Identification and description of controlled clinical trials in Spanish language dental journals

Abstract

Background

To identify controlled clinical trials (CCTs) published in Spanish and in Latin American dental journals, and provide access to this body of evidence in a single source.

Methods

Handsearching, following Cochrane Collaboration guidelines, of CCTs published in Spanish dental journals from Spain and Latin America. For each eligible trial, we collected the dental specialty, the interventions evaluated, whether and how randomisation was achieved, and the corresponding bibliographic reference.

Results

We handsearched 107 journals published in Spain and Latin America in Spanish. Over 17 051 articles, 244 (1.43%) were CCTs. These studies focused mainly on periodontics (70, 29.0%) and oral and maxillofacial surgery (66, 27.0%), assessing mostly pharmacological interventions (112, 46.0%). One hundred fifty-three studies (62.7%) used a random allocation of participants to study arms.

Conclusions

A significant number of dental journals published in Spain and Latin America in Spanish language present original research relevant to inform clinical practice. These journals are not indexed in the major electronic databases.

Practical Implications

References to the identified CCTs are now available in CENTRAL, the Cochrane Collaboration repository for these studies. We call for adherence to the CONSORT statement in dentistry to improve reporting of CCTs in journals published in Spanish language.

Key Messages

- The references retrieved in this study have been sent to CENTRAL, the Cochrane Collaboration registry of controlled clinical trials (CCTs), for their potential inclusion in systematic reviews.

- Dental researchers should adhere to the CONSORT statement to ensure good practice on design and reporting of CCTs.

- Most Spanish language journals, which contribute to the scientific evidence base in the field of Dentistry, are not indexed in the major bibliographic databases.

- Handsearching is therefore needed to retrieve CCTs published in Spanish language dental journals.

Introduction

Controlled clinical trials (CCTs) are considered the best approach to assess the effects, benefits and harms of a therapeutic intervention, drug, device or technique in human beings (Bonfill et al., 2013; Cañedo Andalia, Arencibia, Perezleo Solorzano, Conill González & Araújo Ruiz, 2004; Dickersin, Scherer & Lefebvre, 1994; Manríquez, Valdivia, Rada & Letelier, 2005). CCTs are also the foundation of systematic reviews and other evidence synthesis documents (Garcia-Alamino et al., 2006). However, identifying all CCTs on a specific intervention is complex (Hopewell, Clarke, Lefebvre & Scherer, 2007) due to issues associated with bias in the reporting of CCTs.

Reporting bias arises from a tendency of investigators to report research results depending on the strength, direction or statistical significance of results (McGauran et al., 2010; Meerpohl et al., 2015). Reporting bias takes several forms, including delays in the reporting of research results (time-lag bias), reporting in journals depending on its impact factor or level of indexation on bibliographic databases (location bias), reporting in English as opposed to other languages (language bias), differential reporting of outcomes that had been pre-defined in study protocols (selective outcome reporting), or reluctance to disseminate research via scientific articles or other methods (dissemination bias), all in function of the nature of the obtained results (McGauran et al., 2010).

Reporting bias has serious ethical and economical implications. It undermines the contribution of participants in CCTs, who often invest time and money without the assurance of benefit from an intervention (or no intervention). They accept the possibility of potential adverse events as well as of uncertainty derived from blinding to treatment interventions and other methodological practices (Jones et al., 2013; McGauran et al., 2010). Reporting bias also results often in redundant work, since unpublished research may be revisited by other investigators, with the consequent waste in economic and human resources (Moher et al., 2016) Not surprisingly, reporting bias has been targeted as one the main challenges of the evidence-based medicine movement for the upcoming years (Djulbegovic & Guyatt, 2017).

The Cochrane Handbook provides several approaches for addressing the possibility of reporting bias during the development of systemic reviews. The most commonly used is the need of developing properly designed search strategies that are applied to different databases and repositories (McGauran et al., 2010). However, using exclusively electronic databases (e.g. MEDLINE, EMBASE) has shown to be suboptimal (Iberoamericano, 2012) due to several reasons. First, the term CCT was not indexed as such until 1990 and incorporated into MEDLINE and EMBASE in 1991 and 1994, respectively. Therefore, CCTs prior to this date were classified using broader categories. Second, data suggest that the descriptors available in databases have been used inconsistently by those responsible for their codification and classification (Dickersin et al., 1994). Third, in some occasions, authors do not report their research methods clearly enough, which hinders the CCTs indexing process (Koletsi, Pandis, Polychronopoulou & Eliades, 2012).

