The pathological and molecular genetic landscape of the hereditary renal cancer predisposition syndromes

Khaleel I Al-Obaidy

Department of Pathology, Robert J. Tomsich Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA

These authors contributed equally to this paper.

Search for more papers by this authorZainab I Alruwaii

Department of Pathology, Dammam Regional Laboratory and Blood Bank, Dammam, Saudi Arabia

These authors contributed equally to this paper.

Search for more papers by this authorSean R Williamson

Department of Pathology, Robert J. Tomsich Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA

Search for more papers by this authorCorresponding Author

Liang Cheng

Department of Pathology, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA

Department of Urology, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA

Address for correspondence: L Cheng MD, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, 350 West 11th Street, Room 4010, Indianapolis, Indiana 46202, USA. e-mail: [email protected]Search for more papers by this authorKhaleel I Al-Obaidy

Department of Pathology, Robert J. Tomsich Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA

These authors contributed equally to this paper.

Search for more papers by this authorZainab I Alruwaii

Department of Pathology, Dammam Regional Laboratory and Blood Bank, Dammam, Saudi Arabia

These authors contributed equally to this paper.

Search for more papers by this authorSean R Williamson

Department of Pathology, Robert J. Tomsich Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA

Search for more papers by this authorCorresponding Author

Liang Cheng

Department of Pathology, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA

Department of Urology, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA

Address for correspondence: L Cheng MD, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, 350 West 11th Street, Room 4010, Indianapolis, Indiana 46202, USA. e-mail: [email protected]Search for more papers by this authorAbstract

It is estimated that 5–8% of renal tumours are hereditary in nature, with many inherited as autosomal-dominant. These tumours carry a unique spectrum of pathological and molecular alterations, the knowledge of which has expanded in recent years. Due to this knowledge, many advances in the treatment of these tumours have been achieved. In this review, we summarize the current understanding of the genetic renal neoplasia syndromes, clinical and pathological presentations, molecular pathogenesis, advances in therapeutic implications and targeted therapy.

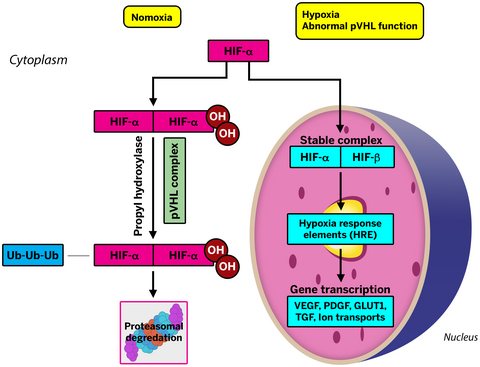

Graphical Abstract

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Open Research

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

References

- 1Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022; 72; 7–33.

- 2MacLennan GT, Cheng L. Five decades of urologic pathology: the accelerating expansion of knowledge in renal cell neoplasia. Hum. Pathol. 2020; 95; 24–45.

- 3Gudbjartsson T, Jonasdottir TJ, Thoroddsen A et al. A population-based familial aggregation analysis indicates genetic contribution in a majority of renal cell carcinomas. Int. J. Cancer 2002; 100; 476–479.

- 4Cheng L, Zhang S, MacLennan GT, Lopez-Beltran A, Montironi R. Molecular and cytogenetic insights into the pathogenesis, classification, differential diagnosis, and prognosis of renal epithelial neoplasms. Hum. Pathol. 2009; 40; 10–29.

- 5Von-Hippel E. Uber eine sehr seltene Erkrankung der Netzhaut [about a very rare disease of the retina]. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 1904; 59; 23.

- 6Lindau A. Zur frage der angiomatosis retinae und ihrer hirnkomplikationen [on the question of angiomatosis retinæ and its brain complications]. Acta Ophthalmol. 1926; 4; 193–226.

10.1111/j.1755-3768.1926.tb07786.x Google Scholar

- 7Richards FM, Maher ER, Latif F et al. Detailed genetic mapping of the von Hippel–Lindau disease tumour suppressor gene. J. Med. Genet. 1993; 30; 104–107.

- 8Latif F, Tory K, Gnarra J et al. Identification of the von Hippel–Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene. Science 1993; 260; 1317–1320.

