. Keiser, T. Klimkait, H. Kovari, R. Kouyos, B. Ledergerber, G. Martinetti, B. Martinez de Tejada, K. Metzner, N. Müller, D. Nadal, G. Pantaleo, A. Rauch (Chairman of the Scientific Board), S. Regenass, M. Rickenbach (Head of Data Center), C. Rudin (Chairman of the Mother & Child Substudy), P. Schmid, D. Schultze, F. Schöni-Affolter, J. Schüpbach, R. Speck, C. Staehelin, P. Tarr, A. Telenti, A. Trkola, P. Vernazza, R. Weber and S. Yerly.