Regarding literature in Spanish, even though there are several databases, directories and registries that allow searching for journals in Spanish language (e.g. LILACS, SCIELO, PERIODICA, IMBIOMED, LATINDEX and PUBMED), none contain all existing journals. Moreover, some databases can provide outdated and/or incomplete information (Armstrong, Jackson, Doyle & Waters, 2005; Betrán, Say, Gülmezoglu, Allen & Hampson, 2005; Hopewell, Clarke, Lusher, Lefebvre & Westby, 2002), including inactive journals that are marked as active, with obsolete contact information, or inaccurate data about the publishers. This supports the notion that it is necessary to broaden searches for dental journals to libraries, catalogues, publishers and specialised registries. Last but not least, electronic searches do not retrieve studies from journals that are not regularly indexed in the classic databases. The large increase in the number of studies published in Spanish language during the last decade makes it imperative to overcome this problem (Reveiz et al., 2006).

One of the strategies proposed to overcome the shortcomings of electronic searches is the implementation of a rigorous and thorough handsearching approach (Dickersin et al., 1994; García-Alamino, Parera, Ollé & Bonfill, 2007; Martí, Bonfill, Urrutia, Lacalle & Bravo, 1999). The superiority of handsearching over electronic searching has been reported in studies that tried to identify the maximum possible number of CCTs on Anesthesiology (García-Alamino et al., 2007; Suarez-Almazor, Belseck, Homik, Dorgan & Ramos-Remus, 2000), General and Internal Medicine (Martí et al., 1999), Patient Safety (Barajas-Nava, Calvache, López-Alcalde, Sola & Bonfill, 2013), among others.

The main objective of this study was to conduct a comprehensive search to identify CCTs published in Spanish language dental journals from Spain and Latin America. We also aimed to provide researchers with access to this body of evidence in a single source, namely CENTRAL, the Cochrane Collaboration repository of CCTs, to facilitate the inclusion of these studies in future systematic reviews.

Methods

We manually and retrospectively identified CCTs published up to 2014 in dental journals published in Spanish language in Spain and the 18 Spanish-speaking countries in Latin America: Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela.

Handsearching was conducted retrospectively, backwards from the last year of publication. If CCTs were not found in any of six consecutive years, the handsearch for the journal in question was stopped.

Identification of dental journals

The overarching definition of Dentistry we used was ‘the medical discipline responsible for everything concerning the evaluation, diagnosis, prevention and/or treatment (nonsurgical, surgical or related procedures) of diseases, disorders and/or conditions of the oral cavity, maxillofacial area and/or the adjacent and associated structures and their impact on the human body; provided by a dentist, within the scope of his/her education, training and experience, in accordance with the ethics of the profession and applicable law ‘(ADA 2017).

We initially identified all journals that would be subjected to handsearching using methodology that has been published elsewhere (Bonfill et al., 2015). In brief, to identify potentially eligible journals, we searched the catalogue of indexed publications in MEDLINE (accessed via PubMed) screening by country and combining the key terms [Dentistry] AND [Country of Publication]. Subsequently, we consulted the ‘Centro Latinoamericano y del Caribe de Información en Ciencias de la Salud- BIREME’, to have access to Scielo (www.scielo.org) and LILACS for dental journals classified under the Health Sciences category, as well as Latindex, an online repository of journals curated by the National University of Mexico (Universidad Nacional de México). We searched Google, Google Scholar and regional databases such as C17, SeCiMed, the Spanish Medical Index or IME (Instituto Médico Español), Compludoc, Cisne catalogue (Spain), Imbiomed (Mexico), Colciencias (Colombia) and Conicyt (Chile) for publications of dental and scientific associations and dental schools of every country in Latin America and Spain. Lastly, we polled members of the Iberoamerican Cochrane Network for journals that could have been missed.

To be eligible, a journal had to publish original research in Dentistry, regardless of whether it was active at the time of the search.

Identification of CCTs

We identified CCTs through systematic handsearching of all eligible journals. Each journal was carefully examined, including original articles, letters to the editor and reference sections, following the recommended steps for handsearching developed by the Cochrane Collaboration (Iberoamericano, 2012):

- Read the table of contents,

- Identify keywords in the title of the article (e.g. randomised, blind, random),

- Read the abstract of potentially eligible articles and

- Read the ‘Material and Methods’ section of potentially eligible articles.

Researchers from the Universidad de Chile Faculty of Dentistry (Santiago, Chile), the Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Madrid, Spain) and the Universidad de Antioquia (Medellín, Colombia) handsearched the articles. The search started with the latest issue available of each journal retrospectively until the year of inception (first issue). We stopped handsearching a journal after six consecutive years of unsuccessful identification of any CCT. The screening was conducted using a standardised form; we collected bibliographic information about the journal the databases where it was indexed, whether it had an impact factor, whether it required adherence to CONSORT for publication, and the publisher or responsible institution. We also recorded the total number of articles reviewed and CCTs identified.