- 9Richards FM, Phipps ME, Latif F et al. Mapping the Von Hippel–Lindau disease tumour suppressor gene: identification of germline deletions by pulsed field gel electrophoresis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1993; 2; 879–882.

- 10Iliopoulos O, Ohh M, Kaelin WG Jr. pVHL19 is a biologically active product of the von Hippel–Lindau gene arising from internal translation initiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998; 95; 11661–11666.

- 11Nordstrom-O'Brien M, van der Luijt RB, van Rooijen E et al. Genetic analysis of von Hippel–Lindau disease. Hum. Mutat. 2010; 31; 521–537.

- 12Shanbhogue KP, Hoch M, Fatterpaker G, Chandarana H. von Hippel–Lindau disease: review of genetics and imaging. Radiol. Clin. N. Am. 2016; 54; 409–422.

- 13Tang N, Mack F, Haase VH, Simon MC, Johnson RS. pVHL function is essential for endothelial extracellular matrix deposition. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006; 26; 2519–2530.

- 14Wang GL, Jiang BH, Rue EA, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995; 92; 5510–5514.

- 15Czyzyk-Krzeska MF. Molecular aspects of oxygen sensing in physiological adaptation to hypoxia. Respir. Physiol. 1997; 110; 99–111.

- 16Bunn HF, Poyton RO. Oxygen sensing and molecular adaptation to hypoxia. Physiol. Rev. 1996; 76; 839–885.

- 17Hsu T. Complex cellular functions of the von Hippel–Lindau tumor suppressor gene: Insights from model organisms. Oncogene 2012; 31; 2247–2257.

- 18Shenoy N, Pagliaro L. Sequential pathogenesis of metastatic VHL mutant clear cell renal cell carcinoma: Putting it together with a translational perspective. Ann. Oncol. 2016; 27; 1685–1695.

- 19Shen C, Beroukhim R, Schumacher SE et al. Genetic and functional studies implicate HIF1alpha as a 14q kidney cancer suppressor gene. Cancer Discov. 2011; 1; 222–235.

- 20Shen C, Kaelin WG Jr. The VHL/HIF axis in clear cell renal carcinoma. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2013; 23; 18–25.

- 21Kondo K, Kim WY, Lechpammer M, Kaelin WG Jr. Inhibition of HIF2alpha is sufficient to suppress pVHL-defective tumor growth. PLoS Biol. 2003; 1; E83.

- 22Varshney N, Kebede AA, Owusu-Dapaah H et al. A review of Von Hippel–Lindau syndrome. J. Kidney Cancer VHL 2017; 4; 20–29.

- 23Walther MM, Lubensky IA, Venzon D, Zbar B, Linehan WM. Prevalence of microscopic lesions in grossly normal renal parenchyma from patients with von Hippel–Lindau disease, sporadic renal cell carcinoma and no renal disease: clinical implications. J. Urol. 1995; 154; 2010–2014. discussion 2014–2015.

- 24de Peralta-Venturina M, Moch H, Amin M et al. Sarcomatoid differentiation in renal cell carcinoma: a study of 101 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2001; 25; 275–284.

- 25Williamson SR, Zhang S, Eble JN et al. Clear cell papillary renal cell carcinoma-like tumors in patients with von Hippel–Lindau disease are unrelated to sporadic clear cell papillary renal cell carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2013; 37; 1131–1139.

- 26Song Y, Fu Y, Xie Q et al. Anti-angiogenic agents in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A promising strategy for cancer treatment. Front. Immunol. 2020; 11; 1956.

- 27Tung I, Sahu A. Immune checkpoint inhibitor in first-line treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a review of current evidence and future directions. Front. Oncol. 2021; 11; 707214.

- 28Martinez-Saez O, Gajate Borau P, Alonso-Gordoa T, Molina-Cerrillo J, Grande E. Targeting HIF-2 alpha in clear cell renal cell carcinoma: a promising therapeutic strategy. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2017; 111; 117–123.

- 29Maher ER. Von Hippel–Lindau disease. Eur. J. Cancer 1994; 30A; 1987–1990.

- 30Richard S, Graff J, Lindau J, Resche F. Von Hippel–Lindau disease. Lancet 2004; 363; 1231–1234.

- 31Schmidt L, Junker K, Weirich G et al. Two north American families with hereditary papillary renal carcinoma and identical novel mutations in the MET proto-oncogene. Cancer Res. 1998; 58; 1719–1722.

- 32Lubensky IA, Schmidt L, Zhuang Z et al. Hereditary and sporadic papillary renal carcinomas with c-met mutations share a distinct morphological phenotype. Am. J. Pathol. 1999; 155; 517–526.

- 33Schmidt L, Duh FM, Chen F et al. Germline and somatic mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of the MET proto-oncogene in papillary renal carcinomas. Nat. Genet. 1997; 16; 68–73.

- 34Salvi A, Marchina E, Benetti A et al. Germline and somatic c-met mutations in multifocal/bilateral and sporadic papillary renal carcinomas of selected patients. Int. J. Oncol. 2008; 33; 271–276.

- 35Cecchi F, Rabe DC, Bottaro DP. The hepatocyte growth factor receptor: structure, function and pharmacological targeting in cancer. Curr. Signal Transduct. Ther. 2011; 6; 146–151.

- 36Kim ES, Salgia R. MET pathway as a therapeutic target. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2009; 4; 444–447.

- 37Zhang Y, Xia M, Jin K et al. Function of the c-met receptor tyrosine kinase in carcinogenesis and associated therapeutic opportunities. Mol. Cancer 2018; 17; 45.

- 38Fischer J, Palmedo G, von Knobloch R et al. Duplication and overexpression of the mutant allele of the MET proto-oncogene in multiple hereditary papillary renal cell tumours. Oncogene 1998; 17; 733–739.

- 39Launonen V, Vierimaa O, Kiuru M et al. Inherited susceptibility to uterine leiomyomas and renal cell cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001; 98; 3387–3392.

- 40Tomlinson IP, Alam NA, Rowan AJ et al. Germline mutations in FH predispose to dominantly inherited uterine fibroids, skin leiomyomata and papillary renal cell cancer. Nat. Genet. 2002; 30; 406–410.

- 41Barrisford GW, Singer EA, Rosner IL, Linehan WM, Bratslavsky G. Familial renal cancer: molecular genetics and surgical management. Int. J. Surg. Oncol. 2011; 2011; 658767.

- 42Isaacs JS, Jung YJ, Mole DR et al. HIF overexpression correlates with biallelic loss of fumarate hydratase in renal cancer: Novel role of fumarate in regulation of HIF stability. Cancer Cell 2005; 8; 143–153.

- 43Sudarshan S, Sourbier C, Kong HS et al. Fumarate hydratase deficiency in renal cancer induces glycolytic addiction and hypoxia-inducible transcription factor 1alpha stabilization by glucose-dependent generation of reactive oxygen species. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009; 29; 4080–4090.

- 44Tong WH, Sourbier C, Kovtunovych G et al. The glycolytic shift in fumarate-hydratase-deficient kidney cancer lowers AMPK levels, increases anabolic propensities and lowers cellular iron levels. Cancer Cell 2011; 20; 315–327.

- 45Bruick RK, McKnight SL. A conserved family of prolyl-4-hydroxylases that modify HIF. Science 2001; 294; 1337–1340.

- 46Sun G, Zhang X, Liang J et al. Integrated molecular characterization of fumarate hydratase-deficient renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021; 27; 1734–1743.

- 47Laukka T, Mariani CJ, Ihantola T et al. Fumarate and succinate regulate expression of hypoxia-inducible genes via TET enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 2016; 291; 4256–4265.

- 48Arts RJ, Novakovic B, Ter Horst R et al. Glutaminolysis and fumarate accumulation integrate immunometabolic and epigenetic programs in trained immunity. Cell Metab. 2016; 24; 807–819.

- 49Xiao M, Yang H, Xu W et al. Inhibition of alpha-KG-dependent histone and DNA demethylases by fumarate and succinate that are accumulated in mutations of FH and SDH tumor suppressors. Genes Dev. 2012; 26; 1326–1338.

- 50Alaghehbandan R, Stehlik J, Trpkov K et al. Programmed death-1 (PD-1) receptor/PD-1 ligand (PD-L1) expression in fumarate hydratase-deficient renal cell carcinoma. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2017; 29; 17–22.

- 51Zhang C, Li L, Zhang Y, Zeng C. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer: Recent insights into mechanisms and systemic treatment. Front. Oncol. 2021; 11; 686556.