To be considered a CCT, a study had to comply with all of the following criteria, proposed by the Cochrane Collaboration:

- Focus on comparative effectiveness of treatment interventions in humans,

- Be prospective: interventions had to be planned before the study was conducted,

- Compare two or more treatments or interventions, one of which could be a control group with an active comparator, no treatment, or placebo,

- Assess interventions that may have been pharmacological, diagnostic, rehabilitative, organisational, surgical or educational and

- Adopt a method to allocate individuals, groups (hospitals or communities), organs (e.g. eyes) or human body parts (e.g. teeth) to one or more intervention and/or control group. Studies that met these criteria were further classified into

- Randomised clinical trial (RCT): the author(s) stated that treatment allocation of eligible subjects was random (or used equivalent words, e.g. ‘by chance’) or

- Controlled clinical trial: the authors did not specify that allocation to treatments had been random (or use of an equivalent term), but describes or refers to a ‘quasi-random’ method.

All the handsearching process was conducted in duplicate (ID-MG, LN-YA, JS-SZ). Two authors (JV and CM) verified eligibility of every potential CCT identified. Discrepancies were solved by consensus or by consulting a third author (SZ).

For each identified CCT, we determined the dental subspecialty (e.g. periodontics, oral and maxillofacial surgery, oral rehabilitation) in accordance with the corresponding research topic, the interventions evaluated, the random sequence generation method (if any) and the corresponding bibliographic reference.

Data extraction

To ensure a trustworthy data extraction process, a database was set up where all potential CCTs were registered, and every journal was tracked. Also, a data collection logbook was created including all variables of interest, which are detailed in Table 1. All identified CCTs were entered in BADERI (Iberoamerican journals and trials database by its initials in Spanish), which allows immediate submission via ProCite files of all identified CCTs to CENTRAL (Pardo-Hernandez et al., 2017)

|

Statistical analysis

We performed a descriptive analysis using Excel 2013 (Microsoft®).

Results

Identification of the journals

A total of 107 dental journals from Spain and Latin American countries were identified (Table 2). No journals were identified from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay or the Dominican Republic. For over 70% of the journals identified, the publisher was an academic institution (e.g. university) and three (2.8%) had no ISSN. Over half (51.4%) of the journals identified were indexed in more than one bibliographic database, although six were indexed in MEDLINE (5.6%) and one in EMBASE (0.9%). One journal (0.9%) in Spain reported an impact factor in 2014 (Medicina Oral Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal, impact factor: 1.171). None of the journals had specific policies requiring adherence to CONSORT as a requirement for publication.

| Country | No. of journals | No. of articles reviewed | No. of CCTs | (Number of CCTs/number of articles reviewed) *100 | Proportion of total CCTs identified (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain | 37 | 7605 | 104 | 1.4% | 42.6 |

| Chile | 16 | 1933 | 53 | 2.7% | 21.7 |

| Argentina | 15 | 1260 | 6 | 0.5% | 2.5 |

| Mexico | 11 | 1458 | 16 | 1.1% | 6.6 |

| Colombia | 10 | 1503 | 29 | 1.9% | 11.9 |

| Venezuela | 7 | 1760 | 20 | 1.1% | 8.2 |

| Peru | 4 | 736 | 16 | 2.2% | 6.5 |

| Costa Rica | 2 | 191 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Uruguay | 2 | 135 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bolivia | 1 | 130 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cuba | 1 | 307 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ecuador | 1 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 107 | 17 051 | 244 | 1.4% | 100.0 |

- CCT, controlled clinical trial.

Identification of CCTs

A total of 17 051 articles were reviewed in eligible journals (Table 2), 244 of which were CCTs (1.43%). Of these, 104 were published in journals from Spain (42.6%), 53 from Chile (21.7%), 29 from Colombia (11.9%), 20 from Venezuela (8.2%), 16 from Mexico (6.5%), 16 from Peru (6.5%) and six from Argentina (2.5%) (Table 2). No CCTs were found in journals from Bolivia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador or Uruguay.