- 52Leshets M, Silas YBH, Lehming N, Pines O. Fumarase: from the TCA cycle to DNA damage response and tumor suppression. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2018; 5; 68.

- 53Network CGAR, Linehan WM, Spellman PT et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of papillary renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016; 374; 135–145.

- 54Grubb RL III, Franks ME, Toro J et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer: a syndrome associated with an aggressive form of inherited renal cancer. J. Urol. 2007; 177; 2074–2079. discussion 2079–2080.

- 55Smit DL, Mensenkamp AR, Badeloe S et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer in families referred for fumarate hydratase germline mutation analysis. Clin. Genet. 2011; 79; 49–59.

- 56Schmidt LS, Linehan WM. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma. Int. J. Nephrol. Renov. Dis. 2014; 7; 253–260.

- 57Skala SL, Dhanasekaran SM, Mehra R. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma syndrome (HLRCC): A contemporary review and practical discussion of the differential diagnosis for HLRCC-associated renal cell carcinoma. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2018; 142; 1202–1215.

- 58Curatolo P, Bombardieri R, Jozwiak S. Tuberous sclerosis. Lancet 2008; 372; 657–668.

- 59De Waele L, Lagae L, Mekahli D. Tuberous sclerosis complex: the past and the future. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2015; 30; 1771–1780.

- 60Sancak O, Nellist M, Goedbloed M et al. Mutational analysis of the TSC1 and TSC2 genes in a diagnostic setting: genotype–phenotype correlations and comparison of diagnostic DNA techniques in tuberous sclerosis complex. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2005; 13; 731–741.

- 61Plank TL, Yeung RS, Henske EP. Hamartin, the product of the tuberous sclerosis 1 (TSC1) gene, interacts with tuberin and appears to be localized to cytoplasmic vesicles. Cancer Res. 1998; 58; 4766–4770.

- 62Napolioni V, Curatolo P. Genetics and molecular biology of tuberous sclerosis complex. Curr. Genomics 2008; 9; 475–487.

- 63Han JM, Sahin M. TSC1/TSC2 signaling in the CNS. FEBS Lett. 2011; 585; 973–980.

- 64Rakowski SK, Winterkorn EB, Paul E et al. Renal manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex: incidence, prognosis, and predictive factors. Kidney Int. 2006; 70; 1777–1782.

- 65Brook-Carter PT, Peral B, Ward CJ et al. Deletion of the TSC2 and PKD1 genes associated with severe infantile polycystic kidney disease–a contiguous gene syndrome. Nat. Genet. 1994; 8; 328–332.

- 66Crino PB, Nathanson KL, Henske EP. The tuberous sclerosis complex. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006; 355; 1345–1356.

- 67Krueger DA, Northrup H, International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex surveillance and management: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr. Neurol. 2013; 49; 255–265.

- 68Song X, Liu Z, Cappell K et al. Natural history of patients with tuberous sclerosis complex related renal angiomyolipoma. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2017; 33; 1277–1282.

- 69Gu L, Peng C, Zhang F, Fang C, Guo G. Sequential everolimus for angiomyolipoma associated with tuberous sclerosis complex: a prospective cohort study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021; 16; 277.

- 70Bissler JJ, Kingswood JC, Radzikowska E et al. Everolimus for angiomyolipoma associated with tuberous sclerosis complex or sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis (EXIST-2): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2013; 381; 817–824.

- 71Schreiner A, Daneshmand S, Bayne A et al. Distinctive morphology of renal cell carcinomas in tuberous sclerosis. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2010; 18; 409–418.

- 72Guo J, Tretiakova MS, Troxell ML et al. Tuberous sclerosis-associated renal cell carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 57 separate carcinomas in 18 patients. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2014; 38; 1457–1467.

- 73Trpkov K, Hes O, Bonert M et al. Eosinophilic, solid, and cystic renal cell carcinoma: clinicopathologic study of 16 unique, sporadic neoplasms occurring in women. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2016; 40; 60–71.

- 74Yang P, Cornejo KM, Sadow PM et al. Renal cell carcinoma in tuberous sclerosis complex. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2014; 38; 895–909.

- 75Kapur P, Gao M, Zhong H et al. Germline and sporadic mTOR pathway mutations in low-grade oncocytic tumor of the kidney. Mod. Pathol. 2022; 35; 333–3431.

- 76Lerma LA, Schade GR, Tretiakova MS. Co-existence of ESC-RCC, EVT, and LOT as synchronous and metachronous tumors in six patients with multifocal neoplasia but without clinical features of tuberous sclerosis complex. Hum. Pathol. 2021; 116; 1–11.

- 77Mansoor M, Siadat F, Trpkov K. Low-grade oncocytic tumor (LOT) – a new renal entity ready for a prime time: an updated review. Histol. Histopathol. 2022; 18435. https://doi.org/10.14670/HH-18-435.

- 78Gupta S, Jimenez RE, Herrera-Hernandez L et al. Renal neoplasia in tuberous sclerosis: a study of 41 patients. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021; 96; 1470–1489.

- 79Farcas M, Gatalica Z, Trpkov K et al. Eosinophilic vacuolated tumor (EVT) of kidney demonstrates sporadic TSC/MTOR mutations: next-generation sequencing multi-institutional study of 19 cases. Mod. Pathol. 2022; 35; 344–351.

- 80Nickerson ML, Warren MB, Toro JR et al. Mutations in a novel gene lead to kidney tumors, lung wall defects, and benign tumors of the hair follicle in patients with the Birt–Hogg–Dube syndrome. Cancer Cell 2002; 2; 157–164.

- 81Schmidt LS, Nickerson ML, Warren MB et al. Germline BHD-mutation spectrum and phenotype analysis of a large cohort of families with Birt–Hogg–Dube syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005; 76; 1023–1033.

- 82Hasumi H, Baba M, Hasumi Y et al. Folliculin-interacting proteins FNIP1 and FNIP2 play critical roles in kidney tumor suppression in cooperation with FLCN. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015; 112; E1624–E1631.

- 83Baba M, Hong SB, Sharma N et al. Folliculin encoded by the BHD gene interacts with a binding protein, FNIP1, and AMPK, and is involved in AMPK and mTOR signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006; 103; 15552–15557.

- 84Jager S, Handschin C, St-Pierre J, Spiegelman BM. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) action in skeletal muscle via direct phosphorylation of PGC-1alpha. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007; 104; 12017–12022.

- 85Hasumi H, Furuya M, Tatsuno K et al. BHD-associated kidney cancer exhibits unique molecular characteristics and a wide variety of variants in chromatin remodeling genes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018; 27; 2712–2724.

- 86Klomp JA, Petillo D, Niemi NM et al. Birt–Hogg–Dube renal tumors are genetically distinct from other renal neoplasias and are associated with up-regulation of mitochondrial gene expression. BMC Med. Genet. 2010; 3; 59.

- 87Linehan WM, Srinivasan R, Schmidt LS. The genetic basis of kidney cancer: a metabolic disease. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2010; 7; 277–285.

- 88Yan M, Gingras MC, Dunlop EA et al. The tumor suppressor folliculin regulates AMPK-dependent metabolic transformation. J. Clin. Invest. 2014; 124; 2640–2650.

- 89Hasumi H, Baba M, Hasumi Y et al. Regulation of mitochondrial oxidative metabolism by tumor suppressor FLCN. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2012; 104; 1750–1764.

- 90Napolitano G, Di Malta C, Esposito A et al. A substrate-specific mTORC1 pathway underlies Birt–Hogg–Dube syndrome. Nature 2020; 585; 597–602.

- 91Furuya M, Yao M, Tanaka R et al. Genetic, epidemiologic and clinicopathologic studies of Japanese Asian patients with Birt–Hogg–Dube syndrome. Clin. Genet. 2016; 90; 403–412.

- 92Pavlovich CP, Walther MM, Eyler RA et al. Renal tumors in the Birt–Hogg–Dube syndrome. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2002; 26; 1542–1552.

- 93Trpkov K, Hes O, Williamson SR et al. New developments in existing WHO entities and evolving molecular concepts: the genitourinary pathology society (GUPS) update on renal neoplasia. Mod. Pathol. 2021; 34; 1392–1424.

- 94Tickoo SK, Reuter VE, Amin MB et al. Renal oncocytosis: a morphologic study of fourteen cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1999; 23; 1094–1101.