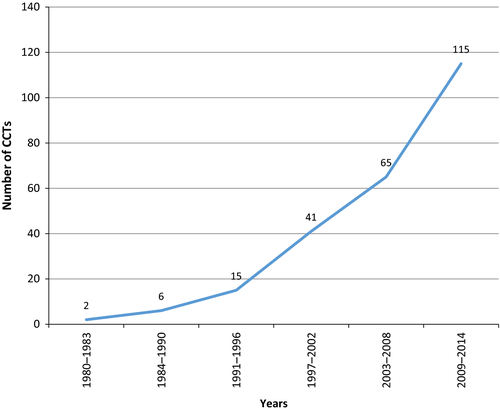

Chile (2.7%) and Peru (2.2%) had the highest number of CCTs per number of articles reviewed (1.4%) (Table 2). When assessing the number of CCTs published over time, we found a sustained increment, with 115 CCTs published in the 2009–2014 period alone. (Figure 1).

Identified CCTs focused on ten dental specialties, with periodontics (70, 29.0%) and oral and maxillofacial surgery (66, 27.0%) prevailing over others (Table 3). Most CCTs examined interventions related to pharmacological interventions (112, 46.0%), restorative techniques (16, 7.0%), prosthetic rehabilitation (15, 6.0%) or educational interventions (13, 5.0%) (Table 4). Over 153 studies (62.7%) used random treatment allocation, 51 (20.9%) were classified as quasi-randomised, and 40 (16.4%) did not specify the method of allocation of patients in the compared groups.

| Specialty | Number of CCTs identified | Proportion of total CCTs (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Periodontics | 70 | 29 |

| Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery | 66 | 27 |

| Oral Rehabilitation | 25 | 10 |

| Restorative Dentistry | 23 | 9 |

| Pediatric Dentistry | 13 | 5 |

| Orthodontics | 12 | 5 |

| Oral Pathology | 10 | 4 |

| Implant Dentistry | 8 | 3 |

| Occlusion and Temporomandibular Disorders | 8 | 3 |

| Not classifiable | 6 | 2 |

| Endodontics | 3 | 1 |

| Total | 244 | 100 |

- CCT, controlled clinical trial.

| Intervention | Number of CCTs identified | Proportion of total CCTs (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmacological Interventions | 112 | 46 |

| Restorative approaches | 16 | 7 |

| Prosthetic rehabilitation (removable partial dentures, overdentures, etc.) | 15 | 6 |

| Educational intervention | 13 | 5 |

| Periodontal approach | 12 | 5 |

| Surgical approach | 10 | 4 |

| Plaque control techniques | 8 | 3 |

| Bone regeneration techniques | 7 | 3 |

| Dental materials (dental porcelain, dental cements, bolt, etc.) | 7 | 3 |

| Oral hygiene materials (toothbrushes, dental floss, etc.) | 7 | 3 |

| Types of interocclusal appliances | 6 | 2 |

| Types of dental implants | 5 | 2 |

| Laser treatment | 4 | 2 |

| Hygiene techniques | 4 | 2 |

| Other interventions | 18 | 7 |

| Total | 244 | 100 |

- CCT, controlled clinical trial.

Discussion

In this study, we identified 107 dental journals publishing original clinical in Spanish language. We found that less than a third of these journals are indexed in more than one bibliographic database. Moreover, the low proportion of journals indexed in MEDLINE (5.6%) and EMBASE (0.9%) is alarming given the relevance and recognition associated with these databases by the international scientific community (Suarez-Almazor et al., 2000). In addition, only one publication (0.9%) had an impact factor in 2014 (1.171). It is possible that this situation discourages many Spanish-speaking authors from publishing in local journals. Given the fact that the impact of their publications has a direct effect on the evaluation of their research and professional achievements, they may be motivated to publish their work elsewhere, in international, English language journals that are indexed or have an impact factor (Armstrong et al., 2005; Crumley, Wiebe, Cramer, Klassen & Hartling, 2005; Hopewell et al., 2002).

The term ‘randomised or controlled clinical trial’ has become more common in the titles of articles published in dental journals over time. However, a large number of these articles do not meet the requirements to be classified as such. A recent study (Koletsi et al., 2012), published in 2012, observed articles published in dental journals with highest impact factor, representing five dental specialties and assessed the consistency between the title reporting the study as a randomised clinical trial and whether they were indeed RCTs (19). Between 1979 and 2011, a total of 222 trials were detected, of which 88 (39.6%) were considered RCTs, 107 (48.2%) were deemed ‘not clear’, and 27 (12.2%) were not considered RCTs (Koletsi et al., 2012).