- 95Benusiglio PR, Giraud S, Deveaux S et al. Renal cell tumour characteristics in patients with the Birt–Hogg–Dube cancer susceptibility syndrome: a retrospective, multicentre study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2014; 9; 163.

- 96Crane JS, Rutt V, Oakley AM. Birt Hogg Dube Syndrome. StatPearls [internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing, 2022.

- 97Schmidt LS, Linehan WM. Molecular genetics and clinical features of Birt–Hogg–Dube syndrome. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2015; 12; 558–569.

- 98Rutter J, Winge DR, Schiffman JD. Succinate dehydrogenase – assembly, regulation and role in human disease. Mitochondrion 2010; 10; 393–401.

- 99Yankovskaya V, Horsefield R, Tornroth S et al. Architecture of succinate dehydrogenase and reactive oxygen species generation. Science 2003; 299; 700–704.

- 100Zhao Y, Feng F, Guo QH, Wang YP, Zhao R. Role of succinate dehydrogenase deficiency and oncometabolites in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. World J. Gastroenterol. 2020; 26; 5074–5089.

- 101Letouze E, Martinelli C, Loriot C et al. SDH mutations establish a hypermethylator phenotype in paraganglioma. Cancer Cell 2013; 23; 739–752.

- 102Selak MA, Armour SM, MacKenzie ED et al. Succinate links TCA cycle dysfunction to oncogenesis by inhibiting HIF-alpha prolyl hydroxylase. Cancer Cell 2005; 7; 77–85.

- 103Baysal BE. Mitochondrial complex II and genomic imprinting in inheritance of paraganglioma tumors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013; 1827; 573–577.

- 104Ricketts C, Woodward ER, Killick P et al. Germline SDHB mutations and familial renal cell carcinoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2008; 100; 1260–1262.

- 105Williamson SR, Eble JN, Amin MB et al. Succinate dehydrogenase-deficient renal cell carcinoma: detailed characterization of 11 tumors defining a unique subtype of renal cell carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 2015; 28; 80–94.

- 106Housley SL, Lindsay RS, Young B et al. Renal carcinoma with giant mitochondria associated with germ-line mutation and somatic loss of the succinate dehydrogenase B gene. Histopathology 2010; 56; 405–408.

- 107McEvoy CR, Koe L, Choong DY et al. SDH-deficient renal cell carcinoma associated with biallelic mutation in succinate dehydrogenase a: comprehensive genetic profiling and its relation to therapy response. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2018; 2; 9.

- 108Fuchs TL, Maclean F, Turchini J et al. Expanding the clinicopathological spectrum of succinate dehydrogenase-deficient renal cell carcinoma with a focus on variant morphologies: a study of 62 new tumors in 59 patients. Mod. Pathol. 2021. PMID: 34949766. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-021-00998-1.

- 109Gill AJ, Hes O, Papathomas T et al. Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH)-deficient renal carcinoma: a morphologically distinct entity: a clinicopathologic series of 36 tumors from 27 patients. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2014; 38; 1588–1602.

- 110Cohen AJ, Li FP, Berg S et al. Hereditary renal-cell carcinoma associated with a chromosomal translocation. N. Engl. J. Med. 1979; 301; 592–595.

- 111Woodward ER, Skytte AB, Cruger DG, Maher ER. Population-based survey of cancer risks in chromosome 3 translocation carriers. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2010; 49; 52–58.

- 112Smith PS, Whitworth J, West H et al. Characterization of renal cell carcinoma-associated constitutional chromosome abnormalities by genome sequencing. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2020; 59; 333–347.

- 113Eleveld MJ, Bodmer D, Merkx G et al. Molecular analysis of a familial case of renal cell cancer and a t(3;6)(q12;q15). Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2001; 31; 23–32.

- 114Druck T, Podolski J, Byrski T et al. The DIRC1 gene at chromosome 2q33 spans a familial RCC-associated t(2;3)(q33;q21) chromosome translocation. J. Hum. Genet. 2001; 46; 583–589.

- 115Bodmer D, Eleveld M, Kater-Baats E et al. Disruption of a novel MFS transporter gene, DIRC2, by a familial renal cell carcinoma-associated t(2;3)(q35;q21). Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002; 11; 641–649.

- 116Chen J, Lui WO, Vos MD et al. The t(1;3) breakpoint-spanning genes LSAMP and NORE1 are involved in clear cell renal cell carcinomas. Cancer Cell 2003; 4; 405–413.

- 117Melendez B, Rodriguez-Perales S, Martinez-Delgado B et al. Molecular study of a new family with hereditary renal cell carcinoma and a translocation t(3;8)(p13;q24.1). Hum. Genet. 2003; 112; 178–185.

- 118Bonne A, Vreede L, Kuiper RP et al. Mapping of constitutional translocation breakpoints in renal cell cancer patients: identification of KCNIP4 as a candidate gene. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 2007; 179; 11–18.

- 119Poland KS, Azim M, Folsom M et al. A constitutional balanced t(3;8)(p14;q24.1) translocation results in disruption of the TRC8 gene and predisposition to clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2007; 46; 805–812.

- 120Foster RE, Abdulrahman M, Morris MR et al. Characterization of a 3;6 translocation associated with renal cell carcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2007; 46; 311–317.

- 121Kuiper RP, Vreede L, Venkatachalam R et al. The tumor suppressor gene FBXW7 is disrupted by a constitutional t(3;4)(q21;q31) in a patient with renal cell cancer. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 2009; 195; 105–111.

- 122Yusenko MV, Nagy A, Kovacs G. Molecular analysis of germline t(3;6) and t(3;12) associated with conventional renal cell carcinomas indicates their rate-limiting role and supports the three-hit model of carcinogenesis. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 2010; 201; 15–23.

- 123McKay L, Frydenberg M, Lipton L, Norris F, Winship I. Case report: renal cell carcinoma segregating with a t(2;3)(q37.3;q13.2) chromosomal translocation in an Ashkenazi Jewish family. Familial Cancer 2011; 10; 349–353.

- 124Doyen J, Carpentier X, Haudebourg J et al. Renal cell carcinoma and a constitutional t(11;22)(q23;q11.2): case report and review of the potential link between the constitutional t(11;22) and cancer. Cancer Genet. 2012; 205; 603–607.

- 125Wake NC, Ricketts CJ, Morris MR et al. UBE2QL1 is disrupted by a constitutional translocation associated with renal tumor predisposition and is a novel candidate renal tumor suppressor gene. Hum. Mutat. 2013; 34; 1650–1661.

- 126Louie BH, Kurzrock R. BAP1: not just a BRCA1-associated protein. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2020; 90; 102091.

- 127Jin S, Wu J, Zhu Y et al. Comprehensive analysis of BAP1 somatic mutation in clear cell renal cell carcinoma to explore potential mechanisms in silico. J. Cancer 2018; 9; 4108–4116.

- 128Gallan AJ, Parilla M, Segal J, Ritterhouse L, Antic T. BAP1-mutated clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2021; 155; 718–728.

- 129Walpole S, Pritchard AL, Cebulla CM et al. Comprehensive study of the clinical phenotype of germline BAP1 variant-carrying families worldwide. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018; 110; 1328–1341.

- 130Carlo MI, Mukherjee S, Mandelker D et al. Prevalence of germline mutations in cancer susceptibility genes in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2018; 4; 1228–1235.

- 131Lynch ED, Ostermeyer EA, Lee MK et al. Inherited mutations in PTEN that are associated with breast cancer, cowden disease, and juvenile polyposis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997; 61; 1254–1260.

- 132Sansal I, Sellers WR. The biology and clinical relevance of the PTEN tumor suppressor pathway. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004; 22; 2954–2963.

- 133Molinari F, Frattini M. Functions and regulation of the PTEN gene in colorectal cancer. Front. Oncol. 2013; 3; 326.

- 134Marsh DJ, Coulon V, Lunetta KL et al. Mutation spectrum and genotype–phenotype analyses in Cowden disease and Bannayan–Zonana syndrome, two hamartoma syndromes with germline PTEN mutation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998; 7; 507–515.

- 135Mester JL, Zhou M, Prescott N, Eng C. Papillary renal cell carcinoma is associated with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome. Urology 2012; 79(1187); e1181–e1187.

- 136Shuch B, Ricketts CJ, Vocke CD et al. Germline PTEN mutation Cowden syndrome: an underappreciated form of hereditary kidney cancer. J. Urol. 2013; 190; 1990–1998.