Our study does not have this limitation as we not only screened the title and abstract of the included reports but also verified in the ‘Materials and Methods’ sections that each eligible study was truly a CCT. Only 27 articles contained the term ‘clinical trial’ in the title, which could indicate that both authors and dental journal editors publishing in Spanish lack awareness of the CONSORT statement (Schulz, Altman & Moher, 2010), at least since it was published and accepted by the scientific community. Similar trends have been reported by other authors assessing the quality of reporting in Orthodontics randomised controlled trials (Fleming, Buckley, Seehra, Polychronopoulou & Pandis, 2012). Our search also showed an increase in the number of published CCTs starting in the nineties, which is in line with the findings of Martí et al. (Martí et al., 1999) in General and Internal Medicine journals, and of other similar studies (Chung & Lee, 2013; Hopewell et al., 2002; Manríquez et al., 2005).

In our opinion, the low number of published CCTs reflects the insufficient development of this important line of clinical research in dental journals published in Spanish. This phenomenon could also be explained by a preference of Spanish and Latin American authors to publish in foreign journals with a greater impact factor.

Despite these shortcomings, we believe it is important to increase visibility of the CCTs published in local and Spanish language journals to control the effects of reporting bias, specifically regarding language and location bias, during the development of systematic reviews and other documents of synthesis. The Cochrane Collaboration, through the Methods Expectations for Cochrane Intervention Reviews (MECIR Standards) (Higgins, Lasserson, Chandler, Tovey & Churchill, 2016), recommends searching for CCTs in regional databases, such as LILACS, as well as handsearching the reference sections of eligible studies and other sources, to complement the search results of electronic strategies. Through the work we have conducted here, especially by submitting the identified CCTs to CENTRAL, we hope to decrease the burden inherent to these tasks. In addition, the process of identifying CCTs in eligible dental journals from Spain and Latin America is ongoing. The Iberoamerican Cochrane Centre coordinates an effort for regularly contacting editors of eligible journals that were found to publish CCTs requesting new CCTs published after the search period of this study (Bonfill et al., 2017; Pardo-Hernandez et al., 2017). Newly identified CCTs will also be submitted to CENTRAL.

The main strengths of our study are the comprehensive handsearching approach we took for identifying eligible CCTs. The handsearching process was conducted in duplicate, which minimises the risk of including ineligible CCTs or leaving out real CCTs. We looked at a high volume of journals, all of which, at least in theory, publish original research, and were able to review over 17 000 references.

Our work also has some limitations. We focused only on dental journals, which may have left out CCTs on this discipline published in General Medicine, Surgery or other types of Spanish language journals. In addition, as mentioned throughout the article, we did not review journals in English language or from countries outside Spain and Latin America. Therefore, our work does not include CCTs, presumably of higher quality, that Spanish and Latin American authors may have published in those journals.

Future research projects should attempt to identify studies by Spanish and Latin American authors published in international, English language journals. Additionally, it would be useful to assess in depth the risk of bias in the CCTs identified in this study. This would further improve their usefulness for inclusion in systematic reviews and other evidence summaries. Lastly, the handsearching process should and will be conducted prospectively from the point where it was stopped in this article. New CCTs identified in handsearched dental journals will be uploaded into BADERI and submitted to Central regularly.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that retrieves and describes CCTs published in dental journals in Spanish language. The methodological measures we took to complete this study, including the collaborative approach among researchers in different countries to identify CCTs that are not retrievable using electronic searches, as well as the rigour with which the handsearching of eligible journals was completed, may be informative to the readership of Health Information and Libraries Journal for designing future research projects. Likewise, the identification of these studies, as well as the list of journals and websites (Bonfill et al., 2015), brings to the research and clinical communities the opportunity to access additional evidence that may have been ignored by systematic reviewers in the past. Moreover, our work helps to increase the visibility of CCTs published in dental journals that are not indexed in any database. References to all CCTs identified are available and accessible via CENTRAL, the Cochrane Collaboration CCT register, for potential inclusion in systematic reviews and other evidence synthesis documents. The inclusion of these articles in ongoing and future systematic reviews may increase the strength of the conclusions or change the direction of relevant findings.

Conclusions

There are a considerable number of dental journals from Spain and Latin America publishing CCTs. However, they are not indexed in the most used electronic databases, which limits their visibility for potential inclusion in systematic reviews and meta-analysis. In addition, the ratio of CCTs relative to all the studies published in these journals is almost negligible (1.4%). We therefore believe it is necessary to promote research and the development of CCTs in this field in Spain and Latin America. Finally, to ensure proper reporting of CCTs, journals should require adherence to CONSORT as requirement for publication.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Andrea Cervera Alepuz for her help translating the final version of the manuscript from Spanish into English, and Alonso Carrasco Labra for his opinion and to correct the style. The authors would like to thank Alonso Carrasco Labra for his input for this study, as well as Andrea Cervera Alepuz for correcting the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interests

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Funding

There was no funding available for this study.

Ethics approval

No ethical approval was required for this study.